2.2 Making sense of bodily experiences: Interpreting signs and symptoms

Tracy Morison and Ally Gibson

Overview

This chapter is about how people make sense of the changes experienced in their bodies as an indication of illness. How do we know when a physical sensation is serious or just a fleeting discomfort? Deciding whether to seek medical care or ignore a symptom is a daily reality, but the process of interpreting bodily signals is far more complex than it might seem. By the end of this chapter, you will be able to understand symptom interpretation as more than a straightforward process. Instead, you will see it as a complex, socially negotiated act with significant implications for individual health, healthcare practices, and broader public health outcomes.

Learning objectives

By the end of this chapter, readers will be able to:

- Articulate the significance of studying symptom interpretation, highlighting its relevance for understanding health and illness experiences.

- Discuss how social meanings shape views of the body and explain the body’s central role in interpreting symptoms.

- Differentiate between key approaches to studying symptom interpretation in health psychology, identifying their strengths and limitations.

- Apply a critical perspective to symptom interpretation by:

- Explaining how symptom interpretation is influenced by social, cultural, and contextual factors.

- Using core concepts to analyse and understand real-world health issues.

Introduction

Deciding whether a physical sensation is a sign of illness that requires medical attention or something that can be shrugged off is a routine part of daily life. It is an experience everyone is familiar with—those moments of wondering, “Is this something serious or just a passing ache?” But why, you might ask, is studying how people interpret these bodily sensations important? To answer that question, let us turn to the following memorable—and humorous—short film, “Just a little heart attack” from a U.S. health campaign. The film was intended “to educate women about the realities of heart disease” (American Heart Association, 2012), including recognising when they are having a heart attack.

This short film highlights that many women have missed the signs and risks of heart attacks, which can manifest differently for (cisgender) women and some (cisgender) men (Zbierajewski-Eischeid & Loeb, 2009). Consequently, women have suffered heart disease invisibly over much of the past century. Indeed, an analysis of the UK National Heart Attack Register in 2016 showed that women are twice as likely to receive a wrong diagnosis for a heart attack than men (Wu et al., 2018).

Our example of misrecognising a heart attack highlights the importance of understanding how individuals interpret their bodies’ signals and the implications for timely medical care. Symptom interpretation can be a life-and-death matter. How people make sense of and then respond to bodily changes (or not) has a bearing on many aspects of maintaining good health, such as seeking medical care, treatment adherence, and self-management of symptoms (particularly for chronic conditions) (Scott & Walter, 2010). Early identification, reporting, and proper attribution of symptoms can facilitate effective treatment for many health conditions (Ginsburg et al., 2020; Lyons & Chamberlain, 2006).

This chapter highlights the important role of social meanings in people’s interpretation and communication of bodily experiences, like those involved in coronary heart disease. Having established how socio-cultural factors shape understandings of health and illness in the preceding chapter (Chapter 2.1), we base this chapter on the premise that symptom interpretation is not just a personal experience but deeply shaped by social meanings and cultural norms. We begin by discussing the body as the central site of health and illness, as “speaking” through signs and sensations, such that symptom interpretation involves a complex interplay between the biological and the social. We then explore how people decipher these bodily signs as symptoms of illness within their specific cultural and social contexts, viewing symptom interpretation as both embodied and culturally situated. As part of this discussion, we critically evaluate traditional and emerging approaches to studying symptom interpretation, recognising their limitations and applying a socially embedded perspective to real-world health issues.

The body that “speaks”: bodies, social meanings, and symptom interpretation

Our bodies communicate through sensations, which we may interpret as signs of illness (Radley, 2004). Far from being neutral or purely biological entities, bodies are imbued with meanings shaped by social, cultural, and political contexts (Barker, 2010; Lupton, 2012). As Corbin (2003, p. 258) noted, “The body speaks to the person through sensations that are anchored in meaning. The meaning is derived through experience in the social world.” These meanings, in turn, influence how individuals understand their bodily sensations and how others—such as family, friends, or healthcare professionals—respond to their symptoms (Gibson et al., 2017).

Historically, medicine and psychology have treated the body as an object, often using the White male body as the standard for health and anatomy (Rosenfield & Faircloth, 2006; Watson, 2000). (This is the “mythical norm” discussed in Chapter 1.2). This objectification has focused on understanding the body in terms of biological components like genes, cells, and muscles, presenting them as objective and universal truths (Ussher, 2006). However, this biomedical perspective often ignores how social and cultural contexts shape how bodies are understood by individuals and society. In contrast, from a critical health psychology perspective, the body can be seen as a “text” that conveys meanings and ideas. These meanings are not inherent to individual bodies but arise from broader societal norms and values that are constantly shifting and open to contestation (Burns, 2004). For instance, a thin body may be associated with health and attractiveness in some cultures, while in others, it might signal frailty or deprivation. These socially constructed meanings influence not only how people view their own bodies and interpret bodily signs and potential symptoms of illness, but also how others respond to the symptoms people communicate (Gibson et al., 2017).

Complementing and expanding on this perspective, embodiment theory proposes that bodies are central to how we experience and interact with the world. Bodies are not merely physical objects but dynamic entities shaped by ongoing interactions with sociocultural contexts (Lyons, 2009; Lyons & Chamberlain, 2017; Ussher, 2008). This interaction is illustrated by the example of coronary heart disease at the start of this chapter. This example highlights how societal norms about gender and pain shape symptom interpretation. The interplay between the social and the biological is further evident across generations. For instance, colonisation in Aotearoa New Zealand (historical and ongoing) has left enduring legacies for the Indigenous Māori, including land loss and associated trauma, which have been linked to poorer health outcomes (Thom & Grimes, 2022). (See Chapter 1.1 for further discussion.)

These examples show how historical, social, and cultural forces shape the meanings attached to bodily signs and, consequently, how symptoms are understood, communicated, and acted upon. Symptom interpretation can, therefore, be thought of as reading or interpreting bodily signs. For example, pain or discomfort signals potential issues that require attention, such as a headache that might indicate dehydration, stress, or a more serious condition.

It is important from the outset to note an important distinction between bodily signs and illness symptoms (Radley, 1994; cf. Kugelman, 2003). These terms are often used interchangeably but have distinct meanings in health psychology and medicine more broadly (see Textbox 1).

Textbox 1. “Sign” versus “Symptom”

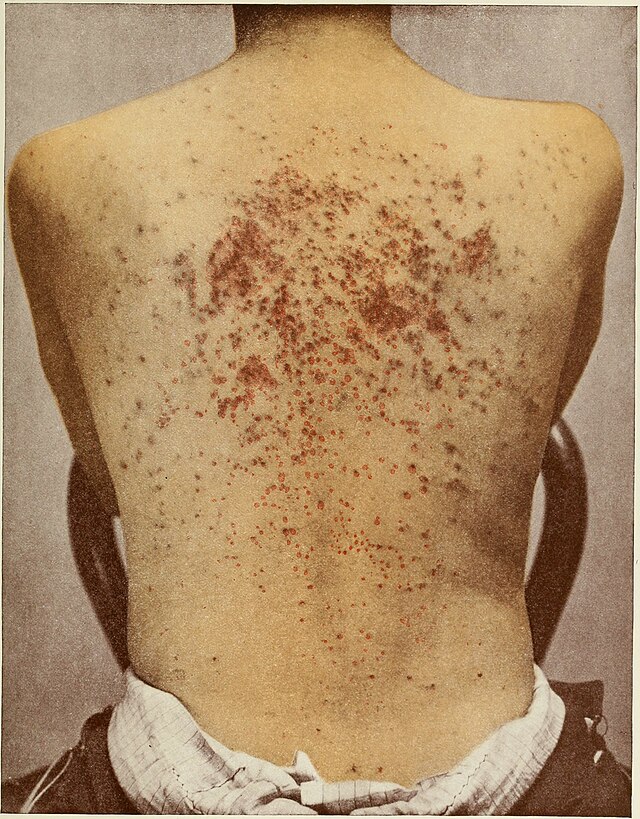

A sign is a change in the body that can be seen or measured, like a rise in temperature or the appearance of aberrant growths, and is considered objective evidence of disease.

