12 He Rangahau Whiria:

A research methodology for both parties to the Treaty of Waitangi

Dr. Fiona Cram and Henry Lyons

Introduction

The land is our father; the land is our chieftainship; we will not give it up.

Makoare Taonui, 12 February 1840 (quoted in Buick, 2020, p 124)

As the founding agreement of Aotearoa New Zealand, the Treaty of Waitangi, signed by Māori and the British Crown in 1840, speaks to a relationship between Māori as tangata whenua (Indigenous people of the land) and newcomers as tangata Tiriti (non-Māori partners to the Treaty). The guidance provided by the Treaty for how we can live together in Aotearoa New Zealand, on land where Māori are the traditional custodians, reverberates within the research world. Authentic research relationships between Maori and non-Maori research communities require that the knowledge and ways of knowing that people have within their worldview be recognised and valued. He Awa Whiria is a framework that explicitly draws on people’s expertise, inquiry paradigms and life-worlds, to nurture transdisciplinary ecologies in which everyone has something to share and something to learn. The framework also allows for new understandings to be generated, within a relational context. Drawing on this framework, He Rangahau Whiria (braided research) responds to the questions of those starting out on their research journey: questions about where to begin, how to go about their journey, and how to remain feeling both courageous and safe.

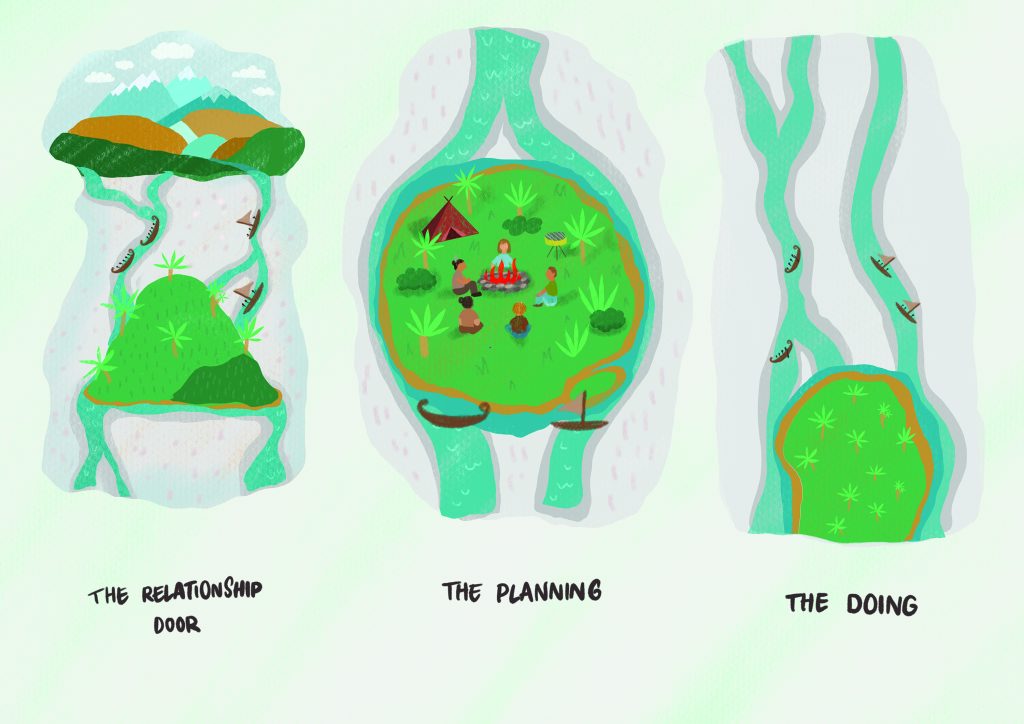

To set the scene for this discussion, we begin with a brief recap of the Treaty. This is followed by a discussion of why we should braid knowledge and how He Awa Whiria enables us to do this. The three steps of He Rangahau Whiria – the relationship door, planning and doing – are then described. Following this, the potential of research, which realises the Treaty dividend, is discussed, and some concluding comments are made.

The Treaty of Waitangi

The Treaty of Waitangi, the founding document of Aotearoa New Zealand, was first signed at Waitangi on 6 February 1840 by Māori chiefs and British officials. As with He Whakaputanga o te Rangatiratanga o Nu Tirene: the Declaration of Independence of the United Tribes of New Zealand, signed by Māori chiefs in 1835, the Treaty is an affirmation of tino rangatiratanga: namely, Māori independence and sovereignty. This denotes not only possession, but also control and management of lands, dwelling places and other taonga (treasured cultural possessions) (Orange, 1987; Waitangi Tribunal, 1995). Māori expected the Treaty to be honoured, and that they would remain physically and politically in control of Aotearoa New Zealand and their destiny.

We are fast approaching the two-century mark since the signing of the Treaty. The majority of the intervening years have been marked by Crown insistence that Māori are not sovereign peoples and that Māori become more like the people they had initially welcomed to the shores of Aotearoa New Zealand. Māori resistance to these efforts has been unceasing. Māori have pressed on in the knowledge that they are a sovereign people, albeit people impacted by disease, warfare, land confiscations and thefts, and structural problems (for example, poverty, health disparities) often being perceived as resulting from Māori personal deficits (Reid and Cram, 2004). Until recently, research conducted by non-Māori often helped to justify and rationalise these assaults, especially the calls for Māori to change because they were found to be ‘wanting’ in comparison to Western colonial norms (Smith, 1992).

Māori now live in two lands. In one land – Aotearoa – Māori remain tangata māori, or ordinary people (Moewaka Barnes, 2000). Within many Māori gatherings, and in places where Māori customs and practices are the norm, Māori knowledge and ways of knowing are accepted and validated. Within this Aotearoa, a positive discourse around Māori values and beliefs exists. It is not unusual to hear Māori talk about the comfort and safety they are able to find in Māori situations where they do not have to explain what being Māori is about and why being Māori is okay – because everyone knows. (This is not to be dismissive of other issues and tensions that exist within these fora.) Sometimes non-Māori are present in Aotearoa because they have married a Māori person, have Māori children or grandchildren, or because they feel at home there.

