5. Why a clinic for teaching and learning about the climate crisis?

One of the key strengths of CLE is its potential to broaden and deepen[1] student learning in law by making the law real. Moreover, a clinical approach allows for learning climate-related law and practice unconstrained by disciplinary boundaries.

The ‘real’ aspect of clinic is critical in the case of teaching and learning about climate and the law. Whichever approach or model for a climate clinic is adopted, CLE involves engaging with the law in action, and through this encountering a justice system and laws that can operate fairly or unfairly, can help or hinder the client’s interests and which might be reformed (or transformed). Real clients and real matters rarely come packaged in the categories of a compulsory law subject. To provide effective and professional assistance in the ‘swampy lowlands’[2] of practice requires students to move beyond legal rules and doctrinal boundaries and to understand and take into account the web of legal and non-legal causes and consequences that make up any legal matter.

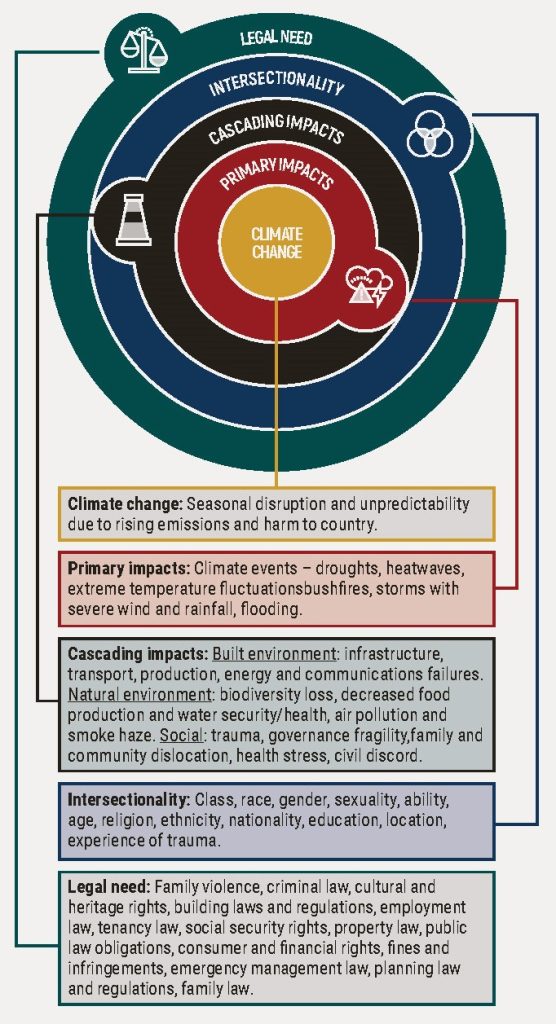

The focus in clinic on the problem or matter requires students to ‘[break] down existing knowledge boundaries’[3] as well as recognise the interconnections and interplay between law and other disciplines. This idea of connections is shown in the Federation of CLC’s climate justice wheel (see Figure 1). The climate crisis is inherently complex and multifaceted, with multiple stakeholders and points of entry; environmental problems are ‘polycentric and multidisciplinary’.[4] Sustainability scholars have criticised the focus of traditional legal education on fragmented categories and subcategories and the university’s regime of specialist disciplines and subdisciplines.[5]

While important in any area of legal practice, this broad perspective is perhaps crucial here. Skills in thinking across and beyond the traditional taxonomy of law, and integrating understandings from multiple disciplines, is needed to understand and — crucially — address the wicked nature of the climate crisis.[6] That is the case whether the work is transactional advice on setting up a new enterprise in the community energy economy, for which students need to understand the law and the complexity of energy markets;[7] or developing a guide for landowners to better understand their rights in a changed climate, which would be informed as much by the politics of the climate as by the law of property;[8] or advising a university on best-practice climate-mitigation measures, which would entail a cross-jurisdictional understanding of university governance.[9]

KEY QUESTION

- As a law student, how could you help the operation of a climate clinic? Consider your skills and experience, and not simply your legal knowledge.

- Adrian Evans et al, Australian Clinical Legal Education: Designing and Operating a Best Practice Clinical Program in an Australian Law School (ANU Press, 2017) 12. ↵

- Donald A Schön, The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action (Ashgate, 1991). See also discussion in Michele M Leering, ‘Integrated Reflective Practice: A Critical Imperative for Enhancing Legal Education and Professionalism’ (2017) 95(1) Canadian Bar Review 47. ↵

- Adrian Evans et al, Best Practices: Australian Clinical Legal Education (Final Report, 2013) 12. ↵

- Brian J Preston, ‘Benefits of Judicial Specialisation in Environmental Law: The Land and Environment Court of New South Wales as a Case Study’ (2012) 29(2) Pace Environmental Law Review 396, 396. ↵

- See discussion in Nicole Graham, ‘This is Not a Thing: Land, Sustainability and Legal Education’ (2014) 26(3) Journal of Environmental Law 395. ↵

- See Leering (n 2) 49; Julie Davidson and Anna Lyth, ‘Education for Climate Change Adaptation — Enhancing the Contemporary Relevance of Planning Education for a Range of Wicked Problems’ (2012) 7(2) Journal for Education in the Built Environment 63. ↵

- Eg, Melbourne Law School’s Sustainability Business Clinic. ↵

- Eg, Monash Climate Justice Clinic. ↵

- Eg, Bond Climate Clinic. ↵