10 Te Whakaoreore Aromatawai Hāpai ki te Hapori:

He Awa Whiria approach to assessing change in communities

Dr. Cristy Trewartha; Keelan Ransfield; Moerangi Falaoa-Rakaupai; Mathew Mullany; Anne McKenzie; Dr. Zach Penman; and Dr. Lucy Langston

![]()

E Tū Whānau

E Tū Whānau is a movement for positive change developed by Māori for Māori.[1] It is founded on tikanga and Māori values that uplift, strengthen and protect whānau.

E Tū Whānau is a call to action to whānau to stand together to achieve the vision that:

Whānau are strong, safe and prosperous – active within their community, living with a clear sense of identity and cultural integrity, and with control over their destiny. Te mana kaha o te whānau! (E Tū Whānau, 2020, p 5)

E Tū Whānau operates as a Māori-Crown partnership, which is designed and led by Māori, supported by government, and situated in the Ministry of Social Development. E Tū Whānau aims to prevent violence by working with whānau and communities, in a culturally safe and responsive way, to create change from within. It does this by supporting whānau and community initiatives that shift social norms, encourage leadership, and grow capability within communities. E Tū Whānau takes a strengths-based approach to primary prevention, working to increase protective factors and reduce risk factors for violence within whānau.[2]

![]()

Introduction

Understanding whether work to make change in communities is having an impact is tricky. There are very few tools available to measure community mobilisation and change, and fewer still that align with te ao Māori. Community mobilisation is a primary prevention strategy[3] that is recommended in the emerging evidence to prevent violence against women and children (Contreras-Urbina et al., 2016; Michau, 2007; PwC, 2016; PwC, Our Watch and VicHealth, 2015). Community mobilisation has been adopted as a key prevention strategy in Aotearoa New Zealand (Hann and Trewartha, 2015). While international evidence of the effectiveness of community mobilisation is promising (Abramsky et al., 2014), there is little evidence relevant to our experiences here in New Zealand.

The challenge for the E Tū Whānau team was to develop the ability to assess the impact of the work in communities and change over time, in a way that was acceptable to both communities and central government. To enable cross-culturally valid assessment of impact and change over time, E Tū Whānau worked with a Pākehā community-measurement specialist, as well as Māori practitioners from the communities they support, to co-create an innovative tool to measure community mobilisation. Named Te Whakaoreore Aromatawai Hāpai ki te Hapori – The Community Mobilisation Assessment Tool, the tool is a dialogue-based community self-assessment. It is an innovative approach to measuring change, which operationalises He Awa Whiria, the braided rivers approach (Macfarlane et al., 2015).

The assessment tool supports E Tū Whānau and communities to understand the impact of their efforts to increase whānau wellbeing and challenge violence within whānau, to focus efforts for greater impact and to track change in communities over time.

He Awa Whiria was applied to the process that the authors, as Māori and Pākehā practitioners, took to co-create the tool. He Awa Whiria was a natural fit for E Tū Whānau, which has from its inception been informed by a braided approach, and elevates kaupapa Māori ways of knowing and doing. He Awa Whiria supports Māori and non-Māori to interact in mutual respect for each other’s ways of knowing.

While the institutional structures within which the tool was developed are in a historic moment of openness to change, they remain largely resistant to kaupapa Māori methods. The tool, and the wider E Tū Whānau research and evaluation strategy, are designed to elevate kaupapa Māori and to challenge the implicit hierarchy of Western over Māori ways of knowing.

He Awa Whiria in action

To understand the significance of this He Awa Whiria-informed assessment tool, it is important to acknowledge the journey of E Tū Whānau. E Tū Whānau emerged from a national summit of Māori leaders, held in April 2008, which was opened by the Māori King Tuheitia and hosted by the Waikato-Tainui tribal confederation at Hopuhopu Marae. This summit was a historic opportunity for Māori to address (and ultimately eliminate) all forms of violence within whānau. The consensus was that a fresh approach was needed based on Māori ways of doing things, led by Māori, and focused on strengths and success within a context of whānau ora (wellbeing). More than 30 subsequent hui held across the country endorsed this approach, and suggested the principles and recommendations for action.

