4. Motor Vehicle Tax Treatment and Emissions

As noted above, the transport sector is a significant contributor (third largest) to Australia’s GHG emissions and ‘since 2005, transport sector greenhouse gas emissions have increased by 19%’.[1] Decarbonisation of light vehicles, typically cars, motor bikes and light commercial vehicles, is recognised as one of the largest emissions reduction opportunities in Australia. At the time of writing the overwhelming majority of Australian motor vehicles are wholly reliant on fossil fuels, with less than 10% of 2023 sales being electric, representing plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (‘PHEVs’) and battery electric vehicles (‘BEVs’) combined. Further, just 1% of the national fleet is electric.[2] Tax concessions that reward or encourage vehicle use are therefore problematic and will interfere with goals to meet net-zero targets. This is particularly acute in Australia, where the transport sector is such a significant contributor to emissions.[3]

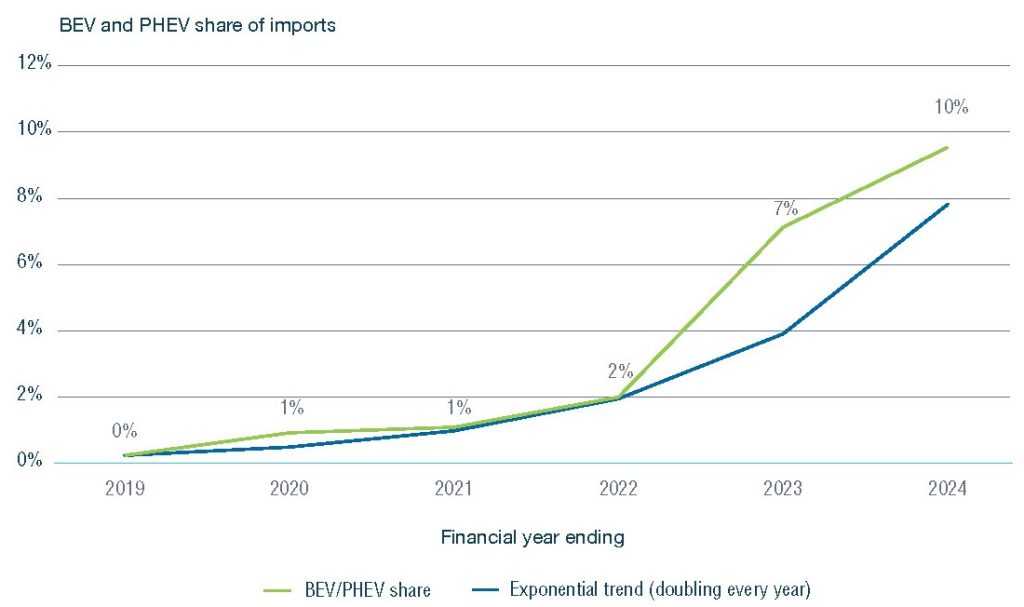

Figure 2 illustrates the recent upward trend in electric vehicle imports. Australia does not have a domestic motor vehicle manufacturing industry; therefore car imports reflect purchases.

We will review some examples of how taxes change behaviour regarding light vehicle purchases and the ways light vehicles are used.

4.1 Fringe Benefits

The fringe benefits tax (‘FBT’) was introduced in 1986 to tax benefits provided to employees by employers that effectively replaced salary and wages. One important feature of the system, the concessional treatment of motor vehicles used for mixed private and work use, had an unintended negative impact on the environment.

The Fringe Benefits Tax Assessment Act 1986 (Cth) (‘FBTAA’) division 2 deals with car fringe benefits. Section 7 defines a car benefit (which is therefore subject to FBT) inter alia as when a car is provided to an employee (or associate of the employee[4]) by the employer (or associate of the employer) and made available for private use of the employee. The concessional treatment of car use by employees produced an unintended negative effect on the environment by encouraging vehicle uptake and use. This derives from the calculation of the taxable value of car fringe benefits, which reduces the overall tax liability and cost of providing a car to an employee and for the employee to use the car. There are two valuation methods available: the FBTAA s 9 statutory formula and the s 10 cost basis. Prior to its amendment in 2011, under the statutory formula method, the calculated value of a fringe benefit from a provided car decreased as the distance travelled by the vehicle increased. This distorted employees’ behaviour by encouraging them to drive further than they would otherwise in order to access the increased tax concession.[5] An amendment in 2011 removed this incentive by introducing a single statutory rate of 20%, regardless of distance travelled.

