Participatory culture

This book has been grounded in the idea of communication as the sharing of meaning. The communication concepts we’ve explored in the previous chapters allow us to understand the mechanisms and practices through which meaning is shared, and the impacts and consequences of meaning-making on our identities, our cultures, our ideologies, our world.

But what powers do we as citizens have to get involved in this sharing process? To what extent can we shape the flow of meaning? And what tools and competencies enable us to participate in the production of knowledge and culture?

We’re going to finish this book by exploring the ways in which communication has shaped – and been shaped by – the rise of participatory culture.

Communication has always been participatory, to a certain extent. Interpersonal conversations tend to involve participants, not “senders” and “receivers”. Even in a broadcast model of communication, audiences participate in the production of meaning because they interpret and actively use messages, rather than simply receiving them.

But today it’s acknowledged that we live in a “participatory culture” where audiences and citizens have more access to cultural production processes than ever before. Mediated communication has become a lot more like a conversation, even as many of our conversations have become mediatised. And indeed, some of the most important conversations swirling through the public sphere today are led by citizens and grassroots movements rather than professional communicators or elite social actors.

An important way to think of participatory culture is to contrast it with consumer culture. In a participatory culture, we do more than consume the products of communication.

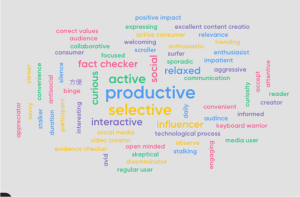

How many words can you use to describe the way you interact with communication and media content? Try to think of verbs: words that describe what you do as an audience, a receiver, or a media user. You will probably find you have a host of creative responses to this question. Maybe you binge, scroll, follow. You listen, watch, read. Maybe you also blog, share, remix, post, play, write, remake, lead. Your audience practices are not limited to consumption, and often, you will actively participate in the production and sharing of meaning.

Image: Word Cloud created by Master of Communication students describing themselves as “audiences”. Generated through Mentimeter. How many of these words indicate active participation?

What is “participatory culture”?

In a landmark report for the MacArthur Foundation, cultural theorist Henry Jenkins established a widely used definition of participatory culture that encompasses the following:

- Low barriers to artistic expression and civic engagement

- A strong support for creating and sharing one’s creations

- Mentorship, where what is known by the most experienced is passed along to novices

- A sense of social connection and a belief that our contributions matter.

(Jenkins et al. 2009: 3)

In combination, these elements of communication and culture in the 21st century allow citizens to be participants as well as spectators.

There are many ways of describing our communication landscape today: networked; mediatised; algorithmic. I like “participatory” because it places emphasis on the culture rather than the technology. Certainly, though, the development of participatory culture has been aided and facilitated by technological change. Today we have the opportunity to join online communities, create and share content, and shape the flow of media and communication in a way that we did not in decades past. As Jenkins and co-authors explain,

“Participatory culture is emerging as the culture absorbs and responds to the explosion of new media technologies that make it possible for average consumers to archive, annotate, appropriate, and recirculate media content in powerful new ways” (2009: 8).

For this reason, as technology changes and develops, the nature of our participation also changes – not because one drives the other, but because the two are intertwined.

For example, one of the findings of the 2023 Digital News Report – a global study of audiences’ engagement with news – was that open modes of participation, such as sharing and commenting on news stories, had declined in favour of participation on closed networks such as WhatsApp, Signal, Telegram, and Discord (Park et al. 2023: 16). In other words, news audiences seem to be gravitating towards means of participation that are more private, more trusted, and less toxic – and this shift is inextricably linked to the emergence of such newer, private or semi-private platforms.

But it’s important not to confuse participatory culture with participatory technology. Jenkins et al make an important distinction here between interactivity as a property of the technology and participation as a property of the culture (2009: 8).

Let’s consider social movement activism. For centuries, humans have been agitating in impactful ways, leading to social change. Today, digital tools facilitate activism, making it easier for messages to be shared and groups to be organised. Facebook, Instagram, Discord, and countless other social media services amplify voices and connect likeminded individuals. Augmented reality can literally enable activists to help others see the world in new ways. There are more opportunities for involvement in social movement activism than ever before, so much so that 2019 was dubbed by news outlets “the year of the protest” (see this article in the Washington Post).

But activism, even today, is not a solely technological practice. There are discursive and creative aspects to activism – from the colourful branding of movements like Extinction Rebellion to the careful crafting of messages by the young members of Fridays for Future. Many of the means by which activists express divergent ideas are decidedly analogue: sit-ins, walk-outs, takeovers, even “craftivism”. And running deeply through these varied creative offline and online practices is a culture that supports, enables, and embraces participation, in which members give their skills, time, and effort in return for a sense of belonging and agency that contributes to their identity.

So it is not technology alone that makes communication more participatory. Perhaps it’s more apt to say that the technological and digital tools with which we interact are part of the bedrock of participatory culture (but not its sole defining feature). And our interactions with digital technologies are a fascinating and ever-changing aspect of the way “participatory culture” as a communication concept is itself taking on new forms and new meaning. For example, in a 2018 article for the journal Transformative Works and Cultures, Nicolle Lamerichs predicts that with the mainstreaming of generative AI “we will share participatory culture with nonhuman entities” and “a new form of participation will emerge that involves nonhumans as important actors”.

This chapter will introduce you to participatory culture. We’ll explore the various, evolving forms of participation, and consider the relevance of this concept today. From memes and fan practices to misinformation and echo chambers, we’ll consider the challenges and opportunities associated with participatory culture and, fittingly, we’ll end with a reflection on the participatory aspects of open educational resources.

In this chapter…

Witches, memes, and Spider-Man – traversing the participatory culture landscape

Case study – Participatory culture, Doctor Who, and ‘My Doctor’ identity

Problems with participatory culture

Chapter 8 wrap-up and a conclusion of sorts

To continue reading Chapter 8, click “Next” in the bottom right corner or follow this link.