Power and how it manifests

Mary-Claire Balnaves; Annabel Ahuriri-Driscoll; Jennie Briese; Deb Duthie; Lana Elliott; Shelley Hopkins; Kate Murray; and Lydia Roberts

Introduction

When discussing Cultural Safety, ‘cultural competency’ or similar ‘cultural…’ terms are often (and incorrectly) used interchangeably. Whilst there may be some similarities and overlaps, Cultural Safety advocates for an approach that steps beyond understanding ‘the other’. Cultural Safety is grounded in the concept of power and how understanding and challenging power dynamics can lead to more equitable power sharing between individuals, groups and organisations. It requires critical self-reflective practices that go beyond both the consideration of an individual’s personal or professional culture/s (connected to cultural awareness) and practices that legitimise the cultures of others (connected to cultural sensitivity). Encompassing these principles, Cultural Safety goes a step further in encouraging individuals to reflect on and challenge the dimensions of power in their personal, professional, and organisational cultures to promote greater power sharing (Cox et al., 2021).

This chapter will provide a perspective on large, complex, and often compounding systemic issues about power and how it manifests. It is a broad overview of key concepts that provide a starting point to develop, strengthen, and challenge your understanding of Cultural Safety. This will be anchored with reflective questions to build your critical self-reflection skills as well as additional readings to support you in strengthening your understanding of these topics and their alignment with the principles and practices of Cultural Safety.

Power

Why talk about power?

Power remains one of the most contested concepts in social and political theory (Avelino, 2021) and understanding ‘what power is’ is essential for culturally safe practice. Grounded in different theories, including critical and feminist theory, Cultural Safety conceptualises that power can be used to redistribute and redress inequities, which themselves derive from systemic imbalances in power. Cultural Safety hence focuses on how people work together to identify and address power imbalances and power structures that lead to forms of discrimination, including (but not limited to) racism and sexism (Cox & Best, 2022). By centralising considerations of power, we are better able to ‘…challenge and subvert’ power structures and ‘unmask their principles of operation, whose effectiveness is increased by their being hidden from view…’ (Luke, 2005, p. 63). Therefore, understanding power and power differentials at all levels, including personal, professional, organisational, and societal, is essential to Cultural Safety (Curtis et al., 2019).

What is power?

Every person and culture will likely have language, stories, and theories to define and describe power. Providing an all-encompassing definition or description is difficult, as the ‘essence’ of power will look different in each specific context (Avelino, 2021). The Western perspective of power has been drawn from sociologists. An example of this is in the Cambridge Dictionary (2023), which defines power as the ‘ability or authority to make decisions and exercise control over other individuals or groups.’ The way we define power can often ‘…serve to reproduce and reinforce power structures and relations…’ or their ‘continued functioning’ (Luke, 2005). This definition of power is, in itself, an example of power, given:

- There is an identified authority (the dictionary);

- This authority determines the meaning of ideas (in this case, power);

- These ideas can be considered the ‘main’ way to think about the world (becoming a dominant way of knowing, being, and doing).

Reflections from the Authors

We all hold power, but we may only sometimes be aware of the power we hold. We may not have been put in a position to ever examine or question what power we may or may not have. Alternatively, some people may have questioned power and power structures their whole lives. For example, colonised people are often positioned to feel disempowered, however the reality is that power can come from within. This power is often unrecognised due to experiences that can often marginalise or oppress people.

How does power work?

Whilst power can be conceptualised in many ways, it is often categorised. For example, political, social, and economic power are common classifications devised by considering the application of power to various societal structures (Cox et al., 2021).

A misconception of power is that it is a commodity that can be traded or handed over from person to person, group to group, society to society. Rather, power can be understood in terms of class and conditions. For example, in society, there are certain groups of people who influence the distribution of wealth. This form of stratification highlights how those in positions of power might influence profit (or the economy) which has a flow-on effect on all essential human needs like housing, work, and health (Cox et al., 2021).

Reflections from the Authors

Colonial power saw First Nations Peoples denied the ability to own and profit from the means of production due to colonial processes of control over First Nations Peoples and the right to freedoms held by the colonial invaders. This included the right to self-determination in areas such as housing, work and health. The ongoing effects of colonial marginalisation and exclusion of First Nations Peoples from the colony has led to significant power imbalances, where white power and privilege became entrenched in all systems of governance in many nations, including (so-called) Australia. These systems of power have continued to privilege subsequent generations of people who share similar cultural attributes and worldviews, i.e. in the context of Australia, white Australians.

