2.1 Perspectives on health and illness

Tracy Morison and Ally Gibson

Overview

Taking a critical perspective, as we do in this book, involves going beyond the surface appearance of an idea or phenomenon to determine why it is the way it is (Baum, 2015). For (critically oriented) health psychology, this means scrutinising health-related issues through a lens that questions underlying assumptions, power dynamics, and social structures. It also means questioning our very understanding of the notion of health, which we frequently take for granted, and which is the focus of this chapter. The questions that may spring to mind are: What is the point of recognising and unpacking different, changing understandings of health and illness? And, Why is taking this critical perspective necessary or valuable? This chapter tackles these questions.

Learning objectives

In this chapter, we cover the following learning objectives.

- Explain how social and cultural factors shape different understandings of health and illness.

- Recognise and describe the main concepts influencing Western views and approaches to health and illness.

- Compare and contrast the biomedical model with alternative approaches, emphasising the limitations and benefits of each.

- Reflect on the significance of recognising and unpacking various interpretations of health and illness for improving healthcare practices and policies.

Introduction

How we conceptualise health and illness has significant implications for how health is addressed—both in terms of individuals’ lived experiences and the practices of those who provide care. Different understandings of health and illness shape how people experience and respond to disease and how society organises the treatment and management of illness—if it chooses to do so at all. At an individual level, one’s interpretation of illness directly influences the experience of symptoms. For example, if I interpret a headache as a sign of serious illness, I may feel anxious or distressed. In contrast, if I attribute it to tiredness, I am likely to be less concerned. These interpretations, in turn, influence how I respond to the symptom. This reflects a reciprocal (two-way) relationship between meaning making and action.

The same dynamic operates at the societal level: collective definitions of health shape how health issues are understood and addressed. Health policy offers a clear example of this (Baum, 2015). When “obesity” is framed primarily as a result of individual failings—such as a lack of self-control or motivation—policies tend to emphasise behavioural change, such as encouraging improved diet and exercise. In contrast, when broader structural perspectives are adopted, policy responses may target systemic contributors like “food deserts”, “obesogenic” environments, and socioeconomic inequities.

Both the examples mentioned above show that different ways of understanding health and illness—at the individual and societal levels—have very real material consequences. This is the central theme of this chapter and of the broader discussion in Part Two.

Health and illness as socially constructed

Health, as a concept, carries considerable cultural and social meaning; it is central to cultures worldwide and encompasses important ideas, deeply held values, and ideals (Baum, 2015). Different ways of understanding originate “from particular histories that are linked to distinctive cultures and places” (Pickren, 2019, p. 2). Therefore, as Radley (1994, p. 20) argued:

We cannot assume that words like ‘ache’, ‘pain’ or ‘doctor’ – or even ‘health’ and ‘illness’ for that matter – refer to things that remain the same wherever and whenever they are applied. This is true of the experiences of the sick as well as of the practices of the physicians and nurses who attend to them.

A valuable lens for understanding the different meanings attached to health and considering the socio-historical nature of understandings of health and illness is that of social constructionism. Social constructionism was initially very influential in medical sociology (Barker, 2010; Conrad & Barker, 2010; Nettleton, 2020) and only later taken up in psychology and drawn on by critical health psychologists (Burr, 2015; Chamberlain, 2015; Lyons, 2011). The following video provides a helpful overview. (You may also want to take a look at Chapter 1.2 for a more general discussion of social constructionist epistemology and Chapter 1.3 on using this theory as a research lens.)

What do we mean when we say illness is socially constructed?

Social constructionism is a theoretical perspective that encompasses an array of theories that, as Burr (2015, p. 2) puts it, bear a “family resemblance” toward one another. This “family of approaches”, according to Burr (2015), commonly:

- takes a critical stance toward taken-for-granted knowledge (i.e., question what is assumed to be common knowledge/the way things are),

- treats all ways of understanding the world as historically and culturally specific (i.e., how people understand the world depends on the time and culture they live in),

- sees social interaction as sustaining different forms of knowledge/ways of understanding the world,

- shows how specific ways of understanding maintain some social actions, behaviour, or practices while limiting or preventing others, affecting how people are allowed to behave in society and how people from different social groups may be treated (e.g., given advantage or disadvantaged).

Claiming that something is socially constructed, therefore, is to draw attention to its taken-for-granted nature and the social practices it sustains (Barker, 2010). Accordingly, a social constructionist perspective of health holds that “what counts as health or sickness and which problems need health care are culturally and socially constituted” (Pickren, 2019, p. 2). Scholars taking this approach call attention to the inter-relationship between constructions of illness and how illness is expressed, perceived, understood, and responded to at the individual and societal levels (Barker, 2010).

Importantly, claiming that an illness is socially constructed is not to deny its biological basis. We are not suggesting that illness is imagined or denying people’s suffering or pain. Instead, taking a social constructionist perspective means seeing illness as having both a biological basis and a symbolic dimension. The social meanings ascribed to certain conditions—and health and illness more broadly—are shaped by biological and social factors (Barker, 2010; Olafsdottir, 2021). Indeed, social and cultural factors impact so many aspects of health and illness, including how we as individuals and societies comprehend biological anomalies, respond to disease, and interact with medical personnel, as well as how treating and caring for the sick are conducted (Olafsdottir, 2021).

Accordingly, those studying health and illness from a social constructionist perspective focus on how cultural and social systems shape the meanings and experiences of sickness or bodily impairment (Conrad & Barker, 2010). Researchers generally consider the following three focal areas, identified by Conrad and Barker (2010):

- The cultural meaning of illness: Illness carries cultural meanings (e.g., ab/normality, im/morality, danger) that affect how society treats people with those illnesses and how those illnesses are experienced.

- The subjective experience of illness: Illnesses are socially constructed in the sense that the experience of illness is shaped by how people understand and deal with it, drawing on various personal and social meanings.

- The social production of medical knowledge: Instead of being value-neutral, medical knowledge can reflect and perpetuate social inequality.

The idea that illness is socially constructed can initially be quite challenging. Most people take the physical experiences of illnesses for granted as real, with little awareness of how these are shaped by the ways their culture makes sense of illness. The understandings and responses that flow from them seem completely obvious and normal from within a particular time and place. “The last thing fish would notice is water” (Linton, 1936, in Conrad & Barker, 2010, p. S69), as the saying goes. Therefore, considering these experiences, understandings, and responses as embedded in specific worldviews and social and historical settings can feel somewhat jarring (Olafsdottir, 2021).

Sometimes, stepping out of one’s own frame of reference allows one to recognise what is often taken for granted as “just the way things are”. Doing so can involve examining how social meanings about health and illness are re/created in social interaction across place and time: turning either to other cultures or looking back in time at one’s own culture, as we do below.

What we mean by “culture”

We use the term culture to refer to the inherited set of implicit and explicit guidelines a society provides for understanding the world, responding to it emotionally, and behaving toward others. Cultures are systems of shared meanings—transmitted through language, symbols, rituals, art, and institutions—that shape what we value, how we act, and how we interpret health and illness.

As Helman (2007) explains, culture influences not only beliefs about the causes of illness and acceptable forms of care, but also who is seen as responsible for health, and what it means to live a “healthy” life. Durie (1985, 2001) emphasises that cultural identity influences how people define health goals, interpret illness, and engage with healthcare. In this view, culture is not a static background factor but a dynamic, living context through which health is made meaningful.

This broad, systemic understanding of culture helps us move beyond narrow definitions that equate culture only with ethnicity or nationality, referencing culture as a demographic label or variable. Instead, we approach culture as central to how people experience their bodies, define illness, seek care, and imagine healing.

Cultural variation: different understandings across place

People make sense of health through a variety of cultural meaning systems. These may include distinct models of disease, frameworks for understanding wellness and illness (such as magic or spiritualism), culturally specific conditions, traditional and Indigenous healing practices, and, more recently, Westernised forms of healthcare and their associated norms (Vaughn et al., 2009). These meaning systems serve as explanatory frameworks and draw on diverse sources, including social networks, media, biomedical knowledge, early childhood learning, folklore, and more (Vaughn et al., 2009; Ward, 2019). As Ward (2019, p. 19) observes, “there is no single, canonical body of facts about illness. There are knowledges.” These various forms of knowledge may complement or contradict one another, and differ across cultural contexts, reflecting the diverse ways that people around the world understand health, illness, and healing (Vaughn et al., 2009).

