1.1 Hauora

Eleanor Brittain and Aorangi Kora

Overview

Cultural understandings inform how we think about people and their health. In this chapter we introduce Māori cultural understandings of health and wellbeing, with specific considerations for critical health psychology. We begin by presenting Māori worldviews and knowledges and discuss how these inform Māori notions of wellbeing. We examine the historical and socio-political context in Aotearoa New Zealand, with a focus on Te Tiriti o Waitangi, and consider the ways contexts shape how we think about people and their health. Subsequently, we outline Māori models of health and then concentrate on specific dimensions of wellbeing for Māori, with relevant examples of application for contemporary health psychology.

The topics in this chapter are not new concepts, however discussing them here offers opportunities and possibilities to critically consider and re-conceptualise health psychology. These issues are equally important for all who study, teach, research, and engage with critical health psychology in Aotearoa New Zealand. Although our focus is on Māori worldviews and foundational understandings for those working in Aotearoa New Zealand, this chapter also serves a broader remit of sharing knowledge for people interested in decolonising psychology. We recognise the potential for Māori understandings to enrich and extend critical health psychology, which may in turn be influential to cultural contexts globally.

The questions we address in this chapter are: How do Māori worldviews and experiences inform their conceptualisations of health? How can critical health psychology engage appropriately with Māori knowledges and perspectives? We focus on the following learning objectives:

Learning objectives

- Explore Māori worldviews and knowledges and evaluate their relationship to Māori understandings of health and wellbeing.

- Recognise the importance of historical and socio-political context, including key events in the history of Aotearoa New Zealand, and discuss the impacts for Māori health.

- Review Māori models of health and dimensions of wellbeing and examine their application and relevance for contemporary health psychology.

Positionality

Positionality is important from the standpoint that all knowledge and research is inherently subjective, as we all view and understand the world through our own cultural lenses. We recognise and acknowledge the cultural assumptions we hold about reality, what we deem as constituting knowledge, and how these assumptions inform the processes we use in research and in practice. Māori are not a homogenous people, and the perspectives presented in this chapter are shaped by the authors’ own worldviews and lived experiences, hapū and iwi affiliations, educational backgrounds and academic experiences, gender, socioeconomic status, and more (see positionality statements in the Introduction to the book). Therefore, based on our understandings of Māori worldviews, and drawing together various discussions from the areas of Māori psychology and Māori health, the perspectives we offer are intended to offer a broad coverage. Our aim is to encourage critical thought to shape a new, or renewed, appreciation for Māori health moving forward.

Māori notions of health and wellbeing – What is hauora?

Māori notions of health and wellbeing are holistic, relational, and grounded in Māori cultural worldviews. Sir Mason Durie, a respected leader in Māori health, emphasises cultural connection as foundational to Māori health:

Platforms for Māori health are constructed from land, language and whānau; from marae and hapū; from Rangi and Papa; from the ‘ashes of colonisation’; from adequate opportunity for cultural expression; and from being able to participate fully within society. Like other New Zealanders Māori are not immune from the effects of unhealthy policies, nor from unacceptable standards of living, but all too often Māori have encountered expectations that they should abandon a Māori base. Yet being Māori itself is a foundation for health. (Durie, 2001, pp. 35-36).

Health and wellbeing are conceptualised within several te reo Māori terms:

- Hauora describes the breath of life and spirit; it refers to a physical sense of wellbeing for an individual and it is interdependent with collective qualities such as whanaungatanga (Henare, 1988; Pihama et al., 2023).

- Mauri ora represents the life-giving essence, the spark and vitality of life that binds the spiritual and physical (Barlow, 1991; Mead, 2016).

- Waiora encompasses total wellbeing and strength of spirit, denoting flowing and life-sustaining waters, and has bases in Māori creation narratives (Pere, 1997).

- Whānau ora pertains to family and collective wellbeing and it is a term promoted in contemporary Māori health policy (Ministry of Health, 2024).

We have chosen to call this chapter Hauora, to reflect the connection between the physical, psychological, relational, and spiritual.

Māori beliefs about the universe, reality, and knowledges

Māori have distinct and unique ways of being and thinking in the world. Māori beliefs about the universe, reality, and knowledges emphasise relational and spiritual understandings; there is an inherent interconnectedness between all things. In this section we describe these worldviews and assumptions from te ao Māori and discuss how they are relevant to Māori perspectives and experiences of health.

Cosmologies and cosmogonies

Cosmologies encompass beliefs about the nature of the universe and cosmogonies are understandings of the origins of the universe. Māori cosmologies and cosmogonies are multiple and rich. Commonly they describe the creation of the universe and the emergence of life in three phases: te kore, te pō, te ao mārama.

- Te kore is the most distant phase in time, the beginning. Te kore is the source of all life, meaning “the void” or “nothing”. However, te kore is also understood as energetic and the space of infinite potential.

- Te pō is the second phase. Te pō, meaning “darkness”, refers to periods of time and gradations of perceptual and mental darkness. Te pō is described as the realm of becoming, with the development of earth and life. To Māori, atua are also considered to be tīpuna and during te pō, Papatūānuku and Ranginui, who are regarded as primordial atua, come into existence. They procreate many more atua, but the closeness of their embrace prevents light and growth. The children grow tired and rebel, plotting against their parents to separate them. The separation is achieved by Tāne, who let light into the world.

- Te ao mārama is the third phase and from darkness comes the world of light. This is the realm in which human life and life on earth develops. In te ao mārama there is space for growth and the pursuit of knowledges and physical and mental enlightenment is possible. Humankind comes into being when Tāne shapes the first woman, Hine-ahu-one, from the Earth.

(To read more, see our sources: Barlow, 1991; Marsden, 1992; Mead 2016; Walker 1992).

While this is a summary of extensive knowledges and a sole perspective, what it shows is that Māori creation narratives provide the basis for understanding and interpreting reality and give meaning to everyday life.

Ontologies

Ontologies refer to understandings about reality and human nature. Based on Māori narratives about the origins and nature of the universe, Māori ontologies emphasise connectedness, relationships, and a spiritual element. These are established within cultural concepts:

- Whakapapa means genealogy, although more specifically it refers to layers of genealogy. Māori narratives and whakapapa describe human life as descending from atua, and as therefore related to the natural environment. Whakapapa is the structure by which all things are connected (Barlow, 1991).

- Whanaungatanga refers to relationships and kinship. These concepts highlight connections between the natural world, atua, tīpuna, and humankind. Whanaungatanga encompasses collective interdependence (Henry & Pene, 2001).

- Wairua and recognition of the spiritual and unseen is also central to Māori assumptions about reality and human life. Wairua is described as the ultimate reality of existence for Māori (Marsden, 1992).

Taken together, Māori cosmologies and ontologies view human life as emanating and descending from the universe and from atua. These worldviews emphasise interconnectedness between everything in existence, on earth, and in the universe. Importantly, we recognise our existence as part of a whole, spanning physical and spiritual, across past, present, and future. Existence does not begin, nor does it end, with us.

Epistemologies

Epistemologies entail undertandings about the nature of knowledges. Just as whakapapa is centred in Māori ontologies, whakapapa is also significant to Māori epistemologies as a means by which Māori record, remember, and impart knowledges about the world (Barlow, 1991). In this way Māori epistemologies and ways of engaging with knowledges reinforce the connectedness between human kind, the environment, and to space, in temporal and spiritual terms (Smith, 2008).

Similarly, Māori use narratives and metaphor to preserve and communicate knowledges. These narratives are often referred to as pūrākau, and use of pūrākau encourages multiple meanings and interpretations (Lee-Morgan, 2019). Narratives and the knowledges they contain reflect a uniqueness derived from the pūrākau inherent to whānau, hapū, and iwi.

Recapping cosmologies and cosmogonies, ontologies, and epistemologies from a Māori perspective

By cosmologies and cosmogonies we mean understandings about the nature and origins of the universe. Te kore, te pō, and te ao mārama are common representations for Māori of the creation of the universe and life.

By ontologies we mean understandings about the nature of reality and human nature. From a Māori perspective this is relational and underpinned by whakapapa and whanaungatanga.

By epistemologies we mean understandings about the nature of knowledges. Whakapapa and pūrākau are significant to Māori ways of recording, preserving, and communicating knowledges.

You can also see Riley et al. Chapter 1.3 for further discussion of these “ologies”.

Want to know more about Māori creation stories and worldviews?

- Read: Te Ahukaramū Charles Royal on Te Ara: https://teara.govt.nz/en/maori-creation-traditions

- Watch: Kiri Prentice (Ngai Tūhoe, Ngāti Awa), Psychiatrist and creator of Māori Minds – a brief video on, An Ontology of Whanaungatanga

Mātauranga

With a foundational understanding of Māori beliefs about the universe, reality, and knowledges, we now focus on Māori knowledges more intently. Mātauranga is often used as a term for knowledges and it is described as:

- a contemporary phrase for a body or continuum of knowledges with age-old origins.

- referring to something unique and valuable about the Māori world (Royal, 2012).

In exploring tikanga and a range of Māori practices, Sir Hirini Moko Mead, a leading Māori scholar, emphasises the sheer breadth of mātauranga:

The term “mātauranga Māori” encompasses all branches of Māori knowledge, past, present and still developing. It is like a super subject because it includes a whole range of subjects that are familiar in our world today, such as philosophy, astronomy, mathematics, language, history, education and so on. And it will also include subjects we have not yet heard about. Mātauranga Māori has no ending: it will continue to grow for generations to come. (Mead, 2016, p. 245).