Instead, power is:

- Exercised – with an individual or group being able to act or express themselves. The degree to which power can be exercised is often determined by how social structures are developed and maintained, which may limit or enhance a person’s ability to exercise power;

- Everywhere – ordinary and dispersed at every interface between people and across systems;

- Fluid – how power is exercised can differ across time and context, it is not static;

- Relational – it exists at all levels of interaction. This includes personal levels, such as between individuals or within families. It can also exist in the relationships that groups of people have within society; at professional levels, such as workplaces; and within and across societal structures, such as governments, organisations, and countries.

- Think about a situation where you exercised power.

- What did that look like?

- How did you feel?

- What aspects of who you are enabled you to exercise this power?

- What were the outcomes for you? (e.g. benefits, harms etc.).

- What were the outcomes for others? (e.g. benefits, harms etc.).

- If you were to exercise this power again

- Could you?

- Would you?

- Should you?

- If so, why so, if not, why not?

Who has power?

Foucault (2003) states that ‘everyone has power’. However, current structures often see power exercised in ways that lead to and entrench imbalances between people and groups within society. This dynamic often disenfranchises people and groups who do not follow, understand, or are positioned outside the power structures that reinforce the dominant culture’s rules or norms, impacting their ability to exercise power (Cox et al., 2021). For example, those with a university education benefit from the power that a degree affords a person in society. There are jobs that are unattainable without these qualifications.

Expressing power

Power can be expressed in different ways. Harris et al. (2020) outlines a useful classification for conceptualising expressions of power, it includes:

- Power over: Power built on force, coercion, domination, and control, sometimes motivated through fear. A common example given by Dahl (1957) is when a person (Person A) has power over another person (Person B), and the person with power (Person A) makes another person (Person B) do something they would otherwise not want to do;

- Power with: A shared power that grows out of collaboration and relationships built on respect, mutual support, empowerment and collaborative decision making;

- Power to: Power is built on every person’s potential to make a difference, to create something new, or to achieve goals;

- Power within: This reflects that we all have power. Power derived from an individual or group’s sense of their capacity and self-worth. It allows people to recognise their ‘power to’ and ‘power with’ and believe they can make a difference.

Returning to the dictionary definition of power previously used to ‘exercise control over other individuals or groups’ (Cambridge Dictionary, 2023), this is a clear example of a definition that positions power as something expressed over someone. This expression of power can lead to forms of discrimination, violence, and persecution. Conversely, other areas of literature such as feminist definitions that discuss power distribution start to tap into the other expressions of power: with, to, and within.

Reflecting on power

In previous chapters, we have discussed the vital role of critical self-reflection for Cultural Safety. When the term ‘self’ is used, people tend to position only themselves as individuals in the reflection. Self-reflection on oneself and one’s personal culture is important, but it is not the only component. Critical self-reflection goes beyond the individual and extends to the organisational and institutional cultures, which have their own ‘power dynamics, power imbalances, values, priorities, beliefs and traditions’ that inform and influence how a person engages in the world and, importantly for this context, how they receive health care (Cox et al., 2021). These broader structures underpin how society, and systems within society, function. Critical reflection on these structures is hence essential to culturally safe practice (Cox & Best, 2022; Ramsden, 2002).

Critical Self-Reflection Exercise 1

- How do you define power?

- Where have you previously learned about power? What did you learn? How did you learn it and from whom?

- In your current position or future professional position, why do you think it is important to understand power?

- Consider your current profession and/or organisation you are working in. Using the classifications of power above, how is power expressed in these areas?

Power and sovereignty

What is sovereignty?

Like power, there are many definitions of sovereignty, some of which are contested. Sovereignty is related to power, as it looks at an individual or a group of people’s ability and authority to have power (e.g., govern). Sovereignty can be possessed by an individual or group of people but is often primarily related to occupying a particular position within a state or collective. Moreton-Robinson (2007, p. 33) captures the international definition of sovereignty as ‘the supreme authority in an independent political society’. Often, when considering sovereignty (Moreton-Robinson, 2007), people think it is:

- Absolute: Existing independently, being universal and not relative to anything;

- Monopolistic: Is complete control over something, and something that cannot be shared;

- Irrecoverable: Cannot be regained, recovered, or addressed.

However, sovereignty is not absolute, for example a sovereign state cannot just do whatever it likes, as there are mechanisms such as constitutions and laws that create parameters for sovereignty. Sovereignty therefore is not beyond the law but rather interconnected with it. The ongoing acts of many groups, such as First Nation’s peoples’ worldwide, continue to demonstrate sovereignty amidst political, social and economic oppression (Moreton-Robinson, 2007).

