3 He Awa Whiria and early literacy:

The emancipatory power of a braided rivers approach

Dr. Melissa Derby and Associate Professor Sonja Macfarlane

Introduction

It is widely accepted that literacy plays a critical role in contributing to positive experiences and outcomes, both in education and life in general. The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) defines literacy as a fundamental human right, which is intrinsically important for human development and wellbeing (Derby, 2018). In Aotearoa New Zealand, research on aspects of literacy has been conducted, primarily, in English-medium classrooms, and, to a lesser extent, in te reo Māori immersion settings. However, comparatively few studies have explored the significance of literacy in home environments where children are exposed to both English and te reo Māori.

Our research explored early literacy development with bilingual four year-old children attending a dual-language (te reo Māori and English) early childhood centre in Christchurch, New Zealand. Our study focused specifically on two key cognitive skills, which are widely recognised as playing a critical role in children’s emerging literacy. The first skill was phonological awareness, which can be broadly defined as an awareness of the sound structure of spoken words. The second skill was vocabulary knowledge, which refers to children’s ability to understand the meaning of words.

This chapter describes our study, and then locates it in the context of the He Awa Whiria framework, before giving details about each stream as it applied in this context. The chapter then outlines how He Awa Whiria influenced each phase of our study, and highlights some of the key findings. It describes the benefits brought about by He Awa Whiria, and concludes by offering some key considerations for using He Awa Whiria as an emancipatory framework to guide the development, planning and execution of research.

Describing our study

Eight whānau and their preschool children participated in the study, with the two criteria for participation being that the children attended Nōku Te Ao (a dual-language early childhood centre) and that they were four years old for the duration of our study. Each child was exposed to te reo Māori in the home, albeit to varying degrees. Whānau had a strong desire for their children to learn and speak te reo Māori, as many had not had the opportunity to learn the language in their own childhoods – hence their desire not only to enrol their child at Nōku Te Ao, but also to participate willingly in our study.

The overarching research question was: “What effect does a homebased literacy intervention have on the cognitive skills associated with children’s emerging literacy?” The intervention, which was adapted from Tender Shoots (Riordan et al., 2022), had two components: Strengthening Sound Sensitivity (SSS), which focused on phonological awareness, and Rich Reading and Reminiscing (RRR), which was concerned with vocabulary knowledge. Our study also explored the influence of whānau as first teachers on children’s literacy development.

Using both English and te reo Māori, eight individual whānau case studies were replicated over a 12-week period, to determine the effect of the intervention on the children’s phonological awareness and vocabulary knowledge skills in both languages. A crossover design was used in our study, where each group completed a portion of the intervention then swapped at the midway point. This allowed for comparison to occur between the two groups, which enabled us to draw more robust conclusions about the effects of the intervention. The various phases of data collection and implementation of the intervention are depicted in Table 3.1 below.

Table 3.1: Phases of data collection and implementation

| Phase One (2 weeks) |

Phase Two (6 weeks) |

Phase Three (2 weeks) |

Phase Four (6 weeks) |

Phase Five (2 weeks) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre-intervention data collection |

