3. How is Law Imagined and How Can It Be Reimagined?

In this section:

- How is law imagined?

- What stories does law tell about itself and the world?

- Is modern law a mythology?

- What would law be if Earth really mattered?

The ideas and values that represent authority, and thereby shape and organise law, emerge from a broader social imaginary. Surrounding and informing the ‘common sense’ idea of law mentioned above is a western (Anglo-European) social imaginary or ‘world view’. Western legal thought has conventionally been understood to be based on reason rather than on stories or myths, but perhaps this itself is a myth.

3.1 How is Law Imagined?

Law and legal thinking have traditionally left no room for ‘reimagin[ing] another law’.[1] Instead, law is conventionally defined by what it excludes, conjuring its own (fictitious) grounds and institutions.[2] Accordingly, law is conventionally understood as self-creating and self-authorising — that is, autonomous. The ways that the stories and myths of western law are represented, for instance in language and in images, reinforce the world view within which they are situated. Stepping back from the world view, myths and representations of western law allows us to begin to develop an awareness of how law is embedded in culture, how non-western traditions operate with different world views, stories and representations, and how the western view of law might be reimagined in a different way.

Imaginaries can be understood as the gathering of different relations with the world, forged through normative practices of knowledge and labour, which constitute realities and sustain authority. Law is one (dominant) representation of social imaginaries, which is not a thing but a relationship understood to exist between humans (subject–subject relation) or between humans and nature (subject–object relation). Lawful relations — or ‘ways of belonging to law’[3] — represent a particular coalescing of social imaginaries, which are articulated and practised in the context of inherited traditions of being and knowing. Philosophers in the western tradition distinguish these as ontology (ways of being) and epistemology (ways of knowing).

Ontology concerns what is and what exists, and an understanding of the relations between these. For example, we can say that the distinction between life and non-life is an ontological division in western philosophy.[4] Epistemology concerns how we know what we know, or the frame of reference for knowing. The relationship between epistemology and ontology is not necessarily straightforward. Epistemology has often been understood as reliant on a human who constructs and ‘knows’ the world with a distinctively human and cultural orientation — but which comes first, human knowledge or the things that are known? For example, western epistemology defines its ontological world view in accordance with a particular binary way of knowing: human and inhuman, culture and nature, masculine and feminine, inside and outside. Because it is difficult to untangle ontology and epistemology, several writers have argued that ways of knowing and ways of being can be understood as co-constituted. Introducing the term ‘onto-epistemology’, Karen Barad says ‘We do not obtain knowledge by standing outside of the world; we know because “we” are of the world.’[5]

The concepts and principles that constitute Australian law are drawn from and remain a part of the dominant social imaginary and its colonial legacies. The authority of law, as law, is generated by and circulated within its social imaginary, assuming authority in its representation and articulation.[6]

3.2 What Stories Does Law Tell About Itself and the World?

Another word for the creation of social imaginaries, and their representation and practice in legal authority and lawful relations, is storytelling. Storytelling practices — imagining, articulating, listening — create social imaginaries and enable their manifestation in law. As we have discussed, law is more than a system of rules and their enforcement; rather, understood as a mode of storytelling, law is a method of creating the meaningful relations that constitute a world view. The story of law and the site of its telling — that is, ‘juris-diction’[7] — combines ontology and epistemology, which coalesce in the exercise and reception of authority. This dominant story entrenches an idea of a singular and unified ‘sovereign will’,[8] its authority epitomised by its central protagonist, the sovereign legal subject.

Storytelling about the origin and meaning of the world, exemplified in theology and politics as well as law, is often described as cosmology. Cosmology describes both ontology and epistemology and refers to a particular understanding of (or storytelling about) normative relations. The term is taken up in scholarly literature to refer to different ways of being and knowing, including Indigenous and First Nations cosmologies, which exist alongside and in relationship with the dominant (western Christian) cosmology.[9] While each cosmology exists among and in relationship with others, in what has been called a ‘pluriverse’,[10] some cosmologies make claims to universality.[11]

Among other things, decoloniality is concerned with the contextualisation and historicisation of ontologies and epistemologies, and an acknowledgement of plural ways of being and knowing. This includes ways of being a legal person, and ways of knowing what law is and what it is for. For critical legal theorists, the social imaginaries that reflect and reinforce ways of being and knowing — ontologies and epistemologies — are reflected in the ways that legal authority is practiced. In turn, the forms and institutions of western law are shaped by a denial of plural ways of being and knowing and the oversimplification of complexity.

This is exemplified in the universalising binaries and abstract reasoning of law. In order to maintain this autonomy, the authority and mechanisms of law — its workings — rely on abstract concepts: for example, the sovereign state, the people, legal personhood, private property and so on. These abstractions presume a distinction and hierarchy between the subjects and objects of law’s authority, and between law itself and the society it governs.