Examples of mātauranga in Māori traditions and customs include pūrākau, whakataukī, karakia, waiata, mōteatea, and rongoā. We also do not need to look far to see mātauranga as continuing to develop in our contemporary context. The growth of Māori scholarship across academic disciplines, including health psychology is one example, and in the public sphere the revitalisation of mātauranga about Matariki and associated Māori practices is another.

Mātauranga has often been dismissed and undermined by Western science and researchers (for discussion of a recent issue, see Stewart, 2021). However, Māori worldviews and mātauranga have been, and continue to be, valid. Indeed mātauranga is relevant and drawn on in research and practice in contemporary health settings. For example, in a surgical outpatient setting a collaborative treatment approach was used by Koea et al. (2024) to implement rongoā practices alongside routine Western medical practice. Rongoā and Māori healing traditions are founded in mātauranga and this feasibility study identified factors to promote effective collaboration of knowledges and practices from Māori and Western perspectives in a health setting in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Kaupapa Māori

Kaupapa Māori is embedded in Māori worldviews, philosophies, and mātauranga. It takes for granted the validity and legitimacy of Māori knowledges, culture, and te reo Māori. Kaupapa Māori is essentially related to being Māori (Nepe, 1991; Smith, 2021). We can view mātauranga as labelling knowledges and as informing Kaupapa Māori (Pihama, 2010). However, whereas mātauranga does not infer any particular action, Kaupapa Māori indicates action based on tikanga and practices (Royal, 2012).

The eminent example of Kaupapa Māori in action is the establishment of alternative forms of education for Māori, Te Kōhanga Reo and Kura Kaupapa Māori. In the 1980s there was growing political consciousness among Māori, including increased energy to recognise Te Tiriti o Waitangi, and the revitalisation of te reo Māori. The developments in Kaupapa Māori education became a symbol of Māori efforts to embody tino rangatiratanga (Smith, 2017).

For Linda Tuhiwai Smith the implications of Kaupapa Māori are substantial:

There is more to Kaupapa Māori than our history under colonialism or our desires for self-determination. We have a different epistemological tradition, one which frames the way we see the world, the way we organize ourselves in it, the questions we ask and the solutions that we seek. It is larger than the individuals in it and the specific ‘moment’ in which we are currently living. (Smith, 2021, p. 244).

The term Kaupapa Māori theory emphasises Māori cultural ways and knowledges, and Graham Hingangaroa Smith (2017) is clear that Kaupapa Māori theory is transformative. Specifically, it is transforming praxis, which means it involves a cycle of consciousness raising, resistance, and transformative action. In other words, Smith asks, “How is your theorising work linked to tangible outcomes that are transformative?” (p. 70). To be of benefit to Māori, Kaupapa Māori theory must be connected to Māori lived experiences and be focused on practice and transformative outcomes (Pihama, 2010).

A whānau-led project in cancer research

A prime example of Kaupapa Māori in action is seen in an innovative partnership between members of the McLeod whānau and their community, geneticists, and clinicians. Spanning almost 30 years, together they identified a genetic mutation that was causing members of the McLeod whānau to die from stomach cancer at a young age. In our view what makes this project Kaupapa Māori is that it was initiated by whānau and has been led by whānau throughout, with a commitment to improving whānau health outcomes. Components of the project have also incorporated Māori knowledges, te reo Māori, and tikanga to inform work with whānau Māori throughout Aotearoa New Zealand, in order to provide better services in care.

Watch: Karyn Paringatai, My whakapapa saved my life.

Kaupapa Māori theory challenges prevailing Western methods of defining, accessing, and creating knowledge about Māori, with Māori maintaining autonomy over the research agenda (Bishop, 1998). Māori cultural specificities, preferences, and practices warrant that Kaupapa Māori theory retains cultural relevance and reverence (Irwin, 1992). Kaupapa Māori theory is inherently critical; it critiques systems of power and unequal power relations (Smith, 2017).

A tradition within Western science and research focused on preserving colonial values and interests, that has undermined Māori knowledges and displaced Māori lived experiences. These oppressive practices have denied Māori agency, authority, and voice (Bishop, 1998). Routinely positioned as “objects” and “others” in research, Māori have been dehumanised and pathologised, where Māori knowledges have been treated as a commodity for colonial exploitation, just as natural resources have been. Decolonisation in research therefore entails centring Māori worldviews and concerns, and engaging in research from a Māori perspective, for purposes that are relevant to Māori (Smith, 2021).

Want to hear directly from the leaders of Kaupapa Māori about its development?

Watch: An online kōrero between Professor Linda Tuhiwai Smith and Professor Leonie Pihama. Kaupapa Māori theory and methodology series 06 04 2020

Historical and socio-political contexts

As well as cultural worldviews, historical and socio-political contexts also play a role in how we understand and respond to hauora for Māori in contemporary settings. Like Māori approaches to health, critical health psychology also understands health as produced through wider historical, social, political, and economic contexts. Both are therefore concerned with social justice agendas.

The history of Aotearoa New Zealand and colonisation have had significant impacts on the state of Māori health today. By drawing attention to the contexts that shape hauora, we can frame and interpret health issues differently. What if we stopped seeking solutions to “fix” people, and instead shifted the focus to consider people’s environments and contexts as being “sick” and needing to be fixed? This kind of approach encourages us to critically think about health experiences as natural or understandable responses to environments and wider contexts that are harmful, rather than attributing issues solely to individuals.

The historical context of Aotearoa New Zealand

For a fuller appreciation of hauora and health experiences for Māori today, it is vital that we have an accurate understanding of history. Surely a basis of knowledge about the historical and social context of Aotearoa New Zealand is critical to critical health psychology.

Early history of Māori and European settlement in Aotearoa New Zealand

To set the scene, there are some key dates and historical events to know about that contribute to the story of Aotearoa New Zealand as nation. Around AD 800 to 900 vogayers from Polynesia navigate Te Moana Nui a Kiwa in double-hulled sailing vessels and begin to settle in Aotearoa New Zealand. These Polynesian voyagers are the ancestors of Māori and settlements are established in favourable sites throughout the North and South Islands. Māori were living here for at least 800 years before the arrival of Europeans.

In 1642, the first European ship visited, captained by Abel Tasman. It would then be almost 100 years until another European vessel arrived in Aotearoa New Zealand, with James Cook first visiting in 1769, and a second time in 1773. Subsequently early visitors to Aotearoa New Zealand sought trade and included seal-hunters, timber traders, and whaling ships. In this early phase of contact, there were major economic benefits for Māori and European visitors alike. However, with visitors came the introduction of contagious diseases and Māori did not have immunity. From around 1790 there were several epidemics that severely impacted Māori. Introduced diseases and intensified fighting with muskets amongst Māori in the 1820s contributed to a decline in the Māori population.

Missionaries introduced Christianity from 1814. Based on ideas of ethnic and cultural superiority, missionaries were motivated to “civilise” Māori. With the first Bible scriptures printed in 1827, Māori demonstrated a keen interest in literacy, with children and adults alike attending mission schools to learn. However, conversion to Christianity negatively impacted Māori culture and customary practices.

Since the visits of explorers in the eighteenth century, hundreds of British and people of other nationalities had settled in Aotearoa New Zealand. By the mid-1830s there were increasing encounters between Māori and Europeans, bringing together peoples with contrasting ways of viewing and relating to the world. Generally Māori continued to welcome Europeans for the benefits they brought, including access to goods, technology, ideas, and relationships. Māori also sought to maintain control over relationships with settlers and traders, and to ensure the newcomers abided with tikanga.

(To learn more, see our sources: Waitangi Tribunal, 2014; Walker, 2004).

He Whakaputanga – The Declaration of Independence

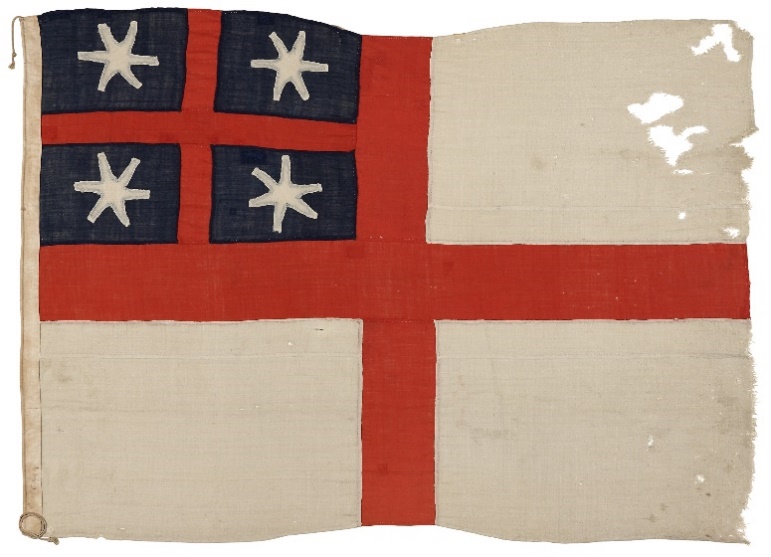

In 1831, in the context of unruly behaviour by Europeans who had settled predominantly in the Bay of Islands and Hokianga, leading rangatira petitioned the King of England to control British nationals and highlighted the importance of trade. Britain, too, wanted peace, trade, and control of its own disorderly subjects. In this context James Busby was appointed as British Resident, and in 1834 one of his initial acts was to meet with rangatira to select a flag.