Research—including cross-cultural studies[1]—on health perceptions highlights how these understandings are subjective and shaped by a person’s socio-cultural location and the specific meaning systems available to them. Individuals draw on the dominant knowledge systems in their context—such as religion, science, or folklore—to interpret bodily sensations like pain or discomfort. These frameworks suggest likely causes (e.g., spirits, sin, germs, stress, laziness), and inform appropriate responses (e.g., exorcism, prayer, herbal remedies, antibiotics, rest). (See Chapter 2.2 for more on this.) In doing so, particular physical sensations may be granted significance—or not—affecting how illness is experienced (Barker, 2010), and in some cases, making certain conditions recognisable only within specific cultural settings (Shorter, 2008).

Findings from cross-cultural studies also reveal that some illnesses appear in certain societies but not others. These are known as culture-bound or culture-specific conditions (Barker, 2010; Baum, 2015). They are sometimes also referred to as psychosomatic conditions, given their combination of psychological and physical (somatic) symptoms. As King (2020, p. 295) explains, these conditions “are subject to a particular set of cultural beliefs and practices, rather than being a tangible medical ‘truth’ that is universally recognized, across all cultures.” The examples in Textbox 1 illustrate how culturally specific beliefs shape the experience and reporting of symptoms, producing conditions that are recognisable only within particular cultural frameworks.

Suudu: A culture-specific syndrome of painful urination and pelvic “heat” that is prevalent in women and men in South India, particularly in the Tamil culture. It is commonly ascribed to an increase in the body’s “inner heat”, often due to dehydration. Tamil cultural norms about health, body regulation, and environmental adaptation shape the concept of Suudu. The idea of managing body heat reflects the cultural importance placed on harmony within the body (Chhabara et al., 2008). Though the symptoms of painful urination and discomfort may overlap with conditions like urinary tract infections or dehydration, the local attribution to “inner heat” is unique to the cultural context of South India. In biomedicine, the idea of internal heat as a cause of illness is not typically recognised, marking this condition as culturally bound due to the localised understanding of its aetiology (cause) and treatment.

Pre-Menstrual Syndrome (PMS): “A highly ‘culture-bound’ phenomenon” (King, 2020, p. 295), pre-menstrual syndrome (PMS) is characterised by physical and emotional symptoms in Western women before menstruation, such as mood swings, irritability, and fatigue. Unlike women from other cultures, who report primarily physical changes (e.g., water retention), Western women experience significant psychological changes. PMS is linked to socio-cultural factors and Western gender norms, reinforcing the stereotype of women as “irrational” (King, 2020). The “myth of the irrational female”, which portrays women as pathologically emotional (King, 2020, p. 288), supports Western cultural constructions of the pre-menstrual phase as a time of psychological disturbance and debilitation. Research shows that societal perception of women and their bodies impacts symptom perception of pre-menstrual bodily changes (Chrisler, 2008; Johnson, 1987).

The example of culture-specific illnesses illustrates “the social constructionist claim that illness and disease are something beyond fixed physical realities; they are also phenomena shaped by social experiences, shared cultural traditions, and shifting frameworks of knowledge” (Barker, 2010, p. 148).

Historical variation: changing Western understandings of health and illness

It can be tempting to consider other cultures’ “strange” or “exotic” understandings of health as socially located while taking one’s own cultural framing for granted. From a social constructionist perspective, however, all conceptualisations of health and illness, including our own, are culturally based belief systems; this position necessitates seeing all cultural knowledge as relative (Pickren, 2019). As Barker (2010, p. 148) states:

From a social constructionist perspective, the task is not necessarily to determine which of the two societies has the correct ideas about illness or which illnesses found only in certain places or certain times are “real”. Instead, the task is to determine how and why particular ideas about illness appear, change, or persist for reasons that are at least partly independent of their empirical adequacy vis-à-vis biomedicine.

Thus, social constructionists reject questions about whether some conceptualisations of illness more accurately reflect reality than others (Barker, 2010). Therefore, the modern, medically dominated Western context in which health psychology is situated should not be taken for granted; it must also be considered a product of time and place, with strengths and limitations (Radley, 1994). This historical specificity is evident when considering shifts in Western understandings of what it means to be ill or well, as in the example of body ideals and health in Textbox 2.

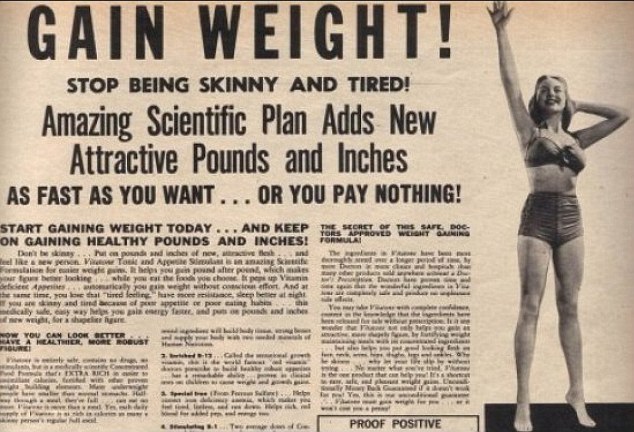

How people feel about their body shape and weight is a powerful example of how culture and historical differences affect how people think about health. This example highlights how cultural norms and values shape perceptions of physical health and influence diet, exercise, and body image behaviours.

How people think about body weight has continually changed throughout history in Western countries, influenced by religious, philosophical, and medical views (Sampson, 1996). Being thin has become increasingly seen as a sign of health, beauty, and success. In the 20th Century, this cultural ideal became more popular thanks to the growth of mass media, fashion trends, and medical discourse that stressed the dangers of obesity. Thinness may have been seen as a sign of being poor, sick, or not getting enough food, not as a sign of being successful or beautiful. Vintage advertisements for weight gain medications and exercise plans illustrate that at points in time in the West, weight gain was aspired to as earnestly as many aspire to weight loss today. The vintage advertisement below (Figure 2.1.3.) from the UK’s Daily Mail newspaper shows how skinniness was associated with poorer health and unattractiveness.

On the other hand, larger bodies were often seen as signs of wealth, fertility, and social status in many societies in the past. For example, in some cultures, particularly in parts of Africa and Polynesia, larger body sizes were traditionally associated with prosperity, fertility, and social status. This view persists in many societies beyond the West. For example, in Pasifika[2] cultures, larger bodies may signify strength, status, and familial wellbeing—meanings that are often stigmatised in Western public health discourse, yet are deeply embedded in community values (Warbrick, 2019;

In this snippet from her TEDTalk, medical anthropologist Nancy Chen reflects on how the cultural histories of body ideals have changed. As she discusses, a fuller figure may still be viewed as a symbol of beauty and health. Individuals in these spaces may face less pressure to conform to Western standards of thinness. On the other hand, Warbrick et al. (2019, p. 128) argue that “Indigenous peoples in Western countries commonly experience racism and fat shaming. Rather than improving health for indigenous peoples, weight and weight loss–centred approaches may actually cause harm. Initiatives based on indigenous knowledge are more relevant than those focussed on weight loss”.

The example above shows the changeability of understandings of health within place, as they are shaped by shifting frameworks of knowledge, shared cultural preoccupations, norms, and experiences. Likewise, some illnesses—like fugue, hysteria, and neurasthenia—that existed in late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century Western societies—have disappeared (Barker, 2010).