The summit, hui and discussion provided a clear mandate and direction. The voice of Māori was embedded in the E Tū Whānau kaupapa and provided the foundation for all of the work that was to come. Those involved at this critical early stage, including the E Tū Whānau Māori Reference Group that later guided the development of E Tū Whānau, looked nationally and internationally for solutions and evidence to shape the nature of investment and activity. However, it became clear that there was very little that was relevant to Māori in New Zealand. E Tū Whānau recognised that whānau, hapū, iwi and communities were the experts on their own lives, and that the solutions lay within te ao Māori. Concurrently, evidence in the global literature on primary prevention of violence was developing on the importance of community mobilisation that built community leadership and self-determination (Michau, 2007).

The He Awa Whiria metaphor, although articulated later, was always, in essence, a part of E Tū Whānau. The approach of E Tū Whānau is founded on the principles that Māori know what works best for Māori and that the primary role of central government is to support solutions designed, driven and delivered by Māori. Implicit in this approach is the acknowledgement that pooling the strengths of both Māori and government expertise will offer the best results for whānau, hapū, iwi and Māori communities. Today, this approach is seen as transformational by those working in government. At the time, this approach was unprecedented.

He Awa Whiria informs our Mahere Rautaki: Rangahau me te Arotake (research and evaluation plan)

E Tū Whānau is based on centuries of mātauranga Māori, and on decades of emerging kaupapa Māori and Indigenous research and evidence. E Tū Whānau has been funding and doing research and evaluation to help build the knowledge and evidence base for primary prevention generally, and kaupapa Māori specifically. Data sets are being collected and analysed to interpret and explain what matters, what works and, conversely, what doesn’t work, to mobilise communities and achieve wellbeing. This includes a focus on: growing youth leadership; restoring the traditional identities, balance and complementarity of Māori men and women; strengthening the protective factors that keep whānau safe and support wellbeing; and mitigating risk factors to prevent violence.

The challenge in developing the research and evaluation plan was to draw on that evidence base to develop a kaupapa Māori and cross-culturally valid research, evaluation, monitoring and learning system to meet the short-, medium- and long-term knowledge needs of E Tū Whānau. There is an urgent need for New Zealand to produce rich and robust context-specific knowledge and evidence relevant to Māori. This imperative has shaped the research and evaluation plan, which also enacts He Awa Whiria.

There are several tensions between Western and Māori approaches to research and evaluation that need to be negotiated. One example is the Western focus on externally led, independent research and evaluations, which are often regarded as superior to internally led research and evaluation, for the purpose of public transparency and accountability. However, for the purposes of continuous learning and improvement and fit with te ao Māori, internally led research and evaluation has many advantages. For example, internal researchers have stronger relationships and share tacit understandings with colleagues and participants, which means they can access information that might not be shared with outsiders, and they have the time and resources to invest in properly socialising and embedding new knowledge and evidence.

In a Māori context, the Western epistemic privileging of the ‘external- observer’ perspective over the ‘internal-participant’ perspective is reversed, with insiders related to the research participants thought to be in a stronger position to perceive and analyse efforts to make change. Within E Tū Whānau, colleagues have the experience, practical knowledge and mātauranga Māori subject-matter expertise that can complement the strengths of external evaluators. So, the E Tū Whānau team looks at the full spectrum of options – from internal to co-created to external research and evaluation – to decide what the most ethical, efficient and effective option is for any given knowledge requirement.

He Awa Whiria approach to measuring community mobilisation and change

The decision to utilise He Awa Whiria in the development of the assessment tool evolved from an initial He Awa Whiri-informed analysis of E Tū Whānau in relation to Western evidence on community mobilisation (Trewartha, 2020a). This work showed that measuring change in communities is an area with limited evidence (Trewartha, 2020b), and that there were no tools, to the authors’ knowledge, that had been developed by, for and with Māori.

E Tū Whānau wanted to learn what change was happening in the communities they were working with, both to support development of the programme of work and the communities and whānau navigating their journeys of change; and as a government-funded initiative, to fulfil reporting obligations for public transparency and accountability. There was little available evidence on measuring change from a te ao Māori perspective, so the process started by learning from the Western evidence on community mobilisation (Trewartha, 2020b). Lippman et al. (2013) and Trewartha (2020b) have identified six domains, or essential elements, of community mobilisation from the academic Western evidence. The domains are: leadership, organisation, participation, shared concern, critical consciousness and social cohesion. This led to an analysis – guided by He Awa Whiria – of the kaupapa Māori evidence E Tū Whānau had developed and the Western evidence on community mobilisation.