Group one (n=4) commences SSS |

Mid-intervention data collection |

Group one (n=4) commences RRR |

Post-intervention data collection |

| Group two (n=4) commences RRR |

Group two (n=4) commences SSS |

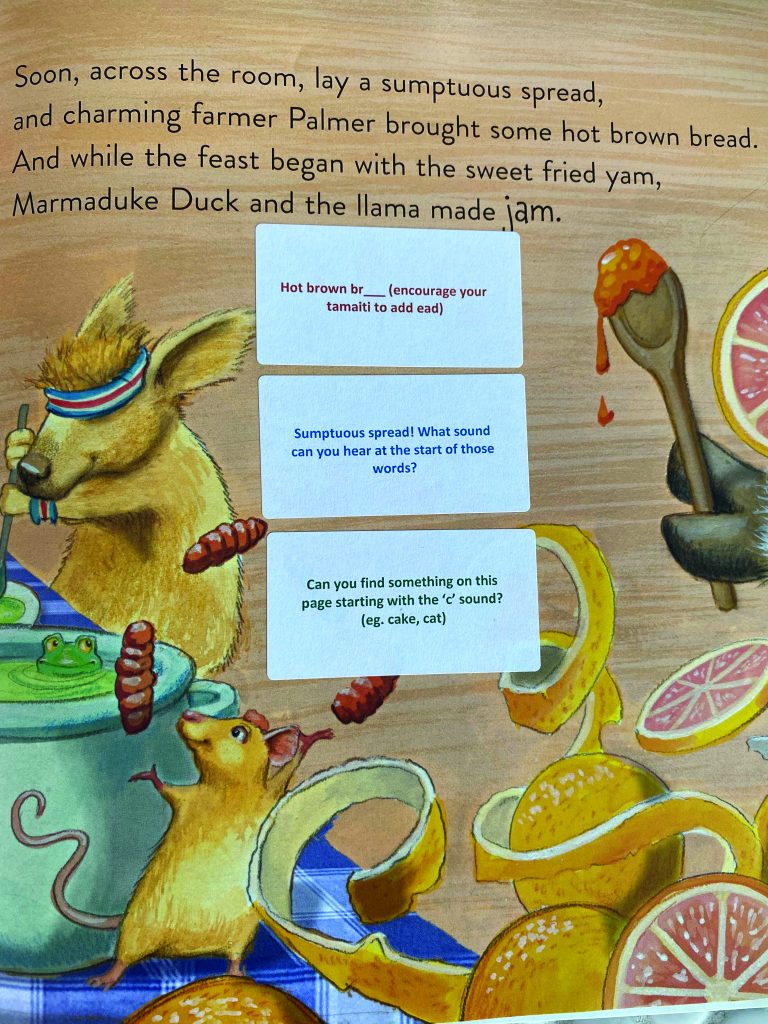

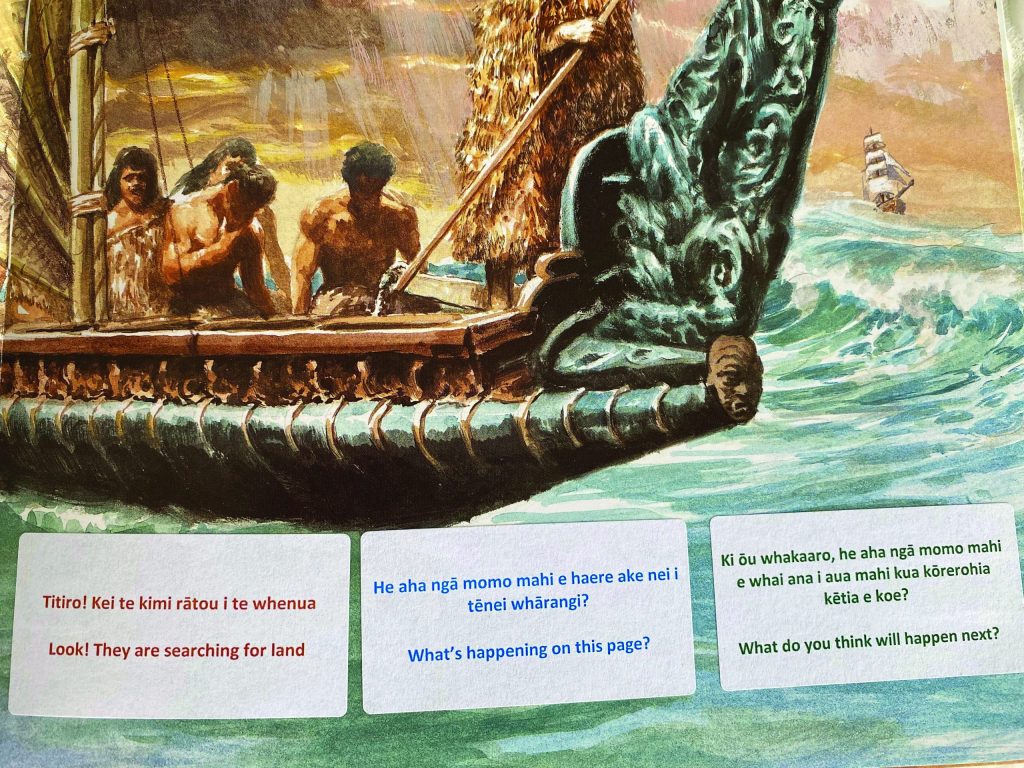

A follow-up round of data collection (Phase Six) was completed six months after the intervention finished, to gauge the sustainability of positive shifts in the children’s early literacy skills. During Phases Two and Four, whānau were actively engaged as implementers of the intervention. Each week, whānau received storybooks and activities in both English and te reo Māori, which they read and completed with their children. Examples of activities included asking open-ended questions in both languages, singing songs, telling stories, reminiscing about the past and engaging in conversations that connected the storybooks to the children’s world. Sticker prompts (see Figures 3.1 and 3.2) were included in the storybooks, to support whānau as first teachers of early literacy skills.

Game-based assessments in both English and te reo Māori were used in Phases One, Three, Five, and at the Phase Six six-month post-intervention follow-up, in order to capture the phonological awareness skills and vocabulary knowledge of the children at those particular points in time.

Figure 3.1: Example of sticker prompts used in the SSS portion of the intervention

(one prompt per reading session, starting with the top prompt)

From Derby, 2019, p 71.

(Storybook page image from McIver, J. & Davis, S. ‘Marmaduke Duck and the Marmalade Jam’. Copyright 2010).

Figure 3.2: Example of prompts used in the RRR portion of the intervention

(one prompt per reading session, starting with the left prompt)

From Derby, 2019, p 72.

(Storybook page image from Drewery, M. & Potter, B. ‘He Tamaiti nō Aotearoa’. Copyright 2004).

