Leading the Health Information Service

Sallyanne Wissmann; Sheree Lloyd; and Gina Banfield

Learning Outcomes

- Understand a leader’s responsibilities and behaviours and how they are applied to leading a health information service to achieve its purposes.

- Understand the principles of strategic leadership, performance management, financial management, risk management, functional management, change management, people management, and stakeholder management and how they are applied to leading a health information service.

- Recognise the requirements for an effective health information service, including health record management, information privacy management and compliance, producing accurate timely clinical coded data, maintaining high standards of data quality and reporting, and effective management of health information systems.

Introduction

Health information professionals work in various roles and settings requiring different responsibilities, accountabilities, and spans of control. In this chapter, you will learn about leading the health information service (HIS) within a hospital context; however, the leadership and managerial principles outlined are also applicable in other contexts.

The management of patient data and information is critical to the effective functioning of a healthcare service (Abdelhak & Hanken, 2016; Hardy, 2024). Patient information is routinely collected and created while providing healthcare to a patient (Abdelhak & Hanken, 2016; Hardy, 2024). Healthcare organisations also use and generate data for research, funding, and reporting. Governed by statutory requirements and healthcare standards, patient information needs to be carefully and consciously managed to ensure both compliance and organisational and strategic needs are met within a best practice framework (Abdelhak & Hanken, 2016; Hardy, 2024).

Health information management includes the management of people, processes, and systems associated with patient information. Effective leadership is required to ensure all of these components function optimally to meet patient, organisational, and external needs for patient information.

Leaders hold the ultimate responsibility for the performance of the health information service. They need to set vision and direction, motivate and inspire, make timely and appropriate decisions, be effective communicators, delegate and collaborate, and empower others to succeed within the context of personal accountability, insight, and empathy.

This chapter explores how leadership theories – including strategic leadership, performance management, financial and risk management, and people and stakeholder management – relate to leading the health information service. It also examines how these approaches influence organisational behaviour in the context of health information management.

The chapter examines the core functions of health information services, including health record management, compliance with medico-legal requirements and information privacy laws, clinical coding, maintaining high standards of data quality and reporting, and health information system management.

By addressing these topics, this chapter provides a guide for current and aspiring leaders in health information services, equipping them with the knowledge and skills required to effectively lead the health information service.

The Effective Leader

Leadership is an individual’s ability to influence, motivate, and enable others to contribute to the organisation’s effectiveness and success (Radtke, 2024; Smith et al., 2020a, 2020b)

Contemporary leadership thinking showcases leader behaviours, considering how leaders use personal influence to develop and inspire others in the organisation to develop and inspire people to achieve organisational goals, while also making a difference in the community being served (Olley, 2023c).

Authentic Leadership

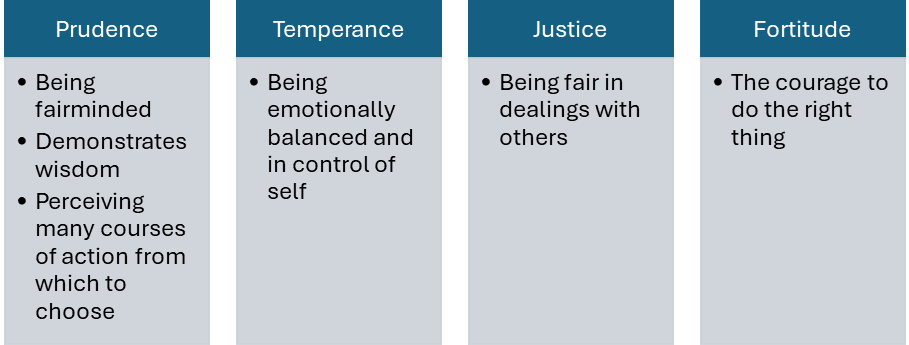

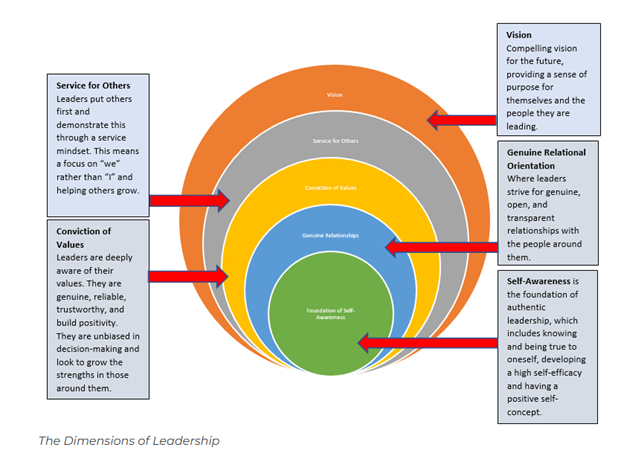

While many leadership theories exist, authentic leadership and ethical leadership theories remain popular. Authentic leaders understand their purpose, practice professional values, establish connected relationships, and demonstrate self-discipline while demonstrating the characteristics shown in the figure below (Olley, 2023c).

Source: Adapted from “The Cardinal Qualities of Authentic Leaders” by Richard Olley (2023c) in The Theories of Leadership, licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

Authentic leaders improve the job satisfaction of those they lead (Braun & Peus, 2016). The following depicts the dimensions of authentic leadership (Olley, 2023c).

Ethical Leadership

Ethical leadership is associated with authentic leadership and is founded upon the practice of leaders’ decisions and deliberations being influenced by moral or ethical considerations (Olley, 2023c). Examples of such decisions include allocating scarce resources, colleague and workforce issues, meeting performance targets, improving organisational culture, disclosure responsibilities, and transparency to identify errors or misadventures (Edwards, 2024; Olley, 2023c). Ethical leadership centres around respect for others’ ethics, values, rights, and dignity; and the leader’s honesty, integrity, trust, and fairness in leadership practice (Olley, 2023c).

Leadership Behaviours

A leader’s behaviour directly impacts the culture of the work team and the delivery of outcomes. Positive leader behaviours cultivate a positive work environment, where team members feel valued, empowered, and equipped to do the work required and can contribute to shared goals of the organisation where they work (Olley, 2023c). Effective leadership behaviours include:

Vision and Direction

Leaders set a clear vision and direction for their team or organisation. They articulate goals and inspire others to work towards them (Olley, 2023c; Radtke, 2024). They also manage the delivery of the vision, sometimes directly or through teams and other individuals, and build and coach teams towards delivery of strategic and operational goals and objectives (Olley, 2023c). The chapter on Leading Strategically in Health Information Management discusses this in further detail.

Influence

A leader’s effectiveness comes from their ability to influence others at all levels of an organisation; hence, the ability to positively influence is an essential leadership skill (Olley, 2023c). It is fundamental to success, providing the impetus for accomplishing team goals and fulfilling team responsibilities (Olley, 2023c).

Empowerment

This is an important act of leadership, to empower others and involves encouraging team members to take ownership of their work. Leaders should support teams by providing the necessary resources and fostering independence and innovation. Delegating challenging tasks and offering mentorship supports team members’ development and confidence (Smith et al., 2020b). The best leaders make a deliberate choice to empower everyone they lead, whoever they are, wherever they are (Boris, 2021).

Timely Decision Making

Leaders are responsible for making important decisions that affect their team or organisation by analysing information, considering alternatives, and choosing the best course of action (Cole, 2024). Leaders will not always get things right, but making timely decisions is effective leadership behaviour. Decisive leaders apply techniques to guide decisions and actively seek out the appropriate information they require to make ethical and sound decisions (Edwards, 2024). Decisive decision making is an important attribute of effective leaders (Cole, 2024).

In any moment of decision, the best thing you can do is the right thing, the next best thing is the wrong thing, and the worst thing you can do is nothing. – Theodore Roosevelt

Effective Communication

Clear and effective communication is crucial for leaders. Leaders must convey their vision, expectations, and feedback to their team and stakeholders and listen to their concerns and ideas. Various communication methods can be utilised to ensure messages are conveyed, understood, and appropriately responded to (Smith et al., 2020b).

Empathy

Empathy is important in leadership because it increases trust, communication, and a sense of worth for team members (Hofmeyer & Taylor, 2021; Jian, 2022).

Growth Mindset

Leaders should both possess and foster a growth mindset, encouraging their teams to embrace challenges, learn from feedback, and persist in the face of setbacks. In comparison to a fixed mindset, a growth mindset fosters continuous improvement and resilience, enabling people to develop their abilities and achieve their full potential (Dweck & Hogan, 2016). This approach not only enhances individual development, but also contributes to the overall success and resilience of the organisation (Dweck & Hogan, 2016).

Lifelong Learning

Effective leaders will engage with ongoing professional development across their career (Hardy, 2024). Lifelong learning is the continuous pursuit of knowledge and skills throughout an individual’s professional life, driven by personal and professional growth. Lifelong learning fosters adaptability, creativity, equips individuals with new and emerging skill requirements, and builds resilience, enabling individuals to thrive in an ever-changing world.

