Healthcare Classification and Terminologies

Vickie Bennett; Filippa Pretty; and Brooke McPherson

Learning Outcomes

In this chapter you will gain knowledge of:

- Classifications and terminologies and how to derive value from data for both.

- How classifications impact funding models in Australia.

- Mappings, what they are and what they are used for.

- Considerations when choosing and implementing a classification or terminology.

- Understand the World Health Organization’s (WHO) Family of International Classifications.

We will also delve into the many uses of classifications – locally, nationally, and internationally.

Introduction

Healthcare classifications and terminologies serve as fundamental tools in health information management, providing standardised frameworks for organising and analysing healthcare data. The World Health Organization’s Family of International Classifications (WHO-FIC), which includes the International Classification of Diseases (ICD), is foundational for global health data standardisation. In Australia, these classifications directly impact healthcare funding through systems like Activity Based Funding (ABF), where clinical coding using ICD-10-AM. a derivative of the ICD, is used to group cases into clinically meaningful and resource homogenous groups and is used for the allocation of funding for healthcare services. Mappings play a crucial role in this ecosystem by creating relationships between different classification systems and terminologies, enabling data interoperability and comparison across various healthcare settings and systems. The effective use of these classification, terminology and grouping systems allows healthcare organisations to derive insights from their data, supporting clinical decision-making, research, epidemiological studies, and health policy development while ensuring consistent communication across the healthcare continuum. In this chapter we explore health classifications, terminologies, the ICD family of classifications and important issues relating to the use and application of these systems.

What are Health Classifications and Terminologies?

Health Classifications

Health classifications are a system of categories to which morbid or interventional entities are assigned according to established criteria (WHO [PDF]). They organise large quantities of clinical and other detailed information on diseases, related health conditions, and other concepts (such as drugs and external causes of injury) into meaningful categories (WHO [PDF]). These categories are hierarchical (e.g. acute through to chronic, mild to severe), exhaustive, and mutually exclusive. Health classifications usually have an index that assists a user to the correct code assignment, which can also be determined using rules and standards. Health classifications are used for statistical reporting, epidemiology, auditing, planning, financial billing, and other use cases where comparable data are required (WHO [PDF]). The most well-known and widely used health classification is the World Health Organization’s (WHO) International Classification of Diseases (ICD). This classification system, or adaptations is used widely across the globe to collect statistical and other data about patients and populations.

Clinical Terminologies

A terminology is a structured vocabulary of terms and concepts arranged according to relationships and definitions that provide context. A clinical terminology uses medical vocabulary to describe and capture diseases, interventions, clinical findings, treatments, and medicines (National Library of Medicine, n.d.). It enables comprehensive and detailed capture of care and treatment provided during clinical care (Australian Digital Health Agency, 2020; Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation, 2023). Terminology tools systematically codify clinical information entered into an electronic health record, and allow for standardised information exchange between clinicians, thus facilitating patient care across multiple healthcare providers (Australian Digital Health Agency).

Why Are They Important?

With increased investments into digital systems and changes in the delivery of clinical practice towards more integrated and person-centred care, the adoption of standardised classifications and terminologies is critical for establishing clarity and consistency when encoding, documenting, and exchanging information on health-related events (Pretty et al., 2023).

Classifications and terminologies provide a common language to describe the care and treatment of patients using standardised terms (Harrison, 2021; CSIRO, 2024). The use of fit-for-purpose and freely available classifications and terminologies is important for representing information in a consistent manner, enabling the storage, retrieval, and meaningful analysis of health information and exchange of information between clinicians (Harrison et al., 2021).

Using clinical terminologies and classifications together for their intended primary purposes (clinical inputs and communication, and statistical outputs and reporting, respectively), enhances and strengthens clinical and patient information use, decision-making, and outcomes (Harrison, 2021).

What Health Classifications and Terminologies are Used Internationally and in Australia?

International Classifications

The WHO develops and maintains a ‘family’ of classifications that capture and describe the health spectrum (WHO, n.d.). They are:

- the International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD)

- the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF)

- the International Classification of Health Interventions (ICHI) (WHO, n.d.).

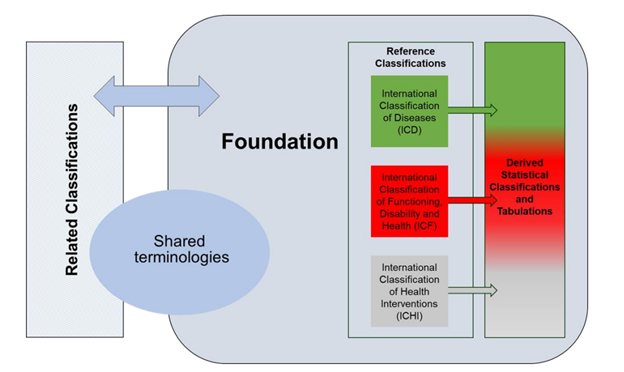

The WHO Family of International Classifications (WHO-FIC) aims to provide a conceptual framework of information dimensions related to health and health management. They establish a common language to improve communication and permit comparisons of data across countries’ health-care disciplines, services, and time (see Figure 1).

The WHO-FIC Reference Classifications have a core structure called the foundation, which is a multidimensional collection of all health entities, including diseases, injuries, external causes, anatomy, medications, functioning and disability concepts, as well as health interventions. The classifications are drawn from this foundation, known as linearisations (what were previously known as tabular lists) (Fung et al, 2020, Fung et al, 2023). Foundation entities may be included in a linearisation as a code, category or searchable (index) term (Fung et al, 2020, Fung et al 2023). Each entity in the foundation has a unique identifier, called a uniform resource identifier (URI) or “foundation URI”. This URI enables the same entity to be linked across the reference classifications to identify the same concept even if the classifications gives it a different code in each different classification system (Fung et al, 2020, Fung et al, 2023). The URI can also be used to track data entry at point of care to understand what terminology is in current use to ensure the terms are searchable entities (i.e., index terms) (WHO, n.d.).