The other land – New Zealand – is where most non-Māori live and where Māori often go to attend mainstream education institutions, to gain employment, and to receive healthcare and wellbeing assistance. Many Māori occupy this place more-or-less permanently and have become accustomed to it, whereas, for others, it is like a pair of ill-fitting shoes that are hurriedly pushed off upon return to Aotearoa. In New Zealand, the dominant discourse about being Māori is not positive; rather, it is informed by colonial processes rooted in Darwinian notions that Māori are less than non-Māori. Yet, as Dewes (1968, reproduced in Salient, 1972, p 11) explains, there is more to being Māori than this mainstream view: “I am sick and tired of hearing my people blamed for their educational and social shortcomings, their limitations highlighted and their obvious strengths of being privileged New Zealanders in being bilingual and bicultural ignored.”

The link between research, power and resources has been made by many Māori researchers (for example, Te Awekotuku, 1991; Waipara-Panapa, 1995). Knowledge is not power; rather, being able to define what is acceptable knowledge is power. The dominance of Western history and culture means that Māori forms of knowledge and ways of knowing are often seen to lack ‘mainstream’ legitimacy, being positioned as ‘nonscientific’ and ‘other’ (Waipara-Panapa, 1995). The challenge for Māori researchers has been to gain insight into both these lands – Aotearoa and New Zealand – in the knowledge that “the Treaty reaffirmed our right to develop the processes of research which are appropriate for our people … sourced in tikanga, philosophies and the ideas of who we are” (Jackson, 1996, pp 8–9). Kaupapa Māori research is an attempt to retrieve space for Māori voices and perspectives, methodologies and analyses, whereby Māori realities and knowledge are seen as legitimate. This means centring te ao Māori (Pihama, 1993). An integral part of kaupapa Māori research is also the critique of mainstream societal understandings of what it is to be Māori (Smith, 2012). Kaupapa Māori research therefore seeks to displace oppressive knowledge through a structural analysis of the societal barriers (for example, racism, colonialism) to Māori flourishing as Māori. In doing so, Māori researchers are aware that the colonial society in which they reside is not a passive entity. The promotion of Māori interests that are strengths focused, rather than deficit based, will undoubtedly encounter political, economic and cultural backlash. This is because what Māori researchers are attempting to do is reclaim the Aotearoa New Zealand that is envisaged in the Treaty and reposition Māori as sovereign peoples within this land.

What of non-Māori in this scheme? The sharing of Aotearoa and its resources was acceptable to Māori. What was needed to facilitate this sharing was a constitutional code that would “articulate rights and responsibilities, regulate behaviours, and accommodate access rights of settlers without compromising the guardianship/ownership rights of Māori” (Mead, 1999, p 28). The Treaty is this code and the signing of it created this nation; “If Pakeha have a legitimate right to be in this country there is no question that the Treaty is the source of that right because the Treaty is the bargain struck by the Crown … with the sovereign people of Aotearoa” (McCreanor, 1989, p 36). However, the dominance of a Western-imperialist inquiry paradigm in much of the research conducted by Pākehā has meant that the ‘universal’ knowledge generated conceals issues of colonial power, privilege and the violent means used to establish a country that is in breach of its Treaty obligations.

For many Pākehā, this land is ‘New Zealand’ and it is monocultural. It is a place of normality and comfort where the privilege and power of being able to shape mainstream history, identity, and definitions of what New Zealand was and is lies with Pākehā. Colonisation is primarily responsible for this imbalance; it affords Pākehā ‘historical privilege’ and the benefit of structural advantages over time and across generations, through the transfer of wealth, power, social position and status (Borrell et al., 2018). In this land of New Zealand, Aotearoa is just a name, and a name that many Pākehā only seem comfortable engaging with at a surface level. The Western cultural approach that promotes explainability and needing to know what things mean can, in some cases, limit the capacity of many Pākehā to see past words and to comprehend te ao Māori. Instead, their focus has remained superficial. There has been extensive fixation on, and often trivial deliberation over, the origins and meaning of the word Aotearoa and the accuracies of Māori histories (Belich, 1996; King, 2003), which have only served to fuel the discourse of Māori inferiority.

For many Pākehā, the relationship with Aotearoa is transactional and resembles that of a fashionable clothing brand, with items Pākehā can try on for style and return to the shelf should the fit not be right. As Jones (2021) outlines, te reo Māori is one such ‘jacket’ which some Pākehā are only too happy to try on at this moment in time. Just like the land, the language has been graciously shared by Māori. But the promise of revitalisation comes with the risk of Pākehā acquisition. This relationship with Aotearoa is built upon a self-serving ‘standard story’ of Māori/Pākehā relations (McCreanor, 2009), a ‘master narrative’ that privileges Pākehā ways of knowing and doing, Pākehā-based designations for what is remembered and forgotten, and what is silenced and heard (Borell et al., 2018). As a country, in the 1970s and 1980s, Aotearoa New Zealanders began a “reluctant search for ourselves” (Williams, 2022). If this quest is to continue productively, many Pākehā must confront their historical privilege, and embrace the potential for relational knowing that exists below the surface – beyond names and words.