It is encouraging that the development of the specific skills, knowledge, attributes, and abilities required for successful leadership can be learned and enhanced through training, coaching, mentoring and personal growth for existing and emerging leaders (Smith et al., 2020a, 2020b; Olley, 2023).

Health Information Service (HIS) Leaders

A HIS is responsible for the functions associated with patient information in a hospital setting. This extends to influencing how patient information is managed and governed within the organisation. Health information leaders can also work in registries, community health organisations, insurers, government, and information technology (IT companies) (Health Information Management Association of Australia, 2025a, 2025b) This chapter focuses on leadership requirements that can be applied to the HIS, but are also applicable to the different settings where health information leaders are located.

A HIS is usually led by a professional with specialised expertise, skills, and knowledge in health information management. In Australia, degree qualified health information managers collect, classify, and manage health data to meet the medical, legal, ethical, and administrative requirements of health care organisations (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2024). This includes competencies in managing and leading health information services (Health Information Management Association of Australia (HIMAA), 2023).

Leading a HIS includes applying the following areas of leadership and management theory:

- Strategic leadership

- Performance management

- Financial management

- Risk management

- Change management

- Functional management

- People management

- Stakeholder management

A strategic vision, operational expertise, and a commitment to health data and information are necessary to effectively lead a HIS. A proactive, forward-thinking approach is essential to support innovation and lead change. Leaders must stay informed about emerging technologies and advancements, such as artificial intelligence, new classification systems, government and organisational strategies and policies, and new ways of working that can enhance service delivery. A commitment to continuous quality improvement, optimisation of workflows, integration of new digital tools, and adapting to changing organisational and external drivers is essential. To be successful in their role, a HIS leader must demonstrate effective leadership behaviours to gain the trust and respect of staff, leaders, and colleagues. Leaders need to be comfortable with leading and managing change and inspiring others to work towards a common vision for the health information service.

Strategic Leadership of a Health Information Service

Strategic leadership involves setting the strategic direction for a health information service in the context of the organisation’s vision, mission, and strategic direction. Strategic leadership involves keeping informed and involved in organisational change and positively leading resultant change and impacts for the health information service functions and workforce (Smith et al., 2020a). A HIS leader should be involved in the development of relevant organisational strategic plans.

Strategic planning involves identifying risks and considering future internal and external impacts to the health information service and the management and use of its valuable information asset (Hanson, 2011; Lloyd & Craig, 2023).

A HIS strategic plan may be developed as standalone or be incorporated into a broader organisational strategic plan. Either way, it is important that there this a documented vision and strategic intent for the HIS functions for the next 3–5 years.

When developing a strategic plan, key questions for a HIS leader to answer include:

- How does the health information service contribute to the organisation’s strategic aspirations and how will this be articulated?

- What organisational and external changes and drivers will impact health information management and services within the organisation?

- To what extent is the strategic plan visionary, setting a future direction, and inspiring?

- How will progress and success be measured, reported, and celebrated?

It is critical that the strategic plan is developed with team members and internal, and where relevant external, stakeholders, and that operational performance management is aligned with its requirements (Edwards, 2024; Smith et al., 2020a, 2020b).

Strategic leadership involves proactively seeking out information and building relationships with other leaders within and outside the organisation, being curious, and being available to be involved in strategic related conversations and initiatives. To be an effective strategic leader, a HIS leader should have well developed influencing, persuading, and negotiation skills. An effective HIS leader will be respected and sought after for their knowledge and expertise in health information management, including as it relates to digital initiatives (Edwards, 2024; Smith et al., 2020a, 2020b).

Performance Management of a Health Information Service

A HIS leader is required to develop and deliver against operational plans and key performance indicators and be transparent in the reporting of performance as they have accountability for health information both within and outside the health information service (Radtke, 2024; Smith et al., 2020a, 2020b). A HIS leader is accountable for the performance of the health information service. The types of tools that can be used to establish, monitor, and inform performance management include:

Business/Operational Plan

Business and operational plans are used to identify the operational requirements of a HIS. Business plans will include goals or expected outcomes of the service used to assess service performance (Radtke, 2024; Smith et al., 2020a, 2020b). These should be developed with key customers and approved by health service management to ensure they meet the requirements of the health service. Goals should be measurable because they will be used to inform the key performance indicators of the service (Jani & Chaudhary, 2023). Business plans must include the operating hours of the services, resource requirements, and budget. Business plans are usually reviewed annually to identify changes in demand for services that impact operational budgets and priorities such as increased activity or planned capital works in the health service that could impact services and operational demand.

Key Performance Indicators (KPIs)

KPIs are used to measure an organisation’s success or service in achieving their goals. When establishing KPIs, it is important that they are clearly defined and measurable. KPIs should measure the HIS’s productivity and performance to inform progress against the HIS’s business and strategic plans (Domínguez et al., 2019; Radtke, 2024). Consideration needs to be given to identifying the key performance indicators that represent the HIS’s key deliverables, rather than a lengthy list of performance indicators that is cumbersome and time-consuming to measure and report.

HIS Reporting

Regular HIS performance reporting is important for executive leaders, staff, and stakeholders, each of whom has different interests in the data being reported. Reporting demonstrates accountability and commitment to achieving the HIS’s KPIs, operational goals, and strategic objectives. Examples of HIS reporting, depending on the scope of functions of the HIS and the KPIs that are been determined, include:

- Strategic management – the progress of strategic initiatives and projects

- Financial management – performance against the HIS budget

- Risk management – new risks identified, risk mitigation progress

- People management – staff retention, staff engagement, leave, and other human resource (HR) metrics

- Stakeholder management – meeting stakeholders’ needs, key interactions, and working with stakeholders to deliver outcomes

- Operational management – key achievements and key issues, and reporting of KPIs, such as:

- Health records – the volume provided or accessed, scanning volume, completion rates, throughput, and audit results

- Information privacy – the volume by request type, completion rates within KPIs, casemix revenue generated

- Clinical coding – volume, completion rates, throughput (per coder or per hour), casemix acuity, audit results, documentation queries

- Data quality and reporting – duplicate registrations, key data quality metrics, reporting deadlines status

In Australia, My Health Record compliance often falls under the jurisdiction of a HIS leader, and compliance audit results in line with legislated requirements are reported to health service executives regularly to ensure ongoing access to health record information (Australian Digital Health Agency, 2024).

Financial Management of a Health Information Service

A HIS leader oversees the financial management of the health information service. This includes setting and managing budgets, developing business cases for capital expenditure, and contributing to the organisation’s financial management through management of components of the organisation’s funding model (Edwards, 2015; Radtke, 2024).

Health Information Service Financial Management

Effective financial management and budgeting are necessary to ensure the sustainability and efficiency of HIS operations, as appropriate operational and resource models are dependent on available funding.

Budgeting provides a structured approach to planning and controlling financial resources. A comprehensive budget allows for funds to be allocated where and when required and to ensure essential health information functions are delivered. Budgeting should be undertaken in accordance with organisational policies and guidelines. The annual budget process enables operational planning to be informed through changes planned within the organisation that may impact on the demand for health information services (Edwards, 2015). Monthly monitoring of financial performance and labour metrics against budget is necessary to understand any variations in and the rationale for the financial results. Health information services may require capital funds for items such as new/refurbished/expanded office or storage space, new information systems or system upgrades, or new/replacement equipment (Edwards, 2015).

Capital expenditure usually requires the preparation of a business case to justify the capital spend in terms of outcomes and benefits, total cost of ownership, and return on investment. Considerations should include the project duration, human resources required, equipment or system configuration, testing and implementation, infrastructure requirements, software licences, and impacts on current and ongoing operational costs (Edwards, 2015).

HIS leaders should be the authors of their business cases and should review all organisational business cases that have an impact on health information management and governance (Smallwood, 2018).

Organisational Financial Management

A health information service provides data required for several strategic purposes including the organisation’s receipt of activity-based funding. Activity-based funding in healthcare is a model where hospitals receive payments based on the quantity and variety of patients they care for (Independent Health and Aged Care Pricing Authority, 2025). For admitted patient activity, diagnosis related groups are required for activity-based funding, which is an outcome of the clinical coding process (Independent Health and Aged Care Pricing Authority, 2025). As a result, the accuracy and timeliness of items such as principal diagnosis, complications, co-morbidities and treatments required for coding and diagnosis related groups assignment is imperative (Health Information Management Association of Australia, 2024). These items are dependent on the quality and comprehensiveness of clinical documentation and attracts significant attention. For non-admitted patient care, the accuracy and timeliness of data reporting contributes to funding dependencies (Independent Health and Aged Care Pricing Authority, 2025). A HIS leader needs to understand the data dependencies for the organisation’s funding model where it relates to patient information and ensure all associated processes are efficient and provide accurate data.

Risk Management for Health Information Services

A HIS leader has a responsibility to identify and escalate organisational risks associated with health information, and to actively mitigate existing risks (NEJM Catalyst, 2018). Health information risks can lead to consequences such as patient harm, compliance breaches, loss of revenue, and reputational damage for the organisation if not effectively mitigated.