International Classification of Diseases

The International Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems (ICD) is the WHO classification for recording, reporting, and grouping conditions and factors that influence health. It contains categories for diseases and disorders, health related conditions, external causes of disease or death, anatomy, sites, activities, medicines, vaccines, and more. The ICD facilitates systematic recording, analysis, interpretation and comparison of mortality and morbidity data and has been the basis for comparable statistics within countries and internationally over time (Harrison et al, 2021).

The latest version, the 11th Revision (ICD-11), was endorsed in 2019 and came into effect in 2022 for potential implementations across multiple use cases.

Activity

Watch this video, by the WHO that introduces ICD-11 and note key changes.

ICD-11 uses an ontology-based design. This ontology-based design of ICD-11 and the migration of its sibling classifications (ICF and ICHI) into the same ontological infrastructure has enabled the full integration of terminology and classification in a common platform (World Health Organization, 2021).

ICD-11 has been designed to enable semantic interoperability of individual data, reusability of recorded data for use cases other than health statistics, including decision support, resource allocation, reimbursement, guidelines, and more (World Health Organization, 2021).

The ICD-11 contains up-to-date scientific knowledge and mechanisms that allow for health information to be used in:

- the improvement of health outcomes;

- patient safety and quality analysis;

- meaningful population health reporting;

- integrated care; and

- strategic planning and delivery of health care services (WHO, 2021).

The ICD-11 has a Reference Guide [opens in new tab] that provides comprehensive detail, including historical background material, instructions, and guidelines for use. ICD chapters have been revised for ICD-11. There are now 26 chapters and two supplementary sections in the classification. Chapters/sections not previously in the ICD-10 include:

- Chapter 04 Diseases of the immune system (previously in Chapter 03)

- Chapter 07 Sleep-wake disorders

- Chapter 17 Conditions related to sexual health

- Chapter 26 Supplementary chapter Traditional Medicine Conditions

- Section V Supplementary section for functioning assessment

- Section X Extension codes (World Health Organization, 2021)

International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health

The International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health is the WHO classification for measuring health and disability at individual and population levels. It also includes environmental factors (World Health Organization, 2001). ICF was endorsed as the international standard to describe and measure health and disability in 2001 (World Health Organization, 2001).

The ICF was developed to provide a scientific basis and common language for describing health and health-related states, to facilitate communication between different users, such as health care workers, policy makers, quality assurance evaluators, and the public, including people with disabilities, about health and health related states, outcomes and determinants in both positive and negative terms (World Health Organization, 2001).

The ICF has two parts:

- Part One – functioning and disability, which captures body functions and structures, and activities and participation

- Part Two – contextual environmental and personal factors (World Health Organization, 2001).

The ICF can be used as:

- A statistical tool – in the collection and recording of data via population studies or in an information management system

- A research tool – to measure outcomes, quality of life, or environmental factors

- A clinical tool – in needs assessments, vocational assessments, or rehabilitation and outcome evaluations (World Health Organization, 2001).

As the ICF is a health and health-related classification, it is also used internationally in other sectors, such as insurance, social security, labour, education, social policy, and environmental modification (World Health Organization, 2001). It can be used in conjunction with the ICD to provide information on diagnoses as well as functioning capacity to give a broader and more meaningful picture of the health of people or populations. It can also be used in conjunction with the ICHI to provide information on interventions undertaken for assessment and management/treatment of functioning and disabilities, and the outcomes (World Health Organization, 2001).

International Classification of Health Interventions

The ICHI is a newly developed WHO classification for reporting and analysing health interventions for clinical and statistical purposes (World Health Organization, 2025c). A health intervention is defined as “an act performed for, with or on behalf of a person on a population whose purpose is to assess, improve, maintain, promote or modify health, functioning or health conditions” (World Health Organization, 2025c). Examples of health interventions include surgical procedures and public health interventions such as immunisation.

Historically, the International Classification of Procedures in Medicine was published by WHO in 1976 and included diagnostic, medical, and surgical interventions (Gersenovic, 1995 cited in Fung et al, 2022). While the 10th Revision of ICD was being developed, the Heads of WHO Collaborating Centres for Classification of Diseases “recognized that the process of consultation that had to be followed before finalization and publication was inappropriate in such a wide and rapidly advancing field”. Therefore, it was decided that there should be no revision of the International Classification of Procedures in Medicine for ICD-10 (Fung et al, 2022).

However, over time, comparisons of hospital interventions across Member States could not be undertaken due to the large number of interventions classifications used across Member State countries. As a as result, from 2007, the ICHI has been developed by a wide range of people drawn from WHO-FIC Collaborating Centres in all WHO regions, as well as a number of WHO staff (World Health Organization, 2025c). The ICHI includes a broad range of interventions performed in medical, surgical, mental health, primary care, allied health, functioning, rehabilitation, and health promotion, as well as interventions used in community and public health. It does not include information about the provider of an intervention or the setting. The reasons for and outcomes of the intervention are also not included; these can be captured using the ICD and/or ICF (World Health Organization, 2025c). The ICHI is grouped into the following four sections:

- Interventions on Body Systems and Functions

- Interventions on Activities and Participation Domains

- Interventions on the Environment

- Interventions on Health-related Behaviours (World Health Organization, 2025c).