A symptom, on the other hand, deals with the experiential aspect, the subjective experience of something out of the ordinary that an individual needs to make sense of (Saddock & Saddock, 2008).

For example, someone may have bodily signs that include red, scaly, inflamed skin, with oozing and crusting lesions. These bodily changes might be experienced as symptoms of itching, sensitivity, irritability, and trouble sleeping. Reporting these to a health provider might result in a diagnosis of eczema.

Thus, put simply, signs are like the visible “evidence” of an issue, while symptoms are the experience of that issue. Both dimensions are involved in figuring out what may be happening with one’s body.

Deciphering “the language of body”: from signs to symptoms

Making sense of the bodily changes they experience is how people arrive at the perception of being well or ill (Corbin, 2003). The fundamentally embodied nature of the process of deciphering the body’s language is well captured by Corbin (2003, p. 265):

Construction of an illness begins with the advent of strange sensations or a change in appearance that can’t be anchored [to] meaning. It’s not the usual sensations caused by stresses and strains of living, like having a sore throat, knee, or elbow that one knows will hurt for a while, then the pain will go away on its own. These sensations are different. The familiar body becomes the unfamiliar body. There follows a period of watching, waiting to see what happens.

Corbin’s description conveys the personal meaning making involved in making sense of unusual or disruptive bodily experiences, depicting what health psychologists traditionally termed “symptom perception.” What it fails to capture, however, is how this process happens within a particular socio-cultural setting in which bodies and bodily experiences, like pain, are imbued with different meanings that inform people’s sense making. The process is about more than just perception; it also involves interpretation.

Critical health psychology has therefore expanded the focus to consider symptom interpretation—as we have approached it in this chapter. We discuss each of these approaches—symptom perception and symptom interpretation—in turn.

Symptom perception

Traditionally, health psychology focused on symptom perception using social cognitive theory, with explanatory frameworks such as cognitive labelling and attribution theory (Head et al., 2022; Phillips et al., 1999). This work is strongly based on social psychology’s perceptual or cognitive perspective and aligns with an individualistic view of the person. (See Chapter 1.2 for a fuller discussion.) From this perspective, people are seen as privately or independently determining whether a certain sign means they are sick, and whether to go to the doctor or to treat themselves based on their own bodily experiences or what they observe others doing (Radley, 1994).

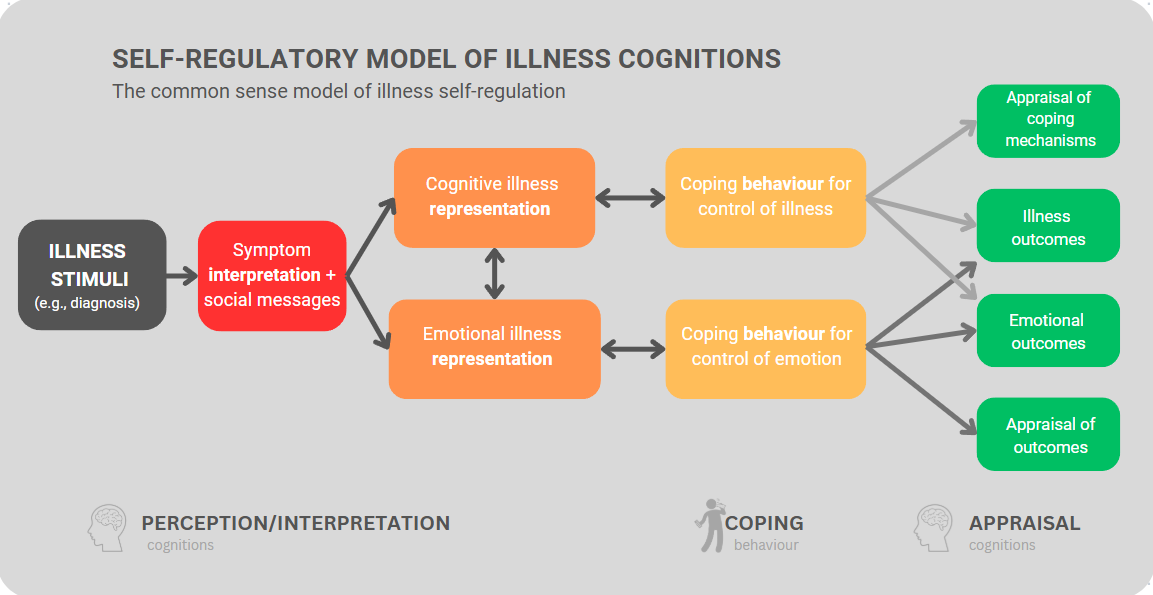

An example is Leventhal, Nerenz, and Steele’s (1984) cognitive model of self-regulation, pictured in Figure 2.2.2. In this model, bodily signs are processed as information by a person (“the perceiver”), who cognitively appraises possible causes and whether the sign indicates a potential risk or threat. Based on this cognitive process, the person may or may not see the bodily changes as a problem, and this perception will then influence whether the person tries to treat it or seek help or medical care.

As this example shows, cognitively based symptom perception models focus largely on solitary thought processes and individual factors. These include differences in “attributional styles” (i.e., how people typically respond to negative experiences affecting them), personality attributes (e.g., neuroticism, optimism), or individual biological differences (e.g., pain sensitivity). More recent models acknowledge factors external to the person, such as how social modelling or media influence the perception and interpretation of symptoms (Gastgeiger & Petrie, 2022). Overall, the primary focus remains cognitive; the goings on inside an individual’s mind is the main explanatory factor for how someone responds to bodily changes potentially signifying illness.

This individual-focused approach—which is dominant in psychology—has been described as “cognitive algebra”: a mental process whereby the person considers different pieces of information based on how important or valuable they appear. The information is then weighed or calculated to reach a final judgment or assessment (Stainton Rogers, 2012). Essentially, it is as though one’s brain is doing mathematics to determine what one thinks about something based on the information available. Particular kinds of thoughts then cause a particular behaviour, like going to a doctor for a diagnosis or ignoring the problem and hoping it will resolve itself. Such a cognitive process may indeed occur, but this is only part of the picture.

In the interests of generating more holistic explanations, critical health psychologists have argued that “explanations which rely upon individual decision-making are actually missing crucial aspects of what happens when people try to determine whether they are, or someone else is, ill” (Radley, 1994, p. 4). Approaches focused solely on what transpires “inside people’s heads” overlook the context in which health-related behaviours occur, including the interconnected nature of people and how they manage their health (Head, Bute, & Ridley-Merriweather, 2021). Therefore, cognitively focused explanations of symptom perception have been critiqued as insufficient to capture the nuance and complexity of how people make sense of their bodily experiences.

Symptom interpretation

Critical health psychologists—along with scholars from disciplines like medical sociology and anthropology—argue that making sense of bodily changes is much more complex than simply perceiving them. It is more akin to a process of interpretation in that people assign meaning to information or experiences based on individual perceptions, cultural beliefs, and contextual factors within social relationships (Head et al., 2022; Nettleton, 2020). Consider the following illustrative scenarios in Textbox 2, for example.

Textbox 2. Symptom interpretation involves individual perception and contextual factors

Scenario 1: Mei and Aisha are dealing with the aftermath of going on a hike. Mei, raised in a traditional Chinese family, smiles tightly and dismisses her sprained ankle as a minor nuisance. “No need to fuss,” she tells Aisha stoically. Meanwhile, Aisha, hailing from a Western background, expresses concern, urging Mei to seek medical attention for her injury. Mei begins to feel a bit concerned when Aisha recounts her own experience of leaving an injury untreated, allowing Aisha to take her to the clinic.

Scenario 2: Michael, a middle-aged British construction worker, wakes up feeling unusually fatigued and short of breath. Despite experiencing persistent chest pains over the past week, he dismisses them as mere discomforts of his physically demanding job. “I’ll tough it out,” he mutters, unwilling to acknowledge any vulnerability or weakness. Concerned about Michael, his partner eventually persuades him to see a GP. He reluctantly agrees, “just to make her happy”.

These scenarios show different meanings assigned to bodily signs according to cultural and gender norms, and hence different responses to these.

