2.0 Digital health workforce and systems transformation

Tracy Parrish; Sharon Bourke; and Jenny Davis

The digitalisation of health care has transformed the workforce by improving efficiency, collaboration and productivity. Healthcare professionals are now required to be proficient in using various digital tools such as electronic medical records, artificial intelligence and telemedicine platforms to deliver quality patient care. This digital change has reshaped roles and responsibilities allowing nurses and midwives to spend more time on direct patient care. Thus, streamlining the way we deliver health care to enhance patient and population outcomes, including for First Nations people, in rural settings, underpinned by principles of diversity and inclusion.

Nurses and midwives play a crucial role in the successful transformation of digital health systems, leveraging competencies in technology integration, data analytics, telemedicine and digital health tools to improve patient care and ensure adoption of innovative healthcare solutions across diverse settings.

This chapter identifies the enablers and challenges of digital health and describes how nurses and midwives can implement strategies to support changes in digital health in the current and future climates of a digitalised workforce. The chapter begins by describing a digital health workforce, including nurses and midwives as clinical informaticians. It then examines capability frameworks and digital health systems applications in health care, current applications, facilitators and barriers to implementing digital health and strategies to support a digitalised healthcare workforce. The chapter concludes by identifying future directions and ongoing professional development for digitally capable nurses and midwives.

Learning outcomes

By the end of the chapter you will be able to:

- Describe what is meant by a digitally capable health workforce.

- Identify the different roles of nurses and midwives as part of the digital health workforce.

- Identify current digital health workforce frameworks.

- Describe what is meant by systems transformation.

- Identify examples of digital health system applications in healthcare settings.

- Describe implementation strategies for digital health.

- Examine challenges with digital health systems implementation.

- Identify strategies to support a digitally capable workforce.

- Describe ongoing professional development for a digitally capable nurse or midwife.

Framing questions

- What are the key digital workforce requirements to support health system applications?

- Where are nurses and midwives situated as clinical informaticians within the digital healthcare workforce?

- What are key enablers and challenges to systems transformation? (e.g. individual, workforce, system, process)

- How can barriers to systems transformation be addressed? (e.g. strategies at individual, policy and education levels)

- What are the key strategies to support a digitally capable workforce?

- How can digital health support person-centred care?

1. What is the digital health workforce?

Different definitions of the digital health workforce exist in the literature. It has been suggested that:

the (specialist) digital health workforce … possess the requisite skills and expertise to manage and govern the safe use of digital health tools and technologies. (Ryan et al., 2021, p. 201)

The broad healthcare workforce itself includes clinicians, system analysts, engineers, programmers, web-application developers, enterprise architects, integration specialists, data scientists, health informaticians, health information managers, health economists and cyber analysts (Lloyd et al., 2023). Increasingly, they all must be able to use digital technologies regardless of their role and specialised skills.

The necessary technical, cognitive and behavioural skills for a digitally enabled workforce identified by Lloyd et al. (2023) include:

- confidence in the use of technologies and systems to capture data and present, interpret and share information

- the ability to apply data science techniques to enable evidence-based decision-making and informed planning

- knowledge of information governance and security

- the ability to work with vendors and specify requirements for systems that can support workflow management and support the interdisciplinary team and consumers of health care.

In addition, the digital health workforce should have business skills required to create the case for technologies and identify technology benefits (Australian Digital Health Agency, 2020; Australian Institute of Digital Health, 2022).

However, it can be overwhelming keeping up with the rapid expansion of digital tools and applications, variously known as virtual technologies, medical applications, eHealth and mobile health tools, digitised health records, patient portals, clinical decision support systems, and personalised and predictive modelling technologies (Lawrence & Levine, 2024, p. 1).

1.1 Roles, careers and endless opportunities

Exciting new roles continue to emerge in digital health, including in clinical or health informatics. The terms health informatics and clinical informatics are often used interchangeably. Clinical informaticians are clinicians with specialised knowledge, skills and credentials in the application of informatics concepts, methods, tools and information technology to support the safe and effective delivery of health care (Davies et al., 2021; Valenta et al., 2017).

Activity

The Digital Health Hub by the Australasian Institute of Digital Health (AIDH) is a place where you can explore your digital health literacy, increase your knowledge and understand the next steps in your digital health career journey. Follow each of the links to see what the hub can do for you:

- Complete a self-assessment: evaluate your existing level of competence in digital health

- Increase my knowledge: discover initiatives spanning industry, education and government

- Map my career pathway: explore career pathways to help you on your digital transformation journey

- Track my progress: review your assessment results and update your profile.

The digital health workforce, then, can broadly be considered as those working in healthcare settings who, as part of their roles, actively engage in the use of information and communication technologies (ICT) to support the delivery of health care. Healthcare ICT includes digital health and eHealth systems and applications. These are discussed in Section 2.

Development of digital health competencies and capabilities within the workforce is critical for digital transformation and sustainable systems of health care. The qualities and capabilities of a digitally enabled workforce include systems thinking, technical proficiency, data analytics and more.

Digital competence is essential not just for health professions. The digital health future involves health service delivery and care models that emphasise consumer and patient experience, enabled by digital health (Australian Institute of Digital Health, 2023).

Digital transformation in health care refers to the integration of digital technologies into all aspects of health care delivery, management and operations. This includes the adoption of electronic medical records (EMR), telemedicine (which can also be referred to as telehealth, telenursing or telemidwifery), health data analytics, artificial intelligence (AI), wearable health devices and other digital tools to enhance patient care, improve operational efficiency and support informed decision-making (Stoumpos et al., 2023).

Digital transformation and implementation will impact the current and future health workforce, clinical workflows and education, yet the workforce is considered largely unprepared in areas including digital skills, telehealth, virtual care and strategies to keep up with existing and emerging technologies (Morris et al., 2023).

Activity

Explore the AIDH website. This body represents a diverse and growing community of professionals at the intersection of health care and technology.

1.2 Current digital health workforce frameworks

This section examines some of the frameworks that inform our understandings of digital health workforce capability and competency elements, including core knowledge, skills, attitudes and education.

The World Health Organization (WHO) defines digital health as the use of digital, mobile and wireless technologies to support the achievement of health objectives. Digital health includes the general use of ICT for health, and advanced technologies for managing vast amounts of data and information such as AI and for use in fields such as genomics (WHO, 2021).

