3.3. Defining health “problems” and shaping interventions: A critical health psychology perspective

Tracy Morison

Overview

This chapter offers a critical reflection on health psychology practice, focusing on how practitioners define health problems and intervene to support wellbeing at the individual, community, and population levels. Building on the frameworks introduced in Chapter 3.1—particularly ethics, reflexivity, and cultural safety—it explores the ideological, ethical, and political dimensions of professional practice. Drawing on the concept of complex reflexivity, I examine the often-unspoken values, assumptions, and theoretical frameworks that shape how practitioners decide when, how, and whom to help. Rather than assuming neutrality, the chapter invites a questioning stance: Whose knowledge is prioritised? Whose interests are served? What social conditions are left unchanged? Throughout, I emphasise that health psychology interventions are never value-free. They are shaped by broader social structures, institutional power, and professional worldviews. Case studies such as the SiRCHESI Project in Cambodia and the Sonagachi Project in India illustrate how different intervention approaches—grounded in different values and theories—can lead to different outcomes.

Key questions guiding the discussion include:

- Who defines what counts as a health issue?

- What exactly is considered the “problem”, and what needs to change?

- How do values, ethics, and theory shape intervention choices?

- How can reflexivity help avoid harm and promote justice?

Introduction

Health psychology is characterised by a dual focus on research and practice, “devoted to understanding psychological influences on how people stay healthy, why they become ill, and how they respond when they do get ill. Health psychologists both study such issues and promote interventions to help people stay well or get over illness” (Taylor, 1995, in Prilleltensky & Prilleltensky, 2003a, p. 200). My focus in this chapter is on professional practice: the role of health psychology practitioners in facilitating health and wellness—whether by keeping individuals well (proactive, health promotion) or by treating and managing illness (reactive, ameliorative). I conceptualise practice broadly as work in a range of settings (mental health, primary health, workplace, and community, among others), and typically falling into two domains: (1) clinical services and (2) health promotion. Practitioners in these domains intervene to help promote, maintain, or restore people’s health and wellbeing (Prilleltensky & Prilleltensky, 2003a). (These domains are discussed interchangeably in the chapter.)

The aim in this chapter is to examine what it means to be a “professional helper” (Prilleltensky & Prilleltensky, 2003, 2003b) involved in health interventions, and what counts as effective help. Thinking about how professional helpers go about deciding how to intervene in health-related issues is not just busy-work, or self-indulgent navel-gazing, however. Reflecting on this question brings to mind a much-loved book I had as a child, Harriet Help–a-lot (Watson, 1980), which captures what is at stake for helping professionals.

Harriet Help-a-lot: a cautionary tale

The gist of the story is that “Harriet is trying to help, but she is not always helpful.” Eager to help others Harriet often creates more problems than she solves. For instance, one hot summer’s day, she spots a carton of eggs on her neighbour’s doorstep. Her neighbour doesn’t appear to be home as her can isn’t in the driveway as usual. Harriet assumes the eggs must have been delivered while her neighbour was out and decides to help by moving the eggs to a shady spot on the driveway to stay cool and safe. Just after doing so, the neighbour reverses her car out of her garage and, splat, over the eggs! What Harriet hadn’t known is that the neighbour was on her way out. She’d parked in the garage for the car to stay cool and left the eggs for collection.

The neighbour shouts angrily at Harriet, asking why she hadn’t asked whether help was needed or what she could do. By the end of the story, all her neighbours are cross with well-meaning Harriet, who then has a difficult lesson to learn about helping.

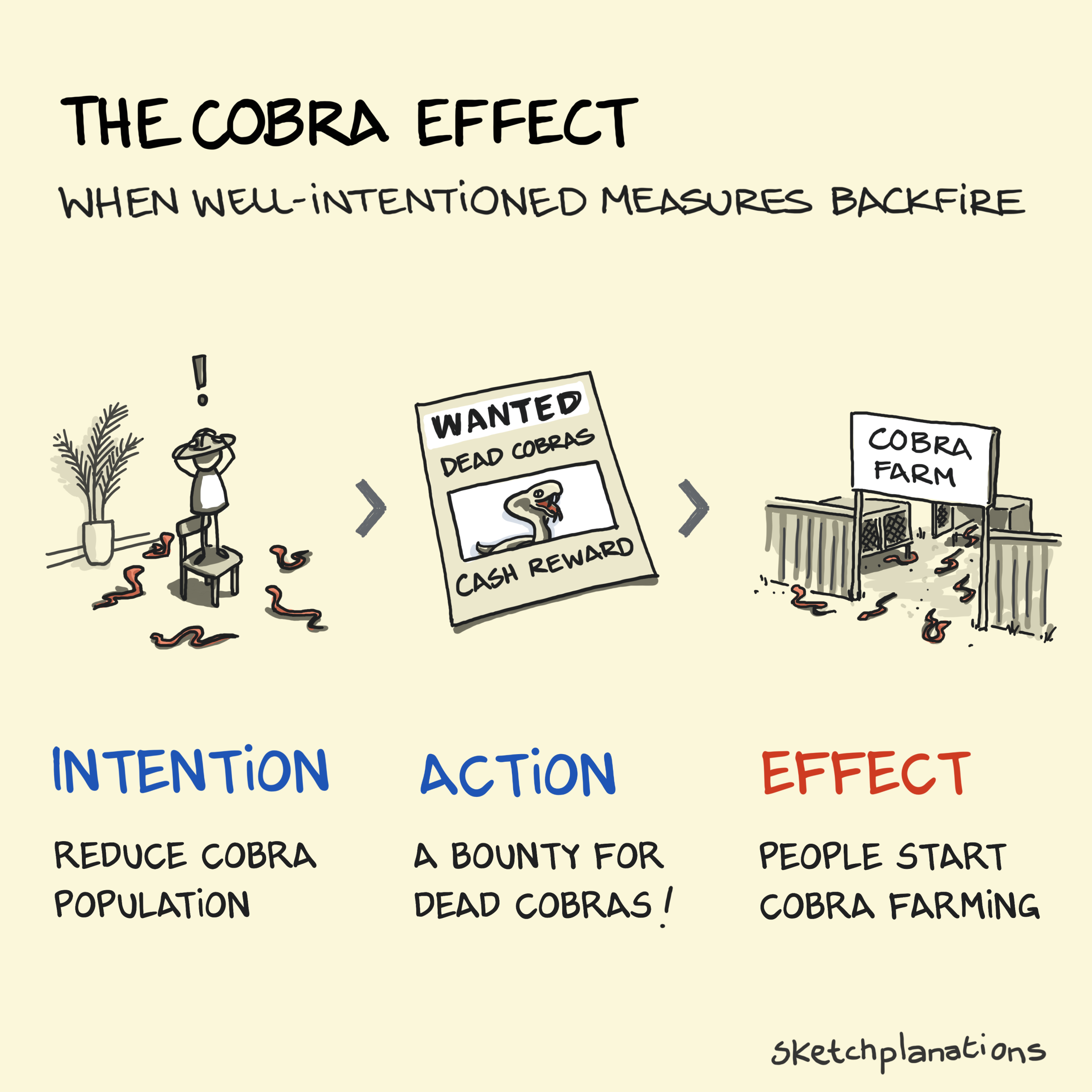

This little story about poor Harriet-help-a-lot illustrates the pitfalls of well-intentioned but misguided assistance and the importance of communication and seeking information to being able to help effectively. It serves as a cautionary tale for professional helpers, no matter how well-intentioned, about the complexities of intervention. Deciding when and how to intervene requires careful consideration, as uninformed or poorly planned actions can leave those we aim to help worse off. Without a clear understanding of the problem and its underlying causes, interventions risk leading to unintended consequences or, at worst, exacerbating the very issue they seek to address. This phenomenon is sometimes called the “cobra effect”, as explained in Textbox 1.

Textbox 1. The Cobra Effect

The term cobra effect describes a situation where an attempt to solve a problem results in unintended and counterproductive consequences, ultimately worsening the issue. The term originates from a policy implemented by the British colonial government in India, which offered a bounty for dead cobras to reduce their population. In response, people began breeding cobras to collect the bounty, inadvertently increasing the snake population rather than reducing it. The cobra effect, therefore, refers to interventions that produce an unintended outcome opposite to what was intended (Bartholomae & Stumpfegger, 2021).