In international law, sovereignty is a principle that has ‘internal’ and ‘external (and political)’ aspects (Parry & Grant, 2009, p. 563). Internal aspects of sovereignty consider the person/people who hold the supreme authority within a state and how power is shared within the state. External (political) sovereignty considers the organisation of a state and how it governs and control its own affairs, as well as the potential weakness of a structure, for example if the state can hold power against other countries (Parry & Grant, 2009, p. 563). When reflecting on these concepts of sovereignty, it is also essential to consider how sovereignty exists within the non-human world, such as within ecosystems, at the planetary level, or in the development of technological innovations. From an ecosystem perspective, sovereignty can be understood as the self-regulating mechanism that maintains balance and diversity. These systems within nature operate without human intervention, demonstrating ecological sovereignty.

First nations sovereignty

‘

“If Indigenous sovereignty does not exist, why does it constantly need to be refused?” (Moreton-Robinson, 2007, p. 3)

All Indigenous peoples and groups worldwide will have their own way of defining sovereignty. Indigenous sovereignty came before Western theories, such as social contract theory models by Hobbes, Locke, Hume, and Rosseau (Moreton-Robinson, 2007, p.2). Indigenous sovereignty and rights have often not been written by Indigenous people (Moreton-Robinson, 2007); yet, Indigenous sovereignty remains grounded in resistance to settler-colonial contexts (Cox & Best, 2022; Clavé-Mercier, 2022).

First Nations Sovereignty in Australia and Aotearoa (New Zealand)

Indigenous sovereignty cannot be assumed to be similar (homogenised). First Nations people of Australia and Aotearoa (New Zealand) have unique histories and contexts for how sovereignty is articulated and demonstrated within settler-colonial contexts (Clavé-Mercier, 2022; Cox & Best, 2022). Tino rangatiratanga in te reo Māori (Māori language) is similar to sovereignty or ‘total control’, recognised as exercised by chiefs (rangatira) over all their lands and taonga (everything that is of significance) in Te Tiriti o Waitangi Article 2 [1] (Waitangi Tribunal, n.d.). In Sovereign Subjects, Moreton-Robinson’s (2007) writing on Indigenous sovereignty from an Indigenous perspective is, in itself, an act of sovereignty. Moreton-Robinson (2007, p. 2) considers sovereignty from an Indigenous Australian (First Nations peoples of Australia) feminist perspective to be:

- Embodied: Carried in the body;

- Ontological: Ways of being;

- Epistemological: Ways of knowing;

- Relational: Including complex relations such as those between ancestral beings, humans, and land.

Compared to other forms of sovereignty, Moreton-Robinson (2007) states that Indigenous sovereignty does not seek to dominate over non-Indigenous peoples. For example, as described by Mutu (2010), Māori signatories to Te Tiriti o Waitangi likely understood tino rangatiratanga as enduring despite the British Crown securing kāwanatanga (governance) in Article 1; kāwanatanga was viewed as pertaining to the Queen’s control over her subjects, namely Pākehā (European) migrants and their descendants.

Indigenous peoples’ sovereignty continues to be heavily contested and denied with questions such as, ‘What does embodiment look like?’, ‘How does this align with the dominant (Western) perspectives and politics?’ and ‘How does it align with various Indigenous perspectives and politics?’ Yet this contestation and refusal to acknowledge Indigenous sovereignty often persists without regard for or consideration of how the concept itself is being defined (Moreton-Robinson, 2007).

Critical Self-Reflection Exercise 2

- What does the term sovereignty mean to you?

- Have you heard the term sovereignty before? If so, where, when and why? If you haven’t, why do you think this is the case?

- What is a key takeaway for you regarding Indigenous sovereignty?

Power and domination

Like the Western definition of power above, the Cambridge Dictionary (2023) defines domination as ‘power or control over people or things’. In both definitions, the word over infers a particular expression of power built on force, coercion or control. This inference leads to cultures (personal and professional) that tend to create a ‘dominant’ way of thinking, acting, or characteristics of people. In many cases, individuals or groups who subscribe to these normalised ways of thinking, acting or being, become a dominant group and are afforded power over certain people or things within that context.

Theorists such as Foucault (1991; 1998, 2003) see power as an ever-present instrument often used to enforce domination. Knowledge is often a form of power that reproduces inequality and inequity through different forms of control (MacMillian, 2010).

Impacts of power and domination: privilege

It is essential to understand how different individuals and groups may respond to power and how it is expressed. Within society, these different aspects of power influence the structures that can lead to privilege and disadvantage, including oppression for specific groups.

What is privilege?

Privilege is not separate from power but interconnected with it. It relates to the benefits and advantages that often come in a range of social, economic, or political forms held by the group in power (or the majority) in a society (Garcia, 2015). These are often invisible and unearned and are not just linked to skin colour; they can relate to other cultural aspects that make up a person, such as age, gender, sex, and sexuality (MacIntosh, 2003).

