7 He Awa Whiria in psychology:

Health, clinical practice and tertiary education

Dr. Carrie Clifford and Dr. Hitaua Arahanga-Doyle

Introduction

As described in earlier chapters, the He Awa Whiria approach involves the acknowledgement of two streams of knowledge within programme development, implementation and evaluation (Macfarlane et al., 2015). The first stream of knowledge is te ao Māori and the second is contemporary Western science. Importantly, the He Awa Whiria approach contends that value is created through novel insights that either stream may not be able to produce on its own.

Within this chapter, we describe the application of such an approach in two pieces of psychology research, namely, the authors’ respective doctoral theses. The first example described below is research by Hitaua Arahanga-Doyle that looked at the development and application of a brief social-psychology intervention with first-year Māori university students. The intervention drew on mātauranga Māori regarding the importance of whanaungatanga (building relationships) and contemporary Western social psychology theories. The second example is research by Carrie Clifford, which explored the use of pūrākau (Māori legend or story) and Māori storytelling practices in contemporary mental health settings. Her research involved qualitative approaches (for example, interviews, focus groups) with a wide range of health professionals and kaumātua (Māori elders, persons of status within the whānau) to explore the use, benefits and broader considerations to the therapeutic use of pūrākau. While these two projects are independent pieces of work, each author aimed to provide holistic, strengths-based solutions to promote Māori health and wellbeing within the discipline of psychology.

Both pieces of research were conducted within the field of psychology – tertiary education and mental health services – which continues to underserve many Māori, leading to well-documented health and education inequities (Reid and Robson, 2006; Theodore et al., 2018). Historically, solutions to these inequities have ignored Māori perspectives in favour of Western approaches. The two projects discussed in this chapter demonstrate the applicability of the He Awa Whiria approach to centring a genuine partnership of mātauranga Māori and Western psychology; it has the potential to provide innovative and creative solutions to some of the most significant challenges within psychology. Such an approach aims to contribute towards equity and wellbeing not only for Māori but for all New Zealanders.

We also want to note our whakapapa (genealogy) as Kāi Tahu Māori. In their writings on the He Awa Whiria approach, Professor Angus Macfarlane and Associate Professor Sonja Macfarlane have noted that the imagery of the model itself is drawn from the braided rivers that feature throughout the landscape of Te Waipounamu (the Māori name for the South Island of New Zealand). This area is the predominant rohe (region) belonging to the iwi Kāi Tahu, meaning that this imagery speaks directly to both of our whakapapa. In addition, the core concept within the He Awa Whiria approach – bringing together mātauranga Māori and contemporary Western science – effectively mirrors our dual ethnic identities as Māori and New Zealand European. This dual ethnicity is not unique to the two of us, given that more than half of the Māori population in New Zealand also identify as both Māori and European. However, the integrated way of thinking inherent to the He Awa Whiria approach means that using it within our respective PhD research was appealing, because it allowed both of us to apply a methodology that personally reflects us as researchers, our lived experiences and our educational journeys. We trust that this integrated and personal perspective is echoed throughout this chapter, in addition to our discussion and illustration of the general strengths and benefits of utilising the He Awa Whiria approach within psychology in New Zealand.

Psychology in New Zealand

Put simply, psychology is an attempt to study, describe and explain the mind and behaviour. However, psychology is complex. This complexity is not a fault but a necessity, as it reflects the complexity of us, as humans. However, throughout much of mainstream psychology there has been a prevailing tendency to view the psychological world through a single, Western lens. Given this, it is possible that many psychological theories and ideas may only apply properly to people from this same Western cultural context (Henrich et al., 2010). This Western approach fails to capture psychological processes that come from, and which assist, other groups of people. In line with this thinking, the 2018 Waitangi Tribunal claim lodged by Dr. Michelle Levy, a Māori psychologist and academic, raised concerns about the “Crown’s failure to ensure psychology, as an academic discipline and profession, adequately meets the needs and demands of Māori” (Waitangi Tribunal, 2018, p 1).

Within much of the psychology research and practice in New Zealand, Western worldviews are privileged and predominantly viewed as the norm (NiaNia et al., 2017; Waitoki et al., 2018). Sonja and Angus Macfarlane have described how a significant motivation for their theorising and development of the He Awa Whiria approach is the recognition that, for much of New Zealand’s history, a Western approach to knowledge was the only approach that was valued. If Māori perspectives were taken into account, particularly within attempts to address disparities between Māori and non-Māori, then they tended to be viewed in contrast or competition to more ‘contemporary’ approaches. The outcome of such thinking was a view that the work to address disparities should be done either entirely through Western methodologies and programmes or mātauranga Māori methodologies and programmes (Macfarlane et al., 2015). As Durie (2004) notes, this dichotomous thinking can miss the creative potential of Indigenous knowledge applied in parallel with other knowledge systems.