It is critical that a HIS leader is conversant with the organisation’s risk management policy and requirements. This is expected to be consistent with ISO 31000, an international standard that provides principles and guidelines for risk management (International Standards Organisation, 2018). ISO 31000 outlines a comprehensive approach to identifying, analysing, evaluating, treating, monitoring, and communicating risks across an organisation. HIS leaders are encouraged to be familiar with ISO 31000 and their organisation’s risk management policy and procedures.

Strong governance including risk management is essential for the management of information and data due to the sensitive nature of health data and the increasing risks of cybercrime, data theft and the potential harm that these cause to individuals and health care organisations (Smallwood, 2018) (see other chapters for further information such as Cybersecurity in Health). Management of the information and data assets within healthcare organisations is key to controlling the risks associated with data loss and the protection of staff and consumer privacy. Good corporate governance systems should include information, data governance, and risk management (NEJM Catalyst, 2018).

The following table provides an example of a simple risk management plan to illustrate a risk management approach for the introduction of an information system:

HIS leaders will identify, assess, and mitigate risks associated through the management and use of information assets. This involves conducting risk assessments to identify potential threats to data integrity, security, and availability, and evaluating the likelihood and potential impact of these risks. Information governance frameworks incorporate risk management practices to develop strategies for minimising risks, such as implementing controls, establishing contingency plans, and regularly monitoring and reviewing risk exposure to ensure ongoing effectiveness. Effective, information governance involves collaboration across organisational departments and functions such as IT, health information management, legal/compliance, executive, clinical teams, and business units (Hardy, 2024; Hovenga & Grain, 2023) . It requires a combination of policies, training, technology, ongoing monitoring, and enforcement, to manage information through its lifecycle (creation and capture to storage, retrieval, and disposal). Maximising data assets while mitigating risks such as improper data handling requires input from clinical, professional staff and executive stakeholders.

Examples of HIS risks include:

- Breach of privacy due to missing patient records or data, inappropriate access to patient information, or non-approved disclosure.

- Theft of patient information due to cyber-attack. The risk of cyber-attacks on health services is on the rise with approximately half of the world’s hospitals experiencing an IT shutdown due to a cyberattack in the first half of 2021 (PwC Australia, 2022).

- Computer downtime interrupting hospital and HIS services mitigated with robust downtime procedures.

- Availability of staffing resources, including clinical coding and administrative teams.

- Physical damage to patient records or patient record departments where a physical record still exists. An example of this would be a water leak due to a burst pipe resulting in wet records and water damage to paper.

Change Management

Change management is the “…process, approach and set of tools for managing the people side of change so that business results are achieved, on time, and within budget – combines project management and human behaviour” (Health Information and Management Systems Society)

The introduction of new classification systems, health information solutions, digital health initiatives, and new procedures and policies often requires significant changes within healthcare organisations. Contemporary organisational theory argues that the culture and structure of some organisations are more conducive to change than others and that health organisations are not of the type where change is easily implemented (Braithwaite et al., 2017; University of Minnesota, 2017). Digital disruption, innovation and transformation are increasingly common in health organisations (Almond & Mather, 2023).

Change is inevitable in healthcare and industries. Many changes fail for reasons such as poor planning, change-fatigued or unmotivated staff, deficient communication, or excessively frequent changes (Dendere et al., 2021; University of Minnesota, 2017).

Due to the challenges associated with change, HIS service leaders and managers understand that too much change or change that is too rapid can impact the workforce, resulting in fatigue, low morale, and dissatisfaction.

All healthcare providers, from the bedside to the boardroom, have a role in ensuring effective change. Using the best practices derived from change theories can help improve the odds of success and subsequent practice improvement (Barrow & Annamaraju, 2025).

Change Models

There are many theories and models for change management. No single change theory is considered “right”. Current thinking is that change needs to be understood and tailored to fit the specific needs of an organisation within its cultural, economic, and political context (Barrow & Annamaraju, 2025; Day & Shannon, 2015).

Change can be planned, emergent, or adaptive. Planned change involves moving from one state to another in a structured manner. The implementation of an electronic medical record would be an example of planned change. However, depending on the scope and breadth of changes to workflows, structures, processes, and culture could also involve transformation (Barrow & Annamaraju, 2025; Day & Shannon, 2015).

An alternative is to see change as fluid and emerging, as it is pervasive and continuous. Taking this view means you are more likely to manage change as part of what happens naturally in an organisation and see interventions as cyclical or iterative. This is commonly referred to as “emergent change”. Adaptive changes are those small, incremental adjustments that individuals, teams, organisations, managers, and leaders to adapt to daily, weekly, and monthly challenges. When we make adaptive changes, they are usually related to fine tuning of existing processes and will not impact upon the organisation.

Planned change approaches rely more on assumptions that an organisation’s environment is known. Change can then be planned to facilitate movement from one condition to another. In contrast, emergent change emphasises the need to be responsive and adaptive: that change is constantly around us. It may be that some changes can be seen as more stable and predictable moving from one state to another, while other change is more on-going.

Concepts including change vision, barriers and supporters, leadership, goals, and action plans are well documented within change theory. Depending on the type of change, it is normal to choose a change model or framework on which to base the approach and this can provide a stronger chance of success (Harrison et al., 2021). There are many different models, with common change approaches described below.

Lewin’s 3 Step Model

This simple model has high appeal with three-steps to change behaviour using the metaphor of melting and reshaping an ice cube. Lewin’s model proposes that behaviours need to be unfrozen, changed to the desired state and refrozen to the new state and desired behaviours (Day & Shannon, 2015; University of Minnesota, 2017).

ADKAR Model (Awareness, Desire, Knowledge, Ability and Reinforcement)

This is a model developed by Prosci founder Jeff Hiatt after studying the change patterns of more than 700 organisations. This is a people-centred approach designed to facilitate change at the individual level (Prosci, n.d.).

Kotter’s (2021) Eight-step Change Model

This is the most well-known change model. It is used to reduce resistance and accept change. Kotter’s model has evolved and has an eight step methodology [opens in new tab].

- Creating a sense of urgency

- Build a guiding coalition

- Form a strategic vision

- Enlist a volunteer army

- Enable action by removing barriers

- Generate short-term wins

- Sustain acceleration

- Institute changes (Day & Shannon, 2015; Kotter, 2021).

Plan, Do, Check, Act (PDCA)

This model involves a cyclical and iterative change management process focused on continual improvement and is suitable for small improvement projects and can allow stakeholders to work together to incrementally improve systems and processes (Chen et al., 2021).

Service Redesign

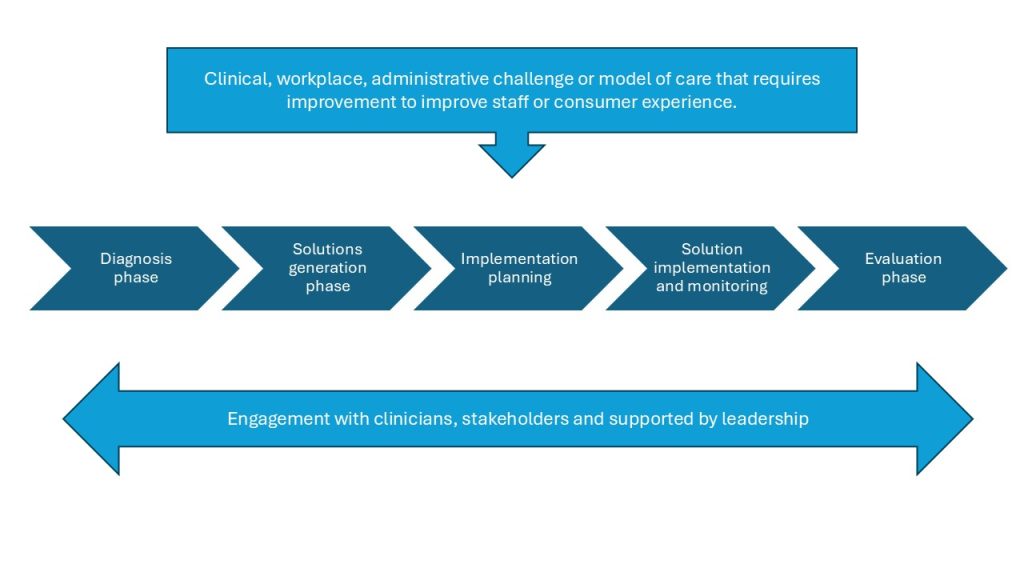

Service redesign and clinical redesign are used to identify the cause of challenges and determine evidence-based solutions. Service redesign is fundamentally underpinned by working with those who know the work best or are impacted (clinicians, staff, and consumers) to determine the causes, reasons for delay, barriers, and enablers to care and service provision (Ben‐Tovim et al., 2008). Redesign also recognises that problems may be the result of poor overall design and disconnections between the stages of care that might cross multiple departments (Ben‐Tovim et al., 2008). Service redesign follows several steps, including diagnosis, solution design, detailed implementation planning and planning, and rollout of solutions. Service redesign is a proven and valid approach to change (Ben‐Tovim et al., 2008). The diagram below shows the steps in service redesign.

