Culture and Cultural Safety

Mary-Claire Balnaves and Shelley Hopkins

Cultures are created by and between people who interact within a particular environment. Everyone has their own personal culture; an individual’s cultural identities co-exist with professional, organisational and societal cultures.

Personal culture

Culture is a dynamic construct, continually constructed and reinforced by those around us. We are not born ‘with’ culture rather we are born into cultures.

Consider how distinct aspects of your being and identity are emphasised depending on the context you are in, who else is there and what is happening. At times ethnicity may be emphasised, at other times gender identity, sexuality, professional identity, class or ability. Culture refers to multiple aspects of our identity including but not limited to age, class, socio-economic status, ability, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, and education.

Reflections from the authors:

Every day, culture is practiced and created. For example, when teaching and learning at university, each class creates and practices its own culture. This culture will be shaped by the room you are in and how it is set up. It will shift with who is in the room, what content is being discussed, and how people engage. It may include very dominant perspectives or provide space for diverse opinions and ideas. Any change to content, instructor, learners or the space can influence the learning and teaching culture of that class.

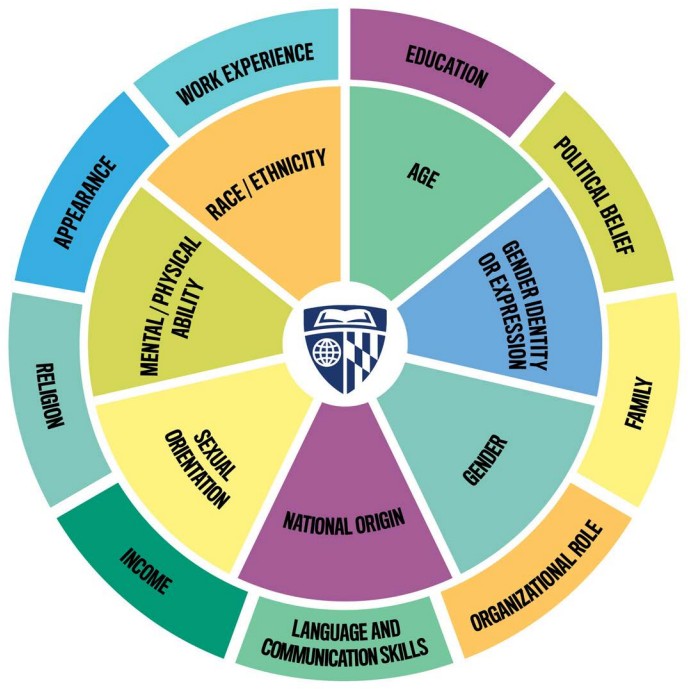

The Diversity Wheel below (Fig. 3.1 Johns Hopkins University) demonstrates the components of culture that may change over time (outer portion of the wheel) versus cultural identities that are more permanent and/or more visible (inner portion).

Culture also refers to our way of life, our social experience of belonging, status and opportunity and is expressed in our beliefs, values, attitudes. It influences the assumptions that we use to make decisions and respond to situations every day, including in our personal and professional lives.

Personal culture through the lens of Cultural Safety

Culturally safe individuals understand that there is as much variation within personal cultures, as between them. For this reason, it is not possible to learn all cultural variations. Some people often assume Cultural Safety is learning about a person’s cultural traditions, often material traditions, like dress, food, language, significant days of celebration etc. This approach to culture infers it is similar to a ‘recipe’, easily learnt and applied for anyone you see to fit that culture. This approach, often labelled as cultural competency, tends to use and reinforce stereotypes and does not consider that each person is an individual, even if they share a similar culture to someone, they may have different and unique ways of knowing, being and doing.

Culturally safe practice accepts that the individual is the expert on their own cultural needs. Cultural Safety supports good practice by power sharing, negotiation and working in partnership as it focuses on the unique needs of each person. This practice supports each individual to communicate their needs in a safe, respectful and trusting space and promotes listening rather than assuming. Cultural Safety asks individuals in positions of power (e.g., lecturers, student group leaders, health professionals) to use critical self-reflection, to examine ways to shift their power so that power and responsibility can be shared.

Example

It is easy to assume that the people with whom we work or study with as colleagues, share the same values, beliefs, attitudes, assumptions, privileges, social status and social experience. Likewise, an assumption could be that everyone has the same sense of belonging in a university and of feeling trusted and respected.

However, not everyone enjoys the privileges associated with a sense of belonging that comes with being part of the majority or dominant cultures.

Culturally safe individuals reflect on and understand their personal and professional cultures and the impacts these have on their experiences in different environments and their interactions with other individuals (students, colleagues, teaching staff).