Genomics refers to the study of an individuals’ complete set of genetic information such as in human DNA and other organisms. In recognition of the enormous potential benefits of genomics (and related precision medicine) in health care, including disease prevention, treatment, research the Australian government is establishing Genomics Australia on 1 July 2025.

This highlights some key, yet diverse, capability areas that may be required for professional and non-professional digital health roles.

The many existing and evolving frameworks and competencies that guide a digitally capable health professional to be safely engaged in digital health care each feature different levels of competence (see Section 4) knowledge, skills and attitudes (Rettinger et al., 2024).

There are also many frameworks for specific professions or settings, and a standardised approach to items and definitions for digital health competence is challenging. A scoping review by Nazeha et al. (2020) identified over 30 digital health competency frameworks, concluding that digital health training should focus on competencies relevant to each work group, role, seniority and setting, and they should also be regularly updated.

Table 1 provides an overview of the various professions engaged in digital health and their associated organisations. It is not exhaustive of all professions, organisations and frameworks.

Digital health is not the domain of one profession; rather, it is multidisciplinary and interprofessional. It involves a wide range of professionals, including healthcare providers, IT specialists, data scientists, engineers, policymakers and digital health strategists, all collaborating to design, implement and manage health technologies that enhance patient care, optimise workflows and improve healthcare outcomes across the world. Globally, the number of professions engaged in digital health is vast highlighting the need for standards and competencies to ensure the safe implementation of health informatics.

Equity and inclusion are also central to digital health practice. As digital health systems evolve, it is essential that nurses and midwives are culturally responsive. This includes recognising and addressing the specific health needs and data sovereignty of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples (Ryder et al., 2022), whose knowledge systems, languages, and perspectives must be valued and integrated within digital health initiatives.

Education for health professionals is critical, and every nurse and midwife must be a digital nurse or digital midwife. Beyond preregistration education, certification programs such as that provided by Certified Health Informatician Australasia (CHIA) serve as formal recognition of specialised health informatics knowledge and skills (Vallely et al., 2024). Ongoing professional development is discussed in more detail in Section 4.

Table 1: A sample of global digital health competency roles, organisations, frameworks and competencies

| Health data scientist | |

|---|---|

| Canadian Institute of Health Information (CIHI) | Health Data and Information Governance and Capability Framework: Toolkit

Classified at levels: core, foundational, supplemental, enabling Areas: strategy and governance, policies and processes, assets and standards, people and knowledge |

| Health informatics | |

| American Medical Informatics Association (AMIA) | AMIA 2017 core competencies for applied health informatics education at the master’s degree level

Key aspects of competencies (knowledge, skills, and attitudes) |

| Australasian Institute of Digital Health (AIDH)

|

Australian Health Informatics Competency Framework (2nd ed., February 2022) [PDF]

The CHIA exam covers six areas: (AIDH, 2022) |

| Digital Health Canada | Health Informatics Professional Competencies (2022) [PDF]

Domains: information sciences, health sciences, management sciences |

| Gulf Cooperation Council Health Informatics Workforce Working Group | Toward the development of the GCC Health Informatics Career Paths and Matrix (Almalki et al., 2021) |

| Faculty of Informatics United Kingdom | Competency framework for clinical informatics

Domains: (Davies et al., 2021, p. 8) |

| Health information and communications technologists | |

| American Health Information Management Association (AHIMA) | AHIMA is the national professional association for health information professionals in the US |

| Canadian Health Information Management Association (CHIMA) | CHIMA is the national professional association for the health information profession in Canada |

| Health information managers | |

| Health Information Management Association of Australia (HIMAA) | Digital competency domains: • general professional skills • language of health care • healthcare terminologies and classifications • research methods • health services organisation and delivery • health information law and ethics • e-Health • health information services organisation and management |

| Australian Library & Information Association (ALIA) and Health Libraries Australia (HLA) | ALIA health library guidelines and competencies |

| Medical Library Association (MLA) | Health sciences librarians are master’s degree information professionals, librarians or informaticists with specialised knowledge in finding, accessing and sharing quality health information resources with clinicians, nurses, pharmacists and other members of the health care team |

| Health service managers and leaders | |

| Australasian College of Health Service Management (ACHSM) | Digital competencies:

• manages business and clinical requirements using digital tools (ACHSM, 2022) |

| Health Service Executive and Digital Health and Social Care Northern Ireland (HSEDHSC) | All-Ireland digital capability framework for health and social care

Digital competency domains: (HSEDHSC, 2022) |

| Health professions | |

| Nursing and Midwifery

Australian Digital Health Agency |

National Nursing and Midwifery Digital Health Capability Framework [PDF]

Digital competency domains: (Australian Digital Health Agency, 2020) |

| Allied health

Victorian Department of Health |

Digital Health Capability Framework for Allied Health professionals

Digital competency domains: |

| Primary health care | Digital competency domains: • optimal use of EMRs • basic computer and internet use • knowledge about digital administrative and organisational competencies • artificial intelligence • smartphone applications for monitoring care(Jimenez et al., 2020) |

| Australian Medical Council (AMC) | Digital Health in Medicine Capability Framework [PDF] |

2. Applications of digital health systems and how they are implemented

2.1 Understanding digital health systems in a healthcare setting

Digital health systems applications refer to the use of technology to improve and streamline various aspects of healthcare delivery. These applications aim to enhance patient care, increase efficiency and reduce costs through the integration of digital tools Below are some common examples of digital health systems applications used in health care (increasingly by nurses and midwives) which enhance access to health care across geographical, social and cultural barriers (Almond & Mather, 2023) and in rural and remote areas, reducing travel times and the need for in-person visits.

Telehealth

Telehealth refers to the use of electronic communications technology to provide care and patient education and facilitate self-care at a distance, including through patient portals, e-consults, video visits and remote patient monitoring. Modification of the term can be used to distinguish the health professional utilising telehealth in patient care, e.g., telemidwifery, telemedicine, telenursing.

Website

Read more about Telehealth competencies on the AAMC website.

Virtual care

According to Kleib et al. (2024), virtual care:

facilitates the delivery of health care services via remote communication between patients and health care providers, either synchronously or asynchronously, through information communication technology. (Kleib et al., 2024, p. 1)

Virtual care examples include the Victorian Virtual Emergency Department at Northern Health in Epping, Melbourne, and the virtual care clinics provided by healthdirect (an Australia-wide free health advice service).

Activity

Search for virtual care clinics in your geographical area.

- Identify the types of virtual care services they provide.

- What technology is required to access this care?

