Chapter 1 – Introduction to Finance

Chapter Learning Objectives

After completing this chapter, students should be able to

- Define what finance is about

- Define the corporate objective in relation to maximising the wealth of shareholders

- Understand the different corporate financial decisions and their impacts on the firms value

- Define the different legal form of business organisation and compare the three typical forms of business

- Identify the advantages and disadvantages of each type of business structure

-

What is Finance?

Finance is concerned with the allocation and distribution of monetary capital and risks amongst various entities. It is an area of study that delves into how individuals, businesses, and institutions value, obtain, and manage their financial resources. Finance can be divided into four broad categories: Corporate Finance, Investments, Financial Markets and Institutions and Personal Finance. Let’s explore each of these four areas of Finance:

- Corporate Finance is the study of how corporations make financial decisions in order to maximise their shareholders wealth. Essentially, corporate finance is about how corporations invest in real assets which generate income, how these assets are funded and how the income is distributed to shareholders.

- Investments is the field that examines how individuals and managers allocate their assets over time under conditions of certainty and uncertainty. The goal of investments not only aim to maximise returns but do so in a manner that is consistent with the investor’s objectives and tolerance for risk. The investment process often involves valuations, risk and returns analysis, constructing and evaluating portfolio performance.

- Financial Markets and Financial Institutions is the study that focuses on understanding how financial markets operate, the various types of financial instruments that are traded, the structure and functioning of financial institutions and how they all contribute to the broader financial system.

- Personal Finance is a field that examines the financial decisions of an individual or a household. This includes retirement planning, insurance, saving, insurance, tax planning and estate planning. Personal finance involves continuous learning and adjustment to adapt to life changes, economic shifts and individual circumstances.

-

Why study Finance?

Whether your aim is to land a high paying finance careers or not, finance provides you powerful tools to understand and navigate the interplay of market conditions and economic forces. Studying finance is not just about managing money but it is about making critical decisions in a world full of uncertainties. For example, you have probably heard the phrase “There is nothing such as a Free Lunch”. So, in order to earn a return, you have to take some risk. The more risks you take, the higher returns you earn. Finance tells you that not all risks are counted as equal. Some risks will enable you to achieve higher returns, others will not. What about maybe there is a “free” lunch i.e. investment opportunities that offer high returns but very low or no risks. Are these opportunities real? What is their chance of happening or repeating in the future? What about legendary investors such as Warren Buffet, Jim Simons or Peter Thiel? Are they lucky? Do they take higher risks and what risks do they take? What investment strategies do they follow? Finance offers essential insights that help you addressing these questions.

-

How are businesses are formed?

In Australia, in order to operate a business, you need to decide on its structure. Each structure has certain advantages and disadvantages. The most suitable structure for your business should be based on its scale and nature, as well as your preferred management style. When starting or expanding your business, you have the option to select from four fundamental structures:

- A sole trader is a business structure that is known for its simplicity in setup and operations, offering complete control over assets and business choices. It benefits from minimal reporting obligations and is typically a cost-effective model. Sole traders can file tax returns using their personal tax file number (TFN). However, this structure carries the disadvantage of unlimited liability, meaning personal assets could be at risk if the business faces financial difficulties. Additionally, sole traders are personally responsible for paying tax on all income earned from the business.

- A partnership is a business structure in which two or more individuals manage and operate a business in accordance with the terms and objectives set out in a Partnership Deed. The income or losses are shared among the partners according to the partnership deed.

