1 Finding ways to understand evidence in an interagency government setting:

The emergence of He Awa Whiria from an unexpected terrain

Fiona Duckworth and Professor Angus Macfarlane

When it came to recognising kaupapa Māori and mātauranga Māori, an Aotearoa New Zealand conduct-problems project I was supporting in 2007 resembled a parched desert. I, Fiona, say this with some confidence – because in my role with the project’s interagency officials’ group and in supporting the external expert advisory group, I was part of that parched desert. Our plan was to use international evidence and international programmes to address conduct problems in New Zealand. This context unexpectedly became the seminal terrain from which He Awa Whiria, the metaphor of the braided river, emerged.

This chapter describes dynamics that began with little promise, yet, through persistence and scholarship, changed a desert into an oasis, one in which mana is preserved, the privileging of knowledge is disrupted and wellbeing is promoted.

In the mid-2000s, officials from key government ministries (Education; Health; Justice; Child, Youth and Family; and Social Development) were looking for collaborative ways to address severe antisocial behaviour and conduct disorder. It was decided that a cross-government plan to guide shared approaches would be developed. Internationally, particularly in the United States, there had been a large investment in the evaluation of behavioural-management interventions with a specific treatment model and programme fidelity. The evaluation investment, including in randomised, controlled trials, was creating a significant evidence base. This, in turn, drew the attention of the New Zealand government officials and academics involved in developing the cross-government plan, who recommended transitioning to evidence-based, best-practice interventions. Given that the investment in evaluation – and therefore the evidence base – had been in specific US-developed programmes and in one Australian programme, the default position for the New Zealand plan (published in 2007, Interagency Plan for Conduct Disorder/Severe Antisocial Behaviour 2007–2012 (the Plan)) became implementation of those international programmes in this country. The Plan identified a list of prominent, international interventions for behaviour management, such as Incredible Years, Positive Parenting Program, Multisystemic Therapy, Multidimensional Treatment Foster Care and Functional Family Therapy.

An interagency officials’ group – with officials from the ministries noted above – was established to oversee the Plan’s implementation, while an external expert advisory group would help guide implementation and service development. This Advisory Group on Conduct Problems[1] (AGCP) was to “comprise leading researchers and practitioners in the area of conduct disorder/severe antisocial behaviour, and will include people with backgrounds in mental health, education, developmental psychology, and criminal justice” (p 31).

Under the Plan, existing services would transition to evidence-based, best-practice interventions, assisted by reporting on best practice by the expert group. Implementation would ensure that all three- to seven-year old children who require a comprehensive behavioural intervention (up to 5 per cent of children) would receive this level of intervention before they are eight years old.

“Effective for different ethnic and cultural groups”

The absence of a Māori lens was notable in the formative stages of the Plan, particularly given the over-representation of Māori children and youth in behavioural referrals and their increased likelihood of entering the youth-justice system (Durie 2005, quoted in Cherrington 2009). The challenges inherent in mainstream education, justice, and care and protection systems, combined with failures to deliver good outcomes for Māori children and youth, were well documented in key reports at the time. The following section describes how the initial authors of the Plan viewed the cultural considerations.

The Plan discussed characteristics of conduct-problem prevalence in terms of severity, age, gender and socio-economic factors, but not culture or ethnicity. It concluded with the statement: “New Zealand research suggests that Māori and Pacific males are more likely to have behavioural difficulties than non-Māori, though to a large extent this is likely to be a function of economic disadvantage” (Ministry of Social Development, 2007b, p 9), citing a publication from the Christchurch Health and Development Study.

Appendix 1 of the Plan, however, described a 2004 analysis of current behavioural services provided for children and young people, which showed their ethnicities as: New Zealand European 53.7 per cent, Māori 35.5 per cent, Pacific 4.6 per cent and other groups 6.2 per cent. There was no analysis of this data in Appendix 1, however a quick consideration shows that Māori children and youth comprised 35.5 per cent of the recipients of behavioural services – notably more than twice their population proportion of 14.7 per cent (Ministry of Social Development, 2007b). Despite this, as noted above, a socio-economic explanation was given.