Health Classifications Used in Australia

In Australia, the Australian Bureau of Statistics (2025) classifies cause of death using the ICD-10 via an automated coding system known as Iris. The coded data generated are compiled in the National Mortality dataset and then used for statistical reporting as well as mandatory reporting to WHO (Australian Bureau of Statistics, 2025). For morbidity, the Independent Health and Aged Care Pricing Authority reviews and updates existing classifications and is also responsible for introducing new classifications for health service categories without an existing classification. Overtime, new classifications have been created, for example to better describe sub and non-acute care patients who are treated in Australian hospitals. Table 1 below shows the classifications used across each of the patient service categories. For further information on each classification please open the hyperlinks.

Note: Each link opens in a new tab.

| Service category | Classification |

|---|---|

| Admitted care | International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision, Australian Modification (ICD-10-AM), Australian Classification of Health Interventions (ACHI), Australian Coding Standards (ACS) |

| Admitted acute care | Australian Refined Diagnosis Related Groups classification (AR-DRGs) |

| Subacute and non-acute care | Australian National Subacute and Non-Acute Patient classification (AN-SNAP) |

| Emergency care | Emergency Care ICD-10-AM Principal Diagnosis Short List (EPD Short List)

Australian Emergency Care Classification (AECC) Urgency Disposition Groups (UDG) |

| Non-admitted care | Tier 2 Non-Admitted Services Classification (Tier 2) |

| Mental health care | Australian Mental Health Care Classification (AMHCC) |

| Teaching, training and research | Australian Teaching and Training Classification (ATTC) |

International Terminologies

Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine Clinical Terms (SNOMED CT) is a comprehensive, multilingual clinical healthcare terminology with scientifically validated clinical content enabling consistent representation of clinical content in electronic health records (SNOMED International, 2025). SNOMED CT contains concepts for diagnosis, clinical findings like signs and symptoms, surgical, therapeutic and diagnostic procedures as well as observables (for example heart rate), and concepts representing body structures, organisms, substances, pharmaceutical products, physical objects, physical forces, specimens and many other types of information that may need to be recorded (SNOMED International, 2025). Every concept represents a unique clinical meaning, referenced using a unique, numeric and machine-readable identifier. The identifier provides a unique reference to each concept and does not have any human interpretable meaning (SNOMED International, 2025). Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Codes (LOINC, 2025) is a terminology developed in 1994 for laboratory and clinical observations to send clinical data electronically from laboratories and other data producers to hospitals, clinicians offices, and payers who use the data for clinical care and management purposes. It contains a rich catalogue of measurements, including laboratory tests, clinical measures like vital signs and anthropometric measures, standardized survey instruments, and more. LOINC also contains codes for collections of these items, such as panels, forms, and documents (LOINC, 2025). International terminologies such as SNOMED CT and LOINC are also used in the Australian context.

Activity

Watch this short video on SNOMED CT and consider why it is an important foundational terminology.

Other Terminologies

Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities [opens in new tab] is an international medical terminology with an emphasis on use for data entry, retrieval, analysis, and display. It applies to all phases of drug development, and to the health effects and malfunction of devices. An appendix includes concept descriptions which describe how a medical concept is interpreted, used, and classified. The concept descriptions are intended to aid the consistent and accurate use of Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities in structured capture, retrieval, and analysis. This Dictionary is used by Australia’s Therapeutic Goods Administration [opens in new tab]. The Mondo Disease Ontology [opens in new tab] aims to harmonise disease definitions across the world. It is a semi-automatically constructed ontology that merges in multiple disease resources to yield a coherent merged ontology (Mondo, n.d).

Australian Terminologies

SNOMED CT Australian Release (SNOMED CT-AU) is the Australian extension to SNOMED CT created under licence with SNOMED International (CSIRO, 2025). SNOMED CT-AU provides local variations and customisation of terms relevant to the Australian healthcare system. It includes the international resources along with all Australian developed terminology, including the Australian Medicines Terminology for use in Australian clinical IT systems (Australian Digital Health Agency, 2025b). The Australian Government has identified SNOMED CT-AU as the preferred national terminology for Australia, and this has been endorsed by all Australian state and territory governments (CSIRO, 2025).

The National Clinical Terminology Service is critical to support of SNOMED CT-AU [opens in new tab]. SNOMED CT-AU has been available for use in Australia since 1 July 2006 and is updated monthly. Australia’s National Clinical Terminology Service was launched in 2016 and is underpinned by the CSIRO’s Ontoserver Fast Healthcare Interoperability Resources Terminology server which is hosted on behalf of the Australian Digital Health Agency. Ontoserver licences are available for free for end use in Australia from the Australian Digital Health Agency [opens in new tab]. Since it launched, the National Clinical Terminology Service has facilitated standard terminologies in Australia’s digital health systems and enabled standard-based interoperability in data exchange (CSIRO, 2025).

LOINC terms are also used in Australia, particularly in pathology systems, and a subset of LOINC terms are now also included in the NCTS (Australian Digital Health Agency, 2025).

Implementing Classification or Terminology-based Systems

When a new data collection is required, several items should be considered before selecting a classification or terminology. For example, if you want very detailed information for research purposes the ICD may be sufficient, for clinical care a more granular system may be required, such as SNOMED CT.

What is the Purpose of the Data Collection?

The use case should determine which classification or terminology would be most appropriate to use, so this must be carefully considered. For example, the ICD would not be used in a data collection about interventions; a classification for interventions would be more suitable, such as ICHI or ACHI or a terminology that contains interventional concepts.

What Outputs Would be Required?

The following questions are useful to consider:

-

- What type and level of data aggregation do you intend this data collection to produce?

- What type of reporting do you intend to produce?