A recent health-related example of this is discussed by Davis (2020) in her podcast episode Unintended Consequences, which examines the impact of a government intervention banning tobacco and alcohol sales during South Africa’s COVID-19 lockdown. While the ban on alcohol was intended to reduce pressure on hospital trauma units by curbing alcohol-related injuries, the inclusion of tobacco—due to other government priorities—had unforeseen consequences. The prohibition fuelled the illegal tobacco trade, leading to “massive criminal syndicates… enjoying the payday of their lives” (Davis, 2020) as tobacco sales were driven underground.

As Davis’s (2020) example illustrates, the cobra effect highlights the risks of imposing interventions from a detached, top-down perspective. When those in power set the agenda without consulting relevant stakeholders, well-meaning policies can lead to significant and even more severe unintended consequences.

Critical health psychology requires practitioners (as well as researchers and educators) to actively reflect on how we collectively define outcomes for others (Prilleltensky, 2003a). Those who seek to help others are part of the same social world they aim to transform. Their biases, values, and worldviews are shaped by the context in which they live and work (Horrocks & Johnson, 2014). Consequently, all decisions about “helping” inherently involve ideological choices. What is problematic is not the presence of ideology, but the failure to make the underlying values, assumptions, and guiding frameworks—or theories—explicit (Raphael, 2000). This makes complex reflexivity essential to ethical and effective practice.

In this chapter, I focus on intervention as a core element of professional practice, exploring:

- how health psychology practitioners decide when, how, and whom to help;

- the role of values, ethics, and theory in shaping health problem definitions;

- the concept of complex reflexivity as a tool for avoiding harm and promoting justice;

- how theoretical framing influences intervention strategies and outcomes.

By critically analysing how health problems are selected and framed, this chapter highlights the importance of contextual, ethical, and participatory approaches to intervention that centre wellbeing and liberation. In the next section, we take a step back to consider the “why” of critical health psychology practice: what it means to take a critical approach to practice, and how overarching values, ethical commitments, and theoretical assumptions shape how we work in the world.

Learning objectives

After completing this chapter, readers will be able to:

-

Explain how health psychology practitioners’ assumptions and values shape choices about what and whom to target in interventions.

- Critically discuss the potential for unintended consequences that might arise as a result of an intervention.

- Identify and reflect on the ethical, moral, and political implications of intervention.

- Explain the importance and implications of reflexive use of theory in planning interventions.

- Apply key concepts from critical health psychology—such as power, cultural safety, and complex reflexivity—to evaluate real-world examples of intervention.

Why do we help? Taking a critical approach to health psychology practice

Critical health psychology requires practitioners (as well as researchers and educators) to actively reflect on how we collectively define outcomes for others (Prilleltensky & Prilleltensky, 2003a; Raphael, 2000). Interventions, by definition, are purposeful attempts to change individuals or groups. As Guttman (2000, p. 27) notes, they inherently involve conflicting values and ethical dilemmas, some of which may be subtle or hidden. Yet mainstream psychology—and by extension, health psychology—has often denied these ideological and political dimensions, instead claiming scientific neutrality (Prilleltensky & Prilleltensky, 2003a; Raphael, 2000).

Critical health psychology, in contrast, insists on what I term “complex reflexivity”, drawing on Parker (1994) and Bolam and Chamberlain (2003). This goes beyond reflecting on personal biases, training, or cultural positioning—what we might call “light” reflexivity, as discussed in Chapter 3.1. Complex reflexivity invites us to see ourselves not only as clinicians or researchers, but as socially embedded actors whose work has moral and political consequences (Fox, Prilleltensky & Austin, 2008).

In this sense, critical health psychology forms part of a broader critical psychology project that “starts from fundamental concerns with oppression, exploitation and human well-being” (Hepburn, 2003, p. 2). Textbox 2 provides an overview of key principles that guide this approach. Importantly, the term “critical” here does not mean being negative or fault-finding but rather denotes an analytical and questioning stance—one that examines not just what we do, but why and how we do it. This includes turning the analytical gaze inward: to psychology’s own assumptions, methods, ideologies, and social functions (Parker, 2015).

Textbox 2. Key features of critical psychology (Parker, 2015)

Critical psychology offers alternative ways of understanding and practising psychology that are socially aware, politically engaged, and ethically grounded. It encourages us to rethink what psychology is, what it does, and whose interests it serves. According to Parker (2015), key features of critical psychology include:

-

Working alongside people, not just observing them

Instead of separating the psychologist from their “subjects”, critical psychology emphasises working with people. It encourages psychologists to turn the gaze back on themselves and their own roles, asking: How are we part of the systems we study? -

Situating individuals in their social and political context

Critical psychology highlights how people’s experiences are shaped by wider social, cultural, historical, and economic forces. It rejects reductionist approaches that focus solely on the individual. -

Valuing diverse methods and perspectives

Critical psychology embraces transdisciplinary approaches and methodological pluralism. It draws on insights from sociology, anthropology, philosophy, political science, and beyond to understand complex human issues, rather than relying on a narrow set of methods. -

Recognising that knowledge is interpretive

Critical psychologists understand that knowledge is always constructed—not simply a mirror of reality. This means being attuned to the meanings people make, and how those meanings are shaped by power. -

Practising reflexivity, not claiming objectivity

Critical psychology values reflexivity—the ongoing process of reflecting on how our positions, values, and assumptions shape our work, instead of pretending to be neutral or objective.

Together, these principles support a psychology that is committed to justice, transformation, and human dignity, rather than simply adjustment or control.

Within this broader project, critical health psychology offers a distinctive perspective—one that (1) foregrounds the social embeddedness of health and illness, and (2) highlights power and privilege in shaping health outcomes and care (as discussed throughout this book). Its two central goals are wellbeing and liberation (Prilleltensky & Prilleltensky, 2003b). Critical health psychologists therefore aim to contribute to both emancipation and quality of life (Prilleltensky & Prilleltensky, 2003b). A key premise is that people cannot be truly well unless they are also free from the systems and structures that constrain or harm them. Wellbeing and liberation, in other words, are inextricably linked (Prilleltensky & Nelson, 2017).

From a critical health psychology standpoint, wellbeing is not limited to the absence of illness or individual mental health. It includes physical, emotional, relational, cultural, and community wellbeing, and emphasises the conditions that support human flourishing, dignity, and connection. This means taking seriously the social, economic, and political determinants of health, and recognising the role psychology can play in either supporting or undermining those conditions. Mainstream psychology has been criticised for adopting a narrow view of its ethical responsibilities, often focusing on individual adjustment or minor reform rather than structural change (Fox et al., 2008).

The goal of liberation, meanwhile, calls us to address not just the experience of illness or distress, but also the underlying determinants and systems that produce inequality. This demands critical attention to power relations—within therapeutic encounters, health institutions, and the discipline of psychology itself (Bolam & Chamberlain, 2003). Practitioners are therefore encouraged to question the assumptions underpinning their work:

- whose knowledge is prioritised?

- how are professional practices shaped by—and shaping—broader social structures?

- whose interests are being served?

Dominant definitions of health are typically set by those with the most societal power. In many cases, policymakers and professionals define health problems and solutions, while the voices of service users—particularly those from marginalised communities, such as Indigenous people, are silenced or ignored (Ratima, et al., 2015; Reid, et al., 2019).

Psychology’s dominant values and claims to scientific objectivity have also been shown to align with and reproduce social inequalities (Fox et al., 2008; Burman, 2003; Parker, 2015). Feminist and Indigenous scholars have long pointed out that practitioners from minoritised groups—women, gender-diverse people, Indigenous professionals, and people of colour—are often devalued, sidelined, or excluded (Burman, 2003; Came, 2014; Prilleltensky, et al., 1999).

Institutional hierarchies typically privilege the perspectives of dominant social groups, embedding inequity into psychological systems and practices. As Came (2014) argues, racism remains present in health systems and professional spaces, including psychology. This means that psychology, as a powerful institution, can itself cause harm, particularly for those who are already socially disadvantaged (Fox et al., 2008; Prilleltensky & Nelson, 2017).

These dynamics are also visible in the ways problems and solutions are defined. Health interventions often focus on getting individuals, especially those from lower-income groups, to change their behaviour, rather than addressing the structural conditions that produce ill-health in the first place (Mik-Meyer, 2014). (This relates to the social gradient in health; Marmot, 1994, 2002, 2003[1]).

In closing this section, let me return to the idea of wellbeing and liberation as interconnected goals, and show how this lens might reshape intervention.