On 28 October 1835 James Busby convened another significant meeting at Waitangi with 34 rangatira to sign He Whakaputanga o te Rangatiranga o Nu Tireni (He Whakaputanga), The Declaration of Independence. He Whakaputanga declared the independence of rangatira and asserted Aotearoa New Zealand as an independent state, while formalising and strengthening the relationship between Māori and Britain (Waitangi Tribunal, 2014). Importantly, He Whakaputanga was a declaration that Māori authority would endure, and it rejected any foreign authority over Māori people and territories (Walker, 2004). Furthermore, many hapū consider He Whakaputanga to be the founding document of Aotearoa New Zealand, and refer to it when exercising their independence and authority (Mutu, 2019). The context of He Whakaputanga is significant because it demonstrates Māori efforts and commitments to exercise independence and sovereignty from their earliest encounters with the British Crown.

Te Tiriti o Waitangi

He Whakaputanga and Te Tiriti o Waitangi (Te Tiriti) are both essential to the story of nationhood in Aotearoa New Zealand. Before we delve into Te Tiriti, there are important terms and details to be familiar with:

- There are two texts; Te Tiriti is the te reo Māori text and The Treaty of Waitangi (The Treaty) is the English text (these are sometimes referred to as the Māori version and the English version).

- The provisions are the specific terms of agreement, that is, what the text of Te Tiriti and The Treaty state.

- The principles are the current day consideration of the terms of agreement (there are several principles).

Te Tiriti is the founding document of Aotearoa New Zealand as a nation and representative of the relationship between the British Crown (the Government) and Māori. On 6 February 1840 at Waitangi, Te Tiriti was signed by over 40 rangatira and William Hobson as a representative of the Queen. In subsequent months more than 500 rangatira signed from around Aotearoa New Zealand (Mutu, 2011; Waitangi Tribunal, 2014).

Suffice to say there are considerable analyses and ongoing debates about the intentions, meanings, and effects of Te Tiriti and The Treaty. Here we want to highlight the significance of the provisions of Te Tiriti, because they have important implications for how contemporary health psychologists ought to think about health for Māori and Māori communities.

Professor Margaret Mutu is an expert in Te Tiriti and emphasises that in line with international law, it is Te Tiriti that is the official treaty. Furthermore, Te Tiriti was the document rangatira understood at the time and it was the document almost all rangatira signed (Mutu, 2011).

Professor Margaret Mutu on the provisions set out in Te Tiriti

On the part of the British, the Queen of England wished there to be peace and good order between her subjects and the Māori people, and to achieve that she needed to control her own Pākehā subjects living throughout the land already who were being lawless, as well as those who would be coming in the future. She asked the rangatira […] to allow her to do so using a mechanism called kāwanatanga. […] If the rangatira agreed to this she would respect and uphold their tino rangatiratanga and hence their mana, their ultimate and paramount power and authority over all their territories and people. She asked that in future the Queen or her agent be allowed to trade for use rights to lands of the hapū for prices agreed to by the agent and the owner of the land. Finally, in reciprocation for the care and protection provided by Māori to her Pākehā subjects, she likewise would care for and protect Māori and make available to Māori her own English culture and customs. (Mutu, 2011, p. 37).

What does Te Tiriti mean for hauora?

So far we have focused on the provisions, however we recognise that the principles are often at the forefront in discussions about Te Tiriti, especially in health contexts. While we detail the links between provisions, principles, and implementation of such, we emphasise that knowledge of the provisions is central to contemporary understandings about Te Tiriti (Te Atakura Educators, 2023).

- Kāwanatanga, meaning governance, is a provision of Article 1 of Te Tiriti. It is related to the current day principles of good governance and partnership. What this means is working together with Māori to improve health outcomes.

- Tino rangatiratanga is a provision of Article 2, and it refers to Māori maintaining independence over their lands and all their treasures. This is interpreted in current day principles as self-determination and active protection. This means Māori have control of Māori knowledges and self-determination over their health, across policy, delivery, content, and outcomes.

- Ngā tikanga katoa rite tahi, meaning all of the rights, is a provision of Article 3. It is related to the principles of participation and equity. In health contexts, this means that Māori have equitable access and opportunities to participate in health services and delivery at all levels.

- Te ritenga Māori, referring to Māori spiritual practices, is a provision of Article 4 (often described as the “Oral Article”). This is interpreted in current day principles and implementation as honouring Māori spiritual practices (Te Atakura Educators, 2023; New Zealand Psychologists’ Board, 2009).

Dr Moana Jackson (2020), lawyer and renowned Te Tiriti expert, summarised the intent of Te Tiriti as a vision of a prosperous partnership and peaceful co-existence between Māori and newcomers. It is our view that this vision also encompasses promoting hauora for Māori and the wellbeing of all people in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Want to know more detail about Te Tiriti and its relevance today?

- Read: For introductory and accessible coverage of the texts, you can read a summary by Professor Margaret Mutu.

Mutu, M. (2011). Constitutional intentions: The Treaty of Waitangi Texts. In M. Mulholland & V. Tawhai (Eds.), Weeping waters: The Treaty of Waitangi and constitutional change, (pp 16–33). Huia Publishers. - Watch: For for a contemporary perspective unpacking current political issues, watch another expert critical analyst and Te Tiriti educator, Veronica Tawhai:

Tawhai, V., Thompon, H., & Dewes, T. [RNZ] (2024, November 12). Hori on a hīkoi – Ngā porokāte: Episode 4: “Te Tiriti Party” (Part 1) – Veronica Tawhai. [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/OEx0yrFWP6k?si=Q_OG8FxebkyRt6QO

Colonisation – past and present

Despite the signing of Te Tiriti, the terms agreed to were not upheld by the Crown. In the subsequent decades, Māori were dispossessed of their lands and therefore their capacity to sustain themselves, both in practical and cultural terms (Walker, 2004). The history of Aotearoa New Zealand includes several events and Crown actions, including extensive land confiscation, warfare, and prohibition of te reo Māori in schools, which were extremely detrimental to the health and wellbeing of whānau, hapū, and iwi (Smith, 2021).

The assault on Māori health and wellbeing via legislation has been wide-reaching. Oftentimes discussions of colonisation frame it as an isolated event that occurred in some distant past. But, colonisation is present and ongoing; it continues in the laws and institutions in Aotearoa New Zealand, and its legacy impacts on the lived experiences of contemporary Māori (Reid et al., 2019). A defining feature of colonisation for Māori is the undermining of mana and rangatiratanga, or rather the denial of Māori independence and rights to be self-determining (Smith, 2021). Here we outline a selection of legislation and Crown or government actions since the signing of Te Tiriti to demonstrate the mechanisms by which colonisation operates.

Colonisation past and present in legislation and government actions

- Native Land Act 1862 created the Native Land Court to decide ownership of Māori lands and to transform communally owned land into individual titles. Land is a basis of identity for Māori and this law was extremely destructive to Māori wellbeing, with significant impacts culturally and economically (Walker, 2004).

- Native Schools Act 1867 established education for Māori, however in 1905 teachers were instructed to encourage only English be spoken in playgrounds. This led to the prohibition of te reo Māori within schools, which persisted over the subsequent 50 years and was at times enforced with corporal punishment. The suppression of language and identity has had a lasting harmful effect psychologically for Māori (Walker, 2004).

- Tohunga Suppression Act 1907 had a direct impact on Māori approaches to health. It undermined the legitimacy and ostracised mātauranga regarding healing, wairua, the environment, human behaviour, and arts (Durie, 2005).

- Foreshore and Seabed Act 2004 vested ownership of the foreshore and seabed with the Crown, limiting Māori ownership and control. A protest in opposition to the legislation travelled to Parliament. The concern for Māori was that tino rangatiratanga was being compromised, with many hapū and iwi viewing it as the largest seizure of land and resource since the nineteenth century (Spoonley, 2009; Walker 2004).

- Treaty Principles Bill 2024 was proposed to redefine the principles of Te Tiriti o Waitangi. The Waitangi Tribunal (2024) highlighted that the Bill breached tino rangatiratanga and recommended that it be abandoned, arguing it would hinder Māori access to justice and negatively impact social cohesion. There was significant opposition throughout Aotearoa New Zealand, including a protest to Parliament of over 42,000 people (RNZ, 2024). In April 2025, the bill was not supported at its second reading and it was terminated (New Zealand Parliament, 2025).

Our aim in giving attention to the historical and socio-political context of Aotearoa New Zealand has been to highlight events and associated narratives based in evidence. Many inaccurate retellings have proliferated over the years, perpetuating the colonial agenda by reinforcing mistaken ideas that Māori are inferior (Jackson, 2020). All of this relates to critical health psychology because historical events have long-lasting impacts on health status and colonisation affects contemporary health outcomes for Māori.

