2. Climate Science

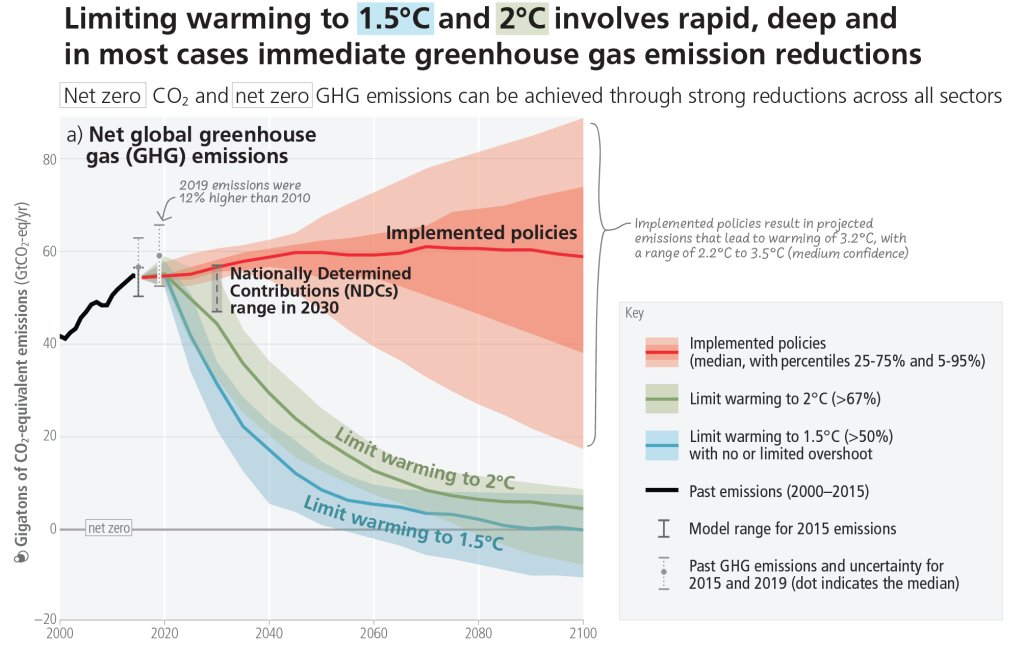

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) is the main international scientific body on climate change and issues periodic assessment reports.[1] The most recent IPCC Assessment Report concludes that it is ‘unequivocal’ that GHG-emitting human activities are the primary cause of global warming since the mid-20th century.[2] The primary emissions-intensive activities driving global warming are first, fossil-fuel combustion and industrial activities, and second, the clearing of land for agriculture, industry and other human activities.[3] These activities contribute to the emission of four main GHGs (carbon dioxide, nitrous oxide, methane and halocarbons). GHG emissions trap heat in the atmosphere, leading to global warming and the consequential impacts of climate change. Concentrations of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere are unprecedented in comparison with the past 2 million years, and atmospheric concentrations of methane and nitrous oxide are higher than any time in the past 800,000 years.[4] In this context, global temperatures have already risen by approximately 1.2°C since the pre-industrial era.[5] Moreover, states’ GHG emission reduction commitments set the world on a course for a global temperature rise of an estimated 2.9°C by 2100.[6]

Human-induced climate change is associated with the increased occurrence and severity of extreme events, such as heatwaves and floods, as well as slow-onset events like temperature rise and ocean warming. These extreme and slow-onset events are already causing widespread but unevenly distributed adverse impacts and related losses and damages to natural and human systems, such as losses of biodiversity and ecosystem services; food and water insecurity; harmful outcomes for human health; damage to cities, infrastructure and settlements; and losses of territory, cultural heritage and Indigenous or local knowledges. Those that have contributed least to historic and current GHG emissions often face the first and worst impacts of climate change.[7] Conversely, those that have contributed most to the causes of climate change, and thus benefited most from GHG-intensive activities, now possess more resources to respond and adapt to the impacts of climate change.