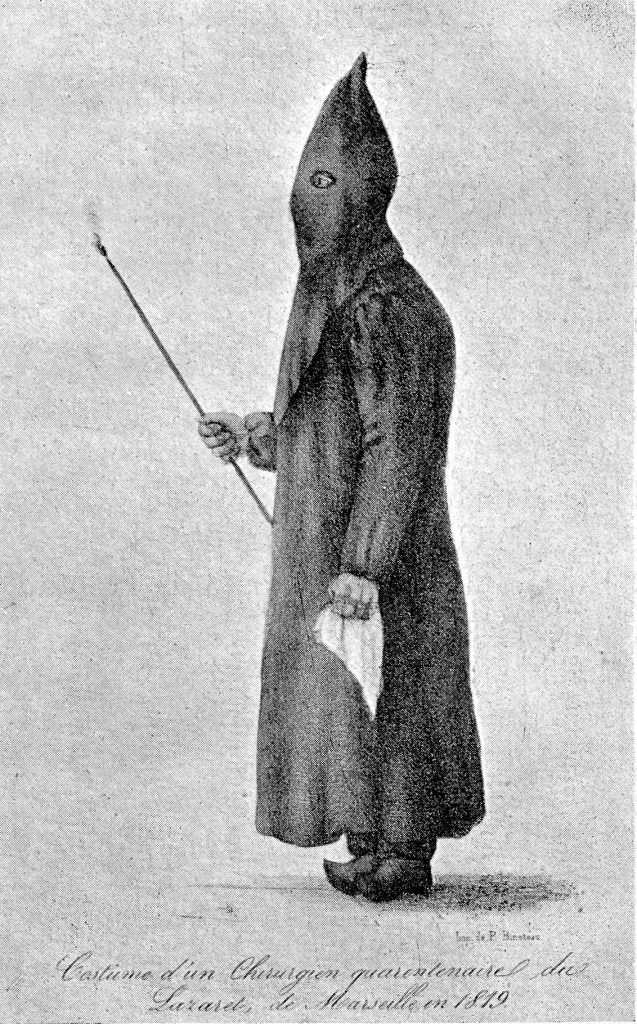

Changing understandings of health and illness are related to contextual changes, which have, in turn, shaped how sickness is treated (Radley, 1994). For example, in the West, before the emergence and dominance of the biomedical model, supernatural or religious explanations of ill health linked physiological functioning to a person’s emotional and spiritual life, which had several implications (Ferngren, 2012). Emphasis on spiritual causes meant that treatment often consisted of (Christian) religious practices, such as repentance, exorcism, or prayer, rather than physicians performing physical examinations. Pre-Christian beliefs conflated illness or suffering with people invoking the anger of gods, who thus brought on plagues, famine, or other misfortune. Such beliefs prompted and justified people being abandoned by others. While early Christian beliefs perpetuated the link between illness and sin, people who were unwell (physically or mentally) were viewed compassionately and as having an opportunity to restore health through spiritual practice (Ferngren, 2012). At the same time, due to the poor efficacy of medical treatment, medical care involved helping patients bear their ailments and was an (expensive) last resort. As the effectiveness of medical treatment improved, doctors focused increasingly on the body and not the psyche, to save the person rather than their soul.

As Western society gave way to secularisation in the nineteenth and twentieth Centuries—and a move away from the power of the church—medicine became a profession separate from religion, with spiritual practices erased from medical treatment. At the same time, health and illness became increasingly associated with employment and productivity, providing motivation to cure the sick so they could work. This linkage of health and productivity was strengthened by the rise in capitalism through these centuries as the prevailing socioeconomic system of Western society (Radley, 1994; Olafsdottir, 2013)—as discussed further below.

Given the successes and resultant status of Western medicine, founded upon the biomedical model, Olafsdottir (2013, p. 49) acknowledges:

It is possible to consider medical knowledge as neutral and simply reflecting reality. Along those lines, changes in how we think about health and illness, as well as treatment, reflect scientific processes, and if they change over time, it is because we know more now than we did in the past.

Without diminishing Western medicine’s gains, Olafsdottir (2013) problematises this assumption and its underlying progress narrative. She argues that, like all human knowledge, medical knowledge is produced in a specific socio-political setting, as explained below and throughout Part Two of this book. Research highlighting the social construction of medical knowledge illustrates how biomedical definitions of health and illness, like all knowledge systems, have components that may have less to do with scientific norms than with various cultural and political agendas (Conrad & Barker, 2006; Olafsdottir, 2013).

For example, a large body of research highlights how medical knowledge is shaped by the current gender norms of the era during which it is produced (Martin, 1991). Western patriarchal beliefs about femininity and women’s sexuality and “proper” place (i.e., submissive or subordinate) in society are shown to be embedded in medical knowledge regarding pregnancy, pre-menstrual syndrome (PMS), childbirth, and menopause. This knowledge can be used to limit women’s freedom in ways that seem factual and ideologically neutral; for instance, by claiming that women are too “hormonal” to hold leadership roles or are naturally more suited to domestic roles than economic ones (Ussher, 2008, 2022; Ussher & Perz, 2013). We unpack such arguments in more depth in Chapter 2.3, where we discuss diagnosis and medicalisation.

Taking a step back: looking critically at the biomedical model

The biomedical model is central to how people think about health and illness, particularly in Western/ised societies. As Crawford (2006, p. 403) points out, “the meaningful practice of health is inextricably linked to the science, practice and layered meanings of biomedicine.” Understandings of health, disease, and bodies are thus heavily influenced by the principles and practices of biomedicine, which has become the dominant framework through which we interpret the body, diagnose illnesses, and approach treatment. To fully grasp how health is viewed today, it is essential to understand the biomedical model and its close alignment with dominant Western values. To reiterate, the aim is not to assess the truth or accuracy of this model but to understand it as a knowledge system that, like all systems of knowledge, has strengths and limitations.

The biomedical model has undoubtedly contributed to significant advances in disease prevention and treatment, leading to the development of medications, vaccines, and surgical procedures (Lyons & Chamberlain, 2006; Rohleder, 2012). However, critics argue that these successes have sometimes been overstated, with less attention given to adverse outcomes or side effects (Olafsfdottir, 2013). These critiques also highlight that the most substantial improvements in population health can be attributed to earlier public health measures, such as better living conditions, poverty reduction, and improved hygiene and nutrition, rather than medical advances—though these certainly played a role later (Wilkinson & Marmot, 2003). We discuss these in more detail later in this chapter.

The contribution of these social and environmental factors to disease began to be recognised early in the 1800s. At that time, researchers began recognising the clear links between disease and poverty. For example, Friedrich Engels (a German philosopher) demonstrated how England’s poor living and working conditions contributed to ill health. Engels showed that diseases like “the black lung” in miners were linked to suboptimal working conditions and were, therefore, preventable. He also demonstrated that the overcrowded, squalid living conditions faced by the working class could explain the higher mortality rates among English labourers than professionals. Similarly, John Snow’s famous discovery of the Broad Street pump’s role in spreading cholera highlighted the social and environmental factors contributing to disease. These early efforts demonstrating the social dimensions of health laid the foundation for public health measures and “social medicine”, but were largely ignored by the biomedical model (Germov, 2009).

Instead, mainstream medicine followed a different path: that of biomedical science, neglecting social determinants in favour of biological explanations. The biomedical model is grounded in the same logic as physical sciences, prioritising empirical observation and measurable data. Hence, it emphasises biological processes and treats the body as an object of study. The focus on the observable body means that the biomedical model often neglects how the broader social context plays a role in health outcomes, largely disregarding social and environmental factors. This narrow focus, as we explain next, is the result of the time and place biomedicine originated: during what has become known as the Western Enlightenment era.

The biomedical model as a product of the Western Enlightenment

The Enlightenment, a period of intellectual and cultural transformation in the 17th and 18th centuries, profoundly reshaped Western thought by championing scientific reasoning, empirical observation, and individualism. During this time, thinkers emphasised the power of human reason to understand the world, favouring knowledge based on evidence that could be observed, measured, and tested. This shift towards scientific inquiry and rationality laid the foundation for modern medicine. Emerging from these Enlightenment ideals, the biomedical model privileges objective, measurable knowledge about health and illness, treating the body as a biological system whose diseases can be diagnosed, managed, and treated through scientific methods (Pickren, 2019). While instrumental in advancing medical science, this focus on observable physical phenomena often overlooks subjective experiences and social factors contributing to health, shaping how we understand and respond to illness today (Nettleton, 2020).

Scientific reasoning and the dominance of empiricism

The biomedical model adopted physical science’s empiricist epistemology, which is evident in its view that knowledge about health and illness should only come from observable, measurable, and testable evidence (e.g., physical signs, laboratory results, and clinical data) rather than subjective experiences or social factors (Pickren, 2019). Nettleton (2020) identifies five limitations of the biomedical model that stem from biomedicine’s grounding in the scientific model, namely,

- the body can be treated separately from the mind (mind-body dualism),

- disease is something to be treated in mechanistic ways,

- a preference for interventionist approaches to treating disease,

- explanations of disease are exclusively related to biology (biological determinism), and

- biomedicine, and its pharmaceutical or surgical treatments, is privileged as the most valid approach to health and illness, often dismissing or devaluing other cultural or traditional approaches and treatments (known as biomedical ethnocentrism).

These points echo the critiques of critical health psychologists (as discussed in Chapter 1.2). These assumptions, as discussed below, are linked to the particular social, historical, political, and cultural context of medicine developing within capitalist, neoliberal Western society.

Mind-body dualism is a philosophical concept initially proposed in the 1600s by French philosopher René Descartes, asserting the existence of two distinct entities: the mind and the body (Borcherding, 2021). This concept suggests that the mind and body function separately. The mind is considered the centre of consciousness, thought, and personal experience, while the body includes physical characteristics and functions. Although this idea has been thoroughly debated and challenged, it has historically influenced Western medical thinking, leading to the distinction between mental and physical health as separate areas, each needing a different approach to diagnosis, treatment, and care. In contrast with dualism, monism is the view that the mind and body are integrated as a single, unified substance or reality, not separate entities. In this way of thinking, mental and physical states are aspects of the same underlying reality, with consciousness and physical existence often framed as interconnected expressions of one unified system.