This analysis (Trewartha, 2020a) showed a high level of alignment between the two evidence streams, but also some important differences. A key difference was the grounding of E Tū Whānau in te ao Māori, and the use of tikanga Māori, cultural knowledge, values and spirituality to create safe spaces for transformative dialogue. Another difference was the focus of E Tū Whānau beyond stopping the problem of violence within whānau to fostering whānau wellbeing, which was not a specific focusin the Western literature. Finally, the focus of the Western evidence was on what to do to mobilise communities for change (for example, develop community leaders), whereas the kaupapa Māori evidence provided guidance on how to mobilise communities (for example, use tikanga Māori to build relationships first). This He Awa Whiria analysis established a foundation on which the assessment tool was developed.

He Awa Whiria co-creation process

Guided by He Awa Whiria, the authors embraced what was known from the Western evidence, while elevating knowledge about methods of engagement and understanding of change from te ao Māori. The aim was to develop an assessment tool that felt natural within a Māori context, one that created a positive experience of research and assessment for whānau and communities, while meeting the evidence and accountability needs of central government.

He Awa Whiria was a practical model to guide the co-creation process – involving Māori and Pākehā – that supported a robust development process of braiding knowledge from Western literature and mātauranga Māori. Initially, the more established evidence of the Western stream was a stronger influence in tool development. However, through the He Awa Whiria development journey, the kaupapa Māori stream was strengthened and the final result was a tool that is well aligned to kaupapa Māori. In the process, the tool evolved from an individualised Western approach (a quantitative, self-completion questionnaire) to a collective approach – a dialogue-based, community self-assessment tool.

The He Awa Whiria approach was also used with the peer-review process. While most peer reviewers were Māori academics, a Pākehā academic was also included, who had experience of collective measurement of wellbeing in a range of contexts, including with Indigenous communities.

The tool-development process and initial survey tool were supported by peer review and testing with Māori practitioners and researchers. Both groups made it clear that whānau and communities did not want to fill in long questionnaires. However, they said the content of the survey was really engaging, and the authors observed how quickly discussion started when practitioners were presented with the initial survey content.

From this point, knowledge about what works for Māori supported the evolution of the tool towards preferred Māori collective processes, using dialogue that led to learning and making decisions as a community, and self-assessment that demonstrates self-determination for Māori communities.

This evolution demonstrated the negotiation of a key tension between te ao Māori and Western worldviews – the emphasis on the collective or on the individual. While a Western, individualised survey tool provides data that can be statistically analysed, and is seen as a valid and robust approach to assessment, this approach has little meaning within te ao Māori. Moving towards collective self-assessment provided a good fit with te ao Māori, but this is largely without precedent in government spaces. Acceptance of this innovative approach within government requires an openness to new ways of understanding what evidence is meaningful, and to whom, and to embracing research processes that work for Māori and communities.

The co-creation process involved considerable time workshopping and exploring the language used, and multiple meanings of words, from both Māori and Pākehā perspectives. This was a crucial part of the development process, as it highlighted differences in Western and Māori worldviews and ensured intentional and well-informed use of English and te reo Māori. Experts and practitioners also gave important feedback on the language used, to ensure the tool was strengths-based and welcomed whānau engagement.

For this tool, it was important that only a small amount of te reo Māori was used; this ensured it was accessible to whānau and communities with limited te reo Māori. Loss of language is one of the many significant impacts of colonisation. Using accessible language was part of ensuring that participating in an assessment was a mana-enhancing experience, and not one that increased whakamā (shame) or pōuri (sadness) about not speaking te reo Māori.

Outcome of our work using He Awa Whiria

He Awa Whiria supported a robust development process of braiding what was known in the Western literature and mātauranga Māori. The outcome of the process was a dialogue-based community self-assessment tool.

The assessment tool is designed to be implemented within a wānanga:

A wānanga is characterised by teaching and research that maintains, advances and disseminates knowledge and develops intellectual independence, and assists the application of knowledge regarding ahuatanga Māori (Māori tradition) according to tikanga Māori (Māori custom).[4]

Use of the tool within a wānanga setting is designed to make sure that whānau are safe to share their thoughts and stories with all in attendance. The customs and protocols of the wānanga support this.

Application of the assessment tool involves facilitated discussion on eight topics:[5]

• Increasing leadership in whānau, hapū, iwi and communities

• Strengthening connection to culture and identity

• Increasing community knowledge, skills, capability and confidence

• Strengthening relationships within and across whānau, families and the wider community

• Increasing readiness to engage in a journey of healing and change

• Supporting youth-led change

• Accessing resources, services and supports including Indigenous and kaupapa Māori practice

• Increasing community action to challenge violence and model wellbeing.