He Awa Whiria approach

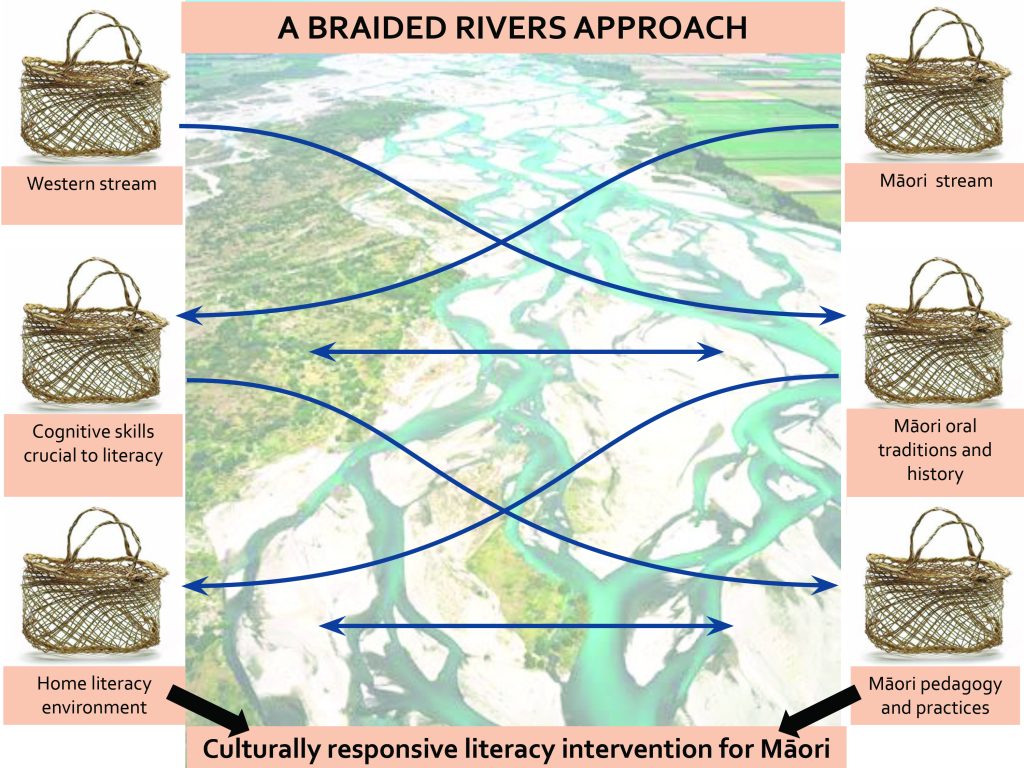

Our study adopted the He Awa Whiria approach, which is an innovative framework that is inspired by both Māori and Western streams of knowledge and practices. Māori history, pedagogical approaches and practices were salient in our study. This, when braided with research from Western scholarship, resulted in outcomes more powerful than either body of knowledge alone could elicit.

This chapter now describes the He Awa Whiria approach, and then applies the framework to our study. The Māori stream includes practices associated with Māori oral traditions, the history of Māori literacy, and traditional pedagogical approaches. More specifically, this includes storytelling and songs as teaching and learning tools, reminiscing about the past to retain rich whānau history, and positioning whānau as first teachers of their children. The Western stream includes research on the role of phonological awareness and vocabulary knowledge in children’s early literacy development, as well as the influence of the home-literacy environment and family literacy practices. Our use of the He Awa Whiria approach in our study created a culturally responsive, home-based literacy intervention that drew from both Māori and Western streams of knowledge to foster children’s early literacy skills (see Figure 3.3).

Figure 3.3 shows how the He Awa Whiria approach was adapted to fit the context of our study. The kete (baskets) under the Western stream refer to research on the cognitive skills associated with early literacy – phonological awareness and vocabulary knowledge – as well as the home-literacy environment and its role in early literacy development. The kete under the Māori stream represent key cultural considerations in our study, specifically Māori oral traditions, history and pedagogy, and the role of whānau in children’s early learning. By blending these streams, a solid and stronger foundation on which to develop a culturally responsive literacy intervention for Māori learners emerged. The sections that follow describe each kete within the respective streams in greater detail.

Figure 3.3: He Awa Whiria approach: culturally responsive literacy intervention for Māori

From AGCP, 2011 (p 64). Licensed for adaption and re-use under (CC-BY) 4.0.

The Māori stream

Māori oral traditions and history, and the role whānau played in traditional pedagogical approaches and practices, formed the Māori stream of our study.

Kete: Māori oral traditions and history

Prior to the arrival of Pākehā in New Zealand, Māori society was oral in nature – knowledge, customs and history were transmitted from generation to generation in oral form. In this society, oral traditions provided substance to and foundations for Māori history, and acted both as a knowledge repository and as a vehicle for passing on knowledge to future generations (Derby, 2016). Aspects of Māori oral traditions continue today as teaching and learning tools, and include the telling of stories and creation narratives, among other things. The importance of talking about the past also remains a prominent contemporary feature in Māori culture. Nowadays, conversations about the past take the form of rich reminiscing, which is a powerful tool for supporting children’s early learning (Reese, 2013).

Significant changes occurred in Māori society when tribal groups encountered the written word. Pākehā settlers began to arrive in 1814, and their numbers slowly increased in the 1820s and 1830s. The settlers brought with them a multitude of different technologies, ranging from agricultural tools and household items to new forms of recording and storing knowledge. Literacy, in the form of the written word, had a profound influence on Māori society, changing its exclusively oral nature.

Māori actively embraced print culture, reading and books. McKenzie cites the “enthusiastic reports back to London of the remarkable desire of the Māori to learn to read, the further stimulation of that interest through native teachers, the intense and apparently insatiable demand so created for books” (1985, p 13) as evidence of the emphatic adoption of literacy by Māori. Exposure to literacy also resulted in social changes, in that it led to a shift in power from resting with those who were masters of oratory to those who possessed the ability to read and write. At the same time, younger generations of Māori actively sought to acquire and master literacy, which acted as a source of pride and prestige for them and their whānau.

