2.3. Diagnosis as a social and political practice

Tracy Morison and Clifford van Ommen

Overview

In this chapter, we examine diagnosis not just as a process of labelling diseases, but as a practice that establishes a shared understanding of what constitutes sickness—an understanding shaped by values, norms, and biology, and imbued with significant social consequences (Jutel, 2024). We begin by asking, “What is diagnosis?”—exploring how naming and framing create diagnostic systems that often struggle with ambiguity.

Next, we examine diagnosis as a social tool. In medical interactions, healthcare providers wield the “power to name,” raising questions:

- Who benefits from specific diagnoses?

- What role do they play in maintaining the status quo and, hence, social inequity?

We also consider diagnosis in the context of medicalisation, whereby everyday experiences are reframed as medical issues through diagnostic classifications. We discuss the benefits, such as validation and care, and drawbacks, including stigma and oversimplification, associated with this practice.

Learning objectives

By the end of this chapter, readers will be able to:

- Describe the communicative and validating functions of diagnosis.

- Distinguish between diagnosis as a noun (label) and as a verb (process).

- Name the key points of consensus underlying the provision of a diagnosis.

- Describe how the process of diagnosis rests on a knowledge hierarchy that shapes the doctor/patient relationship.

- Provide examples of how diagnoses are historically and culturally embedded.

- Describe how the process of diagnosis is embedded within and influenced by larger institutional and social contexts.

- Explain the sociopolitical consequences of the process of medicalisation.

Introduction

Diagnosis is a fundamental tool in scientific Western medicine (Jutel, 2019b; Radley, 2013) and, therefore, shapes modern understandings of health and illness (Brown, 1995). At its core, diagnosis involves “putting a name to an ailment” (Jutel, 2019a, p. 290)—a process of labelling an illness that identifies what is abnormal and in need of treatment. This process explains what is happening to the body and guides treatment to restore normalcy. The diagnostic process involves assigning clinical observations about the body (signs) and patient experiences (symptoms) to predefined categories (Brown, 1995; Jutel, 2021). From a critical health psychology perspective, this process is an interpretative practice. It involves labelling and categorising based on judgments of ab/normality, entwining specialist knowledge and power (Durie, 2004; Rose, 2013).

The practice of diagnosis is about more than curing; it carries profound personal and social consequences. A diagnosis provides a gateway to treatment and resources (e.g., government-funded care, insurance benefits), but can also reframe an individual’s lifestyle (such as eating, physical activity, and alcohol consumption) as symptomatic of a medical condition. For instance, a diagnosis of Type 2 diabetes may validate experiences like fatigue, low energy, and weight changes while granting access to treatment. However, this reductionist framing prioritises lifestyle factors over contextual issues (e.g., access to nutritious food or safe exercise spaces), potentially subjecting individuals to increased scrutiny and blame, reinforcing stigma, and narrowing their identity to “unhealthy” practices.

Thus, diagnostic labelling can also result in diminished social roles, restricted access to resources, or even being denied opportunities, further isolating some individuals in society. Conversely, the absence of a diagnosis may leave those with contested or unexplained illnesses unrecognised and unsupported (Dumit, 2006; Rose, 2013). Beyond the immediate individual ramifications, diagnosis also plays a role in legal decisions, public health planning, and resource allocation, as summarised in Textbox 1.

Textbox 1. The wider social functions of diagnosis (Rose, 2013)

(ii) legal decisions, such as detention in jail or treatment under state care;

(iii) resource allocation within medical and educational systems;

(iv) distributing research funding;

(v) epidemiological and public health planning; and

(vi) organising service provision.

Given these far-reaching social and material ramifications, critical health scholars argue for studying diagnosis as a social and political practice (Jutel, 2021; Rosenberg,2002; Thompson, 2021). To explore this, we follow the sociological differentiation between:

- diagnosis as a noun or “thing,” asking, “What is diagnosis?” and

- diagnosis as a verb or practice, asking, “How is diagnosis conducted?” (Blaxter, 1978; Jutel, 2021).

This discussion raises some fundamental issues of particular interest to critical health psychologists, including how decisions about normality and abnormality are made, who gets to decide this, and on what basis.

1. What is diagnosis? Diagnosis as a noun

A diagnosis offers a way to classify and organise various health conditions in ways that are useful to healthcare professionals. Medical diagnosis involves labelling an illness experience using a predetermined set of diagnostic categories (Rose, 2013; Jutel, 2021). Diagnostic categories and classification systems were created for professional communication and to facilitate medical research and teaching. Common diagnostic categories allowed a common language or standard for healthcare professionals to share information, plan treatments, and conduct research effectively and collaboratively. This standardised approach is essential for the organisation and delivery of healthcare services. Standardisation was motivated by public health imperatives, such as tracking the prevalence and incidence of diseases to inform policies and interventions (Blaxter, 1978; Jutel, 2021). Those who experienced the 2020 global pandemic can no doubt attest to this valuable function.

Without detracting from these useful functions, Ward (2019) maintains that while offering a useful way of summarising a pattern, the power of a diagnosis to simplify can be harmful. Drawing on the concept of “terrible simplification (terrible simplificateur)”—which refers to explanations disregarding complexities and the broader context—he notes three problems. The first is potentially neglecting the complexity and nuance of what a person is going through because the diagnostic process narrowly focuses on biological elements (disease) rather than the social meaning of a condition (illness) (Berndt & Bell, 2021).

For instance, Ward argues, “If you are in despair, it might be worse than useless to be told ‘you’ve got depression’” (p. 19). This is problematic because it reduces a multifaceted, deeply personal experience to a simplistic label, potentially alienating individuals by neglecting the unique and complex nature of their emotional distress. This reduction might arguably be less concerning in the context of acute infectious diseases, such as COVID-19, but can have consequences, especially for those with chronic or complex conditions. Such conditions are multifaceted; a simple diagnosis may overlook the interplay of physical, emotional, and social factors, and promote treatments that do not fully address what the patient experiences as a problem.

The second issue with simplification is that diagnostic categories can strip away humanity in medical encounters. Even accurate clinical diagnoses can reduce individuals to mere labels, Ward (2019) argues. This is evident when medical students casually refer to “the heart failure in bed ten,” reducing the person to their diagnosis, or when “Alzheimer’s disease” is assumed to account for everything a person experiences. This reductive approach, characteristic of the biomedical model (see Chapter 2.1.), can strip people of their personhood.

The third and final issue is that when diagnoses oversimplify complex issues, essential aspects can become invisible. The focus tends to shift toward clinical or biological symptoms rather than contributing factors like the underlying social determinants. For example, in the case of obesity, economic deprivation is a crucial factor because limited financial resources often restrict access to nutritious foods, safe exercise environments, and quality healthcare. Neglecting these economic dimensions creates a paradox where illness is simultaneously defined and obscured—a “way of knowing and not-knowing illness” (Ward, 2019, p. 28)—that fails to address the root causes of the condition.

Having explored what diagnosis entails, it is crucial to recognise that the seemingly neutral process of diagnostic classification is, in fact, a nuanced act of interpretation. Although it appears objective, diagnosis involves naming and framing illnesses—organising them into distinct categories with clear boundaries.

Diagnosis as “naming and framing”

Diagnostic categories are most often thought of as simply describing bodily phenomena caused by biological processes, “real” entities that exist “out there”, independent of the diagnostic process and outside of the socio-cultural realm (Jutel, 2021). Diagnosis is, therefore, taken for granted as a benign medical tool drawing on classifications assumed to be neutral and objective because they are grounded in medical science (Bourdieu, 1991). Jutel (2021, p. 71) cautions that such thinking “can disguise ideology and convey the illusion of neutrality.” Although diagnostic classification appears neutral and objective, as we stated at the start of this chapter, diagnosis is a process of interpretation and categorisation.

Frameworks for diagnosis—like the World Health Association’s International Classification of Diseases (ICD) or the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) of Mental Disorders—are created by arranging illnesses into groups divided by clear boundaries (the process of framing) (Brown, 1996). This inherently involves judgment and selection as medical experts decide where boundaries should be placed to create useful categories for understanding and treating health conditions (Jutel, 2011). Each classification results from human decision making involving agreement about what should be categorised in what way, rather than being a fact of nature (Jutel, 2021).

Frameworks for diagnosis are thus formed by social actions and consensus among medical experts (Aronowitz, 2001). These actions determine what counts as a disease, how it should be classified and understood, and who has the authority to make these decisions. This consensus involves several key components, as shown in Textbox 2.

Textbox 2. Key components of diagnosis

- What Counts as a Disease? Deciding what constitutes a disease involves social judgments about which conditions are considered normal and which are seen as pathological. These decisions are influenced by contemporary medical knowledge as well as social attitudes and cultural beliefs.

- Classification and Understanding: Medical science and social contexts shape how diseases are classified and understood. This includes the criteria used to define a disease and the theoretical frameworks that guide our understanding of different health conditions.