Reflections from the Authors

The word privilege elicits different responses, with people having a very different position and understanding of what privilege is, or even means to them. There are many ways people may consider privilege in their life, or many areas where they may not see where privilege may exist. An everyday example of privilege could be going to a grocery store. What is your experience of a grocery store? Do you feel welcome? Can you find what you’re after or are you able to easily ask for assistance? Can you afford most products?

Privilege is an interesting concept to reflect on, consider, teach and learn. In general conversation, the word itself can elicit a range of different responses. Like racism and other forms of discrimination, everyone comes with a different understanding and experience of what privilege is and can often be viewed as ‘subjective’. Ironically, the invisibility of privilege contributes to these different reasons, understandings and experiences.

We ask you to consider your experience of going to the grocery store. What is your experience of a grocery store? For many of these authors at this current point in time, the grocery store feels like an ‘everyday experience’ borderline a chore rather than a privilege. However, to some, these privileges have not always been afforded, and grocery stores haven’t always felt like ‘everyday experiences’. For some, grocery stores have not been affordable, others the environment isn’t accessible with bright lights and too many sounds that lead to overstimulation. For others, they have been surveilled due to their appearance, often related to their perceived ethnicity, and others have not had the physical means to get to the store, let alone navigate it with physical impairments. It is the unseen aspects of privilege that makes them even harder to acknowledge.

Consider access to grocery stores. In some rural and remote areas, there is not a grocery store. To get groceries, some people need to travel significant distances which requires reliable transport and the financial ability to cover the costs. Some rural and remote areas may have a convenience store, that has groceries air lifted in, once a week, if weather permits. Whereas, urban areas have access to many grocery stores, with fresh produce regularly available. When considering privilege, from the perspective of accessibility to the grocery store, who is privileged? To some extent, does everyone have a level of privilege that there is an option, if all circumstances align, they can go to a grocery store for food? Or are the people who are subsistent farmers, who are not dependent on a grocery store privileged? These simple examples showcase how privilege can be relative, and often unseen as we cannot always see or understand what is happening for others.

Privilege is not…

There are many misconceptions about privilege. However, it is essential to be clear on what privilege is not:

- Privilege is not a one-off event: Privilege is a result of how societies and cultures are built that afford certain privileges and advantages to an individual or group. Privilege derives from the ongoing historical dominance in a society that positions some as dominant over others (MacIntosh, 2003);

- Privilege is not just individual; it is structural: There is a common assumption that privileges that could be afforded to specific individuals and groups have been deserved, earned, or chosen. This assumption is often reduced to socio-economic status and how much a person can afford. Instead, privilege is structural. It is a result of how societies and cultures are built that afford certain privileges and advantages to an individual or group (Cox et al., 2021);

- Privilege is not equal for all people: Due to the structural nature of power, which results in privilege and disadvantage, not all people in the dominant group will experience equal or similar advantages, nor disadvantages. However, privilege creates a form of currency, and if you are part of the dominant group, you have a greater chance of receiving benefits. Alternatively, you may be part of the dominant group and not be aware that you have benefits, as they may feel like ‘a given’ (Garcia, 2015). An analogy to privilege is fish in water. Water to a fish is given. It is part of its environment and cannot be seen, as it is part of its existing survival structure (Morrison, 1993). It is often not until the fish is removed from the water that it realises how connected it has been to the water to survive. Like water, privilege can have benefits and advantages that a person may not see or ever have considered because they may not perceive it to impact on their day-to-day life or they may not have experienced oppressive structures of society;

- Privilege is not binary: Some people often consider privilege a binary construct: you either ‘have it’ or ‘do not have it’. In reality, it is far more complex and challenging to determine privilege sometimes, as the benefits and advantages in society may not be clear. It can be things a person may not have had to think about (Garcia, 2015). Celebrations that are acknowledged with public holidays are a less recognised privilege that people from the dominant culture enjoy for example;

- Privilege is not able to negate adversity: You can still experience other forms of adversity, even if you have not experienced adversity through societal oppression or disadvantage. Likewise, even if you have experienced adversity through oppression and disadvantages, you may also have been afforded privileges.

Impacts of power and domination: intersectionality

What is intersectionality?

Professor Kimberlé Crenshaw first coined the term intersectionality in 1989 (Crenshaw, 1991). Intersectionality can be defined as the complex, cumulative way in which the effects of multiple forms of discrimination (such as racism, sexism, and classism) combine, overlap, or intersect, especially in the experiences of marginalised individuals or groups (Crenshaw, 1991). Similarly, privileges can combine, overlap or intersect, especially for groups with power or those within the dominant cultural group (Crenshaw, 1991).