In the first scenario, Mei and Aisha demonstrate cultural differences in pain perception, where suffering is more than bodily sensations and reflects deeply held cultural beliefs. Mei remains resolute, adhering to cultural norms that valorise endurance and self-sacrifice (Lewis et al., 2023). The second scenario highlights gendered cultural norms. Adhering to Western norms that equate certain kinds of masculine performance with stoicism and discourage expressions of vulnerability or reliance on others, Michael interprets the sensations in his body as “normal” fatigue or strain from manual labour rather than signs of illness. Michael’s failure to seek medical care draws attention to the enduring pressure on men to “harden up” and embody traits of endurance and self-reliance, and a tendency of some men to treat their bodies as machines. We may also note how men’s interactions with health services are shaped by gender norms, as their engagement is sometimes facilitated through their female partners (Anstiss & Lyons, 2014; Noone & Stephens, 2008; Seymour-Smith, Wetherell, & Phoenix, 2002).

Note about use of names[1]

These examples highlight how personal and social meanings become attached to bodily sensations. The socio-cultural context thus plays a pivotal role in shaping people’s interpretations and responses to bodily sensations, influencing what is deemed bearable and acceptable regarding pain expression and subsequent help-seeking behaviours (Radley, 1994; Kugelmann, 2017; Rosendal et al., 2013). Critical health psychologists, therefore, consider the process by which people recognise and interpret physical sensations in their bodies as signs of illness as (1) embedded in the social context and (2) negotiated with others (relational), as we discuss next.

Symptom interpretation as socially embedded

When people make sense of unusual sensations like fatigue, pain, or shortness of breath, they draw on their knowledge about sickness, including its bodily signs. This knowledge is connected to people’s socio-cultural settings and social identities, which comprise intersecting social categories (e.g., race, ethnicity, social class). There are also cultural expectations about which bodily disturbances require medical attention and which are considered “normal” (as discussed above). These cultural expectations thus guide as to when advice should be sought from others and extend to norms specifying how to present illness to others or ask for treatment (Brandner et al., 2014; Hay, 2008; Radley, 1994).

A good example of this is pain. Pain is a complex phenomenon that cannot be understood solely in biomedical terms, as its perception is impacted by socio-cultural, emotional, and cognitive factors (Kugelmann, 2003, 2016; Perović et al., 2021; Prakash, 2020). The following case study offers a powerful illustration of how cultural and gender norms shape the interpretation and expression of pain. It involves a group of Somali-Canadian women who had undergone female genital cutting—a culturally specific and deeply gendered practice. While this context may be unfamiliar or confronting for some readers, the case offers important insight into how pain is socially mediated, and how cultural frameworks shape not only the experience but also the interpretation and communication of pain.

Textbox 3. “Are you in pain if you say you are not? Accounts of pain in Somali-Canadian women with female genital cutting” (Perović et al., 2021)

A mixed methods study was conducted with 14 Somali-Canadian women who had the most extensive form of female genital cutting. The researchers collaborated closely with members of the Toronto Somali community through a Community Advisory Group that guided all stages of the research, including recruitment, interview design, and cultural considerations. Although the researchers were not themselves Somali, this partnership ensured the research was community-informed and culturally sensitive.

The researchers hypothesised that female genital cutting[2] would cause neural changes that could lead to chronic neuropathic pain. Although quantitative sensory testing[3] showed pain thresholds similar to those of women with chronic vulvar pain, participants reported no or low levels of pain when completing standardised questionnaires and when asked directly about pain in general terms. For example, they said things like, “My body feels fine” or “I don’t have a pain naturally anywhere in my body…I just feel good”, describing themselves as “good”, “healthy”, and “happy”. However, in other parts of the interview—especially when discussing specific activities like menstruation, intercourse, or daily movement—they described considerable and sometimes debilitating pain. This apparent contradiction reflects how cultural norms around stoicism, womanhood, and the meaning of “pain” can shape when and how pain is acknowledged.

The researchers interpreted this discrepancy between the physical sensations and the women’s experiences of it as related to the cultural normalisation of pain, especially women’s pain. In Somali culture, stoicism in the face of pain is highly valued, and children are taught from a young age to control pain expression. Labelling oneself as being in pain typically signals a need for urgent help, and endurance is associated with strength. The researchers state, “The women in our study may have conceptualised pain this way, explaining their insistence on not being in pain, despite reporting specific instances of pain in everyday life”. Consequently, women with female genital cutting see expressing pain, including during the original female genital cutting procedure as well as later (i.e., during childbirth), as shameful and express pride in their resilience.

It may also be that when participants describe themselves as feeling “fine” and deny being in pain, they are accepting pain as a normal part of womanhood. In their culture, Somali women who have experienced female genital cutting recognise it as a rite of passage to womanhood and believe that womanhood itself involves pain. This is expressed in the poem by Dahabo Musa cited by Perović et al., (2021):

My grandmother called it the three feminine sorrows. The day of circumcision, the wedding night, and the birth of a baby […] They say, it is only feminine pain, and feminine pain perishes.

These words strikingly capture the cultural normalisation, and subsequent minimisation, of Somali women’s pain.

The experiences of these Somali-Canadian women undergoing female genital cutting vividly demonstrate that symptoms are not simply objective phenomena. Rather, as the example above illustrates, they are multidimensional constructions in which biological sensations may appear as symptoms, and weaken or intensify in response to various social and cultural contexts and psychological processes, as highlighted by cross-cultural and anthropological studies (Rosendal et al., 2013).

The case study demonstrates the complex nature of how bodily sensations are assigned meaning, showing how the process is socially patterned and shaped by what a symptom may signify. Responses such as worry, fear, or care—or the opposite—are therefore culturally based and fall under the category of “expected” emotions (Radley, 1994). In the case of the Somali-Canadian women, these include endurance and presenting oneself as “happy” and “healthy” despite pain sensations. Intersecting cultural and gender norms guide what women (and men) consider tolerable in terms of pain and when or whether it is acceptable to complain or to seek help or treatment. These findings are consistent with broader research highlighting disparities in pain experiences between genders (e.g., Jaworska & Ryan, 2018; Radley, 1994) and the impact of cultural norms and socialisation patterns (e.g., Lewis et al., 2023; Morunga et al., 2024; Upsdell et al., 2024).

These studies also emphasise the interconnectedness of social categories such as culture, gender, and social class in shaping health experiences and symptom interpretation. Such findings are not unique to particular cultural groups, like Somalis. Across different settings—including both Somali-Canadian and Western working-class contexts—pain may be normalised in ways that reflect broader expectations of gender, class, and cultural endurance. For example, like the women in Perović et al.’s (2021) study, working-class women in Western contexts may be more likely than middle-class women to view pain as something to be endured rather than treated—especially pain related to menstruation, childbirth, or caregiving. This reflects intersecting systems of gender, class, and, in some cases, race and migration status, which normalise women’s suffering and shape access to care (Fang, 2023; Johansson et al., 1999; Rice, Connoy, & Webster, 2024). Such findings show that “pain cannot be reduced to a sensory state to be explained by the medical profession: it needs to be understood at the nexus of affective, psychological, social and communicative practices of people-in-pain” (Jaworska & Ryan, 2018, p. 107).

It is important to point out that the findings discussed above are not simply the result of suppressed responses (i.e., ignoring real pain), self-deception, or misinterpretation of bodily signs. Rather, how bodily changes are understood often shapes the bodily experience itself. This is evident, for instance, in cultural understandings about menopause, which “have a significant influence on women’s experience of embodied change at midlife” (Ussher, 2008, p. 1786). Cross-cultural anthropological research shows geographical variation in both the symptoms that women report during menopause and the diseases that may subsequently develop. Japanese women, for example, are much less likely than North American women to have most of the symptoms that medicine commonly associates with menopause (Lock, 1994; Lock & Kaufert, 2001). (Recall also the example of premenstrual syndrome in the previous chapter; this condition shows similar cross-cultural patterns, such that the condition can be considered a culture-bound syndrome.)