- Authority to Diagnose: Not everyone has the authority to diagnose; this power is usually reserved for professionals whom societal institutions have granted this role. This gatekeeping role includes giving permission to be ill, which confers legitimacy on the patient’s condition.

- Social Goods and Benefits: The act of diagnosing carries significant social implications. Being diagnosed can provide access to social goods and benefits, such as medical treatment, social support, and economic resources. However, it also involves labelling individuals, which can have broader social consequences, as alluded to above.

Thus, diagnoses are never “just” descriptive. They are not neutral reflections of biological facts. Rather, they are entangled with the social and political currents of their time, underscoring the importance of examining diagnoses within their historical and social contexts to highlight the underlying values and norms (Dumit, 2006).

The role of values and norms in creating diagnoses

The creation of diagnostic categories is not purely a scientific endeavour but one embedded within a cultural context. Cross-cultural and historical comparisons draw attention to the social dimensions of diagnosis (Barker, 2010). They show how changes in diagnoses across place and time are not solely due to the evolution of scientific knowledge and medical advancements but also reflect fundamental shifts in how disease is conceptualised. In this sense, diagnoses often reflect the social and moral contexts in which they emerge (Blaxter, 1978). (Recall from Chapter 2.1 how societal values and norms influence which conditions are recognised as diseases and how they are understood.)

Historical analyses of diagnoses show that shifting cultural values around gender, race, and sexuality have played a pivotal role in redefining what is considered “normal” and “abnormal” behaviour (Tyson, 2011). We have alluded already (in Chapter 2.1) to the classification of “hysteria” in the 19th century as a reflection of Western cultural attitudes toward women’s mental health and social norms of gendered behaviour, which are today largely considered less valid (Marecek & Lafrance, 2021). Two other useful historical examples, drapetomania and homosexuality, illustrate how Western conceptualisations of mental illness have been influenced by cultural and social forces rather than objective medical findings alone (Tyson, 2011; Olafsdottir, 2013). You can read more about these in Textbox 3.

Textbox 3. Two historical diagnoses: drapetomania and homosexuality

Drapetomania, described in 1851 by American physician Samuel Cartwright, was a mental illness that affected enslaved Africans who wanted or tried to flee captivity. Cartwright suggested that this “disease” was caused by enslaved people forgetting their god-ordained role to serve their White masters. While this diagnosis might seem absurd by today’s standards, it was rooted in the racial ideologies of the time (Tyson, 2011). Slavery was normalised and even justified by pseudo-scientific arguments about innate biological differences between “races” of humans that make some superior and others inferior (Böhmke & Tlali, 2008; Tuffin, 2017). Drapetomania thus reflected broader social values that dehumanised African people and enforced their subjugation. It was not scientific advancement but rather changing social norms around race and human rights, facilitated by the abolitionist movement, that led to the abandonment of drapetomania as a legitimate diagnosis (Tyson, 2011).

The classification of homosexuality as a mental disorder, included in the first edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) in 1952, was shaped by societal attitudes towards sexuality. In the 19th and early 20th centuries, homosexuality was pathologised, with psychiatrists like Karl von Westphal and Richard von Krafft-Ebing claiming it was caused by genetic abnormalities or moral deviance. These classifications reflected prevailing moral and religious beliefs that viewed heterosexuality as normative and other sexual orientations as deviant. Homosexuality was removed from the DSM in 1973, not because of new scientific discoveries but due to changing social values and the influence of the civil rights movement, which pushed back against pathologising sexual diversity (Tyson, 2011). Drescher (2015) identifies gay activism as the salient catalyst in provoking debate within the American Psychiatric Association (APA), ending in a vote which removed homosexuality from the DSM. Thus, through a social process (voting), homosexuality stopped being, at least within the APA, a mental illness and millions of US American citizens were almost instantly de-pathologised.

As in history, today, we see significant variations in diagnoses across cultures. For instance, differing beliefs about childhood behaviour and norms are reflected in the recognition and categorisation of psychological conditions like attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) (Dew et al., 2016; Fawcett et al., 2020). ADHD diagnoses have mostly been limited to Anglophone countries (Horton-Selby, 2018). Behaviours indicative of ADHD in UK classrooms are given more contextual attributions (e.g., the behaviour being due to classroom and parenting strategies) in Korea, Denmark, and France (Horton-Selby, 2018; Nielsen, 2018).

Even physical illnesses have faced varying degrees of recognition and attributions of legitimacy across different societies (Dumit, 2006). Myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME), also called chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS), is a case in point, showing how cultural context can shape the acceptance and understanding of medical diagnoses (Aronowitz, 2001). Numerous doctors have been found to not diagnose this condition. In Europe, for example, Pheby et al. (2020, p. 6) state that a “high proportion of GPs [General Practitioners], which is likely to be at least 50%, do not recognise ME/CFS as a genuine clinical entity and therefore do not diagnose it”. However, this varies depending on the country and even the particular region within a country. Official state recognition of ME/CFS as a diagnosis also did not mean that a GP would recognise it as a “genuine entity”. Furthermore, recognising the diagnosis as legitimate did not translate into GPs having confidence in diagnosing and treating ME/CFS or having specialist services to which to refer patients.

The subjective human aspect of diagnostic categories becomes particularly evident when considering how diagnoses change over time and across different cultures, as well as in disputes around illnesses, such as contested or medically unexplained conditions. Such cases of contestation or uncertainty also bring “issues of power and control over legitimation of illness … into sharp relief” (Denny, 2009, p. 998), as we discuss in the following section where we consider the doing of diagnosis, diagnosis as a verb or practice.

2. How is diagnosis conducted?

As much as it is a useful tool, diagnosing is also a social and political act in the sense that it takes place within social relationships. These relationships are imbued with power and perform various social functions in addition to practical medical functions. As we discuss below, diagnosing structures the patient’s relationship with the medical professional, privileging certain types of knowing and consequently placing the doctor in a powerful position. However, doctors also work within a larger social-political context, which includes a range of other stakeholders (e.g., insurance and pharmaceutical companies) who influence the diagnostic process, including by conferring legitimacy and access to funding.

Healthcare interactions, power and knowledge

Providing a diagnosis is an essential process that organises illness, as we have discussed, and structures the medical relationship (Jutel 2019). Diagnosing is, therefore, a critical point in medical interactions, specifically regarding the roles of healthcare providers and patients. The process requires patients to submit to the healthcare provider’s expertise, thus establishing power dynamics within healthcare interactions. These dynamics are underpinned by entrenched hierarchies of knowledge that shape how different forms of understanding are valued in medical settings.

A major reason for power imbalances in medical interactions is the knowledge hierarchy that structures lay-professional relationships (Dew et al., 2016). Patients and professionals rely on different knowledge bases to understand health issues and to engage with each other, with one form typically valued over others. Biomedical knowledge is a formal, professional, and authoritative form of knowledge. Seen as objective, it concerns the disease process and the unquestionable “truths” about medical science. In contrast, “lay expertise” or “experiential knowledge” is practical knowledge embedded in the patient’s experience of managing and living with an illness (Dumez & L’Espérance, 2024). This form of knowledge is often granted less authority by professional “hearers” (Dew et al., 2016). However, these boundaries are not always clear-cut: movements toward recognising the “expert patient” and the development of detailed “lay epidemiologies” in the context of healthism (Crawford, 2006) challenge the rigid separation between lay and professional knowledge. Even so, in many diagnostic encounters, experiential and embodied forms of knowing continue to be dismissed or devalued.