Source: Adapted from Box 4 “The phases of clinical process redesign” in Ben-Tovim et al. (2008). [Go to image description]

Activity – Service Redesign

Step 1: Read Patient journeys: the process of clinical redesign [opens in new tab]

- Summarise the key stages of clinical redesign as described in the article:

- Engage

- Diagnose

- Design

- Implement

- Sustain

- Reflect on how these stages relate to your current or future role.

Step 2: Select a patient journey with complex information flows.

Choose a patient journey relevant to your context.

Examples:

- Elective surgery pathway

- Outpatient bookings

- Mental health intake and referral

- Chronic disease management (e.g., diabetes)

Step 3: Map the information flows:

- Where and how patient data is collected (e.g., ED triage, imaging, nursing notes)

- How it moves between departments

- Points where data is delayed, duplicated, or lost

- Systems involved (e.g., EMR, paper forms, verbal handovers)

Step 4: Identify Redesign Opportunities (15 minutes)

For each weak point in the information flow, ask:

- What causes the breakdown?

- How does it impact patient care or staff efficiency?

- What redesign could improve it? (e.g., automated alerts, shared dashboards, standardised forms)

Step 5: Implementation Planning

Outline a basic plan for implementing one of your redesign ideas:

- Stakeholders involved

- Resources needed

- Potential barriers and how to address them

- Metrics for success

Step 6: Reflection

Write a short reflection (300–500 words) on:

-

- What you learned about service redesign

- How this process could improve patient outcomes and staff satisfaction

- How you might apply this in your workplace or studies

Management of Health Information Service Functions

A HIS leader is responsible for ensuring that health information functions are efficient, timely, accurate, and effective (Health Information Management Association of Australia, 2025a, 2025b). The organisation will determine the functions required of the health information service and these will vary depending on size, location, and the types of healthcare services delivered. These functions may expand and constrict over time.

A HIS leader must understand legislative and compliance requirements and guide how patient information is created, accessed, used, stored, and retained throughout its lifecycle. The management of health data is a critical responsibility of a health information service. A HIS leader needs to ensure that health information systems are robust, secure, and compliant with regulations, policy, and guidelines. HIS leaders are actively involved in health law and ethics, and work to address legal and ethical issues related to health information, including health records and the use of health information systems.

The delivery of HIS functions will be impacted by organisational policy, available technology, regulatory requirements, and other internal and external factors. A continuous improvement and change-receptive approach is required to continue to adapt and mature HIS functions.

A HIS leader needs to be aware of the following sources of regulatory compliance that may apply to the HIS functions dependent on the location of the service and type of healthcare organisation:

- Commonwealth legislation

- State/territory legislation

- State/territory government policy, directives

- National Safety and Quality Health Service Standards

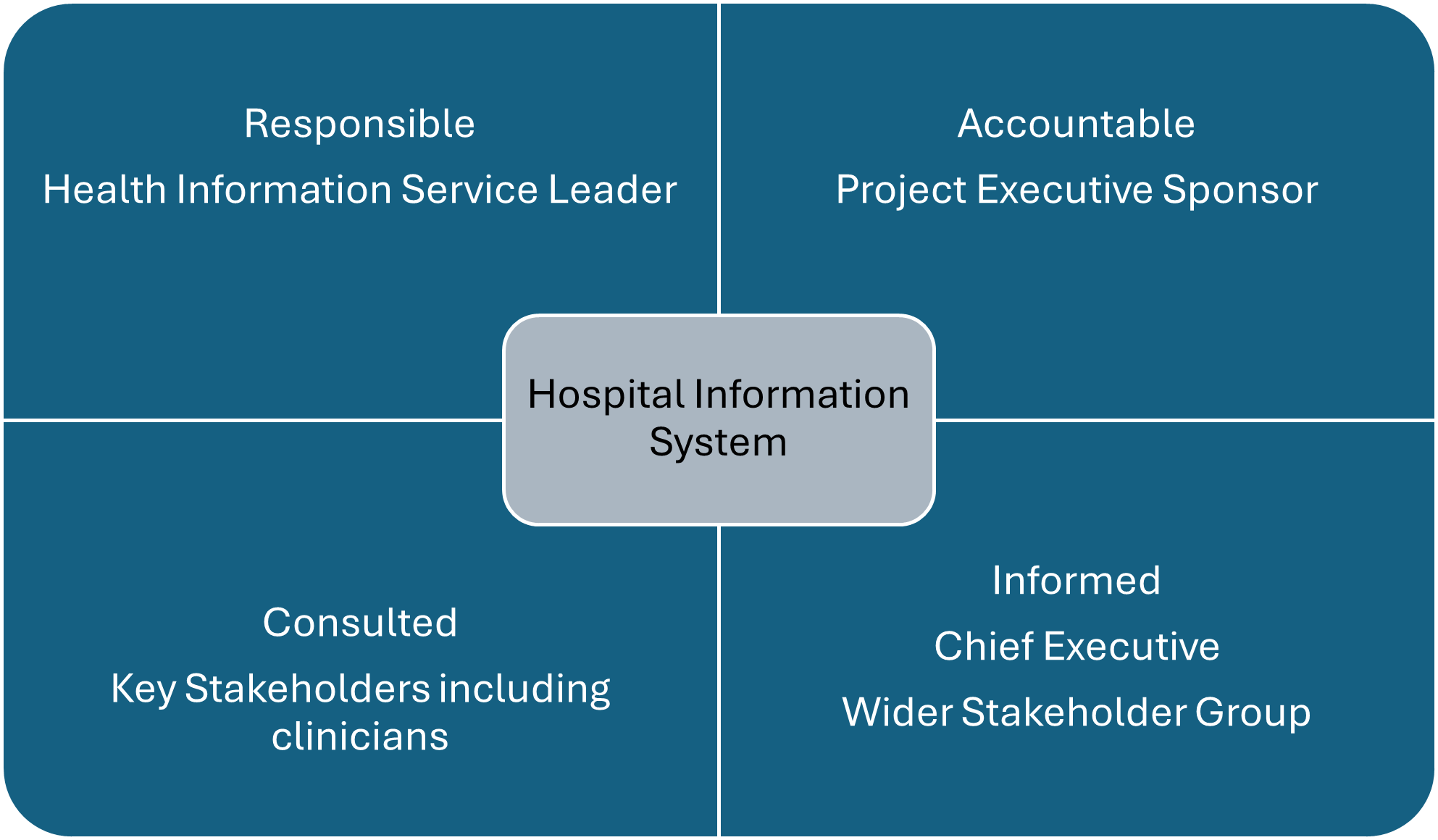

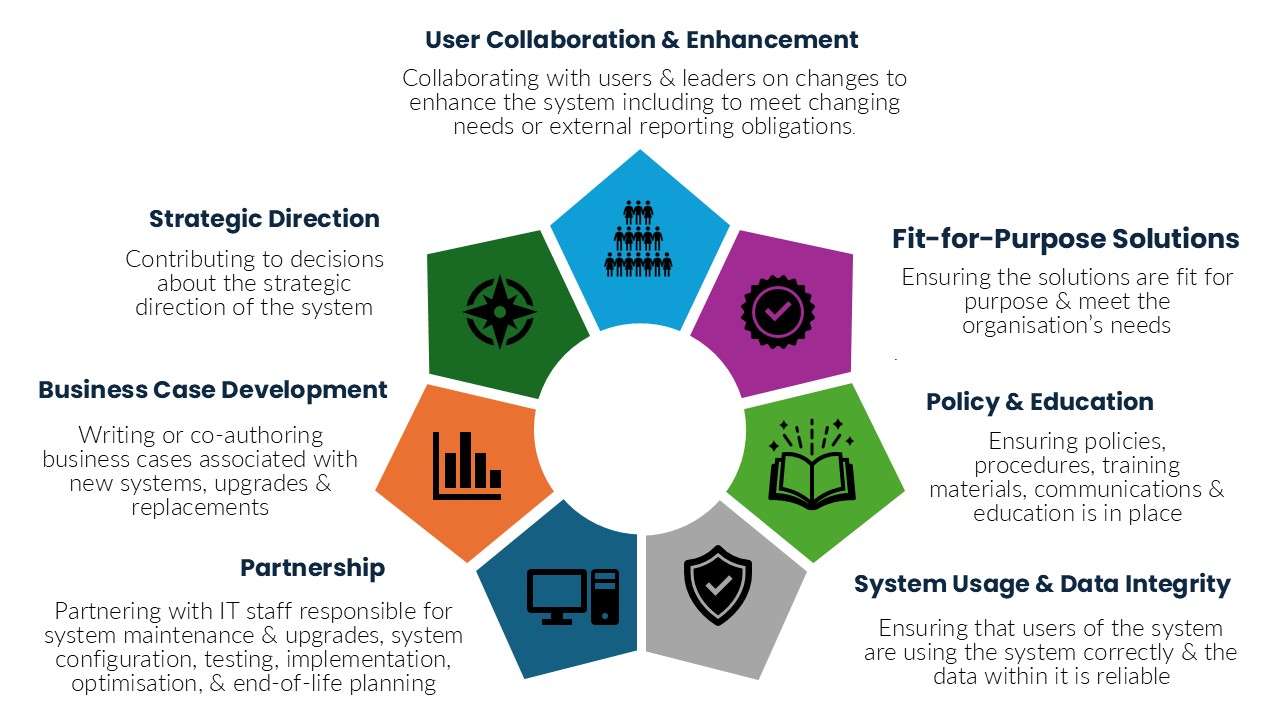

It is recommended that HIS functions are managed through the mechanisms shown in the diagram below:

There is no singular approach to the reporting line of a health information service within healthcare organisations. The executive role responsible for the HIS may vary between clinical services, finance, and/or IT/digital services. Within some organisations, the functions of a health information service may be split under different executive portfolios. When this occurs, increased collaboration is required to ensure seamless cooperation between the different teams to meet their respective outcomes.

