Patient Safety and Sustainable Development Goals

Through the Lens of Health Information Management

Trixie Kemp; Kerryn Butler-Henderson; Jennifer Ayton; and Salma Arabi

Learning Outcomes

- Explain the HIM professionals’ crucial role in patient safety through the functions they perform.

- Analyse the impact of the HIM professionals’ role in supporting a health organisation to achieve the Sustainable Development Goals.

- Evaluate health information and data-related solutions to address the challenges impacting patient care and patient safety.

Introduction

This chapter provides a comprehensive overview of patient safety and quality in healthcare, including its origins, how it is monitored and measured, and developments within Australia. References are also made to global work in patient safety. Examples of quality and safety initiatives are discussed through the lens of health information management (HIM) and how HIM professionals contribute to patient safety within the health system. The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (United Nations, 2024c) (SDG) #3 Good Health and Well-being and #16 Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions (United Nations, 2024c) are used to explore how quality health information improves population-level health outcomes.

HIM professionals are integral to maintaining robust health systems. They possess a distinctive blend of skills and knowledge that uniquely positions them at the intersection of health records and patient safety (Kemp et al., 2021a). Their involvement in managing health records and ensuring data quality, as well as their role in reporting and funding, demonstrates the direct application of their formal education for patient safety-related functions. HIM professionals’ ability to interpret data at various levels and understand the healthcare system further underscores their relevance in addressing patient safety (Kemp, et al., 2021a).

Three examples are provided to explore patient safety through the lens of HIM, providing deeper discussion and analysis of the relationship. Hospital-acquired complications are explored to show how HIM professionals are involved with identification and data monitoring, reporting, and trending. Electronic health records (EHRs) are then examined for data security and safety features and to demonstrate how HIM professionals contribute to system governance. Lastly, HIM professionals’ roles in clinical governance are examined, including auditing and accreditation processes, education and training, and documentation.

The chapter concludes with insights from Australian HIM and patient safety leaders on how HIM professionals contribute to patient safety and the relationship to SDG #3 and SDG #16. These insights are taken from current research underway by the lead author on the themes of data, documentation, education, and records management.

Background

In simple terms, patient safety is the prevention of errors and adverse events associated with healthcare settings. The World Health Organization (WHO, 2024a) states, “Patient safety is a framework of organised activities that creates cultures, processes, procedures, behaviours, technologies and environments in health care that consistently and sustainably lower risks, reduce the occurrence of avoidable harm, make error less likely and reduce its impact when it does occur”. Patient safety is not new; it has been practised since Hippocrates’ time with the “do no harm” principle (Kemp, 2021b). Patient safety has become a recognised field within healthcare over the last 20 years with the release of The Quality of Australian Health Care Study (1995) (Wilson et al., 1995), which discussed the prevalence of adverse events for 16.6% of admissions in Australian hospitals, and To Err is Human: Building a Safer Healthcare System report (Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality of Health Care in America, 2000), which revealed adverse events as the eighth leading cause of death. The WHO stated that patient safety is a global priority (WHO, 2019) and adopted resolution WHA72.6 on “Global action on patient safety” at the 72nd World Health Assembly. The Global Patient Safety Action Plan 2021–2030 (WHO, 2019) outlines seven strategic objectives, each accompanied by five corresponding strategies. The vision of this plan is “A world in which no one is harmed in health care, and every patient receives safe and respectful care, every time, everywhere”.

In 2006, the Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (ACSQHC) was established to coordinate national quality and safety improvement by providing information and resources and developing National Safety and Quality Healthcare Service (NSQHS) Standards, clinical care standards, and an accreditation scheme (ACSQHC, 2021). Accreditation is a formal process that evaluates and certifies that a healthcare organisation meets established standards (ACSQHC, 2021). These standards are considered optimal and achievable, promoting continuous improvement (WHO, 2021). The Commission examines Australia’s health system by monitoring sentinel events, mortality indicators, hospital-acquired complications, and hospital-based indicators (ACSQHC, 2019). Multiple data sources are used to monitor and report on the state of patient safety in the Australian healthcare system. The Commission also approves accrediting agencies such as the Australian Council on Health Care Standards to assess health services against the NSQHS Standards (ACSQHC, 2025). Similar programs also run in other countries, predominantly high-income countries, and globally, with some examples (not all) shown in Figure 1. The WHO has promoted accreditation in low-middle income countries to address healthcare quality (Nicklin et al., 2021). Low-middle income countries have adapted and implemented global accreditation programs, originally from high-income countries, to suit their local needs (Mansour et al., 2020). The sustainability of accreditation programs remains a challenge for low-middle income countries due to resourcing, which is dependent on a country’s financial and political climate (Mansour et al., 2021).