Professional and organisational culture

Professional and organisational cultures are the beliefs, values, priorities, sensibilities, ways of doing business, protocols, knowledge, jargon/language that exist within a profession or an organisation.

In Australia, an example of professional culture is the adoption of the Western biomedical model of health. This model conceptualises health as the absence of disease or illness which is considered the dominant culture in health. It generally places value on the body as a machine, individualistic ways of thinking, health as only predominantly physical, and cure over care. This differs significantly from the non-Western models of health and wellbeing that also focus on relationships (with family, friends, community), on interactions with environment and on philosophical and spiritual values (Dune et al, 2021).

Professional and organisational culture through the lens of Cultural Safety

Culturally safe individuals reflect on and understand the cultures of their professions and of the organisations, institutions or settings where they work and the impacts these have on others.

Reflections from the Authors

From our experience as health care professionals, each person accessing health care places different values on their health care encounters. Some people hold strongly the value of relationship building and having a health care professional be interested in who they are and take the time to get to know them as people, rather than just a disease or medical problem. Other people place significance on data and statistics and want to know the current evidence-based research in great detail. More personal aspects of their health or who they are may seem less relevant or unnecessary to share.

Both of these viewpoints, challenge the systems of health care that are often time-poor. Cultural Safety allows health professionals to see where they can adjust their practice to consider the person’s individual needs (e.g. chatting to a person about their personal life whilst completing a clinical task, or printing out research before the person comes in) and advocate for system changes (e.g. flexibility of appointment times).

Cultural Safety is applicable in all situations. Every interpersonal situation involves several cultures. It involves the culture of the individual, the culture of the profession we are working with, it occurs in the organisational cultures and within the broader societal culture.

Examples

As members of a workforce, we may take for granted or overlook the power imbalance that exists between us and service users such as students, customers, clients or patients. We become insiders to the cultures of our professions and workplaces and thus hold significant power over others. This power exists in terms of knowledge and status.

Cultural Safety brings these dynamics to mind enhancing our capacity to focus on the needs of those with and for whom we work.

Unsafe cultural practices are actions which diminish, demean or disempower the cultural identity and wellbeing of any individuals, including colleagues and service users. Forms of discrimination such as racism and sexism are examples of culturally unsafe practices.

Societal culture

Our social experience and our personal, community and nations’ histories are part of who we are as cultural beings. People and society co-create each other’s culture. That is to say, the society and communities we live in are the cultures we are socialised into. The people we become influence the culture of society through our actions. The theory that explains this effect is known as ‘social constructionism’ and this underpins Cultural Safety.

Reflections from the Authors

As students and registered health care professionals, there is often an assumption that we are knowledge holders and somewhat ‘experts’ in health care. This social construction makes sense, as generally the public expects that health professionals will have training, knowledge and understanding of health and the health care system. Cultural Safety challenges this social construct, as it puts the person receiving care as a knowledge holder of what is best for their health, even if they do not have any formal health education or training.

Societal culture through the lens of Cultural Safety

While there are variations in the cultural ways of our society, there are also dominating aspects of the society. These aspects can be considered as the dominant culture.

Global declarations, national policies and laws aspire to respect and ensure equity in relation to aspects of culture discussed in this module such as age, ability, ethnicity, gender, and gender identity. Cultural diversity is valued and those from non-dominant cultures should not be disadvantaged. However, many from non-dominant cultures have poor health and social outcomes and suffer significant disadvantage in Australia. This is not due to any difference inherent in the people but in how society supports these cultures.

Examples

While Australia and Aotearoa (New Zealand) are considered secular and multi-faith societies, the Christian religion dominates cultural norms. For example, in Australia, many of the public holidays are centred around Christian religion (e.g. Easter, Christmas).

While it is considered multi-cultural, the English language dominates and ways of doing business throughout society and are based on European knowledges, philosophical traditions, pedagogical practices, and medical practice.

Critical Reflection Exercise 1

Reflect on the different cultures that impact on you in your personal and professional lives, by answering the following questions.

Be curious about the thoughts, ideas, feelings, emotions that come up during your reflection. These can be key pieces of information to explore and consider their source. There are no ‘correct’ ways to feel or think. There will be diverse viewpoints. On-going self-inquiry takes time, non-judgement, and exploration.

- Write down at least three cultures that you identify with. These may be your religious or spiritual culture, your ethnicities, your professional culture, your generation, your gender.

- Write down as many norms or rules you can think of that are part of the cultures you identified.

- What cultures exist within your university, your faculty, your school, centre, hospital or clinic?

- What are some of the norms or rules that govern your professional interaction with colleagues, students and/or clients or patients?

- How did you learn the norms or rules of one your cultures?

