Health Information Management

The Foundation for Good Health

Sheree Lloyd; Gina Banfield; and Willy Chan

Learning Outcomes

- Understand the features of healthcare systems and the principles, benefits, and practices of health information management.

- Analyse the various health information management contexts and forms, including national and international settings.

- Describe health information uses in evaluating health system performance, implementing data-driven resource allocation, and leveraging data for scientific and clinical research advancements.

Introduction

Health information from information systems is essential to managing and delivering healthcare. It helps clinicians diagnose, plan treatment, and manage ongoing care, while supporting managers and leaders in decision-making, planning, and resource allocation. Health information aids government departments, private companies, and agencies that set policies, strategies, and funding for healthcare providers. It allows them to understand health system performance, plan services, and respond to emergencies. The World Health Organization (WHO) outlines six components of strong healthcare systems: health information systems, service delivery, a capable health workforce, access to essential medicines and technologies, health financing, and effective leadership and governance. These services should be safe, effective, equitable, and available to everyone when required. Many countries’ citizens do not have universal health coverage leaving people vulnerable when exposed to illness or injury (UHC2030, 2024). Good health is fundamental to both community and individual prosperity.

Health information systems support diagnosis and personalised treatment by providing healthcare professionals with comprehensive, up-to-date records. Health information systems improve patient safety by alerting providers to potential risks, such as drug interactions or allergies (Stukus, 2019; Woods, Canfell, et al., 2023). Importantly, healthcare information systems contribute to public health improvements and disease monitoring. Aggregated data from health information systems enable disease surveillance and monitoring of population health trends, aiding in the early detection of disease outbreaks and demographic trends, and informing health policy and planning. Researchers use health data to study disease patterns, develop treatments, and improve healthcare delivery (Hardy, 2024; Woods, Canfell, et al., 2023). Predictive analytics enable the identification of at-risk populations, assisting healthcare providers and policymakers to implement preventive measures and allocate resources efficiently (Van Calster et al., 2019; Woods, Canfell, et al., 2023).

Understanding the structure and operation of healthcare systems is fundamental to working as a health information management professional. This chapter begins by describing the organisation of healthcare systems, highlighting how they are constituted and function to deliver services and provide patient care. Health information management (HIM) principles, benefits, and practices are then described, emphasising their critical role in governing and maintaining organised, accurate, and accessible health data. HIM supports clinical, strategic, managerial, and operational decision-making through the provision of high quality, complete, and timely information. HIM professionals play a critical role in information governance and designing systems, policies, and procedures to protect data privacy and security.

The various HIM contexts and forms include understanding the work completed by HIM professionals in national and state governments, hospitals, general practices, registries, consultancies, and the impact of HIM at local, national, and international levels. By comparing how HIM works in these varied contexts, we can better understand the diverse approaches to managing health information and the related challenges and opportunities. This chapter discusses the various types of health information management, from traditional paper-based records to electronic medical and health records (Electronic Medical Records (EMRs)/Electronic Health Records (EHRs)) and integrated health information systems.

The chapter introduces health information uses and explores how health data can be utilised to evaluate health system performance. We will explore the significance of the foundational nature of data and its role in decision making in healthcare. The chapter describes the importance of collecting data to accurately track activities such as admissions, diagnoses, and episodes of care, and how this supports clinical care, safety, quality, planning, decision making, and resource allocation. Health information also plays a key role in research, driving scientific and clinical advancements. Understanding these uses highlights the role of health data in shaping healthcare.

According to the WHO (World Health Organization, 2021a), several foundational elements are essential for building strong healthcare systems, including a well-trained and motivated health workforce, governance, health information systems, robust infrastructure, and a reliable supply of essential medicines and technologies. Adequate funding, strong health plans, and evidence-based policies are also crucial components. Primary health care is widely recognised as underpinning a resilient health system, bringing services closer to communities and ensuring that health care is accessible to all (UHC2030, 2024; World Health Organization, 2021b).

Australia has a strong healthcare system by international standards, providing access to a range of services via universal health insurance schemes supported by taxpayer contributions (Commonwealth Fund, 2024). Australia’s healthcare system ranks highly compared to similar countries and excels in care processes and equity (Commonwealth Fund, 2024). However, there is room for improvement, and the Australian healthcare system faces challenges in access to care, particularly regarding wait times for specialist appointments and elective surgeries (Commonwealth Fund, 2024).

Social Determinants of Health and Healthcare Systems

Understanding the social determinants of health (SDH) is important because they influence health outcomes. SDH are the conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work, and age. These conditions are influenced by factors such as economic policies, social norms, and political systems (World Health Organization, 2025). They cover things such as education, access to health services, housing conditions and poverty. Addressing the SDH is crucial for improving health equity, and research indicates that SDH can be more influential than healthcare or lifestyle choices in determining health outcomes (World Health Organization, 2025).

Improving SDH can reduce burdens of disease and mortality (World Health Organization, 2025). Indicators reported by the WHO (2025) through the global health observatory provides a valuable source of intelligence. The observatory reports on priority health issues; for example, disease mortality and burden, HIV/AIDS, immunisation, malaria, tuberculosis, water and sanitation, non-communicable diseases and risk factors, health systems, environmental health, violence and injuries, and equity (World Health Organization, 2025).

SDH impact healthcare systems by affecting resource allocation, access to care, and health outcomes. Healthcare policy makers and governments in Australia often work with sectors such as education, housing, and transportation to address SDH. Collaboration across sectors can improve health interventions and create a more supportive environment for maintaining the health of communities and the population.

Universal Health Coverage (UHC)

UHC is important and ensures that all individuals have access to essential healthcare services without financial hardship, promoting healthier societies and reducing inequality (UHC2030, 2024). Good health and access to UHC fosters economic growth by improving workforce productivity and reducing the economic burden of untreated illnesses (UHC2030, 2024). Different countries will fund and organise UHC in ways that support the achievement of healthcare goals. In Australia, UHC is provided through Medicare [opens in new tab]. Medicare covers the eligible population for a range of health services, including medical consultations, hospital services for public patients, surgical procedures, prescription medicines, eye tests, pathology tests, and diagnostic imaging and is funded through a taxation levy.

In Indonesia, the government has implemented Jaminan Kesehatan Nasional, a national health insurance program aiming to provide UHC for its population (Maulana et al., 2022). In contrast, Singapore uses a multi-tiered healthcare financing system, including compulsory savings through MediSave, risk pooling via MediShield Life, and government subsidies to achieve affordable and sustainable healthcare for its citizens (Chopra, 2024).