Māori health models and dimensions of hauora

The development of Māori health models grounded in Māori worldviews has provided culturally meaningful frameworks to engage in efforts towards optimal health and wellbeing for Māori. Broadly, Māori frameworks and initiatives that centre cultural understandings have contributed to significant gains in the health of Māori in the past 100 years, including improved life expectancy, lowered mortality rates, improved educational participation, and growth in te reo Māori acquisition (Durie, 2001; Tomlins-Jahnke & Mulholland, 2011).

In this section we summarise well-known and commonly used Māori health models. Then, in the subsequent section we explore core dimensions of hauora, with a focus on application. Consistent across Māori models of health and wellbeing are the themes of integration, balance, and relationality. Importantly, individual health is considered in the context of the environment and wider systems; there are no clear-cut distinctions between spiritual, psychological, physical, and collective dimensions (Durie, 2001). As we will cover, Māori health models readily use te reo Māori and metaphors derived from a Māori worldview. This provides ways of conceptualising hauora that are distinctly Māori, with solutions to uphold Māori health that are specific to Māori lived experiences.

Reflecting on your own positionality

Before we explore Māori health models, we need to revisit the ideas of positionality mentioned at the start of the chapter. We encourage you to consider your own positionality. We also bring to your attention the notion of cultural safety, a cornerstone of which is, “to produce a workforce of well educated, self-aware [practitioners] who are culturally safe to practice, as defined by the people they serve” (Ramsden, 2002 p. 94). Ongoing critical reflection of your own positionality and the ways it shapes your engagement with, and interpretation of, the world around you is essential. This necessitates cultural humility; to be open-minded, to develop awareness of your own positionality, and to learn from cultures different to your own (Christopher et al., 2014). Even with seemingly good intentions, using culturally based knowledges and health models in the absence of self-awareness and cultural humility can at best be improper, and at worst, harmful.

A starting point for reflection on your own positionality if you live in Aotearoa New Zealand

- What are my own cultural identities? How do these locate or position me in Aotearoa New Zealand?

- How am I connected to Māori communities?

- What is my understanding of Māori knowledges?

- What and whose interests are served by my engaging with Māori knowledges and Māori health models?

- You can see Fraser and Walker Chapter 3.1 to further explore these ideas in terms of reflexivity.

Te Whare Tapa Whā

A seminal Māori health model, Te Whare Tapa Whā, frames wellbeing as achieved through balance across four domains: te taha tinana, referring to physical wellbeing; te taha hinengaro, mental and emotional wellbeing; te taha whānau, representing family and social wellbeing; and te taha wairua, spiritual wellbeing (Durie, 1985, 2001). The whare is also conceptualised as sitting on the whenua, representing the importance of Māori connection to ancestral lands and the natural environment. Wellbeing is flourishing when all four domains are cared for and in balance, whereas illness or dysfunction develop when one or more of the domains are compromised. Te Whare Tapa Whā has been established and endorsed across psychology and health disciplines, reinforcing the importance of a holistic understanding and approach to health for Māori.

Te Wheke

Another well-recognised Māori model of health, Te Wheke, affirms that individual wellbeing is inseparable from whānau wellbeing (Pere, 1997). Represented as an octopus, the head symbolises whānau and the eyes represent waiora, which in the model is understood as the overall wellbeing of whānau. Each of the eight tentacles represent a dimension fundamental to Maōri wellbeing, including those encompassed in Te Whare Tapa Whā (wairuatanga, hinengaro, tinana, and whanaungatanga) as well as a further four dimensions: mauri, referring to life essence; mana ake as unique identity; hā a koro mā, a kui mā, representing breath of life from ancestors; and whatumanawa as healthy expression of emotions.

Meihana Model

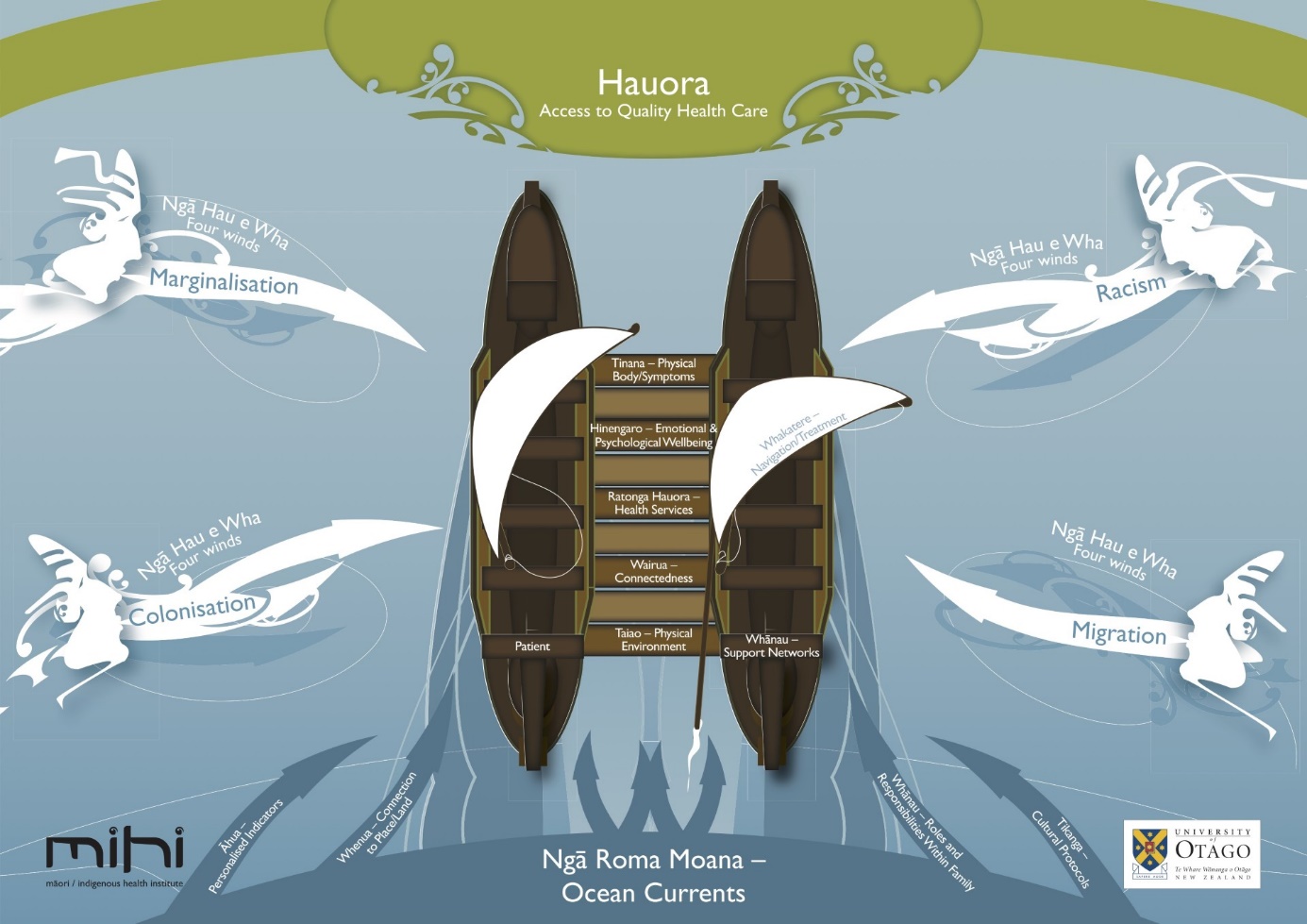

The Meihana Model provides a practical guide for clinical assessment and treatment and is represented as a waka hourua traversing the ocean (Pitama et al., 2007, 2017). The Meihana Model places whānau at the centre, alongside the individual, and similarly includes the four core dimensions of Te Whare Tapa Whā. It also extends to account for the historical and social context of Aotearoa New Zealand, represented as ngā hau e whā, the four winds, and in so doing recognises the ongoing impact of colonisation, migration, marginalisation, and racism for whānau. In addition, the Meihana Model identifies components from te ao Māori that may influence a person and their whānau. These are depicted as ngā roma moana, ocean currents, and comprise: āhua, referring to personalised indicators; tikanga; whānau, specifically roles and responsibilities within families; and whenua, representing spiritual and ancestral connections to land.

Te Pae Māhutonga

The fourth model we share uses a star constellation and brings together elements of health promotion. Te Pae Māhutonga represents charting a course towards Māori health and wellbeing (Durie, 1999). It is a significant constellation in ocean navigation and voyaging, aiding the traditional migrations to Aotearoa New Zealand from the Pacific. The constellation consists of four central stars that symbolise the key tasks of health promotion: mauriora, reflecting access to te ao Māori; waiora, representing environmental protection; toiora, denoting healthy lifestyles; and te oranga, indicating participation in society. There are two additional pointer stars, which are named in the model as ngā manukura, referring to leadership, and te mana whakahaere, as autonomy. Just as Te Pae Māhutonga as a constellation has served as a guide for successive generations, likewise Te Pae Māhutonga as a model of health promotion provides a map to integrate elements of health promotion as related to Māori health.

How are dimensions of hauora applied?

We use the term “dimensions of hauora” to encompass what Māori health models describe as taha, domains, tasks, and so on. Although we discuss the dimensions of hauora as distinct concepts, bear in mind the interdependent nature of Māori worldviews. All of these dimensions are connected, fluid, and often overlapping, with no clear lines separating one from another. Linking back to our discussion of historical and socio-political contexts, it is also important to acknowledge the wider contexts that impact on understandings and practices related to the application of Māori knowledges and Māori health models.