As psychology graduates of mainstream Western institutions in New Zealand, both authors of this chapter have been trained and have expertise within the dominant Western approach. However, as Māori, we are also keenly aware of the limitations of this tradition. Thus, throughout our PhD research, we both attempted to integrate our contemporary psychological knowledge with our understanding of a more holistic psychological worldview, namely, one that better values and incorporates mātauranga Māori. By using the He Awa Whiria approach within our research, we attempted to create, test and present unique insights within the context of tertiary education and mental health/clinical psychology. The two following sections were written by their respective authors, who discuss their research in the first person; in the final section, we return to jointly reflecting and discussing recommendations.

Social psychology and whanaungatanga (Hitaua’s doctoral research)

For much of New Zealand’s history, Māori were denied the ability to meaningfully participate in the education system, and the symptoms of this history continue to produce a range of inequities across the education system as a whole (Blank et al., 2016). A great deal of literature has been written on this topic, and the inequities within the education system are relatively well known in both academia and in the mainstream. Within tertiary education, one notable statistic is the low completion rate for Māori students at university. According to 2020 data from the Ministry of Education, more than one in five (22 per cent) Māori students did not complete the first year of their bachelor’s degree course, and subsequently left university. This statistic was the catalyst for my PhD research. It’s no secret that improving Māori student success (for example, by improving the retention rate) is a complex problem that is unlikely to have a single solution. However, my goal was to try and address educational inequalities at university from a social-psychological perspective, with the hope of developing a practical and applicable method to aid Māori students’ success.

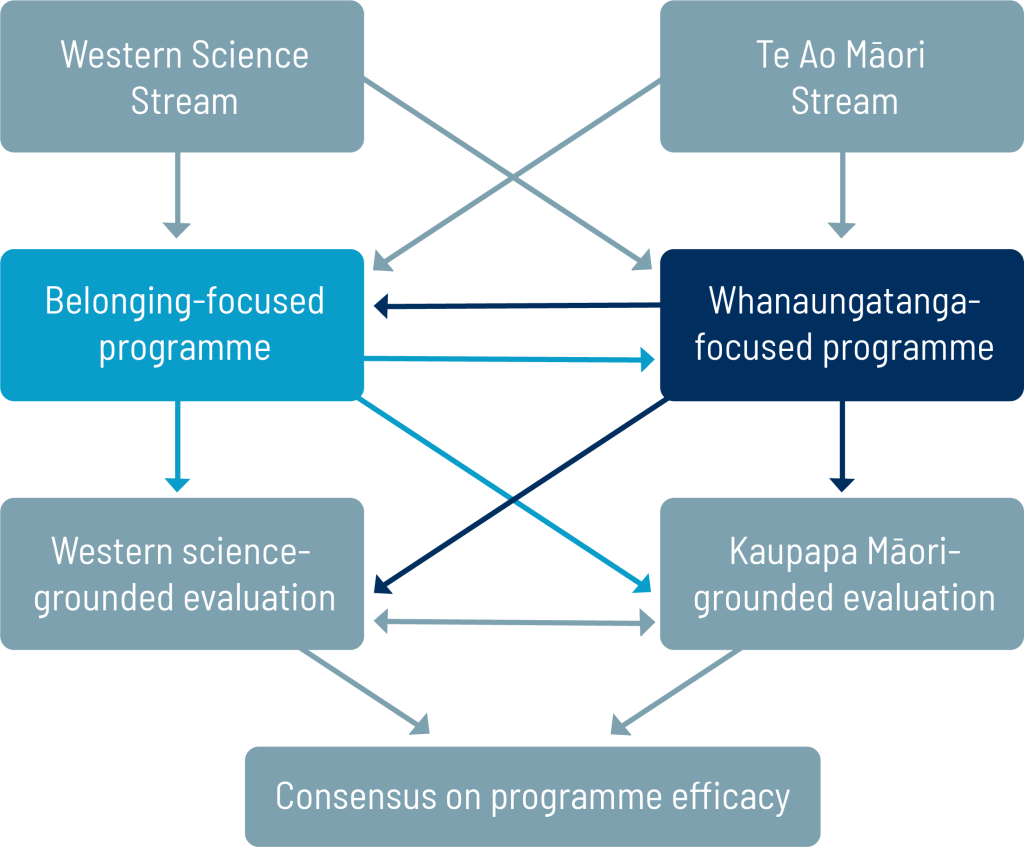

A growing body of research highlights the importance of whanaungatanga as an avenue to improve the outcomes of Māori learners (Bishop et al., 2014). Whanaungatanga – built from the root word ‘whānau’ – is a concept central to te ao Māori and mātauranga Māori, and emphasises family or family-like relationships, as both a cultural value and a social process. These relationships are critical to how Māori view themselves, others and their broader world. In this sense, whanaungatanga doesn’t simply provide a lens for how Māori see their world, but also tangible instructions on how to properly navigate it. Within my research, this importance of whanaungatanga and its potential impact for Māori learners was the core knowledge drawn from the te ao Māori stream of the He Awa Whiria approach (see Figure 7.1).