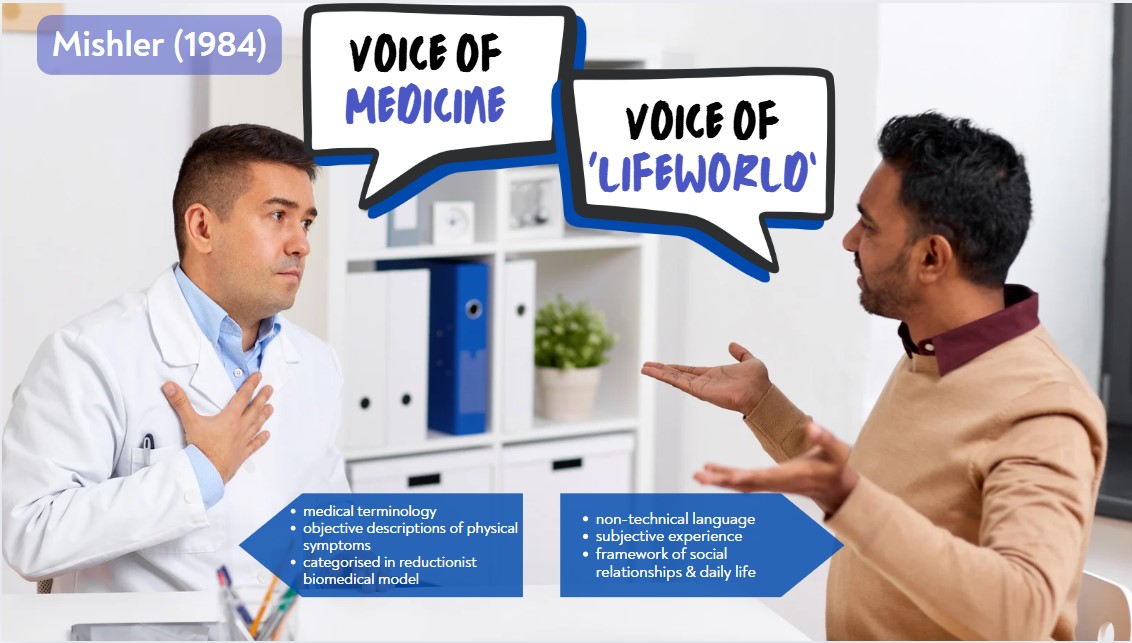

This divergence was highlighted in the foundational work of psychologist Elliot Mishler (1986). Mishler showed how patients and physicians communicate using distinct “voices.” Doctors use “the voice of medicine”, comprising medical terminology, objective descriptions of physical symptoms, and categorisations of these within a reductionist biomedical model. Patients use “the voice of the lifeworld,” comprising non-technical language and expressing the subjective experience of sickness inside the framework of social relationships and the patient’s daily existence. Mishler’s study illuminated modern Western medicine’s tendency toward paternalism and hierarchy that tend to minimise or dismiss patients’ knowledge of their circumstances and experiences.

Given doctors’ greater power to establish the structure of the interaction with patients, patients may experience their voice as being overruled and shut down, with the doctor’s explanations wiped of individual meaning and social context. For example, a patient suffering from chronic pain might want to discuss how the condition affects the ability to work and care for others. At the same time, a health provider might be inclined to focus on prescribing medication, overlooking the broader context of the patient’s life.

Diagnosis often reinforces this hierarchy, privileging biomedical criteria over other ways of knowing. Expert knowledge is grounded in the biomedical model and focuses narrowly on biological, measurable, and quantitative elements. Accordingly, the expert knowledge health providers hold is considered objective and, therefore, more trustworthy than the subjective, possibly unreliable, information patients bring to consultations. In contrast, patients, as laypeople, are at a disadvantage because the knowledge of biomedicine is largely inaccessible to them. Instead, patients draw on embodied knowledge of illness gained through experience (Berndt & Bell, 2021).

Embodied knowledge develops over time from “knowing one’s body”, as Corbin (2003, p. 258) puts it. These findings are supported by subsequent research highlighting diagnosis as “a point at which medical authority often dominates rather than negotiates” (Jutel, 2019a, p. 290). Health professionals are often found to minimise, dismiss, or even disparage patients’ experiential or embodied knowledge (Dumez & L’Espérance, 2024). At worst, such dismissals can lead to medical gaslighting, where patients’ own experiences are questioned or invalidated, making them doubt the reality of their symptoms. This deepens the power imbalance in clinical encounters and leaves patients feeling further disempowered and isolated (e.g., Fielding-Singh & Dmowska, 2022; Morison, Ndabula, & Macleod, 2023; Penny, Moewaka Barnes, & McCreanor, 2011).

Likewise, Indigenous knowledge is frequently dismissed in diagnostic encounters as no longer relevant today. However, Māori psychiatrist, researcher and activist Mason Durie (2004, p. 1142) argues, “While clinical views will inevitably focus on a particular diagnostic grouping, clinicians must also exercise judgement about the relationship of the disorder to other aspects of healthy living.” The holistic view offered by Indigenous models of health (such as the Māori health model Te Whare Tapa Whā discussed in Part One) can, therefore, be helpful when understanding illness experiences. Durie (2004) maintains that Indigenous ways of knowing are not just culturally significant—they are also key health determinants. He cites a study in which older Māori who scored lower on the cultural index (indicating weaker ties to their traditional values and practices) were more likely to experience poorer health outcomes. Such findings challenge the knowledge hierarchy, showing that Indigenous knowledge offers valuable insights into a holistic view of health, and support calls for integrating other forms of knowledge into healthcare practices and policy. Both expert and lay forms of knowledge are, therefore, important for successfully treating patients.

While healthcare providers have the power to diagnose—and thus act as gatekeepers to resources and recognition—they do so within systems shaped by broader institutional and societal power structures (Jutel, 2019b; 2024). Therefore, the power dynamics of diagnosis extend far beyond the doctor-patient relationship and interpersonal interactions in medical settings. Diagnosis is thus both a clinical activity and a socio-political act (Jutel, 2021), as we discuss further below.

The broader politics of diagnosis

Diagnosis plays a crucial role in the social negotiation of illness and access to the sick role (discussed in Chapter 2.2), as medical experts grant “permission to be ill” (Nettleton, 2006, p. 1167). The act of diagnosing an illness occurs within and is mediated and regulated by the broader socio-political context, including institutions and societal values and norms (Dumit, 2006). For instance, Dumit (2006, p. 587), discussing contested illnesses, points out that various stakeholders—such as insurers, governments, and industry—”have a vested interest in denying and dismissing claims of chronic illness where they can get away with it”. Consequently, the struggle to obtain a useful diagnosis experienced by people with medically unexplained or contested illnesses is not simply about convincing a healthcare professional (Anleu, 2009; Bell et al., 2024; Nettleton, 2006).

Therefore, diagnosis is important for individuals because of its role in the social sanctioning of illness, as highlighted in cases where people fail to receive diagnoses of their physical ailments. Textbox 4 illustrates the effects of diagnostic uncertainty on the social sanctioning of illness and how this impacts individuals with medically unexplained symptoms.

Textbox 4. Diagnostic uncertainty and social sanctioning

Diagnostic uncertainty refers to the inability to definitively determine a diagnosis due to incomplete, ambiguous, or conflicting clinical information. It is closely related to contested illnesses and medically unexplained symptoms because both involve conditions where a clear, widely accepted diagnosis is difficult to establish or remains elusive (Jutel, 2021b).

The term “medically unexplained symptoms” describes cases in which people report symptoms for which doctors cannot identify an organic cause. In other words, there is no known medical explanation for the symptoms they are experiencing (Nettleton, 2006). Examples include chronic pain, chronic fatigue, gastrointestinal issues, and other bodily complaints that conventional diagnostic tests cannot explain.

Contested illnesses are conditions where there is disagreement or lack of consensus within the medical community about the existence, causes, or appropriate treatments for the illness. Examples include conditions like chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS/ME), fibromyalgia, and multiple chemical sensitivity (Murphy, Kontos, & Freudenreich, 2016).

Living without a clinical diagnosis or a medical justification of their symptoms has negative consequences for many people. Research highlights an overall experience of struggle and invalidation for people living in “diagnostic limbo” (Nettleton, 2006), due to being met with scepticism and mistrust from both health professionals and other people (Mengshoel et al., 2018; Rossen et al., 2019). Such responses challenge these people’s credibility and dignity. Those with medically unexplained symptoms therefore often experience their identities as threatened (Rossen et al., 2019).

In this regard, a common experience is of having to struggle against the negative characteristics regularly imposed on a person with an unexplained or contested illness. These include, for example, being “whinger” (Mik-Meyer, 2011. p. 36), weak (Denny, 2009), or a lazy opportunist or workshy (Shaefer, 2005; Mengshoel & Heggen, 2004), and similar negative labels that question moral character. As a result, they engage in “constant identity negotiation” (Rossen et al., 2019, p. 551), constantly resisting negative identities and striving to attain one that is socially acceptable. Some even report the sense of having lost their identity, “seeing themselves as a ‘nobody’” (Engebretsen & Bjorbækmo, 2019, p. 1023).

In addition to legitimation for individuals, diagnostic labels also play a role in societal judgments about which conditions count as legitimate illnesses and/or are “worthy” of attention and are used in shaping public policy and societal priorities (Brown et al., 2012). For instance, widely recognised and diagnosed conditions (such as heart disease or cancer) receive significant funding and attention in medical research and public health campaigns, while others (like certain chronic pain or women’s health conditions) do not (Hudson, 2022). These judgements shape public perception and social reception of certain diseases (discussed in Chapter 2.2) and also play a role in creating healthcare disparities (Brown et al., 2012; Gibson et al., 2017).

The final political function of diagnosis that we consider is social control. As we have argued, diagnostic categories are based on human judgment and consensus among medical professionals regarding what is considered “normal” and “abnormal” health, judgments that draw on and reflect broader societal values and norms (Smail, 2005). Consequently, the criteria on which diagnoses are based have been shaped by political and social agendas, reflecting and perpetuating dominant ideologies in the interests of the powerful (Hook, 2004; Parker et al., 1996; Shefer, 2004). Given that the power to name what is normal or pathological resides with those in power, diagnoses can be imposed on people and work as a way of delegitimising and controlling individuals and the social groups to which they belong (Olafsdottir, 2013). In this way, diagnosis can serve as a tool of social control by legitimising and reinforcing certain dominant social ideologies and marginalising others (Parker et al., 1996; Smail, 2005).