Drawing on examples from research and professional practice in psychology, mental health, and broader literature pertaining to hauora and Māori wellbeing, we demonstrate the implications of Māori health models and dimensions of hauora for critical health psychology. We begin by discussing the four taha within Te Whare Tapa Whā, which are mirrored in many Māori health models, and we then explore additional dimensions of hauora that have particular relevance in contemporary settings.

Wairua

We begin with wairua, because this is a central to a Māori way of being and therefore foundational to hauora. Reverend Māori Marsden, who was a tohunga regarded for his expertise on Māori divinity and an ordained Anglican minister, describes wairua as the ultimate reality of existence for Māori (Marsden, 1992). Similarly, from Māori psychological perpsectives wairua is described as the fundamental, boundless, and connective aspect of Māori life and ways of being (Valentine, 2009; Valentine et al., 2017). Wairua is a connection to that which is sacred, which is all-encompassing from a Māori standpoint (Brittain, 2022). Therefore wairua can be understood as spirituality, the unseen, divine, connectedness, and is also much more; it permeates Māori views and experiences of the world. Given this, wairua is an essential dimension to hauora for Māori.

Māori spiritual healers’ perspectives on healing practices, health, and wellbeing

Mark and Lyons (2010, 2014) highlight the ways Māori spiritual healers conceptualised interconnections between mind, body, and spirit. Wairua and spirituality were identified as central to healing processes, and for healers encompassed sensory perception and communication with spiritual sources. The significance of whānau and whenua to wellbeing was also emphasised. These understandings and research findings support the use of multiple and holistic approaches to improve health for Māori and Indigenous peoples.

Whānau

Whānau is commonly translated as family, although the modern use of whānau to refer to the parent-child family unit is a contemporary development. In te reo Māori, when whānau is used as a noun it refers to children of the same parents, a family group, extended family, and can be applied to friends. Whānau can also be a verb, meaning to give birth or to be born. Whānau traditionally were the basic social unit, typically comprising an extended family unit spanning three generations (Walker, 2004). Throughout Māori models of health, whānau and collective wellbeing are prioritised, and working with whānau in health psychology settings can enhance hauora for whānau and individuals alike.

Professional practice exemplars discussed in Te Manu Kai i te Mātauranga: Indigenous psychology in Aotearoa New Zealand (Waitoki & Levy, 2016)

Using a case study format focusing on the story of a Māori woman, Ripeka, and her whānau, including her partner, young children, and also her grandparents, this edited book shares insights from several Māori psychologists about how they would engage with Ripeka and her whānau. Drawing on Māori worldviews and mātauranga, exemplars of therapeutic and healing approaches are provided for working with whānau Māori. These include the use of pūrākau and narratives to work toward whānau healing (Cherrington, 2016); addressing and preventing whānau violence (Cooper & Rickard, 2016); and working alongside mothers and infants in a culturally centred way to support whānau wellbeing (Cargo, 2016). Whānau health and wellbeing is foregrounded in Māori approaches. Engaging with an individual who is experiencing distress and difficulties at a minimum necessitates an appreciation for whānau, and ideally entails whānau-centred practice. For example, one approach Cherrington proposes as a path to whānau healing is to retell the pūrākau of Ranginui and Papatūānuku. She explains, addressing Ripeka and her whānau:

Why do I want to talk to you about Ranginui and Papatūānuku and all their kids? Because this whānau is a part of our identity as Māori. This whānau was not perfect, but they were known as atua, as gods. They had their own problems to deal with. They were a whānau struggling to cope with a separation. Each child had a different reaction. And they were not perfect by any means. All of these family members had strengths and weaknesses. (Cherrington, 2016, p. 117).

Hinengaro

The next dimension of hauora is hinengaro. Of interest to psychology in general, hinengaro encompasses the mind, thoughts, emotions, and intellect (Durie, 2001). Rangimarie Pere, who developed Te Wheke and is regarded as a tohunga, conceptualises hinengaro as comprising the conscious and subconscious aspects of mind (Pere, 1997). Furthermore, Māori worldviews maintain that thought, awareness, and understanding are not solely activities of the mind, but are deeply connected with bodily or embodied experiences (Marsden, 2003). For example, ngākau represents the heart and seat of emotions, and is attuned to hinengaro and wairua. Similarly ate referring to the liver, and puku to the stomach are also regarded as emotional centres within the body (Smith, 2008).

Collaborative approach to mental health practice using Māori healing practices and mainstream psychiatry (NiaNia et al., 2017)

In the book Collaborative and Indigenous Mental Health Therapy a series of case narratives are presented detailing the work of Wiremu NiaNia, Māori healing practitioner, and Alistair Bush, psychiatrist. They model a collaborative approach to mental health practice, drawing together Māori healing practices and mainstream psychiatry. In one case narrative, “Into the World of Light” (NiaNia et al., 2017, pp. 103–140), the pūrākau of creation is integrated in the therapeutic approach, with a focus on Hine-tītama and her transformation to Hine-nui-te-pō. Hinengaro is symbolic of pain and loss, portrayed as affecting the depths of the mind and emotional experience. As one component of treatment and therapy, the young person in the case narrative, Tangi, who is an artist, is encouraged to connect with this pūrākau in her artwork to shape a narrative that shifts from darkness and obscurity, to light. Tangi describes engaging with art as key to working through her experiences of depression and as a way of relating to wairua. She also reflects on her focus on Hine-tītama and Hine-nui-te-pō in her art as symbolising the beginning of her recovery towards wellbeing.

Tinana

Tinana refers to the physical body and as a dimension of hauora caring for physical wellbeing can include; regular exercise, eating a balanced and nutritious diet, and healthy sleep habits. Equally it can entail understanding and managing chronic illnesses and health conditions, as well as reducing harms associated with substance use. Physical wellbeing is often framed in terms of individual health behaviours and lifestyle choices. Individuals, particularly Māori, are blamed for making poor choices for their health in ways that disregard context, and instead ethnic or cultural identities are misconstrued as risk factors. Ethnicity is certainly important to consider for physical wellbeing, however, a more constructive perspective is to consider Indigeneity as an indication of exposure to risk factors (Huria et al., 2019).

A widely circulated framing of health connects physical health to lifestyle choices and an individual’s responsibility to participate in recognised health behaviours, such as eating a nutritious diet. This individualism disregards the social determinants of health, the circumstances and environment of people’s lives that determine their health. Social determinants of health for Māori contribute to severe inequities across all levels of health (Reid et al., 2019). (For further discussion of dominant discourses that construct health as an individual responsibility, see Riley et al. Chapter 1.4.)

Evidence of Kaupapa Māori health interventions

Rolleston et al. (2019) reviewed Kaupapa Māori health interventions used in the prevention or management of a chronic condition. They identified 13 interventions, with the majority focused on lifestyle change and health promotion. Interventions included exercise and lifestyle management for the prevention of cardiovascular disease, health promotion and community education for diabetes prevention, and health literacy resources for gout. Importantly, all of the interventions were reported as successful when assessed against their stated aims. However, a key issue noted was the visibility of evidence for Kaupapa Māori health interventions for the prevention and management of chronic conditions. There is a strong argument for culturally centred health interventions that draw on mātauranga and use Kaupapa Māori approaches.

Furthermore, the wellbeing of tinana is closely linked with wairua, hinengaro, and whānau health. As we highlighted earlier, the dimensions of hauora are interconnected. At times, what may present as a physical or mental illness from a Western medical perspective could have a spiritual basis, or reflect disharmony in whānau circumstances. From a Māori perspective, while issues may manifest physically, explanations may be spiritual or non-physical, therefore necessitating different treatment or healing practices.

The connections between dimensions of hauora

Watch: Professor Sir Mason Durie tells a story of a young girl admitted to hospital with what appeared to Western medicine to be a virus, but a Māori worldview deduced different causes and different solutions.

Ministry of Health – Manatū Hauora. (2014, July 16). He korowai oranga: Māori health strategy launch – Sir Mason Durie. [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/ypKwMUWSUt4?si=MRwFNVIodR5Eb6Zz

Culture and te reo Māori

Access to culture and te reo Māori is well established as foundational to Māori wellbeing. A positive sense of Māori identity cultivated through cultural and social connection provides a strong base for wellbeing. Māori identity is also considered to be a protective factor for Māori health, as it can be a source of grounding that enables a person respond to challenges in a resilient manner (Durie, 2001).

As discussed earlier, Te Kōhanga Reo and Kura Kaupapa Māori were established as alternative forms of education for Māori in the 1980s, in the context of revitalisation efforts for te reo Māori and recognition of Te Tiriti. Te reo Māori education has provided a crucial pathway for Māori to be connected to Māori worldviews and knowledges and through this, to strengthen cultural identities (Durie, 2003). Māori culture and te reo Māori are also embraced and celebrated in kapa haka, a form of Māori performing arts that is significant to Māori culture and has become a unique part of national identity in Aotearoa New Zealand. Notably, Te Matatini is an acclaimed national Māori performing arts festival held every two years, providing an incentive for individuals and communities to increase their knowledge and understanding of Māori culture and te reo Māori (Durie, 2017).