Psychological research in epigenetics and psychoneuroimmunology underscores the deep integration and inseparability of physical and mental states. For instance, chronic stress has been shown to alter immune function, increasing susceptibility to illness and illustrating the direct impact of mental states on physical health. These findings emphasise that mind and body operate as an interconnected system, where psychological experiences can manifest in physical changes, and biological states can, in turn, shape mental wellbeing. For example, historical trauma is shown to impact the health and wellbeing of Indigenous peoples in complex, harmful ways. Studies show that traumatic experiences can affect how genes are expressed. As these genetic modifications are passed to subsequent generations, they can experience increased vulnerability to bodily and mental conditions associated with trauma, stress, and adversity (e.g., Pihama et al., 2014; Reid et al., 2019; Schafte & Bruna, 2023).

The biomedical model is grounded in and reinforces mind-body dualism, separating psychological processes from the social realm. This separation supports a mechanistic view of the body, likening it to a machine with distinct yet interacting parts. In this model, health is understood as the efficient functioning of the body, and illness is seen as a breakdown that requires repair, removal, or replacement (Baum, 2015; Thompson, 2014). Treatments and techniques, like vaccinations, behaviour change programmes, medications, and surgeries, are continually developed to cure or alleviate symptoms in a highly interventionist “clockwork model of medicine” (Baum, 2015, p. 3).

As medicine and science became more intertwined in the 19th Century, the biomedical model of health emerged from natural sciences such as physiology, anatomy, and biochemistry (Nettleton, 2020). While some environmental and social factors are acknowledged, the focus is primarily on the individual body when explaining diseases (Nettleton, 2020; Radley, 1994; Rohleder, 2012). In this view, illness is caused by biological factors (e.g., organ or system dysfunction) or pathogens (i.e., germs, viruses) (Pickren, 2019). This approach is known as biological determinism, where biology is considered the primary determinant of health and illness. However, it has been criticised for its reductionism, as it narrowly focuses on biology and often neglects psychological and social influences on health (Nettleton, 2020).

Likewise, building on this biological reductionist view, biomedicine and pharmaceutical treatments or surgical interventions are seen as more valid and prioritised over other cultural perspectives, leading to “biomedical ethnocentrism” (Ferngren, 2012, p. 8). This belief (of the superiority of biomedicine) is based on the view of every disease as attributable to a particular physical entity (be it a virus, bacterium, toxin, parasite, and so on), and treatable by targeting and eliminating or controlling that entity through surgical and pharmaceutical interventions such as antibiotics, antivirals, or vaccines. As a result, other knowledge systems (e.g., Complementary and Alternative Medicine, Chinese Medicine) are often devalued (Ferngren, 2012).

Individualism and personal responsibility

The Enlightenment marked a significant shift in Western thought, emphasising the importance of individual rights, self-reliance, and personal responsibility. Western philosophers like John Locke championed the view that individuals are rational beings capable of making informed choices. This focus on individualism encouraged people to view themselves as agents in control of their own lives, shaping not only their destinies but also their health (Yadavendu, 2013). As a result, health began to be seen as a personal endeavour where individuals are responsible for their wellbeing, leading to the notion that a healthy life depends largely on one’s choices and actions.

This thinking gave rise to individualism, the philosophical and socio-cultural perspective that emphasises the individual’s autonomy, agency, and distinctive characteristics as the most critical factors shaping experiences and choices related to health. Individualism supports an overarching ethos in which health outcomes are primarily linked to human behaviours, choices, and biological predispositions, emphasising personal autonomy and responsibility for wellbeing. This viewpoint frequently emphasises the significance of self-care, self-regulation, and informed decision making as fundamental principles of health management (Baum, 2015).

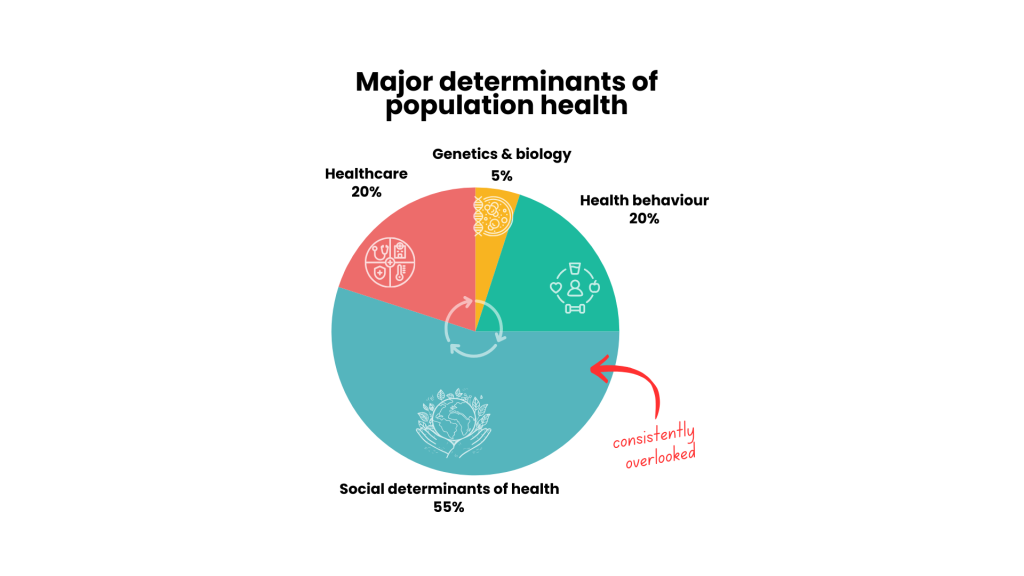

The biomedical model reinforces the concept of health as an individual issue by framing illness primarily as a result of personal behaviours and lifestyle choices. This perspective positions health management as largely dependent on individual responsibility, implying that people must take proactive steps—such as maintaining a healthy diet, exercising, and avoiding harmful habits—to prevent illness. Consequently, public health messaging often emphasises personal accountability over collective responsibility, which can lead to the marginalisation of social determinants of health, such as socioeconomic status and access to healthcare, ultimately overlooking the broader context in which health is experienced (Vera, 2020). Along with critical health psychologists, Indigenous scholars have extensively critiqued the emphasis on the individual human body, highlighting the pitfalls of overlooking the significance of socio-historical processes, such as colonisation, and cultural factors in understanding health (e.g., Dudgeon, 2020; Wilson et al., 2019). These factors account for a significant portion of health issues, as shown in Figure 2.1.5.

The rise of neoliberalism and its influence on health

Neoliberalism is an economic and political philosophy that grew out of and dovetails with the dominant Western ethos of individualism. This perspective prioritises market-driven solutions, advocating for minimal government intervention (e.g., social welfare, health promotion) and instead favouring individual responsibility and personal accountability. Importantly, under this framework, health transforms into a commodity that individuals are expected to manage as part of their personal goals. This shift positions health as something to be achieved through consumer choices, like fitness programmes, dietary supplements, and medications (Crawford, 2006). In this neoliberal perspective, the biomedical model’s interventionist approach aligns seamlessly with the belief that individuals should take charge of their health through various medical treatments and lifestyle decisions. This convergence reinforces the notion of self-management and also underscores individuals’ responsibility for their health outcomes, often neglecting the broader social and environmental factors that also play a crucial role (Petersen & Lupton, 1996).

With its strong emphasis on personal choice and responsibility, neoliberalism “is a significant driver of rising inequality” (Morison et al., 2019, p. 5). It has also been implicated in supporting and furthering European imperialism during the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries (Ratangee, 2023). The field of critical health psychology has been instrumental in explaining the intricate relationships between social disadvantage and health outcomes, drawing on decades of research in related health fields, like epidemiology and public health, that points to the fundamental role of the social environment in staying healthy or becoming unwell (Marmot et al., 1978; Marmot et al., 1991; Wilkinson & Marmot, 2003). This work shows that disease and mortality rates differ according to one’s social location, such as gender, sexual identity, ethnicity, race, and religion (See Part Three for more on this.)

A recent example of this is the COVID-19 pandemic, during which both prevalence rates and adherence to public health guidelines showed cultural variance. Individualistic countries exhibited higher rates of incidence and mortality and lower compliance rates with prevention measures compared to collectivist societies (Maaravi et al., 2021). Similarly, income inequality has been associated with rates of depression, identifying societies of higher income inequality as exhibiting higher population rates of depression (Patel et al., 2018).