Kete: Māori pedagogy and practices

This kete describes Māori pedagogy and practices, as well as the key role of whānau, which was the central unit in traditional Māori society. The influence of whānau on children’s early learning has been widely documented over an extended period (Winiata, 1967). Metge (1976) observes that, traditionally, Māori children received their early education within the confines of the whānau, where they learned genealogies, tribal history, customs, and good language and behaviour through songs and storytelling. The wider whānau unit also played an integral part in the education of children; it further fostered the growth and development of early skills by encouraging children to learn through play, telling stories and mimicking elders, who would use songs and storytelling to recall historical figures and events (Mead, 2003).

The contemporary influence of whānau on their children’s learning and educational achievement was an important consideration in this work. A seminal tribal study that focused on Māori students who were experiencing success at school (Macfarlane et al., 2014) found that whānau played a critical and overarching role in the success of their children. This finding has resonance with a contention made by Sharples (2009, p 5), who states:

Whānau know their children’s potential, and they know how to release it, right from early childhood through to tertiary education. When whānau take ownership and are encouraged to invest in their children’s learning, they are able to place high expectations on their children, and to support them to achieve the highest standards, our goal must be to transfer this experience into all schools.

In summary, whānau have played a pivotal role in children’s learning and educational success, both in historical and contemporary times. This contention – together with those put forward in the kete describing Māori oral traditions and history – comprised the Māori stream in our study, and informed the development of the literacy intervention from a Māori perspective. The sections that follow describe the kete that contributed to the Western stream.

The Western stream

Kete: Cognitive skills crucial to literacy

Phonological awareness

This kete represents the first cognitive skill crucial to early literacy development, specifically phonological awareness. Gillon defines phonological awareness as “an individual’s awareness of the sound structure, or phonological structure, of a spoken word” (2004, p 2). There is a strong link between phonological awareness and early literacy development, with some arguing that a child’s level of phonological awareness is one of the best predictors of reading performance (Hogan et al., 2005).

Justice and Pence (2005) contend that as phonological awareness skills develop, children are able to break down words into increasingly smaller parts and, eventually, into individual sounds. Therefore, phonological awareness is pivotal in supporting literacy skills, because an understanding of the sound structure of words enables children to ‘sound out’ a word in print and then read it. The phonological awareness skills explored in our study were the ability to break words into syllables and to identify the initial sound in a word.

A key consideration in our study was that the phonological awareness contentions were derived from understandings of English-language literacy development. Employing the He Awa Whiria approach meant considering the different language features of English and te reo Māori. Specifically, te reo Māori is a syllable-timed language, with a regular and transparent orthography, whereas English is a stress-timed language, with an irregular, alphabetic orthography. Therefore, given the differences between the two languages, it is possible that the principles around how children develop phonological awareness skills may not apply in the same way in the context of re reo Māori.

In addition to possible differences related to phonological awareness, a further consideration was that, in te reo Māori, rhyme is not a learning or literary feature in the same way it is in English. However, with regards to the initial sound in a word, it was considered unlikely that differences between te reo Māori and English would matter. In other words, a child’s ability to detect the first sound in a word would not be influenced by the linguistic differences evident in each language.

Phonological awareness has received significant attention in New Zealand in recent decades. However, in light of the differences between the languages, we had to ask: Could assessments used to measure phonological awareness skills in English-speaking children accurately capture the phonological awareness capabilities of children who spoke both English and te reo Māori? This was a key consideration in the context of our study, because of its focus on the emerging literacy of bilingual Māori children. Ultimately, applying the He Awa Whiria approach ensured that the linguistic and cultural contexts of the children involved in our research were important considerations in our study.

