3.4 Disability and critical health psychology: Applications for work and everyday life

Rebekah Graham and Kathryn McGuigan

Overview

Historically, critical health psychology has not treated disability equitably and has tended to erase disability spaces from texts and exemplars. This chapter is one step towards addressing this oversight. We provide practical suggestions for ways in which practitioners of critical health psychology (and anyone) can apply critical health psychology ideas and approaches in everyday work and home life. It also provides a starting point for addressing systemic changes. Firstly, we explore the history of disability and review different models of disability. The chapter then moves to defining ableism and considers how taking a critical health psychology approach provides opportunities to address ableism. Following this, the chapter focuses on Aotearoa New Zealand and contemporary disability practice. Indigenous approaches are discussed with examples from Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders and Māori. Lastly, the chapter reflects on the intersections with marginalised groups and provides examples from specific disability communities (Blind/low vision, Neurodivergent, chronic illness and Rainbow communities experiences with disability). The question we address in this chapter is: “can critical health psychology practitioners use disability theories and models in practice”?

Learning objectives

- Explore this history of disability and review three different models of disability.

- Recognise ableism and start to consider how critical health psychology might provide opportunities to address ableism.

- Explore disability in Aotearoa New Zealand including Indigenous approaches.

- Review case studies to explore disability work in practice in the community.

Critical health psychology and disability

There has been a consistent lack of attention paid to disability by critical health psychology and psychology in general, with a few exceptions (Quirk, 2022). A focus on the biomedical approach to disability has resulted in psychological research undertaken from a deficit-oriented lens and an individualistic approach to disability, tending to exclude disabled people and focusing on overcoming impairment, which can be damaging (Goodley et al., 2017). There has been even less work with Indigenous approaches to disability. In contrast, a critical health psychology approach emphasises the importance of integrating and incorporating disabled people and families throughout. Critical health psychology is also grounded in grassroots activism, advocacy groups, organisations, and movements, that support work that addresses equity, systemic and structural barriers, and the role of the social determinants of health. Critical health psychology tends to also take an intersectional approach when working in health.

Globally, there have been and remain ongoing calls for disabled persons worldwide to have self-determination with regard to decision making (Charlton, 1998; Wong, 2020). The phrase “nothing about us without us” reflects this clear call from the disability community. Self-determination is a core orientation for critical disability studies, which utilises the socio-political construction of disability in arguing for the full social inclusion of disabled persons (Meekosha & Shuttleworth, 2017). However, while the discipline emphasises the need for social change to challenge systemic inequalities and social exclusion, understandings of disability are from a predominantly Western worldview (Goodley et al., 2019; Smith & Routel, 2010). Both self-determination and dignity are guaranteed rights for disabled persons under the United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD). The purpose of the UNCRPD Convention is to promote, protect, and ensure the full and equal enjoyment of all human rights and fundamental freedoms by all persons with disabilities, and to promote respect for their inherent dignity (UNCRPD, n.d).

History of disability in New Zealand

Approaches to disability in Aotearoa New Zealand have been influenced by wider sociocultural trends in Western nations. At the turn of the 20th century the prevailing Western approach to disability was biomedical (Quirk, 2022). Intellectual disability and mental health were poorly understood within this framework. This biomedical framing intersected with and supported the concurrent eugenics-based belief systems (Turda, 2022).

What is eugenics?

Eugenics is a philosophy that advocates controlling reproduction to produce better offspring. It flourished in the early 1900s but lost credibility after the Nazis’ horrifically extreme version of eugenics in the Second World War. Organised New Zealand eugenics groups in the early 1900s advocated sterilising those they deemed ‘unfit’ to breed. They urged upper-class and middle-class women to stop using contraception and to breed more, to stop the country being dominated by ‘defectives’ (Tolerton, 2011)

Eugenics is a value system that determines a person’s value according to biological, social, and cultural boundaries. Insiders, who belong to the valued race-based group, are viewed as separate from outsiders, who are framed as potential enemies of the race (Turda, 2022). In Aotearoa New Zealand, one example of eugenics-based practice in the early 20th century was the founding of the Plunket Society. Truby King founded Plunket in 1907 in order to improve the fitness of Caucasian New Zealand babies. Dr King was a member of Dunedin’s Eugenics Society, assisted in the management of Seacliff Asylum, and went on to become New Zealand’s Inspector General of Health. He wrote, in 1912, “The destiny of the race is in the hands of its mothers” and advocated strongly for scheduled feeding, exposure to sunlight, and cleaning. Truby King claimed that asylum admittance was a result of poor feeding and claimed that “Education in parenthood offers, I submit, the main hope for the reduction of insanity.”

Western psychology has been, and continues to be, influenced by eugenics-based beliefs. Gould (1996) detailed the development of empirical practices in psychology to support eugenics and racism in his book, The Mis-measure of Man. Eugenics was fundamental to the establishment of empirical methods and behaviourism:

Determinations of what constitutes mental health and human fitness, acceptance of normed assessment and testing practices, minimization of history, social context, or subjectivity, use of animal models of behavior, and focus on self‐control and resilience may be among many eugenics‐related values that remain dominant in Western psycho-therapy practices (Yakushko, 2019, p. 8)

The continued influence of eugenics in Western psychology is most visible in the biologising of human differences, the minimising of social contexts, and the division of individuals into groups according to their supposedly innate characteristics (e.g., intelligence and optimism) (Bergstrom, et al., 2024).

One empirical component linked with eugenics is the idea of “normal”. The concept of a “norm” entered the English language in the mid-1800 and means conforming to or regular (Davis, 2013). To understand disability, it is important to reflect on what constitutes normal and how and why we know this information. American Disability Studies writer and activist Eli Clare positions the use of normal as a tool of oppression, linking it to White Western cultural ideals that value worthiness and wholeness (2017). The concept of abnormality results in individuals being othered and labelled into defined positions, leading to incarceration, institutionalisation, and sterilisation (Clare, 2017). As Annette Malakoff, a disability studies trainee writes, “As one who identifies as disabled, ‘normal’ will probably always make me turn my head and wonder… but I write this in hope of a greater understanding of the potential for negative connotations – and the acknowledgment of my own biases against the word” (Malakoff, 2023). The concept of what is normal is inherently unstable and fluid given that society constantly changes and evolves, but is still holding sway in terms of the body, the medical, and the push to diagnose disabilities (Davis, 2013). Davis argues that we need to continually question the idea of normality and expand into areas such as neurodiversity, chronic illness, and invisible illnesses. This would move us from eugenics (segregation or elimination of difference) to intersectionality, multiple identities, and complexities.

Our task as practitioners of critical health psychology is to create alternatives to—and question the construction of—normalcy, not just to include disability as normal. We can also change our language. The term normal is used in everyday speech, but care needs to be taken to prevent using normal as a type of bias, to exclude others, or to pass judgement.

A combination of eugenics-based values and the dominant biomedical approach, alongside a poor understanding of mental health and limited knowledge of neurodivergence, resulted in legislation being passed in Aotearoa New Zealand that actively removed disabled persons from society. One such example is the Mental Defectives Act, which was passed in 1911. This Act gave the state power to imprison anyone classed as “defective” for as long as the state thought in necessary. At the time, Kai Tiaki, the Journal of the Nurses of New Zealand enthusiastically noted the passing of the bill: “By detention of many such, who out in the world would marry and perpetuate their kind, surely something will be done toward stemming the tide of race deterioration, which fills to overflowing our mental hospitals” (New Zealand Nurses Organisation, 1912, p. 20). A little later, the Education Act (1914) required parents, teachers and police to report “mentally defective” children to the Department of Education and created a School Medical Service to identify “defective” children so they could be subject to surveillance. These punitive approaches continued into the 1920s. A Committee of Inquiry into Mental Defectives and Sexual Offenders (1925) linked intellectual impairment with moral degeneracy and potential sexual offending. The creation of health camps temporarily removed children from their families. The Mental Defectives Amendment Act (1928) created segregated facilities for those imprisoned as a way to “avoid contaminating the race”. These legislative acts and associated segregationist practices remained in place for many decades. The ideas continue to linger and impact on societal attitudes to disability in Aotearoa New Zealand today.