Healthism: an offshoot of neoliberal ideology

The emphasis on individual responsibility has been reinforced and intensified by the rise of healthism, an offshoot of neoliberal ideology that gained dominance in the West during the later twentieth century. Chapter 1.4 provides a helpful background discussion of the ideology of healthism. Here, we focus on this relatively new Western way of understanding health and illness as part of the longer thread of Western thinking that privileges rationality and individual autonomy (free will). As such, healthism (and neoliberalism more broadly) go hand-in-glove with the biomedical model because, as we explain further below, it focuses on market-based solutions to health issues, promoting medical interventions and health products as solutions while minimising the role of broader social, economic, and environmental factors. Ultimately, this contributes to the dominant Western framing of health as a personal responsibility rather than a social issue, shifting the focus from social determinants of health to individual lifestyle choices (Bell, 2010; Brown & Baker, 2012).

“Healthism” refers to an ideology or worldview in which health is considered one of the most important pursuits in life. The term healthism was coined by Robert Crawford in 1980 to describe what he saw as a growing health consciousness in Western societies, which he described as “the preoccupation with personal health as a primary—often the primary—focus for the definition and achievement of well-being; a goal which is to be obtained primarily through the modification of lifestyles” (Crawford, 1980, p. 368). The central assumption of healthism is that health is completely within an individual’s control. Accordingly, health is considered a personal achievement, and individuals are expected to actively invest time, money and effort in their wellbeing through conscious lifestyle choices, regular medical checkups or interventions, and health products and services (Crawford, 1980; 2006).

The ideology of healthism, as a branch of neoliberal thinking, also supports the positioning of people as consumers of healthcare services and products (Bell, 2010). In this regard, Crawford (2006) highlighted the connection between healthism and consumer capitalism. A growing self-improvement or wellness mindset (which he called a “therapeutic ethos”) in Western societies encourages people to see health and self-care as critical aspects of their identity, making people more susceptible to consumerism as they pursue health-related products and services aligned with self-improvement. This mindset or “ethos” aligns with corporate interests as corporations profit from and reinforce the growing demand for wellness and health as a project of self-improvement. (Healthism’s origins in neoliberal economic thinking and its links to capitalism are explained in Chapter 1.4.)

Healthism, therefore, “situates the problem of health and disease at the level of the individual” (Crawford, 1980, p. 365) and fits well with the biomedical model of health. Even when wider environmental or social factors are acknowledged as contributing to health issues, it is still considered the individual’s responsibility to prevent or treat these problems (Crawford, 1980). To illustrate, Evans et al. (2018) give an example of the food traffic light system in the United Kingdom, which indicates the amount of salt, sugar, and fat in particular products. This system makes individual consumers responsible for monitoring their nutritional intake, but does little to regulate food producers’ practices, like advertising, portion sizing, and producing hyper-palatable foodstuffs.

Healthism creates a moral imperative of self-control and risk management (Crawford, 1980). A good illustration of this ideology in operation is the framing of cancer as an imminent “risk” to be avoided through constant self-surveillance and wise lifestyle choices in neoliberal Western societies (Bell, 2010; Gibson et al., 2015). While individual practices may well be beneficial, focusing solely on individual action can inadvertently position people as responsible for preventing cancer and to blame if they do become ill or fail to “beat” cancer. An individual-level focus can also make it difficult for people with cancer to express negative emotions, like a sense of helplessness or despair, as shown in work by critical health psychologists Gibson, Lee and Crabb (2015). Their research showed how healthism comes to bear on the illness narratives of Australian women with breast cancer. These women’s accounts of their illness experiences were shaped by the social expectation that they present themselves as taking responsibility for getting well through proactive self-monitoring (Gibson et al., 2015).

Healthist ideology, therefore, presents maintaining a healthy lifestyle as a moral duty both to oneself and society and, in this way, working to achieve health and wellness becomes an implicit marker of someone’s worth. Those considered to prioritise their health correctly are seen as disciplined, self-controlled, good citizens and, importantly, morally superior to those who are seen as neglecting their health (Brown & Baker, 2012). Those who fail to maintain healthy lifestyles are thus open to critique and sometimes even social stigma.

A classic example of this moral dimension of healthism is “fat shaming,” which is rooted in the assumption that people have complete control over their body size and health. Some of the views related to diet and exercise on which such stigma is based, and which readers may recognise, appear in Textbox 3. People are, therefore, held fully responsible for their weight gain and any associated medical issues. Those who fail to make healthy lifestyle choices are considered bad citizens and a burden on society (Spratt, 2023; Warbrick et al., 2019). Thus, healthism reduces (or over-simplifies) a complex issue into a matter of personal failure or success: “losing weight through diet and exercise [becomes] a simple matter of changing one’s behaviour when, for many, that behaviour is formed through a lack of choice, which is ultimately caused by conditions that are beyond their control” (Spratt, 2023, p. 89), such as biological, structural, and social factors. This narrow focus on personal responsibility not only reinforces stigma but can also obscure broader systemic factors that affect health inequities across different populations. In this regard, Indigenous people and people of colour are most often disadvantaged, and fat shaming is therefore said to have “a racist edge” (Warbrick et al., 2019, p 128).

- Framing exercise, fitness, and weight loss around ideas of self-discipline

- Describing oneself as “bad” for enjoying dessert or not exercising

- Making remarks about others’ body shapes, sizes, or weights

- Commenting on what others are eating or their habits

- Needing to “earn” a meal by exercising first

- Rewarding oneself by restricting food or burning a set number of calories

- Selecting foods solely according to calorie count, fat content, or carbohydrate levels and considering some meals a “cheat meal”

- Labelling foods “good” and “bad” based on how “un/healthy” they are

The possibility of social judgment or stigmatisation, as in the example of fat shaming, reinforces the perception of one’s value as intrinsically linked to one’s health status. Consequently, people often feel societal pressure to conform to health norms, leading them to pursue wellness regimens that can be dangerous and often feel like a requirement rather than a choice (Crawford, 1980).

The limits of the biomedical model

During the twentieth century, the limitations of this biological focus became increasingly apparent. Initially, this awareness arose from the “epidemiological transition” in Western societies, where increased food security and public health improvements shifted population patterns, including life expectancy and mortality. This transition replaced acute, infectious diseases (e.g., influenza, tuberculosis, measles, pneumonia) with chronic, degenerative diseases (e.g., heart disease, diabetes, cancer) as the leading causes of death (Wilkinson, 1994). Unlike acute illnesses, “chronic illnesses such as heart disease, cancer, stroke and diabetes are multiply determined disorders and psychological, behavioural and social factors play roles in their development” (Lyons & Chamberlain, 2006, p. 11). They are also strongly associated with routine daily behaviours (like diet, exercise, and smoking), and so are often called “lifestyle diseases” (Nettleton, 2020). The critical role of social factors in disease—as signalled by the broad shift from acute to chronic disease—is not accounted for by the biomedical model, leading scholars to question whether it alone is enough to address contemporary diseases (Wilkinson, 1994).

A significant overall limitation of biomedicine is that it has largely failed to consider the impact of illness on the lives of those affected (Baum, 2015), both in terms of their personal circumstances and cultural contexts. Since the biomedical model assumes that the human body is fundamentally a natural, objective, and neutral entity, the implication is that the body functions “normally” unless diseased, and that its functioning is experienced in essentially the same way by all people across cultures (Radley, 1994). These assumptions have been challenged by social science disciplines, like sociology and psychology, for neglecting the ways that psychological and social factors shape health at the individual level and beyond (Rohleder, 2012).

Another major critique of biomedicine is related to the power it is granted. This aspect was initially highlighted by Mishler’s (1988) investigation of the dynamics of doctor-patient consultations. His findings showed how “the voice of medicine” frequently dominated the conversations, allowing physicians to retain control. In contrast, “the voice of the lifeworld”, which reflects patients’ perspectives of their illnesses and lives, was routinely silenced, interrupted, and disregarded, leading people to feel misunderstood by healthcare providers. These findings are supported by much subsequent social scientific research, showing that the more powerful role of healthcare practitioners in healthcare interactions may lead to disregarding patients’ experiences and embodied knowledge, which do not fit neatly into medicalised frameworks and treatment plans. Healthcare providers’ objectives and desires also consequently dominate the concerns of patients (Berndt & Bell, 2021; more on this in Chapter 2.3 and Chapter 2.4).