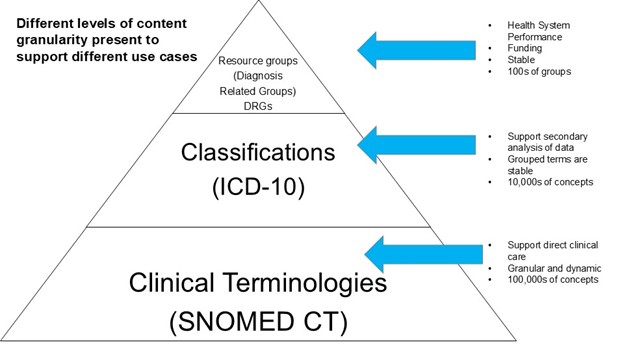

Figure 2 demonstrates the granularity required for specific use cases.

Source: Adapted from Slide 9 in Australian Digital Health Agency (2020). [Go to image description]

Uses of Classification Data – Local, National and International

Coded data, abstracted from health records can have many uses across all levels of healthcare. This includes turning coded data into other forms through classification systems. Examples of uses include:

- Casemix, DRGs – provide information for the assignment of patients into the appropriate diagnosis related group to be used for the funding of the hospital.

- Research – having diseases and interventions with allocated codes enables an easy way to sort, retrieve, and review data for clinical research.

- National and jurisdictional level statistics – enables stakeholders to monitor health information at population levels, to influence policy direction, public health planning, and funding.

- Health service planning and evaluation – an institution or an area health service can use the data to assess the uses of their facilities and allocate funding and equipment.

- Quality assurance activities –people can use coded data to examine the outcome of diseases and interventions and assess quality of coding and analyse clinical indicators. See the chapter on Patient Safety and Sustainable Development Goals Through the Lens of Health Information Management .

- Epidemiology – coded data are used to both track and project disease patterns and frequency of the population.

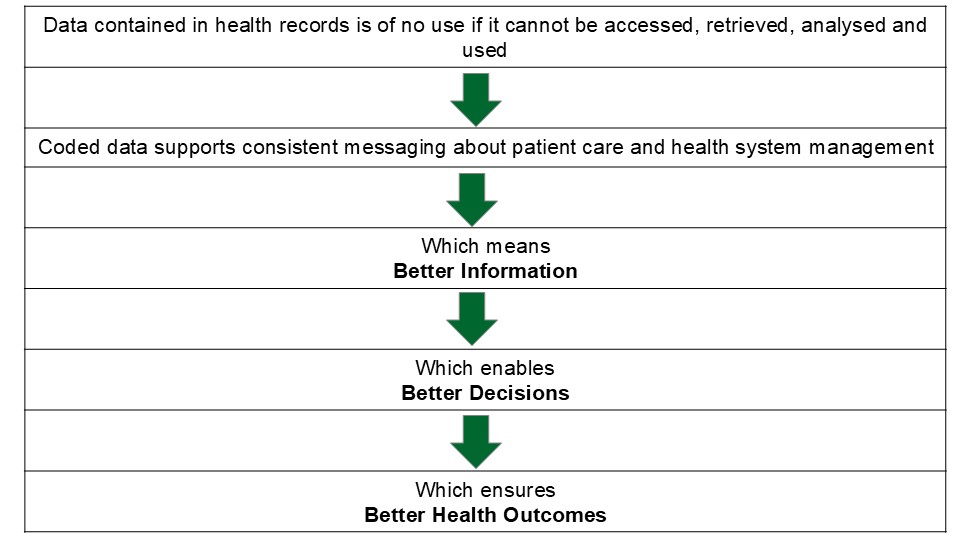

Figure 3 provides an overview of the value of health care data capture, transfer, and use.

The Path of Admitted Care Morbidity Data – Local, National and International

The most common coded data in Australia are morbidity data collected for hospital admitted patients. These data are generated by health information managers and clinical coders in every hospital in Australia, who code each separation of admitted patients using ICD-10-AM/ACHI/ACS (2025b). Hospitals submit coded data to their respective state or territory health department, usually after the end of a specific reporting period (often monthly). These data then undergo rigorous quality assurance at the jurisdictional level, and hospitals can address data issues before the data collection closes each year. State and territory health departments then forward on their data to repositories held at the national level. The frequency for this can vary depending on which repository the data are being submitted to.

One repository is the National Hospitals Data Collection [opens in new tab], held by the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). Data are submitted to this repository on an annual basis. This repository encompasses the major national hospital databases including the National Hospital Morbidity Database and the National Non-Admitted Patient Emergency Department Care Database.

These data are then used for health statistics reporting via publications such as:

- Australia’s health [opens in new tab]: a biannual publication outlining health information about the Australian population

- MyHospitals [opens in new tab]: containing hospital level information on admissions, presentations to emergency departments and waiting times for elective surgery.

- Health and Wellbeing of First Nations people [opens in new tab]

- Australian Burden of Disease Study [opens in new tab]

The morbidity data is also available to download from:

Australia has an obligation to supply health and health-related data to the WHO, who then publish this data in the WHO Global Health Observatory [opens in new tab] and the AIHW is often involved in the data supply. Australia benefits from this in that it allows for international comparisons of health, which helps to identify opportunities for preventative action and health system improvement (AIHW, 2025).

Australia also provides coded morbidity data to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), which is published in an online database, OECD Health Statistics (AIHW, 2025). This is the most comprehensive source of comparable statistics on health and health systems across OECD and partner countries. The database contains information on health status, health care services and health care spending for member countries. Information from OECD Health Statistics facilitates international comparative reporting, supports policy planning and decision making, and enables health-related research and analysis.

