3.1 Frameworks for critical health psychology practice in Aotearoa

Gloria Fraser and Alex Walker

Overview

Practitioners of critical health psychology work in a range of settings, including in health services as registered psychologists; as members of the broader wellbeing workforce; in health promotion, public health, and policy; in non-governmental and community health organisations; and in research and teaching. “Psychologist” is a protected title in Aotearoa (meaning only those who are registered with the New Zealand Psychologists Board can use this term to describe themselves; Health Practitioners Competence Assurance Act 2003). Here, we use “practitioners of critical health psychology” to emphasise that professional registration is just one pathway to practice in our diverse field.

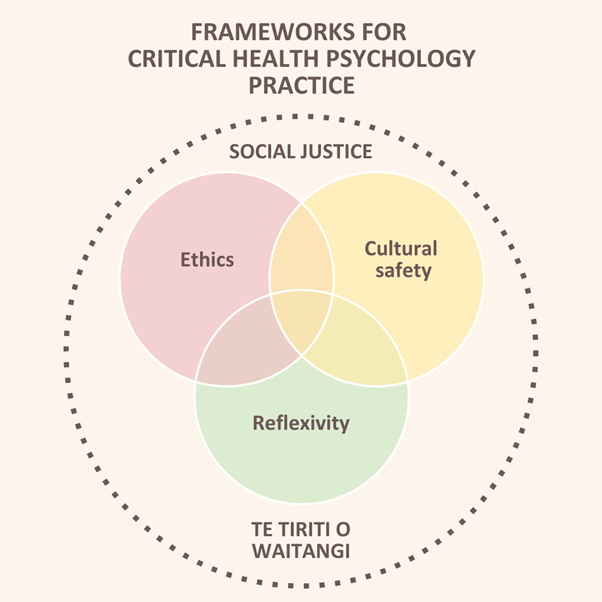

In this chapter, we present an overview of ethics, cultural safety, and reflexivity as frameworks to guide emerging practitioners in the discipline of critical health psychology. These frameworks are grounded in Te Tiriti o Waitangi and sit within a broader frame of social justice. Figure 3.1.1 illustrates the interconnected nature of these frameworks, which practitioners must understand and apply in relation to one another.[1]

Learning objectives

This chapter addresses the following learning objectives:

- Articulate the significance of Te Tiriti o Waitangi for critical health psychology practice.

- Describe critical reflexivity and the relationship between reflexivity and action.

- Understand how the psychologists’ Code of Ethics principles can be used to guide decision making in critical health psychology practice.

- Describe cultural safety and distinguish between cultural appropriation and cultural engagement.

Putting the ‘critical’ in critical health psychology practice

Health psychology as a discipline explores how psychological knowledge and ways of working contribute to understanding the development and maintenance of health and illness, the relationship between health and illness, and the interaction of mind, body, and sociocultural determinants of health (Chamberlain & Murray, 2009; Matarazzo, 1980; Snooks, 2009). Critical health psychology does this with a particular focus on issues of power, equity, and benefit, asking: What definition of health and illness are we using? Who benefits from dominant discourses around health, and who is harmed? Who gets to access “healthy”, and who is excluded? Who is blamed for ill health? As Chamberlain et al. (2018) note, “critical scholars are therefore concerned to ensure the application of knowledge for the benefit of society, often with a particular concern for the oppressed and disadvantaged, and with a strong agenda for social justice” (p. 457).

Practitioners of critical health psychology question the individualism often associated with mainstream health psychology; that is, the tendency to assign responsibility for promoting wellbeing and preventing ill health to individuals, and to understand psychologists as expert, objective practitioners using technical solutions to solve functional problems (Bolam & Chamberlain, 2003). However, we should not confuse an individualistic approach with working with individuals. Prilleltensky and Prilleltensky (2003) propose that the values, assumptions, and practices of professional helpers (who might work at the individual, whānau, or community level) can work in synergy with those of critical agents of social change to promote both wellness and liberation. To realise the goals of critical health psychology “we need specialized knowledge as much as political knowledge, ameliorative therapies as much as social change, and people working inside the system as much as people confronting it” (Prilleltensky & Prilleltensky, 2003, p. 246). In other words, we can take a critical perspective regardless of where in health systems and settings we practice.

As you read this chapter, we invite you to consider your spheres of influence, both personally and professionally: the places and spaces where you can enact transformative change. It can often feel as if we lack the power to challenge unjust systems that maintain health inequities—particularly for those of us early in our career. However, change is created incrementally, and small actions can have ripple effects. Think about the conversations about the ethical, sociocultural, and political aspects of health psychology that you have with whānau, friends, teachers, colleagues, tāngata whai ora, and others in your community. At the dinner table, at the bar, and in the therapy room. We also note that practitioners of critical health psychology must, at times, pick their battles. The pursuit of social justice and health equity takes time and energy, and we encourage readers to consider when to agitate for change, and when to rest and conserve energy.

Te Tiriti o Waitangi

Te Tiriti o Waitangi is a foundational document in Aotearoa New Zealand, and a foundational framework for practitioners of critical health psychology in the pursuit of social justice and health equity. The Code of Ethics for psychologists working in Aotearoa (discussed further in the next section) includes a preamble declaring that “there shall be due regard for… the provisions of, and the spirit and intent of, the Treaty of Waitangi” (Code of Ethics Review Group, 2002, p. 1); the Core Competencies for the practice of psychology in Aotearoa notes that practitioners of psychology must be Te Tiriti “partners” (New Zealand Psychologists Board, 2018, p. 6); and all Crown-funded health providers are obligated to uphold Te Tiriti to achieve better health outcomes for Māori (Ministry of Health, 2024). Despite promises to uphold Te Tiriti obligations throughout health legislation, policies, and frameworks, Te Tiriti o Waitangi breaches continue at all levels of the health system (Came-Friar et al., 2019).

Here, we provide a brief history of Te Tiriti o Waitangi, as well as guidance on further reading for Te Tiriti conscientisation and deep learning (see Mutu, et al., 2021). We draw on Freire’s (2000) definition of conscientisation as “learning to perceive social, political, and economic contradictions, and to take action against the oppressive elements of reality” (p. 35). Understanding the historical and contemporary context of Te Tiriti o Waitangi is essential for developing a Te Tiriti analysis for use in critical health psychology practice.

Te Tiriti o Waitangi: a brief history

Te Tiriti o Waitangi is an agreement between Māori rangatira and representatives of the British Crown, first signed on 6 February 1840. It was created with the intention of establishing a British Governor in New Zealand, confirming Māori authority and ownership over their land, homes, and treasures (including spirituality and knowledge systems), and ensuring Māori had the same rights and privileges as British subjects (Mutu, 2018). There are two treaty texts—ostensibly different language versions of the same document—however, the te reo Māori text (Te Tiriti o Waitangi) is not a translation of the English language text (The Treaty of Waitangi). Differences between the texts are widely understood as driving conflict between Māori and the Crown, however we challenge this framing. We contend that it is breaches of both treaties (i.e., widespread land confiscation and violent suppression of Māori language and culture) that have created a legacy of racism and health inequities in Aotearoa and had disastrous impacts on Māori wellbeing (Brown & Bryder, 2023; Came-Friar et al., 2019; Reid, 2019).

Myths (here meaning false but widely held ideas) abound about Te Tiriti o Waitangi, including that Māori voluntarily ceded sovereignty, did not understand the meaning of the document they signed, and that differences between the text were a result of rushed translation (see Burns et al., 2024; McCreanor et al., 2024, for discussion of how treaty myths are perpetuated through historical and educational texts). Analysis from the Waitangi Tribunal (a permanent commission of inquiry established in 1975 to investigate Treaty breaches) concluded that rangatira who signed Te Tiriti o Waitangi in 1840 did not cede their sovereignty (Waitangi Tribunal, 2014), and Jackson (2019) notes that the idea that Māori ceded sovereignty “requires a profound suspension of disbelief” (para. 29). Te Tiriti includes a provision for the British Crown to govern British subjects wherever they are in Aotearoa (kāwanatanga) and reaffirms Māori tino rangatiratanga. As such, Māori agreed to a relationship with the British Crown, with each (Māori rangatira and the British Governor) holding different roles and spheres of influence.

Over the last 50 years the Crown has adopted a “principles-based” approach, to establish a “middle ground” between the two treaty texts (Burns et al., 2024). These are intended to capture the “spirit and intent of the Treaty” (Ludbrook, 2015, p. 3), however, various lists of treaty “principles” created by Crown agencies (e.g., partnership, protection, and participation; Royal Commission on Social Policy, 1988) are open to interpretation and, at times, conflict with one another (Burns et al., 2024). Tiriti scholars contend that treaty principles “effectively reinterpret Te Tiriti in favour of Pākehā” (Came & McCreanor, 2015, p. 28), and have limited engagement with Te Tiriti o Waitangi. The reliance on these principles also diminishes the status of Te Tiriti o Waitangi as the primary text. Legal frameworks, such as the principle of contra proferentem, which resolves ambiguities in favour of the party that did not draft the agreement, further support privileging Te Tiriti (Burns et al., 2024).

