Leading Strategically in Health Information Management

Erin Roehrer and Matthew Springer

Learning Outcomes

- Learn about leadership theories and models relevant to strategic health information and healthcare management.

- Gain insights into strategic planning and change management in healthcare settings.

- Explore best practices for people management, including career development and succession planning.

- Understand how to measure and improve operational performance through key performance indicators (KPIs) and strategic alignment.

Introduction: Why is this topic important?

The Role of Strategic Leadership in Healthcare

Strategic leadership is essential in healthcare because it directly impacts patient outcomes, operational efficiency, and workforce engagement (Weston, 2022). Leaders need to adopt a proactive, forward-thinking approach in an environment with rapidly advancing technology, policy shifts, and evolving patient needs. Strategic leadership emphasises long-term vision, adaptability, and sustainability, instead of day-to-day operations (Fagerdal et al, 2022).

Modern healthcare systems are increasingly complex, with numerous stakeholders, regulatory requirements, and financial constraints (Dawes & Topp, 2022). The integration of digital health technologies, such as electronic health records (EHRs) and artificial intelligence (AI), presents both opportunities and challenges (Nianga, 2024). In addition, demographic shifts, including aging populations and workforce shortages, require leaders to think strategically about resource allocation and service delivery (Dawes & Topp, 2022).

Strategic leadership is directly linked to improved patient care, higher staff satisfaction, and greater organisational efficiency (Dawes & Topp, 2022). Leaders who cultivate a strong organisational culture, encourage professional development, and foster open communication contribute to a motivated workforce, enhancing patient experiences and outcomes.

What You Will Learn From This Chapter

This chapter provides health information management professionals with an understanding of strategic leadership principles, frameworks, and practical applications.

Strategic leadership in health information management requires a comprehensive understanding of various leadership theories and models. These frameworks provide the foundation for effective decision-making and guide leaders in navigating the complexities of modern healthcare systems. By examining these theories, readers can better appreciate the diverse approaches to leadership and their practical applications in strategic contexts.

The ability to engage in effective strategic planning and manage organisational change is a critical component of leadership. Leaders must be equipped to develop long-term plans that align with institutional goals while remaining adaptable to the dynamic nature of healthcare environments (Low et al, 2019). Change management strategies are essential for implementing new initiatives, improving service delivery, and fostering a culture of continuous improvement.

The management of human resources is equally important. Strategic leaders in health information management must understand best practices in people management, including methods for supporting career development and establishing robust succession planning processes. These practices ensure that healthcare organisations maintain a skilled and motivated workforce capable of meeting future challenges.

Operational performance is another key area of focus. Leaders must be able to identify, measure, and analyse KPIs to assess organisational effectiveness. Aligning these metrics with strategic objectives enables leaders to make informed decisions and drive performance improvements across the organisation. To bridge theory and practice, learners can engage with real-world case studies that illustrate the tangible impact of strategic leadership in healthcare settings. These case studies provide valuable insights into the challenges and successes experienced by healthcare leaders and offer practical lessons that can be applied in various contexts.

Finally, self-assessment activities should be integrated throughout the learning process to help individuals evaluate their own leadership capabilities. These reflective exercises encourage learners to identify personal strengths and areas for development, fostering a deeper understanding of their role as strategic leaders in healthcare.

By the end of this chapter, readers will be equipped with the knowledge and tools necessary to lead strategically in health information management, ensuring both organisational success and improved patient outcomes.

Background and Context

The Healthcare Landscape

Healthcare is an ever-evolving sector influenced by demographic shifts, technological advancements, policy changes, and economic factors (Dawes & Topp, 2022). With an ageing population, rising demand for services, and increased public expectations, healthcare leaders must continuously adapt. The push towards patient-centred care and learning-based integrated service delivery further highlights the importance of strategic leadership in ensuring that healthcare systems remain efficient and effective (Symons et al, 2021).

The Health Information Management Context

The profession of health information management (HIM) and its practice continues to evolve. HIM professionals in countries such as Australia, Canada, and the United States face challenges shaped by digital transformation, changes in the healthcare landscape, and growing demands for healthcare services. A key concern is interoperability, as health information professionals work to advocate for and enable seamless data exchange across sectors and electronic health record systems.

The rise of AI and automation has potential to transform tasks such as coding and documentation. While these technologies offer efficiency gains, they also raise concerns about data accuracy, ethical use, and workforce impact.

Cybersecurity remains a priority, with increasing threats to patient data requiring robust protection measures and constant vigilance.

The workforce itself is under pressure, with growing demand for digital and analytical skills, alongside challenges in recruitment, workforce shortages, and retention.

Regulatory compliance continues to evolve, requiring HIM professionals to adapt to changing privacy and data governance standards across jurisdictions.

Regulatory and Policy Environments Shaping Healthcare Leadership

Healthcare leadership operates within a complex regulatory and policy framework (Osunlaja et al, 2024). Leaders must be well-versed in compliance, governance, and risk management to ensure their organisations meet legal and ethical obligations. Additionally, policies related to digital health, workforce planning, and sustainability require leaders to take a long-term view when shaping organisational strategies.

Financial Pressures, Workforce Challenges, and Technological Advancements

Healthcare organisations face significant financial constraints, including funding cuts, increasing costs, and the need for efficient resource allocation (Osunlaja et al, 2024). Leaders must balance financial sustainability with delivering high-quality patient care. Workforce shortages, staff burnout, and recruitment challenges also place additional pressure on leadership, requiring investment in staff wellbeing and professional development (Weston, 2022). At the same time, emerging technologies such as AI, telehealth, and data analytics offer new opportunities to improve service delivery, streamline operations, and enhance patient outcomes (Nianga, 2024). Successful leaders leverage these advancements while managing associated risks and change resistance.

The Role of Leaders in Strategy and Planning

Healthcare leaders play a critical role in developing and executing strategies that align with both organisational goals and broader healthcare priorities (Symons et al, 2021). Strategic planning involves setting clear objectives, analysing external and internal environments, and ensuring that resources are allocated effectively (Amer et al, 2022; Chmielewska et al, 2022). Health information leaders must engage stakeholders, including clinicians, organisational executives/leaders/managers, policymakers, and patients to ensure strategic initiatives are both realistic and impactful.

Balancing Long-Term Vision with Immediate Operational Needs

One of the key challenges for healthcare leaders is striking a balance between long-term strategic objectives and the day-to-day operational demands of running a healthcare service. It is crucial to plan, though addressing immediate patient care needs, workforce issues, and regulatory requirements cannot be overlooked. Effective leaders foster a culture of ensuring that short-term decisions contribute to long-term success (Fagerdal et al, 2022).

Strategic Versus Operational Leadership

Strategic leadership focuses on vision, innovation, and long-term success, while operational leadership is centred on managing daily activities and ensuring efficient service delivery. Leaders who can integrate strategic thinking with operational expertise are better equipped to drive sustainable change, improve patient outcomes, and enhance organisational performance (Fagerdal et al, 2022). Understanding when to prioritise strategy over operations—and vice versa—is a crucial skill for healthcare leaders in today’s complex environment. In the health information management context, it is important to understand technological and other changes that could impact upon strategy and direction. Strategic planning for health information management services could involve using tools and techniques such as environmental scanning, strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats, or other approaches.

Theoretical Foundations: Leadership, Strategy, and Change Models

Strategic leadership in healthcare demands a nuanced approach. HIM professionals must navigate complex challenges while balancing patient care, staff needs, and operational efficiency. To effectively lead in this dynamic environment, healthcare leaders must access a range of leadership theories, strategic planning models, and change management frameworks. This section explores several theories and models relevant to strategic leadership in healthcare, offering healthcare leaders tools and frameworks to guide their decisions and actions in an ever-changing landscape.

Leadership Theories Relevant to Strategic Leadership in Healthcare

1. Transformational Leadership

Transformational leadership is one of the most widely recognised leadership theories, developed by James MacGregor Burns in the late 1970s (Burns, 1978). It is effective in driving cultural change and improving staff engagement. There are many components to transformational leadership; however, the basic elements are where leaders create a relatable, inspirational, intellectually challenging working environment with the ability to support people through their individual contexts (Eaton et al, 2024). In healthcare, this style of leadership is crucial, as it helps to overcome barriers such as resistance to change, staff burnout, or stagnation (Fagerdal et al, 2022).

Transformational leaders create an environment that encourages collaboration and continuous learning, essential in the rapidly evolving field of healthcare. By leading with empathy and enthusiasm, they empower their staff to go beyond mere compliance and strive for excellence in patient care (Labrague, 2024). For example, a hospital leader using transformational leadership might inspire and encourage staff to embrace new technologies or methodologies that improve patient outcomes, despite the initial reluctance to adopt new systems. Additionally, transformational leaders are adept at communicating the broader goals of the organisation, helping staff understand their role in achieving these objectives and improving patient care.

In the context of healthcare, transformational leadership also encourages a culture of inclusivity, where diverse ideas are valued, and creative solutions to problems are encouraged (Labrague, 2024). This leadership style aligns with healthcare’s shifting focus on patient-centred and integrated care, as it nurtures collaboration across departments, improving communication and coordination within multidisciplinary teams.

2. Servant Leadership

Servant leadership is a leadership style focused on putting the needs of others, particularly employees and patients, first. The primary goal of servant leaders is to serve their teams by providing the tools, resources, and support necessary for them to succeed, in simple terms – to lead as a ‘servant’ to others (van Dierendonck & Patterson, 2025).

This ‘service’ could involve providing mental health support for staff, ensuring that they have access to appropriate training and development opportunities, or advocating for patient safety and dignity in every decision. In healthcare settings, where stress, emotional exhaustion, and burnout are common, a servant leader’s emphasis on empathy and support can help sustain the morale and commitment of staff.

This model of leadership encourages a focus on collaboration, humility, and empowerment, helping to build trust within teams. By prioritising the needs of others, servant leaders create a sense of shared responsibility and ownership of organisational goals, thereby fostering a positive work culture and improving overall performance (Demeke et al, 2024).

3. Adaptive Leadership

Adaptive leadership is particularly useful in healthcare, where leaders must respond to complex challenges and changing conditions. This leadership theory encourages leaders to remain flexible and responsive, promoting continuous learning and the ability to navigate ambiguity (Kuluski et al, 2021; Fagerdal et al, 2022). The healthcare environment is often characterised by uncertainty, whether due to emerging medical technologies, crises such as pandemics, or changes in policy. Adaptive leaders can manage these dynamic challenges by promoting a mindset of experimentation and innovation.

A key component of adaptive leadership is the ability to encourage collaboration and shared problem-solving. Leaders separate technological solutions from adaptive solutions during times of change, and considering the assumptions made regarding behaviours and motivations to that change (Kuluski et al, 2021). Healthcare leaders must not only guide their teams, but also empower them to find creative solutions to emerging problems. Adaptive leaders embrace feedback and use it to drive improvements, recognising that the challenges healthcare organisations face often require solutions that emerge through trial and error, collaboration, and iterative processes.

Adaptive leadership also fosters resilience within teams by encouraging leaders to face challenges head-on and providing the resources and support needed to manage change effectively (Kuluski et al., 2021). In healthcare, where staff may feel overwhelmed by constant change, adaptive leadership seeks to position change as an opportunity for growth rather than a threat to stability. This view may be somewhat idealistic, as not all staff readily embrace change, particularly in high-pressure environments where workload demands, resource constraints, and change fatigue are ongoing challenges. Adaptive leadership provides a valuable framework for navigating complexity; however, its effectiveness relies on organisational culture, staff readiness, and the presence of adequate support structures to enable meaningful adaptation (Kuluski et al., 2021).

Strategy and Planning Models in Healthcare

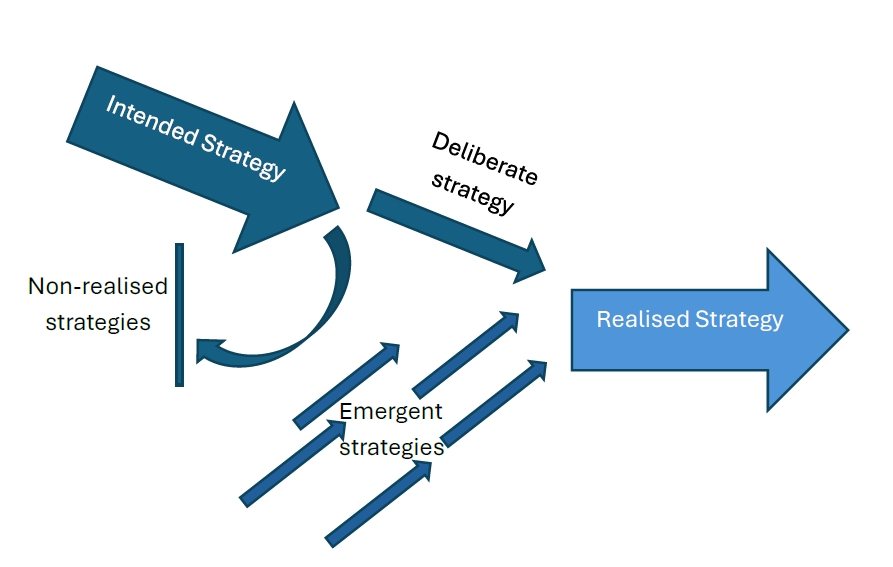

1. Mintzberg’s (2007) Emergent vs. Deliberate Strategy

Mintzberg’s (2007) theory of emergent and deliberate strategy emphasises the need to balance structured planning with the ability to adapt to real-world changes. Deliberate strategies are planned, with leaders setting clear goals and directives, while emergent strategies arise organically in response to unforeseen events or market shifts (Foss et al, 2022).