Keeping with the language of the He Awa Whiria model, the knowledge drawn from the other stream – the Western-science stream – related to contemporary social-psychology approaches towards human behaviour (see Figure 7.1). Within modern social psychology, one of the most influential theories in describing and explaining human behaviour is the ‘social identity perspective’. Developed in the 1970s, this theory describes how people are profoundly affected by the groups they identify with and belong to, particularly when group membership is internalised as part of a person’s understanding of their own identity (Hornsey, 2008). One element within this social identity perspective is what’s known as the ‘belonging hypothesis’. This hypothesis contends that a sense of belonging – that is, core relationships with others – is a fundamental human need and that, when achieved, it can be linked to a range of health, psychological and educational benefits.

Figure 7.1: He Awa Whiria model incorporating concepts of social belonging and whanaungatanga

From AGCP, 2011 (p 46). Licensed for adaption and re-use under (CC-BY) 4.0.

In my research, I identified the notable parallels between whanaungatanga and the belonging hypothesis, regarding the importance of relationships within psychological processes. This formed the major conceptual foundations of research. Namely, the research integrated the two knowledge systems within a brief social psychology intervention with the aim to improve outcomes for Māori tertiary students. The intervention used within this research was adapted from American interventions termed the ‘wise-intervention framework’. Interventions from this framework aim to re-shape how individuals construe an environment and view themselves within that environment. The clearest example of the strength of this approach is Walton and Cohen’s (2007) work with African-American university students in the United States.

Research in the US has repeatedly found that African-American students tend to hold doubts about whether they belong at university institutions and, when they experience challenges, may take this as confirmation that they do not belong (Walton and Cohen, 2007). Walton and Cohen used a brief intervention that utilised contextually targeted storytelling to improve the sense of belonging and long-term academic outcomes for African-American students. The primary aim of the intervention was to alleviate the way that African-American first-year students may view particular social experiences as evidence that they do not belong. Critical to the intervention was the recognition that African Americans do face a range of adverse experiences – such as negative and perverse stereotypes, and discrimination – within university settings in the US. It is off the back of this discrimination that their sense of belonging may come into question.

Walton and Cohen’s intervention involved three key stages. Stage one had African-American students read nine carefully written statements, ostensibly by older students, which described the social challenges faced during the first year of university. The statements did not try to undersell the social challenges as easy; rather, they simply described that the students had faced them and managed to overcome them with a focus on social support, social identity and the eventual acceptance from others. Stage two then asked the students to write a one-page statement about the social challenges that they had faced and overcome that were similar to those they had just read about. By asking the students to write about their own experiences, this stage aimed to make the psychological processes of belonging at university (or a lack thereof) personally relevant to each student. Finally, stage three reinforced the intervention’s themes around the importance of belonging, by having the students read their personal statement out loud to a video camera. This stage utilises a psychological theory called ‘saying is believing’, which contends that when people freely and outwardly talk about a message, they are more likely to internalise the message they are speaking and tend to exhibit long-term behaviour change consistent with that message (Walton and Cohen, 2007). The results of their intervention found that African-American students (and not Caucasian North American students) showed a decrease in belonging uncertainty (that is, they were not as uncertain about the sense of fit at university), and this was linked to a number of positive outcomes, such as increased three-year grade-point averages and positive study habits.

While there are many socio-cultural differences between the African- American students in the US and Māori students in New Zealand, the two groups are often compared, due their similar numerical inequities across a range of domains and the fact that both groups share a similar proportion of the general population in their respective countries (approximately 16 per cent: Blank et al., 2016). Given the success of Walton and Cohen’s intervention, the core focus of my PhD research was to adapt their intervention for Māori university students. In particular, I asked whether an adapted intervention framework could be an effective tool to help Māori tertiary students maintain their sense of belonging at university. Whanaungatanga is a core cultural value within te ao Māori and, given the parallels between social-psychological conceptions of belonging and whanaungatanga, it was hypothesised that maintenance of belonging using this intervention may be particularly beneficial for Māori students.

Across a range of analyses, my results found no significant improvement in belonging or social identity for Māori first-year university students who participated in the intervention, over a Māori student control group (or non-Māori first-year students in both an intervention or control group). It’s also important to note that there was no decrease in these belonging or social-identity measures either. Overall, the quantitative results were largely neutral and do not appear to offer evidence in support of a wise-intervention framework to impact belonging (or by theoretical association, whanaungatanga) for Māori university students. While our results were not in line with Walton and Cohen’s original work, I took an additional step, not included in their framework, and conducted a qualitative analysis of the Māori and New Zealand European students’ personal statements – statements in which the participants described their experiences as first-year students.