| Number | Accreditation Body |

|---|---|

| 1 | Australian Council on Health Care Standards (2024) |

| 2 | National Committee for Quality Assurance (United States Government, 2005) |

| 3 | Accreditation Canada (2024) |

| 4 | Council for Health Service Accreditation of Southern Africa (2022) |

| 5 | Saudi Central Board for Accreditation of Healthcare Institutions (Saudi Central Board for Accreditation of Healthcare Institutions, 2024) |

| 6 | Care Quality Commission (2024), United Kingdom Accreditation Service (2024) |

| 7 | Health Information and Quality Authority (2024) |

| 8 | Haute Autorité de Santé (2024) |

| 9 | Accreditation Board for Hospitals and Healthcare Providers (National Accreditation Board for Hospitals and Healthcare Providers, 2024) |

| 10 | Taiwan Joint Commission on Hospital Accreditation (Joint Commission of Taiwan, 2023) |

| 11 | International Society for Quality in Health Care (2020) – Global |

| 12 | Joint Commission International (Joint Commission International, 2024a) – Global |

While governance frameworks for monitoring patient safety differ across countries, the common element is the need for reliable information to understand the patient safety landscape in all health facilities. Six international patient safety goals have been developed to monitor the most problematic areas of patient safety:

- Identify the patient correctly

- Improve effective communication

- Improve the safety of high-alert medications

- Ensure safe surgery

- Reduce the risk of healthcare-associated infections

- Reduce the risk of patient harm resulting from falls (Joint Commission International, 2024b).

The WHO (2019a) has linked patient safety to the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG), namely SDG-3, “Ensure healthy lives and promote health and well-being for all ages”. The SDGs (Figure 2) were adopted by all countries in the United Nations in 2015 as part of the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, which includes 17 goals and 169 targets (United Nations, 2024c). Progress in one goal impacts the attainment of other goals. For example, SDG-2 (WHO, 2024c) aims to achieve zero hunger and enhance nutrition, directly improving health and well-being (SDG-3). Additionally, SDG-16 (WHO, 2024c) promotes just, peaceful, and inclusive societies, aligning with fundamental human rights such as privacy and access to information while ensuring individuals feel safe in their daily lives. The health and well-being of individuals are impacted by war, conflict, poverty, disease, and human rights abuses.

Activity – Drag and drop

Origin of Sustainable Development Goals

The SDGs were developed based on knowledge, experience, and work accumulated over 40 years through various programs and reports. Policymakers’ lack of focus on environmental issues was the focus at the 1972 United National Conference on the Environment, which led to the creation of the United Nations Environment Programme (Virchow Foundation, 2021). Building on this work, the Our Common Future Report (Brundtland, 1987) addressed sustainable development for the first time by considering the impact and future generation needs (Virchow Foundation, 2021). Twenty years on from United National Conference on the Environment, the Agenda 21 action plan aimed to improve lives and the environment through global partnership (Virchow Foundation, 2021). In 2000, the Millennium Goals were created as a global effort to address extreme poverty, hunger, prevent deadly diseases and provide education to children (United Nations Development Programme, 2024). Despite work in the previous decades, more was required, and the SDG were created in 2015 as a 15-year plan to address the impact on everyone (United Nations Development Programme, 2024; World Health Organization, 2024c). Like any plan, data are essential to measuring progress. For health-related actions, these data are collected through a variety of methods, for example, digital, paper, devices, and by staff and clinicians in the health system.

Examining SDG-16 (United Nations, 2024c) further, it aims to build strong and effective institutions to ensure justice and security from conflict, violence, human rights violations, and persecution. This goal progresses through 12 targets and is measured through 23 indicators (Global Goals, 2024). Everyone in society can contribute to SDG-16 by demonstrating compassion, following the law, being inclusive, and not committing violence (United Nations, 2024c). Specifically, Target 16.10 – Public access to information and protect fundamental freedoms in accordance with national legislation and international agreements (Global Goals, 2024; United Nations, 2024b), is relevant to HIM professionals, as they are the custodians of health information and therefore support access to information, while also protecting that information through privacy practices.

SDG-3 Healthy lives and well-being for all, comprises 13 targets and 28 indicators covering topics such as maternal mortality, neonatal and child mortality, infectious diseases, non-communicable diseases, substance abuse, road traffic deaths, sexual and reproductive health, universal health coverage, environmental health and tobacco control (United Nations, 2024a). The non-medical factors influencing health outcomes are social determinants of health. These are “conditions in which people are born, grow, work, live, and age, and the wider set of forces and systems shaping the conditions of daily life which include economic policies and systems, development agendas, social norms, social policies, and political systems” (WHO, 2024b). Achieving SDG-3 is related to addressing the many determinants that drive health outcomes (Keshavarz Mohammadi, 2022). Websites such as “OurWorldData” (Our World Data Team, 2023) bring together data from various sources to provide tables and visualisations on global progress. Most of these targets use metrics that require data captured in health records and through clinical coding, such as ICD-10 codes. Therefore, the HIM profession is vital in supporting health and well-being through the provision and availability of required data.

Despite advances in understanding the factors contributing to patient safety, challenges remain. Schiff and Shojania (2022) described these challenges within three themes: health system, settings of care, and staff. Some sub-themes are directly relevant to HIM. The “health system” theme includes issues with the validity of metrics that hinder meaningful improvement. The “settings of care” theme focuses on data collection but neglects the critical cycle of measurement and improvement. Additionally, it identifies multiple challenges with EHRs, a term also used interchangeably with electronic medical records (EMRs) in the Australian setting, including alert fatigue, complex decision support, difficulties in improving existing systems, clinical documentation with manual chart reviews, and closed-loop failures with tracking test results, referrals, and symptoms (Schiff and Shojania, 2022). Australian clinicians also report usability challenges, with initiatives to address sign-on issues, templates, and clinician decision support alerts identified as potential solutions (Lloyd et al., 2024). Finally, the “staff” theme addresses significant concerns such as staff shortages, lack of time and support, burnout, lack of interest, and detachment from staff and patients (Schiff and Shojania, 2022).

HIM professionals are at the intersection between health records and patient safety due to their role in managing health records, data quality, patient identification and matching, privacy and security, activity reporting, and funding (Kemp, et al., 2021b). Physicians have used health records for thousands of years to communicate information about illness, injury, and disease (Kemp, et al., 2021a). As health records evolved, they became a valuable tool for patient safety due to the information they contained (Kemp, et al., 2021a). The HIM profession is ideally placed in patient safety activities due to their knowledge and training in the healthcare system, patient anatomy, and physiology, which supports the interpretation of data at the patient, facility, organisation, state, and national levels. These data are crucial for monitoring patient safety. Continued efforts to advance the quality and safety of health services will lead to improved health and well-being of individuals (SDG-3) and stronger institutions (SDG-16). The three cases below provide deeper discussion and analysis into where the work of HIM professionals interfaces with patient safety and sustainable development goals.

Case 1 – Hospital Acquired Complications

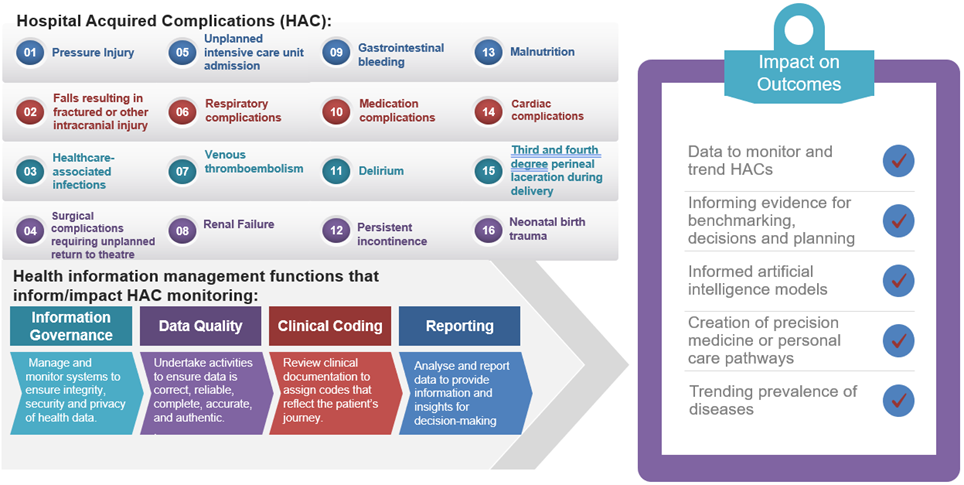

A hospital-acquired complication (HAC) is defined by the Independent Health and Aged Care Pricing Authority (IHACPA) as “a complication that occurs during a hospital stay and for which clinical risk mitigation strategies may reduce (but not necessarily eliminate) the risk of that complication occurring” (IHACPA, 2024). The ACSQHC (2018) lists 16 HACs (included in Figure 3) monitored for patient safety and quality improvement opportunities using data captured within health records and systems. The diagram shows hospital acquired complications and the health information management functions that impact monitoring such as information governance, data quality, clinical coding and reporting.