We advocate an article-based or provisions-based approach, which privileges Te Tiriti o Waitangi as the authoritative text and focuses on what was written in this text. Through Te Tiriti conscientisiation, practitioners of critical health psychology can develop their Te Tiriti analysis, and, in turn, an ability to take health action grounded in the text of Te Tiriti o Waitangi. Textbox 1 presents an overview of what practitioners of critical health psychology must know about Te Tiriti o Waitangi, to support the development of their Te Tiriti analysis skills.

Textbox 1. Te Tiriti o Waitangi: What practitioners of critical health psychology should understand and explore

Te Tiriti o Waitangi is often portrayed as a historic text, however, we understand it as a living document: new Te Tiriti analysis, evidence, and insights are regularly published (see, for example, the Waitangi Tribunal’s Te Paparahi o Te Raki reports, 2014, 2022). Practitioners of critical health psychology must consider Tiriti conscientisiation (or critical consciousness) as an ongoing and iterative process. Here, we propose immediate learning priorities for practitioners of critical health psychology, as well as lifetime learning. To support this learning, we strongly recommend practitioners of critical health psychology attend Te Tiriti o Waitangi training and engage with the recommended reading list of Tiriti resources found at the end of this chapter. These learning priorities are based in the guidance of political education collective Te Atakura (Society for Conscientisation).

As immediate learning priorities, practitioners of critical health psychology should understand:

- Māori society prior to European arrival as fully formed, with a long history of treaty-making, and governed by cultural concepts and practices (tikanga, kawa, mana, tapu, and noa).

- the role of the Doctrine of Discovery in sanctioning colonisation and colonial violence.

- the relationship between He WhakaputangaHe Whakaputanga o te Rangatiranga o Nu Tireni (He Whakaputanga) and Te Tiriti o Waitangi.

- the circumstances prompting the development of a treaty, including British lawlessness, international interest in Aotearoa, and the threat of New Zealand Company land speculators.

For lifetime learning, practitioners of critical health psychology should explore:

Te Tiriti o Waitangi and critical health psychology practice

Psychology in Aotearoa New Zealand (including critical health psychology) has its roots in Western thought, and a history of devaluing and disregarding Indigenous psychologies (Kennedy et al., 2022; Waitoki et al., 2024a). Failing to acknowledge the contribution of mātauranga Māori (Māori knowledges) in psychological theory and practice breaches Article Two of Te Tiriti o Waitangi, which promises “te tino rangatiratanga o o ratou … taonga katoa” (full exclusive and undisturbed possession of their treasures), including Māori healing and wellbeing practices. Importantly, psychology in Aotearoa New Zealand also has a history of strong Māori resistance to racism and epistemic violence, as evidenced by decades of work by Māori psychology, psychiatry, and health scholars (see Bennett et al., 2014; Cherrington, 2003; Durie, 1994; Lawson-Te Aho & Liu, 2010; Levy, 2002; Love, 2008; Macfarlane & Macfarlane, 2019; Masters-Awatere & Nikora, 2017; Nikora, 2007; Pitama et al., 2007; Smith, 1999; Valentine et al., 2017; Waitoki, 2018).

Te Tiriti breaches in psychology were famously highlighted in a 1985 survey exploring mātauranga Māori content in professional psychology courses throughout Aotearoa New Zealand (“A whiter shade of pale”; Abbott & Durie, 1987). At the time, no psychology staff members were Māori, and none of the programmes had Māori graduates in the previous two years. Further, few professional psychology courses incorporated taha Māori (a Māori dimension, or a bicultural perspective). Four decades later, Waitoki et al., (2023) published an update on professional psychology programme responsiveness to Māori. Analyses revealed improvements in the number of Māori teaching staff, Māori-focused content, and consultation with Māori advisory bodies, however, “concerns persist regarding the participation and graduation rates of tauira Māori in the programmes” (p. 11), and a lack of meaningful relationships between psychology programmes and Māori organisations or advisory bodies presented challenges for incorporating Māori content in psychology training. There is a notable lack of centrally recorded and reliable data about the overall professional psychology workforce (Levy, 2002, 2018) and, to our knowledge, no available data about the number of Māori health psychologists. Data from the clinical psychology workforce sheds some light on patterns within the broader psychology workforce, showing the total number of Māori clinical psychologists has remained stable at 6% since 2018 (Waitoki et al., 2024b).

In 2018, community psychologist Michelle Levy lodged WAI2575, a claim that the Crown had failed “to ensure psychology, as an academic discipline and profession, adequately meets the needs and demands of Māori” (Waitangi Tribunal, 2018, p. 1). Specifically, Levy argued that the Crown had breached Te Tiriti by failing to ensure psychologists are culturally competent to work with Māori, to increase the Māori psychology workforce, to support the development of an Indigenous Māori psychology profession, and to ensure that the New Zealand Psychologists Board and organisations delivering psychology training upheld their Tiriti obligations.

At the time of writing in 2024, the New Zealand Psychologists Board, the New Zealand Psychological Society, and the New Zealand College of Clinical Psychologists are in the process of preparing an apology to Māori for the harms done by the profession of psychology, as well as an action plan to address identified failings and deliberate harm (Waitoki et al., 2024a). He Paiaka Tōtora, a national rōpū (group) of Māori psychologists, are developing Te Tiriti educator capacity for the psychology profession, with an aspiration to enable Māori psychologies to live and promote Māori flourishing. Practitioners of critical health psychology are well-placed to involve themselves in such discipline and institution-level efforts to honour Te Tiriti o Waitangi. At the individual level, following the learning outlined in Textbox 1, we encourage practitioners of critical health psychology to consider and note down responses to the questions posed in Exercise 1. This is the first reflexive exercise presented in this chapter. We discuss reflexivity in more depth below.

Exercise 1. Reflexive questions and prompts for honouring Te Tiriti in critical health psychology practice

- what feelings come up for me when talking or reading about Te Tiriti o Waitangi?

- where might these come from?

- what are they telling me?

- what messages or stories have I previously heard or been taught about Te Tiriti?

- where have they come from?

- how does the learning in this chapter relate to previous learning about Te Tiriti?

- what am I already doing to honour Te Tiriti o Waitangi?

- what else could I be doing to uphold Te Tiriti o Waitangi in my personal life?

- what about in my professional practice?

- do my proposed actions map onto each article in the text?

- what gets in the way of me engaging with and honouring Te Tiriti o Waitangi?

- what supports could I seek, or plans could I make to address these barriers?

Reflexivity

Reflexivity has a “self-referential characteristic of ‘bending-back’ some thought upon the self” (Archer, 2009, p. 2). In critical health psychology, reflexivity is a process not just of reflection (where we might observe or think about our practice), but of questioning the cultural and temporal context in which our practice occurs. It is an ongoing process of self-awareness, where practitioners examine how their own values, assumptions, identities, and experiences shape their work. Whereas reflection is akin to looking in a mirror, we think reflexivity is better represented by surrealist artist René Magritte’s painting Not to Be Reproduced (La reproduction interdite), which depicts a man standing in front of a mirror, and his reflection showing him from behind. Reflexivity builds upon each moment of reflection, as new insights reshape how we see ourselves and our practice, creating a recursive and iterative process that deepens over time.

Reflexivity and critical health psychology practice

Reflexivity is more commonly discussed in research (particularly qualitative research) than in health psychology practice more broadly (see, for example, Jamieson et al., 2023; May & Perry, 2014; Palaganas et al., 2017; Watt, 2007). However, it is an essential tool for practitioners of health psychology aiming to challenge the “unproblematic adoption of a scientist-practitioner model” (Bolam & Chamberlain, 2003, p. 215). Bolam and Chamberlain (2003) argue that reflexive practice is what differentiates critical health psychology from its mainstream counterpart, and describe light and dark reflexivity as different dimensions of critical health psychology practice. Light reflexivity (akin to reflection) emphasises self-awareness and transparency without deeply challenging the status quo, power structures, or social norms. Light reflexivity focuses on procedural aspects of practice, such as asking, “What went well in the client session I just had, and what might I do differently next time?” or “Why did I experience that emotion when the client talked about…?” These questions promote self-awareness and enhance the practitioner’s responsiveness to clients but remain relatively contained within the immediate context of the therapeutic interaction. While light reflexivity is valuable, it does not necessarily require practitioners to confront broader social or political issues.

In contrast, dark reflexivity involves questioning the fundamental assumptions, social power dynamics, and ideologies underpinning practice. For instance, a practitioner might critically question the cultural roots or origins of a therapeutic approach and explore the ethical implications of using it with clients from diverse cultural backgrounds. Other examples include reflecting on how their own cultural identity or privilege shapes their interactions with clients, or examining how systemic inequalities, such as racism or classism, are perpetuated or challenged through their therapeutic interventions. Dark reflexivity requires practitioners to engage with discomfort and uncertainty, as they consider how their work intersects with broader systems of power, marginalisation, and inequality.