One of the most prominent examples of a diagnosis wielding power is the DSM, the authoritative guide used by clinicians to diagnose mental disorders. Mental health diagnoses can reframe common emotional experiences, behaviours, or practices as a medical disorder, transforming how society understands and responds to them (LaFrance & McKenzie-Mohr, 2013; Marecek & LaFrance, 2021). By labelling certain behaviours or conditions as pathological, diagnosis can reinforce societal norms and exclude alternative ways of living or understanding health. Those who step outside the bounds of social acceptability can be labelled as pathological and in need of treatment.

This process of pathologisation was evident in the earlier examples of diagnoses of Drapetomania and homosexuality to control enslaved people and gay men, respectively. Other examples include the diagnoses of nymphomania, hysteria, and, more latterly, female orgasmic disorder, used to regulate women’s sexual behaviour (Marecek & LaFrance, 2021; Potts, 2008; Thomas & Gurevich, 2021). Attempts to exercise social control through diagnosis can be most extreme in regimes whose hold on power is explicitly challenged by its citizens. The historical use of psychiatry in the then-Soviet Union to suppress dissent has been well documented (Bonnie, 2002). Far more recently, we have reports of students involved in the “Woman, Life, Freedom” protest in Iran being sent to psychological centres to be “reformed” or forcibly admitted to psychiatric hospitals (Hooshyari, 2024).

3. The double-edged nature of diagnoses

We hope we have convinced you that diagnostic labels are not simply descriptive. They can have profound social effects, influencing everything from personal identity to legal status and the allocation of resources like disability benefits (Dumit, 2006; Radley, 1994). We want to emphasise that the process of diagnosis is in and of itself neither good nor bad. However, diagnostic labels can be used to serve particular interests, and these labels can be double-edged.

Diagnosis is a valuable tool for providing helpful information about populations and advancing medical science. Diagnoses provide explanations of what is happening to a body, the likely progression and outcome of a condition (prognosis), and how to treat it (treatment or intervention). Oftentimes, a diagnostic label points towards a plan of action that might otherwise not have been evident, such as the need for particular care and assessment for suicidal feelings in cases of depression (Ward, 2019). Obtaining a diagnosis makes people’s conditions recognisable to others around the ill person and thereby “promises a label that validates patients’ embodied experiences and a road map for living with and treating illness” (Boulton, 2019, p. 809). Receiving a diagnostic label can, therefore, help legitimise the experiences of those suffering from illness, affecting not only how others see and respond to them but also how they see themselves and experience their illness (Bülow, 2008).

Diagnoses can help to support and shape an individual’s social identity. Receiving a diagnosis can provide meaning to an otherwise chaotic experience, becoming an anchor or turning point in the person’s illness narrative (Riessman, 2015; Werner et al., 2003). Diagnosis influences how individuals understand their health conditions and plays an influential role in shaping illness experiences. For example, Lafrance and McKenzie-Mohr (2013, p. 214) state that a typical response to psychiatric diagnoses is “the expression of relief and validation,” as the labelling of distress by an expert can normalise and legitimise people’s experiences.

At the same time, however, diagnoses can reinforce or challenge social norms and stigmas. In some cases, being diagnosed with an illness can challenge a society’s cherished values and norms. For example, a diagnosis of HIV has historically been associated with significant stigma, particularly in Western societies where the illness contravenes dominant norms surrounding sexuality, health, and morality (GLAAD, 2022). HIV is often linked to behaviours such as non-heteronormative sexual practices or intravenous drug use, which challenge traditional Western ideals of sexual conservatism, bodily purity, and self-discipline. As a result, the illness has frequently been seen as a marker of “moral failure,” reinforcing perceptions that those who contract it have violated societal expectations about acceptable behaviour. This association with norm-breaking behaviours places those living with HIV at risk of moral judgment, and continues to affect public attitudes toward the condition.

Some diagnoses, as discussed previously (in Chapter 2.2), may carry stigmas that affect how others perceive and treat individuals, leading to discrimination and marginalisation. Continuing the above example, advancements in medical treatments of HIV have transformed it into a manageable chronic condition, but despite this, it remains highly stigmatised in many contexts. This stigma can manifest in discriminatory practices in healthcare, employment, and social relationships, where individuals may be treated differently due to their diagnosis (ViiV Healthcare, 2025). For instance, the persistence of stigma around HIV reflects more profound anxieties in society about illness, morality, and deviance from social norms, illustrating how diagnoses can function for the purposes of social exclusion (Campbell, 2004).

On the other hand, diagnoses can also challenge existing stigmas by increasing awareness and understanding of certain conditions, promoting social change and acceptance (Campbell, 2004). For example, the increased visibility and advocacy around mental health conditions such as depression and anxiety have helped to reduce stigma in many parts of the world. Where mental illness was once heavily stigmatised and often seen as a personal failing or weakness, greater public education and the sharing of lived experiences have reframed these conditions as legitimate health issues that require support and treatment.

The above discussion demonstrates the significant social, psychological and material consequences of the practice of diagnosis. It shows also how diagnosis is a medical practice that is deeply embedded in the norms and values of society. For a condition to become an object of interest to medicine, it needs to be interpreted or framed as a medical issue. Diagnosis is the first step in transforming a non-medical issue into a medical one, initiating a process called medicalisation. This process—framing and treating previously non-medical problems as illnesses, disorders, or syndromes—is a notable feature of industrialised, Westernised societies (Anleu, 2019; Olafsdottir, 2013).

4. Medicalisation and the shifting boundaries of sickness

An article reporting on a newly discovered disorder called motivational deficiency disorder (MoDeD) caused a stir when it appeared in the British Medical Journal, with news outlets reporting on this in alarm (Mirsky, 2006). The article stated:

Extreme laziness may have a medical basis, say a group of high-profile Australian scientists, describing a new condition called motivational deficiency disorder (MoDeD). The condition is claimed to affect up to one in five Australians and is characterised by overwhelming and debilitating apathy. Neuroscientists at the University of Newcastle in Australia say that in severe cases, motivational deficiency disorder can be fatal because the condition reduces the motivation to breathe (Moynihan, 2006, p. 745).

A campaign was designed to raise awareness about MoDeD, including this video, “A new epidemic.”

After watching this clip, you will no doubt realise that motivational deficiency disorder, or “MoDeD,” is a fictitious diagnosis. The journal article we quoted was published on “April Fool’s Day” and part of a campaign aimed at highlighting “disease mongering”, the widespread practice of exaggerating and promoting non-existent diseases (Mirsky, 2006), including the media’s role in adding credibility to and feeding the worry underlying disease mongering (Cassells, 2008; Germov & Freij, 2019).

The fictitious case of MoDeD humorously illustrates the widening boundaries of what counts as a disease due to changing understandings of health and illness. It shows how diagnoses can medicalise behaviours and conditions that are not necessarily the result of bodily dysfunction or pathogens, bringing these under the purview of healthcare professionals.