A HIS leader needs to collaborate with the health service executive to determine the extent of accountability and responsibility they have in relation to health information functions within the organisation. A Responsibility Assignment Matrix , or RACI matrix (which identifies those Responsible, Accountable, Consulted, and Informed) is a useful tool for this purpose (Smallwood, 2018). A HIS leader will often be given the responsibility of custodian, that is, on behalf of the organisation, they are to take care of, apply and mature governance and assurance to information management disciplines and artefacts such as health records, information privacy and health data and information governance. An example RACI matrix for the implementation of a new health information system is shown below:

The typical functions of a hospital health information service are:

- Health record management

- Information privacy management

- Clinical coding

- Data quality and reporting

- Health information system management

Additional functions, not covered in this chapter, may include:

- Clinical transcription

- Clinical documentation improvement

- Information governance

Health Record Management

A health record is the collection of data and information gathered or generated to record the clinical care and health status of an individual or group (AS 2828.1: 2019) (Standards Australia, 2019a, 2019b).

A healthcare record includes a record of the patient’s medical history, treatment notes, observations, correspondence, investigations, test results, photographs, prescription records and medication charts for an episode of care (Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Healthcare, 2021). Essential information is documented in a healthcare record to ensure patient safety (Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Healthcare, 2021).

A health service organisation needs to have healthcare record systems that:

- Make the healthcare record available to clinicians at the point of care

- Support the workforce to maintain accurate and complete healthcare records

- Comply with security and privacy regulations

- Support systematic audit of clinical information, and

- Integrate multiple information systems, where they are used (Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Healthcare, 2021).

A health record may be in one or more formats including:

- Paper

- Digitised – A health record produced by converting source records into digital format (AS2828.2:2019) (Standards Australia, 2019b).

Some health record services undertake the scanning of paper clinical documentation to convert it to scanned images for subsequent access and retention purposes. This requires comprehensive quality controls to be put in place.

- Electronic – An electronic health record is a health record with data structured and represented in a manner suited to computer calculation and presentation (AS 2828.1: 2019) (Standards Australia, 2019a). You can read further about this topic in this chapter Electronic Medical and Health Records.

Best practice is to have a single health record for a patient, where all health information pertaining to the patient is available across all episodes of care for the healthcare organisation. If patient information is retained in multiple formats, these should be integrated into a single accessible patient health record via the most appropriate format.

The processes that need to be created, maintained, and managed for appropriate health record management include:

- Health record definition, creation, and content

- Health record register of health record components

- Authorised health record systems and position on collaboration and AI systems

- Health record internal request and access

- Health record management

- Health record retention and disposal

- Deceased patient notification

- Clinical forms management

- Patient alert management

- Clinical photography and clinical image management

- Electronic signatures

Information Privacy Management

Other chapters in this textbook explain the concepts and importance of information privacy and the risks of cybersecurity as it relates to health information. See chapters on Health Information Law, Privacy and Ethics, Cybersecurity in Health and Cyber Risk Management.

The processes that need to be created, maintained, and managed for appropriate information privacy management include:

- Information privacy policy

- Information privacy procedures, including release of information processes for all request types

- Managing a notifiable data breach incident

- Privacy impact assessment

- Information classification

- Personal information collection notification statement

- Patient information consent forms, including consent to clinical imagery

- Health information and system access, including for students and volunteers

- Use of generic vs named logins

- Use of patient data for system testing purposes

- Sharing information securely with external third parties. This may necessitate the need for legal agreements to be in place between parties.

- Advanced health directives, enduring power of attorney, and Office of the Adult Guardian

- Research requests

It is recommended that a mandatory education training module is created and made available to all staff within the organisation in relation to their information privacy obligations.

Clinical Coding

Clinical coding using the ICD-10-AM/ACHI/ACS classification system is undertaken for all admitted care in Australia (Independent Health and Aged Care Pricing Authority, 2025). Clinical coding is the assignment of codes that reflects clinical documentation following the application of the conventions, standards and rules used with a health classification system (Health Information Management Association of Australia, 2024). Abstraction involves the review and appraisal of clinical documentation to determine whether the assignment of relevant code(s) is warranted, or if there is vagueness or conflicting entries in the health care record that need to be clarified by the clinical author (Health Information Management Association of Australia, 2024). You can read further about Healthcare Classification and Terminologies in this chapter.

The Clinical Coding Practice Framework [opens in new tab] provides a structure for those managing health services to support their workforce of clinical coders, clinical coding auditors and educators, health information managers, clinical documentation improvement specialists and other health information management professionals in producing high-quality clinical coded data (Health Information Management Association of Australia, 2024).

The processes that need to be created, maintained, and managed for appropriate clinical coding management include:

- Clinical coding process

- Clinical coding staffing plan

- Clinical coding audit strategy to ensure the quality of coding is of the required standard

- Clinical coding training and education framework

- Clinical documentation audit framework to ensure the clinical documentation reflects the care provided and meets the requirements for clinical coding accuracy

- Patient record audits to ensure all the required information is available to the clinical coding team within the timeframes required of the service.

Data Quality and Reporting

Data quality and reporting primarily concerns ensuring accurate and complete data are available for priority data items that are critical to patient care and internal and external reporting and analysis. Areas of focus often include:

- Patient registration and identification data

- Admitted patient data

- Non-admitted patient data

- Clinical data required to be reported for statutory purposes

Australian hospital reporting requirements include reporting to the:

- National Hospital Morbidity Database (public and private admitted activity)

- National Perinatal Data Collection (pregnancy and childbirth)

- Hospital Casemix Protocol (privately insured episodes)

- Private Hospital Data Bureau (private hospital admitted activity)

- State and National Cancer Registries

- Trauma, Injury and other Registries

- Benchmarking partners and organisations

- Safety and quality indicators

Reporting requirements will vary from country to country and parts of the healthcare system (primary care, rehabilitation, mental health).

The processes that need to be created, maintained, and managed for appropriate data quality and reporting include:

- Data governance plan

- Data quality requirements and audit plan

- Data sources and data map

- Data retention plan

- External reporting register

Health Information System Management

A HIS leader is often given the responsibility of being the business owner of one or more key systems that hold or process patient information.

Examples of such systems include:

- Patient Administration System

- Patient Master Index

- Health Record Scanning System

- Clinical Coding Systems

- Health Provider Directory

- Clinical Portal

- Patient Portal

- My Health Record

- Transcription Systems

- Electronic Health Records

As the business owner of an information system, a HIS leader plays a role in making sure the system meets organisational needs and evolves to meet new requirements. They are responsible for ensuring that the system’s processes and solutions are suitable and remain effective over time. This includes making sure that the right policies, procedures, training materials, and communication tools are in place so that everyone understands how to use the system properly.

A HIS leader also ensures that users are using the system correctly and that the data entered are accurate and trustworthy. They work closely with users and their leaders to identify necessary changes and set priorities for improving the system, especially when the organisation’s needs change or when new legislative or reporting requirements emerge.

A HIS leader contributes to broader decisions about the system’s strategic direction. They collaborate with IT teams on system maintenance and upgrades, testing, implementation, optimisation, and planning for when new systems are required or current systems need to be replaced. When upgrades or replacements are required, a HIS leader may also write or help write business cases to support those changes (Hovenga & Lloyd, 2006).

The breadth of health information management professional responsibilities is shown in the figure below.

Figure 7. Health Information Manager Responsibilities. [Go to image description]

Processes that need to be created, maintained, and managed for appropriate management of health information systems include:

- Policies and procedures examples include:

- Patient identity and registration

- Health provider identification and registration

- System access and training

- System downtime procedures and forms

- System management plan including decommissioning

- Training materials

A HIS leader is well positioned to be an operational sponsor and key advisor for digital health projects. This involves writing and/or reviewing business cases, being involved in system selection, being part of project steering committees, providing guidance to the project manager and team, raising risks, and contributing to the project’s success.

My Health Record

In Australia, the My Health Record is the secure online summary of a consumer’s health information, managed by the system operator of the national My Health Record system (Australian Digital Health Agency, 2024). Clinicians can share health clinical documents to a consumer’s My Health Record, according to the consumer’s access controls. These may include information on medical history and treatments, diagnoses, medicines, and allergies.