Electronic medical records

Electronic medical records (EMRs) are digital versions of paper-based charts used in hospital and community settings which contain patients’ medical history, diagnoses, medications, allergies, diagnostics, radiology imaging and treatment plans (Almond & Mather, 2023). EMRs are also used to store and facilitate the sharing of patient information across a multidisciplinary healthcare team. EMR implementation has improved patient outcomes, enhanced clinical decision-making and reduced medical errors (Adeniyi et al., 2024).

Mobile health applications

Mobile health applications (apps) include health-related tools that are installed on smartphones or tablets. They often focus on wellness, chronic disease management or health tracking. Examples include vital signs tracking, reminders for medication administration and the delivery of health education and wellness information (Maab et al., 2022).

Website

See six examples of great healthcare apps at DBS Interactive.

Wearable devices

A wearable health device is any kind of electronic device that is worn on a person’s body. Devices like smartwatches or fitness trackers collect real-time data on the wearer’s health status and might handle continuous monitoring of vital signs such as blood pressure or heart rate and tracking sleep patterns or physical activity (Teixeira et al., 2021).

Health information exchange

A health information exchange (HIA) allows nurses, midwives and other health professionals to share vital health information electronically through a secure and private application, improving the speed and cost of care (Almond & Mather, 2023).

Artificial intelligence and machine learning

Artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) are increasingly used in healthcare applications to analyse large datasets and identify patterns, risks and predictive outcomes for health conditions (Alowais et al., 2023). Examples include medical imaging analysis, predictive analytics for early disease detection, personalised treatment plans and recommendations based on data analytics.

2.2 Implementation strategies for digital health

Digital health transformation requires planning and preparation, and change will affect the workforce, workflow and resources (Lloyd et al., 2023). However, translation of in-person clinical care to digital care is often ill-prepared to optimise the benefits (DeLaRosby et al., 2024). Planning, implementation and understanding roles and competencies for applications is critical to success and can have positive and negative impacts on clinician wellbeing (Livesay et al., 2023; Wosny et al., 2023).

Implementing digital health solutions effectively requires comprehensive strategies to ensure successful integration into healthcare settings. These strategies should address technology adoption, infrastructure, training, and ongoing evaluation. One example of a framework used to implement healthcare interventions such as digital health is the COMPASS model (Mather & Almond, 2022). Table 2 sets out what the letters of COMPASS stand for.

Table 2: Context optimisation model for person-centred analysis and systematic solutions

| C | Context | Understanding the environment or setting in which digital health will be implemented. This includes knowing the culture of the environment, resources and external factors such as politics and finances prior to implementation. |

| O | Organisational readiness | An assessment of whether your workplace or organisation is ready to adopt the change. This may include ensuring your workplace has champions who are experienced and knowledgeable prior to implementation. |

| M | Measurement | Identifying ways to measure implementation outcome success. This may include patient outcomes, process measures and patient and staff satisfaction. |

| P | Process | Understanding the step-by-step actions, methods and strategies for implementing the new digital health application. |

| A | Adaptation | Ensuring flexibility in the intervention is available to allow for adjustments or modifications based on real-time feedback. |

| S | Sustainability | Ensuring that the intervention is maintained after the initial phase begins and putting ongoing strategies in place for long-term support. |

| S | Stakeholders | Engaging staff, patients, managers and external partners in the implementation phase is important to ensure buy-in and acceptance of change. |

The COMPASS framework and implementation model offers a structured and adaptable approach to implementing health interventions, particularly in digital health contexts. By addressing key components such as context, readiness, measurement, process, adaptation, sustainability and stakeholder engagement, it ensures that digital health initiatives are effectively integrated into healthcare systems and are more likely to achieve long-term success and improved outcomes.

Activity

Check Mather and Almond’s (2022) article on COMPASS to review implementation strategies for digital health in greater detail:

3. Challenges and strategies for a digital health workforce

3.1 Challenges for digital health systems implementation

The impact of digitalisation on the nursing and midwifery workforce has been profound. As health and care continue to rapidly transform through technological advancements and the growth of data science, these changes will continue to have lasting and widespread implications. Digital literacy continues to be a challenge, with many health professionals unprepared to fully harness the potential benefits of digital health. A large proportion of the current workforce has not been trained in digital health care and has had limited opportunities for upskilling, with most attempts being reactive ‘on the job’ training (Woods et al., 2023). Implementing digital health also requires a focus on diversity and inclusion, especially for First Nations people in rural settings, to ensure equitable access for all (Carpenter et al., 2020). Barriers such as digital literacy, cultural appropriateness and access to services are just some of the challenges faced by First Nations people.

According to Wynn et al. (2023), nurses’ resistance to the adoption of digital technology is not a new issue. Resistance to using computers, extensive criticism and concerns about reliability of technology, the degradation of skills or less time spent with face-to-face patient care were some of the challenges experienced by nurses during the implementation of digital health systems (Wynn et al., 2023).

Case Study

Isaac is the nurse unit manager (NUM) of a busy surgical ward in a tertiary referral hospital. The hospital recently informed all NUMs that EMR systems implementation would occur in all wards at the start of the following month, and the NUMs were responsible to ensure this was successful. Isaac and other NUMs therefore have one month to prepare and train all staff in the EMRs, including many senior staff with no previous exposure to EMRs. Four staff members have already refused to attend training outside their work hours despite being aware of the implementation, stating they did not have time for training nor that it was necessary. They think it is a waste of time.

Inampudi et al. (2024) found that resistance to change negatively affected healthcare workers’ intentions to adopt digital care solutions. Other challenges for facilities include:

- costs to implement digital health infrastructure

- added costs to network coverage

- employing experts in digital health

- data privacy and confidentiality

- IT infrastructure

- training to ensure digital literacy for nurses and midwives.

Activity

- Identify three challenges Isaac has as a NUM to successfully implement technology like EMR into a busy surgical ward.

- Identify the challenges health services may have when implementing technology like EMR into wards and units.

3.2 Strategies to support a digitally capable workforce

The digital workplace has become a powerful solution to many of the challenges faced by traditional work environments, such as poor collaboration, low engagement and inefficient processes. This shift has been accelerated by significant changes in the way we work, alongside the rise of a digitally capable workforce. Advances in technology have made it easier for healthcare staff to access patient data from virtually anywhere, removing the constraints of relying on physical records that are limited to a single location. However, to fully harness the potential of remote and hybrid access to patient data, nurses and midwives need strategies to efficiently leverage a digitally capable workforce. These strategies should empower healthcare professionals to work more flexibly, optimising the technology available to them. This approach can ultimately improve productivity, communication, engagement and, most importantly, patient outcomes. Digital workplace strategies provide a way for organisations to stay ahead of evolving work trends while enhancing operational processes and the overall employee experience.