The comparatively short discussion specifically on ethnic and cultural issues in the Plan (three sentences in total) sits under the principle of “effective for different ethnic and cultural groups”, and is focused on the intended transition to international, evidence-based programmes:

There is good international evidence on which programmes are likely to be effective in the management of conduct disorder/ severe antisocial behaviour. Some of these programmes have been successfully replicated for different ethnicities and in a number of different countries. Most of these programmes, however, have not yet been tested for their effectiveness in the New Zealand context. Any programmes selected for use in New Zealand must be shown to be effective for different cultural and ethnic groups, and agencies need to consider whether and how programmes can be supplemented to improve their effectiveness. (Ministry of Social Development, 2007a, p 28)

The importance of culturally competent delivery for Māori, Pacific peoples and others is noted in one sentence in a subsequent section of the Plan (p 50). These two references are the only considerations of ethnicity or culture in the Plan, and they illustrate the parched-desert characteristic mentioned earlier.

Establishing the external expert advisory group

The Plan’s proposed expert advisory group (the AGCP described above) was considered integral to the work programme, particularly in relation to the design, delivery and evaluation of services for three- to seven-year- olds. In view of the ethnicity data in Appendix 1, the composition of the AGCP was an opportunity to enact Treaty of Waitangi responsibilities and ensure mātauranga Māori was well represented.

Ministry of Social Development[2] – as lead in the interagency officials’ group meetings – discussed approaches to setting up the expert advisory group. The issue of Māori representation on the AGCP was discussed and some non-ministry officials advocated that appropriate Māori expertise should be included. Ministry officials felt a quicker, pragmatic approach could be achieved by shoulder-tapping existing contacts. To that end, the ministry decided to form the expert advisory group from the seven academics[3] who had previously advised on the Plan itself. As these academics were predominately New Zealand European males, the ministry invited a further five experts to the AGCP, including a Pacific paediatrician and a Māori consultant, the latter having recently undertaken work for the ministry and Child, Youth and Family in a related youth-justice area.

At its first meeting, the AGCP queried the adequacy of Māori representation – it noted that the work programme would be unachievable without an appropriate relationship with, and input from, Māori. Wayne Blissett, the sole Māori AGCP member, supported the need for more Māori expertise. However, ministry officials initially continued with the status quo. Subsequently, the AGCP – citing the Treaty – made a formal recommendation that a Māori advisory group be set up. As a result, Te Roopu Kaitiaki – which comprised seven Māori experts[4] – was established.

An attribute of the AGCP was its insistence on Treaty principles, which were premised at the beginning of all its reports. Despite providing a strong foundation for partnership, protection and participation, inclusion of Treaty principles alone did not set out a Māori understanding of behaviour. To address this gap, Te Roopu Kaitiaki commissioned work, undertaken by Lisa Cherrington (Ngāti Hine, Ngāpuhi) (2009), which was published as Te hohounga: Mai i te tirohanga Māori / The process of reconciliation: Towards a Māori view – The delivery of conduct problem services to Māori. Te Roopu Kaitiaki additionally provided te ao Māori content for the AGCP’s Conduct Problems Best Practice Report (AGCP, 2009); this enabled prevalence data relating to Māori to be considered. Te Roopu Kaitiaki also supported the international, evidence-based approach (due to the generalisability of components of the international evidence), and emphasised the importance of Indigenous knowledge for understanding and working with Māori children, youth and whānau. They state:

It is important that Māori knowledge is recognised as a layer of evidence and is considered as part of the entire evidence base around being responsive to Māori tamariki [children], taiohi [youth]and whānau experiencing conduct problems. (AGCP, 2009, p 41)

Te Roopu Kaitiaki provided principles and made policy recommendations for both generic and kaupapa Māori programmes, stating that:

A major investment is required to support the gathering and analysis of evidence from a Te Ao Māori context to sit as part of the evidence base in Aotearoa/New Zealand to fully inform the delivery of effective programmes for conduct problems. (AGCP, 2009, p 43)

Kaupapa Māori knowledge base and programmes

By 2010, the AGCP was moving forward with its next report. However, the need – highlighted by Te Roopu Kaitiaki’s recommendations that evidence from te ao Māori comprise part of the New Zealand evidence base – was still outstanding. Angus, the second author of this chapter, was approached to undertake a part of this work.