Source: Adapted from Figure 1.2 in Mintzberg (2007). [Go to image description]

In healthcare, a deliberate strategy may involve long-term planning around financial management, service delivery, or regulatory compliance. However, healthcare leaders must also be prepared to adopt an emergent approach in response to unanticipated challenges, such as a sudden surge in patient volume, new healthcare regulations, or a public health crisis. The ability to respond effectively to such changes, while still adhering to the core principles of the organisation, is essential for success (Mintzberg, 2007; Foss et al, 2022).

By integrating both deliberate and emergent strategies, healthcare leaders can develop flexible, adaptable plans that allow for the execution of long-term goals while remaining responsive to immediate challenges.

2. The Balanced Scorecard Approach

The balanced scorecard approach is a comprehensive framework that helps leaders align business activities to the organisation’s vision and strategy (Kaplan 1992). In healthcare, this model is used to improve performance measurement and management across four key perspectives: financial, customer, internal processes, and learning and growth (Amer et al, 2022).

Source: Concept derived from figure “ECI’s Balanced Business Scorecard” in Kaplan and Norton (1992)

Healthcare leaders can measure and track progress toward organisational objectives across these diverse dimensions using the balanced scorecard. For example, from a financial perspective, leaders might assess the cost-effectiveness of treatment plans. From a customer perspective, the focus would be on patient satisfaction and experience. Internal processes would encompass the efficiency of service delivery; while learning and growth would involve staff development and knowledge-sharing initiatives.

Implementing a balanced scorecard approach allows healthcare organisations to gain a holistic view of their performance, ensuring that all areas are aligned with the organisation’s strategic goals (Amer et al, 2022).

3. Porter’s (1989) Five Forces and Competitive Strategy in Healthcare

Porter’s (1989) five forces framework is invaluable for healthcare leaders seeking to understand market competition and develop a sustainable competitive advantage. The framework helps leaders assess the competitive pressures within the healthcare industry, including the threat of new entrants, bargaining power of suppliers, bargaining power of patients, the threat of substitute services, and the intensity of competitive rivalry (Mahat, 2019).

Source: Concept derived from Figure 10.1 in Porter (1989)

In a healthcare setting, this framework can be used to assess factors such as the increasing number of healthcare providers in the market, the influence of insurance companies, and the availability of alternative treatments. By understanding these dynamics, healthcare leaders can negotiate better partnerships, optimise service offerings, and create sustainable competitive advantages that allow them to deliver superior value to patients.

Change Management Frameworks

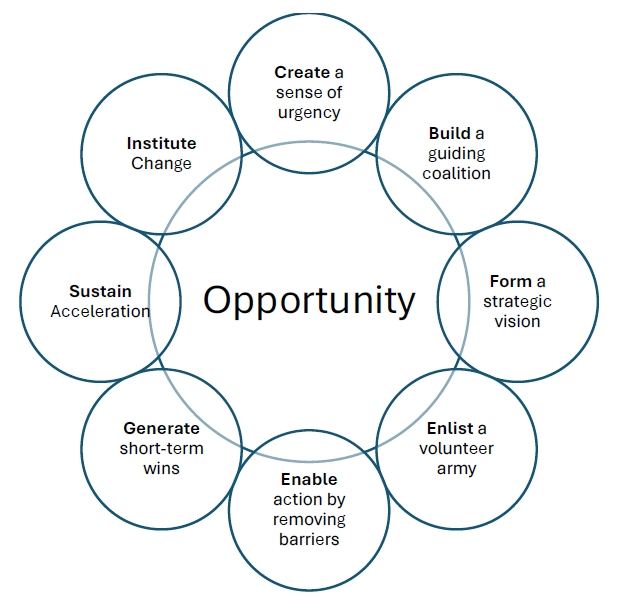

1. Kotter’s (2012) 8-Step Change Model

Kotter’s (2012) 8-step change model provides a structured, step-by-step approach to managing organisational change. It is one of the more popular change models used in healthcare, along with Lewin’s (1947) change management model (Harrison et al, 2021). Kotter’s (2012) model begins by creating a sense of urgency around the need for change and ends with embedding new practices into the organisation’s culture. In healthcare, this model is particularly helpful for introducing new processes, technologies, or organisational structures. It then moves to building a guiding group that will then form a strategic vision to consult with a larger audience. The model’s fourth step is focused on enlisting volunteers and then moving onto helping action/change to occur by removing barriers. Generating short term wins is the sixth stage, followed by ensuring motivation and momentum of change occurs. The last stage of Kotter’s (2012) model focuses on embedding the change.