According to Woods et al. (2023), strategy development has become a priority in Australia through lessons learned from challenges that have been faced locally and internationally. The Australian National Nursing and Midwifery Digital Health Framework is an important example of current Australian workforce strategies to implement digital health into patient care. The framework encompasses key domains and a structured approach that outlines the skills and knowledge needed to foster and support a digitally capable health workforce.

Revisit Table 1 to review the Australian strategies to build a digitally capable workforce.

4. Maintaining support and development for a digital health workforce

4.1 Digital competencies for nurses and midwives

Digital competencies are recognised elements of health professional education. Information literacy and digital competence are essential to ensure nurses and midwives are open to technology and have the necessary skills to effectively manage the increase of digital information critical to their roles. The healthcare workforce must understand how digital technology works and what it can and cannot do to inform safe and effective nursing and midwifery practice.

The Australian Digital Health Agency is tasked with implementing the strategy to support a workforce confidently using digital health technologies to deliver health and care. As the nursing and midwifery professions collectively represent Australia’s largest health workforce component, it is imperative that these professions define the core digital competencies that nurses and midwives will need to take direct responsibility for the collection, data entry and use of clinical information.

Digital capability domains

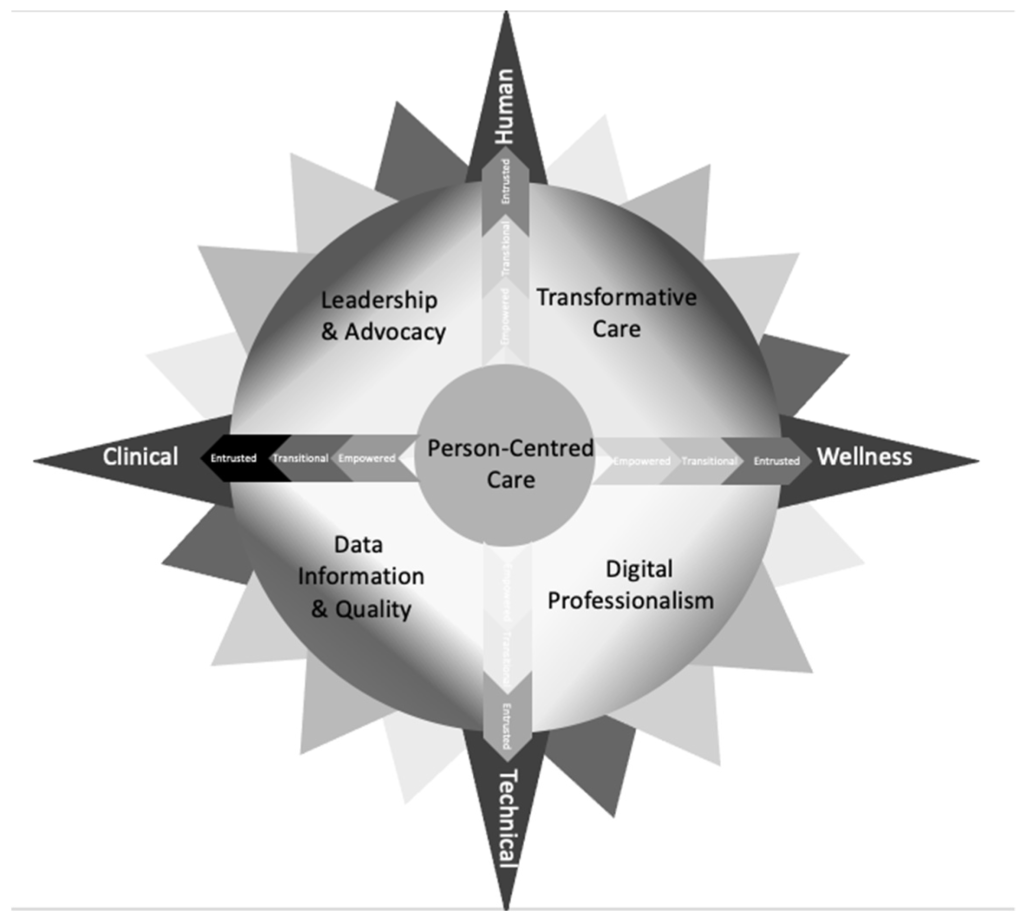

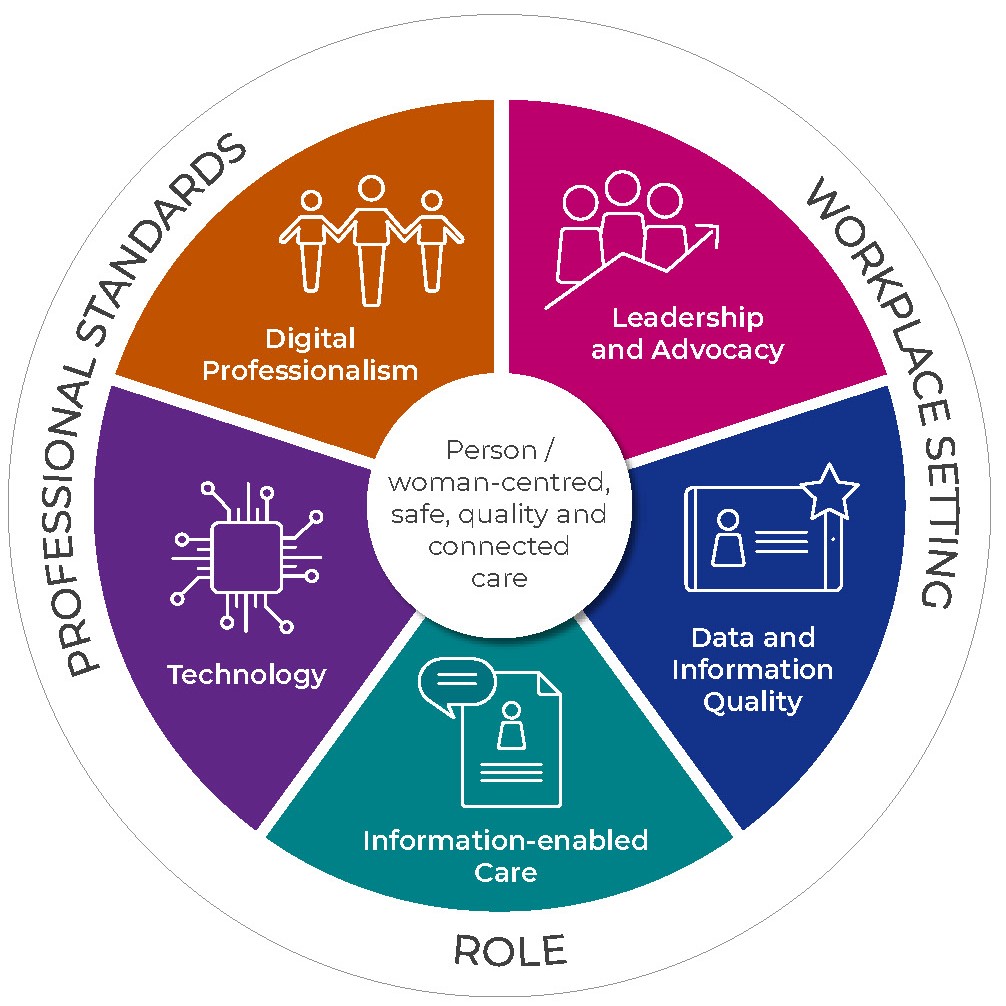

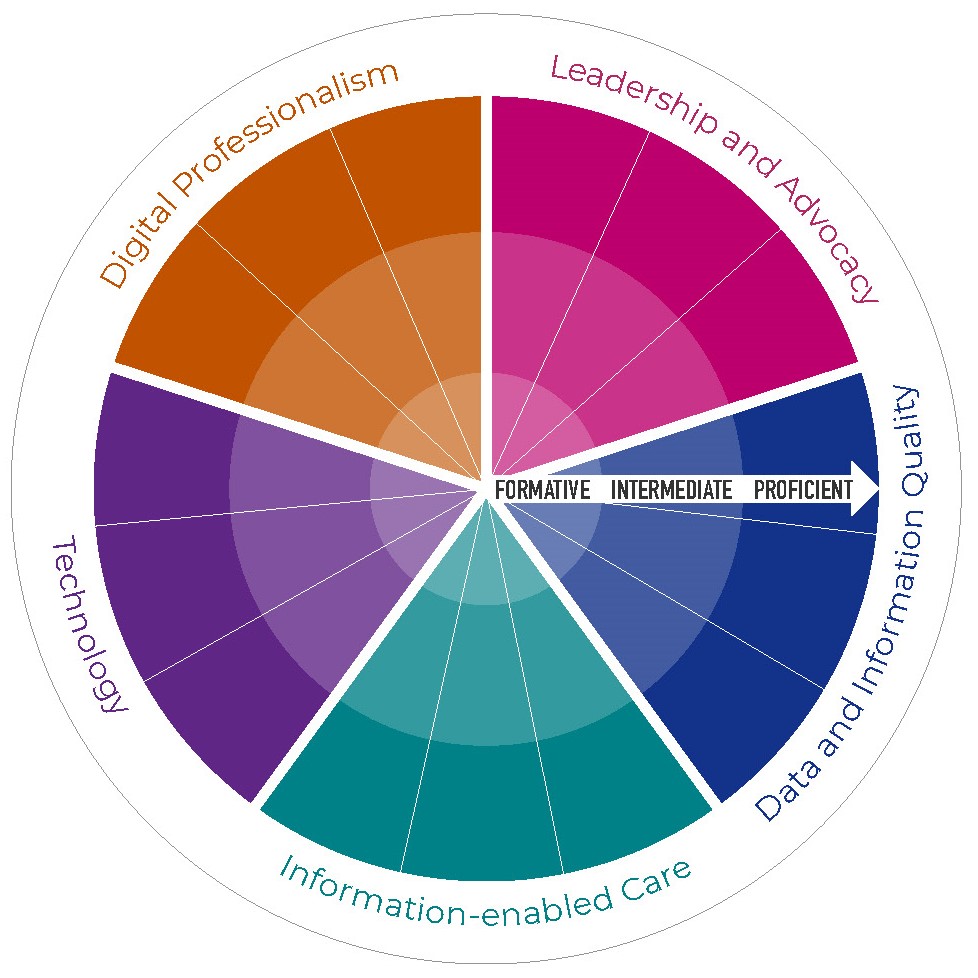

The Australian Digital Health Agency has identified the required digital capabilities based on the roles of nurses and midwives to support their education and training. As shown in Figure 3, the major domains are:

- Digital professionalism

- Leadership and advocacy

- Data and information quality

- Information-enabled Care

- Technology.

These domains in turn have capacity levels that anticipate growth of knowledge, skills and abilities that are formative, intermediate and proficient (see Figure 4). The framework extends the description of competence beyond the technical skills implied to encompass the capability to address wider aspects of professionalism and continuous development, rather than assessing competence of a skill at a particular moment in time. Frameworks such as the one developed by the Australian Digital Health Agency provide a way for individuals and organisations to promote and encourage positive attitudes in relation to the increasing introduction and adoption of technology and innovation. Nurses and midwives can use such frameworks to assess their own capability across digital health domains. Other healthcare professionals and organisations can also use the framework to understand the digital health capabilities of nurses and midwives.

4.2 Ongoing professional development

To address the gap in digital health literacy, various methods of education and training should be used to gain, maintain and improve the digital health literacy of nurses and midwives. However, not all staff need to be digital experts and having a small number of digital experts in a certain area would ensure staff have access to ‘in-the-moment’ training from experts. The minimum standards of digital literacy for health professionals have been outlined in the case studies below as a basis to support beginner digital competency.

Digital capability competencies

The framework intends to promote and encourage positive attitudes in relation to the increasing introduction and adoption of technology and innovation for novices. Competencies at the formative stage include using email for communication, video conferencing, EMRs, virtual health care and cyber security (Morris et al., 2023). Training on digital professionalism such as using technology at the bedside, training on the use and value of data in digital systems and providing lifelong training when staff transition into leadership roles are also important considerations in developing nurses’ and midwives’ intermediate digital capability. The proficient level reflects nurses and midwives in leadership roles who are championing digital health in practice and in the broader nursing and midwifery professions.

Capability level case studies

The following case studies demonstrate examples of suggested capability levels based on how nurses and midwives can leverage digital capabilities to enhance their practice, contribute to their teams and drive positive changes in health care. The capability framework supports nurses and midwives to effectively engage with technology to improve patient care, support their colleagues and drive innovation in health care specific to the needs of the nursing and midwifery professions but also to health care more broadly.