Vocabulary knowledge

Phonological awareness, while generally recognised as being a key predictor in children’s literacy outcomes, is not the only skill needed to ensure success in literacy. This kete represents another cognitive skill critical to early literacy development – vocabulary knowledge. Once a child has mastered basic decoding and encoding skills, vocabulary knowledge helps a child to determine if a word makes logical or grammatical sense in a text (Gillon, 2018). Children learn most words without explicit instruction, through social interactions – these begin well before children start formal schooling. The ability to understand and remember the meanings of new words depends strongly on how well developed a child’s vocabulary already is. Vocabulary knowledge is cumulative in nature; children with larger vocabularies tend to learn new words with relative ease, compared to children with smaller vocabularies. Therefore, a strong foundation in vocabulary knowledge, in particular before children start school, is a crucial skill that supports them when they learn to read.

Furthermore, there is an interdependent relationship between phonological awareness and vocabulary knowledge; children with larger vocabularies tend to have better phonological awareness skills. As vocabulary develops, children have a growing need to identify differences between similar-sounding words, so they use their phonological awareness skills to identify these differences. Ultimately, the ability to decode a text on its own is not enough; children also need to comprehend the content of the text, in order to draw meaning from it. Their ability to understand text is reliant on familiarity with both vocabulary and the structure of written language. Therefore, phonological awareness and vocabulary are interrelated, and, together, are essential components of learning to read.

Kete: The home literacy environment

This kete describes the home literacy environment and the central role whānau play in fostering early literacy skills. Through their daily experiences, children encounter opportunities to develop and practise their emerging literacy skills in a variety of settings, including in their homes. Language and literacy are typically first encountered at home; the nature of this environment and the practices that occur within it are key to the development of children’s literacy. Research shows that when whānau read books and talk with young children, when a home environment is rich in literacy and language activities, and when the environment is supportive, children’s emerging literacy abilities are greater – as is their motivation to read. Literacy and language activities such as shared book reading and verbal interactions with children, which include reminiscing about past events, asking open-ended questions, singing songs, reciting rhymes, telling stories and playing games, can strengthen children’s literacy development and interest in literacy and learning. Whānau reading practices, such as personal enjoyment of reading and time spent reading, can also influence children’s early literacy. Studies have shown that whānau literacy practices correlate with children’s vocabulary knowledge and phonological awareness skills. Children who observe whānau engaging with reading materials are more likely to engage their whānau in conversation about the materials, and they acquire a richer vocabulary and greater ability to discern between words as a result of these interactions. Therefore, holding purposeful, targeted, interactive conversations with children, as well as sharing books together, can significantly improve children’s emerging literacy.

Discussion

Using He Awa Whiria, and braiding the kete from the Māori and Western streams, resulted in a culturally responsive literacy intervention. This was trialled with children and whānau to determine its effect on the children’s early literacy skills. The findings from the trial revealed that the intervention generated positive shifts in the children’s phonological awareness skills and their vocabulary knowledge. What is depicted here is a selection of the findings. These highlight what emerged from our study in a general sense. For the full suite of findings, refer to Derby (2019).

| Key finding one: | Māori oral traditions, pedagogy and practices can positively influence children’s early literacy skills. |

| Key finding two: | Whānau, in their role as first teachers, can enhance children’s learning experiences and outcomes. |

| Key finding three: | Children who had strong phonological awareness skills in te reo Māori also had strong phonological awareness skills in English, indicating that these skills are transferable across both languages. |

| Key finding four: | Māori oral traditions, pedagogy and practices can have a positive impact on the home literacy environment and practices. |

| Key finding five: | He Awa Whiria as a research framework has the potential to lead to deeper insight into children’s early literacy development. |

The He Awa Whiria framework significantly strengthened our study by providing a pathway to initiate, undertake and synthesise our research. The framework led to the discovery of new knowledge related to children’s early literacy and the role whānau can play in supporting early literacy development.

At each stage of our research, the framework kept us vigilant, aware, balanced, and cognisant of factors we otherwise may have overlooked or underestimated. At the conceptual stage, we applied He Awa Whiria by taking the existing Tender Shoots intervention and culturally enhancing it to ensure its relevance to the community with whom we were working. The focus of Tender Shoots on SSS and RRR resonated with traditional Māori approaches to teaching and learning, specifically the use of storytelling, songs, chants, and consideration of the past to transmit knowledge from one generation to the next. Therefore, these key aspects were braided together using He Awa Whiria as a framework that augmented the intervention for Māori children and whānau.