3.3 Is Modern Law a Mythology?

The set of manoeuvres that frames western law has been described by Peter Fitzpatrick as the creation of a ‘mythology’, which is necessary to a world defined by its exclusions.[12] Fitzpatrick explains that one of the central aspects of the mythology of western law is that it is not seen as myth but is rather understood to be based on reason. Another way of thinking about this would be to say that the myths associated with law are so powerful that we cannot see them as myth. We have so thoroughly accepted them as truth that their basis in the stories and representations of western knowledge are invisible to us. Some elements of the western mythology of law (including some discussed by Fitzpatrick) are:

- Law is not myth but based on reason

- Law, based on reason, is ‘progressive’ rather than ‘primitive’ or ‘customary’

- Legal authority, as parliament or sovereign, is elevated above those it governs

- Law is singular and coherent

- Law governs humans, according to human values and for human purposes

- Law is abstract: it affects but is separate from the physical world

For Fitzpatrick, this mythology and its political manifestations — universalism, liberalism, humanism, anthropocentrism — underpin the authority of law and generate the story of its origin. For critical legal theorists, the representation and articulation of law — as storytelling — might be further expressed as the question of ‘who speaks’ and ‘who listens’.[13] The power to speak the law, its ‘juris-diction’, assumes authority in its very articulation. Speaking or declaring law as law arguably brings it into being, which means that the question of who can speak and who listens is important.

In contrast, Indigenous legal scholars have described the authority of Indigenous law as more diffuse but also more grounded. For Kombumerri / Wakka Wakka scholar Mary Graham, authority to speak the law in Indigenous Australian legal traditions is not self-supporting; it is instead embedded in Earth and its multiple relations rather than a single location or articulation.[14] In the western legal tradition, the circularity of authority — how authority is authorised — is conventionally reduced to the question of source. As we have discussed, this may include multiple sources and each might be best understood as a cultural artefact produced over time. Accordingly, the idea of a single source or origin of authority is contested, where the speaking and practice of law can be considered as ‘its own source of authority’.[15]

One way to approach this conundrum is to consider certain cultural artefacts — such as the monarch, the sovereign state, the social contract and societal values — as representations of authority. The construction of law turns on its representation.[16] It is the circulation of ideas, and their consolidation as values, which enable them to come to represent authority and to constitute relations of power.

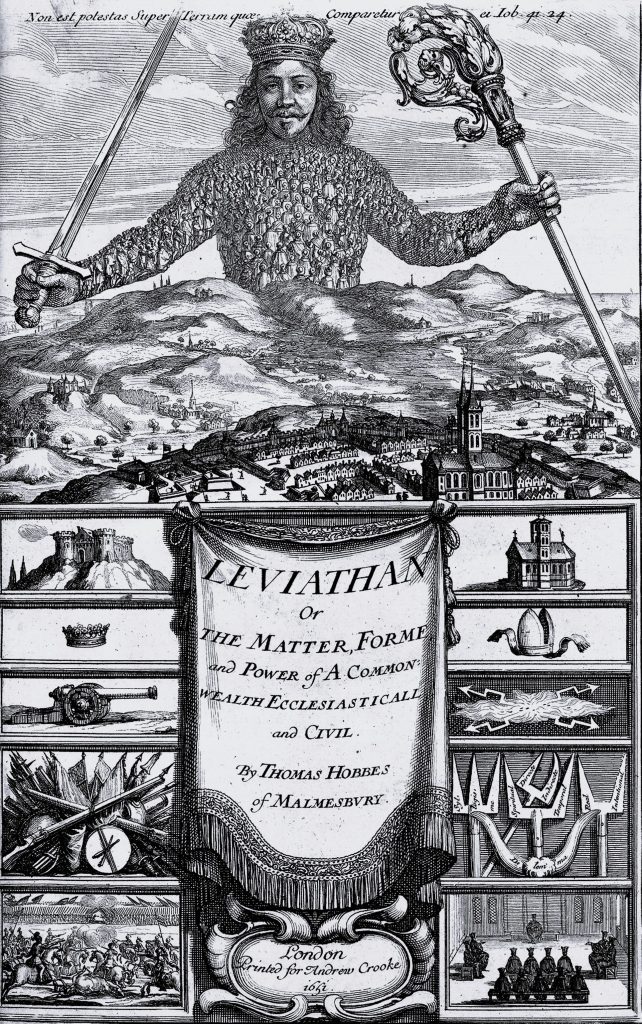

Consider the well-known depiction of sovereign authority (Figure 3), which appeared on the cover of a famous book about the social contract and sovereign rule entitled Leviathan, by Thomas Hobbes (1651). The torso and arms of the central figure are composed of ‘the people’ of the state, over which the sovereign assumes authority. You might consider how authority is represented in this image, and how it might be represented differently. You might also consider the representation of nature in this image, and its relationship to human authority.