Three main themes were generated by the participants’ written statements. The first theme focused on the importance that the students placed on building strong friendships and social-support structures. Significantly, the students also noted that their most valuable relationships took time to develop. The second theme focused on the students’ recognition of the difficulties of university. The students acknowledged that university has its challenges, but the challenges are what they learn from. The third theme focused on the students’ perceptions of having to become independent at university and the distinct difference in the way that Māori and New Zealand European students described this process of independence. Māori students tended to describe this process of having to learn to be more independent as a challenge to overcome, for example: “[University] is a lot of work and a lot of new things to learn in terms of study, lectures and independence. I really struggled.” In contrast, the New Zealand European students tended to describe this process of becoming independent as a basic goal they expected to reach, for example: “I wasn’t that worried about being independent … having to do my own washing, being in charge of my own life.”

Kraus and Stephens (2012) describe the university environment in the United States as one that perpetuates particular cultural norms by most often focusing on independent norms over more interdependent norms. Within the New Zealand context, Brougham and Haar (2013) write that “Māori are a collectivistic people living within a largely individualistic country” (p 1143). These ideas speak to the third theme related to independence as students. The New Zealand European students seemed to perpetuate the common independent cultural norms, as described by Kraus and Stephens (2012), whilst the Māori students played out the collectivistic description of Brougham and Haar (2013).

With an eye to the future, implementing an approach that speaks more directly to the socio-cultural environment will be critical. A wise intervention that takes a more context-specific approach to the experiences of Māori students (for example, their perceptions of independence) will likely be more effective in altering social outcomes – that is, an intervention that explicitly describes the identity and distinct experiences of Māori students. This is in comparison to the generalised approach taken within my research, which promoted a more general, core social motive (in this case, belonging).

Finally, the potential for an intervention as described here is enabled by a sincere understanding of the structural and social context, not ignorance of it. This recognition of the contextual factors speaks to an important point about wise interventions, in that they are just one tool that may be used to try and create equity:

[Wise] interventions do not, on their own, improve achievement, health, or relationships. They rely on existing resources in peoples and systems and aim to help these function optimally to improve outcomes. (Walton and Wilson, 2016, p 17)

This is clearly true here in New Zealand. Long-term change to assist Māori tertiary students is most likely to come only from a combined approach that pairs individual and psychological concerns with relevant structural, systemic and social changes.

Braiding mātauranga Māori and contemporary mental health services (Carrie’s doctoral research)

In this section, I explain the context and rationale for using a He Awa Whiria approach, and detail how the approach guided my research methodology and positively impacted the results and conclusions of my doctoral research. The dominance of Western approaches and worldviews within psychology is well documented by numerous Māori and Indigenous researchers and psychologists (NiaNia et al., 2017; Waitoki et al., 2018). Representative of the broader discipline of psychology, the profession of clinical psychology is largely normed off Western populations and notions of mental health and, consequently, clinical practice and psychological approaches reflect such notions.

Given this context, the key motivation for my doctoral research was to explore Māori approaches to wellbeing and healing, in particular, the use of pūrākau and intergenerational Māori storytelling practices in contemporary mental health settings. Pūrākau are Māori narratives and stories “containing philosophical thought, epistemological constructs, cultural codes and worldviews” (Hikuroa, 2017, p 6). Pūrākau and other Māori oral traditions are central to the preservation and transmission of mātauranga Māori. While many Māori have long asserted the wellbeing benefits of pūrākau, there has been comparatively little research on using such practices in mental health settings. One notable exception is the work of Lisa Cherrington and Diana Kopua (née Rangihuna; Cherrington and Rangihuna, 2000). As such, my doctoral research aimed to explore the current and potential future use of pūrākau in contemporary mental health settings in New Zealand. The study involved interviews with 31 mental health workers or kaumātua (22 Māori, 9 non-Māori; 15 one-on-one interviews, 2 focus groups), who had knowledge of, and experience using, pūrākau in contemporary mental health contexts. The intention was to explore the uses of pūrākau from a wellbeing perspective, including observed benefits and broader considerations.

In my research, I used He Awa Whiria to provide an overarching theoretical framework to acknowledge both mātauranga Māori and Western psychology, and to navigate the interface of these two knowledge streams. While I initially positioned He Awa Whiria as an overarching framework, I found many layers in which the He Awa Whiria approach could be applied. For instance, He Awa Whiria provided a framework to reflect upon my personal and professional positioning and motivations, and on the research aims concerning both knowledge streams. Such reflection ensured that I had the appropriate knowledge, skills and supervision to work at the science–mātauranga Māori interface. My supervision team contained academic experts in both Western science and mātauranga Māori. The He Awa Whiria approach encouraged me to draw upon Māori and Western research methods and ethical principles. I therefore drew upon kaupapa Māori research principles and theory (see Smith, 1999) to guide my research process and engagement with participants, alongside Western-psychology, qualitative-research methods to provide a process to collect and analyse data. The convergence of oral storytelling and qualitative research methods aligns with Durie’s (2004) assertion that the two knowledge systems are often not at odds. Critically, the use of He Awa Whiria also makes explicit that current psychological therapy and associated approaches predominately come from the Western knowledge stream.