Reflexivity is closely tied to the concept of positionality, or where we are located in relation to our social and cultural identities (Savolainen et al., 2023). This might include our gender, ethnic or racial background, age, sexual orientation, class or socioeconomic status, geographical location, ability, religious or spiritual beliefs, and educational attainment. Positionality or reflexivity “statements” (which describe a practitioner’s identities) have become increasingly popular in research, however, scholars exploring reflexivity in research methodology warn against “laundry list” or “shopping list” reflexivity, where social and cultural identities are listed without exploration of their role in shaping the work (Folkes, 2023; Kohl & McCutcheon, 2015). Qualitative researchers also increasingly question binary notions of “insider” and “outsider” relationships in research and practice, as our identities are made up of multiple and intersecting facets (Dwyer & Buckle, 2009; Hayfield & Huxley, 2015). As such, we can typically find points of social and cultural commonality and difference with anyone we encounter in our practice. Practitioners of critical health psychology can usefully draw on concepts of “working the hyphen” (Fine, 1994, p. 70) and occupying “the space between” (Dwyer & Buckle, 2009, p. 54). By resisting binary discussion of whether shared identities are “better” or “worse” for our practice, we can instead consider how our experience of the world, our temporal and cultural context, and our interactions with others are shaped by (and, in turn, shape) these identities and subject positions.

Critical health psychology questions the (often implicit) directive to be a “blank slate” practitioner seen in other areas of psychology, where practitioners are expected to leave themselves at the door or attempt to practice in an “objective” fashion (Bolan & Chamberlain, 2003). While maintaining clear boundaries and protecting the therapeutic relationship are regarded as good practice across psychology, critical health psychology challenges where and how these boundaries are drawn, particularly when they intersect with culturally responsive approaches. In Aotearoa New Zealand, for example, self-disclosure is a key component of whakawhanaungatanga (building and maintaining relationships), essential for engaging with Māori clients in a culturally appropriate way. This practice can, however, conflict with traditional therapeutic views that caution against sharing too much of oneself, fearing it may blur the boundaries of the therapeutic relationship or compromise the safety of both practitioner and client. As we write this, Gloria is reminded of her own psychology training, where she was explicitly discouraged from sharing details about herself with clients that, in the Māori world, would be considered odd not to share.

Critical health psychology encourages practitioners to engage reflexively with the ethical and cultural dimensions of where those boundaries should be placed. This involves asking questions such as: “When I share of myself, who is this in service of? What is my rationale here?” In doing so, it promotes an understanding of boundaries that considers the power dynamics, cultural contexts, and relational needs that influence therapeutic practice. From a critical perspective, it is not only impossible to escape who we are; bringing ourselves into our work is often where we have our richest and most genuine interactions. Reflexivity enables practitioners to assess their practice and positionality through methods such as writing, journalling, peer discussions, or structured activities. See Exercise 2 for questions to help you engage reflexively with your positionality within relational spaces.

Exercise 2. Reflexive questions for practitioners of critical health psychology

- what social and cultural groups do I belong to? How salient are these group identities to me? How do I feel about being part of these groups?

- what does being healthy mean to me? Where did I learn this? Whose responsibility do I believe it is to promote health and prevent illness? What have my experiences of health and illness been like?

- what is the role of power within my life?

- what cultural frameworks do I draw upon to understand the world?

We then invite you to explore a conversation that you had during the past week. It may have been with a friend, whānau member, teacher, stranger, flat mate – anyone! Use some of the below questions as a guide to explore the conversation reflexively.

- what role might power have played in that interaction?

- what role did cultural systems and frameworks play during the interaction?

- how was I feeling during the interaction?

Challenges in reflexive practice

In our own teaching about professional practice, we observe a few common challenges for emerging practitioners of critical health psychology working to develop their reflexive practice. One challenge arises from the inclusion of the word “critical” in “critical health psychology” or “critical reflexivity”, which some students interpret as an invitation for “self-criticism”. This often leads them to focus on perceived mistakes, overlooking successes or the contextual and systemic factors at play. This tendency may also reflect a broader belief that demonstrating competence requires identifying problems, or a desire to pre-empt external critique by showing self-awareness about shortcomings. For instance, in classes on active listening and emotion validation, students often emphasise moments where they interrupted or rushed to problem-solve, rather than sitting with difficult feelings. While this kind of noticing is important, it can remain surface-level if not taken further. We encourage students to move beyond identifying problems to reflect on their emotional and embodied experiences during interactions. How does it feel to sit in silence during discomfort? What societal or cultural factors, such as the “happiness imperative” (Hyman, 2019), might drive the urge to resolve discomfort quickly? Reflexivity involves exploring these deeper layers and connecting personal insights to broader social, cultural, and systemic contexts.

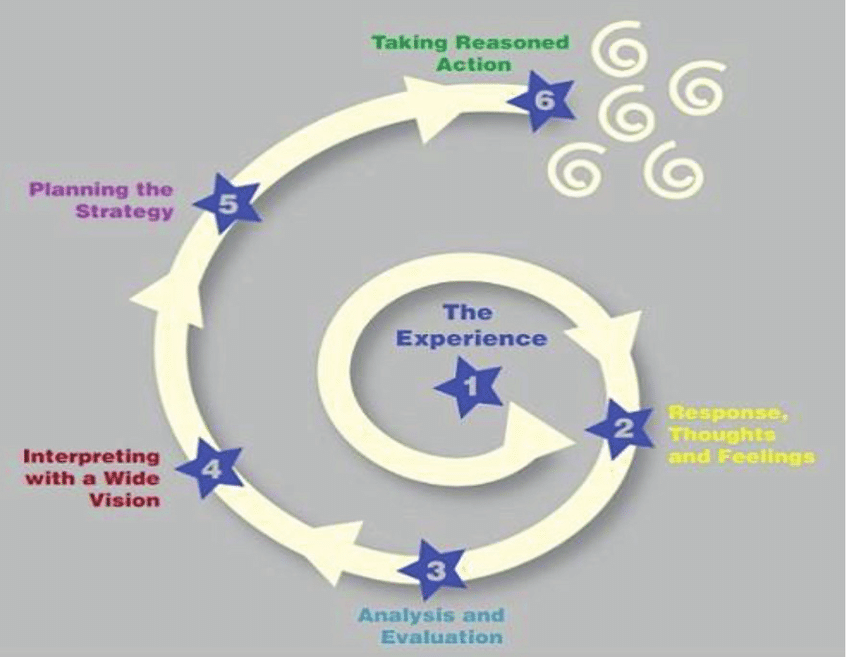

The second challenge we observe in developing reflexive practice is differentiating reflexivity from rumination. Although rumination and reflexivity have some commonalities (they both entail considered thought on an experience or issue), rumination tends to be cyclical in nature and negative in focus (Lengelle et al., 2016). As such, rumination rarely results in action or problem solving. When ruminating, we tend fall “into a bottomless pit of reflection upon reflection” (Lengelle et al., 2016, p. 101). Reflexivity, in contrast, should always end in taking action. Wear et al. (2012) note that action can involve “taking a risk, redressing a wrong, or, at the very least, resolving to do things differently the next time” (p. 605).

We use Mitchell’s (2017) Six Step Spiral for Critical Reflexivity (see Figure 3.1.2) as a visual depiction of the process of moving from an experience, to analysing our response to the experience, to taking reasoned action grounded in our analysis. Mitchell’s (2017) spiral ends with several smaller spirals, signalling the ongoing and iterative nature of critical reflexivity. Rather than being “one and done”, we move through the critical reflexivity spiral continuously over the course of our health psychology practice. As practitioners located in Aotearoa New Zealand, we see our own tohu of a koru in the spiral, which conveys growth and the idea of perpetual movement. We are reminded of the whakataukī “Ka mua, ka muri” (walking backwards into the future), which emphasises the importance of looking to the past to inform the future. In our next section on ethics, we introduce ethical frameworks that practitioners of critical health psychology can draw on to inform their reflexive practice.

Ethical decision making

Ethics are a system of moral principles, and a philosophical discipline concerned with moral right and wrong. Professional ethics offer a set of guidelines or principles for use in a workplace or professional setting. Practitioners of psychology in Aotearoa are guided by the Code of Ethics for Psychologists Working in Aotearoa/New Zealand (the Code of Ethics); a document jointly prepared by the New Zealand Psychological Society, the New Zealand College of Clinical Psychologists, and the New Zealand Psychologists Board (Code of Ethics Review Group, 2002).

The Code of Ethics for Psychologists Working in Aotearoa New Zealand

The Code of Ethics applies to all members of both the New Zealand Psychological Society (NZPsS) and the New Zealand College of Clinical Psychologists (NZCCP), as well as all other psychologists registered with the New Zealand Psychologists Board. As such, the Code of Ethics applies not only to registered psychologists, but to NZPsS and NZCCP members involved in “research, teaching, supervision of trainees, development and use of assessment instruments, organisational consulting, social intervention, administration, and other workplace activities” (p. 2). The Code of Ethics is intended to:

- unify the practices of the profession of psychology.

- guide psychologists in ethical decision-making.

- present a set of guidelines that inform the public of the professional ethics of the profession of psychology.

We think of the Code of Ethics as a roadmap to guide practitioners of psychology. The current version, published in 2002, is the second iteration of the Code of Ethics in New Zealand (the first was published in 1986), and the first to directly reference Te Tiriti o Waitangi (Fitzgerald, 2021). It is based in the same four principles found in the Universal Declaration of Ethical Principles for Psychologists (International Union of Psychological Science, 2008) and helps us to articulate and reflect on our options for ethical decision making. The Code sits alongside other important guiding documents for the profession, including the Core Competencies for Psychologists (New Zealand Psychologists Board, 2018), a range of best practice guidelines developed or endorsed by the New Zealand Psychologists Board (e.g., Working with sex, sexuality and gender diverse clients; Informed consent; Supervision), and relevant legislation (e.g., Health Practitioners Competence Assurance Act 2003). Textbox 2 summarises the psychologists Code of Ethics.