Australia is in a unique position with respect to climate change, being highly vulnerable to the impacts of climate change while also disproportionally contributing to atmospheric GHG emissions relative to its population size. In Australia, temperatures have risen by an estimated 1.47°C since 1910.[8] This temperature rise has contributed to in an increased risk of bushfires in Australia.[9] Simultaneously, surrounding sea levels are rising at a rate faster than the global average, resulting in coastal erosion and flooding throughout Australia’s coastal regions and low-lying islands.[10] The degradation of Australia’s coral reefs and marine biodiversity similarly illustrates the adverse impacts of climate change in our region. Australia’s coral reefs provide critical habitats for marine biodiversity and support ecosystem services in the coastal environment, such as fisheries productivity, drawing carbon from the atmosphere (‘carbon sequestration’) and helping to reduce marine pollution.[11] The degradation of Australia’s marine environment therefore has implications for economic and food security[12] and the capacity for Australia to achieve and uphold emission limitation and reduction standards,[13] as well as the continued habitability of surrounding low-lying islands.[14]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Global Warming of 1.5°C: An IPCC Special Report on the Impacts of Global Warming of 1.5°C Above Pre-Industrial Levels and Related Global Greenhouse Gas Emission Pathways, in the Context of Strengthening the Global Response to the Threat of Climate Change, Sustainable Development, and Efforts to Eradicate Poverty (Cambridge University Press, 2019); Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, The Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate: A Special Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Cambridge University Press, 2019) Summary for Policy Makers (‘2019 IPCC Special Report’); Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Cambridge University Press, 2021) (‘AR6 WGI’); Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability: Working Group II Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Cambridge University Press, 2022) (‘AR6 WGII’); Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Cambridge University Press, 2022) (‘AR6 WGIII’). ↵

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, ‘Summary for Policymakers’ in Climate Change 2023: Synthesis Report. Contribution of Working Groups I, II and III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Cambridge University Press, 2023) A.1 (‘IPCC Synthesis of the Sixth Assessment Report’). ↵

- Ibid A.1.4. ↵

- Ibid A.1.3. ↵

- World Meteorological Organization, Provisional State of the Global Climate 2023 (WMO Annual Report, 30 November 2023). ↵

- According to the United Nations Environment Programme, current policies and unconditional nationally determined contributions are projected to result in global warming of 2.9°C (with a range of 2.0 to 3.7). If all conditional nationally determined contributions are implemented, temperature rise may peak at 2.5°C. If all net-zero pledges are also fulfilled, temperature rise may be limited to 2.0°C. See United Nations Environment Programme, Emission Gap Report 2023: Broken Record — Temperatures hit new highs, yet world fails to cut emissions (again) (UNEP Report, 2023) Table 4.4. ↵

- IPCC Synthesis of the Sixth Assessment Report (n 2) A.2. ↵

- Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation and the Bureau of Meteorology, State of the Climate 2022 (CSIRO Report, 2022) 2. ↵

- Josep G. Canadell, ‘Multi-decadal Increase of Forest Burned Area in Australia is Linked to Climate Change’ (2021) 12 Nature Communications 6921. ↵

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, ‘Australasia’ in Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability: Working Group II Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Cambridge University Press, 2022), Table 11.1, Table Box 11.6.2. ↵

- Aaron M. Eger et al, ‘The Value of Ecosystem Services in Global Marine Kelp Forests’ (2023) 14(2841) Nature Communications 1; Aaron M. Eger at el, ‘Quantifying the Ecosystem Services of the Great Southern Reef’ (Final Report, National Environmental Science Program, University of New South Wales, November 2022). ↵

- Economic losses associated with climate change in Australia are predicted to amount to $5 trillion by 2100: Tom Kompas, Ellen Witte, and Marcia Keegan, Australia’s Clean Energy Future: Costs and Benefits (Melbourne Sustainable Society Institute Issues Paper 12, The University of Melbourne, 2023). ↵

- Micheli Duarte de Paula Costa et al, ‘Current and Future Carbon Stocks in Coastal Wetlands within the Great Barrier Reef catchments’ (2021) 27(14) Global Change Biology 3257; Linwood Pendleton et al, ‘The Great Barrier Reef: Vulnerabilities and solutions in the face of ocean acidification’ (2019) 31 Regional Studies in Marine Science 100729. ↵

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, ‘Sea Level Rise and Implications for Low-Lying Islands, Coasts and Communities’ in The Ocean and Cryosphere in a Changing Climate: A Special Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (Cambridge University Press, 2019). ↵

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) is an intergovernmental body of the United Nations that publish interim reports advancing scientific consensus about climate change caused by human activities.

The negative impacts of climate change that occur despite, or in the absence of, mitigation and adaptation.