In relation to the My Heath Record, the National Safety and Quality Health Service Standards (Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Healthcare, 2021) mandate the following:

The health service organisation works towards implementing systems that can provide clinical information into the My Health Record system that:

- Are designed to optimise the safety and quality of health care for patients

- Use national patient and provider identifiers, and

- Use standard national terminologies AND

The health service organisation providing clinical information into the My Health Record system has processes that:

- Describe access to the system by the workforce, to comply with legislative requirements, and

- Maintain the accuracy and completeness of the clinical information the organisation uploads into the system

The My Health Records Act (Australian Government, 2012) prescribes a number of requirements for health service organisations who access and/or send patient information to the My Health Record. Health information services oversee this process.

People Management for Health Information Services

“One of the criticisms I’ve faced over the years is that I’m not aggressive enough or assertive enough, or maybe somehow, because I’m empathetic, it means I’m weak. I totally rebel against that. I refuse to believe that you cannot be both compassionate and strong.” Jacinda Ahern, 40th Prime Minister of New Zealand

Leading a multidisciplinary team is central to the role of the health information service leader. This involves continuous workforce planning, recruiting skilled coding and other professionals, and ensuring that staff are trained and have opportunities for ongoing professional development (Williams & Archdall, 2015). Modern workforce requirements require leaders to effectively lead intergenerational and diverse teams and to ensure safe and healthy work environments both onsite and at remote working locations (Dols et al., 2010; Sequeira & Aish, 2023).

Australia is facing a significant workforce shortage for many healthcare workers, including health information management, driven by an ageing workforce and lack of supply of qualified health information managers (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2025). This leads to additional demands on workforce planning and the configuration and management of the staff mix required to meet service needs. The shortage of health information professionals and clinical coders exacerbates the healthcare system’s ability to manage and utilise health data effectively.

The following are the key attributes of people management that need to be considered and managed to lead the health information service:

- Workforce Planning

Workforce planning includes determining the resource profile, budget, and sourcing of human resources required to achieve the outcomes required (Olley, 2023b). The resource profile includes determining what types of skills and competencies, responsibilities, and roles are required, how much work each role can achieve, and how many of each resource type is required. This will often require the collection of data and other evidence to justify the resource profile and is an ongoing activity (Olley, 2023b; Williams & Archdall, 2015).

A knowledge of relevant industrial awards and instruments is important to determine the budget required for each role, as well as the organisation’s policies in relation to human resource management (Williams & Archdall, 2015). There are often budget constraints in relation to human resources highlighting the importance of role justification. A business case may need to be written to justify additional resources being included in the budget.

There are several options for sourcing the people required, including full-time, part-time, or casual employment, or contractors. Factors to consider include workforce stability and the risk of workforce turnover.

- Intergenerational and Diverse Workforce Management

Recent HIM workforce studies has identified an aging workforce, with the majority of the workforce identifying as female (Marc et al., 2019). This can present challenges for managers when responsible for a workforce that is intergenerational and diverse (Briggs & Isouard, 2015). The importance of managing intergenerational relationships in the workplace is critical in preventing agism and ensuring knowledge and expertise of the older workforce is not lost to the organisation (Wu et al., 2025).

- Training, Education, Professional Development and Career Development

Training and education programs are important components of maintaining a workforce that is high performing and can provide accurate data and information. These programs need to ensure the workforce remains current with the latest standards and legislative requirements (Olley, 2023a; Patterson et al., 2023).

Professional development and career development in the workplace ensure employees feel valued and understand the career pathways available, leading to an engaged and professional workforce (Olley, 2023a; Patterson et al., 2023).

- Safe and Healthy Work Environments

Workplace health and safety is a legislative requirement in Australia, and although the legislation differs from state to state, the overarching principles are the same. Health information services need to ensure ergonomic factors are assessed and plans are in place to ensure staff are safe from injury, including manual handling techniques and training to avoid repetitive strain injury (Sequeira & Aish, 2023). Psychological safety in the workplace is increasingly important. Individuals should feel comfortable expressing themselves and sharing ideas or concerns without fear of rejection, or punishment.

The evolving hybrid working model where team members can work remotely or onsite presents its own challenges. The employer is still responsible for workplace safety, irrespective of where the work takes place. Policies for remote working need to include minimum standards for desk set up and workplace safety. These are evaluated against remote working audit tools with photographic evidence provided of the work setting and compliance. These audits should occur annually or when there is a change in location (NSW Health, 2025).

Health Information Service Workforce

Health information services may have different staffing models depending on the health services and work environment. Health information services may be managed as standalone units, or their management structure may be part of a larger network of hospitals. The typical roles and key functions of HIS staff are:

Health Information Managers

As we have seen, degree qualified health information managers collect, classify, and manage health data to meet the medical, legal, ethical, and administrative requirements of health care organisations (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2024). They have competencies in relation to professional skills; health information science, including health records management, language of medicine, and healthcare; healthcare classifications and terminologies; research methods; health data analytics; organisation and delivery of health services; health information law and ethics; health informatics and digital health; and organisation and management of the health information service (Health Information Management Association of Australia, 2025a, 2025b; Health Information Management Association of Australia (HIMAA), 2023). As a result, they are equipped to undertake any of the functions and roles within the health information service including managerial and leadership roles.

Medical Record Officers or Health Information Officers

Medical record officers are responsible for managing paper and scanning health record processes, providing patient records to clinicians for patient care or for secondary uses such as research or quality audit. These teams are comprised of administrative workers who undergo on the job training. The increasing use of technology requires the workforce to be computer literate and work across multiple systems.

Privacy Officers

Privacy officers respond to enquiries and requests for patient information in accordance with organisational policies and procedures and under the supervision of a suitably experienced manager.

Clinical Coders

The clinical coding workforce can include both HIM qualified and diploma (or equivalent) staff. The use of activity-based funding across both public and private sectors has increased the need high standard of clinical coding driven by a qualified and well-trained workforce.

The population is aging, increasing the burden of chronic disease (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2025), and there is a current workforce shortage. Management of the clinical coding workforce has its challenges, with the increasing demand for data to inform funding models and service planning the clinical coding teams are often caught between high volume versus timely and accurate coded data. When managing these teams, it is necessary to provide the balance between demand, quality, and resources, ensuring senior management is aware of any shortfall in resources that could impact the productivity of the team (Briggs & Isouard, 2015).

In the private sector, external coding audits by health funds are used to assess the quality of the coded data to ensure insurance claims are an accurate reflection of the care provided. This can be intimidating to the coding teams, and it is the manager’s responsibility to support teams through the process and ensure any learnings from the audit are presented to the team in a constructive and positive way.

Coding Educators

Coding educators are responsible for training clinical coders from graduate level through the stages of their career development. This may either be a component of a coding manager role, a standalone role, or be part of a role that supports multiple hospitals and coders.

Coding Auditors

Coding auditors are responsible for conducting audits on completed clinical coding for quality assurance purposes. Given the dependency on quality clinical coded data for funding purposes, and the constraints associated with re-submission of coded data to private insurers, it is critical that clinical coding is accurate prior to billing and other secondary uses occurring. System based criteria should be used to identify the priorities for audit. Investment to address source issues of poor-quality coding outcomes needs to occur.

Data Quality/Reporting Officers

Data quality/reporting officers are responsible for identifying data quality issues, liaising with authors of the data for correction, identifying system edits and flags that can improve data quality, cleansing data, preparing data for reporting, and reporting data to authorised third parties.

Stakeholder Management for Health Information Services

Health information systems and digital health technologies—such as electronic health records, telehealth, wearables, artificial intelligence, patient portals and health information exchanges—offer significant potential to improve care quality, safety, and efficiency, their implementation often encounters resistance (Adjekum et al., 2018; Almond & Mather, 2023). This resistance can stem from the diverse and sometimes conflicting perspectives of stakeholders across the healthcare ecosystem. Please read further here about Engaging with Stakeholders and Partners.

Stakeholders include consumers, families, carers, clinicians, health service managers, IT vendors, policymakers, funders, and the broader community (Brownie & Holmes, 2015). Each group brings unique expectations, concerns, and levels of readiness for change. Although the technical components of health information system solutions are often well-executed, the human and organisational aspects—such as change management, communication, and training—are often not well addressed. When change is not managed well, and people are not involved, there is potential for failure and suboptimal achievement of intended benefits and anticipated value (Hovenga & Lloyd, 2006). A HIS leader needs to balance and set realistic expectations of the intended benefits of any new health information system or technology.

Effective stakeholder engagement is essential from the earliest stages of health information initiatives. This includes structured consultation processes to explore how health information will be used, who will use it, and what new workflows or services will emerge. These discussions help clarify expectations, assess readiness for change, and align the intended benefits of digital solutions with stakeholder needs.

The goal of stakeholder engagement is to build consensus and co-create a shared vision for the digital health initiative. Achieving this consensus is critical to navigating the complexities of Australia’s health system and balancing diverse priorities. A foundational step in this process is stakeholder analysis—identifying who is affected, their level of influence, and how best to involve them. This analysis should inform all phases of the project, from strategic planning and system design to implementation and evaluation.