In the United Kingdom, the National Health Service (NHS) is a publicly funded healthcare system that provides comprehensive health services to all UK residents. It was established in 1948 with the founding principles that services should be comprehensive, universal, and free at the point of delivery (Harris & Cresswell, 2024).

When individuals are unwell, a robust healthcare system can provide healthcare services when and where they are required. Strong healthcare systems also prioritise prevention and health promotion, focusing on preventing illness and encouraging healthy lifestyles through public health initiatives (Health Foundation, 2019). Addressing health inequalities by tackling social determinants that impact health such as housing, education, and income to reduce disparities in health outcomes is also critical. Involving local communities in the design and delivery of health services is vital to ensure they meet local needs and preferences (Health Foundation, 2019). Mature healthcare systems ensure that care services are well-coordinated and can respond to emergencies such as floods, fires, disease outbreaks and pandemics. Effective leadership and management are crucial for maintaining high-quality services and efficient resource use within any healthcare system.

Data and Information

Health data are crucial for improving healthcare safety, quality, and efficiency and essential for evaluating healthcare system performance, identifying areas for improvement, and implementing evidence-based policies. Health data also help track outcomes and health trends, enabling tailored interventions to improve safety and quality. Effective use of health data ensures efficient resource allocation to address the most pressing health needs. Health data play a critical role in strengthening healthcare systems by informing policy decisions, helping governments develop strategies to improve health outcomes, and achieving UHC. It is crucial for monitoring health system performance, identifying gaps, and evaluating the impact of health interventions. Health data supports disease surveillance and response, enabling timely detection and management of health threats. Routine health data supports continuous improvement in service delivery, addressing challenges such as waiting times and health inequalities. Health data drives innovation by providing insights that lead to new treatments and technologies. It also enables personalised care by helping healthcare providers understand individual patient needs and preferences. Information is a valuable asset in the health sector (Hanson, 2011) and is data that has been processed, organised, or interpreted to have meaning and relevance.

Activity: Understanding the Australian Health Performance Framework

Objective

- To understand the key components and indicators of the Australian Health Performance Framework (AHPF) [opens in new tab]

- Access the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare (AIHW) website [opens in new tab].

Introduction

Visit the AIHW website and read the overview of the AHPF. Focus on its purpose and importance in assessing health and healthcare performance in Australia.

Exploring the Framework

- View the AHPF conceptual framework diagram.

- Identify the four key domains: determinants of health, health system, health status, and societal impacts.

- Note down one key indicator from each domain and briefly describe what it measures and why it is important.

Reflection

Reflect on how these indicators provide a comprehensive assessment of health and healthcare performance. Reflect on data sources and quality.

Write a short paragraph summarising your understanding of the AHPF, the role of data, and how the framework guides health policy and improves health outcomes.

What is Health Information Management (HIM)?

‘Good health information needs to be seen as an asset. To fully appreciate the value of information, health facilities need to recognise the importance of a clear vision for information management and how it can support the overall transformation of Health’ (Hanson, 2011).

HIM is a discipline focused on managing health data and information to support patient care, healthcare planning, and funding. It involves collecting, classifying, analysing, and reporting clinical and administrative data to meet medical, legal, ethical, and administrative requirements (Health Information Management Association of Australia (HIMAA), 2024). HIM professionals [opens in new tab] have expertise in health record management, clinical coding and classification, information management, human resource management, and healthcare processes. They play key roles in ensuring data integrity, information governance, and health informatics, while continuously modernising HIM core foundations of HIM (Kemp et al., 2021). HIM professionals work across a variety of sectors and roles, including healthcare, academia, research, health IT, and others (Kemp et al., 2021). These professionals have a unique set of knowledge and skills encompassing biomedical sciences; information science and technology; the legal aspects of health information management, including privacy; and the integration of clinical and financial information (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2024).

HIM professionals develop information practice specialisation within eight core areas, applicable in multiple settings: health classification, clinical documentation integrity, health information privacy, health record and health information service management, digital health and health informatics, health funding and performance information management, health data and information governance, and health information teaching, academia and research (Health Information Management Association of Australia (HIMAA), 2025b). Health Information Managers can work within and across all six areas of specialisation as well as in broader roles such as in project, business development, patient safety and quality, and executive management (Health Information Management Association of Australia (HIMAA), 2025).

Benefits and Uses of Health Information Management

Health System Performance – Metrics for Evaluating Efficiency, Effectiveness, and Safety

HIM professionals are responsible for collecting, analysing, and managing health data, which is essential for assessing technical and allocative efficiency. Technical efficiency measures how well health inputs are converted into outputs, while allocative efficiency assesses whether resources are allocated in a way that maximises health benefits for the population (Nassar et al., 2020). HIM professionals are custodians of health data used to inform decisions and identify areas for improvement. By ensuring the accuracy and completeness of health data, they enable tailored interventions to improve safety and quality. Key performance indicators such as infection rates, hospital-acquired complications, and the number of serious events investigated are common measures used to determine how care is being delivered and to evaluate healthcare system performance (Lloyd et al., 2021).

Funding – Data-Driven Resource Allocation

In the context of data-driven resource allocation, HIM professionals are instrumental in the provision and use of data and analytics to inform budgeting and resource distribution decisions. Their expertise in the acquisition, classification, management, and analysis of health data ensures the efficient and effective allocation of resources to address the most pressing health needs (Health Information Management Association of Australia, 2025b). In Australia, clinical data and documentation play a crucial role in disease classification by ensuring accurate and comprehensive coding of patient diagnoses and treatments using the ICD-10-AM and ACHI system (Shepheard & Groom, 2020). Documentation underpins the Australian Refined Diagnosis Related Groups, which group patients with similar clinical conditions and resource usage, facilitating efficient hospital management and funding allocation (Shepheard & Groom, 2020).

Research – Data for Research, Scientific, and Clinical Advancements

HIM professionals are integral to supporting researchers in accessing health information for research (Shepheard & Groom, 2020). Data provides insights into disease patterns, treatment outcomes, and healthcare utilisation (Riley et al., 2024; Riley et al., 2023). HIM professionals’ expertise in managing large datasets and ensuring data quality is essential for conducting accurate and efficient research (Henderson et al., 2025). (Henderson et al., 2025) stated that recognition of research is important as a valuable professional development activity for the HIM profession.