Having reflected on the diversity of cultures to which you belong, and how these impact on your interactions with others, let us consider principles that allow people to feel safe, respected, and valued.

Cultural Safety

Cultural Safety is about power sharing, negotiation, flexibility, and openness to various ways of knowing, ways of producing knowledge and ways of applying knowledge. It includes:

- Cultural self-awareness. This acknowledges that we all have culture. We have culture as individuals and are part of groups that have culture. We are also a part of organisational and societal cultures;

- Cultural sensitivity. This acknowledges that there are differences between cultures and that these differences are legitimate;

- Cultural Safety. This is an outcome of self-reflection on aspects of our cultural lives, which allows for power sharing, trust and enables partnerships. It gives power to service users from service providers.

Culturally safe practice is an ongoing process. It requires critical reflection by individuals on their personal, professional and organisational cultures and the dimensions of power that exist within their different cultural identities. It is important as often, it can be easy to see our way as ‘normal’ or ‘right’, particularly if parts of who we are align with dominant societal cultures.

Cultural Safety examines individuals’ socialisation which can produce unhelpful attitudes and actions towards those considered different to themselves (Ramsden, 2002). Culturally safe individuals acknowledge the impact their values, assumptions and biases can have on others’ experiences with a service or organisation, and with them personally. This self-reflective work is essential for respectful interactions and to gain and maintain trust. It forms the basis of working partnerships. Cultural Safety provides a way to effectively work within teams to ensure people are not diminished, demeaned, or disempowered on an individual level (e.g. discriminated against based on race, gender, age etc.) or organisational level (e.g. policies that exclude – overtly or covertly – based on race, sex, gender etc.). Cultural Safety is an outcome that is defined by those with whom we work, teach or who participate in research projects.

Cultural Safety in universities

Universities have evolved from Western knowledge systems which dictate what types of knowledge are considered valid and marginalise the voices and knowledges outside the dominant Western system. For example, going to a lecture at university often includes students sitting in a large theatre, with seats facing forward towards the instructor, positioning them as the expert or knower. Whereas some Indigenous methods of learning and teaching use methods like yarning circles, which place everyone, both instructor and students, in a circle, with everyone having an equal right to contribute and share knowledge.

A Cultural Safety approach encourages an examination of these assumptions and an openness to exploring other knowledge systems within our disciplines. These are early steps in decolonising education by recognising that these assumptions exist and impact on what knowledge is valued and shared.

We can apply a Cultural Safety lens to the tertiary education context to think about the social determinants of access to tertiary education and issues of retention.

In Australia and Aotearoa (New Zealand), success at school is linked to the individual’s and school’s socio-economic status:

- Individuals with tertiary educated parents are more likely to complete tertiary education than those without tertiary-educated parents (Equity-in-Education-country-note-Australia).

- Students from socioeconomically disadvantaged backgrounds may lack support and opportunities for adequate preparation for university study.

- Geographical location and financial issues can impact on access to university, or the resources such as computers and internet needed to be successful during a student’s time at university.

- Unfamiliar social or cultural norms of the tertiary classroom setting can serve to exclude students from full participation in learning. For example, students who complete group assignments may have different expectations of working in a group, or the desired outcome.

Such fundamental structural inequalities can present barriers and foster poor performance or self-exclusion by students. Adjusting to new places, people and practices can cause feelings of being out of place, anxiety, confusion, frustration and doubt, and culturally safe individuals (students, colleagues, and teaching staff) can assist students in addressing and overcoming these feelings.

Reflective practice enables awareness of and empathy towards these experiences and feelings. Cultural Safety challenges individuals to acknowledge and negotiate power imbalances to address racism, stigma, and discrimination in society, in our professional roles (teaching, research and student support) and in our everyday lives.

Examples

Professional and institutional cultures impacting on practice:

- Looking for apology after ‘whitesplaining’ response to Indigenous eye doctor | NITV (sbs.com.au)

- Racism in universities is a systemic problem, not a series of incidents | Kehinde Andrews | The Guardian

- Racism and the Tertiary Student Experience in Australia | Adam Graycar (2010) | Australian Human Rights Commission [PDF]

- Students face ‘confronting’ levels of racism | ANU

- Researchers say racism is costing the Australian economy billions | ABC News

- #MeTooPhD reveals shocking examples of academic sexism | The Guardian

- At 93, Australia’s oldest university student is busier than ever The Sydney Morning Herald

- Māori doctor Espiner, Emma, (2023) E-Tangata

Critical Reflection Exercise 2

Reflect on a professional interaction you had with a student, research participant, colleague, client or patient where you felt uncomfortable with your reaction to them or with the decisions you made:

- What were your thoughts, feelings, ideas, beliefs, and values going into the interaction, during the interaction and after the interaction?