Textbox 2. Code of Ethics for Psychologists Working in Aotearoa/New Zealand

The Code of Ethics identifies four key ethical principles. Under each principle are several values that are in turn linked to practice implications. The Code also presents a six-step process for ethical decision making, which highlights the importance of identifying relevant ethical issues, developing potential courses of action (preferably in consultation with a colleague or supervisor), and analysing the likely risks and benefits of each course of action using the Code’s principles, values, and practice implications.

Principle 1: Respect for the dignity of persons and peoples

Principle 1 emphasises the need for psychologists to show respect and grant dignity to all people, based on their common humanity. This includes recognition of, and sensitivity to, cultural and social diversity. Principle 1 refers to the Treaty of Waitangi as the basis of respect between Māori and non-Māori in Aotearoa New Zealand. It includes specific guidance about:

- obtaining training and advice to support culturally safe practice.

- promoting peoples’ right to privacy and protecting confidentiality.

- obtaining informed consent.

Principle 2: Responsible caring

Principle 2 outlines the promotion of wellbeing as a basic ethical expectation of the discipline of psychology. As such, psychologists should engage in activities that will benefit members of society. It includes specific guidance for psychologists about:

- using respectful and effective procedures, instruments, and interventions.

- attaining and maintaining adequate levels of knowledge and skills to practise.

- practising within their area of expertise, with regular supervision and evaluation.

- providing responsible care to those who may be disadvantaged or oppressed.

- recognising the vulnerable status of children.

- conducting research that meets current ethical standards.

Principle 3: Integrity in relationships

Principle 3 notes that psychologists must seek to do right in their relationships with others, and that integrity in relationships is vital to maintain public confidence in the discipline. It includes specific guidance for psychologists about:

- accurately representing their qualifications, experience, and competence.

- ensuring accurate, complete, and clear communication.

- ensuring their personal values and beliefs do not disadvantage those they work with.

- maintaining appropriate boundaries in their professional relationships.

- avoiding dual relationships where possible and acting to address conflicts of interest.

Principle 4: Social justice and responsibility to society

Principle 4 states that psychologists have a responsibility to promote the wellbeing of communities and society. This includes acknowledging their position of power and influence, and challenging unjust social structures. It includes specific guidance for psychologists about:

- keeping informed about the needs, current issues, and problems of society.

- speaking out when they possess knowledge that bears on important societal issues.

- ensuring psychological knowledge will be used for beneficial purposes.

- bringing incompetent or unethical behaviour of colleagues to appropriate bodies.

The Code is currently undergoing a third revision, in recognition of the changing landscape in psychology practice over the last 22 years, and the need to “ensure it more strongly reflects the profession of Psychology’s commitment to honouring Te Tiriti o Waitangi” (Stewart, 2024, p. 1). The revised Code will sit alongside a new Code of Conduct. Whereas the Code of Ethics guides psychologists’ practice, the Code of Conduct will outline behaviours that are mandated as part of their professional work. In 2021 a Code of Ethics Review Group was established, made up of members from He Paiaka Tōtara (a rōpū of Māori psychologists), Pasifikology (a rōpū of Pasifika psychologists), the New Zealand College of Clinical Psychologists, the New Zealand Psychological Society, and the New Zealand Psychologists Board. All psychologists were surveyed in 2022 for their opinions about the strengths and weaknesses of the Code, and in 2023 feedback from key stakeholders across the discipline was sought and incorporated. As well as reorienting the Code to better reflect mātauranga Māori, the Psychologists Board has indicated that the revised Code will articulate the ethical considerations for the use of new technologies (e.g., artificial intelligence), provide guidance on managing (rather than avoiding) dual relationships (given the small and interconnected nature of many communities in Aotearoa), and explicitly recognise the need for psychologists to practice their own self-care, advocate for their clients, and aim to use empowering strengths-based approaches (Stewart, 2024).

Using the Code to guide ethical decision making

Some ethical decisions in the practice of critical health psychology are relatively straightforward—as a cut-and-dried example, it is widely agreed that practitioners of psychology should not enter sexual or romantic relationships with those they hold power over, such as their clients and students (see Code of Ethics 2.1.10). Often, however, there is no singular “ethical” decision to be made in a particular critical health psychology practice setting; ethical decision-making is context dependent and requires practitioners to weigh up the likely costs and benefits of different paths forward. In our teaching, we use ethical scenarios as prompts for students to develop their ethical reasoning. Sometimes these come in the form of ethical continua, where we will ask students to physically place themselves in the classroom depending on where they fall on a particular issue. Ethical continuum exercises also provide opportunities to explore how our decisions might change in light of specific contextual factors. See Exercise 3 for a list of ethical scenarios to work through, using the Code of Ethics to guide your decision making.

Exercise 3. Ethical scenarios with prompting questions

Take some time to work through the following ethical scenarios. For each one, note down:

- your initial response about the best path forward. If you answer “it depends”: what further information would you need to make your decision?

- a justification for your initial response with reference to Code of Ethics principles.

- whether you would change your response in light of your analysis of the Code.

- whether you would change your response given the specific contextual factors below.

1. You are a psychologist in a community-based health setting and have been working with Eileen for six months. You are coming to the end of your therapeutic relationship and Eileen wishes to give you a thank-you gift for the time you have spent together. She presents you with a gold watch! Is this gift okay to accept?

Specific contextual factors: (1) How does the monetary value of the gift impact upon your approach? What if the gift were a hand-woven flax basket, instead of a gold watch? What if it was a box of chocolates? (2) Do your views on accepting the gift shift depending on Eileen’s socioeconomic situation? For example, would your perspective change if Eileen were a multi-millionaire? What if Eileen were earning the living wage?

2. It’s 3:00 PM and time for your first meeting with a new whai ora. The door opens, and to your surprise…. your hairdresser Paora walks in! Is having a therapeutic relationship with Paora appropriate?

Specific contextual factors: (1) How might the setting you live impact on your consideration of dual relationships? For example, what would your approach be if you were living in a city with a population of 1 million, versus a rural town with one hairdresser and one psychologist? (2) Do your views on seeing Paora change depending on your work setting? What if you worked in a service with only one publicly funded psychologist, meaning Paora’s only option is to see you?

3. You are a Lecturer in critical health psychology and log on to Instagram at the end of the day for some much-needed mindless scrolling to find your Master’s thesis supervisee Daisy has requested to follow you. You and Daisy have several mutual friends and are only a few years apart in age. Do you accept the follow request?

Specific contextual factors: (1) What if the order of events was the other way around: you knew Daisy socially and followed each other on social media, and she then approached you to enquire about Master’s thesis supervision. Would you agree to supervise Daisy? (2) How might the nature of your social media presence impact your decision? For example, what would your approach be if you posted interesting critical health psychology research on your Instagram page, versus photos of you and your friends attending music festivals?

Cultural safety

Culture (the way of life of a particular group of people at a particular time; Cambridge Dictionary, 2024) is central to critical health psychology, as health and wellbeing are inextricably shaped by cultural context. Culture informs health determinants, constructions of meaning, and decision making for practitioners and clients alike, and cultural difference maps on to power and inequality (Hygens & Nairn, 2016). The New Zealand Psychologists’ Board Core Competencies (2018) note that culture “includes, but is not restricted to, age or generation, iwi, hapū and tribal links; gender; sexual orientation; occupation and socioeconomic status; cultural and epistemological frame of reference; ethnic origin or migrant experience; religious or spiritual belief; and disability” (p. 6). Culture is closely connected to the concept of positionality, discussed above.

Practitioners of critical health psychology (as well as psychology and health more generally) use a range of terms to conceptualise engagement with culture. The Code of Ethics for practitioners of psychology and Core Competencies for psychologists include references to cultural safety, cultural competence, sensitivity to cultural diversity, cultural knowledge, and cultural appropriateness (Code of Ethics Review Group, 2002; New Zealand Psychologists Board, 2018). We have also encountered the terms cultural humility (Danso, 2018; see also Chapter 1.1), cultural proficiency (Kosoko-Lasaki et al., 2008), and transcultural competence (Torry, 2005). A so-called “smorgasbord of definitions and conceptualizations” (Danso, 2018, p. 410) has generated significant controversy around culture-related constructs, often with calls to reject one framing in favour of another. We discuss two frameworks (cultural competency and cultural safety) that aim to address health inequities below. Here, we specifically focus on engagement with te ao Māori, given our unique positioning in Aotearoa New Zealand, though we emphasise that Māori are just one of many minoritised cultural groups in healthcare settings. For comprehensive discussion of psychology practice with other cultural groups (including Pasifika and Asian people; migrants and refugees; and Rainbow people), see Waitoki et al. (2016).

Cultural competency (or cultural competence) is perhaps the most widely used framework for cultural engagement in health practice. Originating in the late 1980s and early 1990s, cultural competence typically focuses on acquiring the awareness, knowledge, and skills to work effectively with individuals from diverse cultural backgrounds (see Sue et al., 1982). Cultural competency has been critiqued for conceptualising competence as a static state or skill, rather than an ongoing process, and for a failure to acknowledge the culture of the practitioner or environment, assuming a culturally neutral practitioner, and the recipients of care as cultural ‘others’ (Curtis et al., 2019; Kumagai & Lypson, 2009).

