3. Future Trajectories of Australian Constitutional Law

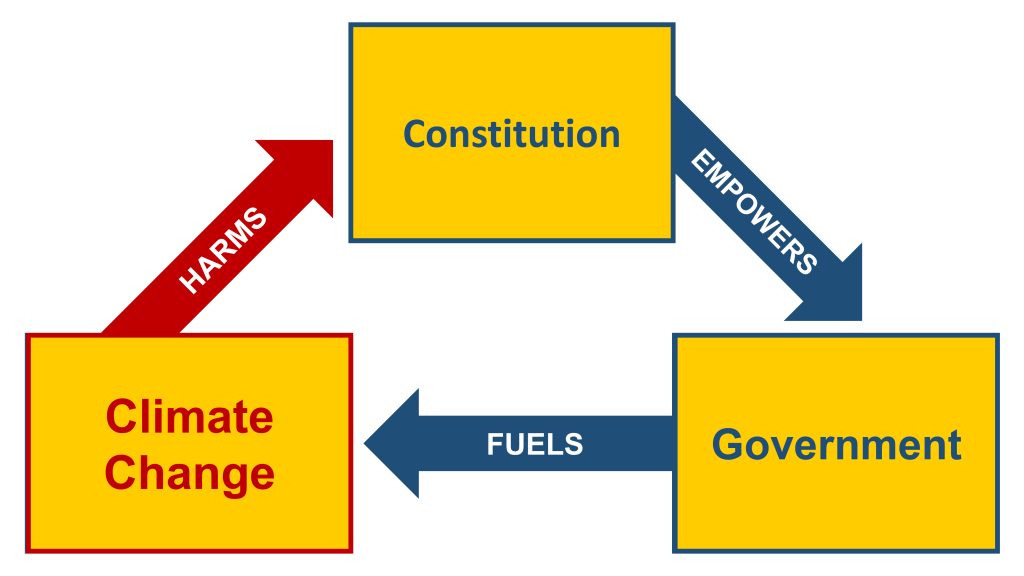

As noted in part 2.1, the Constitution embodies a model of political constitutionalism for rights protections.[1] This generally means that people rely more on political processes than judicial enforcement of constitutional limitations to compel governments to respond to issues like climate change. Australia has a history of strong environmental protest movements that have successfully influenced legislatures. For instance, such a movement was instrumental in pushing the Commonwealth to stop the damming of the Franklin River, the subject of the Tasmanian Dam Case discussed in part 1.3. However, many climate advocates wonder whether political processes are sufficient in the current climate context. Australia continues to rank among the world’s worst climate actors, despite decades of protests, lobbying, media scrutiny and more.[2] The fossil fuel industry exercises considerable influence over Commonwealth and state governments. Some have described this influence, which has seen climate laws and policies continually weakened or abandoned and anti-protest laws strengthened, as an example of ‘corporate state capture’.[3] With more than three decades largely squandered, time is now running out before dangerous climate tipping points are reached.[4]

Climate advocates should utilise the political mechanisms available under the Constitution to their full extent. The last 30 years of experience, however, suggests that additional legal mechanisms are needed. In this part, we explore two potential developments. First, we consider whether the High Court might uncover an implication within the text and structure of the Constitution to help address climate wrongdoing. Second, we examine the feasibility of amending the Constitution to explicitly include environmental protections.

3.1 Constitutional Implications

Language requires interpretation. When resolving disputes over the meaning of a constitutional provision, the High Court will start by construing the text. However, that text may contain not only a range of possible meanings but also a ‘spectrum of implications’ based on context and purpose.[5] Over the years, the High Court has found several implications within the text and structure of the Constitution. For example, we discussed in part 2.3 that drawing on provisions that mandate that the legislative and executive branches of government are ‘ultimately answerable to the Australian people’,[6] the Court has held that the Constitution implicitly protects freedom of political communication as ‘indispensable to that accountability’.[7] Likewise, drawing on the federal nature of the Constitution, the High Court has found limits to Commonwealth legislative power. The Melbourne Corporations principle prevents the Commonwealth from making laws which destroy or significantly burden or weaken the capacity of the states to carry out or exercise their legislative, executive and judicial functions.[8] Could a constitutional implication that protects the environment be uncovered?