A health information service leader routinely collaborates with a broad range of stakeholders with varying needs and complexity including information technology, vendors, senior organisational leaders, clinicians, and government. They need to be able to effectively influence administrative and clinical staff to adhere to health information policies and procedures.

While engaging with stakeholders and partners is discussed in another chapter in this textbook (Engaging with Stakeholders and Partners), it is important to recognise that stakeholder engagement and management needs to be a high priority for the HIS leader.

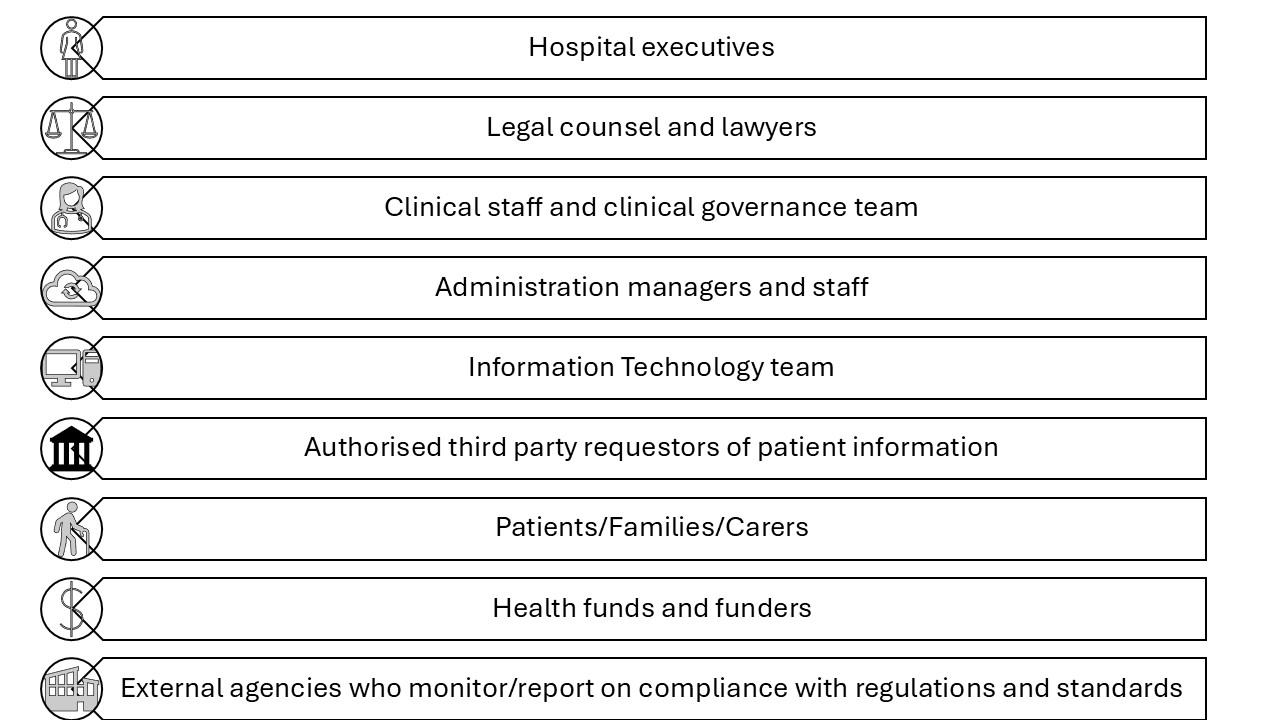

Key stakeholders of the HIS include hospital executives, legal counsel, clinical governance, clinical heads/leaders, clinical staff, the billing team, administration managers and staff, IT team, authorised third parties who receive patient data, patients, third party requestors of patient information, external agencies who monitor/report on compliance with regulations and standards, and health funds (private hospitals). These stakeholders play crucial roles in ensuring the effective management and use of health information within the system and are shown in the figure below.

Key Implications for Practice

HIS leaders have broad, discipline specific and contextual skills, knowledge, and experience. The following are key elements for effective practice to manage risk, people, diverse stakeholder groups, lead change, and the constantly evolving health and information management landscape:

- Effective Leadership: Authentic and ethical leadership are the mandate of modern leadership practice, requiring leaders to understand their purpose, practice solid values, establish connected relationships, and demonstrate self-discipline while demonstrating prudence, temperance, justice, and fortitude.

- Strategic Management: Leaders must understand the organisational context and drivers, set vision and direction, align operational performance with strategic goals, and ensure compliance with medico-legal and other requirements.

- Performance Management: Leaders must apply principles of performance management to demonstrate accountability, transparency, and commitment, celebrate success, and address areas for improvement.

- Financial Management: Leaders must steward organisational finances well, advocating for appropriate funding to service the needs of the organisation in the HIS functions, and contributing to organisational funding optimisation.

- Risk Management: Leaders must identify, assess, and mitigate risks associated with the management and use of information assets. This involves conducting risk assessments, developing strategies for minimising risks, and ensuring strong governance to control risks associated with data loss and the protection of staff and consumer privacy.

- Health Information Service Functions: Leaders need to oversee core functions of health information services, including health record management, compliance with medico-legal requirements and information privacy laws, clinical coding, maintaining high standards of data quality and reporting, and health information system management.

- People Management: Leaders in health information services need to manage teams effectively, including health information managers and clinical coders, leading workforce planning, managing intergenerational and diverse workforces, investing in training, education, professional development, and career development, and ensuring safe and healthy work environments.

- Stakeholder Management: Effective leadership in health information services requires collaboration with key stakeholders such as IT departments and other healthcare staff to ensure effective data management and health information system use and implementation.

These implications highlight the important combination of effective leader behaviour and expertise in health information management to effectively lead the health information service.

Activity – Test your knowledge

Test your knowledge with this short quiz on leading the health information system.

References

Abdelhak, M., & Hanken, M. A. (2016). Health information: management of a strategic resource (Fifth edition. ed.). Elsevier.

Adjekum, A., Blasimme, A., & Vayena, E. (2018). Elements of trust in digital health systems: scoping review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 20(12), e11254.

Almond, H., & Mather, C. (2023). Digital Health: A Transformative Approach. Elsevier Health Sciences.

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2024). 223933 Health Information Manager, OSCA – Occupation Standard Classification for Australia. https://www.abs.gov.au/

Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Healthcare. (2021). National Safety and Quality Health Service Standards. In (2nd ed.).

Australian Digital Health Agency. (2024). My Health Record. https://www.digitalhealth.gov.au/

My Health Record Act, (2012). https://www.legislation.gov.au/C2012A00063/latest/text

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2025). Health Workforce. Australian Government. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/workforce/health-workforce

IHACPA. (2025). Activity based funding. https://www.ihacpa.gov.au/health-care/pricing/national-efficient-price-determination/activity-based-funding

Barrow, J. M., & Annamaraju, P. (2025). Change Management In Health Care. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing Copyright © 2025, StatPearls Publishing LLC.

Ben‐Tovim, D. I., Dougherty, M. L., O’Connell, T. J., & McGrath, K. M. (2008). Patient journeys: the process of clinical redesign. Medical Journal of Australia, 188(S6), S14-S17.

Boris, V. (2021). Whoever They Are, Wherever They Are: Empowering Everyone You Lead. In: Leading the way Ideas and insights from Harvard Business Publishing Corporate Learning.

Braithwaite, J., Herkes, J., Ludlow, K., Testa, L., & Lamprell, G. (2017). Association between organisational and workplace cultures, and patient outcomes: systematic review. BMJ Open, 7(11), e017708. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017708

Briggs, D., & Isouard, G. (2015). Managing and leading staff. In G. E. Day & S. G. Leggat (Eds.), Leading and managing health services: An Australasian perspective. Cambridge University Press.

Brownie, S., & Holmes, A. (2015). Partnering with stakeholders. In G. E. Day & S. G. Leggat (Eds.), Leading and managing health services: An Australasian perspective. Cambridge University Press.

Chen, Y., VanderLaan, P. A., & Heher, Y. K. (2021). Using the model for improvement and plan‐do‐study‐act to effect smart change and advance quality. Cancer cytopathology, 129(1), 9-14.

Cole, C. (2024). How to Enhance Your Decision-Making Skills as a Leader. https://online.hbs.edu/blog/post/leadership-decision-making

Day, G. E., & Shannon, E. (2015). Leading and managing change. In G. E. Day & S. G. Leggat (Eds.), Leading and managing health services: An Australasian perspective. Cambridge University Press.

Dendere, R., Janda, M., & Sullivan, C. (2021). Are we doing it right? We need to evaluate the current approaches for implementation of digital health systems. Aust Health Rev, 45(6), 778-781. https://doi.org/10.1071/ah20289

Dols, J., Landrum, P., & Wieck, K. L. (2010). Leading and Managing an Intergenerational Workforce. Creative nursing, 16(2), 68-74. https://doi.org/10.1891/1078-4535.16.2.68

Domínguez, E., Pérez, B., Rubio, Á. L., & Zapata, M. A. (2019). A taxonomy for key performance indicators management. Computer Standards & Interfaces, 64, 24-40. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/j.csi.2018.12.001

Dweck, C., & Hogan, K. (2016). How Microsoft uses a growth mindset to develop leaders. Harvard Business Review, 1-4.