After World War I, the medical and general population of Aotearoa New Zealand became increasingly aware of mental illness and physical impairments due to the experiences of soldiers returning home after war. This shifted the approach from segregation to one of rehabilitation. There was a need for better services, including psychiatric treatment, physiotherapy and plastic surgery. War injuries resulted in the development of improved medical skills such as treatment for burns, plastic surgery and orthopaedics (Figure 3.4.1).

The horrors of World War II also resulted in a reduction in eugenics-based values. Nonetheless, the segregation and institutionalisation of disabled children and adults continued. In 1949, New Zealand parents of children with impairments began advocating for schools and community facilities for their children so they could keep them at home and out of residential institutions—a key recommendation from the World Health Organization. In London, a manifesto published in 1976 called for a change of attitude to disability and disability policy (The Union of the Physically Impaired Against Segregation & The disability Slliance, 1976). The authors challenged the medical model of disability that framed disability as an individual’s problem, and as something wrong or broken that could be cured or contained.

Nonetheless, it took time for attitudes in Aotearoa New Zealand to shift. Disability advocates finally started to see progress in the first decade of the 21st century with the first Minister for Disability Issues, a dedicated office in the Ministry of Social Welfare, and a social-model-based New Zealand Disability Strategy (Stace & Sullivan, 2020). The United Nations Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities (UNCRPD) was finalised in 2006 and ratified by the New Zealand government in 2008. This provided one mechanism for achieving disability rights. The New Zealand government implemented various pieces of rights-based legislation, including the promotion of New Zealand Sign Language as an official language. After a march on Parliament, the last residential institution, Kimberley in Levin, was closed in 2006 (Stace & Sullivan, 2020). The lasting impact of the abuse, cruelty, and harm suffered by those in Aotearoa New Zealand’s residential institutions has been documented in the Royal Commission Inquiry into Abuse in Care. While not limited to disabled children and adults, many of those abused were disabled. The final reports on the abuse and neglect of children, young people and adults in the care of the state and faith-based institutions in Aotearoa New Zealand between 1950 and 1999 are available online and can be downloaded and read in full from the abuse in care website: www.abuseincare.org.nz

Models of disability

Moral

The moral model of disability is a historical framework that interprets disability as a moral failing, as a punishment, or as divine retribution for sins (Tran et al., 2024). This model leads to stigma, shame, and marginalisation for disabled persons and their families (Olkin, 2002). Subsequently, individuals and families may conceal disability (or even the disabled person) to avoid societal judgement and associated stigma. Disability-related stigma continues today and is influenced by a combination of cultural beliefs and the moral model of disability (Jost et al., 2022).

See list below for examples of attitudes and beliefs grounded in the moral model from Courtney Jost (2021):

- disability viewed as a punishment for personal or ancestral transgressions.

- media depicting disabled persons as objects of pity and/or as inspirational figures who have overcome adversity (these narratives reinforce the idea that disability is a personal tragedy, which is an idea grounded the moral model).

- religious attitudes that attribute disability to spiritual causes and associated practices aimed at “curing” the disability through faith-based interventions. These attitudes and beliefs perpetuate the idea that disability is a result of moral or spiritual shortcomings.

- individuals blamed for their disability and/or circumstances.

- segregationist policies and social exclusion. Also rooted in eugenics (see earlier section), with the idea that the moral failing (which led to the disability) must be isolated to prevent contagion.

Critical health psychology practitioners can assist with counteracting these moralistic beliefs and attitudes by:

- promoting the social model of disability (more on this below).

- shifting the focus to societal barriers that prevent or hinder full inclusion.

- facilitating participation in society and foster informed attitudes towards disability.

- advocating for rights-based frameworks, such as the UNCRPD (discussed earlier).

- raising awareness about the context and detrimental effects of the moral model.

Medical

The medical model of disability conceptualises disability in terms of the physical or mental impairment. Essentially, it views disability as a problem located within the individual (Berghs et al., 2016). This is the dominant approach to disability within Western cultures. The medical model characterises disability as deviance from an idealised construction of wholeness (Tran et al., 2024). The main emphasis is on diagnosis, treatment, and cure, with the aim of improving functionality to that considered “normal” (Olkin, 2002). When working within a medical model, health professionals are considered experts and the disabled person and their family are expected to adhere closely to their expert directives or advice. The language of the medical model is clinical and medical, for example, referring to paralysis on the left side of the body as left hemiplegia, or to a spinal injury as a partial lesion at the T4 level. Medical terminology is useful for medical specialists to communicate precisely. It is less useful for determining responses to an injury. Shifting to a medical approach, from a moral one, has led to scientific advancements in treatment. However, this has not necessarily resulted in disability liberation.

A focus on the biomedical approach to disability has resulted in psychological research undertaken from a deficit-oriented lens. Individualistic approaches to disability, excluding disabled perspectives from research, and a focus on overcoming impairment are all damaging to the psychological well being of disabled persons (Goodley et al., 2017). Psychology, within a medical model (a focus on individuals following professional advice, ideas of “curing” illness), has historically had a systematic disregard for disabled people in psychology (Quirk, 2022). The medical model continues to have significant impact on perceptions of disability, and the way in which disabled individuals are treated.

Examples of attitudes, beliefs, and practices grounded in the medical model of disability:

- focusing on the impairment only can lead to pathologising disability. This fosters stigma and discrimination and may result in people viewing disabled persons as “defective”.

- an over emphasis on finding a cure. Prioritising medical solutions can lead to unnecessary medical interventions that have limited success. It can also result in neglecting to address wider social and environmental barriers to inclusion.

- internalisation of medicalised views of deficiency, resulting in poorer mental health, feelings of inadequacy, and reduced social participation.

Critical health psychology practitioners can address the limitations of the medical model by:

- promoting the social model of disability (more below).

- advocating for holistic approaches to health and disability.

- addressing environmental issues and emotional well being.

- shifting societal attitudes.

- engaging in education of communities.

- advocating for the removal of barriers and the fostering of inclusive practices.

Social

The social model of disability was first theorised by Oliver (1982). This represented a significant shift in the theorisation of disability as the focus moved from the “deficient” individual to the role of society, as well as distinguishing between impairment and disability:

Disability is the disadvantage or restriction of activity caused by the political, economic and cultural norms of a society which takes little or no account of people who have impairments and thus excludes them from mainstream activity (Therefore disability, like racism or sexism, is discrimination and social oppression). Impairment is a characteristic of the mind, body or senses within an individual which is long-term and may, or may not, be the result of disease, genetics or injury (Oliver et al., 2012, p. 16)

The social model of disability theorises that it is society that creates disabled conditions through environmental barriers, attitudes, and discrimination. The focus for change shifts to society, which must now ensure accessible structures, work to decrease stigma, and legislate for inclusion (Tran et al., 2024). Disability is constructed as an aspect of a person’s identity, and it is the environment that creates barriers, not the disability (Olkin, 2002). From this perspective, the way to address disability is to change the environment and society (compared to changing the person). Table 3.4.1 highlights the comparisons between the medical and social models.