Source: Adapted from Leading Change framework in Kotter (2012)

By following Kotter’s (2012) steps, such as building a guiding coalition, communicating the vision for change, and empowering action, healthcare leaders can ensure that the change process is carried out smoothly, with minimal resistance and maximum engagement from staff.

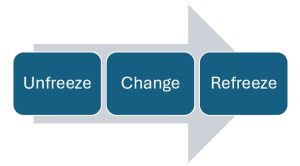

2. Lewin’s (1947) Change Management Model

Lewin’s (1947) change management model is a simple yet effective framework for guiding organisational change. The model consists of three phases: unfreezing, changing, and refreezing (Lewin, 1947).

Source: Adapted from model in Lewin (1947)

The unfreezing phase involves creating the motivation for change and preparing the organisation for the transition (Lewin, 1947). The changing phase is where the actual transformation occurs, such as the implementation of new practices or systems. Finally, the refreezing phase focuses on stabilising the change and ensuring that new practices are embedded within the organisation.

In healthcare, Lewin’s (1947) model is useful for guiding staff through transitions, ensuring that they understand the need for change, are actively involved in the change process, and are supported as new practices are integrated into their daily work.

3. McKinsey’s 7S Framework

McKinsey’s 7S framework is based on the idea that seven elements, strategy, structure, systems, shared values, style, staff, and skills, must be aligned for an organisation to achieve its objectives (Peters & Waterman, 1985; Chmielewska et al, 2022). In healthcare, this model helps leaders assess the interdependencies between different parts of the organisation and ensure that all elements are working in harmony to support change.

For example, if a healthcare organisation is adopting a new electronic health record system, McKinsey’s 7S framework helps leaders ensure that the strategy for implementation is aligned with the structure of the organisation, the systems in place to support the change, and the skills of the staff.

Strategic leadership in healthcare requires a thorough understanding of leadership theories, strategic planning models, and change management frameworks. By integrating theories such as transformational and servant leadership with tools like balanced scorecard and Kotter’s (2012) 8-step change model, healthcare leaders can navigate complex challenges and drive sustainable improvements.

Key Implications for Practice

People Management in Health Information Management

Effective leadership in health information management relies heavily on people management, as the workforce is one of the most critical assets in any healthcare organisation. An engaged, skilled, and resilient workforce contributes to optimal patient care, operational efficiency in the health information service, and organisational success. Strategic leaders must invest in the development of their staff, from leadership programs to coaching initiatives, ensuring that the team is prepared to face the challenges of an increasingly complex healthcare environment.

Leadership Development Programs

One of the most effective ways to build a sustainable leadership pipeline within healthcare organisations is through structured leadership development programs. These programs are designed to equip emerging leaders with the skills and knowledge required to navigate the complex and often turbulent healthcare landscape. Given the fast pace of change in healthcare, leaders need to be agile, adaptable, and capable of making decisions that affect both operational and clinical outcomes.

Leadership development programs typically combine formal education with experiential learning. Formal training may include courses on strategic decision-making, ethics, healthcare policy, and patient-centred care. These academic modules provide emerging leaders with the theoretical frameworks necessary for making informed decisions. In parallel, experiential learning opportunities, such as job rotations, shadowing senior leaders, or participation in strategic decision-making processes, help these individuals gain practical experience and develop leadership competencies in real-world contexts.

Activity

Read Leadership development in health information management (HIM): Literature review [PDF]

Identify the competencies to inform the development of a relational style of leadership described in the paper.

Succession Planning

Succession planning is another vital component of people management in healthcare. This proactive process helps ensure that an organisation is prepared for leadership transitions, reducing the potential for disruption and maintaining continuity in strategic decision-making (Low et al, 2019). Succession planning is especially critical in healthcare organisations, where leadership changes can have far-reaching implications for patient care, staff morale, and organisational stability (Dawes & Topp, 2022).

Effective succession planning involves identifying potential leaders early on and providing them with the necessary training, experiences, and exposure to strategic decision-making. By nurturing internal talent, organisations can create a pool of qualified candidates ready to step into leadership roles as the need arises, reducing reliance on external recruitment, which can be costly and time-consuming (Osunlaja et al., 2024). It also promotes a culture of career progression and stability within the organisation, boosting employee retention and engagement.

Healthcare leaders can identify potential successors by assessing their performance, leadership potential, and alignment with the organisation’s values and strategic goals. Mentoring and coaching are key tools in this process, as they provide a supportive environment for emerging leaders to gain insight into the responsibilities of senior leadership positions.