Courts in at least 20 nations, including Argentina, Greece, India, Kenya and Malaysia, have found environmental protections implied in their constitutions.[9] The common rationale is that a right to a healthy environment and/or climate is a fundamental component of explicit constitutional rights, such as the right to life or right to health.[10] In Leghari v Pakistan, for example, the High Court of Lahore held that the Pakistani government’s failure to implement its climate policies violated the constitutional rights of its citizens, including the right to life, right to human dignity, right to property and right to information.[11] The Court held that these rights provided ‘the necessary judicial toolkit to address and monitor the Government’s response to climate change’.[12]

As this suggests, implications require fertile soil. The absence of rights protections in Australia’s Constitution might appear to leave courts tilling a barren text.[13] However, some pathways forward have been suggested. For instance, Costa Avgoustinos proposes that an ‘implied right to a healthy environment’ (or ‘ecological limitation’) may be found within the text and structure of the Constitution.[14] Avgoustinos notes that the implied freedom and Melbourne Corporations principle aim to secure the structural integrity of the Australian constitutional system. He argues that Commonwealth and state activity worsening climate change (such as government approval of a new coalmine) may be viewed as posing a threat to our constitutional system. This is because the overlapping crises of escalating temperatures, disease, natural disasters, food and water insecurity and more may impair, if not destroy, state relationships, parliamentary and electoral processes, court functions and other fundamental aspects of the Australian constitutional system in the coming decades and centuries.[15] For this reason, an ecological limitation could be uncovered. Indeed, as NSW Supreme Court judge François Kunc states, ‘inadequately mitigated climate change could undo our social order and the rule of law itself’.[16]

Other approaches have also been proposed. Section 100 of the Constitution provides that the Commonwealth shall not abridge the right of a state or its residents to reasonable use of waters. Although the section ‘is silent on the rights of State inter se’, Nicholas Kelly has argued that it could carry an implied limit on water use by the states.[17] Adam Webster has made a similar argument, drawn from the Melbourne Corporations principle. Webster suggests that the maintenance of the Constitution’s federal balance might extend to restraining one or more states depriving another of water in certain transboundary river disputes.[18] This has particular salience in the context of climate change’s expected detrimental impacts on the Murray–Darling Basin water supply.

Consider one more possible implication. In 2009, Steven Gageler (now Chief Justice of the High Court) outlined a persuasive vision of the Constitution based in the principles of representative and responsible government. The vision expounded by Gageler gives an understanding of political accountability as the primary method of constraining government power but sees judicial power as ‘tailoring itself to the strengths and weaknesses’ of the ordinary method.[19] This rationale explains ‘the broad sweep of constitutional doctrine’, including when and why the Court has uncovered constitutional implications.[20] Could this vision justify an environmental implication along the lines proposed by Costa Avgoustinos above? The severity and impact of the climate crisis is delayed; the young and future generations will be left to respond to its worst effects. Yet, because they are not eligible to vote, these groups are unable to employ the political mechanisms available under the Constitution to protect their interests now when it matters most. In Theophanous v Herald & Weekly Times Ltd, McHugh J noted that the Constitution is an intergenerational compact ‘intended to endure for centuries’.[21] The interests of future generations, and the deficiencies of our political processes to address them in the context of the climate crisis, cannot be dismissed.

It is beyond the scope of this chapter to examine whether these arguments might succeed in litigation. It is important to note, however, that the High Court has historically been hesitant to derive new implications from the Constitution or extend existing implications too far. Such hesitancy reflects concerns over the proper development of constitutional jurisprudence and democratic legitimacy. After all, the Constitution contains its own method for amendment in section 128.[22] Nevertheless, the Court’s general position is that constitutional implications are a legitimate, and unavoidable, aspect of constitutional jurisprudence.[23] This is because, as Dixon J explains, written constitutions must be ‘expressed in general propositions wide enough to be capable of flexible application to changing circumstances’.[24] Perhaps the cumulative effect of the climate crisis might encourage — or compel — a future court to read the Constitution in a new way, responsive to radically changed circumstances.

KEY QUESTIONS

- Can you think of other implications that might be drawn from the text and structure of the Constitution relevant to the climate crisis?

- What institutional constraints must courts manage when considering whether to draw an implication from the text and structure of the Constitution?

3.2 Constitutional Amendment

Discerning an environmental implication within the text and structure of the Constitution may be challenging. It would also likely attract criticism as a particularly ‘inventive judicial decision’.[25] A more formal approach to reform would follow the process outlined in s 128, which gives the Australian people the opportunity to decide. Section 128 sets out the process by which the Constitution may altered. It imposes three steps.