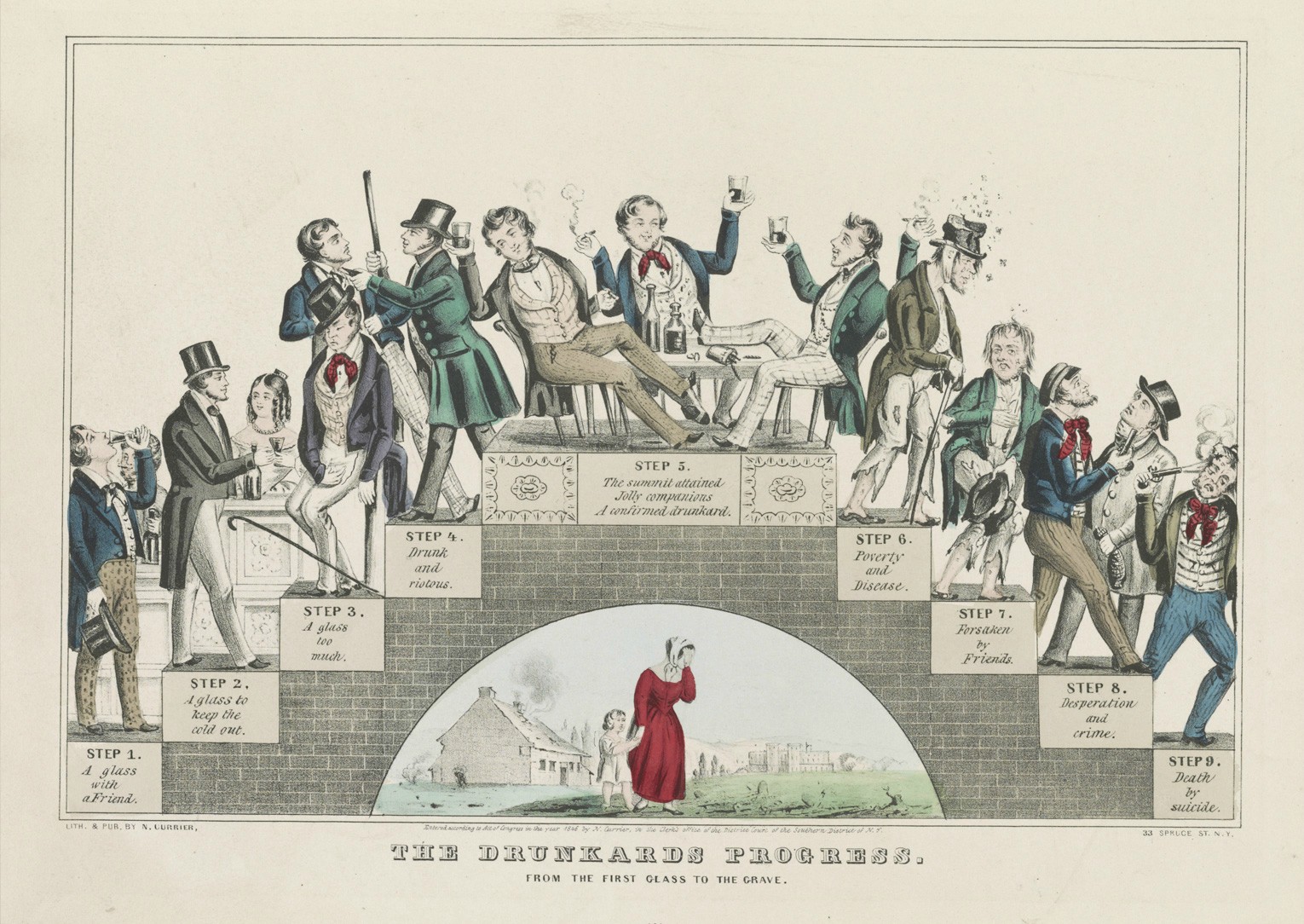

Medicalisation is “the process by which conditions, experiences, and situations, which were at one time not seen as medical in nature, come to be seen as medical. They thus come under a medical jurisdiction for treatment” (Dew et al., 2016, p. 95). Medicalisation is widespread, as an ever-widening range of human practices and experiences are classified, experienced, diagnosed, and treated as medical conditions (Barker, 2010). For example, conditions such as alcoholism, menopause, baldness, obesity, and even ageing (Pickard, 2011) have been medicalised (Dew et al., 2016). Table 2.3.1 provides an overview of how different spheres of life are brought into the medical domain, leading to management and treatment.

| WHAT’S BEING MEDICALISED? | “Deviance” (behaviour deviating from societal norms) | Natural life process | Everyday problems of living | Enhancements in healthy people |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| EXAMPLE | Excessive alcohol or substance use | Ageing | Worry | Athletic/cognitive performance, appearance |

| CONCEPTUAL SHIFT | “badness” ➡️ “sickness” | natural processes/life events ➡️ medical-technical problem | common, expected feelings ➡️ medical pathology | well ➡️better-than-well |

| WHO/WHAT DRIVES PROCESS? | The state, social interest groups, or movements (treat “alcoholics” rather than punish social “deviants”) |

Medical specialities (e.g. psychiatry), consumers |

Pharmaceutical companies, psychiatry, consumers, patient advocacy groups | Pharmaceutical companies, medical specialities (e.g. cosmetic surgery), consumers |

| CRITIQUES

|

Attention on the individual overlooks the social environment & limits solutions

|

Narrows definition of normality

Lay/Indigenous knowledge undermined Increases medical surveillance & control & diminishes people’s autonomy |

Attention on the individual overlooks the social environment & limits solutions

Less tolerance for minor discomfort or problems False promises Homogenises life |

Privileges the well-off & undermines social solidarity (between rich & poor)

Individualistic: Promotes individual over collective interests Promotes suspect norms |

Once an illness is medically classified, pharmaceutical companies and entrepreneurial influencers can develop and market treatments, driving the expansion of diagnostic categories (Moynihan et al., 2019; 2020). For instance, the diagnostic expansion of conditions like ADHD or depression has coincided with the development of corresponding medications, leading to lucrative markets (Horton-Selway, 2018; Nielson, 2018). Diagnosis is, therefore, not just about identifying disease; it is also a gateway to treatment and profit, where medical and economic interests intersect. Commercial interests frequently drive medicalisation, from companies manufacturing cures to advertisers and media outlets reporting on sensational health issues (Moynihan et al., 2019, 2020).

In recent decades, the “machinery of medicalisation” has mushroomed, involving medical professionals, allied health organisations, social movements, consumers, biotechnology, the insurance industry, and the pharmaceutical industry (Moynihan et al., 2019; 2020; Tiefer, 2008). Pharmacological solutions have abounded in recent years for a host of “conditions” (Marecek & Hare-Mustin, 2009), for example, those related to ageing (e.g., baldness, hormone replacement therapy), emotional distress (e.g., depression, anxiety), and sexuality (e.g., erectile dysfunction, labiaplasty, female orgasmic disorder). The authority of diagnostic systems is thus deeply intertwined with the economic interests of industries such as pharmaceuticals (Moynihan et al., 2019; 2020), prompting critiques of disease mongering for financial gain, as highlighted by cases like MoDeD and protests against Pink Viagra (Moynihan, 2010; Tiefer, 2006; see Textbox 6 further below).

Medicalisation has legitimised branches of medicine, such as psychiatry—a subfield of medicine—extending its influence and conferring greater authority on associated disciplines like clinical psychology (Shorter, 1997). For example, alcohol use or problematic gambling can be “diagnosed” as stemming from addiction, personality disorder, or depression, and psychiatrists may even be involved in matters related to legal norms, such as child abuse or rape (Anleu, 2019). Consequently, psychiatry—and the psy professions more broadly—now oversees a range of aspects of life, including sexuality, eating, substance use, and recreational practices like gaming or gambling. Certain practices can be framed as mental illnesses or disorders based on classifications of normality, like the DSM. The manual is widely used as a diagnostic reference worldwide (Marecek & Hare-Mustin, 2009; Marecek & LaFrance, 2021). It provides standard criteria for diagnosing mental health conditions.

The DSM can also reinforce the medicalisation of human distress by framing a wide range of emotional and psychological experiences as disorders. This solidifies a biomedical approach to mental health, often sidelining alternative understandings such as the role of socio-cultural or environmental factors (e.g., unemployment due to financial crises) in causing distress and a sense of helplessness (Riddle, 2024). In this way, psychiatry and psychology may play powerful roles in the medicalisation process and the social control of deviation according to legal, moral, and even religious norms (Marecek & Lafrance, 2021).

The advantages and disadvantages of medicalisation

The medicalisation of various aspects of life has both advantages and disadvantages. There are, on one hand, arguable benefits to medicalising some issues. This was highlighted in Conrad’s (1975, p. 18) foundational work in the 1970s:

Clearly there are some real humanitarian benefits to be gained by such a medical conceptualization of deviant behaviour. There is less condemnation of the deviants (they have an illness, it is not their fault) and perhaps less social stigma. In some cases, even the medical treatment itself is more humanitarian social control than the criminal justice system.

Conrad refers to the conceptual shift from badness to sickness (in Table 2.3.1), arguing that being diagnosed as ill rather than socially deviant may allow a more sympathetic response from others, including healthcare providers. This may be especially so when a condition or disorder is seen as outside of individual control, as in the reframing of socially unacceptable behaviours such as frequent intoxication as an addiction and disruptive behaviour as hyperactivity. Medicine may also offer tangible, sometimes straightforward, and more affordable solutions for complex problems (Schmidt, 2011).

As discussed earlier, receiving a medical diagnosis may allow people to take up the sick role and any advantages attached to it. A good example is the medicalisation of problems of living (as in Table 3.2.1). For instance: working-class Brazilian women use the idea of “suffering from nerves” to explain troubles—like worry, sadness, and sleeplessness—that stem from precarious living conditions. The subsequent diagnosis of “nerves illness” frames these troubles as a medical issue rather than a socio-economic one. This medical label allows them to evade the social stigma associated with poverty as well as potentially giving access to resources and care they might not otherwise have received.

This brings us to one of the primary disadvantages of medicalisation: focusing on the individual. In the case of “suffering from nerves,” women may receive medical treatment and support. However, the root causes of their suffering (economic inequity, lack of state support) remain unchanged (Traverso-Yépez & De Medeiros, 2005). The issue is that “framing suffering in psychiatric terms may depoliticise problems by individualising and disconnecting suffering from the contexts in which it has arisen and is maintained” (Degerman, 2020, p. 1010). Instead, everyone is treated individually and tasked with taking personal control of their own wellbeing, without attempts to improve social conditions that cause suffering (Anleu, 2019).