In the present day, some Pākehā choose to wear ‘Aotearoa’ as a political action – adorning social media pages, research papers and statements of identification with the term ‘Aotearoa New Zealand’ – as a superficial nod of recognition to those whose land they are on. Where research is concerned, there is a genuine opportunity to go beyond this, to remove the layers, and to reconcile and shape identity. To do so requires a commitment to anti-oppressive research in which:

… knowledge does not exist ‘out there’ to be discovered. Rather, knowledge is produced through the interactions of people, and as all people are socially and politically located (in their race, gender, ability, class identities, and so on), with biases, privileges, and differing entitlements, so too is the knowledge that is produced socially located and political. (Potts and Brown, 2005, p 19)

Justice Joe Williams (2022) critiques the “historical amnesia” that has afflicted successive governments with an ongoing capacity to ‘forget’ the lessons learned from partnership building, which has contributed to a cycle of “social unravelling”. The Treaty transcends the formal Crown– Māori partnership realm; research is the territory in which – through partnerships and relationships – the social fabric of all Aotearoa New Zealand can be woven and strengthened.

There is a need for Pākehā researchers to be critically self-reflective about their preconceptions, values and priorities, and the impact of these on the design, conduct and interpretation of research. By this, we mean that researchers need, as a minimum, to be aware of the assumptions, ideologies and power relations that underpin and legitimate their modus operandi in research. The rise in inquiry paradigms and methodologies that demand this reflexivity (for example, feminist research, transformative research) means that more and more Pākehā researchers have shown themselves capable of gaining a window on their worldview. This, in turn, enables Pākehā researchers to enter into dialogue with Māori about how their knowledge and ways of knowing can also challenge a colonial status quo. Together, Pākehā and Māori can seek an Aotearoa that upholds Māori sovereignty in the context of the manaaki (hospitality) that was extended to newcomers in the Treaty.

The process of navigating the spatial boundaries afforded by kaupapa Māori can be an uncomfortable experience for some Pākehā researchers. Western ways of knowing are no longer at the centre of everything and this can produce feelings of alienation and incapacitation for some Pākehā, who – by default of their cultural standing – are so often used to being in control of research and of knowing where they belong in the mix. This can lead to what Tolich (2002) terms “Pākehā paralysis” – that is, the inability of some Pākehā researchers to distinguish their role in Māori-centred research from their business-as-usual dominant research paradigm. Pākehā paralysis can hamper Pākehā researcher agency and, as Hotere-Barnes (2015, p 42) outlines, this can lead to immobility, to the extent that expertise and resources are held back, or – at worst – avoidance altogether, an opting out because “it’s too difficult and not my problem”.

The journey of critical self-reflection can be tormenting, as much as it is enlightening, and this can compound the Pākehā-paralysis phenomenon. Rather than fixate on the paralysis, Pākehā researchers can view kaupapa Māori as an impetus to do better research and harness daunting feelings as energy for growth. As Fabish (2014, p 35) highlights, kaupapa Māori can be “an invitation to radically rethink the way we do research”; here, “subtle learning” is experienced through engagement and “the feelings of awkwardness” which can come from “being decentred” and “culturally deskilled” in the process. Research in Aotearoa is not just about the discovery of new and valuable information. It is an opportunity to connect responsibly, to forge relationships, and evolve identities together. Kaupapa Māori does not need to work to accommodate challenges faced by Pākehā, but rather, Pākehā can establish their boundaries and space through being informed and guided by kaupapa Māori. Kaupapa Māori can hold space for Māori, and at the same time, become a beacon and an effective tool for Pākehā to better meet their guest responsibilities with respect to the Treaty.

He Awa Whiria

Many people from Aotearoa New Zealand will recognise the Rakaia River in Canterbury (see Figure 12.1). Who wouldn’t be tempted to use the beauty of this awa (river) as a metaphor to inform research inquiry and provide a place to talk to one another in ways that uphold the tenets of the Treaty? This metaphor, gifted by Professor Angus Macfarlane and Associate Professor Sonja Macfarlane, is an inquiry methodology that recognises the often-separate journeys taken by mātauranga Māori and Western knowledge systems. It acknowledges that our knowing does not stand still, but rather, flows forward as it is fed by new waters at the source and as it is joined by tributaries. He Awa Whiria highlights the importance of the times when we, as Māori and non-Māori researchers, come together to examine our shared context. As the A Better Start National Science Challenge (2015, p 16) stipulates, this mixing and mingling of knowledge systems can potentially “create new knowledge that can be used to advance understandings in two worlds”. This is fitting, as the alluvial islands that separate channels in a braided river are often places that have a unique ecology. If we are to cultivate these places in a research context, we need to have our eyes open to their ephemeral nature and the parallels between their physical properties and the life of entwined knowledge streams. The unique ecologies that come to exist on alluvial islands are fragile; they are susceptible to disappearing just as quickly as they appear. Like knowledge, these islands are in a constant state of flux, moving and changing shape as river flows are fed by tributaries and respond to rainfall in distant places.

Figure 12.1: Rakaia River, Canterbury, Te Waipounamu

Tracey McNamara @iStockphoto.com. Used under licence.

As a metaphor for research, it is essential to foster such unique ecologies as they are places where we will find out how we can move into the future together as parties to the Treaty. We therefore need research methodologies that encourage dialogue, that facilitate transdisciplinary interactions, and that enable us to integrate knowledge, so that all are enlightened. The use of the term ‘integration’ here signals that there should be “unrestricted and equal association” between knowledge streams, rather than the mere search for similarity or difference, or mātauranga Māori and Western knowledge being “blended or synthesised” (Berkes, 2009, p 154). Integration, as it is used here, honours Māori self-determination and creates a context for two worldviews (Māori and Western) having a dialogue, rather than “jagged worldviews colliding” (Little Bear, 2000). Integration is also an acknowledgement that no one’s knowledge is static; rather, knowledge evolves through processes that include investigation, experimentation, contemplation and inspiration (Brant Castellano, 2004).