- A bill to amend the Constitution must be passed by the Parliament (or passed by the same House twice within a period of six months). The bill is then submitted to the Australian electors.

- The bill must obtain an absolute majority of voters; and

- The bill must also obtain a majority of voters in a majority of states (ie four out of six states must approve the alteration).

Constitutional amendment has proven difficult. Of the 45 attempts to amend the Constitution since 1901, only eight proposals have succeeded. The last amendment was made in 1977. This record suggests that any attempt to bolster environmental protection at the federal level will be challenging.

The Australian Constitution stands increasingly isolated in its failure to incorporate provisions requiring governments to undertake environmental protection or limits on government power to restrict environmental degradation. A majority of nations (157 out of 193) have constitutions that include environmental protection provisions.[26] These include duties placed on governments to protect the environment,[27] rights of citizens to a healthy environment[28] and rights of nature itself to flourish.[29] The constitutions of 12 nations even refer to climate change explicitly.[30]

Climate litigants across the world have used the environmental protection provisions in their respective national constitutions to tackle climate change. In Colombia, for example, the Constitutional Court struck down two laws that threatened the nation’s páramos, resulting in the revocation of hundreds of mining licences.[31] These alpine tundra ecosystems operate as carbon sinks and provide Colombia with up to 70% of its drinking water. The Court emphasised that climate change and its impacts on water security may make this water supply even more valuable in the future.[32] The Court’s decision relied, in part, on the breach of the public’s constitutional right to clean water and the government’s constitutional obligations to justify decisions that degrade environmentally sensitive and valuable areas.

Similarly, in the landmark case of Urgenda v Netherlands, the Hague District Court drew on environmental protection obligations in the Dutch Constitution to help establish the government’s ‘duty of care’ to take climate action in tort law.[33] Article 21 of the constitution states that: ‘It shall be the concern of the authorities to keep the country habitable and to protect and improve the environment’. The court held that although Urgenda, a Dutch environmental group, cannot derive rights from this constitutional provision directly, the provision was relevant to the question of whether the state had failed to meet its duty of care to Urgenda. Similar reasoning has been, and is currently being, pursued in climate litigation in other jurisdictions.[34]

If Australia is to adopt a provision on environmental protection in the Constitution, what approach should it take? Some scholars have suggested that a right to a healthy environment could be entrenched in the document on its own or as part of a broader Bill of Rights.[35] In August 2024, for example, the ACT Legislative Assembly passed legislation to add a ‘right to a healthy environment’ into its statutory Human Rights Act 2004.[36]

However, a right to a ‘healthy environment’ is aspirational and broad. A court required to determine whether some government action, such as permitting the construction of a mine or failing to legislate sufficiently robust carbon emissions targets, may struggle to clearly resolve the dispute. It is likely that the right will be found to be subject to an express or implied limitation or otherwise limited through a balancing exercise. The risk for climate activists is that the indeterminate and ambiguously worded right will be read down.

Ron Levy has argued that a better approach is to insert a provision that provides a fixed constitutional commitment.[37] These provisions impose precise, binding and entrenched obligations. Several examples exist. The Victorian constitutional prohibition on fracking, discussed above, imposes a clear ban on the practice. Similarly, in Bhutan and Kenya, constitutional provisions require a set percentage of forest cover (60% and 10%, respectively).[38] While these two cases are somewhat ambiguous (what counts as forest?), they seek to establish a clearly defined baseline through which government can be held to account.

KEY QUESTIONS

- Why do you think most constitutional amendments in Australia have failed?

- Why do you think the Australian Constitution differs in this regard from that of other countries?

- Can you think of a fixed environmental constitutional commitment for Australia?

Constitutional amendment is simpler at the state level. This is because state constitutions are flexible and capable of being amended by passage of ordinary legislation.[39] Given the ease with which amendments can be made, state Parliaments may choose to entrench climate protection legislation through constitutional amendment. In 2021, for example, the Victorian Parliament amended the Victorian Constitution to constrain the power of the Parliament to make laws repealing or altering a ban on fracking, coal seam gas exploration and mining.[40]

However, the flexibility of state constitutions means the effect of this entrenchment is uncertain.[41] State Parliaments may only entrench legislation through manner and form provisions, which are only valid in relation to laws relating to the ‘constitution, powers or procedure of the Parliament’. The Victorian constitutional provision noted above does not relate to the composition, powers or procedure of the Parliament and is likely of no legal effect.