Table 3.4.1 Comparisons of the medical and social models

| What is disability? | Medical Model | Social Model |

| Implication and impacts | The condition of being unable to perform a task due to impairment, which is an individual burden. | The restriction of activity caused by the design of environments that exclude disabled people from fully participating in society. |

|---|---|---|

| The individual must adjust or become more “normal” to fit into society and the established environments. | Society must adapt the design of environments. Individual differences are normal and accepted. | |

| Eligibility process | Everyone is included | |

| Activities & environments are retrofitted | Inclusive design reduces retrofitting | |

| Segregated or parallel services & experiences | Inclusive strategies minimise segregation | |

| Minimal legal requirement | Best practices for inclusive design | |

| Disabled students, staff, faculty ask to be included | Disabled students, staff, faculty are included by design |

The adoption of the social model has significantly reshaped contemporary perspectives on disability:

- Policy and Legislation: Many countries have integrated the social model into their disability policies, emphasising the removal of societal barriers and the promotion of equal opportunities.

- Educational Reforms: There is a growing emphasis on inclusive education, where learning environments are designed to accommodate diverse needs, reflecting the social model’s principles.

- Public Awareness: Campaigns and media representations increasingly highlight societal contributions to disability, challenging stereotypes and promoting a more nuanced understanding.

While there is positive change, a lot of work remains to be done. Barriers to full inclusion in society persist. These include physical barriers (e.g., steps instead of a ramp, buildings without lifts, public transport that cannot take a motorised wheelchair, minimum standards legislation that does not require generous adjustments for a wide range of people) as well as negative stereotypes and discriminatory attitudes. Psychologists and practitioners of critical health psychology can play a pivotal role in advancing the social model of disability and addressing the work that still needs to be done. Critical health psychology’s recognition of cultural identities and the need for humility, and the importance of research “with” not “on” people, are strengths of the discipline when working with people with disabilities.

A socio-ecological model of social inclusion (Riemer et al., 2020) demonstrates the importance of critical health psychology in exploring the psychosocial and psycho-emotional aspects of disability. Research methods that support the social model are methods that centre disabled people, affirm their aspirations, and support self-determination across the research process (Forshaw, 2007). There remains a need for research that considers the psychosocial nature of disabling and enabling cultures and is mindful of the epistemological positions at play (Goodley & Lawthom, 2005). A critical health psychology approach to disability is one that emphasises the importance of integrating and incorporating disabled people and families across all areas of research and practice.

Critical health psychology practitioners can advance disability related interests by:

- promoting awareness of the social model among healthcare professionals and the public.

- undertaking research with disabled people that utilises social models of disability and moves beyond identifying barriers to start to address barriers and change discourses around disability.

- developing policies that are by and for disabled people and families.

- engaging in therapy and practice that incorporates the social model into therapeutic settings and recognising the external factors affecting clients’ well being.

- recognise ableism and developing cultural humility (Atkins et al., 2023) as a way of recognising intersecting dimensions of disability, inequity, and privilege.

Critical disability studies

Critical disability studies (CDS) offers a theoretical and methodological basis for psychology practitioners. CDS challenges the limitations of various models of disability. Instead, CDS proposes the use of a “critical lens” to understand the lived experiences of individuals with a disability (Flynn, 2024). Key scholars in CDS frame the field in the following ways:

- disability is understood from the disabled person’s perspective (Reaume, 2014).

- social justice work for people with stigmatised bodies and minds (Minich, 2016).

- challenges approaches that pathologise physical, mental and sensory difference as being in need of correction (Reaume, 2014).

- a means to explore issues of illness, health, and disease that often intersect with race and class (Minich, 2016).

- an intersectional framework that looks to political perspectives such as feminism, Black, queer, and trans (Goodley et al., 2021).

To work effectively in CDS requires challenging our assumptions and attitudes around disability (Flynn, 2024). It also requires breaking down the boundaries between identity positions (e.g., race, gender, disability) to address the divide between disabled and non-disabled people (Goodley & Lawthom, 2005). As Shildrick (2012, p. 30) states, “Critical disability studies requires practitioners to consider the whole question of self and other.”

Two other models that emerged within critical disability studies are the affirmative non-tragedy model and Crip theory. The affirmative non-tragedy model is a theoretical framework within critical disability studies that challenges the traditional view of disability as a tragic condition (Flynn, 2024). Here are the main points:

- Positive Identity: The model emphasises that disability can have positive aspects and should be affirmed. It highlights the strengths and benefits of disabled lifestyles, promoting a positive social identity for disabled individuals.

- Cultural and Social Identity: It recognises the importance of disability culture and community, where disabled people can form their own social identities and communities.

- Opposition to Tragedy Model: The model stands in direct opposition to the dominant personal tragedy model of disability, which views disability as a negative and pitiable condition.

- Extension of Social Model: While it builds on the social model of disability, which separates disability from impairment and focuses on societal barriers, the affirmative model extends this by also affirming the positive aspects of disability.

Crip theory stems from queer theory and feminist disability studies. A central aspect of Crip theory is its critique of the binary structure of society according to which the able-bodied and the disabled are seen as opposites (Sandahl, 2003). Crip studies academics are staunch critics of the category of disability and say, “the problem with disability is not definitional but structural … Disability gets its power from specific cultural, geographical and historic contexts and these contexts pervade all ways of understanding disability” (Smilges, 2023, p. 10). This occurs irrespective of the model used. As Karlsson and Ryndstrom (2023) state, “Crip Theory provides a clear and powerful framework for undertaking a comprehensive critique of ableist inequalities in society and for developing activist strategies aiming to influence those who have the legislative power to address those inequalities” (p. 406).

Critical health psychologists can draw from all of the above models and theories in their practice. It is useful to consider which approach might be the most beneficial for the disabled people and families we are working alongside. In order to start to use and integrate theory into practice, it is important to understand ableism, a key driver of discrimination (Watson & Vehmas 2020). When a society is ableist, we prioritise the needs of non-disabled people and assume that the “normal” way to live is as a non-disabled person.

Ableism

Ableism is widely accepted within society and occurs across a range of everyday places and spaces. Ableism is defined as follows:

The act of prejudice or discrimination against people with disabilities and/or the devaluation of disability (Kattari, 2015, p. 375)

Institutional ableism refers to those systemic practices and processes that disadvantage and marginalise disabled people. Academic ableism refers to the way in which academia treats able-bodiedness and able-mindedness as the “norm” (see above) within academia and makes assumptions regarding social and communicative hyperability (Dolmage, 2017, p. 7). There are two main types of ableism: implicit (automatic and unconscious) and explicit (conscious and intentional). These can be broken down further into hostile (openly aggressive and discriminatory), benevolent (expressing pity or praise, being patronising or infantilising) and ambivalent (combination of both). Examples of hostile ableism include medical rationing during the COVID‑19 pandemic (see Brooks & Haller, 2024), workplace discrimination (e.g., pay inequity, lack of remote working options), or educational exclusion (e.g., lack of accommodations).

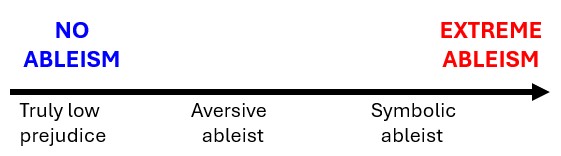

Friedman and Owen (2017) determined different types of ableism, discrimination, and prejudice, and how they intersect. They theorised two axes—symbolic and aversive. The logic behind both of these is that since there is human rights legislation, people’s disadvantages must be due to the person themselves, not discrimination. These terms can be summarised as follows and in Figure 3.4.2:

Symbolic ableism. This is high in explicit prejudice and high in implicit prejudice:

- expressed through symbols (e.g., opposition to affirmative action, ‘identity politics’). People rationalise and justify their prejudice.