The He Awa Whiria framework has been widely discussed in a number of research contexts. The Advisory Group on Conduct Problems (2013) showcased the He Awa Whiria framework, noting that the distinctiveness of two knowledge streams (prevention science and kaupapa Māori) were both able to inform the development of kaupapa Māori programmes, as well as the evaluation of programmes (in either stream). Paki and Peters (2015) describe how the braided river metaphor enabled them to contemplate how to merge spaces – each with their own unique history – to study children’s learning journeys from early childhood to school. Berman et al. were somewhat more circumspect about the integration of knowledge systems; they describe the support of Dr. Rarawa Kohere in helping them develop a tohu (symbol) for their “journey of grappling with conflicting worldviews”. They are clear that, as a team, they “draw on Māori ways of seeing to filter Western discipline knowledge and actively and critically consider compatibility” (2015, p 104). Ramstad and Faulkner (2008, p 252) noted that their hui (meeting) between Māori and non-Māori scientists was “not without conflict and tension”; the implication was that this hui process was pivotal as a forum for working through contentious issues. Smith and colleagues (2013) likewise describe the interface of Western science and mātauranga Māori as negotiated space, requiring acknowledgement and respect for differing worldviews.

In 2018, researchers Min Vette (Oranga Tamakiri – Ministry for Children), Moira Wilson (Ministry of Social Development) and Fiona Cram (a co-author of this chapter) spent time in wānanga (focused deliberation), thinking about how to understand the Māori outcomes from a retrospective impact evaluation of the Oranga Tamariki Family Start programme. This evaluation looked at outcomes for children born from 2004 to 2011. It compared the outcomes, in administrative data, for children in whānau who were enrolled in Family Start with the outcomes of those whose whānau were not enrolled but who would have been if Family Start had been offered in their region. He Awa Whiria provided a methodology to guide inquiry, enabling the team to explicitly explore how Māori and Western knowledge systems could be braided to inform their understanding. The team also conceptualised He Awa Whiria as flowing towards and into the sea, which is “symbolic of a progression towards a multitude of opportunities and perspectives represented by the expanse of the ocean” (Cram et al., 2018, p 168).

The sixth report of the Family Violence Death Review Committee (FVDRC) (2020) also called upon different knowledge streams to consider the missed opportunities to disrupt the life course of men who perpetrate family violence. The FVDRC considered the historical and ongoing impacts of colonisation; for the committee, this included the unequal burden of intergenerational trauma shouldered by Māori men and the impacts of unchecked coloniser privilege on Pākehā men. Walker (2015) claims that our high tolerance for violence as a nation can be attributed to these impacts of colonisation. He writes that “the psyche of both Pākehā and Māori is scarred by colonisation” (p 48). We suggest that, for some Pākehā men, this means the burden of their colonial forebears’ social isolation and loneliness, drunkenness and interpersonal conflict – all experienced within the context of the cultural baggage they packed for their trip to Aotearoa New Zealand. The FVDRC used He Awa Whiria to frame understandings of the impact of colonisation. Using He Awa Whiria enabled the FVDRC to make explicit the relationship between interpersonal and structural violence, and to discuss how men who perpetrate family violence are caught up in something bigger than themselves. This provided a starting point for recommending interventions that focus on healthy masculine norms that reconnect men with supports that can heal and restore, and that engage whānau and communities in men’s positive change journeys. The integration achieved through He Awa Whiria was that men can be good partners and fathers who contribute to the wellbeing of their whānau.

The examples above are just a small sampling of the ways in which He Awa Whiria has proven to be a productive way to blend and integrate knowledge streams, and of how, in particular, Māori and Pākehā knowledge streams can speak to one another in ways that create alluvial islands of new knowledge ecosystems. However, our view is that something is missing in the ‘instructions’ for braiding; namely, how do those holding separate knowledge strands undertake a journey together that honours the Treaty and respects what people have come to share? In addition, how can these two parties be encouraged to also be learners in a transdisciplinary context, where the aim is whitiwhiti kōrero (dialogue) that leads to the development of mutual thinking (Te Hennepe, 1993)? How do people come to know and to trust one another, and commit to growing, learning and taking action together? It is with these questions in mind that we next describe a three-step training programme, He Rangahau Whiria, in which knowledge-strand holders are encouraged to enter into a relational space that lays the foundation for planning research together. As relationships grow and are strengthened – and undoubtedly tested during planning – those involved are then encouraged to take heart, seize courage and trust in relationships, so they can progress the research. This may be challenging at times, and, if it is, it will be what Dr. Irihapeti Ramsden would have described as a ‘teaching moment’ – where ‘challenges’ do not rock relationships but, rather, send people back to discuss, plan and give it another go.

He Rangahau Whiria

He Rangahau Whiria is a three-step instruction about how to move into He Awa Whiria (see Figure 12.2). It emerged from the authors’ sharing of their respective experiences of connecting and working with people and communities during their research. These discussions highlighted the importance of relationships and of people being able to have input into the planning and implementation of research.

He Rangahau Whiria is presented here as a contemplation of the things the authors have learned that may be helpful to others – to those wanting to explore their expertise and share in the expertise that others have, to those wanting to generate new understandings and ways of undertaking research that is Treaty-centred. Each step begins with a short introduction, followed by two columns of considerations and advice from each of us: Henry’s from a Pākehā worldview and Fiona’s from a Māori worldview.