Mappings

With the increasing adoption of electronic health records, the amount of coded data being collected is increasing exponentially. Today these data are encoded in a multitude of health care classifications and terminologies for different purposes. Classification and terminology mapping are used to transform such data so that they can be used for additional purposes, aggregated with data from other sources, or exchanged between systems (World Health Organization, 2024a).

Another reason for terminology mapping is the dynamic nature of health care. As scientific understanding of disease processes improves and new interventions become available, classifications and terminologies need to evolve. During a mapping process, the differences in the intended purpose (use case), structure, and constraints of the different classifications and terminologies may mean that maps between them may be approximate and dependent on the subjective judgement of map developers and users. Limitations in the development of maps may also mean that transformation of data based on these maps may involve information loss. Whether such information loss is acceptable or can be mitigated depends on the intended usage of the data. For example, where a category’s specificity is reduced it may affect the ability to report on individual conditions.

Classification and Funding

Activity based funding (ABF) in the Australian healthcare sector is the way of funding hospitals based on the number and mix of patients they treat. If a hospital treats more patients, it may receive more funding. ABF also takes into account that some patients are more complicated to treat than others. for example a hospital episode of care for a simple appendicectomy is less complicated and less costly than an episode of care for an organ transplant (Independent Health and Aged Care Pricing Authority, 2025b). The Australian Refined Diagnosis Related Groups (AR-DRG) classification provides a clinically meaningful way to relate or group the number and type of patients treated in admitted acute episodes of care to the resources required in treatment (Independent Health and Aged Care Pricing Authority, 2023e).

ABF should support timely access to quality health services, improve the value of the public investment in hospital care and ensure a sustainable and efficient network of public hospital services. ABF payments should be fair and equitable, including being based on the same price for the same service across public, private or not for profit providers of public hospital services (Independent Health and Aged Care Pricing Authority, 2025b).

The Pricing Framework for Australian Public Hospital Services [opens in new tab] is used to allocate funding and is updated annually. It outlines the principles, scope and methodology adopted by Independent Health and Aged Care Pricing Authority to determine the national efficient price and the national efficient cost for Australian public hospital services for the specific financial year (Independent Health and Aged Care Pricing Authority, 2025b).

How Does it All Work?

ICD-10-AM and ACHI codes are an integral part of the Australian Refined Diagnosis Related Groups (AR-DRGs) (Independent Health and Aged Care Pricing Authority, 2023e).

“The Australian Refined Diagnosis Related Groups (AR-DRG) classification provides a clinically meaningful way to group together treatments and services provided for admitted acute episodes of care to enable hospitals to be funded for these services using activity based funding” (Independent Health and Aged Care Pricing Authority)

To assign an AR-DRGs each episode is ‘grouped’ into clinically homogeneous groups – thereby reflecting resources required (usually by specialty) and complexity. Grouping logic is very complex, this is commonly performed by software programs, and only one AR-DRG is produced for each admitted patient episode of care (Independent Health and Aged Care Pricing Authority, 2023e).

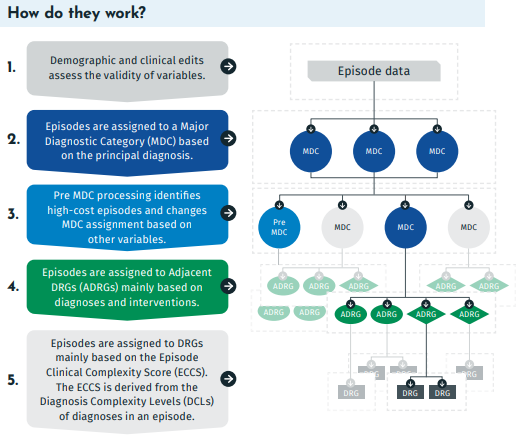

Figure 4 demonstrates AR-DRG assignment flow.

What Does an AR-DRG Look Like?

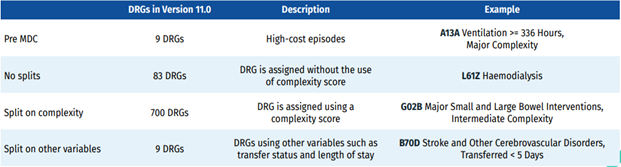

The AR-DRG classification was developed using a hierarchy of structures with various types of DRGs. There are special DRGs to cater for high cost episodes of care for example patients who have been on extended ventilation for long periods. There are DRGs where there is no splits, or further differentiation based on complexity. The vast majority of DRGs have splits to cater for complexity and also where other variables, such as transfer status and length of stay are used to categories episodes of care.

Terms Associated with AR-DRGS

In this section, major terms associated with Australian DRGs are explained. There is an abundance of material on the AR-DRGs [opens in new tab].

Major Diagnostic Category (MDC) – a split of cases based on the principal diagnosis. They correspond generally to the major organ systems of the body (AIHW, 2024a).

Table 2 demonstrates the number, names of MDCs for AR-DRGS (ADRGS), and the code that those DRGs begin with e.g., the letter A, B, C, etc. This helps users when examining a DRG. For example, if it commences with the letter B, the condition will belong to a disease and disorder of the nervous system.