Coaching and Mentoring

Coaching and mentoring programs are effective for fostering professional growth and development at all levels of an organisation. These programs facilitate knowledge transfer and help individuals enhance their skills, especially crucial in the fast-paced and ever-evolving healthcare sector (Low et al, 2019; Osunlaja et al, 2024). Senior leaders play a pivotal role in developing future leaders by offering guidance, support, and feedback, contributing to both career progression and overall organisational success (Dawes & Topp, 2022).

Coaching is typically focused on improving specific skills or addressing challenges faced by individuals, such as decision-making, communication, or team management. It is usually a one-on-one process in which a more experienced leader helps work through challenges, set goals, and identify strategies for personal and professional development.

On the other hand, mentoring is a longer-term relationship where senior leaders provide broader guidance and advice to junior staff. It often involves sharing experiences, offering career advice, and helping mentees navigate the complexities of the healthcare environment. A mentoring relationship can be invaluable in developing leaders who not only understand the technical aspects of healthcare, but also the organisational culture, values, and vision that drive the organisation forward (Low et al, 2019).

By encouraging coaching and mentoring, healthcare leaders can build a culture of continuous learning and professional development, essential for long-term success.

Operational Performance Management in Healthcare

In addition to focusing on people management, strategic healthcare leaders must also prioritise operational performance. Achieving high levels of efficiency and effectiveness in day-to-day operations is crucial to ensuring that healthcare organisations provide high-quality patient care while maintaining financial and operational sustainability.

Key Performance Indicators (KPIs)

KPIs are powerful tools for measuring the success of operational strategies and initiatives. KPIs allow healthcare leaders to assess both the effectiveness and efficiency of their organisations, identifying areas that require improvement and driving accountability at all levels of the organisation (Amer et al, 2022; Kaplan, 1992). Common healthcare KPIs include patient satisfaction scores, wait times, staff turnover rates, and financial performance metrics, such as revenue and cost management. HIM professionals are frequently involved in generating and responding to KPIs within their organisations. Examples may include generating clinical indicator reports, responding to KPIs around the clinical coding function (Low et al, 2019).

KPIs provide tangible benchmarks that healthcare leaders can use to guide decision-making and track progress over time. By focusing on these metrics, leaders can align operational efforts with strategic objectives and make data-driven decisions that lead to improved patient care and organisational performance.

Strategic Alignment of Operational Plans

In any organisation, it is essential that day-to-day operations align with the broader strategic objectives. In healthcare, this alignment ensures that operational decisions support the overarching goal of improving patient outcomes while maintaining operational efficiency (Amer et al, 2022; Weston, 2022). Leaders must ensure that the organisation’s strategic direction is clearly communicated and embedded into daily workflows.

This alignment can be achieved through clear communication of goals, integration of strategic initiatives into daily practices, and fostering a culture of continuous improvement (Low et al, 2019; Harrison et al, 2021). For example, a healthcare leader might communicate a strategic goal to reduce patient wait times, and operational plans would then be adjusted to ensure that resources, processes, and staff are aligned with this objective. Staff must be empowered to contribute to these goals by having the appropriate training and support to implement changes in practice.

Resource Management and Decision-Making

Healthcare leaders must make informed decisions about resource allocation, including workforce planning, budget management, and technology investments. Effective resource management ensures that the right resources are in place to support patient care and operational goals (Weston, 2022; Osunlaja et al, 2024). Given the limited nature of resources in most healthcare settings, leaders must prioritise and allocate them strategically. The health information service in a large hospital will be accountable for the budget allocated to them, and must manage within this budget and advocate through a business case when additional resources are required (Low et al, 2019).

Data-driven decision-making plays a key role in resource management. By leveraging performance analytics and input from stakeholders, healthcare leaders can make informed choices about where to invest resources to achieve the greatest impact (Amer et al, 2022). For example, investing in technology can streamline administrative tasks, reduce errors, and improve patient care, while careful workforce planning can ensure that staff levels are adequate to meet demand without overburdening employees.

Case Studies

Case Study: Bringing a Hospital’s Strategic Plan to Life

In 2022, St. Mark’s Hospital, a major regional healthcare provider in Australia, set out to improve patient care and streamline operations through a new strategic plan. The leadership team, led by CEO Maria Sanchez, knew that every department needed to work together rather than operating in isolation for the plan to succeed.

A key challenge was that different teams were focused on their own tasks without a clear link to the hospital’s broader goals. This lack of coordination led to inefficiencies and missed opportunities to improve patient outcomes. To tackle this, Maria and her team organised a series of planning sessions with department heads, clinicians, and staff to ensure that everyone understood the hospital’s priorities and how their work contributed to them.

During these sessions, teams identified practical ways to align their efforts with the hospital’s strategy. For example, the IT team improved patient data systems to support better communication between departments, while nurses introduced new processes to reduce wait times. Regular progress reviews were set up, with each department reporting on their achievements and challenges every quarter.