While Te Roopu Kaitiaki had made progress on creating space for kaupapa Māori approaches, the focus of the project continued to be on Western prevention-science methodology (AGCP, 2011). There was still a lot of work to do in making space for a shared understanding. In taking on the role of incorporating mātauranga Māori into the project, I, Angus, became a member of the AGCP, as well as Te Roopu Kaitiaki. While the AGCP had been central in prompting the establishment of Te Roopu Kaitiaki, AGCP members had their own allegiances to known ways of understanding and interpreting evidence. These ways of understanding the world were not easily shifted.

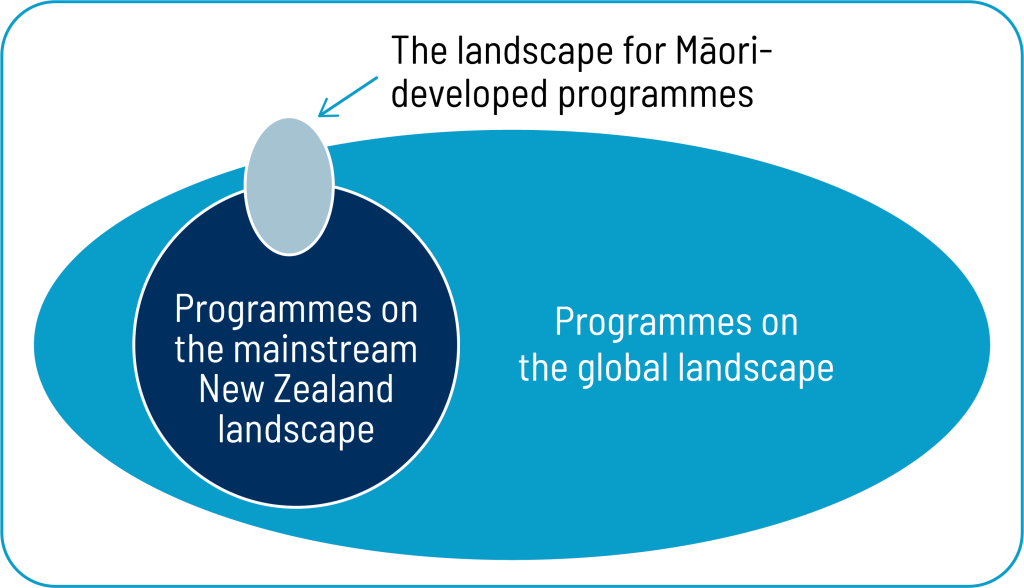

To address these differing worldviews, I put forward a series of propositions. First, a consideration of the research landscape. It was noted (and subsequently described in Chapter Four of the AGCP’s 2011 report) that global research into the development of effective interventions and programmes includes the landscape of pedagogy, curriculum, theoretical constructs and extensive research methodologies – usually enabled by generous resourcing. Such programmes in the mainstream New Zealand landscape, while not as wide ranging, bear similar characteristics. However, unlike their global counterparts, funding and research resources in New Zealand are comparatively limited. These problems of resourcing and recognition are further increased for Māori-developed programmes that strive to use a similar pathway; a mixture of success and failure is often experienced. Māori-developed programmes are almost always impeded by a lack of resourcing, and may be subject to criticism, for instance on questions of scientific validity, bases of evidence and narrowness of samples.

This situation is depicted in Figure 1.1 (replicated from AGCP, 2011). As part of Chapter Four, a stock-take of existing programmes and services that use a Māori platform was undertaken. I, Fiona, was made available to work with Angus, and particularly worked on collating data for the stocktake. Programmes and services that had the potential to address conduct problems in Māori children, youth and whānau – along with their associated publications and their status as emerging or sustained – were presented.

Second, issues in understanding evidence were explored, along with the reality of two research paradigms with differing assumptions and methodologies – Western science and kaupapa Māori. Māori research principles and the development of Indigenous knowledge systems were discussed. At the crux of these discussions was the challenge of defining what is meant by evidence, when one form of evidence is privileged above another.

Figure 1.1: An uneven playing field?

From AGCP, 2011 (p 46). Licensed for adaption and re-use under (CC-BY) 4.0.