At the engagement stage of our research, we found that whānau were more willing to participate because of the visibility that He Awa Whiria gave to mātauranga Māori. Whānau also saw the potential benefits that would accrue for their children, and for them as a whānau, as a result of their involvement in our study. Essentially, the intervention, and our study overall, resonated with whānau culturally because of the presence of the Māori stream of knowledge and this meant whānau were willing to participate in our study. Their potentiality was harnessed by them leading the implementation and assessment of the intervention throughout the study, and ultimately their voice was amplified as a result of He Awa Whiria.

The data collection and analysis phase of our research was also enriched by drawing on He Awa Whiria. Previous research from the Western stream had reported that four-year-old children struggle to segment words that are longer than two syllables. However, a number of the participants in the study had first names that were a lot longer than two syllables – in some cases as long as five. He Awa Whiria uncovered a key finding: children in the study could segment words as long as four syllables, in both te reo Māori and English. It was therefore clear that the influence of te reo Māori on the children’s developing language skills meant that they were more familiar with longer words. They were able to transfer that familiarity, and could then segment words longer than two syllables in English. Using He Awa Whiria as a framework to consider both languages together, rather than either on its own, meant we viewed language acquisition as occurring simultaneously and from a position of strength. This view runs counter to the notion that learning another language alongside English can threaten a child’s ability to learn, to converse in and to understand English. Once again, He Awa Whiria facilitated a deeper insight into data collection and analysis that, without the framework, would not have been possible.

The findings from the study illustrated positive changes for children. These are highlighted by the following quotes from whānau in their evaluation of the intervention:

I was really impressed with him [Tama] last week when I read the word nokenoke [worm] he said out of the blue that sounds like mokemoke! [lonely] And he certainly would not have been thinking like that without your project.

Kahu is more likely to ask the meaning of a new word, and during shared book reading, will frequently ask what is going to happen next in the story. I think his speech and listening skills have improved, and believe he is a more confident and engaged learner as a result of the intervention.

During the evaluation phase of the study, which was led by whānau, they indicated that they had already embedded the intervention activities into their daily lives. Therefore, the intervention was sustainable and relevant, and was thus likely to continue to enhance their child’s early literacy and learning. Whānau were also explicitly aware of the difference they were making to their children’s learning experiences and outcomes, which both affirmed and empowered them in their role as first teachers.

Our study’s findings were used to inform the development of the national Ministry of Education (2021) early childhood resource Talking Together: Te Kōrerorero. This resource is designed to support the growth of children’s oral language skills in the early years and – as a result of this study – has a specific focus on bilingualism. Furthermore, He Awa Whiria is the overarching framework that underpins the philosophy, development and implementation of the resource.

Key considerations for using He Awa Whiria

He Awa Whiria prompts us to reflect on a number of key considerations. First, at the conceptual stage of any research undertaking, it is important to ask: Why is the research being initiated? What are the goals and aspirations? Who will benefit from the research? How will the research be conducted in partnership with those involved? These questions serve two main purposes in this context: it brings together both streams of He Awa Whiria and also gives life to the bicultural tenets of the Treaty of Waitangi. Second, during the development phase, it is critical to reflect on what each individual kete from both knowledge streams will represent. In addition to this, it is important to consider how the kete will be braided together to develop the research in a way that serves the aims, aspirations and collaborations of those involved. Third, at the data collection and analysis stages of the research, the following key points are worthy of consideration: that assessment tools are appropriate in order to reflect accurately what is being measured; that the participants understand what the tools are designed to do; and that the analysis considers the findings in a holistic way that reflects both a Māori and non-Māori worldview. Finally, it is critical to disseminate the findings in a way that includes and empowers the participants, and gives them an opportunity to ask questions about the findings. In its essence, He Awa Whiria calls for a partnership and power-sharing approach, and this needs to be reflected at each stage of the research.