Cultural safety has emerged as an alternative framework from which to engage with culture in healthcare practice. Developed by Māori nurse educator Irihapeti Ramsden, cultural safety goes beyond cultural competency by focusing on power dynamics, systemic inequalities, and the impact of colonisation on health outcomes (Papps & Ramsden, 1996; Ramsden, 2002). It requires practitioners to develop a critical consciousness (see Friere, 1970)—an ability to reflect on their own cultural biases, privilege, and assumptions to create a safe and respectful environment for individuals from diverse cultural backgrounds (Curtis et al., 2019). Most importantly, whether a health practitioner is culturally safe is determined by those receiving care rather than those providing it (Gerlach, 2012; Papps & Ramsden, 1996; Ramsden, 2002). Curtis et al. (2019) argue that a shift from cultural competence to safety is essential to achieve health equity for Māori in Aotearoa New Zealand, and that health practitioners, organisations, and systems “must be prepared to critique the ‘taken for granted’ power structures and be prepared to challenge their own culture and cultural systems rather than prioritise becoming ‘competent’ in the cultures of others” (p. 1).

Cultural appropriation and appreciation

Calls for a culturally safe critical health psychology practice that honours Te Tiriti o Waitangi prompts questions and discussion about Pākehā and tauiwi engagement in Māori cultural practices. Elana Curtis, a public health physician and academic known for her work on cultural safety, has been clear that widespread investment in practices such as pōwhiri, mihi whakatau, and karakia in healthcare settings has not eliminated Māori health inequities, and warns of the “karakia sandwich”, where healthcare practitioners learn to say a karakia at the beginning and end of a hui, while the middle of the sandwich “stays racist, stays uncritical, stays actually dangerous for Māori” (Te Whatu Ora, 2024, para. 14).

The “karakia sandwich” that Curtis describes is not benign but causes active harm for Māori. First, when health systems, institutions, and practitioners appear to be working towards Māori health equity through visible cultural practices, this can shift attention from the structural (and often invisible) factors that perpetuate inequity, maintaining the status quo. An example of this is a healthcare service with a Māori name that decorates their space with Māori art but fails to address structural barriers to accessing their service (e.g., inaccessible clinical locations or systemic racism in health screening and referral). A second danger is the potential for Indigenous knowledges to be co-opted or appropriated if Māori practices are approached as a tick box rather than with genuine engagement. Waitoki (2012, p. 60) notes:

For Māori, when language, culture and knowledge of the colonised are used in an un-reflexive way it serves to affirm the group of people who already occupy the position of power (Bertanees & Thornley, 2004). While there is a need for bicultural initiatives and cultural competency training in psychology, what is not needed is a wholesale misuse and lack of understanding of Māori culture and its relevance to psychology.

Indeed, Māori cultural practices are inherently spiritual practices: karakia, waiata, and pōwhiri are imbued with tapu (which can be translated as ‘under atua protection’), meaning they relate to an unseen or intangible realm, as well as the physical world in which we live (see Ngawati et al., 2018). When Māori practices are co-opted in a way that loses connection with their true purpose, this tapu is diluted or diminished and has significant negative implications for Māori wellbeing. Moreover, the giving of Māori culture to non-Māori is not neutral. Māori culture and language have been forcefully taken and violently suppressed through the process of settler colonisation (Moewaka Barnes & McCreanor, 2019). For many Māori, seeing Crown institutions breaching Te Tiriti while using the same language their grandparents were harshly punished for speaking is akin to rubbing salt in a very fresh wound.

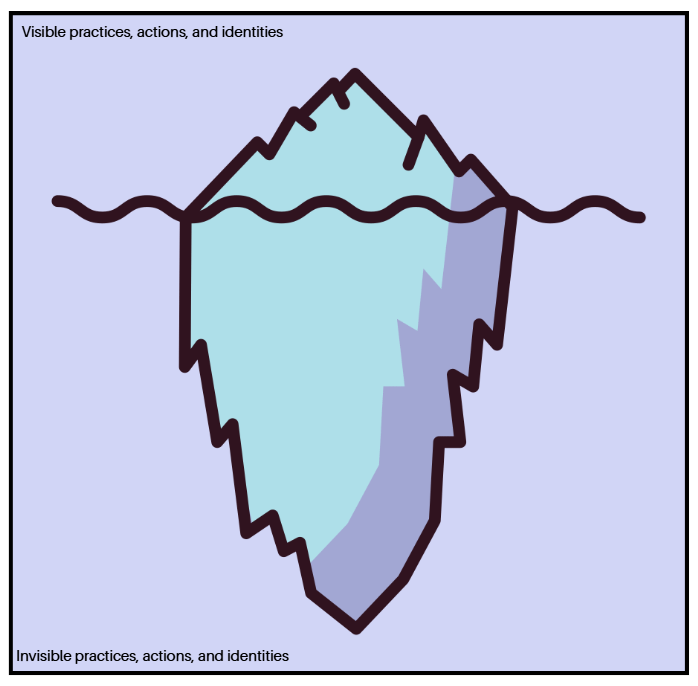

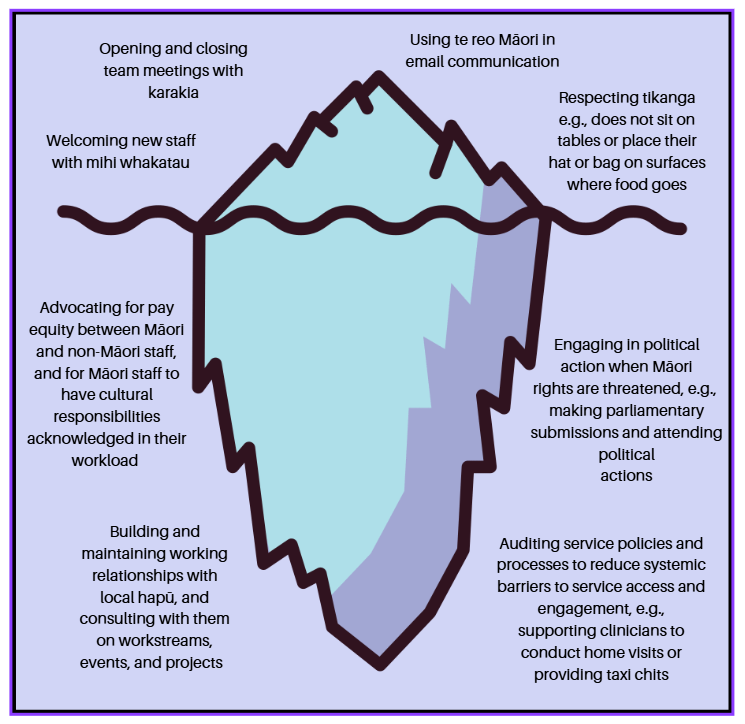

Concerns about health practitioners’ cultural appropriation or misuse and misunderstanding of tikanga, te reo, and mātauranga Māori can lead to another problem entirely: Pākehā paralysis. Pākehā paralysis refers to a state of inaction or reluctance among non-Māori to engage with the Māori world, often stemming from discomfort, guilt, or a fear of getting things wrong (Citizen, 2020; Hotere-Barnes, 2015; Tolich, 2002). This phenomenon also results in a failure to address systemic health inequities and can mean that Māori do not see their culture reflected in healthcare spaces. Health systems in Aotearoa predominantly reflect Eurocentric knowledge frameworks and ways of doing and being, resulting in a structure that is culturally familiar and accessible primarily to Pākehā (Came-Friar et al., 2019; Waitoki et al., 2024a). The cultural safety iceberg is a tool to help you reflect upon practices or components that are visible to some people (the top of the iceberg) and less visible or invisible to other people (beneath the surface of the water) shown in Textbox 3.

Textbox 3. The cultural safety iceberg

The cultural safety iceberg is a tool to help you reflect upon your practices. Visible components are important, as Māori need to see themselves and their culture respectfully represented in health psychology spaces. However, these should never be seen as sufficient. The less visible or invisible practices that disrupt inequitable power structures are essential for a culturally safe health psychology. Below is an example of how a health psychology team leader might enact cultural safety within their health service.

An iceberg model can also be used to reflect upon your own identity and positionality. The surface area contains your qualities and attributes that are obvious and easily identifiable by others. As the iceberg goes deeper, identify the less visible or invisible aspects of yourself that influence how you understand, experience, and navigate the world. These aspects may involve invisible cultural identities, political beliefs, sense of time, relationships and responsibilities to others, and core values. You may then consider how these core aspects interface with your cultural identities. This exercise encourages you to consider the layers of your identity and positionality that you may not have explicitly explored before. It also serves as an ever-timely reminder that all of us—from our colleagues to tangata whai ora to those we pass by on the street—carry hidden depths below the surface that we may or may not ever see.

You will find a blank cultural safety iceberg at the end of the chapter. You can use this to consider visible and invisible practices to create cultural safety with a particular cultural group, or to further explore your own cultural identities and subject positions.