Treatment often involves medication, an attractive and simple solution in the form of “a pill for every ill”. Medication may offer many sufferers relief and treatment options. Still, it can lead to an overreliance on pharmacological treatment for difficulties whose origins and alleviation may be better understood as societal rather than individual. Moreover, medications themselves are also not always risk-free (Moynihan, Doust, & Henry, 2012). In this way, medicalisation is supported by healthism with its emphasis on individual responsibility for health and the pursuit of health as a primary value (Crawford, 1980; 2006; see Chapter 1.4).

Another important concern related to medicalisation, also noted above, is that of social control. The ever-widening authority and influence of psycho-medicine grants authority over more parts of people’s lives. Medical professionals have increasingly been tasked with applying mechanisms of social control by treating deviance from dominant societal expectations of how certain people ought to behave (as we saw above in the vivid example of the enforced psychiatric treatment of women protesters in Iran). Their job is to induce conformity with agreed social norms or at least help to minimise or manage behaviour portrayed as deviant, be it a disruption of the social order, violation of appearance-related norms, or other kinds of disruptive, unacceptable, or supposedly immoral behaviours (Anleu, 2019).

This process is known as the “medicalisation of deviance” (or the “medicalisation of social ills”), which can mask moral judgements behind the façade of epidemiological and scientific evidence (Barker, 2010; Heally-Cullen et al., 2024). Practices previously considered simply as morally inappropriate or “bad” (but at some point, within the range of normality) are reclassified as sickness: the conceptual shift from badness to madness (as referred to in Table 3.2.1).

The relatively recent concept of “addiction” provides a familiar illustration of the medicalisation of deviance. The emergence of this diagnostic label highlights how certain morally controversial or unacceptable behaviours are reframed in pathological terms rather than as (primarily) sinful, illegal, or immoral. Hence, sexual activity or alcohol and drug use that is considered excessive is diagnosed as sex addiction, alcoholism, and drug addiction respectively. The socially undesirable behaviour moves from being understood (primarily) as moral issue (sin or crime) to a medical one (illness, condition).

Moreover, according to each framing of the issue, the behaviour is differently controlled: through moral sanction (e.g., excommunication from church, gossip), legal punishment (e.g., imprisonment, hard labour, fines), or psycho-medical expertise (e.g., institutionalisation, medications, therapy). Nevertheless, each is a form of social control through different means (Heally-Cullen et al., 2024). Where before religious or legal authorities were granted authority over certain social matters (like sex or alcohol consumption), medicalisation now brings them under the authority of healthcare professionals tasked with their management (Anleu, 2019). Relabelling an issue as a health issue rather than a moral one, as in the case of addiction, may remove some of the (overt) stigma associated with it by freeing the person from moral blame. However, being labelled as ill or deviant may bring a different set of (less overt) social judgements (Marecek & Hare-Mustin, 2009).

Attending to the social process of medicalisation raises critical questions about the role of medicine in society, the nature of health and illness, and the balance between medical authority and individual experience. As such, it is essential to understand diagnosis not just as a medical act, but also as a complex social and political phenomenon. Designating signs as indicative of disease involves interpretation. This is more than a matter of individual judgment; it involves others. Presenting symptoms constitutes a moral claim to be treated in a certain way by others, both laypeople and professionals. In the following chapter, we explore how this plays out in interactions with healthcare providers specifically, where a key issue is power, primarily associated with knowledge and expertise. (See Chapter 1.4).

Sexual desire is not simply biological; it is a complex, socially located experience shaped by cultural and gendered norms. Yet the process of medicalisation reduces sexual desire to a set of simple physiological responses. By focusing on quantifying and measuring desire, medicalisation neglects the context in which desire is experienced, treating it as an objective “thing” rather than a culturally constructed phenomenon (Vares & Braun, 2006). Male sexual desire is culturally well understood—men are expected to be virile and always-desiring, with Viagra even used to enhance performance (Vares & Braun, 2006). In contrast, female desire has long been seen as physiologically complex, “hard-to-know,” and variable (Fahs, 2016). Historically, Western medicine has classified women’s sexuality as irregular or deviant (Potts, 2008), arguing that female sexual desire requires control according to the norms and ideals of the time. Medical “experts” turned their gaze on female sexuality, framing it as something to be pathologised and treated objectively (Bancroft, 2002).

Under the “medical gaze” (Foucault, 1963/2003), female sexual desire is managed and regulated in the name of helping women address “problems” with desire (Moynihan & Mintzes, 2010). Diagnoses such as hysteria, nymphomania, and, more recently, female sexual dysfunction are based on dominant societal norms regarding gender and sexuality—that is, on ideals about how women should behave. For instance, Victorian society deemed women should be sexually modest and passive, and those with “excessive” libido could be diagnosed with female hysteria (Jutel & Mintzes, 2018). Similarly, in the late 19th century, nymphomania was recognised as a mental illness in Europe and North America. It was applied to women who exhibited “too much” sexual desire through fantasies, masturbation, or expressing a higher sexual appetite than their husbands (Marecek & LaFrance, 2021).

Today, in Europe and North America, a woman displaying more sexual desire than a man is less likely to be pathologised, but the opposite. Changes in gender norms now render low sexual desire problematic. The development of Masters and Johnson’s human sexual response cycle contributed to the view that women with comparatively low sexual drive are disordered (Potts, 2008). Consequently, variable or low sexual desire may be diagnosed as female sexual dysfunction—specifically as female orgasmic disorder or female sexual interest/arousal disorder—and treated pharmaceutically (Potts, 2008; Thomas & Gurevich, 2021).

These conditions are rooted in subjective judgments about what counts as “excessive” or “insufficient” desire for women, based on prevailing values and the patriarchy. Medicalisation, therefore, works to pathologise deviations from societal norms and serves to control women’s expression of desire—and by extension, their sexuality and bodies—in the interests of the patriarchy (Thomas & Gurevich, 2021).

In contemporary Western contexts, women’s desire is negotiated within a double bind. They are expected to embody purity while also being sexually available—“up for it” but not labelled promiscuous (Farvid & Braun, 2014). This contradictory expectation makes the notion of “normal” female sexual desire elusive. Capitalist economies exploit these conflicting discourses, encouraging women to pay for pharmaceutical “fixes” without acknowledging the culturally specific reasons for fluctuations in desire. The creation of medications for variations in desire reinforces the notion that such variations are pathologies needing pharmaceutical solutions (Bancroft, 2002).

“Pink Viagra”

So-called Pink Viagra is an example of how a disorder called female sexual dysfunction was constructed by researchers and pharmaceutical companies to market medication as a treatment—what Leonore Tiefer describes as a “textbook case of disease mongering” (Tiefer, 2006, p. 436). The origins of female sexual dysfunction as a disorder are tied to the success of Viagra (sildenafil), approved in 1998 for treating erectile dysfunction in men (Hartley, 2006; Moynihan, 2003). Pharmaceutical companies then sought a similar treatment for women. However, unlike erectile dysfunction, there is no clear physiological condition equivalent for women. In the late 1990s, drug company-sponsored meetings and conferences brought together clinicians, researchers, and industry representatives to define female sexual dysfunction as a medical condition. Diagnostic criteria for female sexual dysfunction—such as low sexual desire, arousal difficulties, and challenges achieving orgasm—began appearing in medical journals, framing female desire firmly within a biological model (Tiefer, 2002).

The quest for “Pink Viagra” has been fraught with challenges. Female sexual dysfunction is difficult to measure and define, and its treatment has faced significant criticism. Flibanserin, the first drug approved to treat low sexual desire in women, has been criticised for safety concerns, side effects, and modest efficacy. Unlike Viagra, which targets a clear physiological mechanism, Flibanserin’s effectiveness relies mainly on self-reported measures of desire, and clinical trials have not consistently shown a tangible benefit over placebo (Jutel & Mintzes, 2018).

It is also important to note that female sexual dysfunction is not applied uniformly across all women. The diagnosis primarily targets cisgender, heterosexual women, thereby erasing the experiences of those of other sexualities and genders. Moreover, female sexual dysfunction is largely a condition affecting White women who have the resources, such as health insurance, to access specialised care (Battle et al., 2022). In contrast, women of colour, particularly Black and Asian women, often face the dual challenges of the medicalisation of their sexuality and societal hypersexualisation based on racialised stereotypes (Pires, 2024; Sanger, 2009).

The consequences of medicalising female sexual desire

The medicalisation of women’s sexuality and desire frames variations in desire as pathologies that require pharmaceutical solutions (Bancroft, 2002). This framing influences how women understand and experience their sexuality—prompting questions of whether they are “normal” or in need of corrective measures. Advertisers and the media capitalise on these concerns, fuelling the anxiety that underpins medicalisation (Cassells, 2008; Germov & Freij, 2019).