More recent amendments to the FBTAA in 2022 are designed to incentivise the uptake of electric vehicles by making them more affordable. The Treasury Laws Amendment (Electric Car Discount) Act 2022 (Cth) inserted a new exempt category of car benefits into the FBTAA for cars that are zero- or low-emissions vehicles (see s 8A). A car that meets the definition of a zero- or low-emissions vehicle and is provided for the private use of the employee by the employer is an exempt benefit, thereby attracting no fringe benefits tax. The exemption extends to registration, insurance and maintenance costs but does not extend to purchase and installation of home charging equipment. This measure was explicitly referred to by the Treasurer at the time of introduction as a:

signal to this Parliament , to Australian industry and to the Australian people and beyond, that Australia now has a government which understands the economics of cleaner and cheaper and more reliable energy, and recognises the generational imperative that we have to act on climate change.[6]

This has had a stimulatory effect on the purchase of new electric vehicles. The rate had been flat at less than 1% from 2011 through to 2020 but has jumped to 8.5% of all light motor vehicle sales in 2023[7] (see also Figure 2).

The Treasury Laws Amendment (Electric Car Discount) Act 2022 (Cth) also included a sunset clause in schedule 2 that terminated the exemption for any PHEVs provided by an employer to an employee as a benefit after 1 April 2025. It will not affect any PHEV already concessionally treated, only new car fringe benefit arrangements after this date. The intended effect of this is to further drive down emissions by removing FBT incentives on PHEVs, which use some fossil fuels, while retaining the concessions for BEVs.

KEY QUESTION

- Different concessional FBT treatment for preferred engine or fuel types is one approach to reducing GHG emissions from transportation. Thinking about either FBT or the income tax formula,[8] what are some other ways to incentivise or discourage behaviours that could help reduce GHG emissions from privately owned vehicles such as cars?

4.2 Luxury Car Tax

The luxury car tax also has features that influence consumer behaviour, which has a flow-on effect on emissions. The luxury car tax applies an additional tax of 33% when a new passenger car is first imported, acquired or sold in Australia to the value of the car above the legislated threshold.[9] The current luxury tax threshold for ordinary passenger vehicles for the 2024–25 year is $80,567 whereas the threshold for fuel efficient vehicles is $91,387, thereby making a luxury electric vehicle comparatively less expensive. Another feature of the federal tax system that creates a concession for zero- or low-emissions vehicles is a nil customs duty rate for low-emissions vehicles with a customs value below the luxury car tax threshold (compared to a 5% duty that otherwise would apply).

The luxury car tax, paradoxically, also includes a feature that influences consumer behaviour in a way that results in increased emissions. The luxury car tax definition of a ‘car’ excludes motor vehicles designed to carry a load of more than 2 tonnes or more than nine passengers,[10] as well as commercial vehicles that are not designed for the principal purpose of carrying passengers[11] (ie their principal purpose is to carry goods). Beyond this, there is no legislative definition of a commercial vehicle. The Australian Tax Office has set out a legally binding public ruling to provide a test to determine the principal purpose.[12] Included in the ruling is an appendix that ‘sets out a compliance approach which outlines how the Commissioner [of tax] will allocate compliance resources with respect to this issue’.[13] This is an example of the tax principle of efficiency applying to the administration of a tax. The test of whether a vehicle has a commercial purpose and is therefore exempt from the luxury car tax is broadly ‘whether it can carry twice the weight in payload that it can carry in people’.[14] When this test is applied to utility vehicles or ‘utes’, imported or sold in Australia, they are most often exempt from the luxury car tax, including dual-cab utes capable of carrying five people. The Commissioner will not allocate compliance resources to determine if the vehicle ought to be subject to the tax.[15] Utes are thereby comparatively cheaper to purchase than other vehicles that also exceed the luxury car tax threshold. This pricing disparity incentivises people to choose expensive and larger utes over smaller, more fuel-efficient or electric cars, as the latter vehicles are subject to the luxury car tax, albeit at a higher threshold.[16] Since the introduction of the luxury car tax in 2000, the number of passenger vehicles has grown by half, while the number of light commercial vehicles, including utes, has doubled.[17] As this ‘strong demand for medium/large dual-cab utes [has been for] … large-displacement diesel and petrol combustion engines’,[18] this tax exemption plays a contributing factor to the continued upward trajectory of transport emissions as discussed earlier. An evaluation of the luxury car tax (in this instance the tax concession for commercial vehicles) based on our extra principle of what makes a good tax — climate impact — would undoubtedly judge this to fail that principle.