The composition of the AGCP was very significant here and, with inadequate Māori membership, the discussions required relentless application by the few who supported a kaupapa Māori approach. I, Angus, provided a workshop on Māori worldview perspectives to the AGCP – to advance thinking and theorising and facilitate greater understanding of mātauranga Māori. I was often the lone Māori voice at meetings, which was at times very challenging and caused me a great deal of frustration. This led me to ask the other members of the group to consider this question: “What would the conversations be like if we were having them on a marae (Māori meeting house)?” At stake in the discussions was both the integrity of mātauranga Māori and the challenge of bringing a group of influential New Zealand social scientists to see that Western science is exactly that – Western.

Third, the importance of both streams of knowledge emerged. Throughout discussions, Te Roopū Kaitiaki emphasised the relevance of both knowledge streams. While programmes involving Māori need to be developed and evaluated from a Māori perspective, attention also needs to be given to the knowledge and insights gained from Western-science based evaluations. Consideration of the ways in which Western science and kaupapa Māori research can be combined to produce consensual decisions about programme effectiveness gives augmented value. The case was being made for a “blended schema”:

one that respects and acknowledges how both forms of evidence (western and indigenous) can help. […] Effective clinical practice with Māori whānau occurs best where both knowledge bases are cherished and where there is a crossing of cultural borders and the braiding of rivers. With this approach, the mana of the child, the inclusion of the whānau, and the integrity of the professional are all valued.” (AGCP, 2011, p 61)

The blended approach had been signalled in earlier literature (Durie, 2005; Macfarlane, 2008), with Durie citing the need to:

Harness the energy from two systems of understanding in order to create new knowledge that can be used to advance understanding in two worlds. (p 306)

He Awa Whiria: A Braided River

The model that responded to this need for a blended schema was He Awa Whiria: A Braided River. The braided river metaphor had been presented earlier but had not yet been applied in a practical context. In 2009, a foundational Collaborative Action and Research Network (CARN) symposium was held in New Zealand, at which I, Angus, presented the keynote address. I promoted a collaborative approach of blending practices of action research and kaupapa Māori research principles, using a braided river to illustrate this. A braided river became the metaphor that subsequently dominated the symposium’s proceedings (Davis et al., 2009).

In the conduct-problems project, He Awa Whiria was presented in a very practical context. Lists of conduct-problem interventions were tabled, and associated Western-science evidence and kaupapa Māori evidence were described – and it was here that the impact of the model began to be felt. In the AGCP setting, He Awa Whiria provided a compelling means of giving credence to differing epistemologies: that knowledge streams are able to braid in and out of one another, while recognising the uniqueness and value of each. One way of knowing is not privileged over the other; there is space for distinct streams of knowledge to be valued in their own right rather than assimilated. Furthermore, there is the potential to create new knowledge at the points where two knowledge streams converge and diverge.

Reception and influence

The series of propositions described above became Chapter Four of Conduct Problems: Effective services for 8–12-year-olds (the AGCP’s 2011 report) and the seminal publication of He Awa Whiria. The impact of the chapter was profound in that it introduced a new way of conceptualising knowledge streams. While the AGCP report presenting He Awa Whiria was not formally published until 2011, content was circulating among academics in New Zealand in 2010. In 2011, a report from the Prime Minster’s Chief Science Advisor, Improving the Transition: Reducing social and psychological morbidity during adolescence (Prime Minister’s Science Advisory Committee, 2011) was released. In the penultimate chapter of that report, the Chief Science Advisor’s authors quote at length from Chapter Four of the AGCP’s 2011 Report, then state:

It is the consensus position of this report that Western Science and Kaupapa Māori perspectives should not be seen in tension, rather an approach which encourages partnership and cooperation between these perspectives should be taken. (Prime Minister’s Science Advisory Committee, 2011, p 294)

They then present the He Awa Whiria model, describing it as a “promising solution to encouraging an appropriate partnership between Western Science and Kaupapa Māori” (Prime Minister’s Science Advisory Committee, 2011, p 296).