Figure 12.2: The relationship door

Illustration by Kophie Su’a-Hulsbosch

At a hui a few years ago, Māori health providers were asked about their theory of change: What laid the foundation for their work with Māori that then resulted in initial changes, followed by more long-term changes? Much discussion ensued and their final theory of change emerged: whanaungatanga (building relationships) leads to whanaungatanga, leads to whanaungatanga. In other words, relationship building leads to strengthened relationships which, in turn, lead to strengthened relationships. A Māori world is all about relationships – where people are from, who they are related to, who they know. In a Pākehā world, this might be called a network or community. Both worlds stress the importance of connectedness and, in Aotearoa New Zealand, we are lucky to be able to do this across ethnic boundaries: finding the people, experiences, values and love of place that connect us to one another.

| Henry | Fiona |

|---|---|

| • Be prepared to step out into the relational space where there is no methodology. It’s uncertain, you won’t have control, and there are ways of approaching things that might feel secure and homely but you need to let go of them. • A relationship is more than a partnership. Stepping into the relational space starts a process of connection that transcends temporality. Partnerships are arrangements that can be started and finished; relationships go forever. • Reflect and situate yourself. You cannot exist objectively in the relational space, or freely detach from and reattach yourself to a relationship. Your past, present and future are located within the connection to which you must be accountable at all times. This requires you to constantly reflect and work with a sense of responsibility for all people involved. • Connection and knowledge are going to come to you through doing. This is not something you can learn prior. Facts, information and skills you acquire before stepping into the relational space can offer you some helpful context, however, these alone do not predetermine your capacity to connect or the extent of what you can know. Fronting up, being vulnerable, committing yourself and working together will give you this. • The relational space does not revolve around you. The process of doing requires you to de- centre yourself and shift from being in control to being a contributor. It is not going to work if your motivation for ‘doing’ is guided by some preconceived outcome you have. You need to think about what you can offer to nurture the space and connection. |

• Aroha ki te tangata – A love for the people. Sharing connections about people and place is a normal part of coming together in a Māori context. Welcomes are invariably followed up by whakawhanaungatanga (building relationships) – in this context, sharing about our people, our places and our whānau – so that those who are present can establish kinship connections. • The current fashion is for non-Māori to learn their pepeha (tribal introduction) and describe their ancestry and their connection with Aotearoa – what mountain provides them with shelter, what river nurtures them. This is not a rite of passage; it is the start of a kinship-like relationship, whereby non-Māori accomplices begin to become ‘like whānau’. • When we contemplate kinship relationships, we are thinking about shared understandings and values, about roles and responsibilities, and about how we fulfil our obligations to one another. This ‘accounting’ system can mean the fulfilment of instant reciprocity, through to intergenerational obligations. • He kanohi kitea – Being a face that is known. When we stand to share our pepeha, we are also showing our face, so that people come to know us. There is a lot of information about our whakapapa held in our faces, in our non- verbals, in the way we move, et cetera. Being personally present enables people to take this all in. Having a cup of tea and a break after people have introduced themselves allows people to mix and mingle, to catch up with those they have not seen for a while and to connect with new people whose pepeha has sparked their interest or a potential connection. At one hui, people introduced themselves and described a favourite place, a place that nurtured them when they visited in person or in their memories. This provided pathways for many connections to be made over a cup of tea. |

The planning

Planning for connectedness in He Rangahau Whiria is about planning to move at the speed of trust and finding adequate cushioning to facilitate a smooth ride in the process. Agenda, egos and titles need to be left at the door, and subsumed by the greater connection. Be prepared for some bumps along the way and to feel uncomfortable at times. Some cushioning can come in the form of an understanding of the fundamental differences between Western and Māori worldviews. Consider the nature of relationships beyond person to person: for example, the inherent differences in the prevailing ways Māori (intrinsic/collective and all encompassing) and Pākehā (separate/individual property rights) connect to land.

| Henry | Fiona |

|---|---|

| • Know yourself and the land you’re on. It is important to think about where you come from and how you benefit from settler colonialism and historical privilege. Think about your connection to the land you live and work on, and your relationship with the people whose land you’re on. • Know why you are doing what you are doing. Think deeply about the reasons that sit behind what you are planning to do. The catalyst for embarking on a journey grounded in connection needs to be a motivation for collective good rather than self-interest. • Be guided by trust. Trust, rather than time, is the focal point of the continuation of a relationship. Trust cannot be planned for or acquired; it is an earned manifestation of shared experience. The level of trust will ultimately set the pace for you. • Your skills are just talents that might be useful. These attributes do not define who you are or act on your behalf. The relationships you make, as well as your capacity to respect and collaborate, will do this for you. Your expertise are koha (gifts of thanks). • Know how to take guidance and wait to be asked. Every context is different and there will always be unique dynamics within groups and communities. There is no one-size-fits-all tool for interpretation of the unknown. Be patient, feel things out, and be open to letting people help you to navigate this. |

• Titiro, whakarongo … kōrero – Look, listen … then speak. It pays not to make assumptions about the people, the place or the kaupapa (agenda). If people are new to any of these, then a good guide is to take a back seat and absorb what is going on, to become acquainted with the context. Speaking can then happen by invitation or when a sense is gained of what contribution is needed from you. • Kia tūpato – Be careful. Being careful is about treading lightly in a context that you should gain some knowledge about before you arrive. Consider using the internet to look for information about the place, people and kaupapa, so you are a little prepared for what you are stepping into, and also have a chance beforehand to consider if you are the right person and what you might take to share (and perhaps also whether you need to be accompanied by someone who can guide you). • Kia māhaki – Be humble. Remember that you will be one of many experts in a room full of people who have something to share and also something to learn that they will take away with them in their kete (basket). Think about how you might share with others – the language you will use, how you will package information, the resources that you might leave with people. If you spark people’s interest, then your sharing will be well directed by their questioning and discussion. |

The doing

‘The doing’ in He Rangahau Whiria is about finding your feet and learning as you go. The doing is the place where connection is forged, meaning is discovered and new knowledge grounds its roots. At a series of hui focused on te ao Māori, ‘wānanga’ was described as timeless energy and the disappearance of time in space and interaction. Those present were moved by and connected with the description, with exclamations of “Ah, now I get it … I thought it meant ‘lesson’”. This example reflects the level of meaning that can be attained through doing, where words can take on a deeper meaning, born from the experience of doing rather than the pages of a dictionary.