KEY QUESTIONS

- If the Victorian constitutional prohibition on fracking is of no legal effect, why did the Victorian Parliament amend the Victorian constitution? Does state constitutional amendment serve broader goals?

- For further discussion on the political constitutionalist model and its impact on climate governance in Australia see the chapter in this publication by Gabrielle Appleby and Joo-Cheong Tham on ‘Public Law and Climate Conscious Lawyering’ (specifically, the section on ‘How Australian Public Law Shapes the Sites and Conceptions of Climate Action’). ↵

- Australia ranks 54 out of 61 nations (including the European Union as a whole) in the Climate Change Performance Index: Jan Burck et al, ‘Climate Change Performance Index Results 2021’ (Germanwatch, New Climate Institute and Climate Action Network, December 2020) 7. Note that the three top positions are left blank on the ranking as ‘(n)o country is doing enough to prevent dangerous climate change’: 7. ↵

- See, eg, Adam Lucas, ‘Investigating Networks of Corporate Influence on Government Decision-Making: The Case of Australia’s Climate Change and Energy Policies’ (2021) 81 Energy Research & Social Science (article 102271). ↵

- Haydn Washington and John Cook, Climate Change Denial: Heads in the Sand (Earthscan, 2011) 30–1. A global temperature of 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels is broadly held to demarcate when the risk of generating runaway climate change substantially increases. ↵

- James Edelman, ‘Implications’ (2022) 96 Australian Law Journal 800, 802. ↵

- Nationwide News v Wills (1992) 177 CLR 1, 47 [17] (Brennan J). ↵

- ACTV v Commonwealth (1992) 177 CLR 106, 138 [38] (Mason CJ). ↵

- Melbourne Corporations v Commonwealth (1947) 74 CLR 31. ↵

- David Boyd, The Right to a Healthy Environment: Revitalizing Canada’s Constitution (UBC Press, 2012) 86–8. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Leghari v Pakistan (High Court of Lahore, WP No 25501/2015, 4 September 2015). ↵

- Ibid [7]; Justice Rachel Pepper, ‘Climate Change Litigation: A Comparison between Current Australian and International Jurisprudence’ (2017) 13 Judicial Review 329, 338–9. ↵

- Rachel Pepper and Harry Hobbs, ‘The Environment is All Rights: Human Rights, Constitutional Rights and Environmental Rights’ (2020) 44(2) Melbourne University Law Review 634, 669–73. ↵

- Costa Avgoustinos, ‘Climate Change and the Constitution: The Case for the Ecological Limitation’ (2023) 49(1) Monash University Law Review 267. ↵

- Constantine Avgoustinos, ‘Climate Change and the Australian Constitution: The Case for the Ecological Limitation (PhD Thesis, University of New South Wales, 2020) 196–202 <http://hdl.handle.net/1959.4/65521>. ↵

- François Kunc, ‘Climate Change May Pose Threat to Rule of Law, Says Supreme Court Judge Francois Kunc’, Australian Financial Review (online, 11 October 2018) <www.afr.com/business/legal/climate-change-poses-threat-to-rule-of-law-says-supreme-court-judge-francois-kunc-20181011-h16iov>. Oregan District Court judge, Aiken J, similarly stated that she had ‘no doubt that the right to a climate system capable of sustaining human life is fundamental to a free and ordered society’: Juliana v United States, 217 F Supp 3d 1224 (D Or 2016), 1251. ↵

- Nicholas Kelly, ‘A Bridge? The Troubled History of Inter-State Water Resources and Constitutional Limitations on State Water Use’ (2007) 30(3) University of New South Wales Law Journal 639. ↵

- Adam Webster, ‘Sharing Water from Transboundary Rivers: Limits on State Power’ (2016) 44 Federal Law Review 25, 36–47. See also Adam Webster, ‘Sharing Water from Transboundary Rivers in Australia — An Interstate Common Law?’ (2015) 39 Melbourne University Law Review 263. ↵