Imagine a psychologist working with a client who experiences distress about her body and eating habits. A conventional approach might focus on building self-esteem, teaching cognitive-behavioural strategies to challenge negative thoughts, or offering nutritional guidance. These may be helpful—but a critical psychologist would also ask: What cultural messages about beauty, weight, and morality are shaping this experience? How do gendered, racialised, or classed norms contribute to body shame? And what role does the healthcare system itself play in reinforcing fatphobic or exclusionary assumptions?

Even the setting of care matters. Is this client at a private clinic with mostly affluent patients, or a public service where resources are limited and people may feel stigmatised? When disordered eating is treated purely as an individual issue, interventions often focus on teaching people to “cope” or adapt—rather than challenging the conditions that make distress so common in the first place.

This is not to say therapy is not valuable; but a liberation-focused approach invites broader questions—about power, cultural norms, and social transformation. It creates space for interventions that support individuals and push back against the systems that cause harm.

This example highlights a central theme in this chapter: that effective, ethical practice in critical health psychology requires careful reflection on the level at which we intervene and the scope of what we aim to change. Interventions can target individuals, relationships, communities, or broader social systems, and they can range from reactive responses to proactive efforts to promote long-term wellbeing and justice.

Table 3.3.1 (below) offers a way to make these ideas concrete and an overview of what is to come. It brings together two key dimensions: timing and scope of intervention (e.g., is the goal prevention or management?) and ecological level (e.g., individual, relational, or collective). This table also reflects three sets of values identified by Prilleltensky and Nelson (2017) as central to critical health psychology practice, and which can be used to help guide ethical decision-making in critical health psychology practice, ensuring that interventions are aligned with the goals of wellbeing and liberation at personal, relational, and collective levels. As I discuss in the next section, all interventions are shaped by underlying values and assumptions about what counts as a problem, who is responsible for addressing it, and what kinds of outcomes are prioritised.

Table 3.3.1. Timing and Level/Scope of Intervention from a Critical Health Psychology perspective with practice examples

|

TIMING & LEVEL / SCOPE OF INTERVENTION

|

🟩 PRIMARY INTERVENTION

Health promotion / preventing onset of health issue Proactive (universal) ➡️ prevent adverse health outcomes ➡️ pre-empt: risk factor reduction for entire population, usually via large social changes & public policy |

🟧SECONDARY INTERVENTION

Early detection & response Proactive (high risk) ➡️ early detection to diagnose conditions & prompt treatment ➡️ slowing progression & minimising impact |

🟥 TERTIARY INTERVENTION

Managing long-term conditions & improving quality of life Reactive (indicated) ➡️ lessen negative impact of health condition & prevent complications |

| MICRO LEVEL – Individual / intra-personal

Values for Personal Wellbeing:

|

|

|

|

| MESO LEVEL – Interpersonal / relational

Values for Relational Wellbeing

|

|

|

|

| MACRO LEVEL – Collective

Values for Collective Wellbeing

|

|

|

|

The above table serves as a touchpoint for the remainder of the chapter as we explore how health issues are defined and addressed in practice.

What is the problem, and what should be done about it? Defining health issues

Determining what exactly needs to change is a fundamental aspect of intervention design, yet it is often overlooked. This is a crucial issue because “different problem interpretations lead to different kinds of solutions” (Fox et al., 2008, p. 7). When this issue of problem definition in health psychology is critically examined, several key questions emerge:

- what is considered a health issue, and why? / Why is it framed as a problem?

- who determines what is ‘good’ or ‘bad’ for health, and on what basis?

- who or what should be the target of an intervention, and why?

- what is the desired outcome?

These seemingly straightforward and often taken-for-granted questions are crucial in shaping how interventions are framed, designed, and implemented. How a problem is defined directly influences who is targeted, the strategies used, and the anticipated outcomes (Stephens, 2008). If these questions are not carefully considered, interventions may not only fail to achieve their intended goals but could even exacerbate the issue, or create new unintended consequences, as seen in the examples of the cobra effect. Thus, Prilleltensky and Nelson (2002, p. 27) maintain that “each time psychologists define problems, assign roles to themselves and their clients, and determine an intervention, they are enacting values with multiple consequences. Problem definition is not just a professional act but a political one as well.”

In this section, I discuss how decisions about intervening are shaped by a variety of social and contextual factors—such as the type of evidence collected (e.g., statistical data or personal testimonies), national priorities (budgets and policies), pressing local issues, and, importantly, the assumptions, values, and ethics of decision-makers (Stephens, 2008). Making determinations about how to intervene is therefore not always straightforward, because, as Seedhouse (2005, p. xix) argues, these determinations are “based on a point of view about the ways people should and should not behave, and ultimately therefore on some notion of the good society. And since the good society can be thought of in very different ways, and since health promoters inevitably hold a wide range of political philosophies, health promotion is riddled with deep theoretical tensions.” This point is illustrated by Seedhouse’s (2005, pp. 68–69) (tongue-in-cheek) example of two “morally controversial health promotion plans” related to smoking, shown in Textbox 3.

Textbox 3: Morally controversial health promotion plans

Plan A: HEALTH PROMOTERS SHOULD ENCOURAGE PEOPLE TO SMOKE

RATIONALE

- Coping: Smoking can help people deal with stress.

- Economic Benefits: (a) boost job opportunities in tobacco industry, potentially reduces unemployment-related health issues; (b) increased cigarette sales raise tax revenue, which governments could spend on health

- Population Impact: Smokers tend to have shorter lifespans, and encouraging smoking might lower the number of elderly people with chronic illnesses, potentially reducing state spending on geriatric care

- Social Belonging: Many young people see smoking as “cool,” which helps them feel a sense of belonging—a factor that is important for overall well-being.

- Enjoyment: Most smokers report that smoking is pleasurable

METHODS TO PROMOTE SMOKING

- Advertising Freedom: Advocate for unrestricted advertising of cigarettes, arguing that any legal product should be freely promoted in a capitalist market.

- Enjoyment Guidelines: Provide comprehensive, research-based advice on how to get the most enjoyment from smoking—such as tips on choosing the right cigarette, using filters appropriately, and determining optimal smoking frequency.

- Highlighting Benefits: Publicise the mental and social benefits of smoking.

Plan B: HEALTH PROMOTERS SHOULD TRY TO STOP PEOPLE FROM SMOKING

RATIONALE

- Health Impact: Smoking causes illness, shortens lives, and reduces physical fitness.

- Economic Costs: Treatment for smoking-related diseases is expensive, often straining public funds, and contributes to absenteeism and reduced productivity.

- Wider Harm: Smoking harms non-smokers through passive exposure and imposes additional economic costs on taxpayers.

- Aesthetic and Hygiene Concerns: Smoking is considered unattractive (it stains) and unhygienic (unpleasant odour).

METHODS TO PROMOTE SMOKING CESSATION

- Education: Provide clear, comprehensive evidence about the harms of smoking so that individuals can make informed decisions.

- Training: Offer accessible and widespread stop-smoking programs and techniques wherever people smoke, ensuring ample opportunities for behaviour change.

- Indoctrination: Distribute anti-smoking propaganda to counteract tobacco marketing, using powerful imagery and messages that emphasise the severe health risks and ethical issues associated with the tobacco industry.

- Legislation: Implement policies such as banning tobacco advertising, imposing high taxes on tobacco products, restricting smoking in public places, and requiring smokers to cover the costs of their smoking-related medical treatments.

- Prohibition: In extreme cases, consider the outright banning of smoking to protect public health and refuse government subsidy for smoking-related healthcare.

Seedhouse notes that while Plan A may seem clearly problematic—possibly even shocking—and Plan B might appear to need less ethical justification at first glance, both plans arise from different interpretations of smoking’s benefits. Hence, both approaches to smoking can be thought of as morally controversial, even if one appears less problematic because it conforms to our widely accepted belief that smoking cessation is inherently “good”. While this may seem self-evident, Seedhouse (2005) reminds us of the importance of distinguishing between objective facts and the value judgments that underpin them. Neither plan is a value-neutral response to the evidence; instead, each is built from a mix of empirical data and value-driven opinions, resulting in a specific health promotion strategy. Seedhouse (2005, p. 68) depicts this as:

Various pieces of EVIDENCE + various sorts of OPINION [based on values] = health promotion PLAN.