| Henry | Fiona |

|---|---|

| • Let go, be genuine and calm. Trust is having confidence in the unknown, and letting go can be a first step toward this. Being true to yourself, accepting imperfection and that things might not always go to plan, allows connection to grow and flourish. • Get comfortable with the feeling of discomfort. If you are feeling a sense of discomfort, then this is probably a good thing – because it means that you care. Reflection can be a catalyst for discomfort; moving toward a place of comfort is the antidote to paralysis. • Let the experience guide how you find your place. Shared moments and getting to know one another will position you. There is no framework or protocol document you can read up on that is going to walk itself off the PDF pages and tell you when to get up and open a door for someone, or when it is right to reach out and hold someone’s hand as an offer of support. A Pākehā researcher in a remote, rural community was encouraged to enter a pool competition at the local pub and was soundly beaten in the first round by a kuia (female elder). Quips made in the moment kickstarted a friendship, the offer of a place to stay upon return and introductions to people to interview in the community. • Consider inclusion as a sign that it’s going well. Being and feeling included, and finding yourself in enriching, unfamiliar situations is a gift born from connection and of the relationship. It is pure and unforced. Getting to this place requires you to go with the flow of the experience. |

• Kaua e takahia te mana o te tangata – Do not trample on the mana of the people. When implementing a plan that requires engagement with people, put them at the centre and let them lead the inquiry. Again, don’t make assumptions about people; start with an affirming inquiry that speaks to the wealth of knowledge they can share with you. When a Māori researcher went to a small, marginalised community to interview a koroua (male elder), he spent the first visit hiding in his car, as there was an armed-offender call out. At the next visit, the researcher’s first question for the koroua was about what he liked about living in his community. The koroua nearly fell off his chair and was delighted enough with the approach taken that he networked the researcher with other residents he could interview. • Manaaki ki te tangata – Be a generous host. Remember that people whom you involve in your ‘doing’ are giving up their time to sit with you, and sharing their knowledge and expertise with you. • Seek advice about what you should take with you, what is polite for them and what you should leave them with as a koha. When interviewing a kuia (female elder), a Māori researcher knocked on her front door. The kuia called out to come in and the researcher entered, with apologies for not finding the back door, and then waited to be guided as to where they should sit. The researcher brought kai (food) for the kuia and gave her a monetary gift when they left. |

Discussion

The integration of mātauranga Māori and Western knowledge streams is not about the assimilation of mātauranga Māori into pre-existing Western research methodologies, or about merely adding a Māori perspective (Coombes, 2007). Rather, it is the next conversation, one that follows on from the discourse of the past three decades of Māori providing non-Māori researchers with advice, protocols and checklists of how to engage with community-based Māori knowledge holders (Cram et al., 2002). While these protocols have brought about new, more considerate and respectful approaches to Māori communities by non-Māori researchers, there has been, across the last 20 to 30 years, a growing investment in the capability of Māori researchers. As a result, Māori academics are indigenising research and turning the “bogeyman of ‘otherness’”, created by many years of scientific objectification of Indigenous peoples and their knowledge about the world, on its head (World Health Organization, 1996, p 10). We now have more opportunities than ever to integrate mātauranga Māori and Western knowledge streams, to find solutions to some of the problems facing our world. Mead (2003, p 318) provides a Māori view of integration that involves: te hōhonutanga – an in-depth knowledge; te whānuitanga – expanding knowledge outward; and te māramatanga – an enlightening of knowledge. It is this enlightening of knowledge that will generate hope for the future.

At this juncture, we find ourselves at a point of discovery that cannot be adequately explained in the English language. This equilibrium point, for want of a better term, is the door to comprehending genuine cultural entanglement and reaching a plane of deeper understanding that exists beyond the superficial. It is the promise of the Treaty – the place that can facilitate the shift from decolonisation to “an ethic of restoration”’ (Jackson, 2020). Here, it is possible to centre our focus on the beauty and opportunity of complexity, instead of on the dichotomy. Getting to this point, via the relational space, can help us look below the surface and beyond reductive dichotomisation of ‘Pākehā’ and ‘Māori’, to focus instead on the nuances and layers of meaning that exist within and across these terms. Durie (2004) describes this as the “exploration of the interface”, where there are opportunities for creating new knowledge that reflect both paradigms. This offers us a means to removing the ceiling. It is a way to move beyond prevailing Western norms, and individualistic, capitalist approaches, which remain embedded in institutional structures.

He Rangahau Whiria can guide us to a place of connection and relational knowing; this can produce an enlightening of knowledge. Here, it is not just about working toward outcomes, but rather the focus is on feeling the guiding principles, the energy of direction, and on the collective movement toward a common goal. Relational knowing enables us to get to a place where the meaning of words like ‘kaupapa’ becomes something that is felt, as opposed to being shoehorned into the closest English-language word or words. Just as alluvial islands and their unique ecologies are vulnerable – capable of being scoured out, swept away, flooded, vanishing altogether – the effects of their presence remain, albeit at times not visible. Channels change under the surface, flows are altered and rapids are created after the island has disappeared. The same can be said of relationships in research, and the unique connections that enable the fertile mixing and mingling of different knowledge streams. Relationships can last forever, though not in a constant, undisturbed, linear trajectory. They drift, get scoured out, flooded, disappear, but can endure – on account of the connection. He Rangahau Whiria offers a departure point for considerate and flourishing connections on Treaty-centred research journeys.

Concluding comments

We draw your attention to American author Heather McGhee’s (2021) book, The Sum of Us. She identifies two overarching barriers to equity: equity seen as a zero-sum game (that is, ‘if black people gain, white people lose’) and deficit-based thinking (that is, ‘black people only have themselves to blame for their lot in life’). These myths are often perpetuated by those who stand to benefit most from the social order they prop up. This is the same system that had, until very recently, viewed mātauranga Māori as irrelevant within academia and often ineligible for research funding. He Awa Whiria cuts across this by drawing knowledge systems into conversation, weaving them, so that alluvial islands are formed; these become places where the seeds of new knowledge ecologies can take root and thrive. Professor Sir Mason Durie (2004, p 1139) encourages Māori to be active participants in this, writing: “Arising from the creative potential of Indigenous knowledge is the prospect that it can be applied to modern times in parallel with other knowledge systems.”