- Stephen Gageler, ‘Beyond the Text: A Vision of the Structure and Function of the Constitution’ (2009) Bar News: Journal of the NSW Bar Association 30, 37. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- (1994) 182 CLR 104, 196. For discussion on the connection between constitutions and the future generations they serve see Karen Schultz, ‘Future Citizens or Intergenerational Aliens? Limits of Australian Constitutional Citizenship’ (2012) 21 Griffith Law Review 36; Richard Hiskes, The Human Right to a Green Future: Environmental Rights and Intergenerational Justice (Cambridge University Press, 2009) 126–33. ↵

- See, eg, Jeffrey Goldsworthy, ‘Constitutional Implications Revisited’ (2011) 30(1) University of Queensland Law Journal 9. ↵

- West v Commissioner of Taxation (NSW) (1937) 56 CLR 657, 681; Leslie Zines, ‘Sir Owen Dixon’s Theory of Federalism’ (1965) 1 Federal Law Review 221, 223–4. ↵

- Australian National Airways Pty Ltd v Commonwealth (1945) 71 CLR 29, 81. ↵

- Goldsworthy (n 22) 9. ↵

- Constitute Project (Web Page) <constituteproject.org>. For discussion see United Nations Environment Programme, Environmental Rule of Law: First Global Report (2019); Boyd (n 9). ↵

- Boyd (n 9) 73–4. ↵

- Ibid 74–8. ↵

- Constitution of the Republic of Ecuador art 414; Constitution of the Plurinational State of Bolivia 2009 art 108.16 — see also the Framework Law of Mother Earth and Integral Development for Living Well 2012 (Bolivia). ↵

- Karla Martinez Toral et al, ‘The 11 Nations Heralding a New Dawn Of Climate Constitutionalism’, LSE (online, 2 December 2021) <https://www.lse.ac.uk/granthaminstitute/news/the-11-nations-heralding-a-new-dawn-of-climate-constitutionalism>. These nations are Algeria, Bolivia, Côte d’Ivoire, Cuba, Dominican Republic, Ecuador, Thailand, Tunisia, Venezuela, Vietnam and Zambia. ↵

- Sentencia (Decision C-035/16), Constitutional Court of Colombia, 8 February 2016. Law No. 1450 of 2011 authorised the Commission on Intersectoral Infrastructure and Strategic Projects to class specific projects as exempt from particular local regulation. Law No. 1753 of 2015 prohibited particular activities in the páramos, such as mining, unless authorised prior to certain dates. ↵

- United Nations Environment Programme, ‘The Status of Climate Change Litigation — A Global Review’ (United Nations Environment Programme, May 2017) 19. ↵

- Urgenda v Netherlands (Hague District Court, ECLI:NL:RBDHA:2015:7196, 24 June 2015) [4.52]. ↵

- For discussion see Lucy Maxwell, Sarah Mead and Dennis van Berkel, ‘Standards for Adjudicating the Next Generation of Urgenda-Style Climate Cases’ (2022) 13 Journal of Human Rights and the Environment 35. ↵

- Mary Emily Good, Legal Recognition of the Human Right to a Healthy Environment as a Tool for Environmental Protection in Australia: Useful, Redundant, or Dangerous? (PhD Thesis, University of Tasmania, 2016) 183–98. See also Daniel Goldsworthy, ‘Re-Stumping Australia’s Constitution: A Case for Environmental Recognition’ (2017) Australian Journal of Environmental Law 53. ↵

- Human Rights (Healthy Environment) Amendment Act 2024 (ACT), inserting s 27C into the Human Rights Act 2004 (ACT). ↵

- Ron Levy, ‘Fixed Constitutional Commitments: Evaluating Environmental Constitutionalism’s “New Frontier”’ (2022) 46(1) Melbourne University Law Review 82. ↵

- See Constitution of the Kingdom of Bhutan 2008 art 5(3); Constitution of Kenya 2010 art 69(1)(b). ↵

- McCawley v The King [1920] AC 691. ↵

- Constitution Act 1975 (Vic), pt VIII. ↵

- See Greg Taylor, The Constitution of Victoria (Federation Press, 2006) 470–520. ↵

An approach to drafting a constitution that emphasises political institutions and processes to hold governments accountable. The expectation is that political means, such as public debate and parliamentary scrutiny, will effectively weed out government wrongdoing. This contrasts with constitutions written in a legal constitutionalist model. Such constitutions typically include more detailed limits on government power to be enforced by courts.

Provisions in a constitution that require governments to undertake environmental protection or limits on government power to restrict environmental degradation. These include duties placed on governments to protect the environment, rights of citizens to a healthy environment and rights of nature itself to flourish.