Cultural appropriation or co-option of Indigenous knowledges on one hand, and Pākehā paralysis on the other, have at times left our own critical health psychology students befuddled, or feeling stuck between a cultural rock and a hard place: how can practitioners of critical health psychology contribute to the decolonisation of critical health psychology, revitalisation of te reo Māori, and emphasise the inherent value and validity of mātauranga and tikanga Māori, all in the spirit of appreciation rather than appropriation? If I am not going to do it right, they ask, am I better off not attempting to engage at all, to make sure I do not offend anyone? In response, we encourage our students to approach cultural safety in concert with the frameworks previously introduced in this chapter (in particular, reflexivity and Te Tiriti o Waitangi). If you are wondering whether or how to engage in te ao Māori, we recommend starting with the exercises outlined in the chapter so far. We illustrate this approach in Textbox 3 with the “cultural safety iceberg”, a metaphor for the visible and less visible aspects of cultural engagement. Starting with the actions under the surface of the water (including learning more about settler colonialism and how this process is enacted in Aotearoa New Zealand, as well as the history of the land on which you live, and your own whakapapa and positioning in relation to Te Tiriti) provides a foundation to engage more confidently in actions above the surface. We also encourage you to consider the purpose of different cultural practices, and how their purpose might be realised in a way that is respectful and authentic (or in Māori terms, tika and pono). Textbox 4 provides an example with an exploration of the purpose of karakia, along with guiding questions to consider when engaging in karakia in your practice.

Textbox 4. Use of karakia in critical health psychology practice

Karakia are a set form of words (sometimes referred to as a blessing, incantation, or prayer) used to invoke spiritual guidance and protection, or to state or make effective a ritual activity. Karakia can be a set form of words, however, proficient speakers of te reo will compose karakia as they speak. They help Māori to navigate tapu and to acknowledge the mana inherent in all things. Karakia can be formal or informal. They can be used to bless food, before a journey to protect against harm, to start or end the day, to express gratitude, or to ensure a task or activity is successful or runs smoothly.

When used to open and close a hui or gathering, karakia can:

- help us transition from one focus to another.

- bring those present together for a common purpose.

- set an intention for the kaupapa at hand.

- help to centre and ground those gathered.

Reciting Māori karakia is just one way to achieve the purposes outlined above. As practitioners of critical health psychology, we have many ways to bring people together and transition between spaces. Alex often plays music before teaching a class to set the tone and settle students into the teaching room, and he uses this time to connect with students one-to-one with a fun or thought-provoking question or thought experiment. Gloria has opened sessions in her clinical practice by easing into conversation while making a hot drink and often closes sessions with tamariki using a te reo Māori board game to help transition to a lighter space before she sends them on their way. These practices may not connect us to atua Māori in the same way as a karakia, but are selected intentionally to recognise that invocation of spiritual guidance is not appropriate in every setting or context. At other times (e.g., when presenting workshops about te Tiriti o Waitangi, or when mutually decided with whai ora), Gloria does begin and end classes and clinical sessions with karakia. Keep in mind that karakia is extremely important for many (but not all) Māori, and that many non-Māori find karakia helpful and settling too.

If you are planning to use a Māori karakia, check in using the following questions:

- what is the purpose of using a karakia in this context?

- have you chosen a karakia that aligns with your purpose?

- have you explored how this karakia is pronounced?

- do you have a sense of what this karakia means to you?

- what do you know about the origins of this karakia?

- what less visible or invisible actions are you engaging in between opening and closing karakia (in Curtis’ terms: in the filling of your sandwich), or outside of the hui, to make your context and practice culturally safe?

If you are unsure of any of the answers to the above questions, this is a prompt to extend your learning about te reo Māori and karakia, or to set aside time for reflexive exploration and action planning around culturally safe practice (for further discussion about use of karakia in practice, see NiaNia et al., 2016; NiaNia et al., 2025).

Conclusion

Critical health psychology practice is about making the world a better place by questioning taken-for-granted knowledge systems and challenging existing unequal power structures. In this chapter, we have taken you on a whirlwind tour of key frameworks to support the (at times, weighty!) aspiration to create a social justice-oriented health psychology practice in Aotearoa, New Zealand. Discussing Te Tiriti o Waitangi, reflexivity, ethics, and cultural safety is a tall order for one book chapter; each of these topics and frameworks are explored with far more nuance and detail elsewhere, and we encourage you to use our reference and Te Tiriti reading lists to guide your further reading. We do, however, hope that we have provided an adequate introduction to these frameworks, and the relationships between them, to start you on your way. Make change in your spheres of influence, be kind to yourself, and keep fighting for social justice and health equity. Toitū te Tiriti!

Blank Cultural safety iceberg

Further reading

Te Tiriti o Waitangi: Easily digestible

Hori & Dewes, T. K. M. (Hosts). (2024, November 12). Te Tiriti Party (Parts 1 & 2) [Visual Podcast episode]. In Hori on a Hīkoi – Ngā Porokāte. RNZ. https://www.rnz.co.nz/programmes/hori-on-a-hikoi/story/2018963791/hori-on-a-hikoi-nga-porokate-episode-4-te-tiriti-party-parts-1-and-2-veronica-tawhai

Jackson, M. (2019). He Tohu: Interview with Moana Jackson. National Library.

https://natlib.govt.nz/he-tohu/korero/interview-with-moana-jackson

Morris, T., Calman, R., Derby, M., & Walker, P. (2019). Te Tiriti o Waitangi / The Treaty of Waitangi. Lift Education.

Ngata, T. (2020). What’s required from Tangata Tiriti. Tina Ngata. https://tinangata.com/2020/12/20/whats-required-from-tangata-tiriti/

Rātana, L., & van Eeden, L. (2020). Understanding Te Tiriti o Waitangi. Re: News. https://www.renews.co.nz/explainer-understanding-te-tiriti-o-waitangi/

Smail, R. (2024). Understanding Te Tiriti: Handbook about Te Tiriti o Waitangi. Wai Ako Books.

Snowden, T. P. & Gloyne, P. (2023, February 3). Waitangi 2023 [Audio Podcast episode]. In Taringa. Te Wānanga o Aotearoa. https://www.taringapodcast.com/e/taringa-ep-273-special-feature-waitangi-2023/

Te Tiriti o Waitangi, colonisation, and decolonisation: Bigger reads

Elkington, B., Jackson, M., Kiddle, R., Mercier, O. R., Ross, M., Smeaton, J., & Thomas, A. (2020). Imagining decolonisation. Bridget Williams Books

Huygens, I., Murphy, T., & Healy, S. (2012). Ngapuhi speaks: The independent report on the Ngapuhi nui tonu claim. Te Kawariki & Network Waitangi Whangarei (Inc).

Mikaere, A. (2011). Colonising myths: Māori realities. Huia Publishers.

Mulholland, M., & Tawhai, V. M. H. (2010). Weeping waters: The Treaty of Waitangi and constitutional change. Huia Publishers.

Mutu, M. (2013, April 22). Te Tiriti o Waitangi in a future constitution: Removing the shackles of colonisation [Paper presentation]. Robson Lecture, Napier, New Zealand. http://www.converge.org.nz/pma/shackles-of-colonisation.pdf [PDF]

Ngata, T. (2019). Kia mau: Resisting colonial fictions. Kia Mau Campaign.

The Working Group on Constitutional Transformation. (2016). He whakaaro here whakaumu mō Aotearoa: The report of Matike Mai Aotearoa. https://nwo.org.nz/resources/report-of-matike-mai-aotearoa-the-independent-working-group-on-constitutional-transformation/

Waitangi Tribunal reports, a valuable source of Tiriti evidence, can be found online at http://www.waitangi-tribunal.govt.nz/reports

Walker, R. (2004). Ka whawhai tonu matou: Struggle without end. Penguin.

References

Abbott, M. W., & Durie, M. H. (1987). A whiter shade of pale: Taha Māori and professional psychology training. New Zealand Journal of Psychology, 16(2), 58–71. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/1989-06579-001

Archer, M. S. (2009). Conversations about reflexivity. Routledge.

Bennett, S. T., Flett, R. A., & Babbage, D. R. (2014). Culturally adapted cognitive behaviour therapy for Māori with major depression. The Cognitive Behaviour Therapist, 7, e20. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1754470X14000233

Bolam, B., & Chamberlain, K. (2003). Professionalization and reflexivity in critical health psychology practice. Journal of Health Psychology, 8(2), 215-218. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105303008002661

Brown, H., & Bryder, L. (2023). Universal healthcare for all? Māori health inequalities in Aotearoa New Zealand, 1975–2000. Social Science & Medicine, 319, 115315. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.115315

Burns, C., Hetaraka, M., & Jones, A. (2024). Te Tiriti o Waitangi: The Treaty of Waitangi, principles and other representations. New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies, 59, 15–29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40841-024-00312-y

Cambridge Dictionary. (2024). Culture. In Cambridge Dictionary. Retrieved February 14, 2024, from https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/culture

Came, H., & McCreanor, T. (2015). Pathways to transform institutional (and everyday) racism in New Zealand. Sites: New Services, 12(5), 1–25.

Came-Friar, H., McCreanor, T., Manson, L., & Nuku, K. (2019). Upholding Te Tiriti, ending institutional racism and Crown inaction on health equity. New Zealand Medical Journal, 132(1492), 61–66. https://nzmj.org.nz/journal/vol-132-no-1492/upholding-te-tiriti-ending-institutional-racism-and-crown-inaction-on-health-equity

Chamberlain, K., & Murray, M. (2009). Critical health psychology. In D. Fox, I. Prilleltensky, & S. Austin (Eds.), Critical psychology: An introduction (2nd ed., pp. 144–158). Sage Publications.