| MDC | MDC Description | AR-DRG beginning with |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-MDC | Major procedures where the principal diagnosis may be associated with any MDC | A |

| 01. | Diseases and disorders of the nervous system | B |

| 02. | Diseases and disorders of the eye | C |

| 03. | Diseases and disorders of the ear, nose, mouth and throat | D |

| 04. | Diseases and disorders of the respiratory system | E |

| 05. | Diseases and disorders of the circulatory system | F |

| 06. | Diseases and disorders of the digestive system | G |

| 07. | Diseases and disorders of the hepatobiliary system and pancreas | H |

| 08. | Diseases and disorders of the musculoskeletal system and connective tissue | I |

| 09. | Diseases and disorders of the skin, subcutaneous tissue and breast | J |

| 10. | Endocrine, nutritional and metabolic diseases and disorders | K |

| 11. | Diseases and disorders of the kidney and urinary tract | L |

| 12. | Diseases and disorders of the male reproductive system | M |

| 13. | Diseases and disorders of the female reproductive system | N |

| 14. | Pregnancy, childbirth and the puerperium | O |

| 15. | Newborns and other neonates | P |

| 16. | Diseases and disorders of the blood and blood forming organs and immunological disorders | Q |

| 17. | Neoplastic disorders (haematological and solid neoplasms) | R |

| 18. | Infectious and parasitic diseases | T |

| 19. | Mental diseases and disorders | U |

| 20. | Alcohol/drug use and alcohol/drug induced organic mental disorders | V |

| 21A. | Injuries, Poisoning and Toxic Effects of Drugs: Multiple Trauma | W |

| 21B. | Injuries, Poisoning and Toxic Effects of Drugs | X |

| 22. | Burns | Y |

| 23. | Factors influencing health status and other contacts with health services | Z |

| GIs unrelated to principal diagnosis | General interventions unrelated to principal diagnosis | 8 |

| Error-DRGs | Error DRGs | 9 |

Pre MDC processing – Episodes are assessed as to whether they meet pre MDC criteria that identifies very high-cost episodes and is driven by a specific intervention code that overrides the outcome of the principal diagnosis-based MDC assignment (Independent Health and Aged Care Pricing Authority, 2023f).

Adjacent DRGs (ADRG) – Episodes are assigned to an ADRG mostly according to diagnosis and intervention codes. All MDCs have a hierarchical structure that separates the ADRGs into either the intervention or medical partition (Independent Health and Aged Care Pricing Authority, 2023f).

Partitions – These partitions divide the ADRG to represent the broad category of service:

For AR-DRG version 9.0 onwards these are:

- Intervention: separations involving a general intervention (operating room procedure) or at least one specific intervention (non-operating room procedure) significant to the MDC.

- Medical: separations not involving an operating room procedure or a locally significant non-operating room procedure. (Independent Health and Aged Care Pricing Authority, 2023f).

The Episode Clinical Complexity (ECC) Model was introduced in AR-DRG Version 8.0 and uses ICD-10-AM codes to determine the clinical complexity of an episode (Independent Health and Aged Care Pricing Authority, 2023f).The ECC model assigns an Episode Clinical Complexity Score to each episode that quantifies relative levels of resource utilisation within each ADRG and is used to split ADRGs into different DRG levels based on resource homogeneity.

The process of deriving an Episode Clinical Complexity Score for each episode begins by assigning a Diagnosis Complexity Level (DCL) value to each diagnosis reported for the episode. DCLs are integers that quantify the levels of resource utilisation associated with each diagnosis, relative to levels within the ADRG to which the episode belongs. DCL values are assigned to principal diagnosis and additional diagnosis codes and range between zero and five (Independent Health and Aged Care Pricing Authority, 2023f).

AR-DRG – the final DRG assigned when the ECC Model is applied based on the assigned ICD-10-AM codes for the episode of care (Independent Health and Aged Care Pricing Authority, 2023f).

Note: the demographic and clinical edits undertaken at the start of DRG allocation (see Figure 4) include age, sex, separation mode, length of stay, newborn admission weight, hours of mechanical ventilation, and same-day status. The edits also validate all diagnosis (ICD-10-AM) and intervention (ACHI) codes, combined with a patient’s age and sex. (Independent Health and Aged Care Pricing Authority, 2023f)

Potential issues in relation to the validity of the data may result in assignment to one of the three error DRGs:

- 960Z Ungroupable

- 961Z Unacceptable Principal Diagnosis

- 963Z Neonatal Diagnosis Not Consistent with Age/Weight.

AR-DRG data can be explored using the AIHW’s data cubes [opens in new tab].

Key Implications for Practice

- Health Information Managers (HIMs) must ensure robust coding practices using standardised classifications (e.g., ICD-10-AM) as this directly impacts healthcare funding through Activity Based Funding and DRG assignment.

- Healthcare organisations need to implement effective data quality assurance processes at local levels before submission to jurisdictional and national bodies to maintain data integrity and accuracy.

- HIM professionals should maintain expertise in multiple classification and terminology systems to support various use cases (e.g., clinical care, research, statistics) and enable data interoperability.

- HIM professionals need to understand and adapt to evolving classification systems (like ICD-11) to ensure organisational readiness for future transitions.

- Regular monitoring and analysis of coded data is essential for supporting quality assurance, research, epidemiology, and health service planning activities.

References

Australian Bureau of Statistics. (2025). Causes of Death, Australia methodology. https://www.abs.gov.au/methodologies/causes-death-australia-methodology/2023#classificationscs

Australian Digital Health Agency. (2020). Terminologies and classifications: SNOMED CT-AU and ICD-10-AM use in Australia. https://www.healthterminologies.gov.au/library/DH_3113_2020_TerminologyAndClassificationPresentation_v2.0.pdf

Australian Digital Health Agency. (2025a). 5-standards-for-systems-and-technologies. https://www.digitalhealth.gov.au/healthcare-providers/initiatives-and-programs/digital-health-standards/digital-health-standards-guidelines/get-started/5-standards-for-systems-and-technologies/clinical-coding-system#:~:text=Definition:,statistical%20analysis%20in%20healthcare%20settings

Australian Digital Health Agency. (2025b) Understanding clinical terminologyhttps://www.healthterminologies.gov.au/understanding-clinical-terminology-landing/

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). (2024a). Australian refined diagnosis-related groups (AR-DRG) data cubes. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/hospitals/ar-drg-data-cubes/contents/user-guide