Recent advancements in artificial intelligence (AI) and big data have the potential to significantly enhance the precision and efficiency of disease diagnosis, personalised medicine, and drug discovery (Mukhtar et al., 2024; Scott et al., 2021; Scott et al., 2024) . HIM professionals are integral to this process, as they manage the health data that AI systems learn from and analyse to identify trends and correlations. Their work supports the transformation of clinical trials by automating processes such as study screening, data extraction, and quality assessment.

Interoperability and Integration

HIM professionals play a critical role in ensuring interoperability across different health information systems to enable the seamless integration of healthcare information systems and data sharing across hospitals, clinics, and other healthcare facilities. By promoting the standardisation of data formats and ensuring compliance with frameworks such as HL7 FHIR, they overcome challenges related to data siloing. This enhances care coordination, allowing healthcare providers to access comprehensive patient data for timely, patient-centred care (Li et al., 2022). Initiatives such as openEHR (2024) provide a set of open specifications, clinical models, and software that integrate with software systems to standardise and improve interoperability.

Patient Empowerment and Engagement

HIM professionals work with clinicians and information technology specialists to facilitate patient empowerment by promoting access to health data through tools like patient portals (Dendere et al., 2019). Patient portals and mobile apps allow patients to monitor their health, manage chronic conditions, and actively participate in their care decisions, aligning with global trends in higher-income countries toward patient-centred care, fostering better health outcomes and stronger patient-provider relationships (Hägglund et al., 2022; Havana et al., 2023).

Information Governance, Privacy, and Security

With increasing digitisation, HIM professionals safeguard sensitive health data through ethical practice and by implementing and maintaining robust privacy and security frameworks (Henderson, 2021; Sher et al., 2017). Their expertise ensures compliance with privacy regulations while protecting against data breaches (Henderson, 2021). By prioritising data security, HIM professionals uphold patient trust and mitigate risks to patient safety, ensuring the ethical handling of health information (Rinehart-Thompson et al., 2009).

Information governance practices are designed to meet privacy and security requirements and ensure data integrity (Kwan et al., 2022). Information governance frameworks also embrace measures to manage health information and data from creation to disposal. Implementation complexity and costs have been described as major obstacles (Kwan et al., 2022). It is imperative that healthcare providers take preventive measures to minimise unauthorised access to patient information. Kwan et al (2022) emphasised the need for implementing robust privacy and security compliance, more audits (including for electronic records), and improved data management.

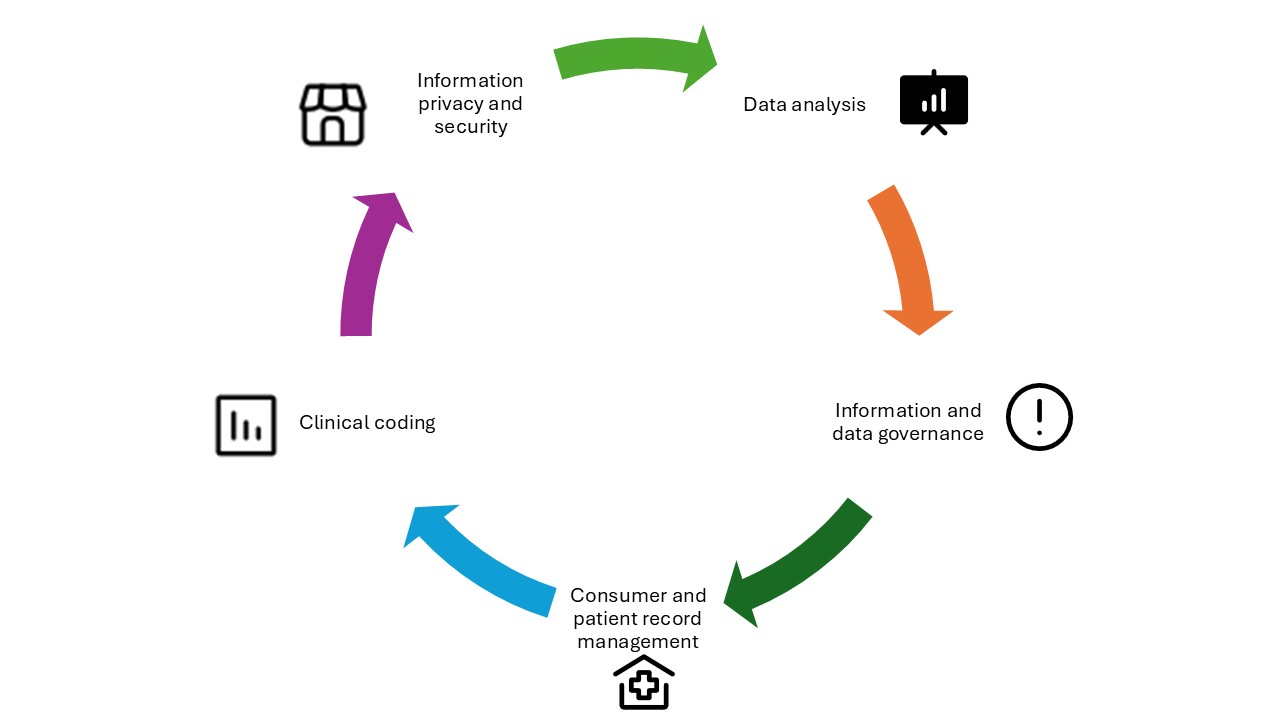

Policy Development and Advocacy

HIM professionals use health data insights to influence public health policies and healthcare reforms. Data shapes legislation, informs resource allocation, and can address disparities, ensuring interventions have a meaningful impact on population health (World Bank, 2023). HIM professionals act as advocates and advisors to ensure that policy decisions are based on accurate and actionable data. The International Federation of Health Information Management Associations (IFHIMA)—the international association for the HIM profession—has official relationships with the WHO, working in the field of health records and health information (IFHIMA, 2024). Health information managers play a key role in revising health classification systems. In Australia, health information managers are active advocates for standard definitions for principal diagnosis, the need for episodes of care to better reflect resource homogeneity, and improved data quality (Lloyd, 2023; Reid et al., 2000). The Figure below outlines HIM practices.

Source: Adapted from Figure 10.1 in Abdelhak & Haendel (2022). [Go to image description]

Health Information Management Contexts

HIM encompasses a spectrum of contexts, each with unique challenges and opportunities, from local healthcare facilities to regional and national networks, and even international exchanges.