Similarly, other researchers have looked beyond the interactional level to consider how medical power functions more widely. From a slightly more critical, Foucauldian perspective, this work emphasises how medical knowledge and disease entities do not simply reflect “given” biological realities that can be discovered, but involve judgements that draw on current values and ideals of society about what counts as illness and how it should be treated (Cooper & Thorogood, 2013). (Chapter 1.4 offers a thorough discussion of Foucauldian theory.) Medical definitions of health reflect the culture in which they are generated. For instance, in eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Europe, “hysteria” was commonly considered a physical ailment affecting women (Ussher, 2022). It became a common medical diagnosis for women who thwarted cultural ideals of women as submissive, even-tempered, and sexually inhibited, which functioned as a means of social control over “unruly” women (McVean, 2017; Ussher, 2022). Therefore, medical diagnoses can reinforce aspects of the status quo, serving those in power (Jutel, 2021; this is discussed further in Chapter 2.3).

To sum up, the biomedical model emerges not only from scientific advancements but is also deeply intertwined with the ideologies of individualism, neoliberalism, and healthism, which shape how health is understood and managed in Western societies. This model has proven effective in many instances, but its grounding in the physical sciences is better suited to understanding and treating purely physical phenomena. However, it is lacking when it comes to human issues, like health and illness, which are intricately interwoven with the social and cultural. Moreover, its strong emphasis on individual responsibility often overlooks crucial social factors contributing to health disparities. This narrow focus can limit the model’s effectiveness in addressing broader public health challenges, highlighting the need for a more integrated approach that considers individual choices and the wider social context. These limitations lead critical health psychologists to argue for a more holistic view to treat modern health conditions, as well as ensure that everyone can access what they need to be healthy, including those who are economically disadvantaged (Morison et al., 2019).

Beyond the biomedical model

We have argued thus far that the dominant Western biomedical model is a culturally based belief system, just like any other cultures’ conceptualisations of health and illness, but it has increasingly become globally dominant. It follows then that we must see health psychology in the same way: as deriving from a particular time and place and offering particular ways of understanding health and illness. These different understandings have since developed into different “strands” of health psychology as the discipline has matured (see Marks, 2002). In the interests of casting a critical gaze on our own discipline—as all good critical scholars ought to—in the final section of this chapter, we trace the rise of health psychology as part of growing efforts in the social sciences and beyond to develop more encompassing models for understanding health that consider its essential social and cultural dimensions.

The biopsychosocial model of health and the rise of health psychology

Health psychology was born from the growing realisation of the critical role of behavioural, psychological, and social factors in (especially chronic) diseases. The biomedical model of health has prevailed in the medical field for over two centuries, remaining largely unchallenged until more recently (Thompson, 2014). The questions levelled at the biomedical model prompted a widespread rethinking of the biomedical understanding of health as simply the absence of disease. There was a conscious shift in Western societies away from a purely reductionist, mechanistic understanding of health, and attempts to formulate a holistic understanding that includes the role of the psychological and social in people’s health (Schramme, 2013). This endeavour is most evident in the well-known definition of health in the World Health Organization’s (1948) constitution: “Health is a state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity”. This definition was intended to reflect the view that health is affected by various factors, including individual characteristics and behaviours, physical and social environments, income, and education levels (World Health Organization, 2017).

This questioning and critique does not underplay the value of modern medicine, nor does it suggest that we should do without it! Without a doubt, the biomedical model has significantly impacted disease prevention and treatment, producing a large amount of valuable knowledge that has supported the development of physical treatments for disease, like medications, vaccines, and surgical procedures (Rohleder, 2012). However, as mentioned previously, some critics claim that the successes of biomedicine have been over-emphasised over some of its adverse outcomes, harms, or side effects. They also point out that the most substantive gains in population health were related to the above-mentioned improvements in people’s living conditions—reducing poverty and supporting better hygiene and nutrition—and not medical advances (although these later played a role) (Olafsdottir, 2013.).

The growing dissatisfaction with the dominant Western biomedical model of health, especially through the 1970s, nevertheless led to the development of the biopsychosocial model, which provided an alternative approach to understanding health and illness and a basis for the new sub-discipline of health psychology. The model was developed within the medical specialisation of psychiatry by George Engel (1977) as an alternative to the biomedical model and the dominant approaches of behaviourism and psychodynamics within the field. Engel (1977) argued that the dualistic view of mind and body in medicine meant that for the psycho-social dimensions of mental illness to be given any meaning in psychiatry, they had to be first reduced to physiology or biochemistry. He, therefore, advocated for “a new model for medicine” (cited in Delfosse, 2015, p. 36): a more comprehensive approach rooted in general systems theory, which he believed would recognise a patient as a whole person—including their thoughts, feelings, and history (Gatchel et al., 2020).

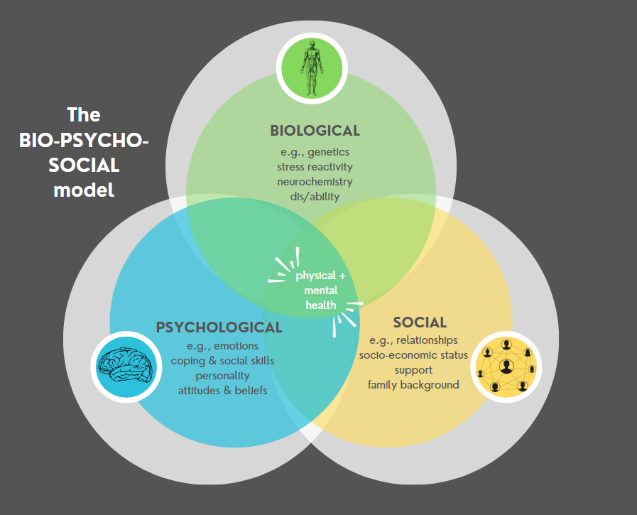

The biopsychosocial model holds that the complex interaction of biological, psychological, and social factors influences health and illness. The model deviates from the biomedical model in understanding that all three factors can affect the cause and progression of illnesses, not only biological ones (Miles, 2020). For instance, the development of a specific disease, such as cancer, can be influenced by various biological factors (e.g., genetic predisposition), behavioural factors (e.g., smoking and stress), and social conditions (e.g., social support and peer interactions).

While the idea that multiple factors contribute to a person’s particular form of ill health was not entirely new, what was novel about Engel’s model was its view of the dynamic interconnections between the three domains of biological, psychological, and social functioning. For example, psychological factors can impact biological functioning (e.g., changes in the autonomic nervous system and hormone production) and, in turn, be affected by biological processes (e.g., prompt cognitive impairment or influence mood).

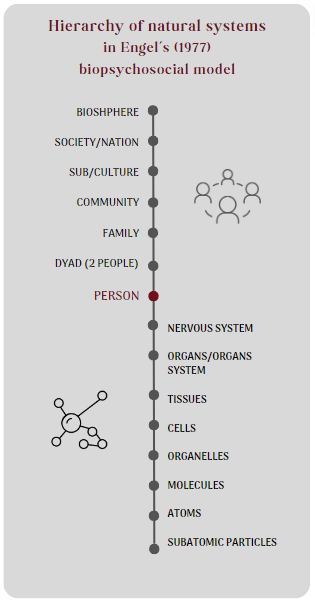

Drawing from general systems theory, rather than taking a linear causal understanding that is more suited to the natural or biological world, health issues are understood in terms of dynamic, multilevel, multi-system interactions. Put simply, the biopsychosocial model organises all levels of biological complexity along a continuum, from somatic to intrapsychic to interpersonal (see Figure 2.1.8). When arranged vertically, each of these levels is embedded in the ones above and contains the ones below, ranging from the molecule, cell, and organ system to the individual, dyad, family, community, culture, nation, and biosphere. While the biomedical approach holds that all phenomena are best understood at the lowest level of natural systems (e.g., cellular or molecular), a biopsychosocial perspective recognises that different medical situations can be scientifically understood at multiple levels along the natural systems continuum (Watson, 2012). In this sense, the model offers a holistic view of health.

The model encourages clinicians and researchers to look beyond the physical and to integrate knowledge from different domains for better understanding and treatment of health issues. Its strengths, therefore, lie in its holism and inclusiveness. The model’s fundamental premise has been validated by health psychology research highlighting the significance of psycho-social factors in illness (Miles, 2020).

At the same time as the biopsychosocial model emerged in the 1970s, growing recognition of the need for a broader understanding of health—beyond the biological—led to the involvement of several social science disciplines in issues of health and illness, including within psychology. Many psychologists who began focusing on issues related to medical care became aware of the larger environment’s role in people’s physical health and overall wellbeing. They began arguing that health and illness must be understood holistically and studied in terms of how the psychological and social worlds interact with the biological or physical (Morison et al., 2019; Rohleder, 2012).