This is relational knowing, nurtured within the context of whitiwhiti kōrero among knowledge holders, who all have something to teach and something to learn. It leads to both new knowledge and the revitalisation of traditional knowledge, at the cutting edge of innovation and future thinking. It is the knowing and the knowledge that will define us as a nation guided by the Treaty of Waitangi. He Awa Whiria helps ensure that the knowledge of Pākehā is valued in a way that also encourages them to step out of the individuality they have inherited from their ancestors. It also ensures that the gifts, talents and ancestral knowledge of Māori will be valued, and the wounds of intergenerational trauma healed. And it is an invitation to others who have made Aotearoa New Zealand their home to weave in their knowledge streams. When this weaving is activated, the knowledge from those alluvial islands will undoubtedly help us solve some of the world’s most pressing issues.

In writing this chapter, we have almost understated the importance of negotiation and flexibility in this methodology – or any bicultural endeavour. By laying out the authors’ different approaches to selected parts of the research process, we have attempted to expose and emphasise the often creative tensions that can chart a researcher’s course. However, getting the most out of the contrasting theoretical and pragmatic underpinnings requires a strong and consistent level of attention to relationships. We feel strongly that this is the most valuable point we can make, as researchers all too often look for a cut-and-dried methodology. Many researchers may feel uncomfortable with a methodology that is not prescribed, even when working alongside colleagues. Yet, this discomfort, for us, is the most crucial and productive part of this partnered and relational research process.

You can’t karakia-at-the-start-of-the-meeting your way out of legacies of colonisation.

Tamatha Paul, 20 July 2022 (quoted in Tang, 2022)

References

A Better Start National Science Challenge (2015), E Tipu E Rea: Revised research and business plans, March 2015 (Wellington: A Better Start National Science Challenge).

Advisory Group on Conduct Problems (2013), Conduct Problems: Adolescent report 2013 (Wellington: Ministry of Social Development).

Awatere, D. (1982), ‘On Maori sovereignty’, Broadsheet, 100.

Belich, J. (1996), Making Peoples: A history of the New Zealanders (Auckland: Penguin).

Berkes, F. (2009), ‘Indigenous ways of knowing and studying of environmental change’, Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand, 39(4), 151–56.

Berman, J., Edwards, T., Gavala, J., Robson, C. & Ansell, J. (2015), ‘He mauri, he Māori: Te iho, te moemoea, te timatanga ō mātou haerenga ki Te Ao Tūroa / Our vision and beginnings of a journey into Te Ao Tūroa (the world in front of us) in Educational Psychology’, Psychology Aotearoa, 7(2), 100–05.

Borrell, B., Moewaka Barnes, H. & McCreanor, T. (2018), ‘Conceptualising historical privilege: The flip side of historical trauma, a brief examination’, AlterNative: An International Journal of Indigenous Peoples, 14(1), 250–34.

Brant Castellano, M. (2004), ‘Ethics of Aboriginal research’, Journal of Aboriginal Health, January, 98–114.

Buick, T.L. (2020), The Treaty of Waitangi (Germany: Outlook Verlag GmbH).

Coombes, B. (2007), ‘Postcolonial conservation and kiekie harvests at Morere New Zealand: Abstracting Indigenous knowledge from Indigenous polities’, Geographical Research, 45(2), 186–93.

Cram, F. & Mertens, D. (2015), ‘Transformative and Indigenous frameworks for mixed and multi method research’, in S.N. Hesse-Biber & R.B. Johnson (eds), The Oxford Handbook of Mixed and Multiple Methods Research (99–109), (New York: Oxford University Press).

Cram, F. & Phillips, H. (2012 December), ‘Reclaiming a culturally safe place for Māori researchers within multi-cultural, transdisciplinary research groups’, International Journal of Critical Indigenous Studies, 5(2), 36–49.

Cram, F., Henare, M., Hunt, T., Mauger, J., Pahiri, D., Pitama, S. & Tuuta, C. (2002), Maori and Science: Three case studies (Auckland: IRI).

Cram, F., Vette, M., Wilson, M., Vaithianathan, R., Maloney, T. & Baird, S. (2018), ‘He awa whiria – braided rivers: Understanding the outcomes from Family Start for Māori’, Evaluation Matters – He Take Tō Te Aromatawai, 4, 165–206.

Dewes, K. (1968), ‘Educational needs and problems of the Māori community’, Address at the 40th ANZACS Congress. Reproduced in Salient, 35(22), 14 September 1972.

Durie, M. (2004), ‘Understanding health and illness: Research at the interface between science and indigenous knowledge’, International Journal of Epidemiology, 33, 1138–43: https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyh250

Fabish, R. (2014), ‘Black Rainbow: Stories of Māori and Pākehā working across difference’, (PhD thesis, Victoria University of Wellington Te Herenga Waka): https://researcharchive.vuw.ac.nz/xmlui/handle/10063/4166

Family Violence Death Review Committee (2020), Sixth report | Te Pūrongo tuaono: Men who use violence | Ngā tāne ka whakamahi i te whakarekereke (Wellington: Health Quality & Safety Commmission).

Hotere-Barnes, A. (2015), ‘Generating “non-stupid optimism”: Addressing Pākehā paralysis in Māori educational research’, New Zealand Journal of Education Studies, 50, 39–53.

Jackson, M. (1993), ‘Land loss and the Treaty of Waitangi’, in W. Ihimaera, H. Williams, I. Ramsden & D.S. Long (eds), Te Ao Marama: Regaining Aotearoa. Māori writers speak out. Volume 2. He Whakaatanga o te Ao – The reality (70–78), (Auckland: Reed).