HACs have an economic impact on health services, such as longer lengths of stay (Fernando-Canavan et al., 2021). The role of the HIM professional is to identify HACs during the clinical coding process and through specific audit activities. These data are then used to track, trend, and report on the frequency and location of HACs within the health service. The accuracy of the clinical documentation directly impacts this coded data (Davis & Shepheard, 2024). For example, a study at two Victorian hospitals identified that 48.89% of urinary tract infections had been incorrectly identified as hospital-acquired due to poor-quality clinical documentation (Liu et al., 2022). As shown in Figure 3, HIM professionals undertake a variety of functions that inform or impact HAC monitoring. HIM professionals work with clinicians and quality and patient safety staff to draw conclusions and insights from the data to support targeted efforts to address the frequency of HACs and take measures to prevent them. The clinical codes assigned represent a story; for example, J18.9 with a condition onset flag of 1 is hospital-acquired pneumonia; this is HAC#3 healthcare-associated infection. If multiple patients from the same ward or hospital have this code assigned, this could indicate a system issue that needs further investigation. Undertaking an audit on clinical documentation to check that skin integrity checks are completed on admission could show whether pressure injuries (HAC#1) are hospital-acquired or occurred prior to attending the hospital. By providing oversight and governance of information, HIM professionals ensure data are available, reliable, relevant, and complete. Reliable data are essential for informed evidence-based care decisions, service planning and monitoring, and disease surveillance.

Case 2 – Electronic Health/Medical Records

Regardless of their medium, health records are used for patient care and treatment, research, disease surveillance, funding, service planning, and benchmarking (IFHIMA, 2022). With the introduction of EHRs there has been an increase in the amount of data generated and digital health interventions that support patient care (Butler-Henderson, 2017). Multiple terms are used in Australian local health areas to describe EHRs; for example, digital patient chart, single digital patient record, and most frequently, EMRs. Some EHRs include electronic patient portals, information exchange, computerised order entry, electronic prescribing and decision-support systems (Shaw et al., 2018) (see glossary for definitions of the terms EHR and EMR). As EMRs evolve, they are becoming more sophisticated in how they support clinicians in providing safe health care, such as alerts for drug interactions, medication duplications, and same tests ordered within a nominated timeframe (Sittig et al., 2018). Future potential related to AI and personalised medicine will be directly linked to EMRs (Stanfill & Marc, 2019). Further, as data systems become linked across health, social services, education and other sectors, they can create a complete picture across the social determinants of health, allowing monitoring and forecasting health outcomes and service requirements (Chen et al., 2020).

Oversight is required for EHRs to be used safely and effectively. Information governance outlines the principles, policies, and procedures for organisations to exercise stewardship of information assets, including technology (IFHIMA, 2021). The HIM professional is central to ensuring the confidentiality, data quality, accessibility, and management of the information within the EHR is properly governed through its lifecycle. Even in a fully digital health organisation, the role of the HIM professional is important for information governance, which then impacts safety (Kemp et al., 2025). For this reason, it is necessary for HIM professionals to hold formal qualifications and skills in these domains. When considering information governance with EHRs, HIM professionals are involved with managing duplicate patient identities, the privacy and security of information, data integrity and data standards, and structuring information for different uses (Kemp et al., 2021b). Without this expertise, the integrity of the central communication tool for safe patient care and source of data to inform the management and planning of health services could be compromised.

Case 3 – Clinical Governance

The ACSQHC (2021) defines clinical governance as a “set of relationships and responsibilities established by a health service organisation between its state or territory department of health, governing body, executive, workforce, patients, consumers, and other stakeholders to ensure good clinical outcomes. It ensures that the community and health service organisations can be confident that systems are in place to deliver safe and high-quality health care and continuously improve services”.

