11 Whakawhanaungatanga and bicultural research:

Reflections on applying the He Awa Whiria approach to a doctoral research project

Dr. Clare Wilkinson and Professor Angus Macfarlane

Introduction

Whakawhanaungatanga is the process of building, nurturing and maintaining relationships. In my experience, whakawhanaungatanga can be a journey of constructing healthy, meaningful and collaborative relationships to form a bond of trust and respect between people. That bond in turn fosters opportunities for collaboration and innovation.

In August of 2017, I, Clare, lay on the living room floor of my mum’s house in Vermont in the United States. I was doing the final organisation of my travel documents: my student visa, my plane ticket, the contact information for my new flatmates in Ōtautahi Christchurch, Aotearoa New Zealand. In a short time I was due to move across the world to start my doctoral studies at the University of Canterbury (UC). I had just finished my undergraduate degree in geology and was planning to further those studies abroad. I had been offered the opportunity to conduct research into how the rivers around Kaikōura were responding to the landslides triggered by the 2016 Kaikōura earthquake. What follows is my first-person perspective on my research journey, in collaboration with the co-author of this chapter, Professor Angus Macfarlane.

I arrived at UC and started reading about how rivers respond to large earthquakes. I worked closely with my supervisors to develop my research questions. I wanted to include an element of community engagement, which was something I had never done before, but I didn’t know what it should look like. My initial PhD supervisors and I considered several different community groups I could work with, such as infrastructure companies, farmers and the local hapū, Ngāti Kuri. We were aware of, and sympathetic to, research fatigue among these communities and knew that numerous stakeholders were already working with these groups to understand how the earthquake had affected their lives. As such, there was a degree of uncertainty around how this part of the project might unfold. Therefore, while we were starting to build these relationships, we began to explore the effect of the earthquake on local rivers, collect sediment samples, and plan other parts of the project that would help us to learn about sediment transport through earthquake-affected river systems.

During our analysis of literature pertaining to landscape responses to large-scale disturbances, we came across the phrase ‘landscape healing’. It appeared again and again, and piqued our interest, which led to questions like: What does ‘healing’ mean in this context? Who gets to define healing? How can we think about a landscape healing if we don’t include all elements of the landscape, including people? In considering these questions, we knew that the research wouldn’t be as impactful as it could be if it didn’t include a human perspective of landscape change. We figured, who better to talk to about changing and healing landscapes than mana whenua (Indigenous stewards of a tribal area)? I was fortunate to have a conversation with Professor Macfarlane about my research. Professor Macfarlane introduced me to He Awa Whiria and joined my supervisory team. He helped me envisage what an interdisciplinary, bicultural approach to investigating the research questions could look like.

The research

In the context of this study, the He Awa Whiria approach to research highlighted the significance of the connections between people and the landscape; mātauranga Māori was brought to the fore, encapsulating the richness of the knowledge and experience that has been handed down over many generations. The research gave me a newfound appreciation for how mātauranga Māori might be applied in contemporary contexts, in order to make an authentic impact on people and landscapes.