Conclusion

In the context of our research, some key findings emerged that were previously not known, and would not have been revealed without the presence of He Awa Whiria at every stage of our research. That in itself is a powerful message, but more than that, the impact of He Awa Whiria uncovering these findings has led to further research, which has already deepened our understanding of early literacy development, bilingualism, and the role of whānau and educators in fostering early literacy skills. Furthermore, a pathway has been set for future research that continues to advance culturally responsive pedagogy and practices, which support early literacy and learning for bilingual children.

In closing, we contend that the absence of He Awa Whiria in our research would have led to the affirmation of previously conceived pejorative notions about mātauranga Māori, whānau potentiality, te reo Māori, bilingualism and early literacy development. Instead, He Awa Whiria enabled these factors to flourish. It was noted at the outset of this chapter that literacy is a human right, which is crucial to success in education and life in general. Our research demonstrates how He Awa Whiria is emancipatory in its essence, both for the participants and for our research findings and their subsequent impact.

References

Derby, M. (2016), ‘Te Whanaketanga o Ngāi Tamarāwaho: The evolution of hapū identity’ (Master’s thesis, Auckland University of Technology).

Derby, M. (2018), ‘“H” is for human right: An exploration of literacy as a key contributor to Indigenous self-determination’, Kairaranga, 19(2), 45–52.

Derby, M. (2019), ‘Restoring Māori literacy narratives to create contemporary stories of success’ (PhD thesis, University of Canterbury).

Gillon, G. (2004), Phonological Awareness: From research to practice (New York: The Guilford Press).

Gillon, G. (2018), Phonological Awareness: From research to practice (2nd edn.), (New York: The Guilford Press).

Hogan, T.P., Catts, H.W. & Little, T.D. (2005), ‘The relationship between phonological awareness and reading’, Language, Speech, and Hearing Services in Schools, 36(4), 285–93.

Justice, L. & Pence, K. (2005), Scaffolding with Storybooks: A guide for enhancing young children’s language and literacy achievement (Newark, DE: International Reading Association).

Macfarlane, A., Macfarlane, S. & Gillon, G. (2015), ‘Sharing the food baskets of knowledge: Creating space for a blending of streams’, in A. Macfarlane, S. Macfarlane & M. Webber (eds), Sociocultural Realities: Exploring new horizons (52–67), (Christchurch: Canterbury University Press).

Macfarlane, A., Webber, M., McRae, H. & Cookson-Cox, C. (2014), ‘Ka Awatea: An iwi case study of Māori students’ success’, Report prepared for Ngā Pae o te Māramatanga, Christchurch: Te Rū Rangahau Māori Research Laboratory.

McKenzie, D. (1985), Oral Culture, Literacy & Print in Early New Zealand: The Treaty of Waitangi (Wellington: Victoria University Press).

Mead, H. (2003), Tikanga Māori: Living by Māori values (Wellington: Huia Publishers).

Metge, J. (1976), The Māoris of New Zealand (London: Routledge & Kegan Paul).

Ministry of Education (2021), Talking Together: Te Kōrerorero: https://tewhariki.tki.org.nz/talkingtogether

Ministry of Social Development (2011), Conduct Problems: Effective programmes for 8–12 year olds, 2011 (Wellington: Ministry of Social Development).

Reese, E. (2013), Tell Me a Story: Sharing stories to enrich your child’s world (New York: Oxford University Press).

Riordan, J., Reese, E., Das, S., Carroll, J. & Schaughency, E. (2022), ‘Tender Shoots: A randomized controlled trial of two shared-reading approaches for enhancing parent–child interactions and children’s oral language and literacy skills’, Scientific Studies of Reading, 26(3), 183–203.

Sharples, P. (2009), ‘Most Māori leave school without NCEA Level 2’, New Zealand Herald: www.nzherald.co.nz/nz/news/article.cfm?c_id=1&objectid=10556383

Winiata, M. (1967), The Changing Role of the Leader in Māori Society (Wellington: Blackwood and Janet Paul).