Compounding disadvantage and the systems that maintain this disadvantage can lead to oppression. For example, the colonial structures within Aotearoa (New Zealand) and Australia, have led to social, political and economic injustice for First Nation’s peoples creating a gap between Indigenous and non-Indigenous peoples, particularly in relation to health.

Why understand intersectionality?

The models discussed by Crenshaw (1989) capture the complexity around discrimination and its compounding nature. It is vital to look beyond standalone social and cultural categories as superior or inferior, leading to forms of privilege and disadvantage. Instead, intersectionality invites us to examine how these social and cultural categories intersect (Guittar & Guittar, 2015). This intersection of many parts of culture (age, race, ethnicity, class, gender, ability, etc.) can lead to certain advantages (power and privilege) or disadvantages (discrimination and oppression) for a person or group. It can also mean that many parts that make up a person or group can increase the advantages or disadvantages that person or group may experience (Shannon et al., 2022).

For example, dominant power structures such as education institutions and health care systems produce and reproduce privilege, disadvantage and marginalisation through a dominant system of values and beliefs; where Western values and beliefs are constructed as the ‘true’ values, and alternative values and beliefs constructed as ‘the other’ (Cox & Best, 2022). For example, the idea of autonomy (or choice) in health care is often viewed from an individual perspective – what does the person want for their own health? This dominant value often ignores historical ideas of autonomy that valued paternalism over individual choice (e.g. the doctor makes the decision for the patient), and other legitimate ways of decision making (e.g. communitarian approaches).

Given the various facets of individuals that are governed by social structures, norms and discourses, it is often the case that people are not entirely privileged or oppressed, but experience privilege in some respects, and disadvantage in others. It is also the case that intersecting identities will likely compound privilege or disadvantage. For example, an Indigenous person who identifies as non-binary and disabled is excluded from fully participating in a society that is designed for able-bodied and heterosexual white people.

How does power (re)produce privilege, disadvantage and oppression?

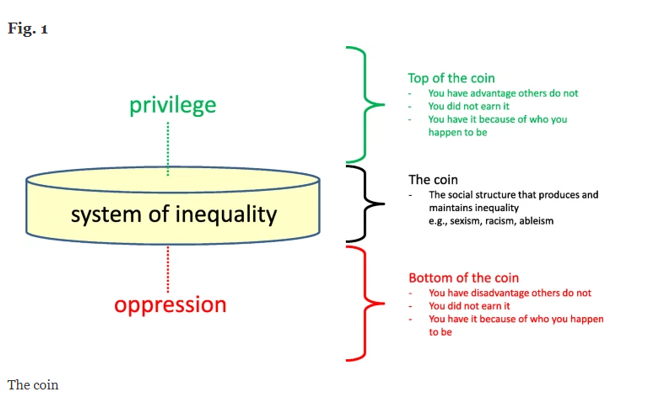

Without understanding power and privilege, people usually do not understand their social position and inherent unearned privileges. This often leads to further disadvantage and marginalising groups already oppressed by the dominant society, by reinforcing what the ‘norms’ are that further exclude certain groups of people. The coin model (Figure 4.1) is a framework for understanding how social systems that lead to forms of discrimination, such as sexism, racism, and ableism, interact with each other to produce complex patterns of privileges and oppression of some groups (Nixon, 2019). The coin symbolises the systems of inequality. It represents discrimination and inequality as unjust social structures that give people unearned privileges and disadvantages (Nixon, 2019). The top side of the coin represents privilege. This includes people who receive advantages from social structures and unfair or unearned benefits due to their ways of being valued by others, whether because of their racial, cultural or other privileges. The bottom side of the coin represents oppression. This includes people who are made up of the most disadvantaged and vulnerable groups in society, such as specific high-risk groups, communities with identified needs, and lower socioeconomic groups (Nixon, 2019).

Unlike intersectionality, Nixon’s (2019) coin analogy specifically states,

“A single coin does not represent all privilege or all oppression. Rather, each coin represents a specific system of inequality (e.g., sexism, racism, ableism). Each person typically occupies the position on the top of some coins and the bottom of other coins at the same time.”

However, each coin that represents each social structure highlights internal asymmetries which may benefit some, but not others (Nixon, 2019).

