Witches, memes, and Spider-Man – traversing the participatory culture landscape

A participatory culture is one in which content spreads. As we saw in the previous section, this spread of content is facilitated by digital networks and by a propensity for peer-to-peer sharing.

Perhaps the perfect object of participatory culture is the meme. There are certainly low barriers to entry when it comes to making a meme, the production of which often relies on popular culture knowledge and communication skill rather than technological prowess: the key to a meme’s effectiveness is often the timing of its use, much like a well-timed one-liner in a conversation. Internet memes typically take the form of an image with a short caption, and design tools like Canva provide meme generators that require little more than a drag-and-drop action. The results can be impactful. Often humorous, Internet memes are not necessarily trivial – they can be used as discursive devices in public conversations about serious global issues (climate change, racial justice, gender equality, political reform) and they can also express deep and complex personal emotions (nostalgia, jealousy, empowerment).

What is a meme?

A “meme” is a unit of cultural information, and the term predates digital culture, coined as it was by biologist Richard Dawkins in 1976. Dawkins was interested in the way cultural information spreads from person to person, self-replicating in a similar manner to genes. Reinsborough and Canning remind us that a “meme” is really “any unit of culture that has spread beyond its creator—buzz words, catchy melodies, fashion trends, ideas, rituals, images, and the like” (2010: 34).

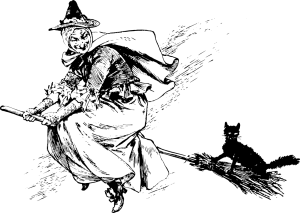

For an example of a centuries-old meme, take this image:

Image by StarGladeVintage from Pixabay

You likely recognise this person as a witch. Our minds very quickly break this image down into recognisable “signs” (see Chapter 4) – the pointed hat; the flying broomstick; the black cat; the age of the woman; her pointed nose, long skirt, and boots. Our cultural training helps us read this combination of signs. We’ve probably encountered similar images in childhood storybooks and in a plethora of popular media, where the signs are reproduced to the point of deep familiarity.

Why is this a meme? Because it can be described as a cultural idea, a unit of meaning, that spread until it was accepted as “true”.

The semiotic patterns that define “a witch” were derived from Christian discourse and established in the 14th and 15th centuries, when large numbers of people, mostly women, were persecuted by religious and political elites. These representational patterns were thus deeply entrenched in a politics of control by (male) authority figures over female embodiment and identity – and they were dispersed through printed media, aided by a new technology: the printing press. With the affordances of this new medium, pamphlets and broadsides were printed and distributed to the public, allowing information to be widely shared like never before. Often, these printed texts were image-heavy (since a large portion of their readership was illiterate) and relied for their storytelling power upon woodcuts: designs cut into blocks of wood, used to form illustrations in printed books. And so the iconography of the “wicked witch” was established.

This original witch meme circulated widely, but everyday folk (including, and especially, the women who it depicted) had no access to the means of cultural production through which such ideas gained power and prominence. Today, it’s a different story. Online we can create our own memes about witches using bits and pieces of culture, featuring characters from The Wizard of Oz, Harry Potter, or Minecraft, expressing an endless range of ideas about work, relationships, politics, and global events. Members of modern witchcraft communities and/or people who identify as witches can remake the signs of culture (including these long-ago ideas about pointy-hatted women on broomsticks) to express aspects of their relationship with a belief system. And yes, the meme of “wicked witch” can still be deployed in a harmful way, often to express misogynistic ideas (see Chapter 1 and the section on Julia Gillard’s misogyny speech for an example of this).

Memes are, of course, storytelling devices too. As Reinsborough and Canning point out, a meme is “a capsule for a story to spread” (2010: 34). Using the example of social movements, they explain that such movements contain common stories through which people can “express their shared values and act with a common vision”. These stories, they continue, are “encapsulated into memes—slogans, symbols, and rituals— that can spread throughout culture” (2010: 34).

For example, the iconic raised fist is a signifier of the Black Lives Matter movement but can also be described as a meme that encapsulates the stories the movement wants to tell about justice and the reclaiming of power. Like an Internet meme, the raised fist is identifiable, easy to replicate and share, and impactful because of the meanings it carries. Meanwhile, the movement’s website makes available a variety of tools to support and enable participation in the sharing of its messages, including social media templates and toolkits for activists.

Image by Ivan Radic, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Disrupting the top-down process of communication

What we’re starting to see here is that practices of meaning-sharing and meaning-making can be more or less open to participation; they can be top-down practices controlled by elite social actors, or they can be grassroots practices led by audiences and citizens. Indeed, they can be a fabulous, messy mix of the two, because we can use the products of popular culture as raw material (Fiske 1990) when sending our own messages and telling our own stories.

Such was the case for Preston Mutanga, a 14 year old Canadian fan of LEGO and animation who had for years been creating his own animated LEGO videos and posting them to his YouTube channel. In 2023, Mutanga caught the attention of Hollywood producers Chris Miller and Phil Lord when he created a LEGO version of the trailer for the movie Spider-Man: Across the Spiderverse. Mutanga was a self-taught animator who used the tools at his disposal: the free, open-source software Blender and the audience of followers he had cultivated on YouTube. His video impressed Miller and Lord, Across the Spiderverse’s producers, and Mutanga was subsequently invited to create a sequence that appeared in this commercially successful Hollywood production.

Is this an example of participatory culture at work?

Arguably, it is. The film industry has traditionally had very high barriers to entry – one must train for years and slowly work their way through the industry ranks before having access to the equipment, funding, and production and distribution networks required for making a film. However, there are lower barriers to artistic expression on YouTube, which since its inception in 2005 has allowed amateur and professional filmmakers alike to bypass industry gatekeepers and distribute their own video content. A culture that supports amateur creative endeavours and the sharing of user-generated content is also instrumental here, allowing Mutanga’s work to be widely seen, shared, commented on, and probably remade by others.

But let’s not forget that Across the Spiderverse is a tentpole production of the film industry owned by Sony Pictures and ultimately by the multinational media conglomerate Sony Corporation. Some would argue that Mutanga’s “participation” in the making of Spiderverse was less an authentic, spontaneous, equal-footed collaboration between professional and amateur animators and more a carefully crafted promotional move that capitalised on fan labour. After all, the story of Mutanga – a 14 year old genius working on his videos at night after school, shooting to fame on a global level as a result of his own dedication, hard work, and innovative thinking – fits very well with the Spider-Man narrative and brand. Interestingly, this example also reminds me of the way Henry Jenkins himself uses the Peter Parker character (aka Spider Man) as an embodiment of the youthful, innovative, and DIY spirit at the heart of participatory culture (see the video below).

TEDxNYED | Henry Jenkins

A participatory culture, then, is defined by a range of opportunities (or openings) through which citizens can get involved in representational practices, where access to influential meaning-making is no longer restricted to elite social actors. But this does not mean that all communicators are equal, or that the products of participatory culture (including the virtual and digital spaces of participation) are not owned, controlled, and monetised by a handful of media companies and powerful individuals.

Ahead in Chapter 8…