Chamberlain, K., Lyons, A. C., & Stephens, C. (2018). Critical health psychology in New Zealand: Developments, directions and reflections. Journal of Health Psychology, 23(3), 457–471. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105317734871

Cherrington, L. (2003). The use of Māori mythology in clinical settings: Training issues and needs. In L. W., Nikora, M. Levy, B. Masters, W. Waitoki, N. Te Awekotuku, & R. J. M. Etheredge (Eds.), The proceedings of the National Māori Graduates of Psychology Symposium 2002: Making a difference (pp.117–120). Māori and Psychology Research Unit, University of Waikato. https://researchcommons.waikato.ac.nz/entities/publication/298a4d69-0922-4275-8417-7f1a78d76f26

Citizen, J. (2020). Inaction is also action: Attempting to address Pākehā paralysis. Scope: Contemporary Research Topics (Learning & Teaching), 9, 81-84. https://researcharchive.wintec.ac.nz/id/eprint/7639/

Code of Ethics Review Group. (2002). Code of ethics for psychologists working in Aotearoa/New Zealand. New Zealand Psychological Society, New Zealand Psychologists Board, New Zealand College of Clinical Psychologists. https://www.nzccp.co.nz/assets/Uploads/Code-of-Ethics-English.pdf [PDF]

Curtis, E., Jones, R., Tipene-Leach, D., Walker, C., Loring, B., Paine, S. J., & Reid, P. (2019). Why cultural safety rather than cultural competency is required to achieve health equity: A literature review and recommended definition. International Journal for Equity in Health, 18, 174. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12939-019-1082-3

Danso, R. (2018). Cultural competence and cultural humility: A critical reflection on key cultural diversity concepts. Journal of Social Work, 18(4), 410–430. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468017316654341

Durie, M. (1994). Whaiaora – Māori health development. Oxford University Press.

Dwyer, S. C., & Buckle, J. L. (2009). The space between: On being an insider-outsider in qualitative research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 8(1), 54–63. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690900800105

Fine, M. (1994). Working the hyphens: Reinventing self and other in qualitative research. In N. Denzin & Y. Lincoln (Eds.), Handbook of qualitative research (pp. 70–82). Sage.

Fitzgerald, J. (2021). The code of ethics for psychologists working in Aotearoa New Zealand. In K. L. Parsonson (Ed.), Handbook of international psychology ethics: Codes and commentary from around the world (pp. 94–104). Taylor & Francis.

Folkes, L. (2023). Moving beyond ‘shopping list’ positionality: Using kitchen table reflexivity and in/visible tools to develop reflexive qualitative research. Qualitative Research, 23(5), 1301-–318. https://doi.org/10.1177/14687941221098922

Friere, P. (1970). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Herder and Herder.

Gerlach, A. J. (2012). A critical reflection on the concept of cultural safety. Canadian Journal of Occupational Therapy, 79(3), 151–158. https://doi.org/10.2182/cjot.2012.79.3.4

Hayfield, N., & Huxley, C. (2015). Insider and outsider perspectives: Reflections on researcher identities in research with lesbian and bisexual women. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 12(2), 91–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/14780887.2014.918224

Health Practitioners Competence Assurance Act 2003. https://www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/2003/0048/latest/DLM203312.html

Hotere-Barnes, A. (2015). Generating ‘Non-stupid optimism’: Addressing Pākehā paralysis in Māori educational research. New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies, 50(1), 39–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40841-015-0007-y

Huygens, I. & Nairn, R. (2016). Ethics and culture: Foundations of practice. In W. W. Waitoki, J. S. Feather, N. R. Robertson, & J. Rucklidge (Eds.), Professional practice of psychology in Aotearoa New Zealand (3rd ed., pp. 15–26). New Zealand Psychological Society.

Hyman, L. (2019). Happiness: A societal ‘imperative’? In N. Hill, S. Brinkmann, & A. Petersen (Eds.), Critical happiness studies (pp. 98–109). Routledge.

Jackson, M. (2019). He Tohu: Interview with Moana Jackson. National Library. https://natlib.govt.nz/he-tohu/korero/interview-with-moana-jackson

Jamieson, M. K., Govaart, G. H., & Pownall, M. (2023). Reflexivity in quantitative research: A rationale and beginner’s guide. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 17(4), e12735. https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12735

Kennedy, B. J., Tassell-Matamua, N. A., & Stiles-Smith, B. (2021). Psychology in Aotearoa New Zealand. In G. J. Rich & N. A. Ramkumar (Eds.), Psychology in Oceania and the Caribbean (pp. 115–132). Springer.

Kohl, E., & McCutcheon, P. (2015). Kitchen table reflexivity: Negotiating positionality through everyday talk. Gender, Place & Culture, 22(6), 747-763. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2014.958063

Kosoko-Lasaki, S., Cook, C. T., & O’Brien, R. L. (2008). Cultural proficiency in addressing health disparities. Jones & Bartlett Publishers.

Kumagai, A. K., & Lypson, M. L. (2009). Beyond cultural competence: Critical consciousness, social justice, and multicultural education. Academic Medicine, 84(6), 782–787. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181a42398

Lawson-Te Aho, K., & Liu, J. H. (2010). Indigenous suicide and colonization: The legacy of violence and the necessity of self-determination. International Journal of Conflict and Violence, 4(1), 124–133. https://doi.org/10.4119/ijcv-2819

Lengelle, R., Luken, T., & Meijers, F. (2016). Is self-reflection dangerous? Preventing rumination in career learning. Australian Journal of Career Development, 25(3), 99–109. https://doi.org/10.1177/1038416216670675

Levy, M. (2002). Barriers and incentives to Māori participation in the profession of psychology: A report for the New Zealand Psychologists Board. Māori and Psychology Research Unit. https://researchcommons.waikato.ac.nz/handle/10289/457

Levy, M. (2018). Indigenous psychology in Aotearoa: Reaching our highest peaks. New Zealand Psychological Society & New Zealand College of Clinical Psychologists. https://www.psychology.org.nz/journal-archive/Reaching-Our-Highest-Peaks-2018.pdf [PDF]

Love, C. (2008). An indigenous reality check. New Zealand Journal of Psychology, 37(3), 26-33. https://www.psychology.org.nz/journal-archive/NZJP-Vol373-2008-5-Love.pdf [PDF]

Ludbrook, J. (2015). The principles of the Treaty of Waitangi: Their nature, their limits and their future (No. 117/2015). Victoria University of Wellington Legal Research Paper Series. https://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2539314

Macfarlane, A., & Macfarlane, S. (2019). Listen to culture: Māori scholars’ plea to researchers. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand, 49(Suppl. 1), 48–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/03036758.2019.1661855

Masters-Awatere, B., & Nikora, L. W. (2017). Indigenous programmes and evaluation: An excluded worldview. Evaluation Matters—He Take Tō Te Aromatawai, 3, 40–66. https://www.nzcer.org.nz/system/files/journals/EM2017_3_40.pdf [PDF]

Matarazzo, J. D. (1980). Behavioral health and behavioral medicine: Frontiers for a new health psychology. American Psychologist, 35(9), 807–817.

May, T., & Perry, B. (2014). Reflexivity and the practice of qualitative research. In U. Flick (Ed.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative data analysis (pp. 109–122). Sage Publishing.

McCreanor, T., Came, H., & Berghan, G. (2024). Propagating the myth that Māori ceded sovereignty. In M. S Turei, N. R. Wheen, & J. Hayward (Eds.), Te Tiriti o Waitangi relationships: People, politics and law (pp. 11–23). Bridget William Books.

Ministry of Health. (2024). Te Tiriti o Waitangi framework. https://www.health.govt.nz/maori-health/te-tiriti-o-waitangi-framework

Mitchell, V. A. (2017). Diffracting reflection: A move beyond reflective practice. Education as Change, 21(2), 165–186. https://doi.org/10.17159/1947-9417/2017/2023

Moewaka Barnes, H., & McCreanor, T. (2019). Colonisation, hauora and whenua in Aotearoa. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand, 49(Suppl. 1), 19–33. https://doi.org/10.1080/03036758.2019.1668439

Mutu, M. (2018). Behind the smoke and mirrors of the Treaty of Waitangi claims settlement process in New Zealand: No prospect for justice and reconciliation for Māori without constitutional transformation. Journal of Global Ethics, 14(2), 208–221. https://doi.org/10.1080/17449626.2018.1507003

Mutu, M., Tawhai, V., Cook, T., & Hynes, S. (2021). Dreaming together for constitutional transformation. Counterfutures, 12, 37–52. https://doi.org/10.26686/cf.v12.7720

New Zealand Psychologists Board. (2018). Core competencies for the practice of psychology in Aotearoa New Zealand. https://psychologistsboard.org.nz/wp-content/uploads/2023/08/Core_Competencies.pdf [PDF]

New Zealand Royal Commission on Social Policy. (1988). The April report: Report of the Royal Commission on Social Policy (Volume 1). Wellington, New Zealand.

Ngawati, R., Valentine, H., & Tassell-Matamua, N. (2018). He aha te wairua? He aha te mauri? Ngā Pae o te Māramatanga. https://www.maramatanga.ac.nz/media/5006/download?inline

NiaNia, W., Bush, A., & Epston, D. (2016). Collaborative and indigenous mental health therapy. Routledge.