At that time, health psychology emerged as a sub-discipline of psychology, explicitly using the biopsychosocial model of health and illness Engel had proposed. The biopsychosocial model became a widely accepted framework in mainstream health psychology. The model is strongly supported by those interested in individual physical and mental health (Rohleder, 2012).

Not social enough: the critical turn in health psychology

Over subsequent decades, into the 1990s, more and more critical scholars voiced the belief that the biopsychosocial model and other attempts to acknowledge the role of context in health and illness still fell short, giving rise to a “critical turn” in health psychology (Morison et al., 2019). While most health psychologists agree with the model’s basic premise, many offered criticisms, including those detailed in Textbox 4, below.

The biopsychosocial “model” is not a true model.

The biopsychosocial model does not hold the explanatory power of an actual integrated theoretical model (Crossley, 2000). According to Stam (2014), the model lacks theory and is vague. It therefore does not explain the relationship between the factors that are thought to influence one another and, therefore, cannot allow for investigation of a system’s different components and relationships (Rohleder, 2012). It has, therefore, been called simply a rhetorical device (Stam, 2014), a guiding framework (Suls & Rothman, 2004), or a way of thinking about health issues (Marks, 2002).

The biopsychosocial model privileges the biomedical; it remains essentially biomedical.

The model does not question the primacy given to the biological (Stam, 2014). Some scholars maintain that it “is still essentially biomedical and needs further theoretical work” (Lyons & Chamberlain, 2006, p. 12) to capture the social dimension in health psychology research.

The biopsychosocial model retains the biomedical model’s pitfalls.

Critics assert that because the model presents the mind, body, and society as largely separate, it retains biomedicine’s mechanistic view (Stam, 2014) and body-mind dualism (Crossley, 2000).

Critics argue that health psychologists often fail to apply the biopsychosocial model in a way that reflects its roots in systems theory. Instead of exploring how biological, psychological, and social factors interact dynamically, these elements are sometimes treated as a simple checklist of variables or referenced in overly simplistic, common-sense ways (Santiago-Defosse, 2014). (See also Chapter 1.2 for a critique of how the biopsychosocial model shapes understandings of the person in health psychology.)

It is perhaps unsurprising that much research using the biopsychosocial model has been shaped by the traditional scientific methods dominant in biomedical research—emphasising prediction and control over deeper understanding (Stam, 2014). This tendency can be better understood by considering the historical and cultural context in which health psychology emerged. As noted earlier in this chapter, perspectives on health are not developed in a vacuum—they are shaped by the socio-historical conditions of particular times and places.

Health psychology originated primarily in the United States and has been heavily influenced by its socio-political and intellectual climate (Pickren, 2019; Stam, 2014). In the 1970s, US American psychology was dominated by a neo-behaviourist paradigm, arising from efforts to establish psychology as a credible scientific discipline aligned with post–World War II ideals of progress and rationality (Parker, 2002). Within this framework, much health psychology research focused on individual “social cognitions”—that is, how people perceive, interpret, and make sense of health-related issues. These cognitive processes were seen as central to shaping behaviour, and by extension, health outcomes.

Working under the assumption that what was going on “inside people’s heads” is key to understanding health behaviour, researchers and practitioners used social cognitive theories to examine how individuals’ beliefs and attitudes, alongside social influences (e.g., peer pressure), impact health-related behaviours (e.g., smoking cessation, diet and exercise adherence, medication compliance, seeking medical care) (Horrocks & Johnson, 2014; Lyons & Chamberlain, 2017). This assumption underpins widely used models such as the Health Belief Model (Rosenstock, 1974) and the Theory of Planned Behaviour (Ajzen, 1985), which remain influential in health psychology today. (See Chapter 1.2 and Chapter 3.1 for more on social cognition models.) These models aimed to modify individual behaviours that were assumed to cause poor health. For example, Matarazzo (1982)— often credited with being one of the founders of health psychology—urged scholars to “aggressively investigate and deal effectively with the role of the individual’s behaviour and lifestyle in health and dysfunction” (p. 12). The development of the models was motivated by a wish to enable individuals to lead healthy lives and, importantly, to reduce healthcare costs for governments (Igarashi, 2015). This may help explain their enduring popularity in neoliberal contexts, where framing health as a matter of personal responsibility provides ideological support for reducing public investment in healthcare.

However, several health psychologists have argued that this individualised approach shares many of the same limitations as the biomedical model, reducing complex health issues to matters of behaviour modification and technical intervention (Igarashi, 2015). This critique was first raised by Stainton Rogers (1991), who argued that such models oversimplify human behaviour and obscure the broader socio-cultural context of health-related actions. These stripped-down explanations fail to meaningfully engage with the social, cultural, political, environmental, and historical conditions in which health behaviours are embedded (Horrocks & Johnson, 2014). As a result, they overlook the complexity, nuance, and at times, contradictions inherent in people’s everyday health practices (Mielewczyk & Willig, 2007; Murray & Poland, 2006).

Extending this argument, some critical scholars even questioned whether a health psychology that tries to be scientific can genuinely deal with the underlying causes of poor health, which are shaped by the larger social and cultural environments (Murray, 2012a; 2012b). Others argued that the emphasis on individual agency and responsibility in health psychology reinforces existing social hierarchies and sustains structural inequalities. These critiques highlight how individualistic models align closely with neoliberal ideals, which prioritise personal responsibility, self-management, and consumer choice as the foundation for health (Morison et al., 2019). Their concerns are backed by decades of evidence from epidemiology, public health, and medical sociology, including the Whitehall Studies (Marmot et al., 1978; 1991), The Black Report and Health Divide (Townsend et al., 1986), and the Acheson Report (Acheson, 1998).

In response to these critiques, there was a move towards extending the focus of health psychology beyond the individual, leading to the emergence of critical health psychology. One of the earliest and most comprehensive articulations of this field was offered by Stainton Rogers (1996), who envisioned critical health psychology not merely as a critique of biomedicine but as a broader reimagining of how psychology could engage with issues of power, inequality, and meaning in relation to health. Critical health psychologists introduced new ways of thinking and working—including the use of qualitative methodologies—to better capture the lived realities of health and illness (Chamberlain & Murray, 2017). By the early 2000s, critical health psychology had come to be recognised as a distinct approach.

While the early distinction between mainstream and critical health psychology was often described in terms of the quantitative/qualitative divide (e.g., Crossley, 2000), this is now seen as an oversimplification. Although qualitative methods remain central to critical work, what truly distinguishes critical health psychology is its openness to diverse ways of knowing and its commitment to advancing social justice (Morison et al., 2019). Reflecting this position, Wilkinson (2000) argued for theoretical and methodological eclecticism in critical health psychology research on the grounds that “all [methods] are useful, albeit for different kinds of research purposes, and in different applied contexts” (p. 360).

Despite methodological diversity, a unifying thread in critical health psychology is its commitment to understanding health in its full social complexity. This includes not only studying the impacts of structural inequalities and social determinants, but also challenging the systems and power relations that reproduce them. Critical health psychologists aim to contribute to real-world change through research, advocacy, and policy—efforts guided by a shared ethic of social justice (Morison et al., 2019). The International Society for Critical Health Psychology (ISCHP) summarises some of the core principles of critical health psychology, as shown in Textbox 5, which are further explored in Part Three of this book.

Critical Health Psychology’s common aims and interests:

- awareness of the social, political, and cultural dimensions of health and illness (e.g., poverty, racism, and sexism)

- dissatisfaction with traditional psychology’s positivist assumptions and lack of engagement with broader social and political issues

- application of critical theories (e.g., social constructionism, post-modernism, feminism, Marxism)

- use of qualitative and participatory research methods (e.g., discourse analysis, narrative inquiry, action research, and ethnography)

- active commitment to reducing human suffering and improving the conditions of life, especially for socially marginalised people.

Closing reflection

It is worth noting that in this chapter, we have examined how Western ideas about health and illness emerged and shaped modern health psychology, including the mainstream adoption of the biopsychosocial model as a more holistic alternative to biomedicine. We focused on Western perspectives because of their global influence, but it is vital to recognise that they are not the only ways of understanding health. Critical health psychologists have increasingly paid attention to Indigenous health models and methodologies that offer epistemological alternatives that foreground sovereignty, relationality, and lived experience (Durie, 2009; Haitana et al., 2020). For example:

- Te Whare Tapa Whā (Māori, Aotearoa New Zealand): A holistic health model that views wellbeing as a four-sided house, each wall representing a key dimension of health—taha tinana (physical), taha wairua (spiritual), taha whānau (family/community), and taha hinengaro (mental/emotional) (Durie, 1985).