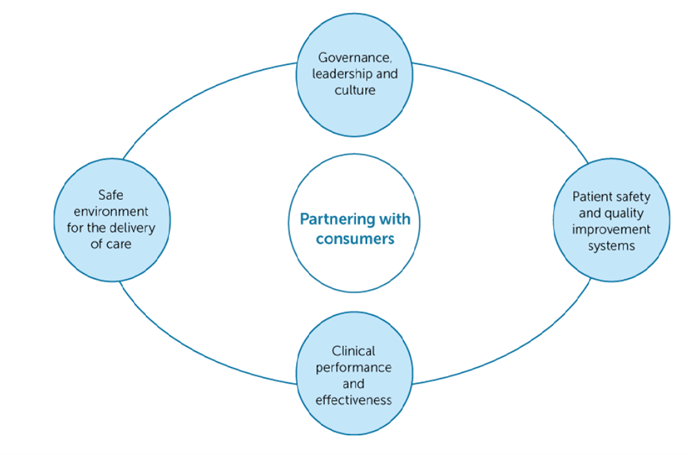

Clinical governance frameworks provide organisations with a consistent approach to addressing quality and safety in patient care as they provide a clear delineation of roles, responsibilities, and accountabilities (ACSQHC, 2017). HIM professionals are directly and indirectly involved in the five elements of the Australian National Model Clinical Governance Framework (Figure 4). By participating in education and committing to quality and patient safety, employees contribute to the organisation’s safety culture, addressing the first element of “Governance, Leadership and Culture”. As HIM professionals produce the data and information to support quality assurance, monitoring, and improvement, their work aligns with “Patient Safety and Quality Improvement Systems” (Element Two). Element Three, “Clinical Performance and Effectiveness”, is supported by providing education on good quality clinical documentation and other health information-related topics. By reporting on trends identified with the data on HACs, HIM professionals identify areas for improvement that fall under Element Four “Safe Environment for the Delivery of Care”. The final element, “Partnership with Consumers”, is another area where HIM professionals are directly involved. They consider health literacy, flow, and format in the design of clinical forms completed by consumers. HIM professionals are the custodians of health records and have a vital role in protecting patient privacy while supporting access to health information by various parties.

HIM Professionals’ Contribution to Patient Safety

The role of Health Information Management (HIM) professionals in the health system varies. Some HIM professionals are generalists and work across multiple HIM domains, and some specialise in a particular topic or area. Interviews were undertaken with experts in the fields of HIM and patient safety as part of a research project (Kemp et al., 2025) to understand the contribution HIM professionals make to patient safety. These interviews discussed activities related to clinical governance through the functions HIM professionals perform, aligning to Elements Two and Three in the above framework (ACSQHC, 2017), and to Action 1.16 of the NSQHS standards (ACSQHC, 2022). In addition to the examples above, interviews revealed that health information professionals also:

- Review health records to identify deficiencies and generate queries for clinicians to clarify documentation entries.

- Support the management of patient information, clinical records, information systems, and data for accuracy and completeness. Specific examples include managing duplicate records and patient identification mismatches.

- Provide education and training on documentation practices and standards, privacy and confidentiality, information systems, retention, and the disposal of health records.

- Undertake auditing of health records against documentation standards, coding standards, completeness of the health record, data quality, and validation.

- Develop policies and protocols related to health information and records.

- All staff are trained in and required to use the clinical incident management system for reporting incidents, risks, and hazards (Kemp et al., 2025).

In discussing HACs, interviewees specifically discussed that HIMs review health record to accurately capture the patient journey through clinical codes (Kemp et al., 2025). They undertake activities to ensure data are accurate and reliable. They work with clinicians, so they understand the data including how they are collected and used, to identify trends and nuances. Through the capture and provision of data, HIMs help clinicians and health executives understand what is happening in the health system to improve patient safety and quality. The research also identified that HIM professionals work closely with clinical governance departments/teams. Notably, during the interviews, a specific example was reported regarding an incident where a clinician copied and pasted information within an EMR, the risk of this practice, and how it led to patient harm. Importantly, the research highlighted the collaborative working relationships between HIM professionals and those who work in clinical governance or patient safety and quality teams (Kemp et al., 2025).

HIM professionals play an integral role with EMRs, covering information governance, management of the patient master index, merging duplicate patient records, health record structure, ensuring information is in the correct location, documentation improvement, and the implementation of EMRs (Kemp, et al., 2021b). The activities performed by HIM professionals support complete, accurate, and accessible health information for patients, clinicians, health executives, and other users of the information (Kemp et al., 2025). This directly aligns with the requirements of the National Safety and Quality Healthcare Service Standard, Communicating for Safety, which requires healthcare providers to:

- Develop and implement systems to support the contemporaneous documentation of critical information in the healthcare record.

- Record the organisation’s documentation policies and make them available to the workforce.