Impacts of power and domination: oppression

Oppression is an ongoing process ‘in which people are governed unfairly and cruelly and prevented from having opportunities and freedom (Cambridge Dictionary, 2023). A non-exhaustive list of ways oppression manifests, and may overlap, includes:

- Exclusion: Unjustly excluded from social groups based on particular membership conditions (Richardson, 2023). This exclusion leads to forms of discrimination against individuals or groups of people, such as racism, sexism and ableism (Crenshaw, 1991; Nixon, 2019). For example, many buildings (both public and private) are designed in certain ways which actively exclude some body types;

- Exploitation: Unfairly using someone or something to their advantage. Overt examples of exploitation include systems of oppression worldwide, particularly in the treatment of Indigenous lands and peoples (Moreton-Robinson, 2004). More covert ways of exploitation include cultural (in)appropriation;

- Surveillance: Foucault defines surveillance as the ‘watching, counting and categorising of people’ (as cited in Gutting, 1984). However, a contemporary definition by Cambridge Dictionary (2023) states that surveillance is ‘the act of watching a person or place, especially a person believed to be involved with criminal activity or a place where criminals gather’. The contemporary definition extends this seemingly innocent – abacus approach to monitoring a person to showcase that surveillance is directly related to criminality. These acts of surveillance can be both overt and covert;

- Sanctioned violence: Violent acts against people supported by the law (Moreton-Robinson, 2004). Sanctioned violence is not limited to physical acts of violence towards an individual. It can be systemic towards a group of people. A key example of this would be the disproportionate incarceration rates, and over-representation of Aboriginal, Torres Strait Islander (Watego et al., 2021) and Māori people in the justice system (Ministry of Justice, n.d.);

- Silencing: Denying individuals or groups the ability to speak freely or undermining the validity of their claims. There are substantial attempts to silence critical race theories and other forms of ways of knowing, being and doing that threaten to address forms of oppression within society. This silencing occurs through how the media reports or does not report on certain topics particularly pertaining to people of colour;

- Erasure: Ignoring or attempting to remove histories (Richardson, 2023). For example, in Aotearoa, silencing Te Tiriti was an attempt to erase Māori history from the national narrative (Seuffert, 1998). This process ignores the sovereign power of Indigenous peoples, as acknowledged in the United Nations Declaration of Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP, 2007).

Overlapping acts of oppression lead to significant and intergenerational impacts on oppressed individuals and groups and are ultimately a determinant of their overall health.

Power and resistance

Resistance or opposition to the dominant norms within society has been demonstrated throughout history in many different examples, including that of Indigenous peoples worldwide (Watego et al. 2021). Challenging the status quo including dominant norms, cultures and groups can be extremely difficult, and may be mounted at two different levels:

- Micro resistance: individual level;

- Macro resistance: political level.

Many acts of resistance can be considered on both a micro (individual) level and a macro (political) level. For example, the landmark case in Australia where Ophthalmologist Associate Professor Kris Rallah-Baker, a Yuggera, Warangoo and Wiradjuri man, brought forward claims of culturally unsafe, insulting and offensive treatment towards him by another practitioner to the Australian Health Practitioner Registry Association (Australian Health Practitioner Registry Association, 2023). This demonstrates micro resistance, as he spoke up against discriminatory behaviour which has often been considered a norm. It also demonstrates macro resistance, as this has become a landmark case which has impacted legislation for practitioners in Australia leading to structural change. Another example is Irihāpeti Ramsden, Māori nurse and scholar, who first introduced Cultural Safety. Her thesis was an individual act of resistance speaking out against the dominant norms within nursing and health care (Ramsden, 2002), that has led to systemic change beyond nursing to address power and power structures (Cox et al.,2021).

Resistance to the dominant group

Resistance to the dominant group, and challenging dominant norms has been showcased throughout history. Knowledge is a source of power. Knowledge, such as Indigenous Knowledges surrounding relationality and positionality have resist dominant power relations, and the dominance enacted over groups of people. This knowledge about resisting dominant powers has been advanced through many different avenues. Resistance often comes from individuals and groups outside the dominant group who experience inequality and inequity through social, political, and economic structures and rally against these.

Resistance by the dominant group

For the dominant group, the idea of resistance to the status quo can play out in two different ways:

- Resistance to change: Some dominant groups are resistant to addressing forms of inequality, disadvantage, and oppression. They are resistant to change, with attempts to maintain the norm;

- Resistance in order to create change: To address forms of inequality, disadvantage, and oppression the dominant group can resist the dominant cultures and/or groups they have been part of. Creating change, in line with the principles of Cultural Safety requires critical self-reflection on individual and systemic levels. It requires knowledge of one’s social positioning and privileges, which can allow for transformative thinking and behaviours by those with membership in the dominant social identity (Cox et al., 2021). It requires the dominant group to involve themselves in truth-telling, learning, and acknowledging how their ways of knowing, being and doing produce and reproduce unearned privileges.

Therefore, knowledge, as power, has the potential to be both transformative and an instrument that reproduces inequality.

Critical Self-Reflection Exercise 3

- What has it been like to read about the idea of resistance to the dominant group?