KEY QUESTIONS

- Which do you think would be more effective in reducing GHG emissions from motor vehicles, keeping in mind tax principles such as administrative efficiency: would you remove from the luxury car tax the exemption for (or otherwise change the definition of) commercial vehicles such as dual-cab utes? Or would you exempt electric vehicles?

- What are the pros and cons of each approach?

- ‘Towards Net Zero for Transport and Infrastructure’, Department of Infrastructure Transport, Regional Development, Communications and the Arts (Cth) (Web Page) <https://www.infrastructure.gov.au/infrastructure-transport-vehicles/towards-net-zero-transport-and-infrastructure>. ↵

- Electric Vehicle Council, Australian Electric Vehicle Industry Recap 2023 (2024) 4. ↵

- Jack Thrower, ‘Luxury Car Tax and the Ute Loophole’ (Report, The Australia Institute, 2024) 1. ↵

- For the purposes of this chapter only the terms employer and employee will be referred to; however, FBT extends to include private use by an associate of the employee such as their spouse and also if there is an agreement between the employer and the provider of the car to provide the car to the employee (or associate). ↵

- Commonwealth, Parliamentary Debates, House of Representatives, 2 June 2011, Treasury Laws Amendment (Electric Car Discount) Bill 2022 (Second Reading Speech) (Bill Shorten, Assistant Treasurer and Minister for Financial Services and Superannuation). ↵

- Commonwealth, Parliamentary Debates, House of Representatives, 27 July 2022, Tax Laws Amendment (2011 Measures No. 5) Bill 2011 (Second Reading Speech) (Jim Chalmers, Treasurer). ↵

- See Climate Change Authority, 2024 Annual Progress Report (Commonwealth of Australia, 2024) 37. ↵

- Income Tax Assessment Act 1997 (Cth) s 4-15(1). ↵

- A New Tax System (Luxury Car Tax) Act 1999 (Cth) (‘LCT Act’). ↵

- Ibid s 27-1 Dictionary meaning of ‘car’. ↵

- Ibid s 25-1(2)(c). ↵

- Australian Taxation Office, Luxury Car Tax: How to Determine the Principal Purpose of a Vehicle (LCTD 2023/1, 23 August 2023) (‘LCTD 2023/1’). ↵

- Ibid [1]. ↵

- Thrower (n 3) 2. ↵

- LCTD 2023/1 (n 13) [60]–[63]. ↵

- Thrower (n 3) 3. ↵

- Ibid 4. ↵

- Terry Martin, ‘VFACTS 2023: Car Industry Breaks All-Time Sales Record’, Carsales (Web Page, 4 January 2024) <https://www.carsales.com.au/editorial/details/vfacts-2023-car-industry-breaks-all-time-sales-record-143992/>. ↵

A Commonwealth government tax paid by employers on non-salary benefits provided to employees or their associates as a reward for services, such as private use of a car or reimbursement of personal expenses. FBT is separate from income tax and is calculated on the grossed-up value of the benefit.[1]

[1] Fringe Benefits Tax Assessment Act 1986 (Cth).