- Communicate to the workforce their roles and responsibilities for documentation (ACSQHC, 2021).

Activity – Click on each card to identify activities where HIM professionals are involved in patient safety activities.

Conclusion

HIM professionals play a vital role in the health system. They assist others to recognise that the information held within a health record is a valuable resource. EMRs are designed to be accessible and user friendly, with HIM professionals providing oversight for the management and protection of the content, as they also have access to the paper record. HIM professionals extract data used for measuring baselines, progress, and variance in performance indicators, such as those for patient safety and sustainable development goals. HIM professionals continue to ensure that, regardless of the format in which data are collected, the information is available and trusted, and the patient’s story is told.

Activity Fill in the Blanks

References

Accreditation Canada. (2024). Home. Accreditation Canada. Retrieved 05/10/2024 from https://accreditation.ca/

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. (2017). National Model Clinical Governance Framework. ACSQHC;. https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/sites/default/files/migrated/National-Model-Clinical-Governance-Framework.pdf

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. (2019). The State of Patient Safety and Quality in Australian hospitals 2019. https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/sites/default/files/2019-07/the-state-of-patient-safety-and-quality-in-australian-hospitals-2019.pdf

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care. (2025). About Us. ACSQHC. Retrieved 18/05/2025 from https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/about-us

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Healthcare. (2018). Hospital-Acquired Complications Information Kit. ACSQHC. https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/sites/default/files/2019-04/SAQ7730_HAC_InfomationKit_V2.pdf

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Healthcare. (2021). National Safety and Quality Health Service Standards Australia 2nd edition. ACSQHC. https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/sites/default/files/migrated/National-Safety-and-Quality-Health-Service-Standards-second-edition.pdf

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Healthcare. (2022). Action 1.16 Healthcare Records. ACSQHC. Retrieved 10/07/2022 from https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/standards/nsqhs-standards/clinical-governance-standard/patient-safety-and-quality-systems/action-116

Australian Council on Healthcare Standards. (2024). Home. ACHS. Retrieved 05/10/2024 from https://www.achs.org.au/

Brundtland, G. (1987). Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future. http://www.un-documents.net/ocf-ov.htm

Butler-Henderson, K. (2017). Health information management 2025: ‘What is required to create a sustainable profession in the face of digital transformation? (978-1-86295-888-3). U. o. Tasmania. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Kerryn-Butler-Henderson/publication/313315353_Health_information_management_2025_What_is_required_to_create_a_sustainable_profession_in_the_face_of_digital_transformation/links/5895be23a6fdcc32dbd66aab/Health-information-management-2025-What-is-required-to-create-a-sustainable-profession-in-the-face-of-digital-transformation.pdf

Care Quality Commission. (2024). Care Quality Commission. CQC. Retrieved 05/10/2024 from https://www.cqc.org.uk/

Chen, M., Tan, X., & Padman, R. (2020). Social determinants of health in electronic health records and their impact on analysis and risk prediction: A systematic review. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 27(11), 1764-1773. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocaa143

Council for Health Service Accreditation of Southern Africa. (2022). Home. COHSASA. Retrieved 05/10/2024 from https://cohsasa.co.za/

Davis, J., & Shepheard, J. (2024). Clinical documentation integrity: Its role in health data integrity, patient safety and quality outcomes and its impact on clinical coding and health information management. Health Inf Manag, 53(2), 53-60. https://doi.org/10.1177/18333583231218029

Fernando-Canavan, L., Gust, A., Hsueh, A., Tran-Duy, A., Kirk, M., Brooks, P., & Knight, J. (2021). Measuring the economic impact of hospital-acquired complications on an acute health service. Australian Health Review, 45(2), 135-142. https://doi.org/10.1071/AH20126

Global Goals. (2024). Goal 16. The Global Goals,. Retrieved 17/11/2024 from https://www.globalgoals.org/goals/16-peace-justice-and-strong-institutions/

Haute Autorité de santé. (2024). French National Authority for Health (Haute Autorité de santé). HAS. Retrieved 05/10/2024 from https://www.has-sante.fr/jcms/pprd_2986129/en/home

Health Information and Quality Authority. (2024). Home. HIQA. Retrieved 05/10/2024 from https://www.hiqa.ie/

Independent Health and Aged Care Pricing Authority. (2024). Pricing and funding for safety and quality: Hospital acquired complications. Web: IHACPA Retrieved from https://www.ihacpa.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023-01/IHACPA_Hospital_Acquired_Complications_Fact_Sheet.pdf