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). (2024b). National Hospitals Data Collection. https://www.aihw.gov.au/about-our-data/our-data-collections/national-hospitals-data-collection

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW). (2025). Our international role. https://www.aihw.gov.au/about-us/international-collaboration

Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO). (2023). Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine-Clinical Terms (AU). https://vocabs.ardc.edu.au/viewById/18

Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO). (2024). Transforming healthcare with the National Clinical Terminology Service. https://aehrc.csiro.au/transforming-healthcare-with-the-national-clinical-terminology-service/

Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO). (2025). Clinical terminology tools. https://www.csiro.au/en/about/Corporate-governance/Ensuring-our-impact/Impact-case-studies/Future-Industries/Clinical-Terminology-Tools#:~:text=The%20results%20Making%20patient%20information%20more%20accurate,of%20a%20standard%20and%20contemporary%20clinical%20terminology.

Fung, K. W., Xu, J., Ameye, F., Burelle, L., & MacNeil, J. (2022). Evaluation of the International Classification of Health Interventions (ICHI) in the coding of common surgical procedures. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 29(1), 43-51.

Fung, K. W., Xu, J., & Bodenreider, O. (2020). The new International Classification of Diseases 11th edition: a comparative analysis with ICD-10 and ICD-10-CM. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 27(5), 738-746.

Fung, K. W., Xu, J., McConnell-Lamptey, S., Pickett, D., & Bodenreider, O. (2023). A practical strategy to use the ICD-11 for morbidity coding in the United States without a clinical modification. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 30(10), 1614-1621.

Harrison, J. E., Weber, S., Jakob, R., & Chute, C. G. (2021). ICD-11: an international classification of diseases for the twenty-first century. BMC medical informatics and decision making, 21(Suppl 6), 206.

Independent Health and Aged Care Pricing Authority. (2025a). Classification overview. https://www.ihacpa.gov.au/health-care/classification/classification-overview

Independent Health and Aged Care Pricing Authority. (2025b). Activity based funding. https://www.ihacpa.gov.au/health-care/pricing/national-efficient-price-determination/activity-based-funding

Independent Health and Aged Care Pricing Authority. (2025c). Pricing Framework for Australian Public Hospital Services. https://www.ihacpa.gov.au/health-care/pricing/pricing-framework-australian-public-hospital-services

Independent Health and Aged Care Pricing Authority. (2025d). Admitted acute care. https://www.ihacpa.gov.au/health-care/classification/admitted-acute-care

Independent Health and Aged Care Pricing Authority. (2023e). Australian Refined Diagnosis Related Groups overview and Version 11.0 development. https://www.ihacpa.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023-03/ar-drg_overview_and_version_11.0_development.pdf

Independent Health and Aged Care Pricing Authority. (2023f). Australian Refined Diagnosis Related Groups Version 11.0 Final Report. https://www.ihacpa.gov.au/sites/default/files/2022-08/ar-drg_v11.0_final_report.pdf

Independent Health and Aged Care Pricing Authority. (2023g) Australian Refined Diagnosis Related Groups Version 11.0 Fact Sheet https://www.ihacpa.gov.au/sites/default/files/2023-03/ar-drg_overview_and_version_11.0_development.pdf

Logical Observation Identifiers Names and Codes (LOINC). (2025). About LOINC. https://loinc.org/about/

Mondo (n.d.), Mondo Disease Ontology https://mondo.monarchinitiative.org/#about

National Library of Medicine (n.d.) Health Data Standards and Terminologies https://www.nlm.nih.gov/oet/ed/healthdatastandards/index.html

Ontotext. (2025). What Are Ontologies?. https://www.ontotext.com/knowledgehub/fundamentals/what-are-ontologies/

Palojoki , Lehtonen, L., & Vuokko, R. (2024). Semantic Interoperability of Electronic Health Records: Systematic Review of Alternative Approaches for Enhancing Patient Information Availability. JMIR Medical Informatics – Semantic Interoperability of Electronic Health Records: Systematic Review of Alternative Approaches for Enhancing Patient Information Availability

Pretty , F., Tamrat, T., Ratanaprayul, N., Barreix, M., Kostanjsek, N. F. I., Gaffield, M. L., … & Tunçalp, Ö. (2023). Experiences in aligning WHO SMART guidelines to classification and terminology standards. BMJ Health & Care Informatics, Volume 30, Issue 1. https://informatics.bmj.com/content/30/1/e100691#ref-1

Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine (SNOMED) International. (2025). What is SNOMED CT?. https://www.snomed.org/what-is-snomed-ct

World Health Organization. (n.d.) WHO Family of International Classifications (FIC) https://www.who.int/standards/classifications

World Health Organization. (2001). International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF) Tabular List

World Health Organization. (2019). ICD-10 Volume 2 Instruction Manual. https://icd.who.int/browse10/Content/statichtml/ICD10Volume2_en_2019.pdf

World Health Organization . (2021). WHO-FIC Classifications and Terminology Mapping – Principles and Best Practice. https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/who-fic-classifications-andterminology-mapping

World Health Organization. (2024a). Australia – Health data overview for Australia. https://data.who.int/countries/036

World Health Organization.(2024b). Welcome to the ICD universe. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jPW0sahWWg0

World Health Organization. (2025a). ICD-11 Reference Guide. https://icdcdn.who.int/icd11referenceguide/en/html/index.html#international-classification-of-diseases-icd

World Health Organization. (2025b). International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF). https://www.who.int/standards/classifications/international-classification-of-functioning-disability-and-health

World Health Organization. (2025c). ICHI Reference Guide. https://icd.who.int/dev11/Downloads/Download?fileName=ichi/ICHI_Reference_Guide.pdf

