Collaboration and communication

In the previous chapter, we explored early models of communication. These models were developed by researchers who lived in very different worlds to us – different times and cultural contexts, informed by different concerns and priorities – but who shared with us a desire to know more about how communication works. We found that Claude Shannon’s transmission model still informs the way we think about communication today, but doesn’t fully capture the complexities of communication in a mediatised, digitised, networked world.

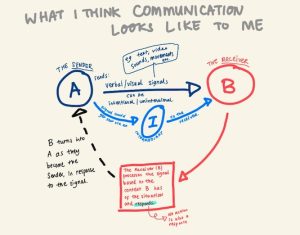

Often, I ask my students to create their own models of communication. (If you’re in my Communication Concepts class, you probably participated in this activity last week!). Usually, I ask students to do this in small groups, using whatever materials are at their disposal. I’ve had many fantastic, inventive responses to this prompt. Once, a group described communication using the image of a tree, which a talented group member sketched on a large piece of paper. These students wanted to show that communication can “grow” organically. Another student participating in a Zoom class grabbed a tangled ball of yarn (she was a knitter) and used it to show that communication is a complex process involving many strands. Yet another group proposed a “baguette model” of communication, using the analogy of baking bread – crafting a message, these students argued, is like making a dough and baking a baguette which you then share with your audience, and the message only takes on meaning when it is consumed (or, literally, eaten). These students wanted to show that even when communication happens very quickly, it still involves layers of processes rather than one singular transaction.

A model of communication, produced by Master of Communication students

What comes up time and time again in this activity is the idea of feedback. Invariably, at least one group in the class – usually several – creates a model of communication that is cyclical or circular, and they justify their decision by stating that communication involves feedback: when you have a conversation with someone, you might initially be the “sender” of a message, but your “receiver” will give you a response, and the sender/receiver roles continue to be exchanged in an often very rapid, intrinsic, and complex process. And if you’re engaging in mediated communication, feedback from your audience will similarly help you hone your message or make adjustments to your communication strategy.

When we acknowledge that communication involves feedback, we start to see that communication is a collaborative process. Even in a situation where the sender and receiver roles are upheld in a traditional way, the responsibility for meaning-making rests collaboratively between the two. As I write this chapter, I am encoding meaning into the text which you, the reader, are now decoding. Even though these two processes take place at separate points in time, their intersection involves a collaboration between you and I to create the meaning of this sentence, paragraph, and chapter. This somewhat beautiful dance between writer and reader is the only way by which this book could ever mean anything.

Image by Gerd Altmann from Pixabay. In an age of networked communication, meanings are collaboratively produced.

Collaboration, then, is an essential part of communication. It always has been. But communication practices are becoming increasingly collaborative, due to the digitisation of content and the growth of online networks.

By way of example, consider how social movements collaboratively produce meaning in rapid, powerful, and creative ways across digital and non-digital spaces. The meaning of the social movement #MeToo, for instance, was collaboratively built through a series of social media posts by women sharing their experiences of sexual abuse, supporting and confirming each other’s stories, and building public knowledge about crimes committed by powerful individuals within the media industries. Not only did the participants collaborate in the sharing of complex and powerful meanings about abuse, they created a shared space within which these stories could be told. And by “shared space”, I don’t mean a specific social media space. The movement unfolded across MySpace, Twitter (now “X”), and Facebook, as well as the real spaces of direct action and protest, but the space of #MeToo – a space within which it was right, necessary, and okay to share these stories – was collaboratively built by the communicators when they supported, endorsed, and extended each other’s messages, creating a collaborative truth that was impossible for the world to ignore.

This chapter will introduce the concept of collaboration. It will demonstrate that collaboration is an essential skill and attribute, particularly for communication practitioners but increasingly for all professionals in a rapidly changing world of work. It will unpack the features of successful collaboration and equip you with a language for explaining the importance of collaboration in the digital age.

In this chapter…

Collaborative knowledge-building

To continue reading Chapter 2, click “Next” in the bottom right corner or follow this link.