Local/Care Provider Settings

This is the most immediate context, where health information is managed within a specific healthcare facility, such as a hospital, clinic, or primary care provider. The focus is on ensuring accurate, timely, and secure information for patient care within that setting.

Sharing With Other Healthcare Providers

This level involves the exchange of health information between different healthcare providers, such as between general practitioners, specialists, or allied health professionals. This is crucial for coordinated care where a consumer’s information needs to be accessible to all providers involved in their treatment.

In England, healthcare providers can access and share patient records across clinical systems via GP Connect—a NHS initiative to enable coordinated care (NHS, 2024).

Networked/Regional/State

At this level, health information management expands to cover a broader geographical area such as a health network or region. Information is shared across multiple facilities and providers within the network to support integrated care, reduce duplication of tests, and improve patient outcomes.

Operating as an integrated health system, Kaiser Permanente shares patient data across its 40 hospitals in the US, with a unified electronic health record that supports care coordination and reduces duplication of services (Kaiser Permanente Institute of Health Policy, 2024). Similarly, in Australia, NSW and Queensland state governments delivering hospital and community services have implemented electronic health record systems that allow a single instance of a patient’s record (NSW Health, 2023; Woods, Dendere, et al., 2023).

National

This involves the standardisation and sharing of health information across an entire country. National health information systems may be used for public health monitoring, national registries, or national EHRs, ensuring that data are consistent and accessible across the country.

The Danish National Patient Register, considered the largest collection of healthcare data internationally, contains comprehensive data on all medical examinations and treatments in Danish hospitals over the past 40 years, supporting public health monitoring and improving nationwide care delivery (Healthcare Denmark, 2023). In Australia, My Health Record, an opt-out system, holds summary health information for eligible citizens (Australian Digital Health Agency, 2024). The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare and the Australian Bureau of Statistics also hold data and statistics about the status of the population’s health, performance of the healthcare system and health workforce (Australian Institute of Health and Welfare, 2025a, 2025b)

International

At the international level, health information management involves the exchange of health data between countries. This can be important for global health initiatives, research, tracking of diseases, and ensuring continuity of care for patients who move between countries (World Health Organization, 2025). It requires adherence to international standards and protocols for data sharing, privacy, and security. The World Health Organization reports data on the burden of disease and mortality through the Global Health Observatory (World Health Organization, 2025).

The European Union has implemented a cross-border health data exchange framework through the eHealth digital service infrastructure that facilitates the sharing of health information with member nations, ensuring continuity of care for citizens travelling within the European Union (European Commission, 2024).

Reflective Activity – Exploring the Global Health Observatory

Instructions

- Visit the Global Health Observatory website [opens in new tab].

- Navigate through the main sections: indicators, countries, data API, map gallery, and publications.

- Spend at least 10 minutes exploring each section to understand the type of data and resources available.

Reflect on the following questions

- Data utilisation: How can the data available on the GHO website be utilised in your current role as a health information manager?

- Indicators: Identify three key health indicators relevant to your region or area of work. How can these indicators inform health policy and decision-making?

- Future applications: Consider a future project or initiative you are involved in. How can the GHO data support this project?

Write a short reflection

Summarise your findings and reflections in a short paragraph (200–300 words). Focus on how the GHO can enhance your work and any insights gained from exploring the website.

Forms of Health Information Management

Health information management (HIM) professionals in Australia play a vital role in the healthcare system by managing and safeguarding health information (Henderson, 2021). This includes organising, overseeing, and protecting data and ensuring that both traditional and digital data are accurate, accessible, and secure. HIM professionals are trained in information technology applications, often serving in roles that connect clinical, operational, and administrative functions (Health Information Management Association of Australia, 2025a).

The scope of practice for HIM professionals in Australia is diverse and can include tasks such as compiling, organising, maintaining, and protecting confidential records; designing health information systems to comply with medical, legal, and ethical standards; and entering and maintaining information in EMRs (Health Information Management Association of Australia, 2025b). They also monitor information in EMRs for accuracy; observe trends in audits and denials from payers; analyse clinical data for research, process improvement, reporting, and more.

HIM professionals work with various types of information, including:

- Patient health information – this encompasses symptoms, diagnoses, clinical and social histories, test results, and procedures

- Clinical information – this encompasses clinical investigation, diagnosis and treatment modalities and documentation such as referrals, letters and care summaries

- Safety information – this encompasses patient and clinical metrics against benchmarks and standards

- Patient administration information – this includes patient identification, contact and payment information

- Health system information – this includes booking, scheduling and activity information

HIM professionals in Australia find employment in a variety of settings, including hospitals, primary care, clinicians’ offices, cancer and population registries, pharmaceutical firms, insurance companies, software companies, residential aged care settings, government agencies such as the AIHW, and consulting firms.

Australian studies have found that graduate HIM professionals have high employability and utilise most or all of the specialised domains of professional knowledge and skills (Gjorgioski et al., 2025; Riley et al., 2020). These studies identified broad categories of position titles for health information managers, reflecting the foci of positions (Gjorgioski et al., 2025; Riley et al., 2020), as shown in Box 1 below.

- HIM focus: This category groups positions that have health information management as the role descriptor. It includes responsibilities such as the management of staff, records, and forms, Freedom of Information and patient/client access to information, patient admissions, and other administrative components of patient flow.

- Health classification, including financial focus: These positions identify health classification, colloquially termed “clinical coding”, as the major role. This also includes health insurance industry–based work involving health classification.

- Data management and analytics focus: The major activities here relate to the management, interpretation, analysis, and reporting of health data.

- Health information systems focus: This category groups positions where the role’s primary focus is information systems that manage health information; for example, systems administrator or implementation manager.

- Other foci: This category represents roles that do not fit into the above categories or incorporate several categories equally: for example, academic, project officer (non-ICT), or policy officer.