Making sense of these cross-cultural differences, anthropologist Lock (1998) showed how bodily feelings and reported symptoms are shaped by people’s subjective experiences, which are based on culturally informed knowledge, expectations, and practices. In Euro-American and other Western contexts, a dominant “biomedical deficiency discourse” (Ussher, 2008, p. 1785) frames menopause as a disease requiring medical treatment, focusing attention on the biological aspects. It is commonly portrayed negatively: ranging from an unpleasant sign of old age decline to a hellish time of living decay (Lock, 1998; Perz & Ussher, 2008; Utz, 2010). In contrast, the Japanese have no word for this stage in the life cycle and tend to emphasise social, rather than biological, change in older age. Older women, for instance, remain engaged in childcare, which is considered an extension of their fertility (Hagège, 2020; Lock, 1994).

As in the example of menopause, critical scholars highlight that a culture’s common explanations of bodily changes or symptoms generate a dominant, normative reality; this becomes the framework or lens people use to interpret their own physical sensations (Lyons & Chamberlain, 2006). How bodies and health or illness are portrayed in public discussion, and especially the media, plays an important role. This goes beyond the provision of factually correct information; these public representations mediate and shape how people “hear”, make sense of, and respond to “the language of [the] body” (Corbin, 2003, p. 258).

Social meanings and social reception

The widely accepted meanings of illnesses shape the social reception of particular illnesses in specific contexts—that is, how others respond to people with different conditions (referred to as social reception), sometimes negatively (Gibson et al., 2017; Werner et al., 2004). Some illnesses have better social reception, while other carry social stigma. Although all illnesses represent a deviation from the norm of the healthy, able body, and potentially carry stigma (Radley, 1994); the level of stigma varies. This variation is related to factors like who is seen as responsible for this deviation, whether the illness is contagious, the source of infection, if the illness negatively affects bodily appearance or odour, and so on.

“The difference between illnesses that carry high versus low levels of stigma”, Olafsdottir (2013, p. 43) points out, “illustrates that there is nothing inherent in some conditions that naturally leads to stigma.” Rather, the issue is the social meanings that are associated with different illnesses, such as dirtiness, sexual immorality, laziness, poor self-control, and so on. Let us consider two examples to illustrate this, those of (1) HIV/AIDS and (2) cancer (see Textbox 4).

Textbox 4. Social meanings of illness: shame and blame, responsibility and stigmatisation

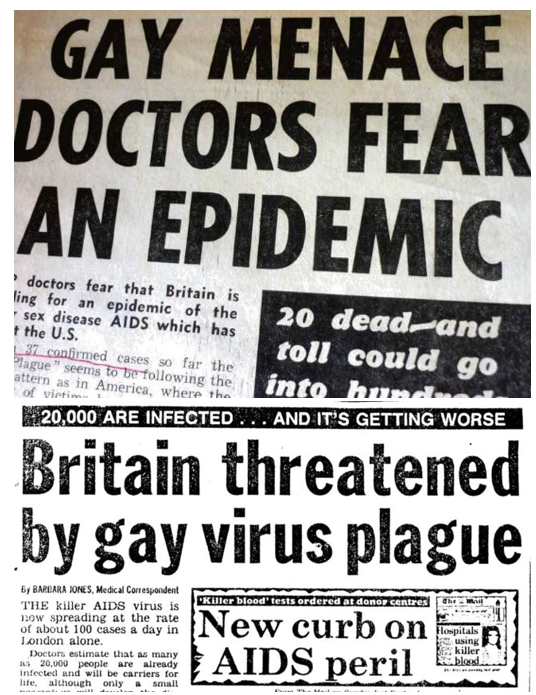

The widespread stigma associated with HIV/AIDS, especially when it was first identified but not well understood in the 1980s and -90s, offers a striking example of how illnesses become stigmatised. Globally, the medical narrative of AIDS was linked to sexuality, particularly homosexuality. In fact, the condition was even referred to as “gay-related immune deficiency” (GRID), until it became apparent heterosexual people were also being infected. The condition was widely characterised as a “homosexual disease” or more pejoratively, as shown in the newspaper headlines below.

This misconception fuelled widespread panic and prejudice, isolating those affected and further marginalising an already vulnerable social group. In Australia, a 2022 national enquiry found that media coverage of the early years of the HIV epidemic contributed to the high level of violence against gay men and lesbians, particularly a 1987 “AIDS awareness” television advertisement featuring the Grim Reaper, which appears below (McKinnell, 2022). The stigma also hindered public health efforts, delaying effective responses and exacerbating the epidemic due to reluctance to seek testing and treatment (Tsampiras, 2008, 2014).

Cancer is not similarly reviled but carries different connotations related to the form of cancer. Gibson et al., (2017, p. 986) explain that “not all cancers are equal—instead, they are a series of illnesses that are varyingly constructed through moral framings and ascribed varying degrees of agency and even individual responsibility”. These researchers conducted a study of Australian women’s experiences of living with cancer and focused on social reception (i.e., how others responded to their disclosures of having cancer). The participants reported that the compassion others showed them depended upon their type of cancer. This “conditional compassion” is linked to assumptions about different forms of cancer and broader cultural norms surrounding the disease (Gibson et al., 2017, p. 991). As part of this, some participants discussed how they were often held to blame for forms of cancer (like lung cancer or cervical cancer) that are associated with “lifestyle choices”, such as diet, smoking, and sexual practices.

For example, a participant diagnosed with lung cancer said, “They tell you [to] stop smoking but I never smoked […] [I] occasionally hear a parent telling their child, ‘See what happens if you smoke?’ … the parents are really ignorant and rude”. Another recounted, “My daughter made a comment to the children … she said, ‘Nan’s got lung cancer, because of the smoking’ …I don’t like to hear it … but she was trying to educate them” (Gibson et al., 2017, p. 987). These findings echo international research and polls of public perceptions of lung cancer. These studies show that owing to lung cancer’s association with smoking, many people tend to blame those with the disease for causing it and feel less sympathy for them (Chapple et al., 2004; Global Lung Cancer Coalition, 2023; Head et al., 2022; Marlow et al., 2015).

The examples of HIV/AIDS and cancer highlight the moral dimension of illness “concerning shame and blame, responsibility and stigmatisation” (Werner et al., 2004, p. 1036). They illustrate the very real consequences resulting from how illnesses are understood and what they signify in certain cultural settings. There are consequences for individuals’ identity and sense of self (Radley, 1994), the likelihood of receiving social support, and even healthcare delivery (Gibson et al., 2017; Tran et al., 2015), which we delve deeper into in Chapter 2.3. Negative and stigmatising responses may discourage screening or help-seeking, worsening the prognosis (Carter-Harris, 2015).

There may also be wider repercussions. Everyone is at risk when infectious diseases cannot be managed effectively due to social stigma, as in the case of the AIDS epidemic and, more recently, the COVID-19 pandemic of 2020. Health inequities can also be widened, as public funding and financing are channelled according to perceptions of deservedness, as seen in the case of cancer (see King, 2012). For example, breast and prostate cancers receive more visibility and funding relative to other forms, like lung cancer (Gibson et al., 2017; Tran et al., 2015). In addition to this, “awareness cultures” have coalesced around certain, more “acceptable” forms of cancer. In the case of breast cancer, for example Pink Ribbon and similar awareness efforts often reinforce highly gendered assumptions about how (cisgender) women with cancer should look and behave in response to their illness (Gibson et al., 2014, 2016). This can have the consequence of alienating or overlooking people who do not fit within the narrow confines of these gendered depictions and expectations (Gibson et al., 2016), exacerbating the challenges that people face in relation to their health.

Symptom interpretation as socially negotiated

The examples provided thus far should make it evident that recognising bodily sensations and interpreting them as symptoms is not something people do in isolation from others (Rosendal et al., 2013). One aspect of this is getting help from others to interpret symptoms. For instance, others can offer advice and help decipher the meaning of an ambiguous bodily sign, such as whether a headache is a sign of a serious medical condition or related to less serious causes like tension, dehydration, eye strain, or caffeine withdrawal. This kind of communication involves gauging one’s experience against the views or experiences of others (Head et al., 2022; Rosendal et al., 2013).