- high in individualism and believes that people just need to try harder.

- regards people with disabilities as making excessive demands on the system and as demanding special favours.

Aversive ableism. This is low in explicit prejudice and high in implicit prejudice:

- being progressive and egalitarian is important to self-concepts. People believe that they are not prejudiced.

- act in prejudiced ways in ambiguous situations where it is harder to be “caught” or publicly shamed for being prejudiced.

Stereotypes, prejudice and discrimination are related but distinct concepts. Tran et al. (2024) define these concepts in relation to disability:

- Stereotypes: Common stereotypes for disability include perceiving an individual as personable and warm but also assuming they are incompetent or unhealthy.

- Stigma: Disability stigma—or the associations between disability as human difference and undesirable attributes—results in prejudice. Stigma for disability often is linked to whether the disability is visible or not.

- Prejudice: Among nondisabled people, prejudice may manifest as fear of contagion, pity for people with disabilities, or experiencing emotions of disgust when seeing someone with a visible difference.

- Discrimination: Discriminating against disabled people can include avoiding people with disabilities, deciding not to hire someone because of their disability status, or failing to provide reasonable accommodations.

Stereotypes, stigma, prejudice, and discrimination can show up as both macro-aggressions (systemic forms of discrimination and oppression that impact many disabled people) and micro-aggressions (intentional or unintentional, brief and often commonplace daily behavioural, verbal, and environmental indignities and interactions) (Jammaers & Fleischmann, 2025). For example, denial of disability experience, personal identity, privacy, or being patronised. Keller and Galgay’s (2010) research on micro-aggressions towards disabled people observed that micro–aggressions resulted in negative mental health outcomes. The participants felt perceived as helpless, experienced infantilising and/or patronising language, and were treated as second-class citizens. They were also either desexualised or considered exotic and offered unasked-for spiritual intervention. Jammaers and Fleischmann (2025) locate microaggressions within structural oppression of ableist society, highlighting how intertwined emotions, behaviours, and negative outcomes are.

Examples

The study of ableism in population health: a critical review (Mannor & Needham, 2024). This paper critically examines how ableism functions as a social determinant of health, advocating for a shift from the traditional medical model to a social model that recognises societal barriers as primary contributors to health disparities among disabled people.

Online culture perpetuates harmful stereotypes and misconceptions about disabled individuals through the use of ableist memes. Bree Hadley (2016) identified four commonly circulating categories of meme—the inspiration, the charity case, the cheat, and the comedic punchline (examples are shown in Table 3.4.1 and in Figure 3.4.5). Creating and sharing such memes contributes to ableist representations of disabled people. Also, depending on the images used in the meme (White person and middle/upper class with expensive equipment), privilege can be inadvertently mediate and diminish some of the impacts of some impairments.

Table 3.4.2 Ableist examples of memes

| Meme Type | Example | Why is it ableist? |

| The Inspiration | Images portraying individuals as overcoming their disability through working harder. Captions are meant to motivate able-bodied people by either shaming them for accomplishing less than disabled people, or by inspiring them with feats that the disabled subject performs (see Figure 3.4.3). | Objectifies disabled individuals for the benefit of non-disabled viewers; implies that disability is something to be overcome; ignores systemic and social barriers. Sets up exceptional examples as inspirational. |

|---|---|---|

| The Charity Case | Images portraying disabled individuals as objects of pity, often accompanied by captions soliciting sympathy or charity. Some images are “stolen” and repurposed or commodified for personal gain by non-disabled persons (Liddiard, 2014). | Reduces disabled people to their impairments; fosters a narrative that disabled people are helpless; upholds a medical view of disability as a sickness to be cured. |

| The Cheat | Images portraying people using disability equipment who are “not really disabled”. For example, a notebook for sale depicting a person in a wheelchair saying back in the day wheelchairs were for disabled people not fat people. | Promotes the misconception that individuals using mobility aids are exaggerating their disabilities or are simply lazy; undermines the legitimacy of invisible disabilities and personal experience. |

| The Comedic Punchline | Jokes that mock disabled individuals or use disability as a punchline. Memes that use offensive terms or depict disabled people in demeaning ways (Clark, 2003). | Perpetuate negative stereotypes; contributes to the marginalisation and dehumanisation of disabled people. |

Critical health psychology practitioners are in a unique position to challenge ableism by combining research, advocacy, and activism. All three can be used to address the systemic, social, and structural factors that create and maintain ableism through challenging stereotypes, stigma, prejudice, and discrimination. It is important to note that anti-ableist movements required on-going commitments to anti-racism and anti-capitalist agendas because “disability, race and class are categorically and phenomenologically entwined” (Smilges, 2023, p. 14). CDS offers a unique way of exploring health and illness experiences that considers the intersectional nature of a broad range of social drivers. Lived experience is also valued and appreciated.

Test your understanding of the core concepts so far with these five interactive questions.

Intersectionality in research and practice

My Story by Amber Rose

“So much of chronic illness is unexplored and stigmatized. I find that often as a chronically ill human being, I spend much of my appointments experiencing medical gaslighting, explaining illness to practitioners, advocating for myself, and fighting for appropriate medication. In fact, I would not have my disabilities if not for the medical neglect I dealt with as a teenager.

As a teenager, I suffered from an extremely heavy and painful menstrual cycle. I would bleed for months at a time, often passing out, dealing with chronic nausea and dizzy spells. I knew something was wrong, but every doctor that I went to told me that it was normal. That every girl when adjusting to their period experienced these symptoms, and for a while I believed them. It was only after bleeding for sixteen consecutive months, I finally went to the after-hours clinic in my hometown. This is where I was called not only hysterical, but drug-seeking and ‘just anxious’.

It was there, I also disclosed to a practitioner that I was queer, something that the nurse on duty felt was morally abhorrent. After receiving the verbal dressing down of my life, receiving no medications, and being told I just needed to ‘handle being a woman’, my fear of medical professionals was born. This mistrust would lead me to avoid health care to my own detriment, often putting off receiving help for minor ailments until they became an even larger and unavoidable issue.

My fear of having another experience like that led to me ignoring my glandular fever, until I developed chronic fatigue syndrome when I was sixteen. When I was twenty, I developed extreme nausea and was unable to keep solid food in my body for three months. I swallowed my fear and again went to the emergency room. This time, I was told that I could stand to lose weight and that I was exaggerating my symptoms. After fighting for blood tests, they found that I was extremely dehydrated and malnourished. I needed six IV bags, and intestinal feeding tube before I was released with ‘non-specified’ gastrointestinal issues.

What happened to me was never diagnosed and never properly treated. I still have symptoms today. This was the triggering event for my POTS (Postural Orthostatic Tachycardic Syndrome), a dynamic disability that affects both my mental and physical abilities. The level to which they affect me varies from day to day. If I had had medical intervention sooner, there is every chance I would not have this illness.

Chronic illness and disability are largely misunderstood by not only the medical community, but by the general population. From invasive questioning to feeling entitlement to my personal information and having to justify my disability to strangers, these are still regular occurrences in my life. At any given moment there is always someone willing to challenge me on my own abilities in life through their own narrowminded definition of disability. I have what is considered an invisible chronic illness, and as such I don’t fit into the stereotypical idea of what someone disabled ‘should’ look like. This is such a widespread issue that we must use symbols such as the sunflower lanyard as some sort of visual indication people are expecting of disabled populations to try and get the accommodations we need with as little fight as possible.

