Climate Change and Constitutional Law

Costa Avgoustinos and Harry Hobbs[1]

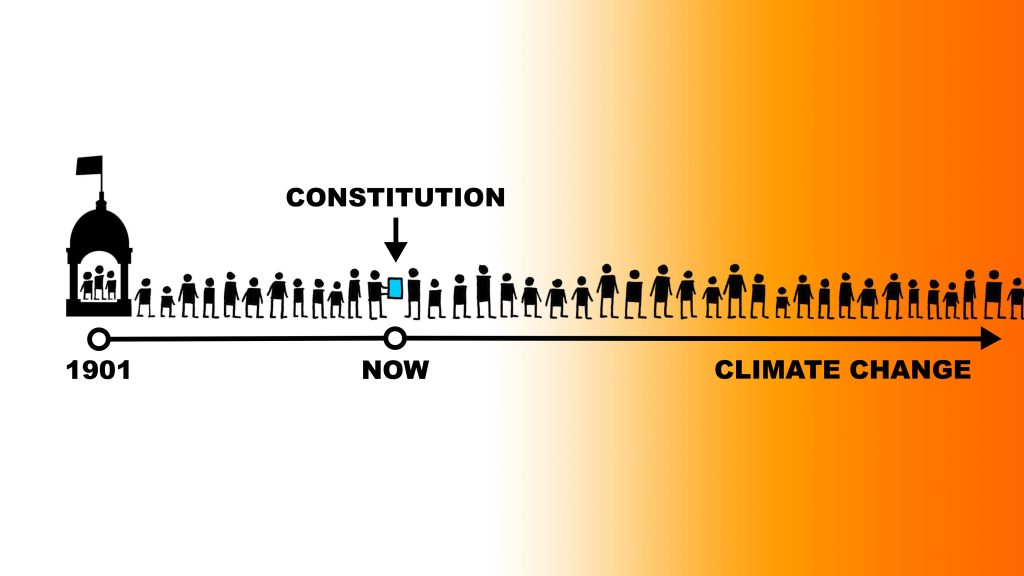

The Commonwealth Constitution (‘Constitution’) is the foundational law in Australia. It establishes the Commonwealth of Australia as a federation governed under a parliamentary system of representative and responsible government. It distributes and regulates powers both horizontally — across the federal parliament, the executive and the judiciary — and vertically between the states and the Commonwealth. All laws passed by a parliament or actions undertaken by an executive must be consistent with the Constitution as the supreme law in this country. This means that the instrument establishes the legal and political system within which climate change must be addressed in Australia.

The Constitution does not mention the environment or climate change. In part, this is because the document was drafted in the 1890s, before modern environmental concerns existed. It is also due to the framers’ preference for a model of political constitutionalism for rights-based adjudication. Political constitutionalism aims to hold government accountable through political institutions and processes. It prioritises the creation of a robust democratic system in which government wrongdoing may be curbed through political means, such as public debate and parliamentary scrutiny. In contrast, solely legal constitutions look primarily to the courts to control the executive by placing detailed limits on government power.

The Constitution is the primary source of constitutional law, but it sits alongside other constitutional sources. These include constitutional conventions, state constitutions, key legal instruments issued on the path to Australian independence from the United Kingdom, such as the Australia Act 1986, and decisions of the High Court of Australia. As we will see, even though the Constitution does not mention the environment, important decisions by the High Court continue to shape legal and political responses to climate change.

The result is the Constitution empowers the Commonwealth and states to collectively address the climate crisis largely as they see fit. The primary constitutional tools available to people dissatisfied with climate laws and policies are the various democratic processes set up by the Constitution to keep governments accountable, alongside some forms of judicial review.

This chapter examines the strengths and weaknesses of this arrangement. We begin, in part 1, by outlining how the Constitution divides control over climate change between the Commonwealth and states (and the High Court’s role in resolving tensions between the two). In part 2, we explore the few constitutional limitations that restrain governmental decision-making in this policy area. Part 3 looks to the future. It offers a critique of how climate change has been handled within the largely political constitutionalist framework, then considers two possible avenues for improvement — constitutional amendment and constitutional implications.

KEY QUESTIONS

- How do the Commonwealth and states share power over climate matters?

- In what ways does the Constitution hinder and facilitate climate action?

- How has the Constitution been utilised to address climate change?

- How may it be utilised in future?

- Does climate action require constitutional change?

CHAPTER OUTLINE

1. Government Powers to Address Climate Change

2. Constitutional Limitations to Promote Climate Action

2.1. The Absence of Environmental Protection Provisions

2.2. Interstate Trade (Section 92)

2.3. Implied Freedom of Political Communication

2.4. Excise Duties (Section 90)

2.5. Acquiring Property (Section 51(xxxi))

3. Future Trajectories of Australian Constitutional Law

- With special thanks to Nicole Rogers for her contributions to this chapter. ↵

An approach to drafting a constitution that emphasises political institutions and processes to hold governments accountable. The expectation is that political means, such as public debate and parliamentary scrutiny, will effectively weed out government wrongdoing. This contrasts with constitutions written in a legal constitutionalist model. Such constitutions typically include more detailed limits on government power to be enforced by courts.