Assessing current state

During the wānanga, each topic is discussed, and notes are taken on the things that are currently enabling community mobilisation and the barriers to mobilisation. Following discussion on each topic, the community is asked to decide where they sit in terms of community mobilisation by plotting the current state.

Creating an appropriate scale

Initially, a Likert-type measurement scale was proposed to assess the current status. However, questions raised about this approach by E Tū Whānau practitioners were echoed by community-based practitioners and, instead, a mātauranga Māori-informed approach was agreed on.

In the first piloting of the tool, the Kahupō–Toiora Continuum (Kruger et al., 2004; Love et al., 1993) was used with the Ara Poutama design.[6] However, both communities that participated raised concerns about the use of the Kahupō–Toiora Continuum and Ara Poutama for this purpose. The communities said that, because the continuum was linear, there was a top-bottom, good-bad dichotomy intrinsic in measurement, which did not align with Māori thinking.

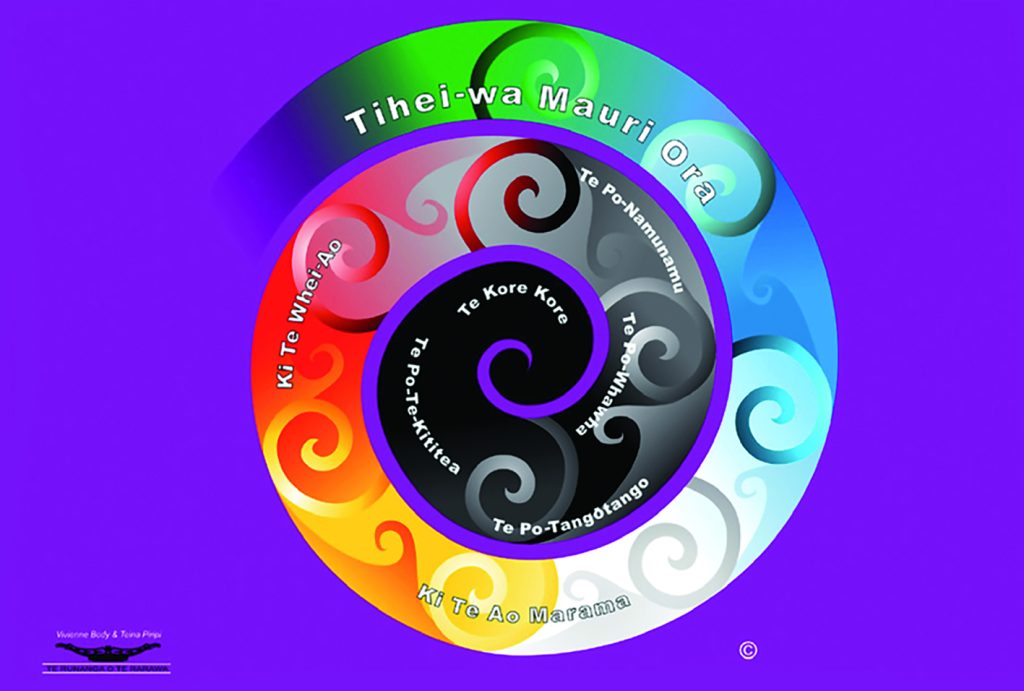

The authors then discovered the Tihei-Wā Mauri Ora construct (Piripi and Body, 2010) and tested this in the second pilot. The Tihei-Wā Mauri Ora construct is based on concepts of the realms of creation according to te ao Māori: Te Kore Kore (state of potential), Te Pō (the deep night), Te Whei-Ao (glimmer of light, coming into being) and Ki Te Ao Mārama (bright day of life). Drawing on creation and re-creation stories and nature, Tihei-Wā Mauri Ora is a dynamic construct (see Figure 10.1).

Tihei-Wā Mauri Ora immediately resonated with Māori practitioners and community members in the second pilot. The construct responded to requests from both communities for a dynamic Māori construct that positioned Te Kore Kore as a state of potential and regeneration, and as a natural part of a process of change, rather than a negative state. The koru shape (spiral motif in kōwhaiwhai patterns and carving) and internal koru within each state of being were seen to embody the dynamic worldview of Māori. Tihei-Wā Mauri Ora was adopted for use in the tool.

Figure 10.1: Tihei-Wā Mauri Ora construct

From Piripi and Body, 2010, p 43. Used with permission.