Ngā hua a Tāne-rore: The benefits of kapa haka (Pihama et al., 2014)

Pihama et al. (2014) assert there are many benefits of kapa haka as a gateway to wellbeing for whānau and communities.

- Kapa haka facilitates whanaungatanga. Through connectedness, shared experiences, and collective support it offers opportunities to strengthen whānau and unite communities.

- It is a vehicle to develop holistic wellbeing. Physical health and fitness are improved collectively, while mental and emotional wellbeing are supported through relationships and experiences of pride.

- Mātauranga, Māori traditions and histories, and te reo Māori are upheld and revived through kapa haka.

- Kapa haka provides opportunities for Māori who may not be engaged with their marae, hapū, and iwi to access and connect to Māori culture.

There are wide-reaching benefits, from positive health outcomes, to educational opportunities, social cohesion, and also cultural development. Kapa haka has the power to effect wellbeing and to positively transform the lives of whānau, individuals, and communities.

Whenua and te taiao

As a final dimension of hauora, whenua and te taiao are important for hauora in multiple ways. Māori worldviews maintain that people are connected to the natural world and land through whakapapa. Connectedness to whenua and te taiao is essential to cultural identity and belonging. This is reflected in key te reo Māori terms that depict Māori relationships with the land:

- Whenua refers to land and it is also the term for placenta. These dual meanings are similar in reflecting a source of sustenance.

- Tangata whenua, meaning people of the land, is used to describe Māori as Indigenous in Aotearoa New Zealand.

- Tūrangawaewae describes a standing place and belonging granted through whakapapa. It is usually used to refer to ancestral lands where one has rights of belonging.

- Ūkaipō refers to origins or homelands. It also has a dual meaning, describing a mother as a source of sustenance.

Whenua is also closely connected to wairua and whakapapa, therefore efforts toward hauora for Māori must acknowledge relationships with the wider environment (Mark & Lyons, 2010; NiaNia et al., 2017). The significance of te taiao is denoted in Māori creation narratives. Māori view the lands, sky, winds, seas, waterways, forests, and the natural environment as atua and as tīpuna. Given this relationship, a Māori worldview also maintains that Māori have obligations and responsibilities to te taiao. The concept of kaitiakitanga encompasses the responsibilities of guardianship and caretaking of the natural environment, to protect and preserve te taiao for future generations (Marsden, 2003). Māori wellbeing across the dimensions of hauora is understood as deeply intertwined with, and dependent upon, the state of te taiao. The impacts of climate change and widespread degradation of the natural environment in the contemporary context therefore pose significant issues for Māori.

Climate change and the impacts for Māori wellbeing

Jones (2019) highlights that climate change is contributing to a disruption of Māori and Indigenous peoples’ relationships with lands, through environmental effects such as sea level rise and coastal erosion. Given that whenua and te taiao are central to hauora for Māori, this has drastic potential consequences. Many communities face displacement from their lands, and climate change may exacerbate existing social and health inequities for Māori and Indigenous peoples around the globe. Climate action from a Māori perspective is underpinned by the spiritual and relational significance of whenua and te taiao to Māori lived experiences.

The Ministry of Health (2024) in Aotearoa New Zealand recognises the significance of climate change to hauora for Māori and adaptation efforts from Māori communities in the National Health Adaptation Plan 2024-2027. Hapū and iwi led responses to the extreme weather during Cyclone Gabrielle in 2023 were critical in the immediate aftermath and recovery efforts. Many marae and whānau supported the civil defence response by becoming emergency centres, housing displaced people, distributing food and supplies, and coordinatung these efforts. Furthermore, whānau, hapū, and iwi in affected areas continue to support communities to recover.

In discussing the dimensions of hauora and examples of application we have endeavoured to demonstrate the ways these dimensions and Māori models of health can be translated from conceptual to practical. An expanding body of Māori research and approaches to wellbeing employs knowledges and practices originating in te ao Māori. Across the dimensions of wairua, whānau, hinengaro, tinana, culture and te reo Māori, as well as whenua and te taiao, there are many avenues for Māori understandings to enrich health psychology.

In pracitical terms, appropriate integration of tikanga, use of karakia and te reo Māori, active whānau involvement, use of whanaungatanga to develop relationships, and facilitating access to rongoā are experienced positively by Māori accessing health services (Pere, 2006; Waitoki et al., 2015). Such efforts underpin models of practice within Māori health services and are means by which the principles of Māori models of health are incorporated to enhance outcomes and hauora for Māori.

Conclusion – hauora in a changing world

We conclude by emphasising that contexts influence health experiences and outcomes. Hauora for Māori exists in a changing health landscape, with implications for contemporary health psychology. The contexts we live in are constantly evolving, therefore our thinking and practices must also continually develop and adapt. The challenge for critical health psychology in Aotearoa New Zealand is to not only be aware of contexts and structures, but to respond constructively, with a commitment to benefitting hauora and Māori communities.

The critical health psychology pou have emerged throughout this chapter. The pou of valuing theoretical and conceptual thinking was relevant to our discussion of Māori worldviews, knowledges, and understandings of health and wellbeing. In reviewing the historical and socio-political context in Aotearoa New Zealand and Te Tiriti, the pou of challenging taken–for–granted understandings and paying attention to issues of power and equity were important. Māori models of health, dimensions of hauora, and links to application and practice offer exemplars of the pou of moving beyond individualistic psychology and considering knowledge as produced in context.

We hope this chapter offers conceptual, historical, and practical foundations to rethink Māori and Indigenous health and wellbeing. Our coverage of Māori knowledges and understandings is intended to ignite thought and reconceptualisation of ideas within health psychology. To this point, Reid et al. (2010) implore Māori and Indigenous peoples alike regarding the importance of creative and critical thought for the future:

Indigenous knowledges are not solely ancient wisdoms but necessarily include processes for the creation of new Indigenous knowledge that have the potential to contribute to well-being of all peoples, our environment and our planet. […] This Indigenist approach to research and science holds important answers for the critical questions we currently face in collective well-being.

Māori working in health psychology have a significant responsibility, to both draw on existing Māori knowledges and to also create Māori knowledges to contribute to hauora. The health and wellbeing of Māori is a pressing issue that must be informed and led by Māori scholars and practitioners, and Māori worldviews and practices. The task for all involved in health psychology in Aotearoa New Zealand begins with cultural humility, to be aware of positionality, to be open-minded, and to learn. These issues are equally important for all who study, teach, research, and engage with health psychology in Aotearoa New Zealand. There is abundant potential for Māori knowledges and practices to enrich and expand health psychology, so that hauora for Māori can flourish.

Knowledge Check

Want to know more?

Listen: Treaty Talks – RNZ https://www.rnz.co.nz/video/treaty-talks

Read: Waitoki, W., & Levy, M. (2016). Te manu kai i te mātauranga: Indigenous psychology in Aotearoa/New Zealand. New Zealand Psychological Society.

Watch: Dr Moana Jackson, constitutional lawyer and Te Tiriti expert, discuss the meaning and effect of Te Tiriti.

He Tohu. (2017, June 8). Moana Jackson – He Tohu interview. [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/GDM-Ct21N4I?si=t4KZd13rsC68UvR6

References

Barlow, C. (1991). Tikanga whakaaro: Key concepts in Māori culture. Oxford University Press.

Bishop, R. (1998). Freeing ourselves from neo-colonial domination in research: A Māori approach to creating knowledge. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 11(2), 199–219. https://doi.org/10.1080/095183998236674

Brittain, E. (2022). Ko wai, ko wairua: Narratives of wairua and wellbeing. [Doctoral dissertation]. Massey University. http://hdl.handle.net/10179/17665

Cargo, T. (2016). Kaihau waiū: Attributes gained through mother’s milk: The importance of our very first relationship. In W. Waitoki & M. Levy (Eds.), Te manu kai i te mātauranga: Indigenous psychology in Aotearoa/New Zealand (pp. 243–269). New Zealand Psychological Society.

Cherrington, L. (2016). Re: “I just want to heal my family”. In W. Waitoki & M. Levy (Eds.), Te manu kai i te mātauranga: Indigenous psychology in Aotearoa/New Zealand (pp. 115–123). New Zealand Psychological Society.

Christopher, J. C., Wendt, D. C., Marecek, J., & Goodman, D. M. (2014). Critical cultural awareness: Contributions to a globalizing psychology. American Psychologist, 69(7), 645–655. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/a0036851

Cooper, E. & Rickard, S. (2016). Healing whānau violence: A love story. In W. Waitoki & M. Levy (Eds.), Te manu kai i te mātauranga: Indigenous psychology in Aotearoa/New Zealand (pp. 99–114). New Zealand Psychological Society.

Durie, M. (1985). A Māori perspective of health. Social Science & Medicine, 20(5), 483–486. https://doi.org/10.1016/0277-9536(85)90363-6

Durie, M. (1999). Te Pae Māhutonga: A model for Māori health promotion. Health Promotion Forum of New Zealand Newsletter. https://www.cph.co.nz/wp-content/uploads/TePaeMahutonga.pdf [PDF]

Durie, M. (2001). Mauri ora: The dynamics of Māori health. Oxford University Press.

Durie, M. (2005). Whaiora: Māori health development. Oxford University Press.