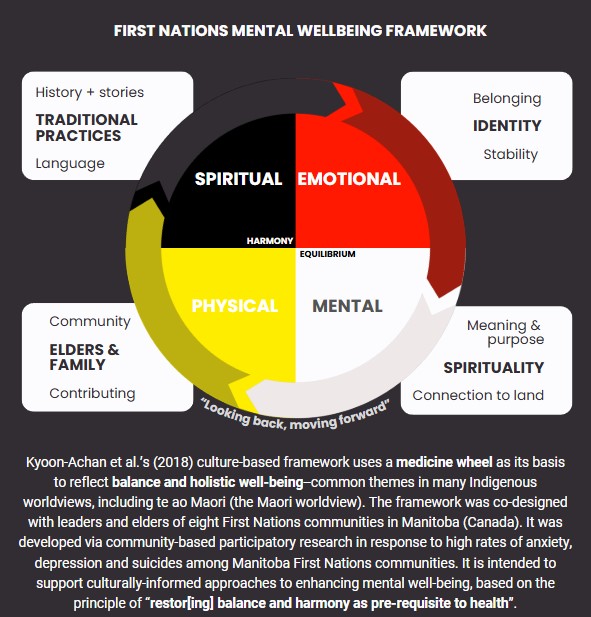

- Medicine Wheel (Various First Nations, North America): A framework emphasising balance and interconnection among four aspects of life—physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual—often represented by the four directions (Kyoon-Achan et al., 2021).

- Social and Emotional Wellbeing Framework (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Peoples, Australia): A model recognising the importance of cultural identity, community, family connections, land, spirituality, and ancestry in shaping health and wellbeing (Dudgeon, 2020; Dudgeon, Gibson & Bray, 2021).

- First Nations Holistic Policy and Planning Model (Canada): An approach that integrates traditional knowledge, community priorities, respect for Elders, spiritual values, and the interconnectedness of individuals, families, communities, and the environment (Reading, 2007; Reading, Kmetic, & Gideon, 2007).

Acknowledging these frameworks encourages a more inclusive and contextually grounded understanding of health and wellbeing. This has been shown to benefit Indigenous people (Haitana et al., 2020; Masters-Aawere et al., 2020), as, for example, in the First Nations Mental Wellness Framework (Kyoon-Achan et al., 2018) pictured below in Figure 2.1.9. Holistic understandings can also benefit the general population more broadly (Durie, 2009). Chapter 1.1 of this book discusses this issue in more depth, focusing on Māori understandings and health models.

Conclusion

Critical health psychology is essentially about “new ways of seeing” with the fundamental aim of making a difference in people’s lives. In this chapter, we have explored how different understandings of health and illness are profoundly shaped by socio-cultural factors, and how these perspectives have evolved. We have critically examined the dominant biomedical model, highlighting its limitations while acknowledging its contributions. By contrasting this with alternative frameworks that incorporate social, cultural, and psychological dimensions, we see that there is no single, universal way to understand health. Instead, health is a complex construct influenced by various factors, and taking a critical perspective helps to unpack these layers. Understanding and engaging with diverse views on health is essential for improving individual care and shaping more inclusive and effective healthcare policies. This holistic view opens new possibilities for addressing health and illness in a way that better serves individuals and broader society.

Summary of main points

Some key takeaway points from this chapter:

- Health and illness are not fixed or universal ideas; they depend on social, cultural, and historical contexts.

- Everyday understanding of health often reflect the dominant Western biomedical model, which treats health as mainly biological and overlooks social factors.

- The biomedical model comes from Western Enlightenment thinking, focusing on the body as a machine and encouraging individual responsibility for health.

- This view supports “healthism,” a Western ideology that treats good health as a moral duty and often blames individuals for their own poor health.

- Critics have argued that focusing only on biology and personal choices ignores how social conditions and inequalities shape health.

- In response to critiques, the biopsychosocial model was developed to integrate biological, psychological, and social factors, but it often still prioritises biomedical approaches.

- Critical health psychology goes further, examining power, inequality, and cultural differences that influence how people define and respond to illness.

- This social perspective shows that health beliefs and practices vary across cultures and change over time, challenging the idea that modern Western understandings are the only “truth.”

- Understanding health as profoundly social, and socially constructed, encourages looking beyond individual behaviours to address broader issues like poverty, discrimination, and social policies.

- Adopting a critical lens can lead to more equitable, culturally sensitive healthcare and public health strategies that consider the whole person and their material and social environment.

Further learning

Further reading

- Burr, V. (2025). Social constructionism. (4th ed.) Routledge. – A highly accessible book and a must-read if you want to understand more about social constructionism

- Chamberlain, K., & Lyons, A. C. (Eds.). (2022). Routledge international handbook of critical issues in health and illness. Routledge. – An excellent overview of contemporary health issues

- Pickren, W. (2019). Psychology and health: Culture, place, history. Routledge. – This book “traces the development of the relationship of health and psychology through a critical history that incorporates context, culture, and place”

More on body-mind interconnection and the social location of health

- Listen to this podcast by fx Medicine on The emerging importance of psychoneuroimmunology (PNI)

- Watch this TEDTalk by David Williams on “toxic stress”

- Read more on epigenetics and historical trauma in this blog post: Apter, T. (2020). The insidious legacies of trauma: Trauma is passed on from parent to child, but by what mechanism? Psychology today. https://www.psychologytoday.com/us/blog/domestic-intelligence/202005/the-insidious-legacies-of-trauma

- Read the classic article by Taylor, Repetti, & Seeman called Health psychology: What is an unhealthy environment and how does it get under the skin? [PDF]

Web resources

- The International Society for Critical Health Psychology‘s website has links to some great resources, as well as their podcast and wonderful blog featuring posts on various health-related topics written by health psychology academics and students.

Reflection and discussion

- The media play a significant role in shaping public understanding of health issues. What are some examples of an illness or health issue that has been the focus of media attention.

- How was the issue framed and what might the effects have been of framing it this way (i.e., treatment of sufferers, approaches to treatment, effect on general public)?

- Can you identify some of the dominant Western perspectives that shape these representations (e.g., healthism, individualism, body-mind dualism)?

- The diagnosis of hysteria is a good example of how understandings of what count as illness have changed over time. Reflecting on this “illness”, consider the following questions:

- Why do you think hysteria was predominantly associated with women?

- What social and cultural factors contributed to the rise of hysteria as an illness?

- What might this suggest about medical knowledge?

- Healthism is a dominant ideology shaping understandings of health.

- How does this ideology show up in your own life or in society around you?

- How does healthism and its “moral hierarchy of health” affect how people judge themselves and others?

- What are some ways to shift from this ideology toward a more holistic view of health?

- Many Indigenous understandings of health offer an alternative view to the narrower views of health that dominate in the West.

- Choose an Indigenous health model mentioned in this chapter to research and contrast and compare it to the biomedical model.

References

Acheson, D. (1998). Independent inquiry into inequalities in health: Report. HMSO (Her Majesty’s Stationery Office). https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/265503/ih.pdf [PDF]

Ajzen, I. (1985). From intentions to actions: A theory of planned behavior. In J. Kuhl & J. Beckmann (Eds.), Action control: From cognition to behavior (pp. 11–39). Springer-Verlag.

Barker, K. K. (2010). The social construction of illness: Medicalization and contested illness. In C. E. Bird, P. Conrad, A. M. Freemont, & S. Timmermans (Eds.), Handbook of medical sociology (6th ed., pp. 147–162). Vanderbilt University Press.

Baum, F. (2015). The new public health. OUPANZ

Berndt, V. K., & Bell, A. V. (2021). “This is what the truth is”: Provider-patient interactions serving as barriers to contraception. Health, 25(5), 613–629. https://doi.org/10.1177/1363459320969775

Bell, K. (2010). Biomarkers, the molecular gaze and the transformation of cancer survivorship. Biosocieties, 8(2), 124–143. https://doi.org/10.1057/biosoc.2013.6

Brown, B. J., & Baker, S. (2012). Responsible citizens: Individuals, health, and policy under neoliberalism. Anthem Press.

Borcherding, J. (2021). Mind-body problems. In D. Jalobeanu & C. T. Wolfe (Eds.), Encyclopedia of early modern philosophy and the sciences. Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-20791-9_583-1

Burr, V. (2015). Social constructionism. Routledge.

Chhabra, V., Bhatia, M., & Gupta, R. (2008). Cultural bound syndromes in India. Delhi Psychiatry Journal, 11(1), 15–18.

Chamberlain, K. (2015). Epistemology and qualitative research. In P. Rohleder & A. C. Lyons (Eds.), Qualitative research in clinical and health psychology (pp. 9–28). Palgrave Macmillan.