The example of these two plans, shows how different political, professional, and cultural standpoints about what is considered “good” or “bad”—and hence what the ideal outcomes should be—generate vastly different approaches to the same issue. In line with these differing sets of values and assumptions, different kinds of evidence are seen as valuable, and interpreted and used to support different approaches and envisaged ideal outcomes. Thus, defining what constitutes a health problem is never a neutral or purely technical process. It is always shaped by human values and assumptions, even intervening in health issues that one might take for granted as obviously harmful or “bad”, and for which there might be a wealth of evidence, as in the case of smoking (Dawson & Grill, 2012; Signal, et al., 2015). Ultimately, “what constitutes a health problem is largely in the eye of the beholder” (Mik-Meyer, 2014, p. 32).

For our purposes of reflecting on health psychology practice, we might then say: EVIDENCE + OPINION [values and assumptions] = PROBLEM DEFINITION and INTERVENTION APPROACH. I discuss each of these aspects (evidence; values and assumptions) separately below, but by the end of the discussion it should become apparent how interrelated they are.

Evidence-informed practice (and its limitations)

Understanding the causes of health and disease is essential for effective intervention. Evidence is crucial as it provides justification for specific approaches to interventions—the ways they are planned and designed to be applied by professionals. Evidence of a health issue can help identify its relevant causes, determine whether to intervene, design interventions, and evaluate outcomes. (Carter et al., 2011; Raphael, 2000). Evidence-based practice is therefore often championed. The challenge, however, is that evidence signals that something should be done, but not necessarily what to do or how to do it (Carter et al., 2011). As Carter et al. (2011, p. 456) point out:

“Evidence-informed practice is never straightforward … not least because it is social and political, involving contests between community, corporate, bureaucratic, and political stakeholders.”

Firstly, what counts as valid evidence might be disputed. For example, some health promoters see quantitative evidence like epidemiological data as more objective and reliable than qualitative data like patient narratives or community needs assessments (Stephens, 2008). Secondly, the determinants of a health issue may be debated. There are frequent disputes over which factors contribute to health outcomes, whether a particular factor plays a role at all, and how significant it is compared to others. These disputes are often related to the value people place on certain factors, and the implications of identifying them as risk factors, particularly in terms of what actions should be taken in response. Finally, regardless of the evidence that is ultimately used, it requires interpretation, inevitably bringing values and worldviews into play. These all influence which causal factors are considered in the design, execution, and evaluation of interventions (Hickson, 2015; Raphael, 2000).

The role of values and assumptions in defining health problems

Defining what constitutes a health problem is never a neutral or purely technical process—it is always shaped by human values. Although health work—like disease prevention or rehabilitation—may seem inherently moral or “good”, closer reflection reveals that every aspect of it is ultimately driven by value judgments (Seedhouse, 2008). As Carter et al. (2011) note, values underlie all health interventions. The example of the morally controversial plans above prompts us to ask: What values underlie each plan, and how should health psychologists decide between them?

Values are principles that guide behaviour, and so guide decisions about which issues are labelled as “problems”, who or what becomes the focus of intervention, and what outcomes are prioritised (Prilleltensky & Nelson, 2017). In this sense, values are not just personal preferences about what matters, but broader ideological commitments—beliefs about how society should function, what is desirable, and what constitutes a “good life”. In Western contexts, for instance, a “healthy weight” is often framed through a biomedical lens that emphasises individual responsibility, discipline, and self-control. As Mik-Meyer (2014, p. 31) argues, this framing “praises certain physical measurements of the body, as well as dominant societal values such as self-responsibility and self-control”. It can lead to moralising portrayals of those considered overweight as lazy or psychologically troubled, or even bad parents or partners according to research in this area (Warbrick et al., 2018). Yet these portrayals reflect only one value system. Other cultural or political traditions may define health—and desirable bodies—differently.

Alongside values, interventions are also shaped by assumptions—people’s (often unspoken) beliefs about how the world works. These include assumptions about human nature (e.g., whether people are rational decision-makers), about causality (e.g., whether health outcomes are due to individual choices or structural forces), and about professional roles (e.g., whether practitioners are experts or facilitators) (Prilleltensky & Nelson, 2017). Such assumptions influence how health problems are framed, the kinds of explanations that are prioritised, and which solutions are considered viable (Stephens, 2008). For example, assumptions about personal agency often underlie behaviour-change models, whereas assumptions about structural inequality might inform approaches focused on social determinants of health. Some assumptions can appear “natural” or “commonsense”, but all are historically and culturally situated. When unexamined, they can lead to interventions that reinforce dominant ideologies, exclude alternative ways of knowing, or inadvertently marginalise those they intend to help (Metzl & Hansen, 2014; Prilleltensky & Prilleltensky, 2006; Prilleltensky & Nelson, 2017).

How should we help?

Once a health issue has been defined, decisions must be made about what kinds of interventions are appropriate, ethical, and effective. This section explores three interrelated aspects that shape intervention practice in critical health psychology:

- values and assumptions shaping professional responses to health issues;

- ethical principles guiding decision-making; and

- theoretical frameworks informing how problems and solutions are conceptualised.

Together, these elements play a role in how practitioners engage with individuals and communities, and how they strive to promote wellbeing and social justice in real-world contexts.

Values and assumptions shape modes of practice

Values and assumptions are intertwined and produce distinct modes of practice—that is, characteristic ways of understanding problems and intervening in people’s lives (Prilleltensky & Nelson, 2017). Together, they shape what is seen as problematic, what kinds of change are considered appropriate, and who is responsible for achieving it. The interplay between values and assumptions is helps explain why different practitioners interpret and address the same issue in markedly different ways. Consider the contested issue of “teenage pregnancy”[2], for instance. It is more than a health concern; it is a morally charged topic with multiple, often conflicting framings, each reflecting different assumptions and values and, in turn, different responses to the issue (Macleod, 2014; Pihama, 2011), as summarised in Table 3.3.2.

Table 3.3.2. Framing “Teenage Pregnancy” – Values, Assumptions, and Intervention Approaches

| Framing | Assumptions | Values | Intervention Approaches |

| Individual problem

➡️focus on personal responsibility and behaviour |

|

|

|

| Gendered social issue

➡️emphasis on power, inequality, and structural factors |

|

|

|

Likewise, in clinical work, for example, practitioners working with people living with type 2 diabetes, may focus on behaviour change—such as increasing exercise or improving diet. While this is often helpful, framing the issue primarily in terms of individual choices or motivation can obscure the broader social, emotional, and economic contexts shaping those behaviours, including factors like food insecurity, the emotional toll of stigma, caregiving responsibilities, and limited access to affordable healthcare. A more holistic approach might involve working collaboratively with clients (and, where appropriate, their whānau) to explore how these wider factors influence their health, and to co-develop strategies that acknowledge both personal agency and structural constraints. This broader framing also invites psychologists to advocate for culturally responsive care and more accessible services, as argued by scholars calling for greater attention to structural and contextual factors in clinical work (Metzl & Hansen, 2014; Prilleltensky & Prilleltensky, 2006; Prilleltensky & Nelson, 2017).

Whether in health promotion or clinical practice, the values embedded in interventions influence not only how support is provided, but what kinds of behaviours, choices, and ways of living are encouraged or discouraged. As Mik-Meyer (2014, p. 31) notes, “health psychology interventions often implicitly prescribe how people ought to live, based on their ideas of what is good, correct, or worthwhile”. By this point in the discussion, it may become apparent that values and ethics are deeply connected. To illuminate this further, let me return to the earlier example of smoking. Since smoking is known to harm health, it is commonly accepted that it should be discouraged or restricted in certain contexts, and that working toward reducing smoking rates is inherently ethical (Seedhouse, 2004). Ethical considerations involve determining what actions best ensure human wellbeing—judgments about what is good or valuable (Carter et al., 2011). Thus, it is crucial to reflect on the ethical dimensions of intervening in people’s lives, both for moral reasons and for the practical effectiveness of interventions (Guttman, 2017), as discussed in the following section. This is another aspect of the question about the “how” of health psychology intervention.

