5. Doing Law Differently: Climate Conscious Lawyering

Law cannot solve the climate crisis independently of other socio-economic and political institutions. However, lawyers can and must play an important part in broader collective and collaborative strategies to address climate change by developing and executing effective, equitable and rapid responses in the sphere of regulation. ‘Law and legal institutions constitute a critical component of a society’s adaptive capacity, and their influence may be positive or negative.’[1] Moreover, identifying ‘institutions that are resistant to change or that change in small increments’, including law, as ‘barriers to adaptation’, ‘especially when transformational shifts are required’, is critically important to addressing climate change. The converse is also true: institutions such as law can ‘facilitate the implementation of adaptation policies and respond quickly to new knowledge’.[2]

Key Question

- How can the institution of law shift from a negative influence on the adaptive capacity of society — a ‘barrier to adaptation’ — to a positive one?

The impact of climate change on law and regulation is apparent across all fields of law. The Law Council of Australia is the peak body for the legal profession in Australia and in 2021 issued its Climate Change Policy.[3] The policy highlights the various implications that climate change has for the legal profession and the shifting legal demands it creates through the changing needs of multiple sectors, industries and business entities to transition to a low-carbon economy. The policy observes that there are impacts to ‘agricultural, insurance and tourism sectors’, as well as changes in ‘employment … to support just transitions’. The policy also notes that the legal implications of climate change ‘are being tested before Australian, foreign and international courts and tribunals’.[4]

Novel (new) causes of action involving complex questions of law are arising across multiple legal practice areas, including administrative law, corporations law, tort, consumer law, contract law, insurance law, occupational health and safety laws, planning laws and water rights.[5] Particular industries and sectors require tailored legal advice to meet a myriad of climate change related challenges and opportunities. Diverse groups of Australians also present new demands, including rural, regional and remote communities and First Nations communities. The Law Council of Australia acknowledges that ‘the Australian legal profession has a critical part to play as it advises clients on the legal implications of all these shifts, challenges and opportunities [and] participates in the development of mitigation and adaptation measures’.[6]

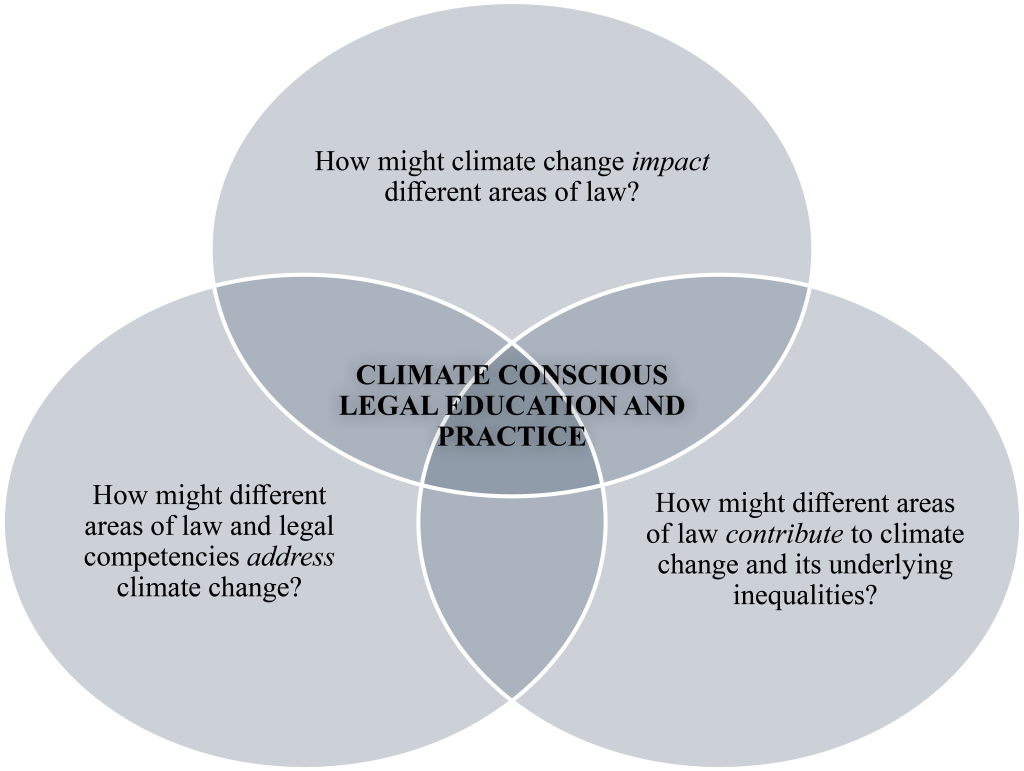

In light of the impacts of climate change on all areas of law and legal practice, ‘climate conscious lawyering’ is increasingly encouraged and championed as appropriate, if not necessary, to legal professional development and ethics.[7] As Justice Brian Preston — the Chief Judge of the Land and Environment Court in New South Wales — has explained, climate conscious lawyering requires an attentiveness to the relevance of climate change for different areas of law, and the provision of legal services, in a manner that seeks to meaningfully address climate change.[8] This edited collection adopts and expands upon Preston CJ of the NSW Land and Environment Court’s

conceptualisation of climate conscious lawyering by examining not only the significant role of law and legal practitioners in addressing the adverse impacts of climate change and promoting justice in a climate-transformed world but also critically engaging with the ways in which different areas of law may be implicated in authorising excessive GHG emissions leading to climate change and contributing to inequalities that underpin the climate crisis (see Figure 6).[9]