Within a year, the hospital saw real improvements. Patient satisfaction scores increased by 15%, and clinical outcomes, such as reduced readmission rates, also improved. By focusing on collaboration, communication, and clear objectives, Maria and her team helped turn the hospital’s strategic vision into real, measurable change.

Case Study: Navigating Resistance to Healthcare Technology Change

When Greenfield Medical Centre in New Zealand decided to introduce a new EHR system in 2021, Chief Information Officer Dr John Hayes knew it would be a challenging transition. While the new system promised better data management, streamlined workflows, and improved patient care, many staff were hesitant to move away from the familiar processes they had used for years.

Dr Hayes recognised that resistance stemmed from concerns about the learning curve, potential disruptions to patient care, and fear of change. To address this, he focused on clear communication, hands-on training, and strong leadership support. He reassured staff that the new system was designed to help them, not replace them, and regularly highlighted its long-term benefits, such as reducing errors and making documentation easier.

A tailored training program was introduced, catering to different staff needs. Clinicians received practical, hands-on training with IT support on hand, while administrative staff attended workshops focused on data entry and system navigation. To minimise disruptions, the rollout was staggered, allowing teams to adapt gradually.

Despite these efforts, adoption was slower than expected. Some senior clinicians were reluctant to fully engage with the system, which influenced their teams’ attitudes. Recognising this, Dr Hayes met with department heads individually to address their concerns and demonstrate how the system would enhance patient care. Gaining their support was a turning point in encouraging wider acceptance.

Six months later, the hospital saw significant improvements. Documentation errors dropped by 30%, and staff reported greater efficiency in managing patient records. By focusing on communication, training, and leadership engagement, Dr Hayes helped the organisation successfully navigate a major technological change.

Activity – Interactive learning

Summary

For health information management leaders, you will know if you are successful if:

As a leader in health information management, success is not just about achieving goals; it is about ensuring that your strategic initiatives translate into tangible improvements in health record documentation, clinical coding accuracy, integration of digital health tools, safety and quality of patient care, operational efficiency, and overall organisational performance. You will know you are successful if your strategic initiatives lead to measurable improvements in these areas and the health information services provided are integral to the successful operation of the organisation.

Another sign of success is the engagement and alignment of your team with the organisation’s strategic goals. If your team members feel connected to the overall mission and are actively contributing to its achievement, this is a strong indication that your leadership is fostering a culture of collaboration and purpose. Successful leadership also involves the ability to effectively lead change while maintaining stability and staff morale. As a leader, you will know you are successful if you can introduce new processes, technologies, or strategies without causing undue stress or disruption. If employees feel supported, informed, and involved in the change process, this indicates that you are navigating transitions smoothly.

Lastly, measurable progress towards long-term organisational objectives, as shown through KPIs, is a clear indicator of success. If the data reflect progress, whether in terms of patient outcomes, cost-efficiency, or staff performance, your leadership is on the right track. Achieving KPIs aligned with the organisation’s vision ensures that your strategic direction is not only effective but sustainable.

Success as a health information leader is defined by the positive, measurable outcomes of your strategic initiatives, the engagement and development of your team, and the ability to lead change effectively while maintaining organisational stability.

References

Amer, F., Hammoud, S., Khatatbeh, H., Lohner, S., Boncz, I., & Endrei, D. (2022). The deployment of balanced scorecard in health care organizations: Is it beneficial? A systematic review. BMC Health Services Research, 22, 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-07452-7

Burns, J. M. (1978) Leadership. New York: Harper & Row.

Chmielewska, M., Stokwiszewski, J., Markowska, J., & Hermanowski, T. (2022). Evaluating organizational performance of public hospitals using the McKinsey 7-S framework. BMC Health Services Research, 22, 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-021-07402-3

Dawes, N., & Topp, S. M. (2022). A qualitative study of senior management perspectives on the leadership skills required in regional and rural Australian residential aged care facilities. BMC Health Services Research, 22(1), 667. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-08049-4

Demeke, G. W., van Engen, M. L., & Markos, S. (2024). Servant leadership in the healthcare literature: A systematic review. Journal of Healthcare Leadership, 1-14. https://doi.org/10.2147/JHL.S440160

Eaton, L., Bridgman, T., & Cummings, S. (2024). Advancing the democratization of work: A new intellectual history of transformational leadership theory. Leadership, 20(3), 125-143. https://doi.org/10.1177/17427150241232705