Ethics and decision-making in health psychology practice

While values and assumptions shape how practitioners understand and approach health issues, ethical considerations come to the fore when deciding how to intervene. Guttman (2017) highlights key ethical concerns in health interventions, including the potential infringement on privacy, autonomy, and equity. Some interventions may unintentionally widen social disparities, benefitting those who are already better off while further disadvantaging marginalised groups (Reid, 2015). Additionally, interventions can have unintended psychological and social consequences, such as reinforcing stigma or labelling individuals in harmful ways (Lupton, 2015; Warbrick et al., 2018). They may also shape cultural norms by idealising certain lifestyles (such as being thin, fit, or self-disciplined), and by promoting the idea that being healthy is a moral obligation. This can create pressure to conform and exclude or judge people who do not or cannot meet these ideals (McPhail-Bell et al., 2015). In doing so, such interventions raise questions about whether people are genuinely able to make free and informed choices, and whether public health decisions reflect open, democratic debate or top-down agendas—concerns long raised in critiques of healthism (Crawford, 2006). These tensions are particularly acute in areas of health psychology that deal with morally charged issues, such as substance use, sexuality, and reproductive health. In these contexts, values often come into conflict and must be carefully weighed—sometimes even traded off (Carter et al., 2011; Carter, Cribb & Allegrante, 2012). The following two common ethical dilemmas in health interventions help to illustrate these challenges:

Should individual freedom be restricted to protect health?

Interventions related to smoking, alcohol use, or drug consumption reveal tensions between personal freedom and promoting collective wellbeing. Some argue that competent adults should have the right to make their own health choices, provided they do not harm others. From this perspective, harm reduction approaches—such as needle exchange programmes, methadone clinics, or vaping as a substitute for smoking—are considered to offer pragmatic solutions without coercion (Seedhouse, 2005; Guttman, 2017). Others, however, see illicit drug use as a broader societal threat that undermines social safety and stability, work ethics, and legal order. From this standpoint, minimising drug use is seen as essential to protecting society’s core values (Seedhouse, 2005).

Is it justifiable to use fear, shame, or disgust to motivate behaviour change?

The image above of solemn-looking children labelled as “chubby” or “fat” is from a U.S. campaign on childhood obesity. The campaign targeted caregivers/parents with a combination of messages intended to arouse fear (e.g., “WARNING“, “Chubby kids may not outlive their parents”, and “He has his father’s eyes, his laugh, and his diabetes”), as well as blame, and shame by positioning caregivers as wholly responsible (“Big bones didn’t make me this way. Big meals do, or “Fat kids become fat adults”). This messaging was supported by videos featuring children making painful statements about their weight, for example, a boy gravely asking his mother, “Why am I fat?” (Perry, 2012). Advocates believed these messages would galvanise parents into addressing their children’s health. However, several critics questioned the ethics of victim blaming and the use of guilt and fear, especially without offering a clear solution (Freeman, 2011).

As these examples highlight, health interventions may require decisions about ethical trade-offs—for instance, between individual rights and collective wellbeing, or between persuasion and coercion. While interventions may offer benefits, they can also cause harm, especially when they reinforce stigma, restrict autonomy, or ignore context. Sometimes a “win-win” solution is possible, but often difficult choices must be made. To guide this kind of ethical reflection, practitioners can draw on specific concepts that help evaluate the implications of different health interventions.

Ethical concepts

Ethical concerns can surface at any intervention level, whether the goal is to prevent the onset of disease (primary), detect and address it early (secondary), or limit the damage and promote wellbeing despite chronic conditions (tertiary). It is therefore critical to remain mindful of how well-intentioned strategies may inadvertently harm individuals, undermine autonomy, or reinforce stigmas. Iatrogenic outcomes refer to unintended harm from interventions. Health interventions can sometimes lead to unintended negative consequences, for example:

- fear-based campaigns may cause resistance, fatalistic thinking, or avoidance rather than behaviour change.

- routine screenings can cause distress due to false positives or overtreatment of slow-growing conditions, such as unnecessary cancer surgeries.

- chronic disease management interventions may increase psychological strain if patients feel pressured into invasive monitoring or rigid lifestyle changes.

Avoiding such outcomes requires complex reflexivity. Explicitly identifying ethical concepts provides the basis for explaining and discussing decision making, monitoring and evaluation, and accountability to stakeholders (Carter et al., 2011; Stephens, 2008). Table 3.3.3 provides an overview of some ethical concepts that arise in health interventions that health psychologists may be involved in (highlighted in Guttman’s (1997) discussion).

Table 3.3.3. Ethical Issues in Health Psychology Interventions

| ETHICAL ISSUE |

Example in Health Promotion |

Example in Clinical Practice |

| Coercion: Restrictive policies infringe on freedom of choice | Banning sugary drinks or trans fats without public input | Involuntary psychiatric treatment without patient consent |

| Control: May serve as a means of social or organisational control | Employer health screening policies linked to insurance benefits | Monitoring patient adherence through digital tools without consent |

| Culpability: Unfairly placing blame on individuals or groups | Framing obesity as a personal failure in health campaigns | Blaming patients for their poor outcomes despite structural barriers |

| Depriving: Denying pleasures that others can afford | High tobacco taxes limiting access for low-income groups | Restricting access to certain treatments based on funding or location |

| Distraction: Health focus diverts attention from larger social issues | Focus on personal diet distracts from environmental health issues | Focusing on individual resilience instead of workplace burnout causes |

| Exploitation: Using marginalised groups to deliver services or achieve goals | Relying on community groups to provide services without funding | Expecting cultural navigators or kaumātua to work unpaid |

| Harm reduction: Supporting non-approved behaviours to reduce harm | Needle exchange programmes | Providing opioid substitution therapies like methadone |

| Health as a value (healthism): Promotes moralism at the expense of other values | Glorifying health behaviours over community or cultural values | Promoting ‘health responsibility’ while ignoring trauma or social determinants |

| Labelling: Harm caused by stigmatising or labelling individuals | HIV campaigns portraying people with HIV as dangerous | Labelling patients as ‘non-compliant’ or ‘treatment resistant’ |

| Persuasion: Persuasive strategies may arouse anxieties or fears, be manipulative, or impinge on individual rights | Graphic anti-smoking ads using fear to change behaviour | Using fear-based messaging to promote compliance with psychiatric medication |

| Privileging: Benefits unequally distributed based on social power | Medicalising cholesterol levels to prioritise detection in affluent groups | Private services offering better chronic disease care for those who can pay |

| Promises: Making promises that may not be realistic or beneficial | Messages that imply lifestyle changes guarantee long life | Telling patients treatment will ‘cure’ them when prognosis is uncertain |

| Targeting: Strategies may widen inequalities or ignore cultural relevance | Targeting low-income groups with dietary advice that they cannot act on | Cultural tailoring of interventions that overlook Indigenous worldviews |

Next, I home in on some common concepts that might be used to evaluate the ethical implications of health interventions, namely, stigma, paternalism, and victim blaming. Although these often overlap, for simplicity, I discuss them separately.

Paternalism – interfering “for their own good”

Paternalism, according to Carter, Cribb, and Allegrante (2012, p. 10), “gathers several, usually three, meanings into a single word: interfering with a person’s autonomy or liberty, doing so without their consent, and doing so for their own good. It is possible to justify all of these, depending on our view of a good society, and on the particular case”. Paternalistic interventions are often justified as protecting people from harm, for example, through coercive public health messaging, restricting treatment options, or steering patients toward particular choices. While often framed as benevolent, such practices can undermine trust, particularly when people feel excluded from decisions about their care (Brown, 2018). This is especially problematic for socially marginalised groups (e.g., women, Indigenous peoples, and people of colour) whose concerns are often ignored, dismissed, or pathologised (Barnes, 2015; Heard et al., 2020). For example, McPhail-Bell et al. (2015) show how Indigenous health promotion in Australia can reproduce colonial control, despite claiming to promote empowerment. Thus, “disrupting established norms and ‘expertise’ requires taking the perspective of those populations whose social and health realities remain at the margins” (Hankinsky & Christofersen, 2008, p. 278).

Victim-blaming – ignoring structural barriers

Health interventions can sometimes place undue responsibility on individuals while overlooking broader social determinants. This is evident in:

- health promotion campaigns implying that people choose ill-health simply by failing to exercise or eat well.

- blaming individuals for late diagnoses due to missed screenings.

- labelling certain clients “non-compliant”, without considering contextual or structural barriers (e.g., poverty, inadequate healthcare access, cultural health literacy differences).