Ultimately, this has emphasised to me the importance of listening to disabled voices—not correcting, speaking over, or making assumptions. We deserve agency and autonomy within the system that was not built for us.”

What to read more?

Ableism Is a major barrier to mental healthcare (Wang et al, 2024). This research highlights how ableism within mental health services creates significant barriers for disabled individuals, leading to unmet needs and exacerbated health disparities.

Implications of internalised ableism for the health and wellbeing of disabled people (Jóhannsdóttir, et al., 2022). This article explores how internalized ableism affects the health and well-being of disabled individuals, leading to complex psychological, social, and physical consequences.

The history of clinical psychology and its relationship to ableism: Using the past to inform future directions in disability-affirming care (Bergstrom et al., 2024). This article reviews clinical psychology’s history and current relationship to ableism. The disability community reflects on current treatments and the impacts of disability stigma.

Critical health psychologist can challenge ableism by:

- engaging in a critique of overly medicalised approaches.

- centring disabled people and their lived experience.

- working alongside disability activists.

- addressing ableism in healthcare.

- applying an intersectional lens.

- advocating for supported decision making.

- and/or conducting critical policy analysis.

Contemporary approaches to disability in Aotearoa New Zealand

Aotearoa New Zealand’s contemporary approach to disability is rooted in a human rights framework that emphasises self-determination and inclusion. Key government directives include the following:

The New Zealand Disability Strategy: This strategy operationalises Aotearoa New Zealand’s commitment to the UNCRPD. It acts as a guide to government agencies. The strategy emphasises the removal of societal barriers and the promotion of inclusive practices across various sectors.

The Disability Action Plan: This presents priority work programmes and actions to deliver the eight outcomes in the Disability Strategy (Ministry of Health, 2025).

The Health of Disabled People Strategy: This strategy sets the long-term priorities for the health system, towards achieving equity in disabled people’s health, and wellbeing outcomes between 2023 and 2033. It provides a framework to guide health entities in improving health outcomes for disabled people and their whānau. Priorities include enhancing self-determination, ensuring accessible healthcare services, and integrating health systems to address broader determinants of health (Ministry of Heath, 2025).

The New Zealand government established Whaikaha – Ministry of Disabled People in 2022. The current focus of Whaikaha is to lead and coordinate strategic disability policy across government ministries. Another key approach to disability is Enabling Good Lives (EGL). This approach emphasises self-determination, flexibility, and inclusion for disabled people and their whānau (families). EGL represents a paradigm shift from the top-down, medical model of disability support to one that emphasises autonomy, inclusivity, and respect for disabled individuals as active participants in their communities. There are eight foundational principles (source: Enabling Good Lives) summarised in Figure 3.4.4 and outlined below.

- Self-determination: Disabled people are in control of their lives.

- Beginning early: Invest early in families and whānau to support them; to be aspirational for their disabled child; to build community and natural supports; and to support disabled children to become independent, rather than waiting for a crisis before support is available.

- Person-centred: Disabled people have supports that are tailored to their individual needs and goals, and that take a whole life approach rather than being split across programmes.

- Ordinary life outcomes: Disabled people are supported to live an everyday life in everyday places; and are regarded as citizens with opportunities for learning, employment, having a home and family, and social participation – like others at similar stages of life.

- Mainstream first: Disabled people are supported to access mainstream services before specialist disability services.

- Mana enhancing – The abilities and contributions of disabled people and their families and whānau are recognised and respected.

- Easy to use: Disabled people have supports that are simple to use and flexible.

- Relationship building: Supports building and strengthening relationships between disabled people, their whānau and community.

Disability prevalence in Aotearoa New Zealand

The Washington Short Set of survey questions is a set of questions developed for use in censuses and sample-based national surveys that are not disability specific (WG Short Set on Functioning (WG-SS) (The Washington Group on Disability Statistics, n.d.). They were included in Aotearoa New Zealand for the first time in the General Social Survey (GSS) for the 2016/17 collection year and have been consistently adopted in a wide range of surveys across government, including the Census. This has improved availability of data.

The 2023 Household Disability Survey provides a picture of disability in the Aotearoa New Zealand population, including disability prevalence and the outcomes and experiences of disabled people. The prevalence of disability is estimated at 17% (or 1 in 6 people) (Statistics NZ, 2025). Some key findings are:

- female disability rate was 18% compared to the male rate of 15%.

- child disability rate was 10% and disability rates increased with age (17% between 45-64, and 35% for people 65+years).

- the Māori disability rate was 24 percent, the Pacific people rate was 21 percent, and the Asian rate was 13 percent.

- the age-adjusted disability rate for the LGBTIQ+ population was 31 percent, significantly higher than the non-LGBTIQ+ rate of 17 percent.

- regions with disability rates significantly higher than the national rate were Northland (23 percent), Manawatū-Whanganui (21 percent), and Taranaki (21 percent).

- for adults, difficulties with physical functioning were the most common disabilities. For children, difficulties with mental health and with accepting change to their routine were the most common disabilities.

More detailed findings from this survey can be located at Statistics New Zealand.

Indigenous approaches to disability

As noted in Chapter 3.1, Indigenous psychologies are epistemologically and ontologically different in orientation to positivist psychological approaches. As a discipline, Critical Health Psychology has work to do in terms of affirming and supporting Indigenous ideas and approaches in health and related services.

Aotearoa New Zealand: Māori

The influx of colonial settlers from Britain to Aotearoa New Zealand also brought associated attitudes towards disability and health. Their imported ideas regarding disability, morality, and physical health starkly contrasted with belief systems and attitudes grounded within te ao Māori. The imposition of settler-oriented health systems resulted in significant disadvantage to Māori (Hickey, 2020). This continues today, with core institutions in the Aotearoa New Zealand health system designed by and for settler-colonials and their descendants (Reid et al., 2019). Models of health in practice remain dominated by biomedical approaches, which are grounded in positivist worldviews and reflect Western values (Reid et al., 2017).

Most Māori disabled identify as Māori first and may or may not identify as disabled, despite having some form of impairment (Hickey & Wilson, 2017). The term whaikaha is translated as “people who are determined to do well”. It is used in a disability context with tāngata (people) to refer to disabled people. The words tāngata whaikaha Māori is a strengths-based phrasing for Māori disabled. The phrase tāngata whaikaha Māori and whānau includes family members as an all-inclusive term that acknowledges the complexities of disability, ethnicity, and familial relationships.

The dominance of settler-colonial ideas means that tāngata whaikaha Māori commonly experience discrimination and face multiple systemic and structural barriers in accessing disability related services (King, 2019). This, alongside chronic underfunding of Māori health services, compounds the exclusion and isolation experienced by tāngata whaikaha Māori (King, 2019). In addition, social and economic factors such as lower income, poverty, higher unemployment, and reduced access to education combine to compound the poorer life outcomes experienced by tāngata whaikaha Māori (Statistics New Zealand, 2015).

Subsequent changes by successive governments have not addressed persistent inequities embedded into the health system, nor the prioritisation of Pākehā health needs (King, 2019). Māori continue to experience low-quality health services, which leads to poorer health outcomes (Graham & Masters-Awatere, 2020; Wepa & Wilson, 2019). These experiences are exacerbated for tāngata whaikaha Māori (Ingham et al., 2022). Effectively, the health and disability related needs of Māori are rendered less important and are at times unseen. This is particularly relevant in disability, where Māori identities are routinely overlooked by specialists and professionals (Hickey, 2020).