Beyond the layers of application, consideration of the wider historical, political and cultural context in which research takes place was essential (Smith, 1999). Utilising the He Awa Whiria model allows the past, current and potential future state of the two rivers – in particular, an awareness of the historical and ongoing marginalisation of mātauranga Māori – to be considered. Therefore, to work successfully at the interface, knowledge of te ao Māori and mātauranga Māori, and an appreciation of the history of Māori research and the oppression of Māori knowledge systems, is essential.

He Awa Whiria helped guide decision-making throughout the research process. This included, at the project’s inception, defining the research project’s scope and also informing the questions I asked, for example, about the observed therapeutic and cultural-therapeutic benefits of pūrākau use. Such an approach may also inform decisions about appropriate measures of, and ways of collecting, data. In the current research, an absence of culturally appropriate quantitative-research measures, and the alignment of Māori storytelling with qualitative research methods, lead me to use a qualitative approach. Likewise, He Awa Whiria informed how I defined and selected participants. I considered who would be deemed knowledgeable experts through both a Māori and a Western lens. This lead me to interview both kaumātua and those with Western psychology education. Cumulatively, such decisions positively impacted the data collected and the research results.

He Awa Whiria also prompted me to consider my findings in the context of the two knowledge streams, and to make recommendations relevant both to the two streams and to the science–mātauranga Māori interface. For example, recommendations around the revitalisation and development of cultural practices were relevant to the mātauranga Māori knowledge stream. The benefits contributed to the literature surrounding narratives to the Western-science stream, while recommendations for the science–mātauranga Māori interface included the development of pūrākau therapeutic practice and workforce development. It is also important to consider what appropriate dissemination looks like in the context of both streams. While Western research institutions are often geared towards Western outputs – such as journal articles – consideration of outputs relevant to the Māori knowledge stream and communities, and to the interface, may allow for additional, or in some cases more meaningful and transformative, outcomes. As evident in the above examples, at multiple time points He Awa Whiria was helpful for reflection and for guiding research decisions to ensure meaningful application and research.

Taking the He Awa Whiria approach led to the development of 16 themes surrounding the use of pūrākau in mental health settings and associated cultural, psychological and therapeutic benefits. The research also identified broader considerations relevant to the use of mātauranga Māori and Māori cultural practices in mental health settings and in the broader psychology discipline. Such results, gained through employing the He Awa Whiria approach and the methodology outlined, included a holistic understanding of the use of pūrākau in mental health settings and a broad understanding of the benefits in relation to the therapeutic process, as well as psychological and cultural benefits, which I would have been unlikely to discover if I, as a researcher, employed only one worldview. Given the approach, the themes were reflective of and relevant to both mātauranga Māori and Western science, and the interface. For example, the results detail several therapeutic and cultural benefits of using pūrākau in mental health settings and beyond; these include identity development, providing intergenerational wisdom and guidance, and a sense of belonging and connection to place. Likewise, the results highlighted the importance of a clinician’s cultural and clinical knowledge. By utilising this approach, I was able to conclude that pūrākau provide a multifaceted approach to hauora (Māori holistic notions of health and wellbeing): helping to process distress and grief; fostering cultural, psychological and relational aspects of wellbeing; and positively contributing to the overall therapeutic process. This makes pūrākau a holistic and effective therapeutic modality. Consequently, the research documented the value in, and calls for, the development of Māori therapeutic approaches to provide “positive, high-quality healthcare interactions that support Māori ways of being” (Graham and Masters-Awatere, 2020, p 193).

As my research developed, I also had the opportunity to interview mental health workers who use Native American, Alaska Native and Native Hawaiian storytelling. The aim of this second study was to understand the use, benefits, opportunities and barriers to Indigenous storytelling in a context outside New Zealand. Study two involved one-on-one interviews with nine mental health workers and elders (eight Indigenous, one non-Indigenous) with knowledge and experience using Native American, Alaskan Native and Native Hawaiian storytelling practices in mental health settings. At this stage, I had to consider what the He Awa Whiria approach would look like in an international context. Including another Indigenous knowledge stream meant that there were multiple conversations across Māori and Native American, Alaska Native and Native Hawaiian knowledge streams, within the broader Indigenous river, and across the river with Western science. Drawing upon the essence of the He Awa Whiria model, I was again able to navigate the research process in a way that gave independent acknowledgement to each knowledge stream, before respectfully examining the interface of Native American, Alaska Native and Native Hawaiian, Māori and Western knowledge streams. Despite stories and storytelling practices being unique to each Indigenous community, participants in both studies valued storytelling as an intergenerational wellbeing practice that promotes a holistic and culturally relevant therapeutic approach. The results also highlight that Indigenous healing practices, such as storytelling, are often invisible or marginalised within psychology, thus limiting the potential therapeutic outcomes (Clifford, 2022).

In interviewing participants about their use of Māori healing practice in Western-psychology spaces, three critical reflections regarding the intersection of mātauranga Māori and Western psychology arose, which are relevant to the use of He Awa Whiria:

1. a caution that we do not pull mātauranga Māori through a Western lens or frame of reference;

2. the importance of investing in both knowledge streams, particularly the need to invest in the development of mātauranga Māori through kaupapa Māori research, given the historical marginalisation in research; and

3. being mindful of the practical realities, including the available workforce and resourcing, of implementing such initiatives and utilising mātauranga Māori in psychology.