The partnership business structure is also known for its ease of establishment and cost-efficiency, often involving less complexity compared to forming a corporation. When forming a partnership, it is necessary to obtain a separate Tax File Number (TFN) for the entity, which is used for all tax-related matters. Additionally, partnerships must acquire an Australian Business Number (ABN) and utilize it in all their business dealings. The partnership itself is not subject to income tax. Instead, the tax responsibility is passed on to the individual partners, who each pay tax on their proportion of the net income generated by the partnership. Finally, if the business’s turnover reaches or exceeds $75,000, the partnership must register for the Goods and Services Tax (GST). This structure allows individuals to pool their resources and expertise but also necessitates a high level of mutual trust and clear communication due to the joint responsibility for the partnership’s commitments. There are three principal forms of partnership:

- General Partnership (GP): In this arrangement, all partners participate in the day-to-day management of the business and each partner has joint liability for the debts and obligations of the business. This means that each partner is individually responsible, as well as collectively with other partners, for the liabilities of the partnership.

- Limited Partnership (LP): This form of partnership consists of both general and limited partners. The general partners manage the business and have unlimited liability for its debts, while the limited partners contribute capital and share in the profits but typically do not participate in managing the business. Limited partners’ liability is restricted to the amount they have invested in the partnership.

- Incorporated Limited Partnership (ILP): This form of partnership consists of both general and limited partners. The general partners manage the business and have unlimited liability for its debts, while the limited partners contribute capital and share in the profits but typically do not participate in managing the business. Limited partners’ liability is restricted to the amount they have invested in the partnership.

- A company is a form of a business structure where it is recognized as an independent legal entity, distinct from its owners or members, setting it apart from sole trader or partnership structures. Functioning much like an individual, a company is capable of incurring debt, initiating legal action, or being subject to legal claims. Shareholders of a company are typically not personally accountable for the company’s financial liabilities. Their main financial responsibility is limited to paying any amount that may be outstanding on their shares if such a payment is requested. However, it’s important to note that the company’s directors can face personal liability if they do not fulfill their legal duties. Setting up a company can be a complex and costly endeavour. It is generally more suited to those who anticipate fluctuating business income and may benefit from the ability to carry forward losses to offset future profits. This structure is often favoured by those seeking to reinvest earnings into the business or plan for a long-term investment, due to the protections and potential tax advantages it can offer. If the company’s turnover reaches or exceeds $75,000, you are required to register for the Goods and Services Tax (GST). Non-profit organizations have a higher threshold set at $150,000 for GST registration.

- A trust is a structure where a trustee carries out the business on behalf of the trust’s members (or beneficiaries). In a trust structure, the trustee, who may be an individual or a company, holds and manages the business for the benefit of other parties, known as beneficiaries. This trustee bears full responsibility for all aspects of the trust, including both its income and any losses. Setting up a trust structure is typically costly and complex, often chosen to safeguard business assets for the beneficiaries’ advantage. The trustee is charged with the decision-making regarding the distribution of business profits among the beneficiaries. Due to the intricate nature of trusts, establishing one requires significant time, expertise, and careful planning.

The following diagram summarises the key differences between business structures:

| Sole trader | Partnership | Company | Trust | |

| Cost | Low | Medium | Medium to high | High |

| Complexity of setting up | Simple | Moderate | Complex | Highly complex |

| Tax obligations | Low | Low | Medium | High |

| Legal obligations | Low | Low to medium | High | Medium |

| Owner | You | You and your partners | Company shareholders | Trustee |

| Responsibility for business decisions | You | You and your partners share | The director(s) | Trustee |

| Responsibility for debts or losses | You | You and your partners share | Generally, the company | Trustee |

| Separate bank account needed | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Extra administration and reporting | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

Choose your business structure by business.gov.au used under CC-BY 3.0 Australia

-

What is the objective of a corporation?

Shareholders want managers to maximise the market value of the firm. A smart and effective manager makes decision that increase the current value of the company’s shares, thereby enhancing the wealth of its shareholders. This is known as the principle of shareholder wealth maximisation.

4.1 How do we measure the value of the firm?

There are various methods for valuing a corporation. One of the most common and straightforward approaches is to calculate the firm’s market capitalisation. This is done by multiplying the current share price of the company by its total number of outstanding shares.