Following each kōrero, participants were asked to plot where they thought their community was at currently, by placing a star sticker on the Tihei-Wā Mauri Ora image. The result of an assessment includes eight plotted Tihei-Wā Mauri Ora images, along with qualitative notes on the enablers and barriers to mobilisation on each topic or outcome. The results are used to document current state, to inform planning and to assess change over time through ongoing assessments.

Considerations

The authors have identified key considerations for our He Awa Whiria process, around relationships, creating new precedents, ethical data collection and perceptions of evidence quality.

Relationships

A key consideration in this He Awa Whiria process was that it involved people with long-standing and trusted relationships. This meant it was safe to bring in a Pākehā researcher, to share power, and to disrupt the dominant conception of researchers being the experts in the room. Together, the authors negotiated ways of working together and the traditional priorities of researchers (for example, statistical validity over cultural safety and appropriateness) were reversed.

Creating new precedents

It was important to recognise that working within a Crown organisation meant that the structures, processes and accepted practices that the work sat within were informed by Western thinking. This thinking had routinely positioned mātauranga Māori as less important, hard to understand and less robust than Western methods and evidence. Moving towards collective self-assessment provided a good fit with te ao Māori, but was largely without precedent in government spaces. This opened a conversation about new ways of understanding what evidence is meaningful and to whom, and to embracing research processes that work for Māori and communities.

Ethical data collection

The authors were very aware of the ethical challenges and considerations that arise when Crown agencies collect data on Māori communities. The community self-assessment method the tool uses is intended to support self-determination for Māori communities. So, instead of a Crown agency collecting extensive data on communities and sharing a summary back with them, with this approach, only the communities hear the deep and rich data sets that are shared through dialogue, and a summary of this is communicated back to the Crown agency. These data sets include the eight plotted Tihei-Wā Mauri Ora images and brief notes on the barriers to and enablers of change on each topic.

Perceptions of evidence quality

The method used in the assessment tool disrupts what is routinely accepted as quality, or robust, evidence; it is intended as a decolonising approach to assessment. The method is a challenge to the hierarchy of evidence that positions the highest quality evidence as that produced by experts who have no connection to the communities they study. It questions from whose perspective decisions about evidence quality are generally made and whose assessments of quality should be privileged. Part of this disruption is the move away from quantification to a privileging of dialogue within the te ao Māori setting of wānanga.

Conclusion

He Awa Whiria is both a theoretical and a practical model. It enabled the authors to negotiate the complexities of institutional power and whānau preferences in order to develop a tool of use to community and government audiences. This experience of ‘being in the whiria (braiding)’ helped us to explore whose ways of understanding and measuring change count, and to elevate kaupapa Māori ways of working.

In this way, He Awa Whiria enabled innovation between the kaupapa Māori and Western knowledge streams, and a shift towards an approach to measuring community mobilisation that is better aligned to both te ao Māori and a more natural way of incorporating measurement in communities.

The He Awa Whiria approach enabled an important disruption of what is currently accepted as valid measurement. The tool blurs the line between assessment and practice, and disrupts the higher value often placed on external assessment run by experts brought into communities solely to assess progress. The dialogue-based assessment process also supports community mobilisation, by building knowledge, strengthening relationships between those involved in the kaupapa, and increasing critical consciousness about whānau wellbeing and violence within whānau. The assessment tool is an innovative approach to assessing change within communities and is thought to be the first of its kind internationally.

References

Abramsky, T., Devries, K., Kiss, L., Nakuti, J., Kyegombe, N., Starmann, E. … Watts, C. (2014), ‘Findings from the SASA! Study: A cluster randomized controlled trial to assess the impact of a community mobilization intervention to prevent violence against women and reduce HIV risk in Kampala, Uganda’, BMC Medicine, 12(122).

Contreras-Urbina, M., Heilman, B., Von Au, A.K., Hill, A., Puerto Gómez, M., Zelaya, J. & Arango, D.J. (2016), Community-based Approaches to Intimate Partner Violence: A review of evidence and essential steps to action (Washington DC: World Bank Group).

Davis, R., Parks, L. & Cohen, L. (2006), Sexual Violence and the Spectrum of Prevention: Towards a community solution (Enola, PA: National Sexual Violence Resource Center): www.nsvrc.org/publications/nsvrc-publications/sexual-violence-and-spectrum-prevention-towards-community-solution

E Tū Whānau (2020), E Tū Whānau Mahere Rautaki: Framework for change 2019–2023 (Wellington: Ministry of Social Development).