However, critical scholars highlight that symptom interpretation involves more than just exchanging information. People do not just react to someone’s symptoms once they are disclosed; they also have a major impact on how physical signs come to be seen as “real” symptoms warranting medical treatment (Kugelmann, 2016; Radley, 1994). Determining “whether one is or is not ‘really ill’ is often a matter of social negotiation” (Radley, 1994, p. 78).

This negotiation is perhaps very familiar to those who have ever attempted to be allowed to stay home from school due to illness. In fact, this scenario offers a simple but effective way of explaining the social mediation involved in symptom interpretation, essentially, whether others recognise one’s symptoms as a legitimate sign of illness. For example:

Priya nervously approaches her parents, clutching her stomach and putting on a tired, feeble voice. “I don’t feel well,” she says, rubbing her forehead as if checking for a fever. She knows the school swimming gala is today, and she wants to avoid it without disappointing her classmates. Claiming to be sick seems like the perfect excuse, but she has to make it convincing. She slows her movements, pretends to struggle to eat breakfast, and coughs faintly, trying to match her symptoms to what she imagines will appear believable. Priya’s goal is simple: secure a sick note and stay home guilt-free.

This familiar scenario illustrates how symptoms are presented and enacted for others, and the importance of others’ responses. It highlights three core concepts in the social negotiation of symptom interpretation, namely: (1) the sick role, (2)social sanctioning, and (3) credibility work.

The sick role

Presenting symptoms to others involves making a claim to be ill and thereby being allowed to take up and benefit from what is termed “the sick role”, in this instance, the benefit of being able to stay home from school. The concept of the sick role was first proposed by sociologist Talcott Parsons (1975) and is explained in more detail in the CrashCourse clip below (watch until the 6:02 time mark). This concept has since been developed, but the basic idea remains useful.

Social sanctioning

Since illness has significant social consequences, bodily sensations must be sanctioned as symptoms by society. Essentially, others must agree that one is indeed ill (Rosendal et al., 2013). How others respond plays a significant role in seeking help and receiving care and support. So, just as the child in our example presents her symptoms to her parents, so symptoms are presented and enacted for others. Like the parents in our example, these others are often authority figures with the power to act as gatekeepers to care and resources (Head et al., 2022; Rosendal et al., 2013).

Credibility work

The concept of credibility work describes the efforts people make to convince others that their symptoms are legitimate and warrant medical attention. As in the case of the school child having to put on a believable show of being unwell, those who claim to feel unwell must perform in particular ways to legitimise their illness and be permitted the sick role (Kugelmann, 2000; Werner et al., 2003). Being allowed the sick role and exempted from social responsibilities, like going to school, relies on having the presentation of one’s symptoms confirmed and believed by others (Rosendal et al., 2013). “The degree to which a person’s experience of illness is accepted by his or her surroundings is tied to … the degree in which it becomes socially meaningful” (Glenton, 2003, p. 2244). In other words, how people present themselves as ill must be intelligible to others. The ‘‘work’’ done by the ill person to be believed, understood, and taken seriously, or to appear as a credible patient, includes what they say and do, and even their appearance.

Illness narratives are an important aspect of credibility work (Head et al., 2022; Yamasaki, Geist-Martin, & Sharf, 2016; Werner et al., 2004). As Bülow (2008, p. 137) explains:

In the medical encounter, as well as in everyday conversations, illness has to be “storied” to “exist.” The story and in what way it is heard could be the difference between receiving a certain diagnosis or not, or between becoming confirmed or doubted. Unless one tells a convincing story, illness becomes contested.

This is evident in classic analyses of illness narratives. These narratives show how people try to account for their illness experiences in recognisable ways, working to represent themselves as legitimately ill and deserving of care or treatment (Frank, 1995; Murray, 1999).

People who feel ill, therefore, actively engage in relational negotiation and disclosure with other people in their life. Sharing bodily experiences with others is shaped by the roles one occupies and one’s relationships with others. Both are contoured by power relations. This entails “credibility work”— attempts to present to others as a convincing and believable patient—in order to gain “social sanctioning” (Head et al., 2022). For those who fail, there are wide-ranging consequences, particularly if the illness is serious and ongoing, as illustrated by Arementor’s (2017) study of women living with the contested illness of fibromyalgia, described in the case study in Textbox 5 (below). Cases of contested illnesses raise the question of what happens when others do not recognise one’s symptoms as a legitimate sign of illness.

Unintelligible illness: failing to achieve social sanctioning

Individuals who suffer from bodily ailments but fail to gain social acceptance for their suffering often find themselves in a liminal state—experiencing illness but not recognised as “sick.” This lack of recognition can lead to two significant consequences: (1) delegitimation and (2) stigmatisation (Glenton, 2003).

Delegitimation occurs when individuals are denied the “sick role.” Without clear medical evidence or a definitive diagnosis, their illness may lack a name, leading others to question or challenge the legitimacy of their suffering. This denial undermines the person’s right to be seen as ill and, therefore, deserving of support and empathy (Gibson et al., 2017). Dumit (2006, p. 577) describes this as a situation in which “everyone—the patient’s family, friends, health insurance, and in many cases the patient—comes to think of the patient as not really sick and not really suffering.” This social invalidation often leaves individuals feeling that others cannot hear or acknowledge their claims, reducing them to feeling “crazy” rather than legitimately unwell (Armentor, 2017; Åsbring & Närvänen, 2002; Werner et al., 2004).

Conditions classified as “invisible illnesses” (e.g., autoimmune conditions managed through medication) or those with no clear medical explanation (e.g., post-Lyme disease) are particularly prone to this kind of delegitimation. These illnesses are often characterised by uncertainty regarding their causes, diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis, making them “unintelligible” in medical, legal, and popular discourse (Dumit, 2006). As a result, individuals with such conditions struggle to establish their suffering as legitimate or to receive appropriate recognition and care (Armentor, 2017).

Stigmatisation adds another layer of difficulty. Disclosing a contested condition involves considerable risk for the individual. If the person fails to convince others of their credibility and the legitimacy of their illness, their moral character may also be questioned (Åsbring & Närvänen, 2002). In such cases, not only is the illness doubted, but the individual themselves may be viewed as untrustworthy or lacking integrity.

Experiences of delegitimation and stigmatisation compound the social and emotional burden of living with a condition that is already contested and poorly understood, as illustrated in the following case study.

Textbox 5. Social negotiation in action: the example of contested illness

The role of social negotiation in recognising an individual’s symptoms is exemplified in contested illnesses like chronic fatigue syndrome and fibromyalgia. These conditions have partly overlapping symptomatology, including fatigue and exhaustibility, muscle pain and weakness, and sleep difficulties. Both often face stigmatisation owing to their invisible nature, characterised by elusive aetiology, diagnostic uncertainty, and unclear treatment strategies (Armentor, 2017; Åsbring & Närvänen, 2002; Werner et al., 2004). Such indeterminacy can raise questions about the legitimacy and veracity of people’s claims to illness, positioning them in socially devalued ways, such as “hypochondriacs.”

To combat this, people sometimes try to re-establish a valued social identity by modifying what they share with others, to seem as though they are not unwell or not suffering from a stigmatised condition (Head et al., 2022; Plage et al., 2018). This strategic disclosure is illustrated in Armentor’s (2017) research, “Living with a contested, stigmatized illness: Experiences of managing relationships among women with fibromyalgia”. The researcher conducted a qualitative study with 22 US American women diagnosed with fibromyalgia. The participants were asked about how they go about talking about their illness with other people and reactions to their experiences. Participants commonly encountered disbelief from others, for example:

Everybody kept saying, “Oh nothing’s wrong. You’re depressed.” I kept getting, “You’re depressed. You’re depressed.” I was like, “No.” (Diane, p, 467).

It’s very difficult because you look fine. You don’t—nobody sees that there’s anything wrong with you. It’s hard for them to accept that you do have this difficulty. If you have a broken leg, and it’s in a cast, then your family doesn’t expect you to get up, and clean house, and do dishes, and run five miles. When you look perfectly healthy, it’s hard for them to accept that there’s anything wrong with you. In the beginning especially, they don’t understand. Still today, they don’t understand because you look fine. (Brenda, p. 469.)