This can be calculated using online share market data from sites such as Yahoo Finance. Using data from here, on on 8/01/2023 the market capitalization of Telstra can be calculated as: 3.9050 * 11.55 (billion) = 45.1 billion dollars. Have a look at todays data to see how Telstra’s market capitalisation has changed.

There are other methods to measure a company’s value, such as using revenue multiples, earnings multiples, or more complex valuation techniques like discounted cash flow analysis. Each method has its own advantages and is suitable for different types of analysis or investment decisions. The choice of valuation method can depend on the nature of the company’s business, the availability of financial data, and the specific goals of the valuation.

4.2 Is maximising the value of the firm equivalent to maximising profit?

Maximising the value of a firm and maximising profit are related but not equivalent. Profit is not cash and maximising profit refers to the short-term goal of increasing a company’s earnings or profits. It involves strategies to enhance revenue and reduce costs without consideration the risks to future cash flows by doing so.

Maximising the value of the firm is a broader and more long-term objective. It involves increasing the overall worth of the firm to its shareholders, which encompasses not just current profits but the future cash flows and its associated risks. This approach considers factors like market expansion, innovation, customer loyalty, and brand strength.

In essence, while maximising profit is about making the most money in the short term, maximising the value of the firm is about increasing the overall worth of the business in the long run. The latter includes building sustainable business models, investing in growth opportunities, managing risks effectively, and maintaining a strong reputation, all of which contribute to long-term shareholder value.

4.3 Do managers always maximise the value of the firm and act in the best interests of shareholders?

While managers are expected to act in the best interest of shareholders by maximising the value of the firm, they may not always do so. This discrepancy leads to what is known as agency problems. Agency problems arise when there is a conflict of interest between the needs of the principal (in this case, the shareholders) and the agents (the managers). Since managers are hired to run the company on behalf of the shareholders, their decisions should align with the shareholders’ interest in maximising firm value. However, this alignment does not always happen due to several reasons:

- Divergence of goals: Managers may have personal goals that differ from the goal of shareholder wealth maximization. For instance, they might be more interested in expanding the company size to enhance their personal power and status, even if it’s not in the best financial interest of the shareholders.

- Risk Preferences: Shareholders typically have diversified portfolios and may prefer riskier strategies that promise higher returns, while managers, whose personal wealth (like stock options, job security) is tied to the company, may prefer safer, less profitable strategies.

- Short-Term Focus: Managers might focus on short-term achievements to enhance their reputation or achieve short-term performance targets, while shareholders generally benefit more from long-term strategic planning and investments.

To mitigate these agency problems, various mechanisms can be employed:

- Performance based incentives: Aligning managers’ compensation with shareholder interests, such as granting stock options or bonuses tied to company performance, can encourage managers to work towards maximizing shareholder value.

- Corporate Governance: Effective governance structures, including a strong, independent board of directors, can oversee and limit managerial actions that do not align with shareholder interests.

- Market Discipline: The threat of takeover or shareholder activism can also serve as a check on managerial decisions.

- Regulatory Oversight: Regulations and legal frameworks can set standards for managerial behaviour and protect shareholder rights.

4.4. Does the pursuit of increasing a corporation’s shareholder wealth conflict with social objectives?

Maximising the value of the firm and pursuing social objectives can sometimes appear to be in conflict, but actually, they are complementary. Traditionally, maximising shareholder value often focuses primarily on financial returns. This perspective can lead to a perceived conflict with social objectives, as actions beneficial for short-term profits may not align with social or environmental well-being. For example, cost-cutting measures might increase profits but could also lead to reduced workforce welfare or environmental harm.

A more modern approach integrates social objectives into the definition of corporate objective. This perspective, often associated with the concept of Corporate Social Responsibility (CSR) and Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) criteria, argues that addressing social and environmental issues can be beneficial for long-term corporate objective. Sustainable practices can enhance a company’s reputation, improve stakeholder relations, and mitigate risks associated with social and environmental issues, thereby potentially increasing long-term shareholder value.