- What did you learn about yourself?

- How could you approach it differently in the future?

Strategies for culturally safe practice

Reflection is a key strategy of Cultural Safety. It is an on-going process of reflecting on self, one’s own culture and profession. This includes considering the power and privilege, attitudes, assumptions and beliefs about others that may be inherent in these cultures.

Strategies for culturally safe practice include:

- Practice critical self-reflection on your culture/s. What cultures make up who you are? Who and what has influenced your cultural identities and perspectives so far? What do you consider to be ‘normal’?

- Being knowledgeable about history and current social issues. Examining the power dimensions represented in these historical events and current issues. Thinking about the impact of these power dimensions on the lives of those who are not privileged by these power dimensions;

- Consider the knowledge that forms the core understanding of your discipline. How has this knowledge been developed? Were there particular voices that were privileged in the development of this knowledge? Read the history of your discipline with a critical lens. Can this understanding have an impact on your teaching and research?

- Applying active listening skills so you are really hearing and checking your understanding of others’ views in your interpersonal interactions;

- Actively negotiating knowledge and outcomes through respectful relationships and partnerships with others to develop trust and power sharing.

Critical Reflection Exercise 3

Adopting a flexible and open-minded approach, use the following techniques to develop a culturally safe practice.

Reflect upon and examine your attitudes towards health.

- When you hear the term ‘health’, what does that mean to you?

- Has your attitude towards health changed over time, or has your personal experience with health changed?

- What are the facilitators and barriers of your attitudes and beliefs when working with people who are experiencing poor health?

Consider how power operates between you and a person (student/patient/colleague) who is experiencing poor health.

- How does the balance of power look?

- Are you in a position of power?

- How can power sharing be negotiated?

Further reading for educators

Kurtz, D. L. M., Janke, R., Vinek, J., Wells, T., Hutchinson, P., & Froste, A. (2018). Health Sciences Cultural Safety education in Australia, Canada, New Zealand, and the United States: a literature review. International Journal of Medical Education, 9, 271–285. https://doi.org/10.5116/ijme.5bc7.21e2

Merritt, F., Savard, J., Craig, P., & Smith, A. (2018). The ‘enhancing tertiary tutor’s Cultural Safety’ study: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultural training for tutors of medical students. Focus on Health Professional Education: A Multi-Professional Journal, 19(3), 11–22. https://doi.org/10.11157/fohpe.v19i3.238

Sanderson, C. D., Hollinger-Smith, L. M., & Cox, K. (2021). Developing a Social Determinants of Learning™ Framework: A Case Study. Nursing Education Perspectives, 42(4), 205–211. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.NEP.0000000000000810

Wilkinson, A. et al. (2023) Acknowledging colonialism in the room: Barriers to culturally safe care for Indigenous Peoples. International Journal of Critical Indigenous Studies. 15(2), 143–159. https://doi.org/10.5204/ijcis.2614

References

Dune, T., McLeod, K., & Williams, R. (Eds.). (2021). Culture, diversity and health in Australia: Towards culturally safe health care. Routledge.

Johns Hopkins Carey Business School. (2021). Roadmap for Diversity, Equity, Inclusion, and Belonging. https://carey.jhu.edu/sites/default/files/2021-06/2021-2-497-roadmap-deib_v3b.pdf [PDF]

Ramsden, I. (2002). Cultural Safety and Nursing Education in Aotearoa and Te Waipounamu, Wellington: Victoria University. https://www.croakey.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/RAMSDEN-I-Cultural-Safety_Full.pdf [PDF]

Curriculum resources

Social constructionism refers to a group of social theories that consider the relationship between people and society, often sourced to the work of Peter Berger and Thomas Luckmann 's The Social Construction of Reality (1966). It argues that society creates people and that people create society. It considers the way that society creates gender, ‘race’, age for example along with ideas of health. Social constructions affect human beings. Socially created assumptions circulate; influence the way people are treated, and how they act. For example, the social construction of men includes that they are tough, logical, strong resulting in some not seeking health care as readily as women do, probably contributing to the fact that statistically they die earlier.

Socialisation is the process occurring throughout childhood whereby children learn values, beliefs and attitudes and how to act in their context. Families, schools, peers, the mass media and society are socialising agents. When we enter professions, we undergo ‘secondary socialisation’ where we learn the rules, norms, values, beliefs and priorities of the profession.

Race is a social construct not a scientific fact as biologically there is only one human race. Some groups however identify with a notion of race since they have always be catergorised according to an assumed race. They reclaim it as a positive social and cultural identifier.