Armentor (2017, p. 467) concludes that this kind of disbelieving response “reflects the contested nature of the diagnosis among physicians and the general public” (p. 467).

She also asked participants about managing stigma and found that stigmatisation manifested in two ways for them. First, the invisibility of the illness resulted in reputational stigma, with the women’s character being questioned, due to behavioural changes that deviated from societal norms. For instance, activities like napping and reducing social engagements were met with scepticism and distrust. For example:

…when I had my oldest daughter, he [father] would get mad at me because I was sleeping a lot. This was long before I was diagnosed. He was like, “You’re sleeping too much. You’re sleeping too much. You’re sleeping too much.” He would tell me that I was being irresponsible, I was a moron, and things like that. (Marie, p. 468.)

Second, while a diagnosis sometimes alleviated stigma, stigma also intensified in cases where medical practitioners did not recognise the illness, reinforcing scepticism from others. Despite attempts to educate and seek support, scepticism, and lack of understanding often led participants to stop disclosing to others and withdraw from social interactions to avoid the stigma associated with their condition. These responses lead to social isolation and a lack of much-needed support, as the following participant quote shows.

I don’t reach out to anybody; I just kinda suck it up and deal with it on my own. I just kinda shut the world out until it passes … when I’m not feeling good I won’t reach out. Just stay in my own little bubble, basically. (Jennifer, pp. 469-470.)

This case study clearly shows that in addition to the benefits of taking up “the sick role,” there can be negative social outcomes from others knowing about one’s illness. The chance of stigma arises when an illness or condition becomes known to others (Armentor, 2017).

Conclusion

In this chapter, we explored the body as the central site of health and illness, emphasising the culturally situated and relational nature of symptom interpretation. Identifying signs as symptoms involves more than individual judgment; it is a socially mediated process that relies on interactions with others, including family, friends, and medical professionals. Presenting symptoms is a moral claim, seeking validation and treatment from those around us. However, the process is also shaped by the authority and expertise of healthcare providers. As Glenton, (2003, p. 2244) highlights,

In Western society, a key player in the legitimation of illness is the medical doctor, a gatekeeper function that is justified with reference to the medical profession’s ability to identify objective biological or pathological findings, that is, signs of disease.

In the next chapter (Chapter 2.3), we examine how symptom presentation unfolds in healthcare contexts—as an important site of the social negotiation of symptoms— focusing on the diagnostic process as a powerful form of social sanctioning that grants individuals “permission to be ill” (Nettleton, 2006, p. 1167).

Summary of main points

Some key takeaways from this chapter:

- People’s interpretations of bodily changes influence whether they seek medical help or ignore symptoms.

- Bodies carry social meanings that affect how signs are understood and communicated as symptoms.

- Symptom interpretation is not purely individual; it is shaped by social and cultural factors.

- Understanding this complexity can improve interactions with healthcare providers and lead to better health outcomes.

- Traditional health psychology approaches focus on individual decision making, while critical health psychology perspectives highlight social context and cultural norms.

- Recognising symptoms involves negotiation with others who may support or dismiss the individual’s illness claims.

- Lacking a formal diagnosis or visible signs can lead to delegitimation and stigma.

- Social values, norms, and power dynamics (including medical authority) influence how symptoms are interpreted and validated.

- Gender, culture, and social class all affect how symptoms are expressed, perceived, and acted upon.

- A socially embedded view of symptom interpretation helps explain why some conditions are taken seriously while others are doubted.

Learn more

Key scholarship in critical health psychology

- Jane Ussher has written extensively on various issues in Women’s Health Psychology. Her book, Managing the Monstrous Feminine, deals with the issues of regulating women via the body, the production of knowledge about reproduction, and women’s resistance.

- Robert Kugleman is a U.S. American psychologist who has worked on the topic of pain. His open-access book, Constructing Pain, provides a good overview of his work on this topic.

- Alan Radely‘s work has been influential in establishing health psychology. He drew on insights from social psychology to investigate the social and psychological aspects of health and illness. His 1994 book, Making Sense of Illness: The Social Psychology of Health and Disease, can be considered a classic and is very accessible.

Further reading

- Bourke, J. (2014). The story of pain: From prayer to painkillers. OUP Oxford. – An accessible and thought-provoking read for those wishing to explore cultural and historical perspectives on pain in more depth

- Hagège, S. (2020, February 26). Is menopause a social construct? Centre for Scientific Research (CNRS) News; Centre for Scientific Research. https://news.cnrs.fr/articles/is-menopause-a-social-construct

- Lyons, A. C. (2009). Masculinities, femininities, behaviour and health. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 3(4), 394–412.

Multimedia

- Antonia Lyons discusses youth alcohol consumption and touches on its gendered nature in the following podcast.

Documentaries/films

- Unrest (2017): This 97-minute documentary offers a personal look at invisible illness. A form of illness narrative, Barea turns the camera on herself to share her journey of ME (also known as chronic fatigue syndrome), a misunderstood and highly stigmatised disease. [Available to stream free-of-charge on various platforms, including YouTube.)

- TED Talk by Jennifer Brea (2016) “What happens when you have a disease doctors can’t diagnose?” (16:58 mins)

Questions for reflection and discussion

- Explain how symptom interpretation differs according to people’s different social locations (e.g., culture, gender, race, ethnicity, class etc.). Illustrate your answer by referring to one or more illnesses/conditions.

- What is stigma, and how is it relevant to understanding people’s health experiences? To answer this question use an example of a disease or condition (like HIV/AIDS, type II diabetes, or chronic fatigue syndrome).

- Watch Jennifer Brea’s TED Talk about her experience of chronic fatigue syndrome (CFS)/myalgic encephalomyelitis (ME) and discuss the negotiation of symptom interpretation in relation to contested, invisible or medically unexplained illness. Some points to guide your discussion:

- Apply the concepts of credibility work, social sanctioning, and power relations to Brea’s illness narrative, using some example to show these in action.

- Discuss how these dynamics impacted the care Brea received.

- How might awareness of these dynamics in clinical practice change how symptoms are interpreted, negotiated and treated by healthcare providers?

References

Anstiss, D., & Lyons, A. (2014). From men to the media and back again: Help-seeking in popular men’s magazines. Journal of Health Psychology, 19(11), 1358–1370. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105313490314

American Heart Association. (2012, 30 March). Elizabeth Banks in “Just a little heart attack.” [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_JI487DlgTA

Armentor, J. L. (2017). Living with a contested, stigmatized illness: Experiences of managing relationships among women with fibromyalgia. Qualitative Health Research, 27(4), 462–473. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732315620160

Åsbring, P., & Närvänen, A. L. (2002). Women’s experiences of stigma in relation to chronic fatigue syndrome and fibromyalgia. Qualitative Health Research, 12(2), 148–160. https://doi.org/10.1177/104973230201200202

Barker, K. K. (2010). The social construction of illness: Medicalization and contested illness. In C. E. Bird, P. Conrad, A. M. Fremont, & S. Timmermans (Eds.), Handbook of medical sociology (6th ed., pp. 147–162). Vanderbilt University Press.

Brandner, S., Müller-Nordhorn, J., Stritter, W., Fotopoulou, C., Sehouli, J., & Holmberg, C. (2014). Symptomization and triggering processes: Ovarian cancer patients’ narratives on pre-diagnostic sensation experiences and the initiation of healthcare seeking. Social Science & Medicine, 119, 123–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.08.022

Bülow, P. (2008). “You have to ask a little”: Troublesome storytelling about contested illness. In L. Hydén & J. Brockmeier (Eds.), Health, illness and culture: Broken narratives (pp. 137–159). Routledge.