Hann, S. & Trewartha, C. (2015), Creating Change: Mobilising New Zealand communities to prevent family violence (Auckland: New Zealand Family Violence Clearinghouse, University of Auckland).

Krug, E., Dahlberg, L., Mercy, J., Zwi, A. & Lozano, R. (2002), World Report on Violence and Health (Geneva: World Health Organization).

Kruger, T., Pitman, M., Grennell, D., McDonald, T., Mariu, D., Pomare, A., … Lawson-Te Aho, K. (2004), Transforming Whānau Violence: A conceptual framework. An updated version of the report from the former Second Māori Taskforce on Whānau Violence (Wellington: New Zealand Family Violence Clearinghouse).

Lippman, S.A., Maman, S., MacPhail, C., Twine, R., Peacock, D., Kahn, K. & Pettifor, A. (2013), ‘Conceptualizing community mobilization for HIV prevention: Implications for HIV prevention programming in the African Context’, PLoS One, 8(10), 1–13.

Love, M.T.W., Tutua-Nathan, T., Barns, M. & Kruger, T. (1993), Ngaa Tikanga Tiaki i te Taiao: Maori environmental management in the Bay of Plenty. Consultants’ report on Maori environmental management and issues of significance to Maori for inclusion in the Regional Policy Statement (Whakatane: Bay of Plenty Regional Council).

Macfarlane, A. (2009), ‘Collaborative Action Research Network’, paper presented at the CARN Symposium, University of Canterbury.

Macfarlane, S., Macfarlane, A. & Gillon, G. (2015), ‘Sharing the food baskets of knowledge’, in A. Macfarlane, S. Macfarlane & M. Webber (eds), Sociocultural Realities: Exploring new horizons (52–67), (Christchurch: Canterbury University Press).

Michau, L. (2007), ‘Approaching old problems in new ways: Community mobilisation as a primary prevention strategy to combat violence against women’, Gender & Development, 15(1), 95–109.

Piripi, T. & Body, V. (2010), ‘Tihei-wa mauri ora’, New Zealand Journal of Counselling, 30(1), 34–46.

PwC (2016), Investing in Primary Prevention of Family Violence: Discussion paper (Melbourne: Victorian Department of Premier and Cabinet).

PwC, Our Watch & VicHealth (2015), A High Price to Pay: The economic case for preventing violence against women (PwC): [PDF] https://www.pwc.com/gx/en/psrc/publications/assets/high-price-to-pay.pdf

Trewartha, C. (2020a), ‘He Awa Whiria: Braiding the rivers of kaupapa Māori and Western evidence on community mobilisation’, Psychology Aotearoa, 12(1), 16–21.

Trewartha, C. (2020b), ‘Measuring Community Mobilisation’ (PhD thesis, University of Auckland): http://hdl.handle.net/2292/50130

- See: https://etuwhanau.org.nz/ ↵

- Violence includes all forms of abuse, neglect and violation within whānau. ↵

- Primary prevention is a public health approach that works to prevent harm by addressing the root causes, risks and protective factors associated with harmful behaviour (Davis et al., 2006; Krug et al., 2002). The emphasis is on preventing new harms by changing the social conditions, structures and norms that perpetuate harm, and on building protective factors for safety, wellbeing and resilience. ↵

- As defined in section 268 of the Education and Training Act 2020 (NZ). ↵

- The discussion topics are the priority action areas (community mobilisation outcomes) of E Tū Whānau Mahere Rautaki: Framework for Change (E Tū Whānau, 2020). ↵

- The Kahupō–Toiora Continuum is described by Kruger and colleagues (2004, p 15), who state that toiora, or mauri ora, is one of several Māori terms for wellbeing – meaning wellness of both the collective and the individual. It is regarded as the maintenance of balance between wairua (spiritual wellbeing), hinengaro (intellectual wellbeing), ngākau (emotional wellbeing) and tinana (physical wellbeing). Toiora is sustained and restored by experiences of ihi (being enraptured with life), wehi (being in awe of life) and wana (being enamoured with life). In contrast to toiora, kahupō is having no purpose in life, or a state of spiritual blindness. Ara Poutama is the stepped pattern of tukutuku (ornamental lattice work) panels and woven mats, depicting genealogies and also the various levels of learning and intellectual achievement. It is considered by some to represent the steps of Tāne-te-wānanga, the son of Ranginui (Sky Father) and Papatūānuku (Earth Mother), who ascended to the topmost realm of the heavens. ↵