Level 1: Awareness

Familiarisation with digital tools

Scenario: Akio, a newly graduated midwife, is introduced to a digital tool for tracking prenatal appointments. During her orientation, she learns the basics of logging in and navigating the system. While she primarily uses paper-based records, she attends a workshop where she observes how experienced colleagues use the digital tool to streamline appointment scheduling.

Outcome: By the end of her orientation, Akio feels more confident about using the tool and recognises its potential to improve communication with patients. She starts integrating it into her workflow during patient visits.

Level 2: Foundational

Implementing digital documentation

Scenario: Carlos a registered nurse, has been working on a surgical ward and is transitioning from paper-based documentation to an electronic health record (EHR) system. He attends training sessions to learn how to document patient assessments digitally.

Outcome: Carlos quickly adapts to the EHR, using it to record vital signs and medication administration. He also starts helping colleagues who struggle with the transition, fostering a collaborative learning environment that improves overall team efficiency.

Level 3: Intermediate

Using data for patient safety

Scenario: Remy, a nurse in a busy emergency department (ED), analyses data from the EHR to identify patterns in patient wait times. She discovers that patients presenting with chest pain often wait longer than average for triage.

Outcome: Remy presents her findings at a staff meeting, leading to the implementation of a new triage protocol that prioritises chest pain presentations. This change significantly reduces wait times and improves patient outcomes in the ED.

Level 4: Advanced

Leading a telehealth initiative

Scenario: Davos, a nurse educator, is tasked with developing a telehealth program for managing chronic diseases. He collaborates with IT and the multidisciplinary team of healthcare professionals to design an interactive platform for patient education and monitoring.

Outcome: The telehealth program is launched successfully, allowing patients to receive real-time feedback on their health data. Davos trains staff on using the platform effectively, resulting in increased patient engagement and better management of chronic conditions.

Level 5: Expert

Influencing national digital health policy

Scenario: Clinical Professor Finn (RN, RM, CHIA), an expert in digital health, is invited to a national committee to discuss the future of healthcare technology. Finn presents evidence-based recommendations on integrating AI into nursing and midwifery workflows to enhance person-centred assessments and clinical decision-making.

Outcome: The national committee insights lead to the formulation of guidelines that promote AI use across healthcare settings, ultimately improving care quality and efficiency. Finn also mentors other nurse and midwife leaders, ensuring a sustainable approach to digital health innovations.

Generative artificial intelligence

Higher education providers and health services both need to play a role in ensuring the digital capability of the health workforce. In the past, university preregistration education programs providing basic digital health education to students have relied on health services to teach digital technologies on clinical placement (e.g. EMRs and mobile computers/digital workstations) (Raghunathan et al., 2023).

However, with the emergence of generative artificial intelligence (GAI) and other technologies, universities have needed to quickly develop strategies to improve delivery of technology into curricula to prepare students for the evolving digital health care landscape.

AI, and GAI, are poised to revolutionise health care, promising to improve health outcomes and enhance clinical decisions (Reddy, 2024). GAI is a subset of AI that generates images, text and other media based on human prompts. AI and GAI are discussed in more detail in other chapters.

Strategies to support a digitally capable workplace include integrating minimum standards of digital literacy into undergraduate nursing and midwifery programs, and universities partnering with healthcare organisations to provide digital literacy micro-credentialling to improve the digital literacy of the healthcare workforce appropriate to their role and skill levels.

The following concept box provides some examples of how nursing and midwifery educators can incorporate GAI to prepare preregistration students for digital health in practice.

GAI in nursing and midwifery preregistration education programs

GAI could be used for:

- the enhancement of simulation-based learning by generating realistic and complex patient care scenarios based on the level of the learner

- personalised education through analysing learning patterns to tailor educational content to the needs of the student (Li et al., 2024)

- creating education modules and materials that can be scaled and distributed across different institutions, health services and other organisations

- helping educators by automating routine tasks like preparing and marking educational materials.

5. Future directions

5.1 Future workforce trends and challenges in nursing and midwifery due to evolving roles and models of care

Despite significant advances, there has been concern that the professions of nursing and midwifery have not kept pace with digital advancement in health care (Morris et al, 2023). To respond to these challenges and embrace the benefits of a rapid transformation, the professions need to be responsive and adaptive and inclusive. Nurses and midwives currently use digital health care by using telehealth to triage, assess, diagnose and monitor patients remotely, and by using smartphone applications to support self-monitoring of patients. Many applications are also used in education for nurses and midwives. The integration of GAI and robotics in health care presents a unique opportunity for nurses and midwives to take on leadership roles in technology implementation. By leveraging advancements, they can enhance patient care, streamline processes and improve outcomes.

As frontline caregivers, nurses and midwives are well positioned to identify areas where technology can make a meaningful impact. Their insights can drive the development of tools that not only support clinical tasks but also enhance patient engagement, health literacy, cultural responsiveness and education. Furthermore, embracing these technologies allows them to focus on the human aspects of care, such as empathy and communication, while technology supports more routine tasks.

Healthcare professions, including nursing and midwifery, rely on multidisciplinary teamwork, and the potential for GAI to streamline tasks and enhance coordination offers an exciting opportunity for greater efficiency in teams. In addition, GAI has the capacity to enhance the collective knowledge of healthcare teams. Imagining GAI as an integral component that provides critical insights for shared decision-making suggests a future where technology effectively complements human expertise. Furthermore, nurses emphasise the importance of effective communication among healthcare professionals. GAI’s role in facilitating information sharing aligns with their dedication to improving inclusive, safe and effective patient outcomes, illustrating a forward-thinking approach that integrates collaboration and technology for the advancement of patient care.

5.2 Maintaining the person at the centre of care in a digital environment

Digital technologies such as GAI provide an opportunity to enhance patient care and streamline healthcare processes. However, it is important to consider the unique role nurses and midwives have in caring for people. Compassionate care, advocacy and human connection are the cornerstone of the roles of nurses and midwives. Even while embracing innovation, it is the nurse’s or midwife’s unique ability to forge authentic bonds that distinguishes their practice (Rony et al., 2024).

It is crucial for healthcare education and ongoing professional development to adapt, equipping nursing and midwifery professionals with the skills to navigate and lead in this evolving landscape. This proactive approach ensures that they remain integral to the healthcare team and can advocate effectively for their patients in a technology-driven environment.