In my own reflection, I add to these points by also encouraging others using the model to be inspired by the differences both within each knowledge stream – that is, mātauranga-a-iwi/hapū (Māori knowledge specific to an iwi or hapū) within the mātauranga Māori stream – as well as across the knowledge streams, as this can lead to further understanding, insights and innovation.

In sum, He Awa Whiria provided an effective and practical approach to navigating research at the interface of mātauranga Māori and a Māori healing practice and contemporary Western-psychology settings. Consideration of the topic in the context of both worldviews allowed the holistic and wide-reaching mental health benefits of pūrākau to be identified. The approach allowed for both cultural considerations and Western-psychological perspectives to be taken into account, thus building a strong foundation for future research, programmes and practice development in this area. This research demonstrates flaws in the current knowledge hierarchy of psychology, both in terms of the value of Indigenous knowledge and the overreliance on quantitative-research methods and evidence-based practice; this led me to conclude that considering multiple sources of evidence can provide more balance and greater understanding than either approach would alone.

In reflecting on the research process, alongside my experience as a clinical psychologist, I can see the benefits of drawing these two worldviews together in clinical practice in a way that advances health outcomes, and affirms Western psychology and Māori ways of being. It is my belief that He Awa Whiria can be employed in theory development, psychological research of mental disorders and distress, and psychological formulation with individual clients, to advance a more holistic and nuanced understanding of grief, distress and healing. However, the issue remains that very few clinicians have the knowledge and skill to do this – a challenge that is also seen in research.

Chapter discussion and reflections

Parallel in the above two pieces of psychology research is the use of He Awa Whiria to bring together Māori and Western knowledge systems to lead to innovation, enrichment of understanding and, ultimately, the advancement of programme development and clinical practice. We were both driven by the desire to recognise mātauranga Māori and use our psychology education to contribute to the health and wellbeing of Māori and all New Zealanders. To achieve this, we both used He Awa Whiria to guide decision-making – throughout our research process – in an iterative manner. In Hitaua’s research, He Awa Whiria provided an approach to identifying the parallels between whanaungatanga and Western social psychology, and bringing these together to create an intervention specific for Māori tertiary students in a New Zealand context. In Carrie’s research, He Awa Whiria was employed to navigate the distance, and lack of dialogue, between mātauranga Māori and Western knowledge in clinical psychology and psychological practice. This contributed to a more nuanced understanding of the use, benefits and broader considerations in the use of pūrākau – and other Māori cultural practices – in mental health settings, over and above what may have been possible from either singular worldview. More broadly, utilising the He Awa Whiria approach allowed us to consider the interface of Western education, psychology and health alongside mātauranga Māori.

The foundation of the He Awa Whiria approach is that Western science and Māori knowledge streams are acknowledged as distinct and valid in their own right (Macfarlane et al., 2015). As seen in the two pieces of research, the approach allowed us to acknowledge the value within both knowledge streams and adopt an approach that has relevance to the particular research context. Using He Awa Whiria in this way encouraged partnership and inclusive research (Fergusson et al., 2011). As such, we believe that a He Awa Whiria approach is a starting point for honouring the Treaty of Waitangi in research, programme development and clinical practice. The framework encourages researchers to provide evidence and findings, and develop policy, programmes and interventions, that are consistent with the Treaty of Waitangi and align more effectively for Māori. However, we believe that the keys to the successful use of He Awa Whiria are understanding the historical and contemporary context in which it is applied, and considering the ongoing and historical impact of colonisation.

Māori have long used metaphors of the environment to transmit knowledge and to create and foster understanding (Clifford, 2022; Hikuroa, 2016). Here, we believe, lies the power of the He Awa Whiria framework. Not only does it affirm mātauranga Māori and the importance of land-based metaphors, but the braided river metaphor also provides strong visual imagery to guide understanding and implementation of the approach; it also provides a model for reflection, as seen in the two research examples. As researchers, the appeal of using He Awa Whiria in psychology is that it allows us to draw upon multiple systems of understanding, and ways of viewing the world; this can not only lead to innovation, but can also contribute to the number of tools available for educators and clinicians to promote hauora and learning. Critically, for the field of psychology and the ongoing development of Māori programmes and therapeutic approaches, He Awa Whiria still advocates for independent space for the development of mātauranga Māori and Western psychology.