NiaNia, W., Bush, A., & Epston, D. (2025). Ngā kūaha. Routledge.

Nikora, L. W. (2007). Maori and psychology: Indigenous psychology in New Zealand. In A. Weatherall, M. Wilson, D. Harper, & J. McDowall (Eds.), Psychology in Aotearoa/ New Zealand (pp. 80–85). Pearson Education New Zealand.

Palaganas, E. C., Sanchez, M. C., Molintas, M. V. P., & Caricativo, R. D. (2017). Reflexivity in qualitative research. The Qualitative Report, 22(2), 426–438.

Papps, E., & Ramsden, I. (1996). Cultural safety in nursing: The New Zealand experience. International Journal for Quality in Health Care, 8(5), 491–497.

Pitama, S., Robertson, P., Cram, F., Gillies, M., Huria, T., & Dallas-Katoa, W. (2007). Meihana model: A clinical assessment framework. New Zealand Journal of Psychology, 36(3), 118–125.

Prilleltensky, I., & Prilleltensky, O. (2003). Towards a critical health psychology practice. Journal of Health Psychology, 8(2), 197-210. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105303008002659

Ramsden, I. (2002). Cultural safety and nursing education in Aotearoa and Te Waipounamu. [Unpublished PhD thesis]. Victoria University of Wellington. https://www.iue.net.nz/wp-content/uploads/2024/01/RAMSDEN-I-Cultural-Safety_Full.pdf [PDF]

Reid, M. J. (2011). Good governance: The case of health equity. In V. M. H. Tawhai & K. Gray-Sharp (Eds.), Always speaking: The Treaty of Waitangi and public policy (pp. 35–48). Huia Publishers.

Savolainen, J., Casey, P. J., McBrayer, J. P., & Schwerdtle, P. N. (2023). Positionality and its problems: Questioning the value of reflexivity statements in research. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 18(6), 1331–1338. https://doi.org/10.1177/17456916221144988

Smith, L. T. (1999). Decolonizing methodologies: Research and indigenous peoples. Zed Books.

Snooks, M. (2009). Health psychology: Biological, psychological, and sociocultural perspectives. Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Stewart, M. (2024). Development of a new Code of Conduct and Code of Ethics for Psychologists Working in Aotearoa New Zealand. New Zealand College of Clinical Psychologists. https://www.nzccp.co.nz/about-the-college/rules-and-code-of-ethics/development-of-a-new-code-of-conduct-and-code-of-ethics-for-psychologists-working-in-aotearoa-new-zealand-current-status-and-next-steps/

Sue, D. W., Bernier, J. E., Durran, A., Feinberg, L., Pedersen, P., Smith, E. J., & Vasquez-Nuttall, E. (1982). Position paper: Cross-cultural counseling competencies. The Counseling Psychologist, 10(2), 45–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000082102008

Te Whatu Ora. (2024). The Grand Round research symposium June: Introduction to cultural safety, cultural competency and hauora Māori. Te Whatu Ora News and Updates. https://www.tewhatuora.govt.nz/corporate-information/news-and-updates/the-grand-round-research-symposium-june-introduction-to-cultural-safety-cultural-competency-and-hauora-maori

Tolich, M. (2002). Pākehā “paralysis”: Cultural safety for those researching the general population of Aotearoa. Social Policy Journal of New Zealand, 19, 164–178. https://msd.govt.nz/documents/about-msd-and-our-work/publications-resources/journals-and-magazines/social-policy-journal/spj19/19-pages164-178.pdf [PDF]

Torry, B. (2005). Transcultural competence in health care practice: The development of shared resources for practitioners. Practice, 17(4), 257–266. https://doi.org/10.1080/09503150500426032

Valentine, H., Tassell-Mataamua, N., & Flett, R. (2017). Whakairia ki runga: The many dimensions of wairua. New Zealand Journal of Psychology. 46(3), 64–71. https://www.psychology.org.nz/journal-archive/Whakairia-ki-runga-private-2.pdf [PDF]

Waitangi Tribunal. (2014). Te Paparahi o Te Raki Stage 1 Report (Report No. Wai 1040). https://www.waitangitribunal.govt.nz/en/inquiries/district-inquiries/te-paparahi-o-te-raki-northland

Waitangi Tribunal. (2018). WAI 2725 #1.1.1, The Psychology in Aotearoa Claim: Statement of Claim. https://forms.justice.govt.nz/search/Documents/WT/wt_DOC_137601631/Wai%202725%2C%202.1.001.pdf [PDF]

Waitangi Tribunal. (2022). Te Paparahi o Te Raki Stage 2 Report (Report No. Wai 1040). https://www.waitangitribunal.govt.nz/en/inquiries/district-inquiries/te-paparahi-o-te-raki-northland

Waitoki, W. (2012). The development and evaluation of a cultural competency training programme for psychologists working with Māori: A training needs analysis [Unpublished PhD thesis]. University of Waikato. https://researchcommons.waikato.ac.nz/server/api/core/bitstreams/f3c39c4c-9c6d-4e75-84f5-ce0c4a859fbf/content

Waitoki, W. W., Feather, J. S., Robertson, N. R. & Rucklidge, J. (Eds.). (2016). Professional practice in psychology in Aotearoa New Zealand (3rd ed.). New Zealand Psychological Society.

Waitoki, W., Rowe, L., Brittain, E., Clifford, C., & Skirrow, P. (2024b). Marginalisation, migration, and movement: Responding to the underrepresentation of Māori in the clinical psychology workforce in Aotearoa New Zealand. Manuscript submitted for publication.

Waitoki, W., Tan, K. H., Stolte, O. E. E., Chan, J., Hamley, L., & Scarf, D. (2023). Four decades after a ‘whiter shade of pale’: An update on professional psychology programme responsiveness to indigenous Māori in Aotearoa New Zealand. New Zealand Journal of Psychology, 52(2), 4–14. https://hdl.handle.net/10289/16916

Waitoki, W., Tan, K., Hamley, L., Stolte, O., Chan, J., & Scarf, D. (2024a). Systemic racism and oppression in psychology: Voices from psychologists, academic staff, and students. WERO and University of Waikato. https://researchcommons.waikato.ac.nz/entities/publication/fea1f10e-20f1-4fa9-9ad2-71457f47698a

Watt, D. (2007). On becoming a qualitative researcher: The value of reflexivity. Qualitative Report, 12(1), 82–101. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ej800164

Wear, D., Zarconi, J., Garden, R., & Jones, T. (2012). Reflection in/and writing: Pedagogy and practice in medical education. Academic Medicine, 87(5), 603–609. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31824d22e9

- Our writing is informed by our experience of teaching professional practice skills and cultural safety with Masters students in health psychology. We acknowledge the whakapapa of the frameworks we discuss, as well as our previous work and conversations with our tuakana, Chloe Parton and Denise Blake. Ka nui te mihi ki a kōrua. ↵

A healthcare approach that focuses on recognising, respecting, and responding to the cultural identity of patients, and addressing power imbalances in the healthcare encounter.

The process of critically examining one's own role and assumptions. This means exploring how your values and social positions shape your knowledge production, from project conceptualisation through to analysis. Reflexivity can occur at multiple levels, including your values; positions of privilege and marginality; methodological, theoretical, philosophical, political, or disciplinary assumptions or commitments; and your hopes, expectations, anxieties and fears for your work.

Te reo Māori text of the treaty signed in 1840 between the British Crown and Māori, referred to as the founding document of Aotearoa New Zealand as a nation. Discussed in detail in Chapter 1.1.

The pursuit of a fair and equitable society in which all people have equal access to rights, resources, and opportunities, regardless of their raced, gendered, classed positions, ability, sexuality, and so forth. Social justice moves beyond a focus on rights, by challenging power imbalances, and questioning the systemic barriers to health and structural causes of health inequities.

Person seeking wellness (plural: tāngata whai ora).

A concept developed by Paulo Freire that refers to the process of becoming critically aware of social, political, and economic injustices, and recognising one’s capacity to challenge and change them. Through dialogue and reflection, people develop a deeper understanding of how power and oppression shape their lives—moving from passive acceptance to active transformation of their world. Conscientisation is central to critical pedagogy and liberation psychology. Reference: Freire, P. (2000). Pedagogy of the oppressed (30th Anniversary edition). Bloomsbury.

Chief, leader.

Referring to governance, as a provision of Article 1 of Te Tiriti o Waitangi.

Independence, self-determination, sovereignty; referring to independence, as a provision of Article 2 of Te Tiriti o Waitangi.

A New Zealander of European descent, often a form of positive identification in relation to te ao Māori.

Māori customs and correct processes.

Spiritual authority or power.

A state of restrictedness, sacredness.

Ordinary state, to be free from the restrictions of tapu.

The Declaration of Independence, signed in 1835, declaring the independence of rangatira and asserting Aotearoa New Zealand as an independent state.

A Māori term for non-Māori people living in Aotearoa New Zealand.

Ancestors.

A kinship group or subtribe, comprised of a number of whānau (family) and sharing a common ancestor; section of an iwi (tribe) and the primary political unit in traditional Māori society.

Extended Māori kinship group, tribe, nation; a large group of people descended from a common ancestor and associated with a distinct territory, usually comprised of a number of hapū (subtribes).