Institute of Medicine Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. (2000). To Err is Human: Building a Safer Health System. National Academies Press (US). https://doi.org/10.17226/9728

International Federation of Health Information Management Associations. (2021). Revisiting Information Governance. https://ifhimasitemedia.s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/02211552/IFHIMA_IG_OCT2021_DRAFT3.pdf

International Federation of Health Information Management Associations. (2022). Examining Today’s HIM Workforce with Recommendations for Elevating the Profession. https://ifhimasitemedia.s3.us-east-2.amazonaws.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/03/18234714/IFHIMA_Workforce_WP_2022_FINAL.pdf

International Society for Quality in Health Care. (2020). International Society for Quality in Health Care (ISQua) ISQua. Retrieved 05/10/2024 from https://isqua.org/

Joint Commission International. (2024a). Home. JCI. Retrieved 05/10/2024 from https://www.jointcommissioninternational.org/

Joint Commission International. (2024b). International Patient Safety Goals Joint Commission International Retrieved 11/10/2024 from https://www.jointcommissioninternational.org/standards/international-patient-safety-goals/

Joint Commission of Taiwan. (2023). Home. JCT. Retrieved 05/10/2024 from https://www.jct.org.tw/mp-2.html

Kemp, T., Ayton, J., Butler-Henderson, K., & Arabi, S. (2025). Perspectives on the role of health information management professionals in enhancing patient safety: A qualitative study (pre-print). BMC Health Services Research. https://doi.org/10.21203/rs.3.rs-6384767/v1

Kemp, T., Butler-Henderson, K., Allen, P., & Ayton, J. (2021b). Evolution of the Health Record as a Communication Tool to Support Patient Safety. In C. Chisita, R. Enakrire, O. Durodolu, V. Tsabedze, & J. Ngoaketsi (Eds.), Handbook of Research on Records and Information Management Strategies for Enhanced Knowledge Coordination (pp. 127-155). IGI Global. https://doi.org/10.4018/978-1-7998-6618-3.ch008

Kemp, T., Butler‐Henderson, K., Allen, P., & Ayton, J. (2021a). The impact of health information management professionals on patient safety: A systematic review. Health Information and Libraries Journal, 38(4), 248-258. https://doi.org/10.1111/hir.12400

Keshavarz Mohammadi, N. (2022). Complexity-informed approach, sustainable development goals path and social determinants of health. Health Promotion International, 37(3), daac068. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapro/daac068

Liu, S., Kim, D., Penfold, S., & Doric, A. (2022). Clinical documentation requirements for the accurate coding of hospital-acquired urinary tract infections in Australia. Australian Health Review, 46(6), 742-745. https://doi.org/10.1071/AH22155

Lloyd, S., Long, K., Probst, Y., Di Donato, J., Oshni Alvandi, A., Roach, J., & Bain, C. (2024). Medical and nursing clinician perspectives on the usability of the hospital electronic medical record: A qualitative analysis. Health Inf Manag, 53(3), 189-197. https://doi.org/10.1177/18333583231154624

Mansour, W., Boyd, A., & Walshe, K. (2020). The development of hospital accreditation in low- and middle-income countries: a literature review. Health policy and planning, 35(6), 684-700. https://doi.org/10.1093/heapol/czaa011

Mansour, W., Boyd, A., & Walshe, K. (2021). National accreditation programmes for hospitals in the Eastern Mediterranean Region: Case studies from Egypt, Jordan, and Lebanon. The International journal of health planning and management, 36(5), 1500-1520. https://doi.org/10.1002/hpm.3178

National Accreditation Board for Hospitals and Healthcare Providers. (2024). National Accreditation Board for Hospitals and Healthcare Providers: A Constituent Board of Quality Council of India. NABH,. Retrieved 05/10/2024 from https://nabh.co/

Nicklin, W., Engel, C., & Stewart, J. (2021). Accreditation in 2030. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 33(1). https://doi.org/10.1093/intqhc/mzaa156

Our World Data Team. (2023). Ensure healthy lives and promote well-being for all at all ages. OurWorldinData.org. Retrieved 17/11/2024 from https://ourworldindata.org/sdgs/good-health-wellbeing

Saudi Central Board for Accreditation of Healthcare Institutions. (2024). Home. CBAHI. Retrieved 05/10/2024 from https://portal.cbahi.gov.sa/english/home

Schiff, G., & Shojania, K. G. (2022). Looking back on the history of patient safety: an opportunity to reflect and ponder future challenges. BMJ Quality & Safety, 31(2), 148. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjqs-2021-014163