We acknowledge that these are just two examples of the application of He Awa Whiria, which speak to the potential future use of He Awa Whiria in the discipline of psychology and beyond. In another example, Annalisa Strauss-Hughes also uses He Awa Whiria in psychology to navigate Indigenous and Western knowledge to better understand offending behaviour and intervention approaches; this represents a growing interest and acknowledgement of the need and benefits of a He Awa Whiria approach (Strauss-Hughes et al., 2022). We hope that such work inspires other researchers to consider a similar approach in their research, professional practice and theory development. However, we also note that every research project is different, and researchers should take an individualised approach and application of He Awa Whiria to ensure the best fit with their research area of interest. Furthermore, both authors agree that kaupapa Māori research is vital to advance psychology in New Zealand, and that He Awa Whiria does not replace this need, and should not detract from or replace this important work. Our hope is that, with increased use of He Awa Whiria and similar approaches, there will be further advancement in psychology, so that it can represent the many knowledge systems of the world and, in New Zealand specifically, te ao Māori concepts.

While we are optimistic about such potential benefits, we share concern about the possible misuse of He Awa Whiria – namely, its use only where elements of mātauranga Māori easily fit into Western ideas and frameworks. We stress that this is not the meaningful use of He Awa Whiria we advocate for, and that we do not believe such an approach will lead to the transformation we envisage. Meaningful use of He Awa Whiria involves an understanding and appreciation of each knowledge stream, followed by a considered approach to bringing the two together in a way that recognises and upholds the value in both. We believe those engaging in He Awa Whiria must understand both knowledge systems and reflect deeply on the purpose of the model first, before engaging in the approach.

We see it as critical that researchers consider the motivations and aims of research or programme development, and also the positionality, knowledge and skills of those involved (researchers, programme developers, advisors, etc.). Furthermore, it is beneficial to take a historical lens, so as to understand the context to which He Awa Whiria is applied, the potential opportunities and challenges of implementing He Awa Whiria, and the necessary approach and resources required in a specific discipline or area.

He Awa Whiria helps guide the decision-making process; it impacts the questions we ask, the scope of projects and, ultimately, impacts findings and the narratives we tell. Academia and the discipline of psychology have a long history of deficit narratives about Māori people and our health. As seen in the two research examples, He Awa Whiria as an approach moves us beyond this positioning and encourages us to look at the strengths of both knowledge systems. Further, the approach provides an opportunity to utilise te ao Māori, both in preventative programme development – as seen in Hitaua’s research – and in mental health services delivery, as illustrated in Carrie’s example.

Currently, within the discipline of psychology, we see an increased appreciation of mātauranga Māori; however, for many in the profession, there is limited knowledge of both worldviews and scarce or undervalued successful examples of how to bring the two knowledge streams together. We both believe that workforce development, and investment in Māori psychology and curriculum development are critical. He Awa Whiria can enhance understanding and innovation in psychology research (including research design, methods and evaluation), theory and practice. This is necessary for the future direction of the discipline, and also allows space for each knowledge system to continue to develop independently, thus allowing for advancements in both Māori and Western-science streams. However, given the historical oppression and decades of under-resourcing and under-valuing of mātauranga the Māori knowledge stream, we assert that investment in the mātauranga Māori knowledge stream is paramount, in order for the He Awa Whiria approach to truly take its place.

Concluding comments

With the increasing discussion around the importance of mātauranga Māori in psychology research and practice, and in the health sector more broadly, an approach that meaningfully brings together Western and mātauranga Māori knowledge systems is critical. In this chapter, we have detailed our use and application of the He Awa Whiria approach in psychological research, spanning programme development and clinical practice. Drawing upon our experiences and reflections, we encourage meaningful use of the He Awa Whiria approach, which requires a deep appreciation and understanding of the model, both knowledge systems and the context in which the model in applied. We believe this includes acknowledging contemporary and historical factors, and considering how to effectively and appropriately bring together two knowledge systems in a way that protects and values the mana of both systems, and that allows for innovation and advancement to take place. The question is not whether we should use a He Awa Whiria approach in psychology, but how we can do so in a way that maintains the integrity of mātauranga Māori and leads to positive outcomes.

As demonstrated in our research, approaches to psychological research, theory development, practice and education that value both Western and Māori knowledge systems allow us to build a more comprehensive understanding of relationships, grief, distress, healing and wellbeing. In the future, we hope that the psychology discipline reflects He Awa Whiria, values and advances both knowledge systems, and creates a truly unique psychology representative of New Zealand. These same sentiments around the sharing and building of knowledge are echoed in the words of Sir Hirini Moko Mead (Mead and Grove, 2004, p 9):

Wisdom is universal and is not confined by generations, by oceans or by cultures. It is part of the legacy of humankind.

![]()

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge our PhD research supervisors for their guidance in the presented research. Hitaua Arahanga-Doyle would like to acknowledge Dr. Damian Scarf and Associate Professor Jackie Hunter. Carrie Clifford would like to thank her doctoral supervisors Professor Harlene Hayne, Dr. Jules Gross and Dr. Mike Ross, and those who participated in her research.

![]()

References

Arahanga-Doyle, H.G. (2021), ‘Blending whanaungatanga and belonging: A wise intervention integrating Māori values and contemporary social psychology’ (PhD thesis, University of Otago): https://hdl.handle.net/10523/12406

Bishop, R., Ladwig, J. & Berryman, M. (2014), ‘The centrality of relationships for pedagogy: The whanaungatanga thesis’, American Educational Research Journal, 51(1), 184–214.