Jackson, M. (1996), Māori Health Research and Te Tiriti o Waitangi. Hui Whakapiripiri: A hui to discuss strategic directions for Māori health research (Wellington: Te Rōpū Rangahau Hauora a Eru Pomare).

Jackson, M. (2020), ‘Where to next? Decolonisation and stories of the land’, in R. Kiddle, B. Elkington, M. Jackson, O.R. Mercier, M. Ross, J. Smeaton & A. Thomas (eds), Imagining Decolonisation (55–65), (Wellington: Bridget Williams Books).

Jones, A. (2021), ‘When Pākehā acquire te reo’, E-tangata: https://e-tangata.co.nz/reo/alison-jones-when-pakeha-acquire-te-reo/

King, M. (2003), The Penguin History of New Zealand (Auckland: Penguin).

Little Bear, L. (2000), ‘Jagged worldviews colliding’, in M. Battiste (ed.), Reclaiming Indigenous Voice and Vision (77), (Vancouver: UBC Press).

McCreanor, T. (1989), ‘The Treaty of Waitangi: Responses and responsibilities’, in H. Yensen, K. Hague & T. McCreanor (eds), Honoring the Treaty (34–45), (Auckland: Penguin).

McCreanor, T. (2009), ‘Challenging and countering anti-Maori discourse: Practices for decolonisation’, Psychology Aotearoa, 1, 16–20.

McGhee, H. (2021), The Sum of Us: What racism costs everyone and how we can prosper together (Profile Books).

Mead, A.T. (1999), ‘Speaking to Question 6. How are the values of Maori going to be considered and integrated in the use of plant biotechnology in New Zealand?’ Talking Technologies Conference on Plant Technology, 8 May 1999.

Mead, H.M. (2003), Tikanga Māori. Living by Māori values (Wellington: Huia Publishers).

Moewaka Barnes, H. (2000), ‘Kaupapa Maori: Explaining the ordinary’, Pacific Health Dialog, 7(1), 13–16.

Orange, C. (1987), The Treaty of Waitangi (Wellington: Allen & Unwin).

Paki, V. & Peters, S. (2015), ‘Exploring whakapapa (genealogy) as a cultural concept to mapping transition journeys, understanding what is happening and discovering new insights’, Waikato Journal of Education – Te Hautaka Mātauranga o Waikato, 20(2), 49–60.

Pihama, L. (1993), ‘Tungia te ururua, kia tupu whakaritorito te tepu o te harakeke’ (MA thesis, University of Auckland).

Potts, K. & Brown, L. (2005), ‘Becoming an anti-oppressive researcher’, in L. Brown & S. Strega (eds), Research as Resistance: Critical, Indigenous and anti-oppressive approaches (255–86), (Canadian Scholars’ Press).

Ramstad, K.M. & Faulkner, L. (2008), ‘Tikanga & technology: A new net goes fishing’, in J.S. Te Rito & S.M. Healy (eds), Te Tatau Pounamu – The Greenstone Door: Traditional knowledge and gateways to balanced relationships, 2008 Conference Proceedings (248–54), (Ngā Pae o te Māramatanga).

Reid, P. & Cram, F. (2004), ‘Connecting health, people and country in Aotearoa/New Zealand’, in K. Dew & P. Davis (eds), Health and Society in Aotearoa New Zealand (2nd edn., 33–48), (Auckland: Oxford University Press).

Smith, G.H. (2012), ‘Kaupapa Māori: The dangers of domestication’, New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies, 47(2), 10–20.

Smith, L.T. (1992), ‘Te Rapunga i te Ao Marama: The search for the World of Light’, in The Issue of Research and Māori, Monograph No. 9, Research Unit for Māori Education, University of Auckland.

Smith, L., Hemi, M., Hudson, M., Roberts, M., Tiakiwai, S.-J. & Baker, M. (2013), Dialogue at the cultural interface: A report for Te hau mihi ata: Mātauranga Māori, science and biotechnology (Hamilton: University of Waikato).

Tang, E. (2022), ‘Threats against Māori women not taken seriously, says city councillor’, Stuff, 20 July 2022:

www.stuff.co.nz/pou-tiaki/129303363/threats-against-mori-women-not-taken-seriously-says-city-councillor

Te Awekotuku, N. (1991), He Tikanga Whakaaro: Research ethics in the Māori community (Wellington: Manatu Māori).

Te Hennepe, S. (1993), ‘Issues of respect: Reflections of first nation students’ experiences in postsecondary anthropology classrooms’, Canadian Journal of Native Education, 20, 193–260.

Tolich, M. (2002), ‘Pākehā “Paralysis”: Cultural safety for those researching the general population of Aotearoa’, Social Policy Journal of New Zealand, 19, 164–78.

Waipara-Panapa, A. (1995), ‘Body and soul: A socio-cultural analysis of body image in Aotearoa’ (Master’s thesis, University of Auckland).

Waitangi Tribunal (1995), Report of the Waitangi Tribunal on the Motunui-Waitara Claim, WAI6 (Wellington: Waitangi Tribunal).

Walker, S. (2015), ‘New wine from old wineskins: A fresh look at Freire’, Aotearoa New Zealand Social Work, 27(4), 47–56.

Williams, J. (2022), ‘IPANZ Conference speech: Justice Joe Williams on Crown/Māori relations and a 200-year search for partnership’, Australia New Zealand School of Government: https://anzsog.edu.au/news/ipanz-conference-speech-justice-joe-williams-on-crown-maori-relations-and-a-200-year-search-for-partnership/

World Health Organization (1996), Toward a Comprehensive Approach to Health Guidelines for Research with Indigenous Peoples, Report of the Working Group on Research, November 29–December 1, 1995 (Washington, DC: Division of Health Systems and Services Development, Pan American Health Organization, World Health Organization).