The stakeholder theory posits that companies should serve not only their shareholders but all stakeholders, including employees, customers, and the community. By addressing the needs and concerns of a broader group, companies can build a more sustainable and ethical business model that, in the long term, can also maximise shareholder value. In summary, short-term profit maximization can conflict with social objectives, but in the long term, integrating social goals may be essential for sustainable profitability and resilience.

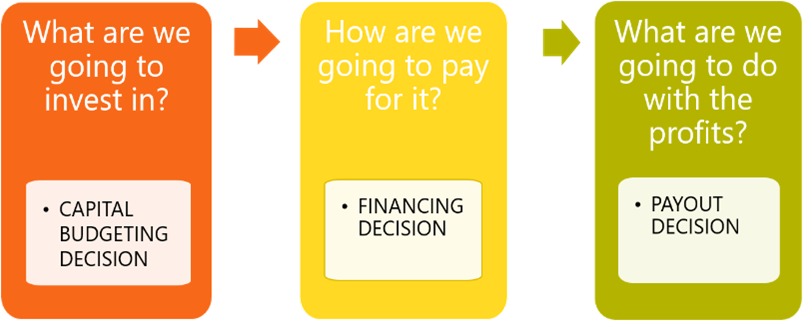

4.5 What are the key decisions made by managers to maximise the value of the firm and hence the wealth of its shareholders’?

Managers maximise the firm’s value by making a number of key corporate policies. These decisions are considered as key corporate policies because each of them has a direct impact on the firm’s value.

The BIG THREE

- Investment decisions

The investment decision sometimes is referred to as the capital budgeting or capital expenditure (CAPEX). It involves the acquisition, management and disposal of real assets. Real assets are assets that produce cash flows for a corporation through their productive use. These include tangible items like oil fields, land, and factories. Additionally, corporations invest in intangible assets such as research and development (R&D), advertising, and the development of computer software. These expenditures are considered investments because they contribute to the development of know-how, brand recognition, and reputation.

- Financing decisions

To finance its investments, a corporation can obtain funds either from lenders or from shareholders. When borrowing, the corporation receives cash from lenders and commits to repaying the debt along with interest. If shareholders provide the funding, they are not guaranteed a specific return; instead, they receive any future dividends the company may distribute. The decision of choosing between debt and equity financing is referred to as the capital structure decision. The term “capital” denotes the firm’s sources of long-term financing.

- Payout decisions

Some companies pay dividends to their shareholders, others do not. Payout policy answer a series of questions: “Should the company pay cash to its shareholders, how much and what are the mechanisms a corporation can use to distribute cash to its shareholders”. Corporations pay out cash by distributing dividends or by buying back some of their outstanding shares. Cash rich companies are more inclined to pay dividends whereas growth-oriented companies, often without a history of dividend payments are less likely to initiate such payouts in the near future.

Takeaways and looking ahead

In the first chapter, we delve into on what finance is, why it is important and perhaps interesting at the same time. We start to embark on a journey of someone who is contemplating to open a business and having to decide on the best structure for his/her business. We also explore the corporate objectives. Given manager’s goal is to maximise the value of the company and hence the wealth of their shareholder, do they always do so? Is the value maximization objective contradicting with the social objectives and what are the key corporate decisions that will exert a significant influence on the company’s value. In the next, chapter, we will examine the concept of Valuations i.e. the time value of money, present and future value.

References:

Support for businesses in Australia | business.gov.au

Graham, J., Smart, S. B., Adam, C., Gunasingham, B. Introduction to Corporate Finance (2nd Asia – Pacific Edition) 2017.

Brealey, R., Myers S. C., Allen F., Edmans, A. Principles of Corporate Finance (14th Edition) 2022.

Peirson, G., Brown, R., Easton, S., Howard, P., Pinder, S. Business Finance (12th Edition) 2015.