Burns, M. L. (2004) Bodies that speak: Examining the dialogues in research interactions. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(1), 3–18. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp050oa

Carter-Harris, L. (2015). Lung cancer stigma as a barrier to medical help-seeking behavior: Practice implications. Journal of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners, 27(5), 240–245. https://doi.org/10.1002/2327-6924.12227

Chapple, A., Ziebland, S., & McPherson, A. (2004). Stigma, shame, and blame experienced by patients with lung cancer: Qualitative study. BMJ, 328(7454), 1470. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.38111.639734.7C

Corbin, J. M. (2003). The body in health and illness. Qualitative Health Research, 13(2), 256–267. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732302239603

Dumit, J. (2006). Illnesses you have to fight to get: Facts as forces in uncertain, emergent illnesses. Social Science & Medicine, 62(3), 577–590. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.06.018

Facchin, F., Saita, E., Barbara, G., Dridi, D., & Vercellini, P. (2018). “Free butterflies will come out of these deep wounds”: A grounded theory of how endometriosis affects women’s psychological health. Journal of Health Psychology, 23(4), 538–549. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105316688952

Fang, Y. (2023). Factors influencing the perception and management of chronic pain for immigrant women in Saskatchewan: An exploratory qualitative study (Unpublished doctoral dissertation, University of Saskatchewan).

Frank, A. W. (1995). The wounded storyteller: Body, illness, and ethics. The University of Chicago Press.

Gastgeiger, C., & Petrie, K. J. (2022). Symptom perception and interpretation. In G. J. G. Asmundson (Ed.), Comprehensive clinical psychology (2nd ed., pp. 53–63). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-818697-8.00067-4

Gibson, A. F., Broom, A., Kirby, E., Wyld, D. K., & Lwin, Z. (2017). The social reception of women with cancer. Qualitative Health Research, 27(7), 983–993. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732316637591

Gibson, A. F., Lee, C., & Crabb, S. (2014). ‘If you grow them, know them’: Discursive constructions of the pink ribbon culture of breast cancer in the Australian context. Feminism & Psychology, 24(4), 521–541. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959353514548100

Gibson, A., Lee, C., & Crabb, S. (2016). Representations of women on Australian breast cancer websites: Cultural ‘inclusivity’ and marginalisation. Journal of Sociology, 52(2), 433–452. https://doi.org/10.1177/1440783314562418

Ginsburg, O., Yip, C-H., Brooks, A., Cabanes, A., Caleffi, M., Dunstan Yataco, J. A., Gyawali, B., McCormack, V., McLaughlin de Anderson, M., Mehrotra, R., Mohar, A., Murillo, R., Pace, L. E., Paskett, E. D., Romanoff, A., Rositch, A. F., Scheel, J. R., Schneidman, M., Unger-Saldana, K., … Anderson, B. O. (2020). Breast cancer early detection: A phased approach to implementation. Cancer, 126, 2379–2393. https://doi.org/10.1002/cncr.32887

Glenton, C. (2003). Chronic back pain sufferers—Striving for the sick role. Social Science & Medicine, 57(11), 2243–2252. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(03)00130-8

Global Lung Cancer Coalition. (2023). Symptom awareness, attitudes to lung cancer and views on screening 2023/24. https://www.lungcancercoalition.org/global-polls/symptom-awareness-attitudes-to-lung-cancer-and-views-on-screening-2023/

Grace, V. M., & MacBride-Stewart, S. (2007). ‘Women get this’: Gendered meanings of chronic pelvic pain. Health, 11(1), 47–67. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363459307070803

Hagège, S. (2020). Is menopause a social construct? Center for Scientific Research (CNRS) News. https://news.cnrs.fr/articles/is-menopause-a-social-construct

Hay, M. C. (2008). Reading sensations: Understanding the process of distinguishing ‘fine’ from ‘sick’. Transcultural Psychiatry, 45(2), 98–229. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363461508089765

Head, K. J., Bute, J. J., & Ridley-Merriweather, K. E. (2021). Everyday interpersonal communication about health and illness. In T. L. Thompson & N. G. Harrington (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of health communication (3rd ed., pp. 149–162). Routledge.

Jaworska, S., & Ryan, K. (2018). Gender and the language of pain in chronic and terminal illness: A corpus-based discourse analysis of patients’ narratives. Social Science & Medicine, 215, 107–114. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2018.09.002

Johansson, E. E., Hamberg, K., Westman, G., & Lindgren, G. (1999). The meanings of pain: an exploration of women’s descriptions of symptoms. Social Science & Medicine, 48(12), 1791–1802.

Keogh, E. (2021). The gender context of pain. Health Psychology Review, 15(3), 454–481. https://doi.org/10.1080/17437199.2020.1813602

King, S. (2012). Pink Ribbons, Inc: Breast cancer and the politics of philanthropy. University of Minnesota Press.

Kugelmann, R. (2000). Pain in the vernacular: Psychological and physical. Journal of Health Psychology, 5(3), 305–313. https://doi.org/10.1177/135910530000500302

Kugelmann, R. (2003). Pain as symptom, pain as sign. Health,7(1), 29–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363459303007001305

Kugelmann, R. (2017). Constructing pain: Historical, psychological and critical perspectives. Routledge.

Leventhal, H., Nerenz, D. R., & Steele, D. J. (1984). Illness representations and coping with health threats. In S. E. Taylor, J. E. Singer, & A. Baum (Eds.), Handbook of psychology and health, volume IV: Social psychological aspects of health (pp. 219–252). Routledge.

Lewis, G. N., Shaikh, N., Wang, G., Chaudhary, S., Bean, D. J., & Terry, G. (2023). Chinese and Indian interpretations of pain: A qualitative evidence synthesis to facilitate chronic pain management. Pain Practice, 23(6), 647–663. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1111/papr.13226

Lock, M. M. (1994). Encounters with aging: Mythologies of menopause in Japan and North America. University of California Press.

Lock, M. (1998). Anomalous ageing: Managing the postmenopausal body. Body & Society, 4(1), 35–61. https://doi.org/10.1177/1357034X98004001003

Lock, M., & Kaufert, P. (2001). Menopause, local biologies, and cultures of aging. American Journal of Human Biology, 13(4), 494–504. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajhb.1081

Lupton, D. (2012). Medicine as culture: Illness, disease and the body. SAGE Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446254530

Lyons, A. C. (2009). Masculinities, femininities, behaviour and health. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 3(4), 394-412. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2009.00192.x

Lyons, A. C., & Chamberlain, K. (2006). Health psychology: A critical introduction. Cambridge University Press.

Lyons, A. C., & Chamberlain, K. (2017). Critical health psychology. In B. Gough (Ed.), The Palgrave handbook of critical social psychology (pp. 533–355). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-51018-1_26

Marlow, L. A., Waller, J., & Wardle, J. (2015). Does lung cancer attract greater stigma than other cancer types? Lung Cancer, 88(1), 104–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lungcan.2015.01.024

McGowan, L., Luker, K., Creed, F., & Chew‐Graham, C. A. (2007). ‘How do you explain a pain that can’t be seen?’: The narratives of women with chronic pelvic pain and their disengagement with the diagnostic cycle. British Journal of Health Psychology, 12(2), 261–274. https://doi.org/10.1348/135910706X104076

McKinnel, J. (2022). Grim Reaper HIV ads ‘contributed’ to violence against LGBT community, inquiry told. ABC News. https://www.abc.net.au/news/2022-11-22/hiv-coverage-contributed-to-lgbt-violence-inquiry/101677280?utm_campaign=abc_news_web&utm_content=link&utm_medium=content_shared&utm_source=abc_news_web

Morunga, E., Bean, D. J., Tuahine, K., Hohepa, K., Lewis, G. N., Ripia, D., & Terry, G. (2024). Kaumātua (Elders) insights into Indigenous Māori approaches to understanding and managing pain: A qualitative Māori-centred study. First Nations Health and Wellbeing – The Lowitja Journal, 2, 100025. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fnhli.2024.100025

Murray, M. (1997). A narrative approach to health psychology: Background and potential. Journal of Health Psychology, 2, 9–21.

Murray, M. (1998, 4-6 June). Stories all the way down: The narrative construction of health and illness [Paper presentation]. Annual Congress, Canadian Psychological Association, Edmonton, AB, Canada.

Murray, M. (1999). The storied nature of health and illness. In K. Chamberlain & M. Murray (Eds.), Qualitative health psychology: Theories and methods (pp. 47–63). Sage.

Nettleton, S. (2006). ‘I just want permission to be ill’: Towards a sociology of medically unexplained symptoms. Social Science & Medicine, 62(5), 1167–1178. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.07.030

Nettleton, S. (2020). The sociology of health and illness. John Wiley & Sons.