Blank, A., Houkamau, C. & Kingi, H. (2016), Unconscious Bias and Education: A comparative study of Māori and African American students (Oranui Diversity Leadership): [PDF] http://hautahi.com/static/docs/BlankHoukamouKingi.pdf

Brougham, D. & Haar, J.M. (2013), ‘Collectivism, cultural identity and employee mental health: A study of New Zealand Māori’, Social Indicators Research, 114(3), 1143–60.

Cherrington, L. & Rangihuna, D. (2000), ‘Māori mythology in the assessment and treatment of Māori tamariki (children) and rangatahi (youth)’, paper presented at Joint RANZCP of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry Conference and Child and Adolescent Mental Health Conference, Auckland.

Clifford, C. (2022), ‘Pūrākau Tuku Iho – Honouring the stories of our tīpuna: An exploration of the use of Māori and Indigenous storytelling in mental health settings’, (PhD thesis, University of Otago): https://hdl.handle.net/10523/15172

Durie, M. (2004), ‘Understanding health and illness: Research at the interface between science and indigenous knowledge’, International Journal of Epidemiology, 33(5), 1138–43: https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyh250

Fergusson, D., McNaughton, S., Hayne, H. & Cunningham, C. (2011), ‘From evidence to policy, programmes and interventions’, in P.D. Gluckman and Office of the Prime Minister’s Science Advisory Committee (eds), Improving the Transition: Reducing social and psychological morbidity during adoloscence (287–99), (Auckland: Office of the Prime Minister’s Science Advisory Committee).

Graham, R. & Masters-Awatere, B. (2020), ‘Experiences of Māori of Aotearoa New Zealand’s public health system: A systematic review of two decades of published qualitative research’, Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health, 44(3), 193–200: https://doi.org/10.1111/1753-6405.12971

Henrich, J., Heine, S.J. & Norenzayan, A. (2010), ‘The weirdest people in the world?’, Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 33(2–3), 61–83.

Hikuroa, D. (2017), ‘Mātauranga Māori – The ūkaipō of knowledge in New Zealand’, Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand, 47(1), 5–10: https://doi.org/10.1080/03036758.2016.1252407

Hornsey, M.J. (2008), ‘Social identity theory and self-categorization theory: A historical review’, Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 2(1), 204–22.

Kraus, M.W. & Stephens, N.M. (2012), ‘A road map for an emerging psychology of social class’, Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 6(9), 642–56.

Macfarlane, A. (2012), ‘“Other” education down-under: Indigenising the discipline for psychologists and specialist educators’, Other Education, 1(1), 205–25.

Macfarlane, S., Macfarlane, A. & Gillon, G. (2015), ‘Sharing the food baskets of knowledge: Creating space for a blending of streams’, in A. Macfarlane, S. Macfarlane & M. Webber (eds), Sociocultural Realities: Exploring new horizons (52–67), (Christchurch: Canterbury University Press).

Ministry of Education (2020), ‘Attrition and retention’, Tertiary Education Statistics – Retention and Achievement.

NiaNia, W., Bush, A. & Epston, D. (2017), Collaborative and Indigenous Mental Health Therapy: Tataihono, stories of Māori healing and psychiatry (New York: Routledge).

Reid, P. & Robson, B. (2006), ‘The state of Māori health’, in: M. Mulholland (ed.), State of the Māori Nation: Twenty-first century issues in Aotearoa (15–27), (Auckland: Reed).

Smith, L.T. (1999), Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous peoples (London: Zed Books).

Strauss-Hughes, A., Ward, T. & Neha, T. (2022), ‘Considering practice frameworks for culturally diverse populations in the correctional domain’, Aggression and Violent Behavior, 63, 101673: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2021.101673

Theodore, R., Tustin, K., Gollop, M., Taylor, N. & Poulton, R. (2018), ‘Equity in New Zealand university graduate outcomes: Māori and Pacific graduates’, Higher Education Research & Development, 37(1), 206–21: https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2017.1344198

Waitangi Tribunal (2018), ‘The psychology in Aotearoa claim: Statement of claim: WAI2725’: [PDF] https://forms.justice.govt.nz/search/Documents/WT/wt_DOC_137601318/Wai%202725%2C%201.1.001.pdf

Waitoki, W., Dudgeon, P. & Nikora, L.W. (2018), ‘Indigenous psychology in Aotearoa/New Zealand and Australia’, in S. Fernando & R. Moodley (eds), Global Psychologies (163–84), (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan): https://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-349-95816-0_10

Walton, G.M. & Cohen, G.L. (2007), ‘A question of belonging: Race, social fit, and achievement’, Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 92(1), 82–96: https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.92.1.82

Walton, G.M. & Wilson, T.D. (2016), ‘Wise interventions: Psychological remedies for social and personal problems’, Psychological Review, 125(5): 617–55.