We might compare this image of sovereign authority — the biblical and mythical image of the sea serpent, Leviathan, reimagined as the secular sovereign — to the anthropos of the Anthropocene. That is, to the human set apart from all that is presumed to surround them, in a hierarchical relationship between the human (subject) and the non-human (object). This relationship defines the key building blocks of western law, including sovereignty, territory, property and rights. Accordingly, Earth is reduced to being a mere ‘natural resource’ or, alternatively, a ‘pristine wilderness’. Consider the depiction of this relationship in Figure 4. How is Earth depicted? What burden is borne by humanity? How might this idea of nature be imagined otherwise?

Although these images are very different, they both represent human beings and human power as separate from Earth. In contrast, consider the relationality and ‘democracy of feeling’ in Indigenous jurisprudence described by Kombumerri/Munaljahlai scholar Christine Black. In the Yugambeh tradition, the land is the source of the law, which is experienced in the movement of knowledge through storytelling rather than the consequences arising from the exercise of authority.[17]

Indigenous activists and allies have also advocated for Aboriginal land rights through representations of Aboriginal legal authority in public spaces. The Aboriginal Tent Embassy, first established opposite Parliament House in 1972 and subsequently established in multiple locations, exemplifies this rival representation. Similarly, public protest against the grant and exercise of private property rights on Aboriginal country offers an alternative representation of Aboriginal legal authority.

3.4 What Would Law Be If Earth Really Mattered?[18]

Is it possible to imagine law in a way that values the healthy continuation of Earth as a precondition (rather than an afterthought) for flourishing human existence?

As we have discussed, western law has been conventionally understood as a closed system, which is both self-generating and self-authorising.[19] This idea of autonomy emerges from a broader intellectual tradition of liberalism and humanism, which privileges the idea of the autonomous (liberal) subject (human). The rights-bearing liberal subject, which organises western law, is distinguished from its objects, including nature. In the context of escalating ecological degradation, some legal scholars have called for a ‘rethink’ of the traditional role and objectives of rights.[20] While human rights serve an important practical and ethical function, providing minimum standards and fostering accountability, they are also criticised for being anthropocentric, gendered and individualistic, and for ‘creating a false sense of hope’.[21]

Some scholars have advocated an approach that foregrounds ‘earth systems’ in an attempt to reimagine law in ‘planetary terms’ and regulatory spaces as global rather than as sovereign territories.[22] Others have focused on the pursuit of environmental justice, which is principally concerned with equity and distributive fairness.[23] Proponents of this movement have embraced rights, including the right to a healthy environment, as well as rights for nature as discussed previously. One way to approach this conundrum is to think outside of our habitual reliance on rights and to reimagine law as if Earth really mattered.[24] Approaching rights from a theoretical and practical perspective allows us to acknowledge the social imaginaries, or stories, that inform rights and to perceive the limits and possibilities of rights as a tool.

This proposition can be understood as a mode of prefigurative politics — that is, an understanding and enactment of legal and political norms as if a different state of affairs were in fact reality. How might our understanding of legal authority, which is conventionally grounded in the state, change if we accounted for legal norms and authority sourced in nature? How might the privilege attached to rights be understood if our point of departure was instead obligations owed to the non-human world? How might the human protagonist of western law be contextualised by an acknowledgement of plural ways of being and knowing?[25] How might the stories we tell about law change if they were grounded in an idea of law in and as a part of nature?[26] What would it mean to think about law with a consciousness of the limits of human mastery in a changing climate? Becoming a climate conscious lawyer can be understood as an invitation to approach these questions with curiosity and courage, and the knowledge that the law we have imagined can be reimagined.

Key Questions

- How do you imagine and represent law? Can you draw it?

- Does it make sense to think of law in a multi-sensory way? (What would it mean to hear it or touch it?)

- Can you imagine a law where Earth really matters?

- Peter Rush, ‘An Altered Jurisdiction: Corporeal Traces of Law’ (1997) 6 Griffith Law Review 144–68, 150. ↵

- Peter Fitzpatrick, Modernism and the Grounds of Law (Cambridge University Press, 2001); Peter Fitzpatrick, The Mythology of Modern Law (Routledge, 1992). ↵

- Shaunnagh Dorsett and Shaun McVeigh, Jurisdiction (Routledge-Cavendish, 2012) 16; Rush (n 1). ↵

- See Elizabeth Povinelli, Geontologies: A Requiem to Late Liberalism (Duke University Press, 2016). ↵

- Karen Barad, ‘Posthumanist Performativity: Toward an Understanding of How Matter Comes to Matter’ (2003) 28 Signs: Journal of Women in Culture and Society 801–31, 829. ↵