This kind of thinking, often called victim-blaming, assumes people have full control over their health and can always make “good choices” if they just try hard enough. Research shows that is not realistic; people’s health is shaped by many factors outside their control, including housing, income, racism, and access to healthcare (Carter et al., 2012). Victim-blaming does not just miss the bigger picture—it can harm the people it is trying to help, and discourage engagement with services. Framing health as a personal responsibility can lead to shame and blame, especially for people living with chronic illness or from marginalised groups (Brown, 2018). For example, mental health workers supporting people with cancer have raised concerns about anti-smoking interventions that focus on individual-level change only. These behaviour-focused interventions create stigma and shame among people with smoking-related illness, even those who never smoked. Some clinicians have, therefore, questioned whether the health benefits of such approaches are worth the personal costs of stigma and blame (Riley et al., 2017). Ethical practice in both health promotion and clinical settings means taking structural barriers seriously and avoiding messages or approaches that suggest people are solely to blame for their health.

Coercion – restricting choice

While coercion is sometimes necessary to achieve public health goals, it can also infringe on individual autonomy. Examples include:

- restricting substances (e.g., sugar taxes or banning alcohol sales).

- pressuring people into screening programmes with urgent-sounding messages that limit informed choice.

- compulsory rehabilitation under the justification of “protecting” patients.

Carter et al. (2011) note that coercion ranges from reasonable to questionable. Of course, what counts as “reasonable” is, as discussed earlier, open to debate. Ideas about what is acceptable or justified often reflect particular values, cultural norms, and assumptions about health, responsibility, and risk. These judgments are not neutral—they are shaped by broader social and political beliefs. Therefore, based on one’s values, unreasonable coercion may involve encouraging negative self-perceptions (e.g., labelling individuals as lazy, irresponsible, or dangerous) or amplifying fear around health risks, even for low-risk individuals. For example, campaigns targeting body weight often use population-level data to suggest that any increase in waist size leads to serious illness, such as cancer or heart disease. This can prompt fear and self-surveillance in people who are not at high risk, encouraging them to see themselves as unhealthy based solely on weight, regardless of their actual health status (Carter et al., 2011).

Stigma and reinforcing social marginalisation

Interventions can stigmatise individuals by portraying them in negative ways and as responsible for their health problems. For instance:

- anti-smoking campaigns that frame smokers as reckless.

- patients declining screenings or struggling with treatment regimens may be labelled as “non-compliant” or “difficult”.

- repeated hospital admissions may result in patients being seen as lacking insight rather than acknowledging systemic issues affecting recovery.

- health psychology practitioners must be cautious not to reinforce biases or present individuals as burdens on healthcare systems.

Discussing this issue in the context of anti-smoking campaigns, Riley et al (2017) assert, “There is an ethical burden for creators of public health campaigns to consider lung cancer stigma in the development and dissemination of hard-hitting anti-tobacco campaigns. We also contend that health care professionals have an ethical responsibility to try to mitigate stigmatizing messages of public health campaigns with empathic patient-clinician communication during clinical encounters”. These comments apply to other health issues where stigma is used to try to promote behaviour change. Weight management is a good example, as shown in the following example.

An example: Applying ethical concepts to “How do you measure up?” campaign video

The Australian social marketing campaign How Do You Measure Up?, which targeted adult weight through mass media messaging, provides a good example of ethical concepts in practice. While social marketing campaigns like this represent only a fraction of health promotion efforts, their high visibility and resource intensity make them particularly worthy of scrutiny (Carter et al., 2011). Below is a television advertisement from the campaign. As you watch it, think about what ethical issues their approach raises.

Carter and colleagues argue that this campaign relied on coercive and stigmatising tactics—framing weight as a personal failing, appealing to parental guilt, and encouraging self-surveillance. Lupton (2015) critiques this campaign (and others like it) for using what she calls the “pedagogy of disgust,” in which shame and revulsion are deliberately evoked to influence behaviour. These strategies raise serious ethical concerns about autonomy, dignity, and unintended harm, particularly for people already marginalised due to body size, socioeconomic status, or health history (Warbrick, et al., 2019). In this vein, Warbrick et al.’s (2019) work shows how obesity prevention campaigns rely on fat-shaming tactics that disproportionately target Māori, reinforcing stigma and colonial narratives of personal failure. These approaches not only ignore structural conditions like food insecurity or racism in healthcare, but also cause harm by deepening shame and marginalisation.

Similar ethical concerns can also arise in clinical contexts—such as when weight is treated as the primary health concern without considering broader social, psychological, or metabolic factors. Interventions that fail to engage with patients’ lived realities may risk reinforcing stigma or overlooking structural barriers to health. As discussed in Chapter 2.2, this narrow framing can overlook cultural understandings of health and body size, reinforce stigma, and sideline structural issues. Failing to engage with patients’ lived realities may risk undermining trust and causing harm, even when well-intentioned.

Theoretical assumptions: using theory reflexively in practice

In addition to values and ethics, health psychology interventions are shaped by theoretical assumptions—often implicitly. Being reflexive about the theories used helps clarify goals, illuminate the complexity of health issues, and anticipate the social and political effects of one’s work. The reflexive use of theory helps:

- guide practitioners’ understanding of health issues and their targets for change.

- clarify the complexities of health-related behaviours and practices.

- incorporate insights about social systems, structures, and contexts.

- encourage critical reflection on assumptions, professional roles, and responsibilities (Stephens, 2008).

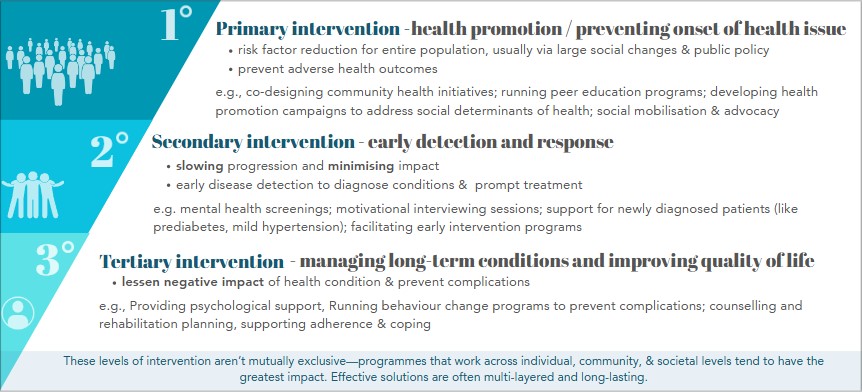

Stam (2000, p. 274) argues that the explicit use of theory “is one of the most crucial steps of our entry into the world of health, disease and illness precisely because it establishes nothing less than our political, epistemological and moral grounding. It also establishes our responsibility as professionals who intervene in the lives of others.” The theoretical lens used to understand a health issue—specifically, what is considered to determine good or poor health—shapes the intervention design. Defining intervention targets involves deciding who or what the intervention will focus on (Nutbeam et al., 2010). As discussed earlier (see Table 3.3.1), this corresponds with different levels of intervention: individual, interpersonal, community, and societal. For instance, supporting children with diabetes might focus on individual behaviour change, family dynamics, school policies, community resources, or broader policy measures, or a combination of these. The figure below also provides a detailed summary.

To illustrate, consider the following two Australian interventions based on evidence generated using two different theories, as summarised in Table 3.3.4:

- The Active Teen Leaders Avoiding Screen-time (ATLAS) intervention for teen-aged boys (12 – 14 years old) that used socio cognitive theory (Smith et al., 2014); and

- The Be Active Eat Well (BAEW) programme for children (4 – 12 years old) that took a socio-ecological approach (Sangiorski et al., 2008; Waters et al., 2011).

Table 3.3.4. Comparison of health promotion interventions for children’s weight

|

Intervention |

ACTIVE TEEN LEADERS AVOIDING SCREEN-TIME (ATLAS) – Smartphone obesity prevention trial |

BE ACTIVE, EAT WELL (BAEW) – Community capacity-building programme promoting healthy eating and physical activity. |

|

Theoretical basis |

Social-cognitive |

Socio-ecological |

|

Core Assumptions (based on theory) |

|

|

|

Rationale |

If children are informed about negative health effects and given enjoyable alternatives, they will adopt healthier behaviours. |

Children’s behaviour change occurs by addressing both individual actions and broader social/physical environments. |

|

What must change? |

Children’s lifestyle behaviours:

|

Children’s behaviours + wider (physical and social) environment:

|

|

Targets |

Individual children, teen-aged boys in low-income communities |

Children aged 4 to 12 years within their communities (multi-level approach) |

|

Strategies |

Self-monitoring, goal setting, and education |

Combining behaviour-focused strategies with supportive changes in the physical and social environment. |

|

Key acknowledgements |

|

|

|

Limitations |

|

|

This example shows how a socio-cognitive approach assumes that health issues stem from individuals’ or groups’ modifiable behaviours, attitudes, or beliefs. This implies that change can be achieved by altering these factors through education, skill-building, or environmental adjustments. Accordingly, the Active Teen Leaders Avoiding Screen-time intervention focused mainly on individuals and interpersonal influences. In contrast, socio-ecological models recognise that health determinants operate at multiple levels, from individual behaviours to social relationships, institutional policies, and broader socio-political structures (Signal et al., 2013). Hence, the Be Active, Eat Well programme took a multi-level approach, targeting these interconnected layers rather than solely focusing on individual choices.

As Table 3.4.4 highlights, the approaches taken in both interventions have limitations. This is because each theoretical frame offers a particular and partial perspective on an issue. No theory is perfectly complete. These limitations are made explicit through reflexive engagement with theory, encouraging critique and improvement. Reflexivity allows practitioners to acknowledge the knowledge and assumptions underlying their approach, fostering openness to alternative perspectives (Stam, 2000; Nutbeam et al., 2010).

The use of reflexive theory can help ensure that the approaches taken align with the values, needs, and experiences of affected individuals, groups, or communities. This is particularly evident in an example of suicide prevention efforts for Indigenous communities. Mainstream prevention models often focus on individual risk factors, neglecting broader cultural and historical determinants of wellbeing. The continued higher rates of suicide among Indigenous communities than their non-Indigenous counterparts suggest a need for more holistic interventions that incorporate Indigenous culture (Sones et al., 2010). Reflexivity is needed in theoretical framing to allow for participatory design and cultural safety and generate more effective and empowering mental health interventions for Indigenous communities. Some examples of such approaches include the culture-based framework for mental wellbeing within Manitoba First Nations communities, which employs community-based participatory research to co-create interventions with First Nations leaders, incorporating relational approaches, land-based healing, and Indigenous governance over mental health services (Kyoon-Achan et al., 2018). Similarly, Australia’s Social and Emotional Well-being Model was developed through participatory action research with multiple Indigenous communities, affirming cultural knowledge and promoting collective healing and relational resilience (Dudgeon, 2020).

Summing up

Values, ethics, and theoretical assumptions all play a central role in shaping how health psychologists understand problems and design interventions. Together, they guide decision making about what should be done, why, and how. Being explicit about ethical considerations can help practitioners explain and justify their choices, especially in contexts where decisions may affect marginalised or vulnerable groups. Ethical frameworks must be sensitive to local contexts, taking seriously the material conditions and lived realities of the people most affected. This ensures that interventions are relevant, equitable, and unlikely to cause unintended harm. (Remember the cobra effect!) Similarly, theoretical assumptions—often operating implicitly—shape how health issues are defined and what kinds of change are prioritised. Reflexively engaging with theory helps practitioners clarify their goals, anticipate consequences, and align their strategies with the values and needs of communities (Stephens, 2008; Prilleltensky & Nelso, 2017). Professional competency in critical health psychology, therefore, requires a commitment to ongoing reflection on personal, ethical, and theoretical standpoints. This reflective approach establishes clear, intentional standards for practice—helping to ensure that interventions are not only evidence-informed, but also socially just and contextually responsive (Health Promotion Forum, 2012).

Designing and implementing interventions: turning definitions into practice

Applying interventions in real-world settings requires balancing evidence-based practice, community perspectives, policy constraints, and professional judgment (Stephens, 2008). This section explores how health interventions are defined, planned, and implemented through two case studies of HIV/AIDS interventions: the SiRCHESI Project in Cambodia and the Sonagachi Project in India. Both illustrate the importance of culturally and ethically informed decision making in community and multilevel health promotion efforts.

Lessons for health psychology and intervention design

Both the SiRCHESI and Sonagachi projects illustrate the value of contextualised, participatory, and multi-level approaches in health promotion interventions. They highlight:

- the necessity of integrating social, economic, and cultural considerations into health interventions (Kerrigan et al., 2006).

- the power of community-led strategies, where those most affected actively shape solutions (Dasgupta, 2009).

- the importance of structural empowerment, ensuring sustainable, systemic changes that support marginalised populations (Nag, 2005).

These case studies reinforce that effective intervention occurs at all levels, from individual behaviour change to systemic inequalities, to create enabling environments for lasting health improvements (Signal et al., 2013).

The SiRCHESI Project: a participatory approach to HIV/AIDS prevention in Cambodia

The Siem Reap Citizens for Health, Educational, and Social Issues (SiRCHESI) project exemplifies a participatory framework for addressing community health issues in ways that are meaningful to local populations. Founded as an evidence-driven grassroots NGO, SiRCHESI employed Participatory Action Research (PAR) to combat HIV/AIDS in Siem Reap. Over time, the initiative significantly reduced transmission rates, particularly among high-risk groups such as beer sellers (Lubeck et al., 2014).

Background and health issue

Siem Reap, a major tourist hub in Cambodia, was severely affected by the HIV/AIDS epidemic, with some of the highest infection rates in Southeast Asia. The crisis was fueled by sex tourism, poverty, workplace exploitation, and limited access to healthcare, disproportionately affecting women in precarious employment, such as beer promotion and massage services. At the start of the intervention in 2000, 42% of brothel-based sex workers and 20% of beer sellers tested positive for HIV (Stephens, 2008). The following video (supplied by Ian Lubeck) provides the background to this issue, focusing on the beer sellers.

The crisis was shaped by historical and socio economic factors. Many young Cambodian men had lost their parents during the Pol Pot genocide, which disrupted traditional marriage customs and led to an increase in visits to brothels (Lubeck, 2008). Simultaneously, women with limited education and employment opportunities were funnelled into the entertainment industry, including beer promotion, where low wages and economic necessity led many to engage in sex work for additional income (Lee et al., 2010).

Intervention strategies and theoretical basis

SiRCHESI adopted a multi-sectoral, empowerment-based approach that addressed individual, social, and structural determinants of health. Hence, the aim was to reduce the spread of HIV in Siem Reap by tackling underlying social inequalities in literacy, employment, poverty, and HIV/AIDS mortality risks. These aims generated specific objectives at different levels:

- individual behavioural change: 100% condom use for those at risk of HIV infection.

- social development: peer support, literacy education, and employment opportunities.

- economic development: Improving local employment conditions.

- political change: Lobbying the government and advocating for corporate responsibility.

Lubeck et al. (2014) described the following strategies used in the programme:

- peer education and health workshops to build knowledge, raise critical consciousness (or conscientisation), and promote safe practices.

- economic empowerment through literacy training and job skill development (helping women transition into safer employment.

- workplace advocacy to improve labour laws and working conditions for beer promoters.

- challenging negative social, community and global structures (e.g., lobbying multi-national beer companies).

In addition, “SiRCHESI constantly conduct[ed] research, so that programme decisions can be informed by evidence/evaluations, as part of the PAR [Participatory Action Research] framework” (Lubeck et al., 2014, p. 111).

A key innovation was the Hotel Apprenticeship Programme, which originated from the finding that many Cambodian women had been denied jobs in hotels due to a lack of job skills, Khmer literacy, and conversational English, turning to beer promotion as a result. The programme provided literacy, English language training, and professional skills to help beer sellers secure safer, higher-paying jobs in the hospitality industry (Lee et al., 2010; Lubeck et al., 2014). This initiative highlights the connection between economic security, social empowerment, and health outcomes (Carr, 2019). The video below shows some highlights from the author. (Video kindly supplied by Ian Lubek. Credit: Ian Lubeck and Brett Dickson.)

Stephens (2008) explains how these strategies occurred at various levels of change, addressing both immediate individual risks and broader social and economic conditions that contribute to vulnerability to sexually transmitted infection, as summarised in Table 3.3.5.

Table 3.3.5. Strategies and Levels of Intervention

|

Individual and community level |

Community and local institutional level |

|

|

The Sonagachi Project: a sustainable HIV/AIDS intervention in India

The Sonagachi Sexually Transmitted Disease (STD)/HIV Intervention Program (SHIP) is a globally recognised community health initiative that transformed the lives of sex workers in Kolkata, India. Originally a small-scale intervention, it evolved into a sustainable, peer-led programme that empowered sex workers to take collective action in reducing HIV vulnerability (Dasgupta, 2009).