Some of the key health-related issues that tāngata whaikaha Māori in Aotearoa New Zealand continue to experience are poor quality care, culturally inappropriate care, and insufficient access to publicly funded specialist services (Graham et al., 2023; Graham & Masters-Awatere, 2020). Non-Māori-led research by non-disabled medical specialists has been entirely inadequate in addressing these issues due to extractive research practices that strip Māori of their cultural contexts (Seed-Pihama, 2019). Worse, medical publications continue to perpetuate deficit views of Māori and paternalistic assumptions regarding disabled persons (Graham et al., 2023).

Health and psychological research and practice in this area needs to enable self-determination and democratic participation by both Māori and disabled. There is some emerging material on this topic (for example, Ingham et al., 2021). However, there remains room for future research that engages iteratively with tāngata whaikaha Māori in the health and disability space.

Australia: Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders

Scott Avery (2018), in his beautifully presented tome Culture is Inclusion, brings the voices of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with disability to research and policy. There is no word for disability in Aboriginal languages. Rather, difference was accepted as part of the fabric of society and people included in everyday life. Avery explains:

First Peoples expression of humanity and diversity are more than just observances of functional linguistics. They speak of a belief system that values a person’s centeredness over biomedical and physical differences, and acceptance of difference as within the natural order of the world. It is a belief system that governs their behaviours, and comes with such a long-standing track record that it need not be consciously taught. Rather it is modelled through Indigenous people’s attitudes towards other members of their community (Avery, 2018, p. 5)

The cultural and belief systems of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are radically different to Western constructions of disability as a deficit that needs to be fixed, rehabilitated, or prevented (Berghs et al., 2016). In Australia, this dichotomy in belief systems has created a barrier to accessing disability services and supports, exacerbating inequities in health care.

Health-related research and practice that centres the perspectives of service providers and clinicians cannot, by definition, detect or determine the influence of bias regarding care provided to Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with disabilities (Avery, 2018). Instead, an ongoing intersectional approach that emphasises the perspectives of Indigenous groups and those with lived experience of disability must be taken. This may require considerations beyond the disability or impairment to include the wider context of people’s lives.

As Avery (2018, p. 158) notes:

The interpretation of what I ‘reasonable and necessary support’ in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities requires a much deeper interrogation. If people are starving, then food is necessary. If people are homeless, then shelter is necessary. These observations relate to the essential foundations of survival.

A key challenge is the way in which disability related supports (such as the National Disability Insurance Scheme or NDIS) end up being implemented. The default ends up being a transactional process, whereby eligibility is determined via a highly bureaucratic assessment process that centres biomedical need. Whilst well-intentioned, the NDIS positioning of people as passive participants, that the NDIS happens “to”, the narrow framings of need, and the unchanged nature of the power relationships wherein the assessor determines applicability of criteria falls short of the schemes intent to empower disabled people and provide choice and control. It is imperative to remain vigilant regarding implementation of programmes to avoid the slow return to default mechanisms and power structures.

Discussion questions

- What can be done to highlight power relationships in disability service provision?

- How can critical health psychology practitioners support disability service providers to improve their services and support Indigenous persons to access services?

Case studies and examples

The following section covers four case studies including a Māori community example, a policy case study, a case study of neurodiversity, and Rainbow health.

Case study: Kāpō Māori Aotearoa New Zealand

The community organisation: Kāpō Māori Aotearoa New Zealand Inc (KMA) is a national Indigenous organisation in Aotearoa. KMA was founded by blind, low vision, vision impaired and deafblind Māori and their whānau. Kāpō is the te reo Māori word for people who are blind, deafblind, or low vision. KMA is guided by Māori values, principles and practices to support tāngata Whaikaha (disabled people), and their whānau to attain whānau ora (well being) and to be strong self-advocates and leaders in their whānau and communities.

Pre-colonisation: Within the context of traditional Māori storytelling, or pūrākau, kāpō are depicted as strong and knowledgeable individuals. In these stories, blindness, disability, and even death are treated as ordinary parts of the rhythms of life. Disability and care are constructed as occurring within the context of wider familial and friendship connections, with an emphasis on the relationships that people have with each other. The stories of strong and knowledgeable ancestors who were blind (Tikao et al., 2009) provide a strengths-based alternative to the paternalism endemic to research on disabled persons.

The challenge today: Tāngata kāpō Māori, along with their whānau, have consistently reported facing challenges in accessing adequate and comprehensive health services. The existing provision of services is often characterised as patchy, difficult to access, and burdened by administrative complexities and bureaucratic barriers (Graham & Masters-Awatere, 2020). Moreover, the available data pertaining to the health service requirements of whānau kāpō Māori is deemed insufficient (Himona et al., 2019).

The research project: To address the above concerns, a research collaboration was developed. Professor Masters-Awatere, Dr Graham, and Ms Cowan worked to implement a research process that would identify key priorities for tāngata kāpō Māori and their whānau. Central to this collaboration was a clear commitment to self-determination for tāngata kāpō Māori, including intentionally centring tāngata kāpō Māori lifeworlds by documenting their experiences and those of their whānau. Self-determination over health data and related research (data sovereignty) means Māori determine (either alone or jointly) the type of data collected, the process of analyses, and the appropriate forms of reporting or dissemination (Cormack et al., 2019). The overarching objective was to advance the state of Māori and Indigenous peoples’ eye health and overall wellbeing.

Information was collected from a series of wānanga. Wānanga are distinct from Western-style meetings. Masters-Awatere et al., (2024) explain:

-[wānanga] meeting protocols support an understanding of the tapu (sacredness) of learning [21]. Protocols that may be unfamiliar to non-Indigenous researchers, but are familiar to many Māori, include (while not being restricted to) opening speeches and karakia (ritual prayers), ensuring appropriate time to engage in whakawhanaungatanga (relationship building), answering questions of attendees, and the provision of manaakitanga (hospitality). Intertwined with these are ways of engaging that are specific to Māori, which are location- and context-specific, such as regular use of te reo Māori (Māori language), humour, care for others, and deference to kaumātua (older persons) [22] (Masters-Awatere et al., 2024, p. 343)

The research team engaged in wānanga with tāngata kāpō Māori and their whānau over three years. They also engaged with key end-user informants and subject matter experts, and undertook a comprehensive literature review (Graham et al., 2023). The review collated previously published research and re-evaluated it from a Kaupapa Māori perspective. Taken together, the information collated across each of these data sets provided a comprehensive record of the experiences and preferences of tāngata kāpō Māori and their whānau.

Key outcome: The Kāpō Māori Declaration on Engagement and Exchange. A significant outcome of this research collaboration was the development of a core document, the Kāpō Māori Declaration on Engagement and Exchange. The Declaration aims to create a respectful and equal engagement between KMA, its representatives, and others. It provides a framework that clearly identifies the ways in which individuals, groups, organisations, agencies, and governing bodies can approach and engage with KMA and its representatives in a way that upholds the tino rangatiratanga (self-determination, sovereignty), kawanatanga (government), and oretitanga (equity) of tāngata kāpō.

Policy case study: Whānau Ora

The Whānau Ora initiative, based on Māori cultural values, was driven by the Māori parliamentary party as part of its coalition agreement with the National Party following the 2008 general election. Whānau Ora represents an alternative model in which the power of central government decision making is devolved to foster a greater sense of local community and individual responsibility. Embedded into parliament legislation and with funding secured, this initiative ensured that Māori centred values and practices were central to funding initiatives for Māori well being. It shifted thinking away from the narrowly defined biomedical practices of health into holistic alternatives.

The Whānau Ora Outcomes Framework built on the work of the Taskforce on Whānau Centred Initiatives, which carried out extensive consultation in 2009. It operationalised the ideals of Whānau Ora and provided a practical framework for assessing the outcomes of proposed projects. Whānau Ora is achieved when whānau are self-managing, living healthy lifestyles, participating fully in society, confidently participating in te ao Māori, economically secure and successfully involved in wealth creation, cohesive, resilient and nurturing, and responsible stewards of their natural and living environments. The framework recognises the long-term and progressive change required for whānau to achieve these aspirational goals by including short, medium and long-term outcomes (Whānau Ora). Whānau Ora signals a way forward for tāngata whaikaha Māori and tagata Pasifika with disability, and whānau. The Whānau Ora approach and Enabling Good Lives (EGL) are aligned with a mutual emphasis on building whānau capacity, collective leadership, and whānau planning.

One example of this in action is Te Pūtahitanga o Te Waipounamu, a Whānau Ora commissioning agency. Responsible for commissioning pieces of work that develop and enhance Whānau Ora, the organisation has seven pou (pillars) as their foundation (Te Pūtahitanga o Te Waipounamu). These seven pou provide the basis for assessing funding applications; projects must demonstrate their alignment to the Whānau Ora pou and how their project or kaupapa will benefit whānau. The seven pou are:

- Pou Tahi (one) aspires for whānau to be self-managing—exercising rangatiratanga on a daily basis and making informed decisions about their lives.

- Pou Rua (two) encourages whānau to lead healthy lifestyles, maintaining a quality of life that meets their health needs across all aspects of Te Whare Tapa Whā.

- Pou Toru (three) is about empowering whānau to participate fully in society and giving them the opportunity to participate in education and employment to their fullest potential.

- Pou Whā (four) portrays whānau as confidently participating in te ao Māori, secure in and proud of their cultural identity.

- Pou Rima (five) focuses on making sure that whānau are economically secure and successfully involved in wealth creation, building security for themselves and future generations.

- Pou Ono (six) is the goal that whānau will be cohesive, resilient, and nurturing, and that whānau relationships are positive, functional, and uplifting of all members.

- Pou Whitu (seven) encourages whānau to be responsible stewards of their living and natural environments, recognising our inherent and enduring connection (te ao tūroa) to the land and the benefits that come from strengthening that.

Taken together, the seven pou comprise a roadmap for Whānau Ora. When these seven pou stand tall and strong, they work together to uphold the wellbeing of individuals, families and communities.

Case study: neurodiversity, education and health

Neurodiversity is a biological reality and refers to the variation all humans have in neurocognitive functioning (Walker, 2025). We all think, learn, perceive the world, and process sensory information differently. This impacts how we engage in the world and how we interact with others. In this way we are all neurodiverse as no-one brain works the same. Education and health systems are typically set up for the majority, the normal, or neurotypical (their minds conform to constructions of normal in their society) (Hamilton & Petty, 2023).

Neurodiversity is different to being neurodivergent. An individual is considered neurodivergent if their mind functions differently from the dominant societal standards of normal. A group of people is neurodiverse if it includes more than one neurotype. As the concept of diversity applies to groups of people, an individual cannot be neurodiverse or have neurodiversity. Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD), Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD) and dyslexia are examples of neurodivergence (but there are others included in this umbrella) (Walker, 2025).

The neurodiversity paradigm is a specific perspective on neurodiversity and the Neurodiversity Movement is a social justice movement that seeks civil rights, equality, respect, and full societal inclusion for the neurodivergent (Walker, 2025). From the neurodiversity paradigm, neurocognitive difference is viewed as natural rather than defective, and is described in terms of neurotypes rather than disorders. Through acknowledging the role of socially constructed norms, we intentionally draw attention to the power dynamics involved. This includes aspects such as majority privilege that have contributed to framing of minority neurotypes as abnormal or deficient. While not all neurodivergent people subscribe to the neurodiversity paradigm, it is a useful tool for language and framing that avoids deficit narratives.

The illusion of inclusion – “The story it tells is nothing short of devastating.”

The Education Hub in 2024 gathered the stories from 2,400 neurodivergent young people, parents, whānau, teachers, educators, and support workers about their school experiences. The report highlights some of the wonderful work undertaken by individual educators and school communities. However, it also highlights systemic failure and broken systems. Ongoing systemic issues include inadequate funding, poorly set funding settings, a dearth of trained supports, unavailable and/or low-quality provision of services, unrealistically high teacher ratios in school classrooms, alienating school environments, and a desperate need for training and practice development across teaching staff. The report also highlighted how strong leadership, thoughtful policies, and cultures of inclusion all make a positive impact for neurodivergent learners.

For more information see the full report.

The story for tertiary settings is not much better. While all tertiary providers must now have a disability action plan, an increasing amount of research indicates that significant barriers for students and staff remain. Stigma, traumatising school experiences, and lack of universal design in tertiary environments mean that outcomes for neurodivergent and disabled learners remain poor (Hamilton & Petty, 2023).

What to read more?

Why critical psychology and the neurodiversity movement need each other (Thomas, 2024). This article challenges ableist trends within critical psychology and emphasises the importance of integrating neurodiversity perspectives to combat systemic marginalisation of neurodivergent individuals.

Lived experience voices

Personal stories and perspectives on how race, gender, class, and other identities intersect with disability can reveal the multiplicity of factors that disabled people experience. Critical health psychology has a long history of qualitative research that includes lived experiences. However, much of the time these stories remain in research spaces with minimal translation into practice that makes meaningful change, for the communities whose voices are highlighted. There are increasing movements in health and psychology more broadly that enable change as seen in the policy case study and Kāpō Māori Aotearoa New Zealand Inc (KMA) example in this chapter.

Mental distress is currently the leading cause of disability worldwide: the World Health Organization’s Comprehensive Action Plan 2013-2030 states a vision of a world where mental health is valued, promoted, and protected, where people experiencing mental distress can exercise the full range of human rights and access to quality care to promote recovery, and where lives are free from stigmatisation and discrimination (World Health Organization, 2021). The World Health Organization European Region’s (2024) Mosaic Toolkit is one recent response to that call and prioritises “collaboration led or co-led by people with lived experience, within and across health and other sectors” (p. v).

This same call can be seen from all marginalised communities “nothing about us without us”. It is essential that we involve people with lived/and or living experience. Disability affirming practice at the minimum includes representation of people with lived experience, creating communities to advocate and support each other, better training, and research that is done with and for the disabled community (Bergstrom et al., 2024). The case study below reveals the challenges but also highlights small changes that can be made.

Case study: Rainbow communities

Contributed by Amber Rose

Being disabled has plenty of challenges on its own, but when faced with the intersectionality of other minority groups people often get stuck in repeating cycles of disadvantage and injustice (Ker et al., 2022). Results from the 2023 Household Disability Survey note the significantly higher rate of disability in the LGBTIQ+ community: 31%, whereas the non-LGBTIQ+ rate is 17%. The question is why? Why should this statistical difference be so great, when Western centric culture insists it treats it patients and societies the same? The simple answer is equity instead of equality. A Rainbow person faces discrimination in many ways along the course of their life. This is both due to conscious and unconscious biases from the medical community, general community, and inner circles. The example of Jane illustrates intersectionality and the impact of social determinants of health.

Jane is applying for a job. However, the second her prospective workplace becomes aware that she is a part of the Rainbow community, she becomes less likely to be hired. Not only that, but if she had gotten the job, she was likely to be earning up to 10% less than her cisgendered, heteronormative counterparts. Due to these discriminatory practices, one in four Rainbow people are unemployed.

Unemployment almost always leads to poverty. Jane, after searching for months has run out of savings: she hasn’t been able to find a job and is now living in poverty. The odd, temporary jobs she has been able to find are barely covering rent, meals and utility, let alone covering any extra costs that come up, medical or otherwise. Poverty leads to decreased quality of life, both physically and mentally. It also decreases access to adequate housing, food and water, with costs being the primary barrier. As a result, people living in poverty, like Jane, are more likely to fall ill.

Not only is Jane more susceptible to illness as a result of her socioeconomic status, but poverty itself is a major discriminating component within healthcare. No expendable income means long waitlists, and often, an inability to pay even prescription and appointment costs within the public system. This economic lack of access to safe, equitable healthcare means minor health problems are pushed back, time and time again. Over time, these issues can turn into major health problems, and, without adequate care, full blown disabilities, often chronic illnesses or physical disabilities. Jane is now stuck in a repeating cycle that is entirely not of her own making. A cycle that thousands of Rainbow peoples fall victim to everyday.

The issues are not confined to the scenario outlined above. There are plenty of other Rainbow specific barriers, including but not limited to practitioner education, bedside manner and social acceptance. For example, members of the community often have to spend significant portions of, if not all of their appointment time educating practitioners on Rainbow-based healthcare. This involves explaining to their own doctors and psychologists the ins and outs of hormone replacement therapy, same gender sexual protection, and the practical information behind polyamorous relationships. In contrast, cisgendered and heteronormative counterparts can just go into an appointment with their identity in context, safely and with ease.

Additionally, a transgender person may experience other types of discrimination within a healthcare context. Misnaming and misgendering, accidental or not, being evangelised to, and other forms of emotionally and mentally taxing behaviours from practitioners all take their toll. A general lack of social acceptance can also cause anxiety and danger heading to and from appointments. The health system is already discriminatory towards Rainbow people and with the addition of systematic issues, these challenges will continue to worsen.

These Rainbow specific issues and disability specific issues are so much more than they appear on the surface; issues run deep. They have been around for a long time and may not be as glaring as other systemic issues have been. Rainbow spaces and communities have often been overlooked, and it is up to us and our new practitioners to have a more holistic, compassionate, and change-making view on healthcare and practice. Intersectionality in our healthcare spaces is becoming more and more of a necessity, and many times the education required from this must be self-directed. We must be committed to learning, compassion, and putting people at the centre of psychological practice.

Examples

There are many examples and reading you can do to expand your learning in this area. This is just a small sample from Aotearoa, New Zealand.

- Fraser, G., Brady, A., & Wilson, M. S. (2022). Mental health support experiences of Rainbow rangatahi youth in Aotearoa New Zealand: Results from a co-designed online survey. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand, 52(4), 472-489.

- Parker, G., Ker, A., Baddock, S., Kerekere, E., Veale, J., & Miller, S. (2023). “It’s total erasure”: Trans and nonbinary peoples’ experiences of cisnormativity within perinatal care services in Aotearoa New Zealand. Women’s Reproductive Health, 10(4), 591-607.

Counting Ourselves is an anonymous health survey designed by and for trans and non-binary people living in Aotearoa New Zealand (for more information https://countingourselves.nz/)

PRIDE stands for Program for Research on Identity, Development, & Emotional wellbeing (PRIDE) and is a psychology research lab based at Massey University

tps://www.pridelabnz.com

Critical health psychology practitioners can:

There are plenty of small, easy steps that can be taken towards helping the Rainbow community feel safe and accepted.

- adding preferred names to intake forms.

- staff wear name and pronoun pins regardless of being cisgendered or not.

- visible support in the form of pride information such as a Rainbow tick or information leaflet.

Small changes can mean the difference between a helpful, positive appointment, and an anxiety inducing, negative appointment. But these small, easy steps must be backed up with knowledge and seeking information about the community. Critical health psychology is a major part of that. By breaking down barriers using a significantly more diverse and accepting health model we can address patient issues holistically and without bias.

Areas of opportunity for critical health psychology

Greater understanding of disability can enable critical health psychology practitioners to respond to the groups with whom they work and the social problems they seek to ameliorate (McDonald et al., 2007). One way to do this is to develop shared narratives as a pathway through which marginalised individuals can contest and alter the frameworks of meanings that have underpinned and perpetuated their oppression (Madyaningrum, 2017).

Cross-fertilisation between disability studies and psychology gives each discipline insight, pools resources to support disabled people and empower action, and improves robustness and applicability of findings. The ability to learn from disability studies and disabled people can be achieved through respecting people’s individuality, being an inclusive practitioner, working harder to listen, and working harder for people to be heard (Richards, 2022). Holding a critical attitude to research is important, as is considering a diverse range of research methods (Forshaw, 2007).

There remains room to improve recognition of the power imbalances between disabled people and psychologists (Nelson et al., 2001). Psychologists need to recognise their responsibility to address disability-related discrimination and ableism (Teizaria et al., 2009). Solutions include engaging in practice within a commitment to recognising and exposing the impact of oppression and discrimination (Teizaria et al., 2009). There are many opportunities for allyship when coming from positions of humility.

Critical health psychology practitioners can offer reflection, partnership, and a critical examination of the processes and outcomes of the partnerships. Critical health psychology also offers practical ways to address power imbalances (through participatory research methods), alongside arguments that psychological well-being requires social and political transformation. Critical health psychology, with its orientation to systemic change, has the potential to advance with disability studies in partnership, endorsing disabled voices and striving for disability justice.

Research topics that require further exploration include:

- issues that the disability community is advocating for.

- disability diversity, intersectionality and social class.

- indigenous elements of disability.

- cultural narratives related to disability and class.

- awareness of personal responsibilities, biases, power and positionality.

- research and frameworks aligned with disability studies.

- collaboration between critical health psychology and critical disability studies.

- further development of the social model of disability.

Conclusion

We close this chapter coming back to question we posed at the start—“How can critical health psychology practitioners use disability theories and models in practice?”

“Making a start requires us to reflect on the history of disability in Aotearoa, New Zealand and more globally, including the difficult parts, such as the shameful embracing of eugenics. This chapter has introduced a broad-brush history of eugenics and disability, before discussing models of disability. These are an important base for understanding the context of psychology and disability. The section focusing on ableism frames how prejudice, stereotypes and discrimination work in the disability space, and how critical health psychology practitioners can actively address and reduce these in their practice.

Contemporary approaches to disability in Aotearoa New Zealand have been outlined, included current government strategies. Nonetheless, good policies and a United Nations convention signing does not necessary lead to positive outcomes. We have provided specific examples that we consider “good practice” grounded in the idea “nothing about us without us”.

Throughout our chapter we have provided specific challenges ranging from small personal goals to wider social change that you can take into your personal and professional lives. These ideas will be useful for all people working in psychology, health psychology, mental health and critical health psychology. To answer, “How can critical health psychologists use disability theories and models in practice”, we suggest “how can you not”?

References

Atkins, K. M., Bell, T., Roy-White, T., & Page, M. (2023). Recognizing ableism and practicing disability humility: Conceptualizing disability across the lifespan. Adultspan Journal, 22(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.33470/2161-0029.1151

Avery, S. (2018). Culture is inclusion: A narrative of Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people with disability. First Peoples Disability Network (Australia).