Activity

- How do you perceive the collaboration between GAI technologies and human nurses and midwives? What roles and responsibilities do you envision for GAI in enhancing person-centred or woman-centred care, and how do you see these roles evolving?

- What ethical considerations do you believe should be considered when integrating GAI into nursing or midwifery care? How can these considerations be addressed to ensure patient safety, privacy and overall wellbeing?

6. Conclusion

Digital health transformation is disrupting and challenging traditional healthcare roles and boundaries. While largely welcomed, it creates challenges in establishing what might be considered core competencies across the many current and emerging digital health roles and digital health care settings.

This chapter has discussed the evolving digital health workforce capabilities and examined the key role of nurses and midwives in leading change and the successful implementation of digital health systems.

Digital health systems and applications aim to improve access, efficiency, quality and sustainability of healthcare delivery. The future success of digital health systems is reliant not just on readily accessible technology but also on ensuring we have a digitally capable workforce.

Building and sustaining workforce capability through education and training is therefore critical. Factors for success include employer support, overcoming clinician resistance, and clear digital health career pathways and professional development.

7. Further reading

Babu, S. R., Kumar, N. V., Divya, A. S., & Thanuja, B. (2024). AI-driven healthcare: Predictive analytics for disease diagnosis and treatment. International Journal for Modern Trends in Science and Technology,10(6), 5–9. https://doi.org/10.46501/IJMTST1006002

Greenhalgh, T., Hinder, S., Stramer, K., Bratan, T., & Russell, J. (2010). Adoption, non-adoption and abandonment of an internet-accessible personal health organiser: Case study of HealthSpace. British Medical Journal, 201, c5814.

Topol, E. (2019). Preparing the healthcare workforce to deliver the digital future. The Topol Review – An independent report on behalf of the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. National Health Service. https://topol.hee.nhs.uk/the-topol-review/

8. References

Adeniyi, A., Arowoogun, J., Chidi, R., Okolo, C., & Babawarun, O. (2024). The impact of electronic health records on patient care and outcomes: A comprehensive review. World Journal of Advanced Research and Reviews. 21. 1446–1455. https://doi.org/10.30574/wjarr.2024.21.2.0592

Almalki, M. Jamal, A., Elhassan, O., Zakaria, N., Alhefzi, M. (2021). Toward the development of the GCC Health Informatics Career Paths and Matrix. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine, 205, Supplement, 105987.

Almond, H., & Mather, C. (2023). Digital health: A transformative approach. Elsevier.

Alowais, S. A., Alghamdi, S. S., Alsuhebany, N., Alqahtani, T., Alshaya, A. I., Almohareb, S. N., Aldairem, A., Alrashed, M., Bin Saleh, K., Badreldin, H. A., Al Yami, M. S., Al Harbi, S., & Albekairy, A. M. (2023). Revolutionizing healthcare: The role of artificial intelligence in clinical practice. BMC Medical Education, 23(1), 689. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-023-04698-z

Australasian College of Health Service Management. (2022). Master Health Service Management Competency Framework. https://www.achsm.org.au/education/competency-framework

Australian Digital Health Agency. (2020). National Nursing and Midwifery Digital Health Capability Framework. Australian Government. https://www.digitalhealth.gov.au/sites/default/files/2020-11/National_Nursing_and_Midwifery_Digital_Health_Capability_Framework_publication.pdf

Australian Institute of Digital Health. (2022). Australian Health Informatics Competency Framework (2nd ed.).

Australian Institute of Digital Health. (2023). Australian digital health workforce insights. https://digitalhealth.org.au/wp-content/uploads/2024/02/AIDH_VMWare-Workforce-Insights_2023_V3.pdf

Butler-Henderson, K., Gray, K., & Arabi, S. (2024). Roles and responsibilities of the global specialist digital health workforce: Analysis of global census data. JMIR Medical Education, 10(1), e54137. https://mededu.jmir.org/2024/1/e54137/

Carpenter, J., Guerin, A., Kaczmarek, M., Lawson, G., Lawson, K., Nathan, L. P., & Turin, M. (2016). Digital access for language and culture in First Nations communities (Doctoral dissertation, Knowledge Synthesis Report for Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada). https://shs.hal.science/halshs-03083456v1

Davies, A., Mueller, J., Hassey, A., & Moulton, G. (2021). Development of a core competency framework for clinical informatics. BMJ Health & Care Informatics, 28(1).

Health Service Executive and Digital Health and Social Care Northern Ireland. (2022). Digital Capability Framework for Health and Social Care. https://online.hscni.net/digital-hcni/digital-capacity-capability/

Inampudi, S., Rajkumar, E., Gopi, A., Vany Mol, K. S., & Sruthi, K. S. (2024). Barriers to implementation of digital transformation in the Indian health sector: A systematic review. Humanities & Social Sciences Communications, 11(1). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-03081-7

Jimenez, G., Spinazze, P., Matchar, D., Huat, G. K. C., van der Kleij, R. M., Chavannes, N. H., & Car, J. (2020). Digital health competencies for primary healthcare professionals: A scoping review. International Journal of Medical Informatics, 143, 104260. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2020.104260

Kleib, M., Arnaert, A., Nagle, L. M., Darko, E. M., Idrees, S., da Costa, D., & Ali, S. (2024). Resources to Support Canadian Nurses to Deliver Virtual Care: Environmental Scan. JMIR Medical Education, 10(1), e53254. https://doi.org/10.2196/53254

Lawrence, K., & Levine, D. L. (2024). The digital determinants of health: A guide for competency development in digital care delivery for health professions trainees. JMIR Medical Education, 10, e54173.