Shaw, T., Hines, M., & Kielly-Carroll, C. I. (2018). Impact of Digital Health on the Safety and Quality of Health Care. ACSQHC. Retrieved 18/05/2025 https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/sites/default/files/migrated/Report-The-Impact-of-Digital-Health-on-Safety-and-Quality-of-Healthcar….pdf

Sittig, D. F., Belmont, E., & Singh, H. (2018). Improving the safety of health information technology requires shared responsibility: It is time we all step up. Healthcare, 6(1), 7-12. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hjdsi.2017.06.004

Stanfill, M. H., & Marc, D. T. (2019). Health Information Management: Implications of Artificial Intelligence on Healthcare Data and Information Management. Yearbook of medical informatics, 28(1), 056-064. https://doi.org/10.1055/s-0039-1677913

United Kingdom Accreditation Service. (2024). Delivering Patient Safety. UKAS. Retrieved 22/09/2024 from https://www.ukas.com/accreditation/sectors/health-social-care/patients/

United Nations. (2024a). Goal 3. United Nations,. Retrieved 17/11/2024 from https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal3

United Nations. (2024b). Goal 16 Targets and Indicators. United Nations. Retrieved 17/11/2024 from https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal16#targets_and_indicators

United Nations. (2024c). Sustainable Development Goals. United Nations. Retrieved 22/09/2024 from https://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/

United Nations Development Programme. (2024). Sustainable Development Goals: Background on the Goals. United Nations Development Programme. Retrieved 30/11/2024 from https://www.undp.org/sdg-accelerator/background-goals

Patient Safety and Quality Improvement Act of 2005, (2005). https://www.congress.gov/109/plaws/publ41/PLAW-109publ41.pdf

Virchow Foundation. (2021). Road to 2030 A brief history of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Virchow Foundation. Retrieved 30/11/2024 from https://virchowprize.org/vf-road-to-2030-history-of-sdgs/

Wilson, R. M., Runciman, W. B., Gibberd, R. W., Harrison, B. T., Newby, L., & Hamilton, J. D. (1995). The Quality in Australian Health Care Study [https://doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.1995.tb124691.x]. Medical Journal of Australia, 163(9), 458-471. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.5694/j.1326-5377.1995.tb124691.x

World Health Organization. (2019). Global action on patient safety. In Seventy-Second World Health Assembly: World Health Organization. https://apps.who.int/gb/ebwha/pdf_files/WHA72/A72_R6-en.pdf?ua=1

World Health Organization. (2021). Global patient safety action plan 2021–2030: towards eliminating avoidable harm in health care. https://www.who.int/teams/integrated-health-services/patient-safety/policy/global-patient-safety-action-plan

World Health Organization. (2024a). Patient Safety: About Us. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/teams/integrated-health-services/patient-safety/about

World Health Organization. (2024b). Social determinants of health. WHO. Retrieved 30/11/2024 from https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health#tab=tab_1

World Health Organization. (2024c). Sustainable Development Goals. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/europe/about-us/our-work/sustainable-development-goals

Image descriptions

Figure 3: A visual summary showing three grouped lists: one with sixteen hospital-acquired complications, another with four health information management (HIM) functions that support tracking and analysis of these complications, and a third titled ‘Impact on Outcomes’ that outlines how these HIM functions contribute to improving patient safety and healthcare quality.

The sixteen hospital-acquired complications (HAC) are:

- Pressure injury

- Falls causing fracture or intracranial injury

- Healthcare-associated infection

- Surgical complications requiring unplanned return to theatre

- Unplanned intensive care unit admission

- Respiratory complications

- Venous thromboembolism

- Renal failure

- Gastrointestinal bleeding

- Medication complications

- Delirium

- Persistent incontinence

- Malnutrition

- Cardiac complications

- Third- and fourth-degree perineal laceration during delivery

- Neonatal birth trauma

The four health information management functions informing HAC monitoring are:

- Information governance (managing/integrity/security/privacy of health data)

- Data quality (ensuring data are correct, reliable, complete, accurate, authentic)

- Clinical coding (reviewing documentation to assign codes reflecting patient journey)

- Reporting (analysing and reporting data to provide information/insights for decision-making)

The five impacts on outcomes are:

- Enables data monitoring and trending of HACs over time

- Supports evidence for benchmarking, decisions, and planning

- Informs artificial intelligence models

- Helps create precision medicine or personal care pathways

- Enables trending prevalence of diseases