In conclusion, we share a reflection on what occurred in the conduct-problems project. Over two years, a government policy plan (Ministry of Social Development, 2007a) based on a Western approach to international evidence shifted to understanding that programmes based on mātauranga Māori were a valid and necessary part of policy plans for New Zealand. First, for government officials, this shift included coming to an understanding of the significance of the Treaty. Second, a group of influential members of the AGCP began to accept the validity of other forms of knowledge, specifically mātauranga Māori. They came to an agreed position on this in the publishing of their report, which used the He Awa Whiria framework for the first time. Third, a wider group of social scientists, writing for the Prime Minister’s Science Advisory Committee, recognised the power of He Awa Whiria for understanding evidence and finding a way forward in addressing challenges in New Zealand. This promoted the framework for wider use. Back at the Ministry – over time and under the framework’s growing influence – describing He Awa Whiria became a means to communicate the new understanding of multiple streams of evidence and/or balancing policy considerations.

The parched desert was gone. In its place was He Awa Whiria, a braided river, preserving mana, promoting wellbeing, and bringing growth and the opportunity to flourish for all.

References

Advisory Group on Conduct Problems (2009), Conduct Problems Best Practice Report, Ministry of Social Development.

Advisory Group on Conduct Problems (2011), Conduct Problems: Effective programmes for 8–12-year-olds, Ministry of Social Development.

Cherrington, L. (2009), Te hohounga: Mai i te tirohanga Māori | The process of reconciliation: Towards a Māori view – The delivery of conduct problem services to Māori, Ministry of Social Development.

Davis, N., Fletcher, J., Groundwater-Smith, S. & Macfarlane, A. (2009), The Puzzles of Practice: Initiating a collaborative action and research culture within and beyond New Zealand (paper about conference), NZARE Conference and Annual Meeting, Rotorua, New Zealand: https://ir.canterbury.ac.nz/handle/10092/3475

Durie, M.H. (2005), Whānau as an Intervention Strategy for Conduct Problems, paper presented at Severe Conduct Disorder Conference, Wellington.

Macfarlane, A.H. (2008), ‘Kia Hiwa Rā! Listen to Culture: A counter narrative to standard assessment practices in psychology’, The Bulletin, 111, 30–36.

Ministry of Social Development (2007a), Inter-agency Plan for Conduct Disorder/ Severe Antisocial Behaviour 2007–2012, Ministry of Social Development.

Ministry of Social Development (2007b), The 2007 Social Report: https://socialreport.msd.govt.nz/2007/index.html

Prime Minister’s Science Advisory Committee (2011), Improving the Transition: Reducing social and psychological morbidity during adolescence. A report from the Prime Minister’s Chief Science Advisor, Department of the Prime Minister and Cabinet.

- Intense discussion on terminology eventually contracted the unwieldy phrase ‘Conduct Disorder/ Severe Antisocial Behaviour’ to ‘Conduct Problems’, and the expert advisory group was established as the Advisory Group on Conduct Problems. ↵

- The authors wish to make clear that commentary on Ministry of Social Development actions in this project relate specifically to an earlier era (2007 to 2008) and we acknowledge and celebrate the transformation in leadership that draws from te ao Māori demonstrated by the ministry since that era. This transformation is illustrated in chapters 4 and 10 in this book. ↵

- See acknowledgements inside the front cover of the Plan. ↵

- Te Roopu Kaitiaki compromised: Wayne Blissett (Ngāpuhi), consultant, Yesterday, Today & TomorrowLtd; Dr. Angus MacFarlane (Ngāti Whakaue, Ngāti Rangiwewehi), associate professor, University of Waikato; Whaea Moe Milne (Ngāti Hine, Ngāpuhi-Nui-Tonu), consultant; Materoa Mar (Ngāpuhi, Ngāti Whātua and Ngati Porou), director, Yesterday, Today & Tomorrow Ltd; Dr. Hinemoa Elder (Ngāti Kuri, Te Aupouri, Te Rarawa and Ngāpuhi), Child and Adolescent psychiatrist, Counties Manukau District Health Board; Mere Berryman (Ngāi Tūhoe, Ngāti Awa, Ngāti Whare), manager, Poutama Pounamu Educational Research Centre; Peta Ruha (Ngāti Awa), programme manager, Lower North Severe Conduct Disorder Programme. ↵