Li, H., Xu, T., Zhang, C., Chen, E., Lian, J., Fan, X., Li, H., Tang, J., & Wen, Q. (2024). Bringing generative AI to adaptive learning in education. arXiv, 2402.14601. https://arxiv.org/pdf/2402.14601

Livesay, K., Petersen, S., Walter, R., Zhao, L., Butler-Henderson, K., & Abdolkhani, R. (2023). Sociotechnical challenges of digital health in nursing practice during the COVID-19 pandemic: national study. JMIR nursing, 6, e46819. https://doi.org/10.2196/46819

Lloyd, S., Olley, R., & Milligan, E. (2023). Leading in health and social care leadership concepts and practices to strengthen health and social care services. Open Educational Resources Collective. https://oercollective.caul.edu.au/leading-in-health-and-social-care/

Maaß, L., Freye, M., Pan, C.-C., Dassow, H.-H., Niess, J., & Jahnel, T. (2022). The definitions of health apps and medical apps from the perspective of public health and law: Qualitative analysis of an interdisciplinary literature overview. JMIR mHealth and uHealth, 10(10), e37980. https://doi.org/10.2196/37980

Mather, C., & Almond, H. (2022). Using COMPASS (context optimisation model for person-centred analysis and systematic solutions) theory to augment implementation of digital health solutions. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(12), 7111. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19127111

Morris, M. E., Brusco, N. K., Jones, J. , Taylor, N. F., East, C. E., Semciw, A. I., Edvardsson, K., Thwaites, C., Bourke, S. L., Raza Khan, U. et al. (2023). The widening gap between the digital capability of the care workforce and technology-enabled healthcare delivery: A nursing and allied health analysis. Healthcare, 11, 994. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11070994

Nazeha, N., Pavagadhi, D., Kyaw, B. M., Car, J., Jimenez, G., & Tudor Car, L. (2020). A digitally competent health workforce: Scoping review of educational frameworks. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 22(11), e22706.

Raghunathan, K., McKenna, L., & Peddle, M. (2023). Baseline evaluation of nursing students’ informatics competency for digital health practice: A descriptive exploratory study. Digital Health. May 30, 9:20552076231179051. doi:10.1177/20552076231179051.

Reddy, R. (2024). Generative AI for enhanced engagement in digital wellness programs: A predictive approach to health outcomes. SSRN. https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.5022990

Rettinger, L., Putz, P., Aichinger, L., Javorszky, S. M., Widhalm, K., Ertelt-Bach, V., … & Kuhn, S. (2024). Telehealth education in allied health care and nursing: Web-based cross-sectional survey of students’ perceived knowledge, skills, attitudes, and experience. JMIR Medical Education, 10(1), e51112.

Rony, M. K. K., Kayesh, I., Bala, S. D., Akter, F., & Parvin, M. R. (2024). Artificial intelligence in future nursing care: Exploring perspectives of nursing professionals – a descriptive qualitative study. Heliyon, 10(4), e25718. https://doi:10.1016/j

Ryan, A., Gee, B. L., Fenton, S. H., & Makeham, M. (2021). The impact on safety and quality of care of the specialist digital health workforce. In K. Butler-Henderson, K. Day, & K. Gray (Eds.), The health information workforce: Health Informatics. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-81850-0_13

Ryder, C., Wilson, R., D’Angelo, S. et al. Indigenous Data Sovereignty and Governance: The Australian Traumatic Brain Injury National Data Project. Nat Med 28, 888–889 (2022). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-022-01774-7

Teixeira, E., Fonseca, H., Diniz-Sousa, F., Veras, L., Boppre, G., Oliveira, J., Pinto, D., Alves, A. J., Barbosa, A., Mendes, R., & Marques-Aleixo, I. (2021). Wearable devices for physical activity and healthcare monitoring in elderly people: A critical review. Geriatrics, 6(2), 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/geriatrics6020038

Stoumpos, A. I., Kitsios, F., & Talias, M. A. (2023). Digital transformation in healthcare: Technology acceptance and its applications. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 20(4), 3407. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph20043407

Valenta, A., Berner, E. S., Boren, S. A., Deckard, G. J., Eldredge, C., Fridsma, D. B., Gadd, C., Gong, Y., Johnson, T., Jones, J., LaVerne Manos, E., Phillips, K. T., Roderer, N. K., Rosendale, D., Turner, A. M., Tusch, G., Williamson, J. J., & Johnson, S. B. (2018). AMIA Board White Paper: AMIA 2017 core competencies for applied health informatics education at the master’s degree level. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 25(12), December, 1657–1668. https://doi.org/10.1093/jamia/ocy132

Vallely, D., McNeile McCormick, D., & Bichel-Findlay, J. (2024). An exploration of the Certified Health Informatician Australasia (CHIA) participants over 10 years. In Health. Innovation. Community: It starts with us (pp. 114–19). IOS Press.

Woods, L., Janssen, A., Robertson, S., Morgan, C., Butler-Henderson, K., Burton-Jones, A., & Sullivan, C. (2023). The typing is on the wall: Australia’s healthcare future needs a digitally capable workforce. Australian Health Review, 47(5), 553–558. https://doi.org/10.1071/AH23142

World Health Organization. (2021). Global strategy on digital health 2020–2025. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/344249

Wosny, M., Strasser, L. M., & Hastings, J. (2023). Experience of health care professionals using digital tools in the hospital: qualitative systematic review. JMIR human factors, 10(1), e50357. https://doi.org/10.2196/50357

Wynn, M., Garwood-Cross, L., Vasilica, C., Griffiths, M., Heaslip, V., & Phillips, N. (2023). Digitizing nursing: A theoretical and holistic exploration to understand the adoption and use of digital technologies by nurses. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 79(10), 3737–3747. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.15810

The process of converting analogue information into a digital format, enabling the content to be programmed, addressed, traced and communicated.

Fahndrich, J. (2023). A literature review on the impact of digitalisation on management control. Journal of Management Control, 34(1), 9–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00187-022-00349-4

The application of information and communication technologies in the fields of health care and medicine.

Jandoo, T. (2020). WHO guidance for digital health: What it means for researchers. Digital Health, 6, 2055207619898984–2055207619898984. https://doi.org/10.1177/2055207619898984.

An interdisciplinary field that focuses on the effective use of biomedical data, information and knowledge for scientific research, problem-solving and decision making with the goal to enhance human health.

Jen, M. Y., Mechanic, O. J., & Teoli, D. (2023). Informatics. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing.

Founded in 1948, WHO is the United Nations agency that connects nations, partners and people to promote health, keep the world safe and serve the vulnerable.

Refers to the ability to effectively and critically navigate and create information using a range of digital skills.

Tinmaz, H., Lee, Y.-T., Fanea-Ivanovici, M., & Baber, H. (2022). A systematic review on digital literacy. Smart Learning Environments, 9(1), 21. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40561-022-00204-y.

The ethical obligation to protect private and sensitive information from unauthorised disclosure.

The integration of digital technology into all areas of a business, fundamentally changing how it operates and delivers value to customers.

Andriole, S. J. (2020). The hard truth about soft digital transformation. IT Professional, 22(5), 13–16. DOI: 10.1109/MITP.2020.2972169.