While pharmaceutical companies profit from narrow standards of normalcy, women do not benefit when these standards are divorced from their social context. The medicalisation of desire emphasises a “normal” sexual function, imposing strict expectations on women and risking the stigmatisation of the full spectrum of sexual desire. Critical scholars argue that these normative standards are rooted in androcentric views, reducing sexual pleasure solely to genital function and leaving little room for other forms of desire or the choice to abstain (Tiefer, 2001).

These critiques do not deny that biological factors can influence sexual desire. Rather, critical health researchers contend that treating desire as a solely isolated physiological problem is reductionist and yields limited solutions. Flibanserin’s modest efficacy illustrates that addressing sexual desire without considering its broader context can lead to ineffective or problematic outcomes. Instead, proponents argue for a psychosocial view of sexual desire that acknowledges its contextual nature, suggesting that “sexual life is contextualized for everyone” (Tiefer, 2004, p. 273). Thus, while physiological factors may contribute to sexual issues, they are only one aspect of a complex picture (Hartley, 2006; Potts, 2008; Tiefer, 2001).

Pharmacological responses marketed as “for women” can also marginalise other research agendas that might genuinely support women’s sexual and reproductive health. From a critical feminist perspective, the normalising agenda of female sexual dysfunction ultimately limits women’s sexual agency and reinforces problematic cultural expectations surrounding “normal” sexuality.

The example of female sexual dysfunction highlights why critical health psychologists remain vigilant regarding the disciplinary power of medicalisation in labelling female desire as “dysfunction” (see Chapter 1.2 and Chapter 2.3 on power). The medicalisation of female desire is intertwined with societal norms, gendered expectations, and the capitalist motives of pharmaceutical companies that profit from pathologising and “treating” desire. Critical health psychology is well placed to question this process, as it recognises that health and sexuality are socially constructed and advocates for perspectives that honour the diverse experiences of desire beyond biomedical models. Feminist scholars, in particular, emphasise that desire—in all its variations—must be understood as part of a spectrum of socially produced experiences rather than merely a symptom of dysfunction.

Conclusion

Many critiques of diagnostic frameworks centre on their failure to address the social determinants of health, such as poverty, discrimination, and environmental factors. By focusing narrowly on individual pathology, diagnostic systems can obscure the broader social conditions contributing to illness and suffering. For instance, the medicalisation of mental health often overlooks the structural inequalities—such as racism, sexism, or economic deprivation—that underlie psychological distress. Critics argue that this narrow focus reinforces systemic inequalities, diverting attention from the need for broader social change. In this sense, diagnostic systems can perpetuate injustice by framing health issues as individual problems rather than societal ones (Marecek & LaFrance, 2021). Such a sustained focus also benefits those with economic and political interests in preserving the status quo.

Despite the various critiques of the biomedical model of diagnosis, it remains deeply entrenched in both medical practice and public understanding. The authority of diagnosis continues to shape clinical encounters, with doctors relying on established diagnostic categories to guide treatment. The public, too, often looks to medical diagnoses as authoritative explanations for their health conditions, reinforcing the power of the biomedical approach. This authority persists even in the face of growing awareness of the limitations of purely biomedical explanations of health, such as their tendency to overlook social and environmental factors. As a result, diagnosis remains a powerful tool that shapes not only medical practice but societal understandings of health and illness.

Summary of main points

-

Diagnosis as a social practice

Diagnosis is not merely about labelling diseases; it establishes a shared understanding of what constitutes sickness, shaped by values, norms, and biology (Jutel, 2024).

-

An interpretative and power-laden process

Diagnosis involves assigning clinical observations and patient experiences to predefined categories—a process imbued with judgments about normality and abnormality, reflecting specialist knowledge and power dynamics (Durie, 2003; Rose, 2013).

-

Benefits and drawbacks

- Provides access to treatment, resources, and a standard language for medical communication

- Can reduce complex, personal experiences to oversimplified labels, potentially leading to stigma, reduced social roles, and neglect of broader contextual factors (Dumit, 2006; Ward, 2019)

-

Diagnostic classification as interpretative

Although diagnostic categories are often seen as objective, they are the result of human judgment and consensus among experts, reflecting socio-political currents rather than pure biological facts (Bourdieu, 1991; Jutel, 2021).

-

The role of values and norms

The creation of diagnostic categories is embedded within cultural contexts, where shifting societal values (e.g., around gender, race, and sexuality) influence what is considered “normal” or pathological. Historical examples (drapetomania and the pathologisation of homosexuality) illustrate this dynamic (Marecek & Lafrance, 2021; Tyson, 2011).

-

Diagnosis in healthcare interactions

Diagnosis structures the doctor–patient relationship by creating a knowledge hierarchy that privileges biomedical knowledge over lay or experiential knowledge, often marginalising patient perspectives and reinforcing power imbalances (Dumez & L’Espérance, 2024; Mishler, 1986).

-

Broader socio-political implications

Beyond individual treatment, diagnosis plays a crucial role in legal decisions, public health planning, resource allocation, and social control, determining who is granted the “sick role” and access to social goods (Dumit, 2006; Nettleton, 2006).

-

Medicalisation as a process

Medicalisation reframes everyday experiences as medical issues, driven by economic interests and the machinery of healthcare. While it can humanise deviant behaviour by framing it as illness (thereby reducing blame), it also risks overemphasising individual responsibility and obscuring structural causes (Conrad, 1975; Dew et al., 2016).

-

The medicalisation of female desire (case study)

The pathologisation of women’s sexual desire (e.g., diagnoses of female sexual dysfunction) illustrates how societal norms, gendered expectations, and capitalist motives drive the medicalisation process. This results in the marketing of drugs like Flibanserin (“Pink Viagra”), which have been critiqued for their modest efficacy and safety concerns (Jutel & Mintzes, 2018; Tiefer, 2006).

-

The double-edged nature of diagnosis:

Diagnostic labels can validate and provide a roadmap for treatment, yet they also have profound social, psychological, and material consequences—shaping personal identity, social roles, and reinforcing both stigma and social control.

Learn more

Weblog

- The companion blogs Mad in the UK and Mad in America publish some thought-provoking posts, like Cromby’s (2025) below.

Blog Posts

- Cromby, J. (2025). What if being miserable isn’t an illness? [Weblog post]. Mad in the UK. Retrieved February 2025, from https://www.madintheuk.com/2025/02/what-if-being-miserable-isnt-an-illness/

- Jutel, A. (2022) The social life of diagnosis [Weblog post]. MJA InSight, Available from https://insightplus.mja.com.au/2022/13/the-social-life-of-diagnosis/

Journal Special Issue

- The Journal of Sex Research published a special issue on the Medicalisation of Sex.

Video

- Too much medicine, TEDx Talk by Ray Moynihan “a researcher, writer and award-winning journalist. The author of four books on the business of medicine, Ray has an international reputation for investigating the corrupting influences within health systems. He’s currently a columnist for the BMJ and undertaking a PhD on how to prevent the modern epidemic of over-diagnosis.”

- Orgasm Inc.: The strange science of female pleasure (2009) documentary on the medicalisation of “female sexual dysfunction” (available on demand): “ORGASM INC. is a powerful look inside the medical industry and the marketing campaigns that are literally and figuratively reshaping our everyday lives around health, illness, desire — and that ultimate moment: orgasm.”

References

Aronowitz, R. A. (2001). When do symptoms become a disease? Annals of internal medicine, 134(9.2), 803–808. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-134-9_Part_2-200105011-00002

Blaxter, M. (1978). Diagnosis as category and process: The case of alcoholism. Social Science and Medicine, 12, 9–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/0271-7123(78)90017-2

Böhmke, W., & Tlali, T. (2008). Bodies and behaviour: Science, psychology and politics. In C. Van Ommen & D. Painter (Eds.), Interiors: A history of psychology in South Africa (pp. 125–151). Unisa Press.

Bonnie, R. J. (2002). Political abuse of psychiatry in the Soviet Union and in China: Complexities and controversies. The Journal of the American Academy of Psychiatry and the Law, 30, 136–144. https://ssrn.com/abstract=1760001

Boulton, T. (2019). Nothing and everything: Fibromyalgia as a diagnosis of exclusion and inclusion. Qualitative Health Research, 29(6), 809–819. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732318804509

Bourdieu, P. (1991). The peculiar history of scientific reason. Sociological Forum, 6, 3–26. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01112725

Brown, P. (1995). Naming and framing: The social construction of diagnosis and illness. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 34–52. https://doi.org/10.2307/2626956

Brown, P., Morello-Frosch, R., Zavestoski, S., & the Contested Illnesses Research Group. (2012). Contested illnesses: Citizens, science, and health social movements. University of California Press.