Source: Focus of Health Information Manager roles in Australia. Adapted from (Riley et al., 2020) Riley M, Robinson K, Prasad N, et al. Workforce survey of Australian graduate health information managers: Employability, employment, and knowledge and skills used in the workplace. Health Information Management Journal. 2020;49(2-3):88-98. doi:10.1177/1833358319839296

The Healthcare Record

Healthcare records are essential for documenting an individual’s clinical history, treatments, and outcomes. Their purpose is to facilitate communication among healthcare providers and support clinical decision-making. Healthcare records date back to ancient times, with the earliest known medical documentation found on Sumerian clay tablets (Dalianis, 2018; Gillum, 2013). In Ancient Egypt, Papyrus provided detailed medical recommendations dating back to 1550 BCE, (Dalianis, 2018; Gillum, 2013). The practice of keeping patient records evolved significantly with the contributions of the Greek physician Hippocrates. Medical records handwritten on paper posed challenges in terms of storage, accessibility, and data loss. The transition to digital systems began in the 1960s, with the advent of EMRs revolutionised patient care by enhancing efficiency, accuracy, and accessibility (Gillum, 2013). General practitioners, hospitals, residential aged care organisations, primary care providers and specialists all maintain healthcare records.

The Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care (2021) outlines that healthcare records should be available to healthcare providers at the point of care, support accurate and complete record-keeping, comply with privacy and security regulations, and facilitate patient access to their healthcare records. Healthcare records often share a similar composition worldwide (Lorkowski & Pokorski, 2022). In Australia, AS2828.1 and 2:2019 are the relevant Standards for health records (Standards Australia, 2019a, 2019b) and shown in the Box below.

AS2828.1:2019 specifies the requirements for the physical aspects of paper health records. This includes aspects such as size, quality, reproducibility, layout, colour, division, methods of fixing, and cover. The standard aims to ensure that paper health records are fit for purpose, easy to use, consistent, and meet legal, safety, and quality requirements. It also provides advice on the design of forms for incorporation into health records, covering areas such as health record forms, dividers, health record covers, filing, retention, and destruction.

AS2828.2:2019 focuses on the digitisation (scanning) of paper health records. This standard provides technical specifications, data capture, and implementation principles, as well as quality control measures. It also offers guidelines on best practices for the safe storage, security, conformance, and reproducibility of digitised health records. The main sections of AS2828.2:2019 include digitisation of health records, processes for digitisation, and digitising health record systems. This standard ensures that digitised health records maintain the integrity and accessibility required for effective healthcare delivery.

Source: Standards Australia AS2828.1:2019 [opens in new tab] and AS2828.2:2019 [opens in new tab]

Ownership of Healthcare Record

Ownership of healthcare records varies internationally and often involves a distinction between a physical or electronic record and the information it contains. Typically, the physical or electronic record is owned by the healthcare provider or the institution responsible for creating it. The information within the record is often considered the property of the consumer (McGuire et al., 2019). This dual ownership concept allows consumers the right to access their healthcare information, fostering transparency, and empowering consumers in their own care. These principles are mirrored in many healthcare systems; in Singapore, the National Electronic Health Record ensures healthcare records are accessible across both public and private health providers, giving consumers and providers a consolidated view of medical history (Ministry of Health Singapore, 2025). In the United Kingdom, the NHS App ensures consumers can view their healthcare records from their general practitioner (NHS, 2024). Similarly, Australians have a longitudinal health summary that can be personally controlled (Australian Digital Health Agency, 2024). The Australian Digital Health Agency acts as the system operator, managing the My Health Record system (Australian Government, 2012).

The Personally Controlled Healthcare Record

Australia’s My Health Record is a digital health record system that integrates data from various sources, including healthcare providers, to provide a summary of an individual’s health information (Australian Digital Health Agency, 2024). The components of My Health record include pathology and diagnostic imaging reports, prescription and dispensing information, hospital discharge summaries, allergies and adverse reactions, immunisation history and advance care planning. Individuals can also add their own information. Individuals with a My Health Record can personally control what is included and who can access their records. My Health Record is crucial for ensuring continuity of care as it provides healthcare professionals with the necessary information to make informed decisions about a patient’s treatment (Australian Digital Health Agency, 2024).

Global Challenges and Drivers of Change

The sustainability of a healthcare system is a critical concern in today’s world. Ensuring that healthcare systems can continue to provide high-quality care without depleting resources or causing environmental harm is paramount. This involves everyone, including health information professionals, adopting practices that reduce waste, improve efficiency, and promote the use of renewable resources. Technological advancements and digital transformation play a crucial role in achieving sustainability. For example, the implementation of EMRs/EHRs, telehealth, and other digital tools can streamline processes and reduce the environmental footprint of healthcare operations. This can be achieved through examples such as reductions in printing and improved flow of information.

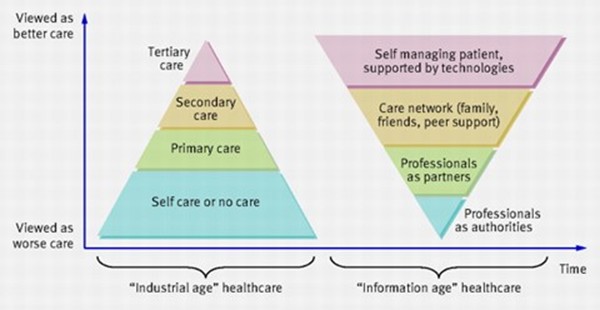

Patient and consumer-centred care is essential for safe, high quality health services, today and into the future. Greenhalgh et al., (2010) argued that traditional healthcare often involves top-down directives and large-scale projects, whereas modern digital health solutions need to closely align with patients’ attitudes, self-management practices, and identified information needs to be effective. This shift from industrial age healthcare to information age healthcare requires profound shifts in relationships and interactions between health and consumers as shown in the Figure below.

Big data and analytics have become indispensable in modern healthcare. Big data refers to the vast amounts of data generated in healthcare, including patient records, treatment outcomes, and operational data. Analytics involves using these data to gain insights and make informed decisions (Abdelhak & Haendel, 2022). AI and machine learning can transforming healthcare by enabling predictive analytics, personalised medicine, and improved patient outcomes. These technologies can analyse large datasets to identify patterns and trends that would be impossible for humans to detect (Scott et al., 2021; Scott et al., 2024). However, data interoperability is essential for effective big data analytics. While ensuring that different systems can communicate and share data seamlessly is a significant challenge, it is necessary for sharing and utilising the full potential of the data collected by healthcare organisations (Australian Digital Health Agency, 2023; Woods et al., 2024).