In agreement with other scholars calling for climate conscious lawyering, we support the development of several legal competencies necessary for ‘climate conscious legal education and practice’. These include essential competencies for lawyers more generally, such as ‘problem solving, legal analysis and reasoning, legal research, factual investigation, communication, counselling, negotiation, litigation and dispute resolution, procedures, organisation and management of legal work, and resolution of ethical dilemmas’.[10]

At the same time, due to the ‘legally disruptive’ nature of climate change,[11] this edited collection suggests that additional legal competencies will be necessary to respond to the climate crisis, including an understanding of the interaction between different areas of law in terms of the applicability to climate change; an appreciation of multi-level approaches to climate change governance, including international, regional, national and subnational laws and policies; a critical awareness of the broader context of climate change, including issues of globalisation, justice and equity; and an attentiveness to interdisciplinary insights, including a basic understanding of climate science and economics, among other disciplines.

Finally, because climate change reflects and reproduces existing inequalities and vulnerabilities it is also unavoidably an issue of equity and fairness. ‘Climate justice’ draws attention to how the responsibility for anthropocentric climate change is unevenly distributed and that the impacts of climate change will be unequally felt, and that it is often those who contributed least to causing climate change who will suffer most from its effects. Climate justice has various aspects:

- Distributive justice: paying attention to inequalities in the causes, burdens of addressing and experience of impacts.

- Procedural justice: ensuring participatory, accessible, fair and inclusive processes to address climate change.

- Recognition justice: centring voices of those who have historically been marginalised, such as First Nations in Australia.

- Reparative or corrective justice: considering what actions are necessary to redress and repair harms caused.[12]

Thus, an additional legal competency necessary for climate conscious lawyers is attention to the complex, intersecting and cumulative justice issues that climate change enlivens, and how different legal and regulatory measures may accentuate injustice or promote greater equity and fairness.

These competencies have been introduced in this introductory chapter and will be further developed in the forthcoming chapters of this edited collection.

Key Questions

- What do you think ‘climate conscious lawyering’ must involve?

- What are the various competencies you think a ‘climate conscious lawyer’ or legal professional should have?

- How could you best develop these skills and attributes?

- Jan McDonald, ‘Mapping the Legal Landscape of Climate Change Adaptation’ in Tim Bonyhady, Andrew Macintosh and Jan McDonald (eds), Adaptation to Climate Change: Law and Policy (Federation Press 2010), 11. ↵

- Ibid 11. ↵

- Law Council of Australia, Climate Change Policy (Policy Statement, 27 November 2021). ↵

- Ibid 4. ↵

- Law Council of Australia (n 3) 8. ↵

- Ibid 4. ↵

- Brian J Preston, ‘Climate Conscious Lawyering’ (2021) 95(1) Australian Law Journal 51. See also Stephen Tang, Vivien Holmes, and Tony Foley, ‘Ethical Climate, Job Satisfaction and Wellbeing; Observations from an Empirical Study of New Australian Lawyers’ (2020) 33 Georgetown Journal of Legal Ethics 1035; Steven Vaughan, ‘Existential Ethics: Thinking Hard About Lawyer Responsibility for Clients’ Environmental Harms’ (2023) 76(1) Current Legal Problems 1. ↵

- Preston, ‘Climate Conscious Lawyering’ (n 7) 62. ↵

- See further, Julia Dehm, ‘Reconfiguring Environmental Governance in the Green Economy: Extraction, Stewardship and Natural Capital’ in Usha Natarajan and Julia Dehm (eds), Locating Nature: The Making and Unmaking of International Law (Cambridge University Press, 2022) 70–107. ↵

- Michael Mehling, Harro van Asselt, Kati Kulovesi, and Elisa Morgera, ‘Teaching Climate Law: Trends, Methods and Outlook’ (2020) 32 Journal of Environmental Law 417, 433. ↵

- Elizabeth Fisher, Eloise Scotford and Emily Barritt, ‘The Legally Disruptive Nature of Climate Change’ (2017) 80 Modern Law Review 173. ↵

- Monica Taylor and Bronwyn Lay, ‘Community Lawyering and Climate Justice: A New Frontier’ (2022) 47(3) Alternative Law Journal 199. ↵

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are the first peoples of Australia, meaning they were here for thousands of years prior to colonisation. Current research confirms that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have lived on the Australian continent for upwards of 60,000 years. While estimates vary, this figure represents the most widely accepted timeframe based on available evidence. Australia is made up of many different and distinct Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander groups, each with their own culture, language, beliefs and practices. Aboriginal people come from the mainland of Australia and its surrounding islands. The Torres Strait region is located between the tip of Cape York and Papua New Guinea and is made up of over two hundred islands. First Nations is a collective term that refers to Indigenous peoples of a nation, region or place. Indigenous peoples refers to the people with historical and ancestral ties to a place that pre-date colonisation, and is the term used by the United Nations in its Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. All these collective terms can be used respectfully. As proper nouns, all should be used with a capital letter.

A human intervention to reduce emissions or enhance the sinks of greenhouse gases (IPCC, Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change).

The process of adjustment to actual or expected climate and its effects (IPCC, Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability).