3. Climate Law

Given all that is at stake, it is unsurprising that ‘climate law’ has emerged as a specialised field of international law. International climate change law is based on three international law treaties — the 1992 United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC),[1] the 1997 Kyoto Protocol[2] and the 2015 Paris Agreement[3] — as well as the annual Conference of the Parties (COP) as the main decision-making body of the UNFCCC, subsidiary institutions and mechanisms, and the decisions and practices adopted therein. International climate change law interacts with many other fields of international law and has implications for almost all aspect of states’ national policies, including energy, agriculture, transportation, disaster planning and health. In this context, most states have adopted laws and policies that govern action on climate change, generally relating to mitigating GHG emissions, adapting to the impacts of climate change, and disaster risk management.[4] A subset of those domestic laws and policies link national and international action on climate change. The next section of the chapter will briefly describe the field of international climate change law and introduce Australia’s approach to linking its international obligations with national laws and policies.

3.1 International Climate Change Law

The 1992 UNFCCC acknowledges that “‘change in the Earth’s climate and its adverse effects are a common concern of humankind”’.[5] The Convention sets out key principles that are intended to inform and guide the development of subsequent treaties, including that parties to the Convention should protect the climate on the basis of equity and in accordance with their “‘common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities”’.[6] It also highlights the “‘specific needs and special circumstances of developing country Parties”’, especially those “‘particularly vulnerable to the effects of climate change”’,[7] and the need for “‘precautionary measures”’.[8]

In the negotiation of the UNFCCC, state parties were unable to agree on specific legally binding emission reduction targets. In light of this, the UNFCCC primarily set out some general obligations and established institutions and processes, including subsidiary bodies, a secretariat and annual conferences (the COP) to allow for ongoing negotiations and norm development under the framework Convention. The UNFCCC created obligations for all parties to develop and publish national inventories and formulate and implement programs containing measures to mitigate climate change by addressing emissions from sources and removals by sinks.[9] It also created further obligations for countries listed in Annex I of the Convention (industrialised countries that were part of the OECD, the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, in 1992 and countries with economies in transition) to adopt national policies and take corresponding measures to limit emissions of GHGs and protect and enhance sinks.[10] Finally, the UNFCCC created additional obligations for countries listed in Annex II (just the industrialised countries that were part of the OECD in 1992) relating to the provision of financial resources and technology transfer to support developing country parties, especially those that are particularly vulnerable to climate change.[11]

The subsequent 1997 Kyoto Protocol established some binding reduction commitments for Annex I, the developed countries party to the original Convention. In total, the Protocol sought to reduce overall GHG emission by at least 5 per cent below 1990 levels during its first commitment period (2008–2012).[12] The quantified emission limitation or reduction commitments for each developed country was listed in Annex B. Australia was able to negotiate significant concessions at Kyoto: while other developed countries committed to emission reductions, Australia negotiated an agreed target that would allow it to increase its emissions by 8 per cent over the first commitment period (2008–2012). Another major concession was the so-called Australia clause (Article 3.3), which allowed Australia to obtain credit for reductions in land clearing since 1990 that were caused by separate policy changes. Despite negotiating an increasingly favourable deal, the Coalition government of Australia at the time, headed by Prime Minister John Howard, choose not to ratify the Kyoto Protocol. It was not until 2007 that Australia ratified the Protocol, after the election of the Labor Party led by Prime Minister Kevin Rudd.

The Kyoto Protocol also established an international system of carbon trading,[13] including two carbon offset schemes, ‘Joint Implementation’[14] and the ‘Clean Development Mechanism’.[15] The former allowed developed country parties to support emission reduction in other developed country parties and in return allow the resulting emission reduction units from the project to be counted towards its own emission reduction commitments. The Clean Development Mechanism allowed developed country parties to support emission reduction projects in developing countries and in return allow the resulting certified emission reductions from the project to be counted towards its own emission reduction commitments. The Clean Development Mechanism was intended to generate win-win outcomes for developed and developing country parties, as well as the climate, but has been heavily criticised for failing to generate real and additional emission reductions and, at times, for contributing to negative human rights and social impacts where the projects were located.[16]

The Kyoto Protocol did not come into force until 2005; however, the focus of international negotiations had already moved to what would come after it. The 2007 Bali Action Plan launched a “‘process to enable the full, effective and sustained implementation of the Convention”’ up to and beyond 2012.[17] This process sought to address a shared vision for long-term cooperative action, as well as enhanced action on mitigation, adaptation, technology development, and transfer and provision of financial resources and investment to support action. There were high hopes that a post-2012 agreement would be reached at COP15 held in Copenhagen in 2009; however, the conference only produced the controversial ‘Copenhagen Accord’, which was ‘noted’ but not adopted by the COP.[18] However, a few years later in 2011 a last-minute breakthrough in Durban saw a commitment to “‘develop a protocol, another legal instrument or an agreed outcome with legal force under the Convention applicable to all Parties”’ by 2015.[19]

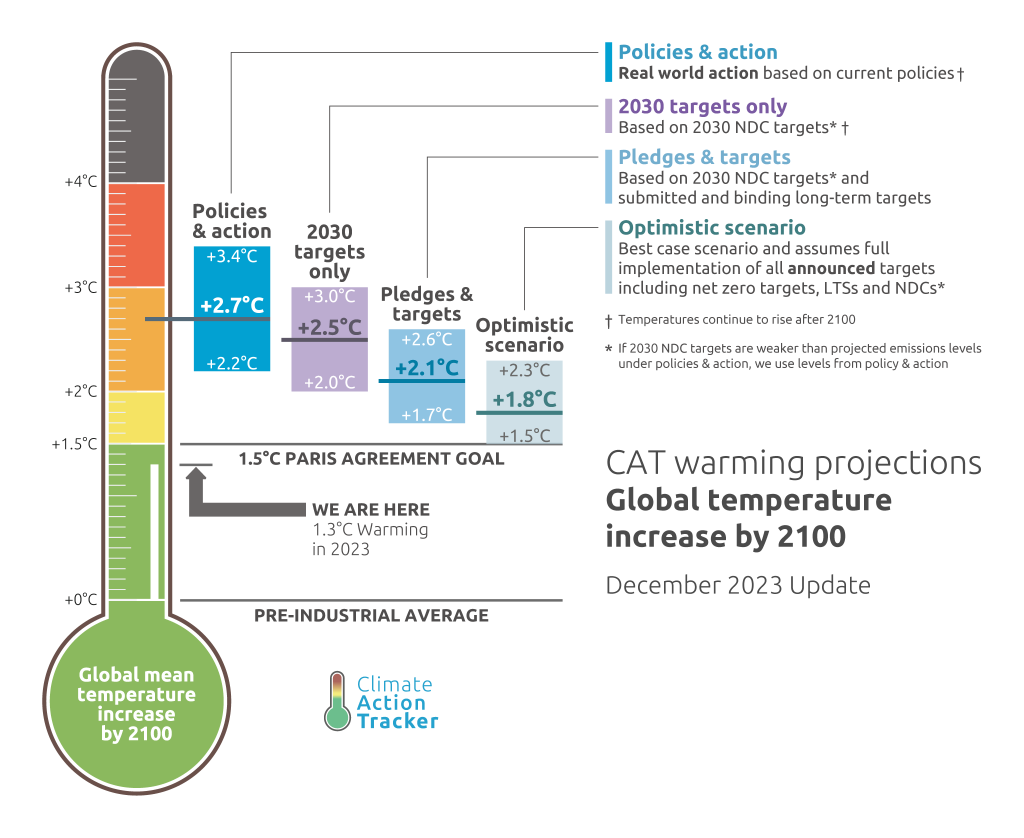

The subsequent 2015 Paris Agreement was widely celebrated as a ‘landmark’ and ‘historical’ agreement, even though climate justice groups simultaneously warned that it was an “‘accord that failed humanity”’ and a “‘disaster for the world’s most vulnerable and future generations”’.[20] The Paris Agreement sets out a number of key objectives, including “‘holding the increase in the global average temperature to well below 2 °C above pre-industrial levels and pursuing efforts to limit the temperature increase to 1.5 °C above pre-industrial levels”’.[21] Its objectives also include increasing the capacity to adapt to the adverse impacts of climate change[22] and directing finance towards GHG emission reductions and climate-resilient development.[23] In contrast to the Kyoto Protocol, the Paris Agreement adopts a more ‘bottom up’ architecture and allows each country to put forward their own intended ‘nationally determined contributions’ (NDCs) — intended plans of action to reduce GHG emissions and adapt to the adverse impacts of climate change.[24] State parties are required to submit an NDC every five years,[25] each reflecting a progression on their previous NDC and reflecting the particular country’s “‘highest possible ambition”’.[26] Additionally, a “‘global stocktake”’ on collective progress towards achieving the objective of the Paris Agreement will be held every five years.[27] The first global stocktake concluded in 2023, underlining that there remains a problematic gap between the NDCs put forward by state parties and the emission reductions necessary to stay within the global temperature limit set out under the Paris Agreement (see Figure 32).[28]

The Paris Agreement also includes provisions on adaptation (Article 7), loss and damage (Article 8), finance (Article 9), technology transfer (Article 10) and capacity building (Article 11). More specifically, Article 7 sets out “‘the global goal on adaptation of enhancing adaptive capacity, strengthening resilience and reducing vulnerability to climate change”’, taking into account the sustainable development needs of state parties and the temperature limit in Article 2 of the agreement.[29]

Despite mitigation and adaptation action, some losses and damages associated with climate change have already occurred and will continue to occur into the future. In Article 8 of the Paris Agreement, state parties “‘recognized the importance of averting, minimizing, and addressing loss and damage associated with the adverse effects of climate change”’.[30] Articles 9, 10 and 11 reaffirm that developed country parties must help developing countries in mitigation and adaptation by providing financial assistance, technology transfer and capacity-building support, respectively.[31]

The international climate treaties have been surprisingly silent on the main causes of global climate change, namely the burning of fossil fuels. Although the 1988 Toronto Conference on the Changing Atmosphere had already recommended that half of all emission reductions should come from decreasing fossil fuel supply,[32] the UNFCCC and Paris Agreement do not include any commitment to reduce fossil fuel extraction or combustion. A key outcome of the 2021 Glasgow Climate Pact[33] was a reference to “‘accelerating efforts towards the phasedown of unabated coal power and phase-out of inefficient fossil fuel subsidies”’.[34] The question of fossil fuels was central to the negotiations at COP28 in Dubai; however, the final text only called on parties to take action, including “‘[a]ccelerating efforts towards the phase-down of unabated coal power”’, “‘[t]ransitioning away from fossil fuels in energy systems”’ and “‘[p]hasing out inefficient fossil fuel subsidies that do not address energy poverty or just transitions”’.[35]

Key Questions

- Do you think the international legal climate regime is adequately and equitably addressing the challenge of climate change? Why/why not?

- What additional or changed legal frameworks do you think might be needed?

3.2 Australia’s Climate Change Laws and Policies

There are many compelling reasons for Australia to take strong and ambitious climate action. Australia has a high level of vulnerability to climate impacts, especially extreme weather events such as floods and fires.[36] Moreover, economic assessments have consistently shown that ‘business as usual’ is not a viable option and that the costs of acting will increase the longer we delay.[37] Finally, Australia has many opportunities to benefit from and be a global leader in the transition to a low-carbon society.[38] Yet despite this, Australia has historically been a ‘laggard’ not a ‘leader’ on climate policy.[39]

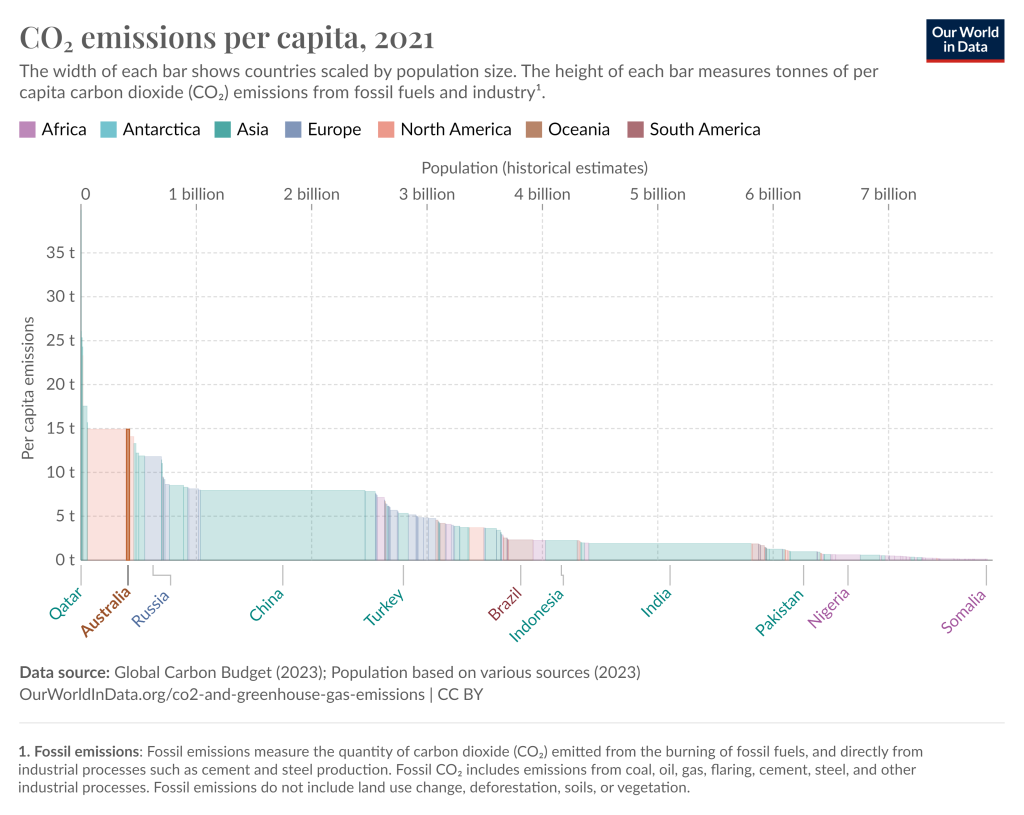

Australia has one of the higher levels of per capita GHG emissions in the world: 15.1 tonnes in 2021, which is almost double China’s 8 tonnes per capita, or 50 times the per capita emissions of low-income countries (see Figure 43).[40] This is due to the high reliance on coal and gas in Australia’s energy portfolio, GHG emissions from coal mines, and the degradation of carbon sequestration in soils and forestry through agricultural activities and other land-use changes. Australia’s largest contribution to global climate change is through its exports of fossil fuels, especially coal and gas. Australia has some of the largest coal reserves in the world and is the second largest coal exporter internationally.[41] The emissions from Australian coal that is burnt overseas are almost double our domestic emissions.[42] Australia is also the world’s largest liquefied natural gas exporter.[43]

A recent Oil Change International report, Planet Wreckers, shows that just 20 countries are likely to be responsible for almost 90 per cent of the carbon pollution from new coal and gas fields between 2035 and 2050, and over 50 per cent of this planned expansion comes from five countries: Australia, the United States, Canada, Norway and the United Kingdom. However, there remains bipartisan support for fossil fuel production in Australia and there is “‘no national policy framework aiming to restrict fossil fuel exploration, production, or infrastructure development”’.[44] Australian policy has thus long been blinded by a “‘quarry vision”’[45] and fossil fuel industries have “‘constructed a covert network of lobbyists and revolving door appointments which has ensured that industry interests continue to dominate Australia’s energy policy”’.[46] As the United Nations Environment Program Production Gap Report 2023 notes, “‘coal and gas industries have strong influence in political debate, diplomacy, economic strategy, and policy development, both nationally and in fossil-fuel-exporting states”’.[47]

Climate policy is historically contentious and politically fraught in Australia: there has been a lack of bipartisan consensus about climate action, and climate debates have been a catalyst for change in government and internal party leadership in both major parties. The period from around 2007 to 2023 is often characterised at the ‘climate wars’. There were several unsuccessful attempts to introduce a national climate policy, including the Rudd Labor government’s Carbon Pollution Reduction Scheme (introduced into Parliament in 2009, which was unable to pass and postponed indefinitely in 2010). Subsequently the Gillard Labor government, with support from the Australian Greens and independents, enacted the Clean Energy Future legislative package in 2011. This established a carbon pricing scheme, with an initial fixed price on carbon before the transition to a carbon trading scheme linked to international markets. Although the Clean Energy Future scheme was already influencing emission reductions,[48] it was persistently opposed by the Liberal–National coalition in opposition. In 2014, shortly after they won government in 2013, the Liberal–National Abbott government repealed the scheme, replacing it with an Emission Reduction Fund that built upon the Carbon Credits (Carbon Farming Initiative) Act 2011 (Cth) (which was part of the Clean Energy Future package).[49]

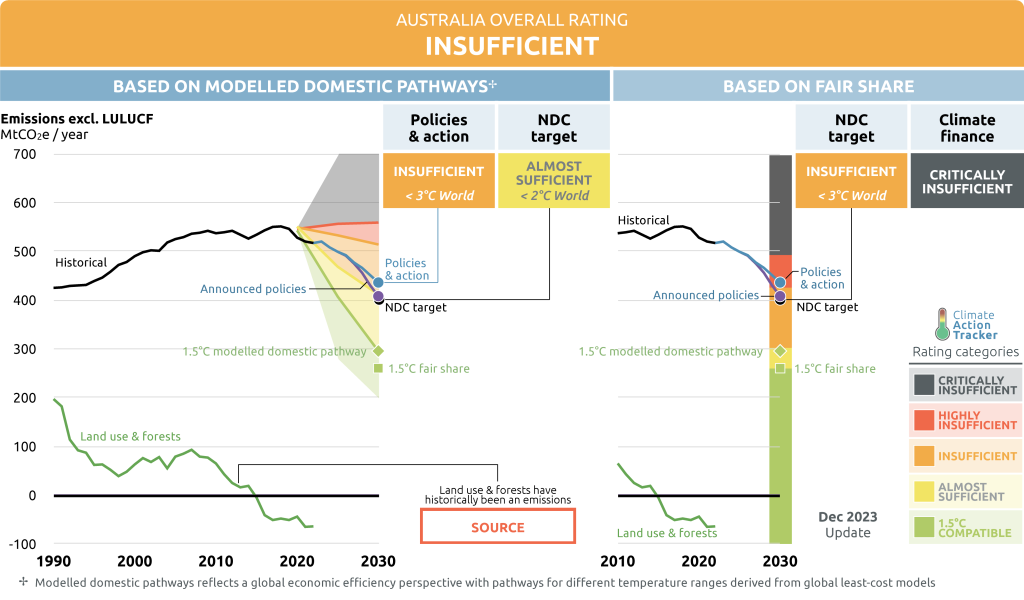

In the lead up to the Paris Agreement, Australia submitted an intended NDC to reduce emissions by 26 to 28 per cent below 2005 levels by 2030. This commitment was widely viewed to be insufficient, particularly considering that Australia is a developed country expected to take the lead in mitigating GHG emissions.[50] While most countries updated their NDCs prior to COP26 in 2021, the Australian government led by Scott Morrison simply resubmitted the unrevised, highly insufficient target. The Morrison government also released a plan to achieve net zero by 2050 which relied heavily on the future development of low-emission technology, land-use reduction and international offsets. It did not include any plan to phase out coal or reduce fossil fuel exports. In August 2022, the newly elected Albanese Labor government submitted Australia’s new NDC to the UNFCCC. It included a target to reduce GHG emissions by 43 per cent by 2030 below 2005 levels. While Climate Action Tracker described this as a significant improvement in ambition it still gave the updated NDC an overall rating of ‘insufficient’, given it was consistent with a temperature rise of 3 °C above pre-industrial levels, far exceeding what the Paris Agreement establishes as necessary to prevent dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate (see Figure 54).

Australia has sought to codify its updated international NDC at the national level through the adoption of the Climate Change Act 2022 (Cth). The Climate Change Act is the main legislation in Australia that codifies Australia’s international commitments to reduce net GHG emissions by 43 per cent below 2005 levels by 2030 and reach net zero by 2050. It also requires that a climate change statement is prepared annually and tabled in Parliament and provides that the Climate Change Authority should advise the current minister on this statement and on updated emission reduction targets. Various state and territory governments also have climate legislation that sets specific mitigation targets and promotes climate adaptation.[51]

The other key national tool governing climate action in Australia is the ‘Safeguard Mechanism’, which has been in place since 2016. The Safeguard Mechanism is enacted through the National Greenhouse and Energy Reporting Act 2007 (Cth), although key details are included in various regulations.[52] The Safeguard Mechanism requires facilities that emit more than 100,000 tonnes of CO2 equivalent (abbreviated as tCO2-e) of covered emissions[53] annually to comply with emissions limitations. Prior to 2023, the emissions limit was relatively consistent and set at business-as-usual levels. However, from 2023 onwards, facilities covered by the Safeguard Mechanism must reduce their emissions in alignment with Australia’s international commitments. Facilities that exceed their emissions limits have the option to purchase ‘carbon credits’[54] that are produced from ‘eligible activities’ focused on emission reduction or carbon sequestration.[55] However, a number of academic studies and civil society groups have highlighted environmental integrity issues with these carbon credits, and there are concerns that around 75 per cent of the credits do not represent new, additional or real emission reductions.[56]

Outside of specific climate laws and policies, Australia’s main environmental protection law — the Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Cth) (EPBC Act) — does not explicitly address the climate impacts of GHG-intensive projects.[57] Various independent reviews and reports on the EPBC Act have called for the inclusion of a ‘climate trigger’.[58] However, to date no such trigger has been included in the legislation. That said, as of 2023 and at the time of writing, there were two private member bills before Parliament that sought to modify the EPBC Act to require the consideration of GHG emissions and climate change considerations.[59] There have also been various attempts through litigation to ask courts to interpret the decision-making provisions of the EPBC Act to require the consideration of GHG emissions, including in Wildlife Preservation Society of Queensland Proserpine/Whitsunday Branch v Minister for the Environment and Heritage (‘Wildlife Whitsunday Ccase’), Australian Conservation Foundation (ACF) v Minister for the Environment (‘Carmichael Coal Mine’ Ccase’) and Environment Council of Central Queensland Inc v Minister for the Environment and Water (No 2) (‘Living Wonder’ Ccase’). These cases have (to date) been unsuccessful.

More broadly, there has also been growing use of the courts to try to achieve climate regulatory outcomes.[60] ‘Climate litigation’ has been defined as “‘cases that raise material issues of law or fact relating to climate change mitigation, adaptation, or the science of climate change … brought before a range of administrative, judicial, and other adjudicatory bodies”’.[61] There has been a drastic growth in climate litigation over the past decade globally.[62] Over recent years, there has been a global and domestic surge in climate change related litigation. As of July 2023, some 2,180 climate change related court cases have commenced or concluded globally, spanning courts in 65 domestic jurisdictions and international and regional courts, tribunals and quasi-judiciary bodies.[63] A small but growing subset of these cases strategically seek to push states to enhance and implement state mitigation or adaptation commitments.[64]

Australia is, after the United States, the jurisdiction that has seen the most climate litigation actions, with over 134 cases filed. While the ‘first generation’ of climate litigation in Australia primarily used administrative law to challenge governmental decision-making, especially around coal-fired power stations and coal mines, the ‘second generation’ of climate litigation has innovatively deployed a range of laws — including company, trust, constitutional, tort, human rights laws and others — to promote an “‘accountability model whereby legal interventions are designed to hold governments and corporations directly to account for the climate change implications of their activities”’.[65] Various arguments developed in climate litigation will be discussed in chapters throughout this book.

Key Questions

- Why do you think Australia has been such a ‘laggard’ on climate action? What would it take to turn Australia from a laggard to a leader?

- Do you think Australia’s commitment to reduce GHG emissions by 43 per cent below 2005 levels by 2030 is adequate or equitable? Why/why not?

- Do you think existing Australian laws and policies will effectively achieve the policy objectives to reduce GHG emissions by 43 per cent below 2005 levels by 2030? Why/why not?

- What additional or changed legal frameworks do you think might be needed?

- United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (adopted 9 May 1992, entered into force 24 March 1994) 1771 UNTS 107 (UNFCCC). ↵

- Kyoto Protocol to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (adopted on 11 December 1997, entered into force on 16 February 2005) 2303 UNTS 162 (Kyoto Protocol). ↵

- Paris Agreement to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change, (adopted 12 December 2015, entered into force 4 November 2016) Doc. FCCC/CP/2015/10/Add.1 (Paris Agreement). ↵

- Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment and the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law, ‘Climate Change Laws of the World’ <https://climate-laws.org>. ↵

- UNFCCC (n 1) preambular para 1. ↵

- Ibid Article 3.1. ↵

- Ibid Article 3.2. ↵

- Ibid Article 3.3. ↵

- Ibid Article 4.1. ↵

- Ibid Article 4.2. ↵

- Ibid Article 4.3. ↵

- Kyoto Protocol (n 2) Article 3.1. ↵

- Ibid Article 17. ↵

- Ibid Article 6. ↵

- Ibid Article 12. ↵

- See generally, Alex Y. Lo and Ren Cong, ‘Emission Reduction Targets and Outcomes of the Clear Development Mechanism (2005–2020)’ (2022) 1(8) PLOS Climate e0000046. ↵

- UNFCCC, Decision 1/CP.13, ‘Bali Action Plan’, UN Doc. FCCC/CP/2007/6/Add.1 (14 March 2008). ↵

- UNFCCC, Decision 1/CP. 15, ‘Copenhagen Accord’, UN Doc. FCCC/CP/2009/11/Add.1 (30 March 2010). ↵

- UNFCCC, Decision 1/CP.17, ‘Durban Platform’, UN Doc. FCCC/CP/2011/9/Add.1 (15 March 2012). ↵

- Julia Dehm, ‘Reflections on Paris: Thoughts towards a critical approach to climate law’ (2018) Revue Québécoise de Droit International 61–91. ↵

- Paris Agreement (n 3) Article 2.1(a). ↵

- Ibid Article 2.1(b). ↵

- Ibid Article 2.1(c). ↵

- Ibid Article 4. 2. ↵

- Ibid Article 4.9. ↵

- Ibid Article 4.3. ↵

- Ibid Article 14. ↵

- UNFCCC, Draft decision/CMA.5, ‘First Global Stocktake’, UN Doc. FCCC/PA/CMA/2023/L.17 (13 December 2023). ↵

- Paris Agreement (n 3) Article 7. ↵

- Ibid Article 8(1). ↵

- Ibid Articles 9, 10, and 11. ↵

- World Meteorological Organization, Proceedings of the World Conference on the Changing Atmosphere: Implications for Global Security (27–30 June 1988) (‘Toronto Conference on the Changing Atmosphere’). ↵

- UNFCCC, Decision 1/CMA.3, ‘Glasgow Climate Pact’, FCC/PA/CMA/2021/l.16 (2021). ↵

- Ibid para 36. ↵

- UNFCCC, Decision -/CMA.5, ‘First Global Stocktake’, FCCC/PA/CMA/2023/L.17 (13 December 2023). ↵

- IPCC, Regional Fact Sheet — Australasia, Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Cambridge University Press, 2021). ↵

- Kate Crowley, ‘Fighting the Future: The Politics of Climate Policy Failure in Australia (2015–2020)’ (2021) 12(5) WIREs Climate Change e75; Tek Maraseni and Kathryn Reardon-Smith, ‘Meeting National Emissions Reduction Obligations: A Case Study of Australia’ (2019) 12(3) Energies 438. ↵

- Climate Change Authority, Prospering in a Low-Emissions World: An updated climate policy toolkit for Australia (Australian Government, March 2020); Ross Garnaut, Superpower: Australia's Low-Carbon Opportunity (La Trobe University Press, 2019). ↵

- Beyond Zero Emissions, Laggard to Leader: How Australia can lead the world to zero carbon prosperity (June 2012). ↵

- Ember, G20 Per Capita Coal Power Emissions 2023: Australia and South Korea retain their positions as G20's top polluters (Report, 5 September 2023). ↵

- Australian Government, ‘Coal’, Geoscience Australia (accessed 13 December 2023) <https://www.ga.gov.au/digital-publication/aecr2023/coal#:~:text=Australia exported 10,324 PJ of,the Environment and Water 2022c)>. ↵

- Graham Readfearn, ‘Australian coal burnt overseas creates nearly twice the nation’s domestic emissions’, The Guardian (2 June 2021) <https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2021/jun/02/australian-coal-burnt-overseas-creates-nearly-twice-the-nations-domestic-emissions>. ↵

- Australian Government, ‘Gas’, Geoscience Australia (accessed 13 December 2023) <https://www.ga.gov.au/digital-publication/aecr2022/gas>. ↵

- Stockholm Environment Institute, Climate Analytics, E3G, International Institute for Sustainable Development, and United Nations Environment Programme, Production Gap Report 2023: Phasing down or phasing up? Top fossil fuel producers plan even more extraction despite climate promises (SEI, Climate Analytics, E3G, IISD, and UNEP report, 2023) 55 (‘Production Gap Report 2023’). ↵

- Guy Pearce, Quarry Vision: Coal, Climate Change and the End of the Resource Boom (Quarterly Essay, 2009). ↵

- Adam Lucas, ‘Investigating Networks of Corporate Influence on Government Decision-Making: The Case of Australia’s Climate Change and Energy Policies’ (2021) 81 Energy Research & Social Science 102271. ↵

- Production Gap Report 2023 (n 44) 54. ↵

- Kate Crowley, ‘Up and Down with Climate Politics 2013–2016: The Repeal of Carbon Pricing in Australia’ (2017) 8(3) WIREs Climate Change e458; Jacqueline Peel, ‘The Australian Carbon Pricing Mechanism: Promise and Pitfalls on the Pathway to a Clean Energy Future’ (2014) 15(1) Minnesota Journal of Law, Science & Technology 429. ↵

- For the history see Tim Baxter, George Gilligan, and Cosima Hay McRae, ‘Australian Climate Change Regulation and Political Math’ (2018) 20(7) University of Melbourne Legal Studies Research Paper No. 798. ↵

- Climate Action Tracker, ‘Australia’ <https://climateactiontracker.org/countries/australia/targets/>. ↵

- Wildlife Preservation Society of Queensland Proserpine/Whitsunday Branch Inc v Minister for the Environment & Heritage [2006] FCA 736; Australian Conservation Foundation (ACF) v Minister for the Environment [2017] FCAFC 134; Environment Council of Central Queensland Inc v Minister for the Environment and Water (No 2) [2023] FCA 1208. ↵

- National Greenhouse and Energy Reporting (Safeguard Mechanism) Rule 2015 (Safeguard Rule), alongside the Carbon Credits (Carbon Farming Initiative) Rule 2015, and the Australian National Registry of Emissions Units Regulations 2011. ↵

- Safeguard Rule (n 52). Covered emissions are defined in section 22XL as “‘scope 1 emissions of one or more greenhouse gases, other than emissions of a kind specified in the safeguard rules”’. There are also a number of exceptions including: legacy emissions from the operation of a landfill facility (that is, emissions from waste deposited at the landfill before 1 July 2016); emissions which occur in the Greater Sunrise special regime area; emissions from the operation of a grid-connected electricity generator in a year covered by the sectoral baseline; emissions not covered under the National Greenhouse and Energy Reporting (Measurement) Determination 2008. ↵

- These are called Australian Carbon Credits Units (ACCUs), see Carbon Credits (Carbon Farming Initiative) Act 2011 (Cth). ↵

- Carbon Credits (Carbon Farming Initiative) Act 2011 (Cth). ↵

- Polly Hemming, Richie Merzian, and Annica Schoo, Questionable Integrity: Non-additionality in the Emission Reduction Fund’s Avoided Deforestation Method (The Australia Institute, 2021); Paul J. Burke, ‘Undermined by Adverse Selection: Australia’s Direct Action Abatement Subsidies’ (2016) 35(3) Economic Papers 216. ↵

- Jacqueline Peel, Legal opinion: Gaps in the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act and other Federal Laws for Protection of the Climate (Report for the Climate Council, 2023). ↵

- See especially, Australian Government Department of the Environment, Water, Heritage and the Arts, Allan Hawke, The Australian Environment Act: Report of the Independent Review of the Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Final report, October 2009) ↵

- Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Amendment (Climate Trigger) Bill 2022 [No. 2]; Climate Change Amendment (Duty of Care and Intergenerational Climate Equity) Bill 2023. ↵

- Jacqueline Peel and Hari M. Osofsky, Climate Change Litigation: Regulatory Pathways to Cleaner Energy (Cambridge University Press, 2015). ↵

- United Nations Environment Programme, Global Climate Litigation Report: 2020 Status Review (UNEP, 2020). ↵

- United Nations Environment Programme, Global Climate Litigation Report: 2023 Status Review (UNEP, 2023). ↵

- For an overview of the main types of climate change cases used to strategically influence policy outcomes and the behaviour of relevant actors, see Joana Setzer and Catherine Higham, Global Trends in Climate Change Litigation: 2023 Snapshot (Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment and Centre for Climate Change Economics and Policy, London School of Economics and Political Science, 2023) 19–25. ↵

- Ben Batros & Tessa Khan, Thinking Strategically About Climate Litigation, Open Global Rights (June 28, 2020) <https://www.openglobalrights.org/thinking-strategically-about-climate-litigation/>. ↵

- Jacqueline Peel, Hari Osofsky, and Anita Foerster, ‘Shaping the “Next generation” of Climate Change Litigation in Australia’ (2017) 41 Melbourne University Law Review 793. ↵

Any process, activity or mechanism which removes a greenhouse gas … from the atmosphere (IPCC, Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change).

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) is an intergovernmental organisation of 38 member countries, including Australia, that collaborates with over 100 nations to develop evidence-based analysis and international standards. Funded by its members, the OECD plays a key role in shaping public policy and informing global debates on economic and social governance.[1]

[1] Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, About the OECD (Web Page) https://www.oecd.org/about/.

A human intervention to reduce emissions or enhance the sinks of greenhouse gases (IPCC, Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change).

The process of adjustment to actual or expected climate and its effects (IPCC, Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability).

There are many definitions of climate justice. The definition by the Climate Justice Global Alliance states that ‘climate justice advocates for equitable solutions that prioritize the needs of those who are most affected by climate change, strive to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and ensure that the burdens and benefits of climate action are distributed fairly, taking into account historical and systemic inequalities.’ Climate justice has various aspects:

- Distributive justice: paying attention to inequalities in the causes, burdens of addressing and experience of impacts.

- Procedural justice: ensuring participatory, accessible, fair and inclusive processes to address climate change.

- Recognition justice: centring voices of those who have historically been marginalised, such as First Nations in Australia.

- Reparative or corrective justice: considering what actions are necessary to redress and repair harms caused

The negative impacts of climate change that occur despite, or in the absence of, mitigation and adaptation.

‘Sustainable development is development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs… In its broadest sense, the strategy for sustainable development aims to promote harmony among human beings and between humanity and nature.’[1]

[1] Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development: Our Common Future, U.N. Doc. A/42/427, Annex (20 March 1987) 81. The Brundtland Report definition of ‘sustainable development’ was adopted by the United Nations General Assembly: United Nations General Assembly, Report of the World Commission on Environment and Development (NRES/42/187) 11 December 1987.

An energy source formed in the Earth’s crust from decayed organic material. The common fossil fuels are petroleum, coal, and natural gas.[1]

[1] U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), Glossary <https://www.eia.gov/tools/glossary/index.php?id=Fossil%20fuel#:~:text=Fossil%20fuel%3A%20An%20energy%20source,%2C%20coal%2C%20and%20natural%20gas>.

Climate wars in Australia refers to the acute political contestation and polarisation in Australia in relation to the necessity and level of state response to climate action.

Cases where climate change is a central issue in the dispute, climate change is raised as a peripheral issue, climate change is one motivation behind the case, or where the case has implications for mitigation or adaptation (Jacqueline Peel and Hari Osofsky, Climate Change Litigation: Regulatory Pathways to Cleaner Energy, Cambridge University Press, 2015, p. 8).

Jurisdiction refers to the scope of a court’s authority to decide matters. It comes from the Latin ‘juris’ (the law) and ‘dicto’ (to say or declare).