AI has the potential to revolutionise HIM by automating routine tasks, improving data accuracy, and enabling advanced analytics. AI applications in healthcare include clinical decision support, predictive analytics, personalised medicine, and administrative automation (Scott et al., 2021). Despite its potential, AI in healthcare also presents challenges, such as ensuring data privacy, addressing ethical concerns, and managing the integration of AI systems into existing workflows (Scott et al., 2021). Read chapter Navigating the Future to understand further the impacts of AI and Big data.

Achieving the Quintuple Aim (previously the Quadruple Aim) of health is a central goal in healthcare and digital health can help provide foundational data to monitor progress (Woods et al., 2023; Woods et al., 2024). The Aim focuses on improving patient experience, enhancing population health, reducing costs, and workforce well-being and safety, with a fifth aim of advancing health equity (Institute of Healthcare Improvement, 2022). Data play a critical role in achieving these goals. For example, data analytics can help identify areas for cost reduction, improve patient outcomes through personalised treatment plans, and enhance the overall efficiency of healthcare delivery (Canfell et al., as cited in (Almond & Mather, 2023). Real-time data exchange and interoperability are crucial to achieving the Quadruple Aim, requiring robust data governance, privacy protections, and collaboration between different healthcare entities. HIM professionals are integral to the success of the Quintuple Aim by ensuring effective data use to improve patient experience, enhance population health, reduce costs, and improve healthcare providers’ work lives.

Case Study – Blockchain Technology Transforming HIM

Bautista et al. (2023), working with an interdisciplinary team from the University of Texas at Austin, developed MediLinker, a blockchain-based decentralised health information platform, aiming to empower patients with greater control over their data and address interoperability and security issues.

The MediLinker platform provides a self-sovereign identity system that enables patients to manage and share their health information via digital wallets. Using the Hyperledger Indy blockchain framework, patients can securely store decentralised identifiers and verifiable credentials compliant with HL7 FHIR standards, enabling seamless data exchange across EHRs. Read MediLinker: A blockchain-based decentralized health information management platform for patient-centric healthcare [opens in new tab] for further insights on the role of blockchain and health information management.

Digital Front Door

Many healthcare organisations are working towards the “digital health front door”, which refers to using digital technologies to create a seamless and accessible entry point for individuals seeking healthcare services. It aims to provide patients with convenient access to a range of healthcare resources, information, and services through digital channels, such as websites, mobile apps, and telehealth platforms. The digital front door provides patients with greater access to their health information and enables them to play a more active role in their care.

Activity: Advantages of the Digital Health Front Door

Watch the below short video. Reflect on the advantages of the digital health front door for consumers and health providers.

Feedback

The advantages of the digital front door for health providers are a streamlined approach to processes such as appointment scheduling, patient registration, and billing, allowing healthcare providers to operate more efficiently. This frees up time and resources that can be allocated to direct patient care, enhancing productivity.

Digital health front doors empower patients to take a more active role in managing their health by providing them with access to their health information, educational resources, and self-care tools. This can enhance patient engagement, foster shared decision-making between patients and providers, and lead to better health outcomes.

Key Implications for Practice

Health information is essential for good health. Individuals can use health information to manage their health and control the factors that impact health. Accurate health information improves communication between patients and healthcare providers. Trusted, accessible, and reliable health information enables individuals and societies to lead healthier and more fulfilling lives.

The healthcare landscape is constantly changing as new technologies and regulations emerge. HIM professionals must be adaptable and open to continuous learning, the acquisition of new skills, and keep up to date with the core skills required for their work. The rapid transformation of digital health data, coupled with advances in technological capabilities, has led to an influx of new data sources such as wearable and remote monitoring devices, requiring HIM professionals to expand their skill sets. Expertise in data science, informatics, and governance is now essential to effectively manage and leverage these advancements.

Ensuring that HIM practices support patient-centred care is crucial. This includes facilitating patients’ access to their health records and ensuring data are used to improve patient outcomes. Effective data governance frameworks are essential to ensuring secure, accurate, and accessible data. This empowers patients to take control of their health and enables healthcare providers to make more informed decisions that enhance patient care.

The HIM profession is evolving beyond traditional roles in clinical coding and records management. HIM professionals are increasingly expected to take on responsibilities in data analytics, data stewardship, and leadership in information governance. These roles are pivotal to ensuring that health data are collected, analysed, and used to improve clinical outcomes and organisational decision-making.

As big data becomes more prevalent in healthcare, effective data governance and analytics are essential. HIM professionals must ensure the secure and efficient management of the large volumes of health information generated.

References

Abdelhak, M., & Haendel, A. (2022). The View of Health Information Managers (HIM): Strategic Insights Through Data Analytics. In U. H. Hübner, G. Mustata Wilson, T. S. Morawski, & M. J. Ball (Eds.), Nursing Informatics : A Health Informatics, Interprofessional and Global Perspective (pp. 111-120). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-91237-6_10

Almond, H., & Mather, C. (2023). Digital Health: A Transformative Approach. Elsevier Health Sciences.

Australian Digital Health Agency. (2023). National Digital Health Strategy 2023-2028. https://www.digitalhealth.gov.au/discover-the-national-digital-health-strategy-2023-2028

Australian Digital Health Agency. (2024). My Health Record. https://www.digitalhealth.gov.au/

My Health Record Act, (2012). https://www.legislation.gov.au/C2012A00063/latest/text

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2025a). Health Workforce. Australian Government. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/workforce/health-workforce

Australian Institute of Health and Welfare. (2025b). MeteOR The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare’s Metadata Online Registry. Australian Government. https://meteor.aihw.gov.au/content/181162

Bautista, J. R., Harrell, D. T., Hanson, L., De Oliveira, E., Abdul-Moheeth, M., Meyer, E. T., & Khurshid, A. (2023). MediLinker: a blockchain-based decentralized health information management platform for patient-centric healthcare. Frontiers in Big Data, 6. https://doi.org/10.3389/fdata.2023.1146023

Canadian Institute for Health Information. (2024). Health Information Management Professionals. https://www.cihi.ca/en/health-information-management-professionals#:~:text=Health%20information%20management%20(HIM)%20professionals,Health%20Workforce%20Database%20metadata%20page.

Chopra, A. (2024). A Research Study To Analyze The Economic Implications Of Government Policies On Singapore’s Residents, And To Propose Recommendations To These Policies.