Henare, M. (1988). Ngā tikanga me ngā ritenga o Te Ao Māori: Standards and foundations of Māori society. In The April report: Report of the Royal Commission on Social Policy. Volume 3, part 1: Future directions, associated papers. The Royal Commission on Social Policy. https://ndhadeliver.natlib.govt.nz/delivery/DeliveryManagerServlet?dps_pid=IE17401282

Henry, E. & Pene, H. (2001). Kaupapa Māori research: Locating indigenous ontology, epistemology and methodology in the academy. Organization, 8(2), 234–242. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508401082009

He Tohu. (2017, June 8). Moana Jackson – He Tohu interview. [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/GDM-Ct21N4I?si=t4KZd13rsC68UvR6

Huria, T., Palmer, S. C., Pitama, S., Beckert, L., Lacey, C., Ewen, S., & Smith, L. T. (2019). Consolidated criteria for strengthening reporting of health research involving indigenous peoples: The CONSIDER statement. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 19, 173. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-019-0815-8

Irwin, K. (1992). Māori research methods and processes: An exploration and discussion [Paper presentation]. New Zealand Association for Research in Education / Australian Association for Research in Education Conference, Geelong, Australia.

Jackson, M. (2020). Where to next? Decolonisation and the stories in the land. In R. Kiddle (Ed.), Imagining decolonisation (pp. 133–155). BWB Texts.

Jones, R. (2019). Climate change and Indigenous health promotion. Global Health Promotion. 26(3), 73–81. https://doi.org/10.1177/1757975919829713

Koea, J., Mark, G., Kerridge, D., & Boulton, A. (2024). Te Matahouroa: A feasibility trial combining rongoā Māori and Western medicine in a surgical outpatient setting. New Zealand Medical Journal, 137(1597), 25–35. https://nzmj.org.nz/media/pages/journal/vol-137-no-1597/b20d3c915f-1718768004/nzmjv137i1597_21june2024.pdf#page=25

Lee-Morgan, J. B. J. (2019). Pūrākau from the inside-out: Regenerating stories for cultural sustainability. In J. Archibald, J. B. J. Lee-Morgan, & J. D. Santolo (Eds.), Decolonizing research: Indigenous storywork as methodology (pp. 151–166). Zed Books.

Mark, T. & Lyons, A. (2010). Māori healers’ views on wellbeing: The importance of mind, body, spirit, family and land. Social Science & Medicine, 70(11), 1756–1764. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.02.001

Marsden, M. (1992). God, man and universe: A Māori view. In M. King (Ed.), Te ao hurihuri: Aspects of Māoritanga (pp. 117–137). Reed Publishing (NZ).

Marsden, M. (2003). Kaitiakitanga: A definitive introduction to the holistic worldview of the Māori. In T. A. C. Royal (Ed.), The woven universe: Selected writings of Rev. Māori Marsden (pp. 54–72). The Estate of Rev. Māori Marsden.

Mead, H. M. (2016). Tikanga Māori: Living by Māori values (Rev. ed.). Huia Publishers.

Ministry of Health. (2023). Pae Tū: Hauora Māori strategy. https://www.health.govt.nz/system/files/2023-07/hp8748-pae-tu-hauora-maori-strategy.pdf [PDF]

Ministry of Health. (2024). Health National Adaptation Plan 2024–2027. https://www.health.govt.nz/system/files/2024-10/Health%20National%20Adaptation%20Plan%202024-2027_0.pdf [PDF]

Ministry of Health – Manatū Hauora. (2014, July 16). He korowai oranga: Māori health strategy launch – Sir Mason Durie [Video]. https://youtu.be/ypKwMUWSUt4?si=hBVsfc6IKWnBP9_I

Mutu, M. (2011). Constitutional intentions: The Treaty of Waitangi Texts. In M. Mulholland & V. Tawhai (Eds.), Weeping waters: The Treaty of Waitangi and constitutional change (pp 16–33). Huia Publishers.

Mutu, M. (2019). ‘To honour the treaty, we must first settle colonisation’ (Moana Jackson 2015): The long road from colonial devastation to balance, peace and harmony. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand, 49(S1), 4–18. https://doi.org/10.1080/03036758.2019.1669670

Nepe, T. M. (1991). E hao nei e tēnei reanga: Te toi huarewa tipuna: Kaupapa Māori: An educational intervention system [Masters thesis, University of Auckland]. ResearchSpace. https://hdl.handle.net/2292/3066

New Zealand Psychologists Board. (2009). Guidelines for cultural safety: The Treaty of Waitangi and Māori health and wellbeing in education and psychological practice. New Zealand Psychologists Board. https://psychologistsboard.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/GUIDELINES-FOR-CULTURAL-SAFETY-130710.pdf [PDF]

NiaNia, W., Bush, A., & Epston, D. (2017). Collaborative and Indigenous mental health therapy: Tātaihono – Stories of Māori healing and psychiatry. Taylor & Francis.

Paringatai, K. [TEDx Talks] (2015, November 11). My whakapapa saved my life. [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/C4DkH_O9uME?si=CQWIWppLKvkd3Jag

Pere, R. (1997). Te wheke: A celebration of infinite wisdom. Ao Ako Global Learning New Zealand.

Pihama, L. (2010). Kaupapa Māori theory: Transforming theory in Aotearoa. He Pukenga Kōrero: A Journal of Māori Studies, Raumati (Summer), 9(2), 5–14. https://moodle.unitec.ac.nz/pluginfile.php/490153/mod_resource/content/2/Pihama%20Kaupapa%20Rangahau%20-%20A%20Reader_2nd%20Edition%202015.pdf#page=7

Pihama, L., & Smith, L. T. (2023). Ora: Healing ourselves: Indigenous knowledge, healing and wellbeing. Huia.

Pihama, L., Tipene, J., & Skipper, H. (2014). Ngā Hua a Tāne Rore: The Benefits of Kapa Haka. (Report). Manatū Taonga – Ministry of Culture & Heritage. https://researchcommons.waikato.ac.nz/entities/publication/a5e08e2f-c525-4903-b440-2233ac77997f

Pitama, S., Robertson, P., Cram, F., Gillies, M., Huria, T., & Dallas-Katoa, W. (2007). Meihana Model: A clinical assessment framework. New Zealand Journal of Psychology, 36(3), 118–125.

Pitama, S. G., Bennett, S. T., Waitoki, W., Haitana, T. N., Valentine, H., Pahina, J., Taylor, J. E., Tassell-Matamua, N., Rowe, L., Beckert, L., Palmer, S. C., Huria, T. M., Lacey, C. J., & McLachlan, A. (2017). A proposed Hauora Māori clinical guide for psychologists: Using the hui process and Meihana model in clinical assessment and formulation. New Zealand Journal of Psychology, 46(3), 7–19. https://researchcommons.waikato.ac.nz/server/api/core/bitstreams/a4fe4ba3-4508-4bc6-80b2-a7f69472962e/content

Prentice, K. [Māori Minds] (2022, June 15). The ontology of whanaungatanga. [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/16dF6WyuquM?si=a2T2JvhxM_YrShyO

Ramsden, I. (2002). Cultural safety and nursing education in Aotearoa and Te Waipounamu [Doctoral dissertation, Victoria University of Wellington]. Open Access Te Herenga Waka—Victoria University of Wellington. https://www.iue.net.nz/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/RAMSDEN-I-Cultural-Safety_Full.pdf [PDF]

Reid, P., Cormack, D., & Paine, S. J. (2019). Colonial histories, racism and health – The experience of Māori and Indigenous peoples. Public Health, 172, 119–124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.puhe.2019.03.027

RNZ [Radio New Zealand]. (2024, November 19). 42,000 join as Treaty Principles Bill hīkoi reaches parliament. https://www.rnz.co.nz/news/political/534140/42-000-join-as-treaty-principles-bill-hikoi-reaches-parliament

Rolleston, A. K., Cassim, S., Kidd, J., Lawrenson, R., Keenan, R., & Hokowhitu, R. (2020). Seeing the unseen: Evidence of Kaupapa Māori health interventions. AlterNative, 16(2), 129–136. https://doi.org/10.1177/1177180120919166

Royal Society Te Apārangi. (2023). Prime Minister’s Science Prizes Aotearoa New Zealand: 2023 Winner of Te Puiaki Pūtaiao Matua a te Pirimia: The science prize. https://pmscienceprizes.org.nz/2023-winner-of-te-puiaki-putaiao-matua-a-te-pirimia-the-science-prize/

Royal, T. A. C. (2005). Māori creation traditions. Te Ara: The Encyclopedia of New Zealand. https://teara.govt.nz/en/maori-creation-traditions

Royal, T. A. C. (2012). Politics and knowledge: Kaupapa Māori and mātauranga Māori. New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies Te Hautaki Mātai Mātauranga o Aotearoa, 47(2), 30–37.

Smith, G. H. (2017). Kaupapa Māori theory: Indigenous transforming of education. In T. K. Hoskins & A. Jones (Eds.), Critical conversations in Kaupapa Māori (pp. 70–81). Huia.

Smith, L. T. (2021). Decolonizing methodologies: Research and indigenous peoples (3rd ed.). Zed Books.

Smith, T. (2008). Indigenous knowledge in the Pacific: Knowing and the ngākau. Democracy & Education, 17(2), 10–14.