Fagerdal, B., Lyng, H. B., Guise, V., Anderson, J. E., Thornam, P. L., & Wiig, S. (2022). Exploring the role of leaders in enabling adaptive capacity in hospital teams–A multiple case study. BMC Health Services Research, 22(1), 908. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-022-08296-5

Foss, N. J., McCaffrey, M. C., & Dorobat, C.-E. (2022). “When Henry Met Fritz”: Rules as organizational frameworks for emergent strategy process. Journal of Management Inquiry, 31(2), 135-149. https://doi.org/10.1177/10564926211031290

Harrison, R., Fischer, S., Walpola, R. L., Chauhan, A., Babalola, T., Mears, S., & Le-Dao, H. (2021). Where do models for change management, improvement and implementation meet? A systematic review of the applications of change management models in healthcare. Journal of Healthcare Leadership, 85-108. https://doi.org/10.2147/JHL.S289176

Kaplan, R. S. (1992). The Balanced Scorecard – Measures That Drive Performance. Harvard Business Review, 70(1).

Kotter, J. (2012). Steps for leading change. Kotter International.

Kuluski, K., Reid, R. J., & Baker, G. R. (2021). Applying the principles of adaptive leadership to person‐centred care for people with complex care needs: Considerations for care providers, patients, caregivers and organizations. Health Expectations, 24(2), 175-181. https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.13174

Labrague, L. J. (2024). Relationship between transformational leadership, adverse patient events, and nurse-assessed quality of care in emergency units: The mediating role of work satisfaction. Australasian Emergency Care, 27(1), 49-56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.auec.2023.08.001

Lewin, K. (1947). Frontiers in group dynamics: Concept, method and reality in social science; social equilibria and social change. Human Relations, 1(1), 5-41. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872674700100103

Low, S., Butler-Henderson, K., Nash, R., & Abrams, K. (2019). Leadership development in health information management (HIM): Literature review. Leadership in Health Services, 32(4), 569-583 https://doi.org/10.1108/LHS-11-2018-0057

Mahat, M. (2019). The competitive forces that shape Australian medical education: An industry analysis using Porter’s five forces framework. International Journal of Educational Management, 33(5), 1082-1093. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJEM-01-2018-0015

Mintzberg, H. (2007). Tracking strategies: Toward a general theory. Oxford University Press.

Nianga, Z. W. (2024). Leveraging AI for Strategic Management in Healthcare: Enhancing Operational and Financial Performance. Journal of Intelligence and Knowledge Engineering (ISSN: 2959-0620), 2(3), 1. https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Zefeng-Wang-4/publication/387658270_Leveraging_AI_for_Strategic_Management_in_Healthcare_Enhancing_Operational_and_Financial_Performance/links/67d24b77d75970006508772c/Leveraging-AI-for-Strategic-Management-in-Healthcare-Enhancing-Operational-and-Financial-Performance.pdf

Osunlaja, O., Enahoro, A., Maha, C. C., Kolawole, T. O., & Abdul, S. (2024). Healthcare management education and training: Preparing the next generation of leaders-a review. International Journal of Applied Research in Social Sciences, 6(6), 1178-1192. https://doi.org/10.51594/ijarss.v6i6.1209

Porter, M. E. (1989). How competitive forces shape strategy (pp. 133-143). Macmillan Education UK. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-20317-8_10

Symons, T., Zalcberg, J., & Morris, J. (2021). Making the move to a learning healthcare system: has the pandemic brought us one step closer? Australian Health Review, 45(5), 548-553. https://doi.org/10.1071/AH21076

van Dierendonck, D., & Patterson, K. (2025). Servant leadership: An introduction. In Servant leadership: Developments in theory and research (pp. 3-14). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-69922-1_1

Peters, T. J. & Waterman, R. H. (1985). In Search of Excellence. Nursing Administration Quarterly, 8(3), 85-86.

Weston, M. J. (2022). Strategic planning for a very different nursing workforce. Nurse leader, 20(2), 152-160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mnl.2021.12.021

Image descriptions

Figure 1: The diagram illustrates Mintzberg’s concept of how strategies form. On the left, a large arrow labeled “Intended Strategy” points right. Part of this arrow curves downward into a vertical barrier labeled “Non-realised Strategies,” showing strategies that do not get implemented. The remainder of the intended strategy continues right as a smaller arrow labeled “Deliberate Strategy.”

Beneath this, several smaller diagonal arrows labeled “Emergent Strategies” rise from the bottom toward the right, converging with the deliberate strategy. Together, these arrows combine into a large arrow on the far right labeled “Realised Strategy,” symbolising the strategies that are ultimately carried out.

This visual highlights that realised strategy is a blend of deliberate strategies (planned and implemented) and emergent strategies (developed in response to changing circumstances), while some intended strategies are never realised.