World Health Organization. (2025d). International Classification of Health Interventions (ICHI). https://www.who.int/standards/classifications/international-classification-of-health-interventions

World Health Organization. (2025e). ICD-11 Education Tool V2.0. https://icdcdn.who.int/icd11training/index.html

Image descriptions

Figure 1: A flowchart illustrating the relationships within the WHO Family of International Classifications (WHO-FIC) framework. On the left is a vertical, grey rectangle labeled “Related Classifications”. On the right is a large rectangle labeled “Foundation”. Between the two rectangles is a two-headed arrow, showing interaction in both directions. Overlapping between the Related Classifications and the Foundation is an oval labeled “Shared terminologies”, connecting or bridging those two elements. This indicates that Related Classifications share terms or vocabulary with the Foundation and its reference classifications. Inside the “Foundation” rectangle, there are two main sections: the “Reference Classifications” and “Derived Statistical Classifications and Tabulations.”

The “Reference Classifications” section is divided into three green and red blocks representing different classifications:

- “International Classification of Diseases (ICD)” in green.

- “International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health (ICF)” in red.

- “International Classification of Health Interventions (ICHI)” in grey.

Each block has horizontal arrows pointing to the “Derived Statistical Classifications and Tabulations” in shades of red and green on the right side. The overall design uses color differentiation and arrows to depict the flow and relationship among various classification systems.

Figure 2: A diagram illustrating different levels of content granularity needed to support various use cases in healthcare data classification and terminology systems. It consists of a pyramid divided into three levels, labeled from top to bottom.

At the top is a small triangular section labeled “Resource groups (Diagnosis Related Groups) DRGs,” indicating hundreds of groups. This segment is associated with health system performance, funding, and stability.

The middle section of the pyramid is labeled “Classifications (ICD-10)” and indicates supporting secondary analysis of data with stable grouped terms, representing tens of thousands of concepts.

The bottom and largest section is labeled “Clinical Terminologies (SNOMED CT).” It illustrates support for direct clinical care and has granular and dynamic content, encompassing hundreds of thousands of concepts.

Figure 3: A vertical flowchart illustrating the importance of coded healthcare data. It begins with a broad statement at the top, emphasising that data in health records is useless if inaccessible or unanalysed. Below this is a green downward arrow leading to text about how coded data supports consistent communications in patient care and health system management. Another downward arrow follows, pointing to text that states this results in better information. This is succeeded by another arrow, leading to text that states better information enables better decisions. The final arrow points to the concluding text, which asserts that better decisions ensure better health outcomes.

Figure 4: A flowchart illustrating the AR-DRG (Australian Refined Diagnosis Related Groups) assignment process. At the top, there is a section labeled “Episode data,” which leads into a series of stages numbered 1 to 5 on the left with arrows pointing right, corresponding to various steps in the process on the right.

- The first stage describes that demographic and clinical edits assess the validity of variables.

- The second stage describes episodes being assigned to a Major Diagnostic Category (MDC) based on the principal diagnosis.

- The third stage involves pre-MDC processing identifying high-cost episodes and changing MDC assignments based on other variables.

- The fourth stage assigns episodes to Adjacent DRGs (ADRGs) based mainly on diagnoses and interventions.

- The fifth stage assigns episodes to DRGs based mainly on the Episode Clinical Complexity Score (ECCS), derived from Diagnosis Complexity Levels (DCLs).

The flowchart has arrows indicating the flow from one step to the next, showing the processing pathway from episode data to the assignment of DRGs.

Figure 5: A table outlining the Australian Refined Diagnosis-Related Groups (AR-DRGs) and their complexity splits in Version 11.0. The table is divided into four rows, each with three columns labeled “DRGs in Version 11.0,” “Description,” and “Example.”

- The first row, labeled “Pre MDC,” includes “9 DRGs” with a description of “High-cost episodes” and has an example of “A13A Ventilation – 336 Hours, Major Complexity.”

- The second row, “No splits,” lists “83 DRGs” that are “assigned without the use of complexity score,” exemplified by “L61Z Haemodialysis.”

- The third row, “Split on complexity,” states “700 DRGs” are “assigned using a complexity score,” with an example of “G02B Major Small and Large Bowel Interventions, Intermediate Complexity.”

- The fourth row, “Split on other variables,” contains “9 DRGs” using variables such as “transfer status and length of stay,” demonstrated by “B70D Stroke and Other Cerebrovascular Disorders, Transferred < 5 Days.”

An ontology is a formal system that defines and organises concepts, categories, and relationships within a specific domain or field of knowledge. It's essentially a structured way of representing what exists and how different things relate to each other. At its simplest, think of ontology as a detailed map or classification system that shows how various concepts are connected and interact with one another.

An ontology is a formal description of knowledge as a set of concepts within a domain and the relationships that hold between them. It ensures a common understanding of information and makes explicit domain assumptions thus allowing organisations to make better sense of their data. (Ontotext, 2025)

An ontology-based definition, in the context of computer science and information systems, refers to a structured and formalised way of representing knowledge about a specific domain. It defines the entities, their properties, and the relationships between them, creating a shared and understandable vocabulary for users (Ontotext, 2025).

Semantic interoperability facilitates the exchange of and access to health data that are being documented in electronic health records (EHRs). The main goals of semantic interoperability development entail patient data availability and use in diverse EHRs without a loss of meaning (Palojoki et al., 2024).

The Australian Refined Diagnosis Related Groups (AR-DRG) classification provides a clinically meaningful way to relate or group the number and type of patients treated in admitted acute episodes of care to the resources required in treatment (Independent Health and Aged Care Pricing Authority, 2023e).