Noone, J. H., & Stephens, C. (2008). Men, masculine identities, and health care utilisation. Sociology of Health & Illness, 30(5), 711–725. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9566.2008.01095.x

Olafsdottir, S. (2013). Social construction and health. In W. C. Cockerham (Ed.), Medical sociology on the move (pp. 41–59). Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-6193-3_3

Parsons, T. (1975). The sick role and the role of the physician reconsidered. The Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly. Health and Society, 53(3), 257–278. https://doi.org/10.2307/3349493

Perović, M., Jacobson, D., Glazer, E., Pukall, C., & Einstein, G. (2021). Are you in pain if you say you are not? Accounts of pain in Somali–Canadian women with female genital cutting. PAIN, 162(4), 1144–1152. https://doi.org/10.1097/j.pain.0000000000002121

Perz, J., & Ussher, J. M. (2008). “The horror of this living decay”: Women’s negotiation and resistance of medical discourses around menopause and midlife. Women’s Studies International Forum, 31(4), 293–299. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wsif.2008.05.003

Prakash, T. (2020). Everybody hurts: Understanding and visualizing pain in Ancient Egypt. In S. Hsu & J. L. Raduà (Eds.), The expression of emotions in Ancient Egypt and Mesopotamia (pp. 103–125). Brill.

Phillips, M. M., Cornell, C. E., Raczynski, J. M., & Gilliland, M. J. (1999). Symptom perception. In J. M. Raczynski & R. J. DiClemente (Eds.), Handbook of health promotion and disease prevention. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4615-4789-1_5

Plage, S., Gibson, A., Burge, M., & Wyld, D. (2018). Cancer on the margins: Experiences of living with neuroendocrine tumours. Health Sociology Review, 27(2), 153–167. https://doi.org/10.1080/14461242.2017.1387068

Radley, A. (1994). Making sense of illness: The social psychology of health and disease. SAGE Publications. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781446222287

Radley, A. (1997). What role does the body have in illness? In L. Yardley (Ed.), Material discourses of health and illness (pp. 50–67). Routledge.

Rice, K., Connoy, L., & Webster, F. (2024). Gendered worlds of pain: Women, marginalization, and chronic pain. The Journal of Pain, 25(11), 104626. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpain.2024.104626

Rosendal, M., Jarbøl, D. E., Pedersen, A. F., & Andersen, R. S. (2013). Multiple perspectives on symptom interpretation in primary care research. BMC Family Practice, 14(1), 167. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-14-167

Rosenfield, D., & Faircloth, C. (Eds.). (2006). Medicalized masculinities. Temple University Press.

Sadock, B. J., & Sadock, V. A. (2008). Kaplan & Sadock’s concise textbook of clinical psychiatry. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Seymour-Smith, S., Wetherell, M., & Phoenix, A. (2002). ‘My wife ordered me to come!’: A discursive analysis of doctors’ and nurses’ accounts of men’s use of general practitioners. Journal of Health Psychology, 7(3), 253–267. https://doi.org/10.1177/1359105302007003220

Scott, S., & Walter, F. (2010). Studying help-seeking for symptoms: The challenges of methods and models. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 4(8), 531–547. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2010.00287.x

Stainton-Rogers, W. (2012). Changing behaviour: Can critical psychology influence policy and practice? In C. Horrocks & S. Johnson (Eds.), Advances in health psychology: Critical approaches (pp. 44–58). Bloomsbury Publishing.

Thom, R. R. M., & Grimes, A. (2022). Land loss and the intergenerational transmission of wellbeing: The experience of iwi in Aotearoa New Zealand. Social Science & Medicine, 296, 114804. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2022.114804

Tran, K., Delicaet, K., Tang, T., Ashley, L. B., Morra, D., & Abrams, H. (2015). Perceptions of lung cancer and potential impacts on funding and patient care: A qualitative study. Journal of Cancer Education, 30, 62–67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13187-014-0677-z

Tsampiras, C. (2008). Not so ‘gay’ after all – Constructing (homo)sexuality in AIDS research in the South African Medical Journal, 1980–1990. South African Historical Journal, 60(3), 477–499. https://doi.org/10.1080/02582470802417532

Tsampiras, C. (2014). Two tales about illness, ideologies, and intimate identities: Sexuality politics and AIDS in South Africa, 1980–95. Medical History, 58(2), 230–256. https://doi.org/10.1017/mdh.2014.7

Upsdell, A., Fia’ali’i, J., Lewis, G. N., & Terry, G. (2024). Health and illness beliefs regarding pain and pain management of New Zealand resident Sāmoan community leaders: A qualitative interpretive study based on Pasifika paradigms. Health Promotion Journal of Australia, 35(3), 724–733. https://doi.org/10.1002/hpja.800

Ussher, J. M. (2006). Managing the monstrous feminine: Regulating the reproductive body. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203328422

Ussher, J. M. (2008). Reclaiming embodiment within critical psychology: A material‐discursive analysis of the menopausal body. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 2(5), 1781–1798. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1751-9004.2008.00151.x

Utz, R. L. (2011). Like mother, (not) like daughter: The social construction of menopause and aging. Journal of Aging Studies, 25(2), 143–154. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaging.2010.08.019

Watson, J. (2000). Male bodies: Health, culture, and identity. Open University Press.

Werner, A., Isaksen, L. W., & Malterud, K. (2004). ‘I am not the kind of woman who complains of everything’: Illness stories on self and shame in women with chronic pain. Social Science & Medicine, 59(5), 1035–1045. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2003.12.001

Wu, J., Gale, C. P., Hall, M., Dondo, T. B., Metcalfe, E., Oliver, G., Batin, P. D., Hemingway, H., Timmis, A., & West, R. M. (2018). Impact of initial hospital diagnosis on mortality for acute myocardial infarction: A national cohort study. European Heart Journal: Acute Cardiovascular Care, 7(2), 139–148. https://doi.org/10.1177/2048872616661693

Yamasaki, J., Geist-Martin, P., & Sharf, B. F. (2016). Storied health and illness: Communicating personal, cultural, and political complexities. Waveland Press.

Zbierajewski-Eischeid, S. J., & Loeb, S. J. (2009). Myocardial infarction in women: Promoting symptom recognition, early diagnosis, and risk assessment. Dimensions of Critical Care Nursing, 28(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.DCC.0000325090.93411.ce

- In the case examples throughout this book, we have used a range of culturally diverse names to reflect the global and multicultural context of health psychology. These names are not intended to signal specific cultural or ethnic backgrounds unless stated explicitly, and no cultural assumptions should be inferred from them. ↵

- The cultural practice involving the partial or complete removal of external female genitalia for non-medical reasons. ↵

- Quantitative sensory testing (QST) measures a person's sensitivity to stimuli such as pressure, temperature, or vibration. It does not directly measure pain as a subjective experience, but rather helps identify heightened sensitivity, which may correspond with chronic pain conditions. ↵

The process of understanding bodily changes as signs of illness; influenced by personal, social, and cultural factors.

An observable, measurable indication of a health condition, such as a rash or fever, recognised as objective evidence of disease.

Subjective, personal experiences of a bodily sensation that may indicate illness, such as pain or fatigue.

The idea that bodily experiences, including illness, are shaped by social, cultural, and historical contexts, making the body both a biological and social entity. Within phenological traditions, “embodiment” includes how a person’s interpretations of their world, including their thoughts and feelings, are produced through their body, so that all knowledge is embodied.

How a particular illness is received by others; how they respond to people with different conditions.

A temporary social position granted to people who are perceived as legitimately ill, allowing them exemption from normal responsibilities and granting them support.

The process by which others recognise or deny a person’s claim to be ill, influencing whether that person receives sympathy, care, or assistance.

The efforts individuals make to convince others that their symptoms are genuine and deserving of medical attention or social support.

The denial of a person’s claim to illness, undermining their right to be seen as sick and thus barring access to support or understanding.

The negative labelling and social devaluation of individuals because of their illness, often leading to exclusion and discrimination.

A condition whose legitimacy is questioned due to uncertain causes, diagnosis, or treatment, making it difficult for sufferers to gain recognition and support.