Edwards, I. (2015). Financial management. In G. E. Day & S. G. Leggat (Eds.), Leading and managing health services: An Australasian perspective. Cambridge University Press.

Edwards, J. (2024). Mastering Strategic Management. Pressbooks. https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/strategicmanagement/

Hanson, R. M. (2011). Good health information–an asset not a burden! Australian Health Review, 35(1), 9-13.

Hardy, L. R. (2024). Health informatics: An interprofessional approach (3rd ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences.

Harrison, R., Fischer, S., Walpola, R. L., Chauhan, A., Babalola, T., Mears, S., & Le-Dao, H. (2021). Where do models for change management, improvement and implementation meet? A systematic review of the applications of change management models in healthcare. Journal of healthcare leadership, 85-108.

Health Information and Management Systems Society. Change management. https://www.himss.org/

Health Information Management Association of Australia. (2024). Clinical Coding Practice Framework v 2.0. https://www.himaa.org.au/public/169/files/Website%20Document/Our%20Work/Framework/Oct24/Clinical%20Coding%20Practice%20Framework%20-%20October%202024.pdf

Health Information Management Association of Australia. (2025a). Health Information Management Professionals. https://www.himaa.org.au/about-himaa/about-himaa/

Health Information Management Association of Australia. (2025b). HIMAA Health Information Management Profession Identity Statement. https://www.himaa.org.au/public/169/files/Website%20Document/Our%20Work/Advocacy/HIMAA%20Health%20Information%20Management%20Profession%20Identity%20Statement%20v1_0.pdf

Health Information Management Association of Australia (HIMAA). (2023). Health Information Manager (HIM) Professional Competency Standards v 4.0. https://www.himaa.org.au/public/169/files/Website%20Document/Our%20Work/Competency%20Standards/HIM%20Professional%20Competency%20Standards%20v_4%202023.pdf

Hofmeyer, A., & Taylor, R. (2021). Strategies and resources for nurse leaders to use to lead with empathy and prudence so they understand and address sources of anxiety among nurses practising in the era of COVID-19. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 30(1-2), 298-305. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/jocn.15520

Hovenga, E., & Grain, H. (2023). Digital Health: A Transformative Approach. In H. Almond & C. Mather (Eds.). Elsevier Health Sciences.

Hovenga, E., & Lloyd, S. (2006). Managing health services : concepts and practice. In M. G. a. A. Harris (Ed.), (2nd ed.). Elsevier Australia.

Independent Health and Aged Care Pricing Authority. (2025). Classification overview. https://www.ihacpa.gov.au/health-care/classification/icd-10-amachiacs

International Standards Organisation. (2018). ISO 31000:2018, Risk management — Guidelines. In.

Jani, K., & Chaudhary, B. (2023). Importance of Hospital Management. In D. Bhatia, P. K. Chaudhari, B. Chaudhary, S. Sharma, & K. Dhingra (Eds.), A Guide to Hospital Administration and Planning (pp. 25-41). Springer Nature Singapore. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-19-6692-7_2

Jian, G. (2022). From empathic leader to empathic leadership practice: An extension to relational leadership theory. Human Relations, 75(5), 931-955. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726721998450

Kotter, J. (2021). The 8 Steps for Leading Change Kotter’s award-winning methodology is the proven approach to producing lasting change. Kotter Inc. https://www.kotterinc.com/methodology/8-steps/

Lloyd, S., & Craig, J. (2023). Digital health – health managers leading innovation in healthcare. In S. Lloyd, R. Olley, & E. Milligan (Eds.), Leading in Health and Social Care. Pressbooks. https://doi.org/10.25904/6A38-4917

Marc, D., Butler-Henderson, K., Dua, P., Lalani, K., & Fenton, S. (2019). Global Workforce Trends in Health Informatics & Information Management. Studies in health technology and informatics, 264, 1273-1277. https://doi.org/10.3233/SHTI190431

NEJM Catalyst. (2018). What Is Risk Management in Healthcare? https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.18.0197

NSW Health. (2025). Flexible Work Policy PD2025_005. https://www1.health.nsw.gov.au/pds/ActivePDSDocuments/PD2025_005.pdf

Olley, R. (2023a). Performance Management and Training and Development of the Health Workforce. In Leading in Health and Social Care. Pressbooks.

Olley, R. (2023b). Talent Management, Recruitment and Selection. In Leading in Health and Social Care. Pressbooks.

Olley, R. (2023c). The Theories of Leadership. In S. Lloyd, R. Olley, & E. Milligan (Eds.), Leading in Health and Social Care. Pressbooks. https://doi.org/10.25904/6A38-4917

Patterson, D., Cameron, E., Brutus, S., & Baronian, N. (2023). Human Resources Management. Pressbooks. https://pressbooks.atlanticoer-relatlantique.ca/humanresourcesmgmt/

Prosci. (n.d.). Prosci Adkar Methodology. https://www.prosci.com/methodology/adkar

PwC Australia. (2022). Proven precautions to help protect health organisations and patients from cyberattacks. https://www.pwc.com.au/health/health-matters/cyber-security-the-healthcare-sector.html

Radtke, L. (2024). Principles of Leadership & Management. Pressbooks. https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/leadershipandmanagement/

Sequeira, A. R., & Aish, K. (2023). Leading a Healthy Workforce. In Leading in Health and Social Care. Pressbooks.

Smallwood, R. F. (2018). Information Governance for Healthcare Professionals: A Practical Approach (First edition. ed.). Productivity Press. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203705247

Smith, C., Babich, C., & Lubrick, M. (2020a). Leadership and Management in Learning Organizations. Pressboks. https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/educationleadershipmanagement/

Smith, C., Babich, C., & Lubrick, M. (2020b). Leadership in the Workplace (H. Maye, Ed.). Pressbooks. https://spscc.pressbooks.pub/leadershipinofficeadministration/front-matter/cover/

Standards Australia. (2019a). Health records, Part 1: Paper health records. In. Australia: HE-025 (Health Records).

Standards Australia. (2019b). Health records, Part 2: Digitized health records. In. Australia: HE-025 (Health Records).

University of Minnesota. (2017). Chapter 15: Organizational Culture. In Pressbooks (Ed.), Organizational Behavior. https://ecampusontario.pressbooks.pub/orgbehavior/part/chapter-15-organizational-culture/

Williams, G., & Archdall, B. (2015). Workforce planning. In G. E. Day & S. G. Leggat (Eds.), Leading and managing health services: An Australasian perspective. Cambridge University Press.

Wu, J., Elliott O’Dare, C., & Greene, J. (2025). Ageism and Intergenerational Dynamics in the Workplace: A Scoping Review with Implications for Gender and Sustainable Human Resource Management (HRM). Gender and Sustainability in the Global South. https://doi.org/10.1515/gsgs-2024-0010

Image descriptions

Figure 2: Five concentric circles represent the dimensions of authentic leadership, moving outward from the core:

- Foundation of Self-Awareness – Knowing and being true to oneself, developing self-efficacy, and maintaining a positive self-concept.

- Genuine Relationships – Leaders build genuine, open, and transparent relationships with the people around them.

- Conviction of Values – Leaders are deeply aware of their values, are trustworthy, reliable, unbiased in decision-making, and encourage growth in others.

- Service for Others – Leaders prioritise others’ needs, demonstrating a service mindset that focuses on “we” over “I.”

- Vision – Leaders create a compelling vision for the future, inspiring purpose for themselves and those they lead.

The layout emphasises that self-awareness is the foundation, and each outer layer builds upon the previous to create effective, authentic leadership.

A table depicting a simple risk management plan for the introduction of an information system. The table is divided into three rows, each with three columns labeled “Risk”, “Impact” and “Strategy to manage”.

- The first row uses unavailable nursing staff for training as an example of “Risk” and identifies the level of “Impact” as high. The strategy to manage this risk is develop a training program in consultation with nurse unit managers.

- The second row uses the delay of hardware and software installation as an example of “Risk” and identifies the level of “Impact” as high. The strategy to manage this risk is work with vendors closely and align contractual requirements to health service needs.

- The third row uses insufficient funding to complete project objectives as an example of “Risk” and identifies the level of “Impact” as low. The strategy to manage this risk is monitor the agreed upon budget for project.

Figure 4: A horizontal process diagram illustrating steps in clinical process service redesign. At the top, a text box states:

“Clinical, workplace, administrative challenge or model of care that requires improvement to improve staff or consumer experience.”

Below, five connected right-facing arrows represent sequential phases:

- Diagnosis phase – identifying the problem or area needing improvement.

- Solutions generation phase – brainstorming and developing potential interventions.

- Implementation planning – outlining resources, timelines, and responsibilities for action.

- Solution implementation and monitoring – executing the plan and tracking progress.