Cacchioni, T., & Tiefer, L. (2012). Why medicalization? Introduction to the special issue on the medicalization of sex. The Journal of Sex Research, 49(4), 307–310. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224499.2012.690112

Campbell, C. (2004). The role of collective action in the prevention of HIV/Aids in South Africa. In D. Hook (Ed.), Critical psychology (pp. 335–359). UCT Press.

Denny, E. (2009). “I never know from one day to another how I will feel”: Pain and uncertainty in women with endometriosis. Qualitative Health Research, 19(7), 985–995. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732309338725

Drescher, J. (2015). Out of DSM: Depathologizing homosexuality. Behavioral Sciences, 5(4), 565–575. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs5040565

Dumez, V., & L’Espérance, A. (2024). Beyond experiential knowledge: A classification of patient knowledge. Social Theory & Health, 22, 173–186. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41285-024-00208-3

Durie, M. (2004). Understanding health and illness: Research at the interface between science and indigenous knowledge. International Journal of Epidemiology, 33(5), 1138–1143. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyh250

Engebretsen, K. M., & Bjorbækmo, W. S. (2019). Naked in the eyes of the public: A phenomenological study of the lived experience of suffering from burnout while waiting for recognition to be ill. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 25(6), 1017–1026. https://doi.org/10.1111/jep.13244

Fielding-Singh, P., & Dmowska, A. (2022). Obstetric gaslighting and the denial of mothers’ realities. Social Science & Medicine, 301, 114938. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.114938

Foucault, M. (1967/2002). The birth of the clinic. Routledge.

Gay & Lesbian Alliance Against Defamation (2022) 2022 State of HIV stigma. https://glaad.org/endhivstigma/2022/#:~:text=The State of HIV Stigma study shows a majority of,know a little about HIV

Germov, J., & Freij, M. (2019). Media and health: Moral panics, miracles and medicalisation. In J. Germov (Ed.), Second opinion: An introduction to health sociology (pp. 422–445). Oxford University Press.

Gibson, A. F., Broom, A., Kirby, E., Wyld, D. K., & Lwin, Z. (2017). The social reception of women with cancer. Qualitative Health Research, 27(7), 983–993. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732316637591

Hartley, H. (2006). The ‘pinking’ of Viagra culture: Drug industry efforts to create and repackage sex drugs for women. Sexualities, 9(3), 363–378. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363460706065058

Hook, D. (2004). Frantz Fanon, Steve Biko, ‘psychopolitics’, and critical psychology. In D. Hook (Ed.), Critical psychology (pp. 84–114). UCT Press.

Hooshyari, L. (2024). Psychology as an oppressive tool during the ‘Woman, Life, Freedom’ uprising in Iran. Annual Review of Critical Psychology, 18, 1089–1104. https://discourseunit.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/1089_hooshyari.pdf [PDF]

Horton-Selway, M. (2018). The discourse of ADHD: Perspectives on attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Cham Springer International.

Hudson, N. (2022). The missed disease? Endometriosis as an example of ‘undone science’. Reproductive Biomedicine & Society Online, 14, 20–27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rbms.2021.07.003

Jutel, A. (2011). Classification, disease, and diagnosis. Perspectives in Biology and Medicine, 54(2), 189–205. https://doi.org/10.1353/pbm.2011.0015

Jutel, A. (2024). Putting a name to it: Diagnosis in contemporary society. Johns Hopkins University Press.

Lafrance, M. N., & McKenzie-Mohr, S. (2013). The DSM and its lure of legitimacy. Feminism & Psychology, 23(1), 119–140. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959353512467974

Mengshoel, A. M., & Heggen, K. (2004). Recovery from fibromyalgia – previous patients’ own experiences. Disability and Rehabilitation, 26(1), 46–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/09638280410001645085

Mik-Meyer, N. (2011). On being credibly ill: Class and gender in illness stories among welfare officers and clients with medically unexplained symptoms. Health Sociology Review, 20(1), 28–40. https://doi.org/10.5172/hesr.2011.20.1.28

Morison, T., Ndabula, Y., & Macleod, C. I. (2022). The contraceptive paradox, contraceptive agency, and reproductive justice: Women’s decision-making about long-acting reversible contraception. In T. Morison & J. M. J. Mavuso (Eds.), Sexual and reproductive justice: From the margins to the centre (pp. 227–246). Lexington Books.

Moynihan, R. (2010). Merging of marketing and medical science: Female sexual dysfunction. BMJ, 341, c5050. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.c5050

Moynihan, R., Albarqouni, L., Nangla, C., Dunn, A. G., Lexchin, J., & Bero, L. (2020). Financial ties between leaders of influential US professional medical associations and industry: Cross sectional study. BMJ, 369, m1505. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m1505

Moynihan, R., Doust, J., & Henry, D. (2012). Preventing overdiagnosis: How to stop harming the healthy. BMJ, 344, e3502. https://www.bmj.com/content/bmj/344/bmj.e3502.full.pdf [PDF]

Moynihan, R., Lai, A., Jarvis, H., Duggan, G., Goodrick, S., Beller, E., & Bero, L. (2019). Undisclosed financial ties between guideline writers and pharmaceutical companies: A cross-sectional study across 10 disease categories. BMJ Open, 9(2), e025864. https://bmjopen.bmj.com/content/9/2/e025864

Murphy, M., Kontos, N., & Freudenreich, O. (2016). Electronic support groups: An open line of communication in contested illness. Psychosomatics, 57(6), 547–555. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psym.2016.04.006

Nielsen, M. (2018). Experience and explanation of AHHD. Routledge.

Parker, I., Georgaca, E., Harper, D., McLaughlin, T., & Stowell-Smith, M. (1996). Deconstructing psychopathology. Sage.

Penney, L., Barnes, H. M., & McCreanor, T. (2011). The blame game: Constructions of Māori medical compliance. AlterNative, 7(2), 73–86. https://doi.org/10.1177/117718011100700201

Pheby, D. F. H., Araja, D., Berkis, U., Brenna, E., Cullinan, J., de Korwin, J-D., Gitto, L., Hughes, D. A., Hunter, R. M., Trepel, D., & Wang-Steverding, X. (2020). The development of a consistent Europe-wide approach to investigating the economic impact of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis (ME/CFS): A report from the European Network on ME/CFS (EUROMENE). Healthcare, 8(2), 88. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare8020088

Riessman, C. K. (2015). Ruptures and sutures: Time, audience and identity in an illness narrative. Sociology of Health & Illness, 37(7), 1055–1071. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.12281

Rossen, C. B., Buus, N., Stenager, E., & Stenager, E. (2019). Identity work and illness careers of patients with medically unexplained symptoms. Health, 23(5), 551–567. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363459317739440

Rosenberg, C. E. (2002). The tyranny of diagnosis: Specific entities and individual experience. The Milbank Quarterly, 80(2), 237–260. https://doi.org/10.1111/1468-0009.t01-1-00003

Shefer, T. (2004). Psychology and the regulation of gender. In D. Hook (Ed.), Critical psychology (pp. 187–209). UCT Press.

Shorter, E. (1997). A history of psychiatry: From the era of the asylum to the age of Prozac. Wiley.

Smail, D. (2005). Power, interest and psychology: Elements of a social materialist understanding of distress. PCCS Books.

Thomas, F. (2021). Medicalisation. In K. Chamberlain & A. C. Lyons (Eds.), International handbook of critical issues in health and illness (pp. 23–33). Routledge.

Tiefer, L. (2001). The selling of ‘female sexual dysfunction’. Journal of Sex & Marital Therapy, 27(5), 625–628. https://doi.org/10.1080/713846822

Tiefer, L. (2004). Sex is not a natural act & other essays. Westview Press.

Tiefer, L. (2006). Female sexual dysfunction: A case study of disease mongering and activist resistance. PLoS Medicine, 3(4), e178. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.0030178

Tiefer, L. (2008). Female genital cosmetic surgery: Freakish or inevitable? Analysis from medical marketing, bioethics, and feminist theory. Feminism & Psychology, 18(4), 466–479. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959353508095529

Tuffin, K. (2017). Prejudice. In B. Gough (Ed.), The Palgrave handbook of critical social psychology (pp. 319–344). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-51018-1_16

Tyson, P. J. (2011). Psychology and mental health. In P. J. Tyson, D. Jones, & J. Elcock (Eds.), Psychology in social context: Issues and debates (pp. 156–172). John Wiley & Sons.

ViiV Healthcare. (2025). An insight into organisational HIV stigma and discrimination. https://viivhealthcare.com/ending-hiv/stories/positive-perspectives/organisational-hiv-stigma/#1

Walker, H. K. (1990) The origins of the history and physical examination. In H. K. Walker, W. Dallas Hall, & J. Willis Hurst (Eds.), Clinical methods: The history, physical, and laboratory examinations (3rd ed.). Butterworths.

Ward, C. D. (2019). Between sickness and health: The landscape of illness and wellness. Routledge.