- What thoughts, feelings or ideas have come up for you? Do these align with resistance against the dominant norms or resisting to challenging the dominant norm?

- What ways have your resisted power in the past? For example, what actions did you take? What allowed to to support change? What were the barriers to supporting change?

There are endless examples of macro and micro forms of resistance against dominant powers, including acts of resistance by Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and Māori people.

- Do you know of any examples (historical or contemporary) that demonstrate resistance to dominant cultures within the health care system?

References

Ardill, A. (2013). Australian Sovereignty, Indigenous Standpoint Theory and Feminist Standpoint Theory, Griffith Law Review, 22(2), 315–343, https://doi.org/10.1080/10383441.2013.10854778

Australian Health Practitioner Regulation Agency (2023, November 02). Doctor banned for discriminatory and offensive behaviour. https://www.ahpra.gov.au/News/2023-11-02-Doctor-banned-for-discriminatory-and-offensive-behaviour.aspx#:~:text=Landmark%20outcome%20supports%20goal%20to%20eliminate%20racism%20from%20Australian%20healthcare.&text=ACT%20doctor%20banned%20over%20discriminatory,in%20cases%20of%20professional%20misconduct.

Avelino, F. (2021). Theories of power and social change. Power contestations and their implications for research on social change and innovation, Journal of Political Power, 14(3), 425–448, https://doi.org/10.1080/2158379X.2021.1875307

Bond, C. J., Singh, D., & Tyson, S. (2021). Black Bodies and Bioethics: Debunking Mythologies of Benevolence and Beneficence in Contemporary Indigenous Health Research in Colonial Australia. Journal of Bioethical Inquiry, 18(1), 83–92 https://doi.org/10.1007/s11673-020-10079-8

Clavé-Mercier, V. (2022). Politics of Sovereignty: Settler Resonance and Māori Resistance in Aotearoa/New Zealand. Ethnopolitics, 23(1), 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/17449057.2022.2096767

Cox, L., & Best, O. (2022). Clarifying Cultural Safety: its focus and intent in an Australian context. Contemporary Nurse, 58(1), 71–81. https://doi.org/10.1080/10376178.2022.2051572

Cox, L., Taua, C., Drummond, A., & Kidd, J. (2021). Enabling Cultural Safety. In J. Crisp, J. Crisp, C. Douglas, G. Rebeiro, & D. Waters (Eds.), Potter & Perry’s fundamentals of nursing (6th ed., Australia and New Zealand edition, pp. 49–83). Elsevier Australia

Crenshaw, K. (1989). “Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics.” University of Chicago Legal Forum 1989(1), Article 8. http://chicagounbound.uchicago.edu/uclf/vol1989/iss1/8

Curtis, E., Jones, R., Tipene-Leach, D., Walker, C., Loring, B., Paine, S.-J., & Reid, P. (2019). Why Cultural Safety rather than cultural competency is required to achieve health equity: A literature review and recommended definition. International Journal for Equity in Health, 18(1), 174–174. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-019-1082-3

Dahl, R.A. (1957). The concept of power. Behavourial Science, 2(3):201-15. https://doi.org/10.1002/bs.3830020303

DiAngelo. (2018). White Fragility: Why it is so hard for White people to talk about racism. Beacon Press.

Domination (2024). In Cambridge English Dictionary. Cambridge University Press. https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/domination

Foucault, M. (2003). Le pourvoir psychiatrique [Psychiatric power]. Seuil. Paris.

García, J. D. (2015). “Privilege (Social Inequality).” Salem Press Encyclopedia. Salem Press.

Guittar, S.G., & Guittar, N.A. (2015). Intersectionality. In International Encyclopedia of the Social & Behavioural Sciences (pp. 657-662). Retrieved February 20, 2017 from https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-097086-8.32202-4

Gutting G. (1994). The Cambridge companion to Foucault. Cambridge University Press.

Harris, P., Baum, F., Friel, S., Mackean, T., Schram, A., & Townsend, B. (2020). A glossary of theories for understanding power and policy for health equity. Journal of epidemiology and community health, 74(6), 548–552. https://doi.org/10.1136/ jech-2019-213692

Little, A. (2020). The Politics of Makarrata: Understanding Indigenous-Settler Relations in Australia. Political Theory, 48(1), 30–56. https://doi.org/10.1177/0090591719849023

Lukes, S. (2005). Power: A Radical View, second expanded edition. London: Macmillan.

Macmillan, A. (2010). Foucault’s history of the will to knowledge and the critique of the juridical form of truth. Journal of Power. 3(3). 365–384. https://doi.org/10.1080/17540291.2010.524992

Maddison, S. (2009). Black Politics: Inside the complexity of Aboriginal political culture, Crows Nest, N.S.W.: Allen & Unwin.