Commonwealth Fund. (2024). Mirror, Mirror 2024. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/fund-reports/2024/sep/mirror-mirror-2024

Dalianis, H. (2018). The History of the Patient Record and the Paper Record. In H. Dalianis (Ed.), Clinical Text Mining: Secondary Use of Electronic Patient Records (pp. 5-12). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-78503-5_2

Dendere, R., Slade, C., Burton-Jones, A., Sullivan, C., Staib, A., & Janda, M. (2019). Patient Portals Facilitating Engagement With Inpatient Electronic Medical Records: A Systematic Review. J Med Internet Res, 21(4), e12779. https://doi.org/10.2196/12779

European Commission. (2024). Electronic cross-border health services. https://health.ec.europa.eu/ehealth-digital-health-and-care/electronic-cross-border-health-services_en

Gillum, R. F. (2013). From papyrus to the electronic tablet: a brief history of the clinical medical record with lessons for the digital age. The American journal of medicine, 126(10), 853-857. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjmed.2013.03.024

Gjorgioski, S., Riley, M., Lee, J., Prasad, N., Tassos, M., Nexhip, A., Richardson, S., & Robinson, K. (2025). Workforce survey of Australian health information management graduates, 2017-2021: A 5-year follow-on study. Health Inf Manag, 54(1), 43-54. https://doi.org/10.1177/18333583231197936

Greenhalgh, T., Hinder, S., Stramer, K., Bratan, T., & Russell, J. (2010). Adoption, non-adoption, and abandonment of a personal electronic health record: case study of HealthSpace. Bmj, 341.

Hägglund, M., McMillan, B., Whittaker, R., & Blease, C. (2022). Patient empowerment through online access to health records. BMJ, e071531. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj-2022-071531

Hanson, R. M. (2011). Good health information–an asset not a burden!. Australian Health Review, 35(1), 9-13.

Hardy, L. R. (2024). Health informatics: An interprofessional approach (3rd ed.). Elsevier Health Sciences.

Harris, B., & Cresswell, R. (2024). The legacy of voluntarism: Charitable funding in the early NHS. The Economic History Review, 77(2), 554-583. https://doi.org/10.1111/ehr.13280

Havana, T., Kuha, S., Laukka, E., & Kanste, O. (2023). Patients’ experiences of patient-centred care in hospital setting: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Scand J Caring Sci, 37(4), 1001-1015. https://doi.org/10.1111/scs.13174

Health Foundation. (2019). Building healthier communities: the role of the NHS as an anchor institution. https://www.health.org.uk/reports-and-analysis/reports/building-healthier-communities-the-role-of-the-nhs-as-an-anchor

Health Information Management Association of Australia. (2025a). Health Information Management Professionals. https://www.himaa.org.au/about-himaa/about-himaa/

Health Information Management Association of Australia. (2025b). HIMAA Health Information Management Profession Identity Statement. https://www.himaa.org.au/public/169/files/Website%20Document/Our%20Work/Advocacy/HIMAA%20Health%20Information%20Management%20Profession%20Identity%20Statement%20v1_0.pdf

Health Information Management Association of Australia (HIMAA). (2024). Consultation Paper – Professional Identity of the Health Information Profession.

Healthcare Denmark. (2023). Collection and sharing of health data. https://healthcaredenmark.dk/national-strongholds/digitalisation/collection-and-sharing-of-health-data/

Henderson, J. (2021). Patient privacy in the COVID-19 era: Data access, transparency, rights, regulation and the case for retaining the status quo. Health Inf Manag, 50(1-2), 6-8. https://doi.org/10.1177/1833358320966689

Henderson, J., Riley, M., Brown, B., Lam, M., Gjorgioski, S., Tassos, M., Davis, J., & Robinson, K. (2025). Health information management professionals’ investigator involvement in research: barriers and facilitators. Health Inf Manag, 18333583251322985. https://doi.org/10.1177/18333583251322985

IFHIMA. (2024). FHIMA & the World Health Organization (WHO). 2024. https://ifhima.org/publication-resources/who/

Institute of Healthcare Improvement. (2022). On the Quintuple Aim: Why Expand Beyond the Triple Aim? Retrieved 1/3/24 from On the Quintuple Aim: Why Expand Beyond the Triple Aim?

Kaiser Permanente Institute of Health Policy. (2024). Integrated Care Stories: An Overview of Our Integrated Care Model. https://www.kpihp.org/integrated-care-stories/overview/

Kemp, T., Fernandes, L., Barnes, C., Marshall, D., Burns, M., Mandapam, S. K., Hatta, G., Kim, O., & Butler-Henderson, K. (2021). Working as a Health Information Manager. In K. Butler-Henderson, K. Day, & K. Gray (Eds.), The Health Information Workforce : Current and Future Developments (pp. 269-280). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-81850-0_18

Kwan, H., Riley, M., Prasad, N., & Robinson, K. (2022). An investigation of the status and maturity of hospitals’ health information governance in Victoria, Australia. Health Inf Manag, 51(2), 89-97. https://doi.org/10.1177/1833358320938309

Li, E., Clarke, J., Ashrafian, H., Darzi, A., & Neves, A. L. (2022). The Impact of Electronic Health Record Interoperability on Safety and Quality of Care in High-Income Countries: Systematic Review. J Med Internet Res, 24(9), e38144. https://doi.org/10.2196/38144

Lloyd, S. (2023). Health information management leadership in activity based funding: the past, present and future.

Lloyd, S., Cliff, C., FitzGerald, G., & Collie, J. (2021). Can publicly reported data be used to understand performance in an Australian rural hospital? Health Inf Manag, 50(1-2), 35-46. https://doi.org/10.1177/1833358320948559

Lorkowski, J., & Pokorski, M. (2022). Medical Records: A Historical Narrative. Biomedicines, 10(10). https://doi.org/10.3390/biomedicines10102594

Maulana, N., Soewondo, P., Adani, N., Limasalle, P., & Pattnaik, A. (2022). How Jaminan Kesehatan Nasional (JKN) coverage influences out-of-pocket (OOP) payments by vulnerable populations in Indonesia. PLOS Global Public Health, 2(7), e0000203. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pgph.0000203

McGuire, A. L., Roberts, J., Aas, S., & Evans, B. J. (2019). Who Owns the Data in a Medical Information Commons? Journal of Law, Medicine & Ethics, 47(1), 62-69. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073110519840485

Ministry of Health Singapore. (2025). Health Information and the NEHR. Retrieved 11/112/2024 from https://www.healthinfo.gov.sg/overview/health-info-and-nehr/