- Rush (n 1). ↵

- Rush (n 1). ↵

- Fitzpatrick, The Mythology of Modern Law (n 2) 54; Kathleen Birrell, ‘Convivial Mythologies: The Poiesis of Modern Law’ (2021) 32 Law & Critique 315–30, 317–18. ↵

- See, eg, CF Black, The Land is the Source of the Law: A Dialogic Encounter with Indigenous Jurisprudence (Routledge, 2011); Walter D Mignolo and Catherine E Walsh, On Decoloniality: Concepts, Analytics, Praxis (Duke University Press, 2018) 135. ↵

- Arturo Escobar, ‘Transition Discourses and the Politics of Relationality: Toward Designs for the Pluriverse’ in Bernd Reiter (ed), Constructing the Pluriverse: The Geopolitics of Knowledge (Duke University Press, 2018). ↵

- For example, Mignolo and Walsh argue that ‘Western Christian philosophers of the European Middle Ages formulated their own local totality in terms of universals’: Mignolo and Walsh (n 9) 164. ↵

- Fitzpatrick, The Mythology of Modern Law (n 2) 42–3. ↵

- Dorsett and McVeigh (n 3); Rush (n 1) 150. ↵

- Mary Graham, ‘The Law of Obligation, Aboriginal Ethics: Australia Becoming, Australia Dreaming’ (2023) 37 parrhesia 1–21. ↵

- Dorsett and McVeigh (n 3) 16. ↵

- Rush (n 1) 144. ↵

- Black (n 9) 178. ↵

- Nicole Rogers and Michelle Maloney (eds), Law as if Earth Really Mattered: The Wild Law Judgment Project (Routledge, 2017). ↵

- Günther Teubner (ed), Autopoietic Law: A New Approach to Law and Society (Walter de Gruyter, 1988) 17–18. ↵

- Louis J Kotzé, ‘Human Rights and the Environment in the Anthropocene’ (2014) 1(3) The Anthropocene Review 252–75, 252. ↵

- Ibid 253, citing David R Boyd, The Environmental Rights Revolution: A Global Study of Constitutions, Human Rights, and the Environment (UBC, 2012) 33–44. ↵

- Louis J Kotzé, ‘Reflections on the Future of Environmental Law Scholarship and Methodology in the Anthropocene’ in Ole W Pedersen (ed), Perspectives on Environmental Law Scholarship: Essays on Purpose, Shape and Direction (Cambridge University Press, 2018) 140–61, 155. ↵

- Lee Godden, Jacqueline Peel and Jan McDonald, Environmental Law (Oxford University Press, 2nd ed, 2018). ↵

- Rogers and Maloney (n 18). ↵

- Kathleen Birrell, ‘The Anthropocene Archive: Human and Inhuman Subjects and Sediments’ in Peter Burdon and James Martel (eds), The Routledge Handbook of Law and the Anthropocene (Routledge, 2023). ↵

- Margaret Davies, EcoLaw: Legality, Life, and the Normativity of Nature (Routledge, 2023). ↵

A field of philosophy/theory that addresses what exists; the theory of being and of what is fundamental to existence. For instance, the question of whether human culture is fundamentally different from nature is an ontological question

A theory of knowledge. Epistemology asks how human beings know what (we think) we know. Is knowledge always socially situated? Is knowledge necessarily subjective?

Encompasses both ontology and epistemology, and refers to a way of understanding normative relations in the world and the universe. The term is often used to refer to a culturally situated way of being and knowing, such as Indigenous cosmology or Christian cosmology, which each offer a distinct account of creation and meaning. While each cosmology exists among and in relationship with others, in what has been called a ‘pluriverse’, some cosmologies make claims to universality. Cosmology also refers to the western scientific study of the universe and its origins.

Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are the first peoples of Australia, meaning they were here for thousands of years prior to colonisation. Current research confirms that Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples have lived on the Australian continent for upwards of 60,000 years. While estimates vary, this figure represents the most widely accepted timeframe based on available evidence. Australia is made up of many different and distinct Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander groups, each with their own culture, language, beliefs and practices. Aboriginal people come from the mainland of Australia and its surrounding islands. The Torres Strait region is located between the tip of Cape York and Papua New Guinea and is made up of over two hundred islands. First Nations is a collective term that refers to Indigenous peoples of a nation, region or place. Indigenous peoples refers to the people with historical and ancestral ties to a place that pre-date colonisation, and is the term used by the United Nations in its Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. All these collective terms can be used respectfully. As proper nouns, all should be used with a capital letter.

This is a cultural, legal and philosophical foundation for First Nations people that encompasses the central relationships of life and extends to people and to Country. It embeds the notion of shared responsibility and ongoing obligations.