Background and health issue

With high HIV rates among brothel-based sex workers, Sonagachi’s intervention sought to reframe HIV as an occupational health issue and empower sex workers to advocate for safer working conditions (Bandyopadhyay et al., 2002). The programme engaged over 4,000 sex workers alongside government and non-governmental organisations to research, design, and implement a comprehensive health intervention (Gooptu & Bandyopadhyay, 2008).

Intervention strategies and theoretical basis

The Sonagachi Project moved beyond individual behaviour change approaches (e.g., condom promotion) to focus on environmental and structural factors that shape health risks (Kerrigan et al., 2006). Applying community development theories, the project redefined HIV/AIDS as a shared community issue requiring collective action and dialogue rather than solely an individual responsibility (Dasgupta, 2009). The focus of the intervention thus shifted from individual sex workers’ failure to prevent sexually transmitted infections to the wider context where they work and the community that this work is part of (Campell & Cornish, 2012; Stephens, 2008).

Accordingly, intervention followed a multi-level empowerment approach, working at individual, group, and structural levels to address the broader conditions contributing to HIV risk (Campell & Cornish, 2012; Dasgupta, 2009; Newman, 2003), as shown in Table 3.3.6. The specific strategies that were used included:

- peer outreach and participation, with sex workers leading education and advocacy efforts (Newman, 2003).

- human rights and labour protections, positioning sex work as legitimate employment deserving of occupational safety measures (Kerrigan et al., 2006).

- community development and social solidarity, fostering collective empowerment through worker-led organisations (Bandyopadhyay & Banerjee, 1999).

Evaluations identified the following strategies implemented by the Sonagachi Project as key to increasing the collective ability of sex workers to reduce their vulnerability:

- facilitating a sense of community among sex workers through community meetings, fairs, and protests.

- increasing access and control over material resources via micro-credit and cooperative banking.

- facilitating social acceptance of sex workers by actively involving sex industry and civil society stakeholders.

- decreasing perceived powerlessness among sex workers through capacity-building workshops and seminars (Bandyopadhyay et al., 2002).

Table 3.3.6. Empowerment Strategies by Level of Change

| Individual Empowerment |

|

|---|---|

| Group Empowerment |

|

| Structural Empowerment |

|

Outcomes and global recognition

The Sonagachi Project successfully lowered HIV rates among sex workers and increased their collective bargaining power. It received international acclaim, with UNAIDS recognising it as a “best practices” model for community-led HIV prevention (Newman, 2003). A crucial factor in its success was the active leadership of sex workers, who played a central role in designing and sustaining the intervention (Bandyopadhyay et al., 2002).

Conclusion

This chapter has explored the complexities involved in defining health problems and designing interventions, showing that professional practice in health psychology is never neutral. It is shaped by values, power dynamics, ethical frameworks, and theoretical assumptions—each of which influences who gets help, how, and with what consequences.

By taking a critically reflexive approach to practice, health psychologists can make more intentional, ethical, and socially responsive decisions. Reflexivity helps surface hidden assumptions, question dominant models, and create space for alternative knowledges and community-driven solutions.

Ultimately, interventions rooted in critical health psychology aim not just to reduce risk or change behaviour, but to promote wellbeing and liberation in ways that are culturally grounded, participatory, and just. As the field continues to evolve, practitioners must remain open to discomfort, committed to reflection, and attuned to the broader social and structural contexts in which they work.

Takeaway points

- A critical lens advances justice – critical health psychology encourages practitioners to challenge dominant narratives, promote inclusivity, and work toward structural change.

- Defining health problems is not neutral – the identification and framing of health issues are shaped by cultural, social, political, and ethical factors.

- Intervention is never neutral – all interventions reflect particular values, worldviews, and power dynamics. Recognising this helps practitioners act with greater accountability and care.

- Practitioners are not outside the system – health psychologists are shaped by the same social norms, structures, and power relations they aim to address. Reflexivity involves locating oneself within this context.

- Unintended consequences are common – even well-intentioned interventions can backfire if they overlook context, power dynamics, or the perspectives of those most affected.

- The power of framing – how a health issue is defined and understood shapes decisions about who or what should change and what strategies are considered legitimate.

- Reflexivity is essential – health psychology practitioners must critically reflect on their assumptions, values, and theoretical frameworks to ensure ethical and contextually relevant interventions.

- Reflexive use of theory strengthens practice – applying theory consciously and critically helps practitioners design thoughtful, effective, and accountable interventions.

- Ethical practice involves navigating tensions – practitioners often face competing priorities and must make difficult choices. A critical perspective supports transparent, principled decision-making.

- Ethical and cultural safety considerations matter – practitioners must engage with ethical principles, cultural safety, and (in Aotearoa New Zealand) Te Tiriti o Waitangi commitments to avoid reinforcing inequities or causing harm.

- Match the strategy to the level – effective interventions require clarity about whether change is needed at the individual, interpersonal, organisational, or systemic level—or across multiple levels.

- Participation and equity strengthen impact – interventions co-designed with affected communities—especially marginalised groups—are more likely to be effective, ethical, and empowering.

Learn more

Further reading

- Ahuriri-Driscoll et al., (2025). Cultural safety in health: Professional practice, pedagogy & research. Queensland University of Technology. https://doi.org/10.5204/book.eprints.25

- Psychologists are guided by ethical principles and codes of conduct to ensure responsible and ethical practice, encompassing areas like beneficence, fidelity, integrity, justice, and respect for rights. For example, the American Psychological Association (APA) publishes the Ethical Principles of Psychologists and Code of Conduct detailing aspirational principles and enforceable standards that U.S. American psychologists should use when making decisions. To find your country’s code, visit your local professional board’s website.

Multimedia

- Watch Isaac Prilleltensy’s highly engaging TED Talk “Community Well Being: Socialize or Social-Lies“

- Watch the following video in which researchers Puhl, Reudicke, and Peterson (2013) systematically assess public perceptions of obesity-related public health campaigns in the USA. Their findings on the effectiveness of using stigma and shame in health promotion communication are discussed in the video.

Full image description of Figure 3.3.5. Infographic showing three levels of health psychology intervention: Primary intervention (health promotion and prevention): focuses on reducing risk factors and preventing illness through actions like community co-design, peer education, and addressing social determinants. Secondary intervention (early detection and response): involves slowing disease progression and diagnosing conditions early—for example, mental health screenings or support for newly diagnosed patients. Tertiary intervention (managing long-term conditions): aims to lessen the impact of chronic illness and improve quality of life through psychological support, behaviour change programs, and rehabilitation. The infographic notes that these levels are not mutually exclusive, and that programmes working across individual, community, and societal levels tend to have the greatest impact. [Back to figure]

References

Bandyopadhyay, N,. et al. (2002, July). Operationalizing an effective community development intervention for reducing HIV vulnerability in female sex work: Lessons learned from the Sonagachi project in Kolkata, India [Poster presentation]. International Conference on AIDS, Barcelona, Spain.

Bandyopadhyay, N., & Banerjee, B. (1999). Sex workers in Calcutta organize themselves to become agents for change. Sexual Health Exchange, (2), 6–8.

Barnes, B. R. (2015). Critiques of health behaviour change programmes. South African Journal of Psychology, 45(4), 430–438. https://doi.org/10.1177/0081246315603631

Bartholomae, F. W., & Stumpfegger, E. (2021). Government interventions during the Coronavirus pandemic – A critical consideration. CESifo Forum, 22(5), 37–42. https://hdl.handle.net/10419/250940

Bolam, B., & Chamberlain, K. (2003). Professionalization and reflexivity in critical health psychology practice. Journal of Health Psychology, 8(2), 215–218. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105303008002661

Brown, R. C. H. (2018). Resisting moralisation in health promotion. Ethical Theory and Moral Practice, 21(4), 997–1011. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10677-018-9941-3

Burman, E. (2003). From difference to intersectionality: Challenges and resources. European Journal of Psychotherapy & Counselling, 6(4), 293–308. https://doi.org/10.1080/3642530410001665904

Came, H. (2014). Sites of institutional racism in public health policy making in New Zealand. Social Science & Medicine, 106, 214–220. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.01.055

Came, H., & Tudor, K. (2016). Bicultural praxis: The relevance of Te Tiriti o Waitangi to health promotion internationally. International Journal of Health Promotion and Education, 54(4), 184–192. https://doi.org/10.1080/14635240.2016.1156009