Mukhtar, S. A., McFadden, B. R., Islam, M. T., Zhang, Q. Y., Alvandi, E., Blatchford, P., Maybury, S., Blakey, J., Yeoh, P., & McMullen, B. C. (2024). Predictive analytics for early detection of hospital-acquired complications: An artificial intelligence approach. Health Information Management Journal. https://doi.org/10.1177/18333583241256048

Nassar, H., Sakr, H., Ezzat, A., & Fikry, P. (2020). Technical efficiency of health-care systems in selected middle-income countries: an empirical investigation. Review of Economics and Political Science, 5(4), 267-287. https://doi.org/10.1108/reps-03-2020-0038

NHS. (2024). GP Connect. https://digital.nhs.uk/services/gp-connect

NSW Health. (2023). Contract signed for the Single Digital Patient Record. https://www.ehealth.nsw.gov.au/news/2023/sdpr-contract-signed

Reid, B., Palmer, G., & Aisbett, C. (2000). The performance of Australian DRGs. Australian Health Review, 23(2), 20-31.

Riley, M., Lee, J., Richardson, S., Gjorgioski, S., & Robinson, K. (2024). The applications of Australian-coded ICD-10 and ICD-10-AM data in research: A scoping review of the literature. Health Inf Manag, 53(1), 41-50. https://doi.org/10.1177/18333583231198592

Riley, M., Robinson, K., Kilkenny, M. F., & Leggat, S. G. (2023). The suitability of government health information assets for secondary use in research: A fit-for-purpose analysis. Health Inf Manag, 52(3), 157-166. https://doi.org/10.1177/18333583221078377

Riley, M., Robinson, K., Prasad, N., Gleeson, B., Barker, E., Wollersheim, D., & Price, J. (2020). Workforce survey of Australian graduate health information managers: Employability, employment, and knowledge and skills used in the workplace. Health Information Management Journal, 49(2-3), 88-98.

Rinehart-Thompson, L. A., Hjort, B. M., & Cassidy, B. S. (2009). Redefining the health information management privacy and security role. Perspect Health Inf Manag, 6(Summer), 1d.

Scott, I. A., Abdel-Hafez, A., Barras, M., & Canaris, S. (2021). What is needed to mainstream artificial intelligence in health care? Aust Health Rev, 45, 591-596. https://doi.org/10.1071/AH21034

Scott, I. A., van der Vegt, A., Lane, P., McPhail, S., & Magrabi, F. (2024). Achieving large-scale clinician adoption of AI-enabled decision support. BMJ Health Care Inform, 31(1). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjhci-2023-100971

Shepheard, J., & Groom, A. (2020). The role of health classifications in health information management. Health Inf Manag, 49(2-3), 83-87. https://doi.org/10.1177/1833358320905970

Sher, M. L., Talley, P. C., Cheng, T. J., & Kuo, K. M. (2017). How can hospitals better protect the privacy of electronic medical records? Perspectives from staff members of health information management departments. Health Inf Manag, 46(2), 87-95. https://doi.org/10.1177/1833358316671264

Standards Australia. (2019a). Health records, Part 1: Paper health records. In. Australia: HE-025 (Health Records).

Standards Australia. (2019b). Health records, Part 2: Digitized health records. In. Australia: HE-025 (Health Records).

Stukus, D. (2019). Impact of “eHealth” in allergic diseases and allergic patients. J Investig Allergol Clin Immunol, 29(2), 94-102.

UHC2030. (2024). A global health financing emergency threatens progress toward universal health coverage. Retrieved 10/1/2024 from https://www.uhc2030.org/

Van Calster, B., Wynants, L., Timmerman, D., Steyerberg, E. W., & Collins, G. S. (2019). Predictive analytics in health care: how can we know it works? Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 26(12), 1651-1654. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocz130

Woods, L., Canfell, O., & Sullivan, C. (2023). Applied Clinical Informatics. In H. Almond & C. Mather (Eds.), Digital Health: A Transformative Approach. Elsevier Health Sciences.

Woods, L., Dendere, R., Eden, R., Grantham, B., Krivit, J., Pearce, A., McNeil, K., Green, D., & Sullivan, C. (2023). Perceived impact of digital health maturity on patient experience, population health, health care costs, and provider experience: mixed methods case study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 25, e45868.

Woods, L., Eden, R., Canfell, O., Nguyen, K. H., Comans, T., & Sullivan, C. (2023). Show me the money: how do we justify spending health care dollars on digital health? Med J Aust, 218(2), 53-57. https://doi.org/10.5694/mja2.51799

Woods, L., Eden, R., Green, D., Pearce, A., Donovan, R., McNeil, K., & Sullivan, C. (2024). Impact of digital health on the quadruple aims of healthcare: A correlational and longitudinal study (Digimat Study). Int J Med Inform, 189, 105528. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2024.105528

World Bank. (2023). Digital in Health: Unlocking the Value for Everyone. https://www.worldbank.org/en/topic/health/publication/digital-in-health-unlocking-the-value-for-everyone

World Health Organization. Social Determinants of Health. https://www.who.int/health-topics/social-determinants-of-health#tab=tab_1

World Health Organization. (2021a). Global strategy on digital health 2020-2025.

World Health Organization. (2021b). WHOs 7 Policy Recommendations on Building Resilient Healthcare Systems. https://www.who.int/news/item/19-10-2021-who-s-7-policy-recommendations-on-building-resilient-health-systems

World Health Organization. (2025). Global Health Observatory. https://www.who.int/data/gho

Image descriptions

Figure 1: A circular diagram showing Health Information Management Practices as a process flow consisting of five segments. Each segment indicates a different area of focus in health information management, visually interconnected by the circle. Data Analysis begins at the top, then moves clockwise to Information and Data Governance, followed by Consumer and Patient Record Management, then moving to Information Privacy and Security, and finally Clinical Coding.

Figure 2: The image features two pyramids set side by side. The left pyramid is oriented with the base at the bottom, labeled as “Industrial age” healthcare. It is divided into four sections from bottom to top: “Self care or no care,” “Primary care,” “Secondary care,” and “Tertiary care.” The right pyramid is inverted, labeled as “Information age” healthcare. This pyramid is also divided into sections from bottom to top: “Professionals as partners,” “Care network (family, friends, peer support),” and “Self managing patient, supported by technologies.” Arrows at the top and left sides of the image indicate that time progresses from left to right and that the care is viewed as better at the top of the pyramids and worse at the bottom.