Spoonley, P. (2009). Mata toa: The life and times of Ranginui Walker. Penguin Books.

Stewart, G. T. (2021). Defending science from what? Educational Philosophy and Theory, 56(6), 509–512. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2021.1966415

Tawhai, V., & Rickard, K. [RNZ]. (2025, February 3). Treaty Talks – Episode 8: Dr. Veronica Tawhai. [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/wPhJAoVXFmA?si=FD1ntf0ONgStrMge

Tawhai, V., Thompon, H., & Dewes, T. [RNZ] (2024, November 12). Hori on a hīkoi – Ngā porokāte: Episode 4: “Te Tiriti Party” (Part 1) – Veronica Tawhai. [Video]. YouTube. https://youtu.be/OEx0yrFWP6k?si=Q_OG8FxebkyRt6QO

Tomlins-Jahnke, H., & Mulholland, M. (2011). Mana tangata: Politics of empowerment. Huia

Valentine, H. (2009). Kia ngāwari ki te awatea: The relationship between wairua and Māori well-being: A psychological perspective [Doctoral dissertation, Massey University]. Massey Research Online. http://hdl.handle.net/10179/1224

Valentine, H., Tassell-Mataamua, N., & Flett, R. (2017). Whakairia ki runga: The many dimensions of wairua. New Zealand Journal of Psychology, 46(3), 64–71.

Waitangi Tribunal. (2014). He Whakaputanga me Te Tiriti: The Declaration and The Treaty: The report on stage 1 of the Te Paparahi o Te Raki Inquiry. https://www.waitangitribunal.govt.nz/inquiries/district-inquiries/te-paparahi-o-te-raki-northland/

Waitangi Tribunal. (2024). Tribunal releases report on Treaty Principles Bill. https://waitangitribunal.govt.nz/en/news-2/all-articles/news/tribunal-releases-report-on-treaty-principles-bill

Waitoki, W., & Levy, M. (2016). Te manu kai i te mātauranga: Indigenous psychology in Aotearoa/New Zealand. New Zealand Psychological Society.

Walker, R. (1992). The relevance of Māori myth and tradition. In M. King (Ed.), Te ao hurihuri: Aspects of Māoritanga (pp. 170–182). Reed Publishing (NZ).

Walker, R. (2004). Ka whawhai tonu mātou: Struggle without end (Rev. ed.). Penguin Books.

A term used to acknowledge and respect Māori language and identity, and is thus a more inclusive term for the country.

Te reo Māori text of the treaty signed in 1840 between the British Crown and Māori, referred to as the founding document of Aotearoa New Zealand as a nation. Discussed in detail in Chapter 1.1.

A kinship group or subtribe, comprised of a number of whānau (family) and sharing a common ancestor; section of an iwi (tribe) and the primary political unit in traditional Māori society.

Extended Māori kinship group, tribe, nation; a large group of people descended from a common ancestor and associated with a distinct territory, usually comprised of a number of hapū (subtribes).

Family, extended family.

A gathering place for Māori made up of a communal complex of buildings and grounds belonging to a particular hapū (sub-tribe). The marae includes the courtyard, wharenui (meeting house), wharekai (dining hall), and sometimes other grounds and buildings.

Abbreviation of Ranginui; Sky, Sky Father.

Earth, ground, also an abbreviation of Papatūānuku.

The Māori language.

A Māori word that refers to the breath of life and spirit; a physical sense of wellbeing for an individual, and integrated with, and dependent upon, collective qualities. References: Henare, M. (1988). Ngā tikanga me ngā ritenga o te ao Māori: Standards and foundations of Māori society. In The April report: Report of the Royal Commission on Social Policy. Volume 3, Part 1: Future directions, associated papers. The Royal Commission on Social Policy. https://ndhadeliver.natlib.govt.nz/delivery/DeliveryManagerServlet?dps_pid=IE17401282; Pihama, L., & Smith, L. T. (2023). Ora: Healing ourselves: Indigenous knowledge, healing and wellbeing. Huia.

Relationships, sense of connectedness; refers to relationship and kinship; it highlights connections between the natural world, gods or deities, ancestors, and humankind and encompasses a collective interdependence (Henry & Pene, 2001). Reference: Henry, E., & Pene, H. (2001). Kaupapa Māori research: Locating indigenous ontology, epistemology and methodology in the academy. Organization, 8(2), 234–242. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350508401082009

Refers to the life-giving essence, the spark and vitality of life that binds the spiritual and physical (Barlow, 1991; Mead, 2016). References: Barlow, C. (1991). Tikanga whakaaro: Key concepts in Māori culture. Oxford University Press; Mead, H. (2016). Tikanga Māori: Living by Māori values. Huia.

Refers to total wellbeing and strength of spirit, denoting flowing and life-sustaining waters (Pere, 1997). Reference: Pere, R. (1997). Te wheke: A celebration of infinite wisdom. Ao Ako Global Learning New Zealand.

Describes family and collective wellbeing; a term promoted in contemporary Māori health policy.

The Māori world, Māori worldviews.

Refers to the most distant phase in time, the beginning of the universe from a Māori worldview; meaning the source of all life, the nothingness, and the void.

Refers to the second phase in time in the origins of the universe from a Māori worldview within which only atua (gods) existed; meaning darkness, and the night.

Refers to the third phase in time in the origins of the universe from a Māori worldview, within which humans exist; meaning the world of light.

Referring to Māori gods, deities, supernatural beings, or ancestors with continuing influence.

Ancestors.

Earth, Earth Mother.

Sky, Sky Father.

An atua or god in a Māori worldview; offspring to Papatūānuku and Ranginui.

Atua, god, first woman.

A branch of philosophy concerned with the nature of being, existence, or reality. Ontology considers the assumptions that we make about what kinds of things exist (e.g., health, illness), and how they come into being.

Refers to genealogy and layers of genealogy. The Māori worldview describes human life as descending from gods, and as related to the natural environment; the structure by which all things are connected (Barlow, 1991). Reference: Barlow, C. (1991). Tikanga whakaaro: Key concepts in Māori culture. Oxford University Press.

The process of establishing relationships.

Describes the spiritual and unseen; central to a Māori worldview about reality and human life; the ultimate reality of existence for Māori (Marsden, 1992). Reference: Marsden, M. (1992). God, man and universe: A Māori view. In M. King (Ed.), Te ao hurihuri aspects of Māoritanga (pp. 117–137). Reed Publishing.

The branch of philosophy concerned with the nature, scope, and limits of knowledge. That is, how we know what we know. In critical health psychology, epistemology is intertwined with considerations of power, positionality, and the politics of knowledge. Critical health psychologists are often open to multiple ways of knowing, aligning with plural, situated, and reflexive epistemologies, as a deliberate move away from the hegemony of positivist epistemologies that dominate mainstream health psychology.

Māori narratives or stories.

A body or continuum of Māori knowledges; refers to something unique and valuable about the Māori world (Royal, 2012); encompassing of all branches of Māori knowledges, including past, present, and still developing (Mead, 2016). References: Mead, H. (2016). Tikanga Māori: Living by Māori values. Huia; Royal, T. A. C. (2012). Politics and knowledge: Kaupapa Māori and Mātauranga Māori. New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies Te Hautaki Mātai Mātauranga o Aotearoa, 47(2), 30–37.

Māori customs and correct processes.

A significant Māori saying or proverb with unknown origins.

Prayer, incantation, chant.

Song.

Lament, traditional chant, sung poetry.

Traditional healing practices and medicines.

A star constellation (Pleiades) signalling the Māori new year.

A Māori approach embedded in Māori knowledges and worldviews.

Translates in English to language nest, referring to Māori early childhood education. Focuses on total immersion in Māori language and values for preschool children.

Māori immersion primary schools.

Independence, self-determination, sovereignty; referring to independence, as a provision of Article 2 of Te Tiriti o Waitangi.

Research theory and practice that emphasises Māori cultural ways and knowledges, with a focus on transformative outcomes for Māori (Smith, 2017). Reference: Smith, G. H. (2017). Kaupapa Māori theory: Indigenous transforming of education. In T. K. Hoskins & A. Jones (Eds.), Critical conversations in Kaupapa Māori (pp. 70–81). Huia.

From a critical theory perspective, this entails a cycle of engaging with theory, taking action, and reflecting and critiquing the action to then inform the theory, and so on.

Pacific Ocean.

Chief, leader.

The Declaration of Independence, signed in 1835, declaring the independence of rangatira and asserting Aotearoa New Zealand as an independent state.

The specific terms of agreement within the text of Te Tiriti o Waitangi and The Treaty of Waitangi.

The current day consideration of the terms of agreement of Te Tiriti o Waitangi and The Treaty of Waitangi.

A New Zealander of European descent, often a form of positive identification in relation to te ao Māori.

Referring to governance, as a provision of Article 1 of Te Tiriti o Waitangi.

Spiritual authority or power.

Referring to all of the rights as a provision of Article 3 of Te Tiriti o Waitangi.

Referring to Māori spiritual practices, as a provision of Article 4 of Te Tiriti o Waitangi.

Independence, authority, sovereignty.

A healthcare approach that focuses on recognising, respecting, and responding to the cultural identity of patients, and addressing power imbalances in the healthcare encounter.