Marshall, H., Douglas, K. & McDonnell, D.. (2006). Deviance and social control: who rules? South Melbourne: Oxford University Press.

McCammon, R.C. (2018, November 8). Domination. In E.N. Zalta (Ed.) Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy, (Winter 2018 Ed.) . https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/ win2018/entries/domination/

McIntosh, P. (2003). White privilege: Unpacking the invisible knapsack. In S. Plous (Ed.), Understanding prejudice and discrimination (pp. 191–196). McGraw-Hill.

Ministry of Justice (n.d.). He Waka Roimata Transforming Our Criminal Justice System First report of Te Uepū Hāpai i te Ora- safe and effective justice advisory group. https://www.justice.govt.nz/assets/Documents/Publications/He- Waka-Roimata-Report.pdf [PDF]

Moreton-Robinson, A. (2004). Whitening Race: Essays in social and cultural criticism. Aboriginal Studies Press. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/qut/reader.action?docID=287025

Moreton-Robinson, A. (2007). Sovereign Subjects: Indigenous Sovereignty Matters. Allen & Unwin, New South Wales.

Moreton-Robinson. (2015). The white possessive: property, power, and Indigenous sovereignty. University of Minnesota Press.

Morrison, T. (1993). Playing in the dark : whiteness and the literary imagination. New York :Vintage Books.

Mutu, M. (2010). Constitutional intentions: the treaty texts. In: Mulholland M, Tawhai V, (Ed.) Weeping waters: the Treaty of Waitangi and constitutional change. Wellington: Huia; pp. 13–40.

Nixon, S.A. (2019). The coin model of privilege and critical allyship: health implications. BMC Public Health 19(1637) https://doi.org/ 10.1186/s12889-019-7884-9

Oppression (2024). In Cambridge English Dictionary. Cambridge University Press. https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/oppression

Parry, C., Grant, J. P., Barker, J. C., & Parry, Clive. (2009). Parry & Grant Encyclopaedic Dictionary of International Law (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press.

Power (2024). In Cambridge English Dictionary. Cambridge University Press. https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/power

Puzan, E. (2003). The unbearable whiteness of being (in nursing). Nursing Inquiry, 10(3), 193–200. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1440-1800.2003.00180.x

Ramsden, I. (2002). Cultural Safety and Nursing Education in Aotearoa and Te Waipounamu, in Nursing. Victoria University of Wellington: Wellington. https://www.croakey.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/RAMSDEN-I-Cultural-Safety_Full.pdf [PDF]

Richardson, K., (2023). “Exclusion and Erasure: Two Types of Ontological Oppression”, Ergo an Open Access Journal of Philosophy 9(23) 603-622. https://doi.org/10.3998/ergo.2279

Seuffert, N. (1998). Colonising concepts of the good citizen, law’s deceptions, and the Treaty of Waitangi. Law, Text, Culture, 4(2), 69–104. https://search.informit.org/doi/10.3316/agispt.19991615

Shannon, G., Morgan, R., Zeinali, Z., Brady, L., Couto, M. T., Devakumar, D., Eder, B., Karadag, O., Mukherjee, M., Peres, M. F. T., Ryngelblum, M., Sabharwal, N., Schonfield, A., Silwane, P., Singh, D., Van Ryneveld, M., Vilakati, S., Watego, C., Whyle, E., & Muraya, (2022). Intersectional insights into racism and health: not just a question of identity. The Lancet, 400(10368), 2125–2136.https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(22)02304-2

Smith, A., Crosthwaite, J., & Clark, C. (2014). White privilege. In S. Thompson (Ed.), Encyclopedia of diversity and social justice. (pp. 743-744) Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. https://ebookcentral.proquest.com/lib/qut/detail.action?docID=1920943.

United Nations (General Assembly). (2007). Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People. https://humanrights.gov.au/our-work/ un-declaration-rights-indigenous- people#:~:text=Listen,the%20rights%20of%20Indigenous%20peoples. [PDF]

Waitangi Tribunal. (n.d.). Section 3: The signing of the Treaty of Waitangi. https://waitangitribunal.govt.nz/publications-and- resources/school-resources/treaty-past-and-present/section-3/

- [1] Te Tiriti o Waitangi is the Māori language text of the Treaty of Waitangi (English text). The two texts are not equivalent, and there are some notable differences. Following the international law rule of contra proferentum, where there is ambiguity in such texts, it is recommended practice to read against the offering party, in this case, Te Tiriti o Waitangi (Mutu, 2010). ↵

Critical theory at its most basic seeks to understand and change imbalanced relations of power and domination.