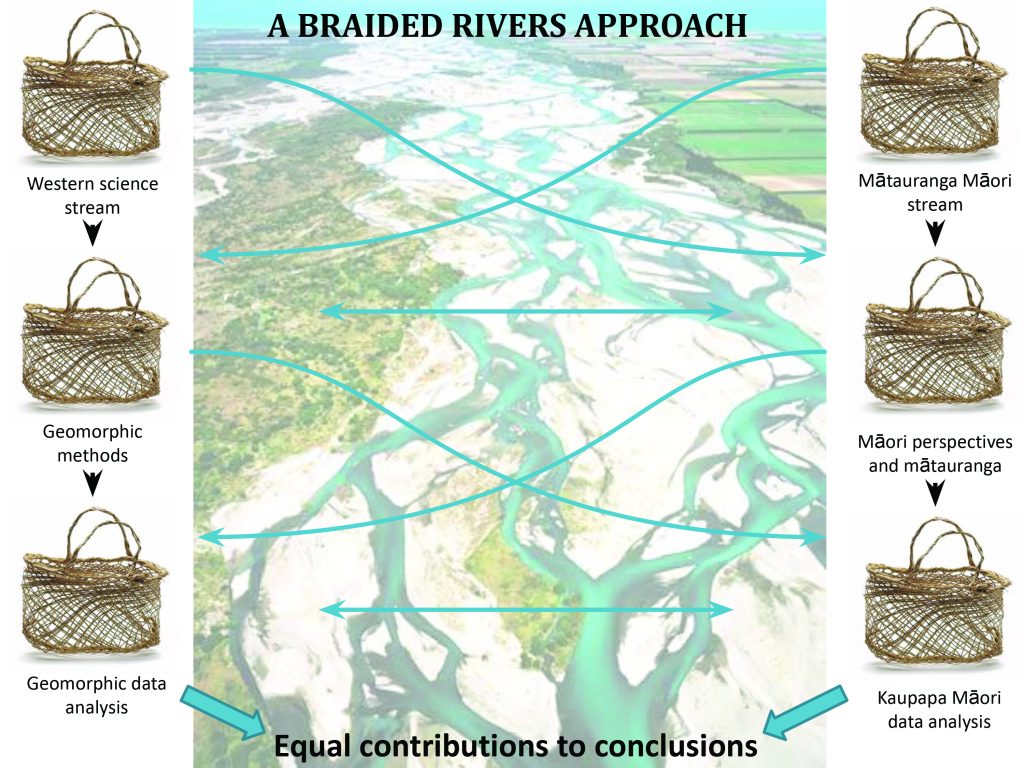

Finding a way to weave mātauranga Māori and river science together was challenging. He Awa Whiria is an approach to research that enables flexibility, but demands diligence. Unlike other frameworks for bicultural research that set out explicit questions to answer or issues to explore, the He Awa Whiria approach relies on the commitment of the researchers to find opportunities to braid the streams of knowledge and various research approaches together (Wilkinson, 2021). My Māori cultural supervisors and mentors guided the process of adapting and applying the He Awa Whiria framework in this study. They helped me identify how and when mātauranga Māori could inform the river-science aspects of the study (see Figure 11.1). By engaging in whakawhanaungatanga with them – and learning from their collective experience and wisdom – it became apparent to me when and where the two streams of knowledge in the research could coalesce.

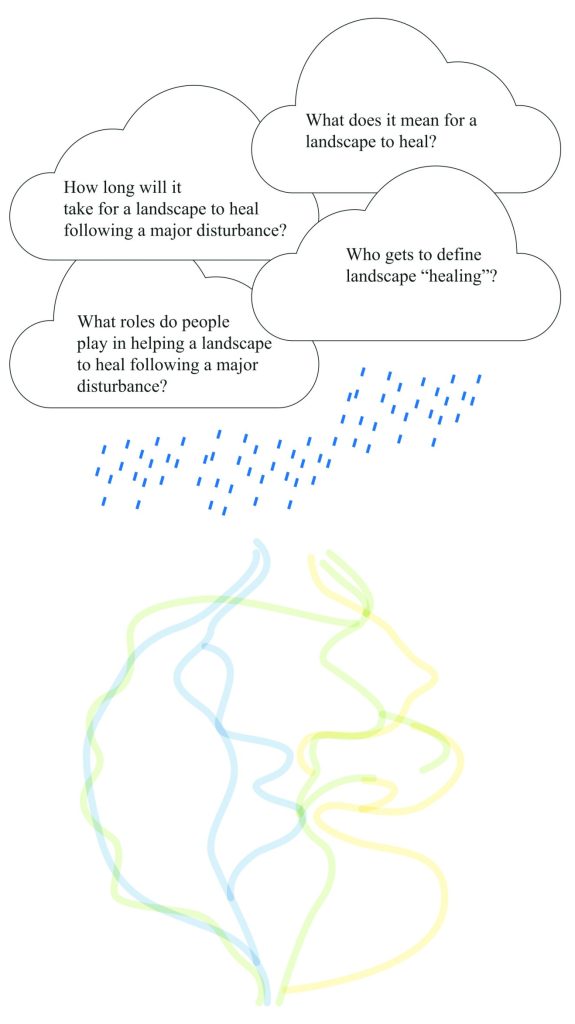

In applying the He Awa Whiria approach in this study, we addressed the research questions in stages, and used metaphors to visualise how the different knowledge streams could merge and diverge. First, we identified the overarching questions that inspired both the research and the approach to conducting the research. As we reflected back to the moments when we first encountered the phrase ‘landscape healing’, the following questions emerged:

• What does it mean for a landscape to heal?

• Who gets to define landscape ‘healing’?

• How long will it take for a landscape to heal following a major disturbance?

• What roles do people play in helping a landscape to heal following a major disturbance?

Figure 11.1: The He Awa Whiria approach, as applied in the doctoral research

From AGCP, 2011 (p 64). Licensed for adaption and re-use under (CC-BY) 4.0.

Ultimately, these questions defined the broad-scale topic of the research, which was captured in the title of my doctoral thesis, ‘Landscape responses to major disturbances: A braided mātauranga Māori and geomorphological study’ (Wilkinson, 2021). They also informed sub-questions the study posed. Essentially, then, the overarching questions were akin to the sources of the knowledge streams; they were the sources that fed the streams of research, as depicted below in Figure 11.2.

Figure 11.2: Overarching research questions

Adapted from Wilkinson, 2021

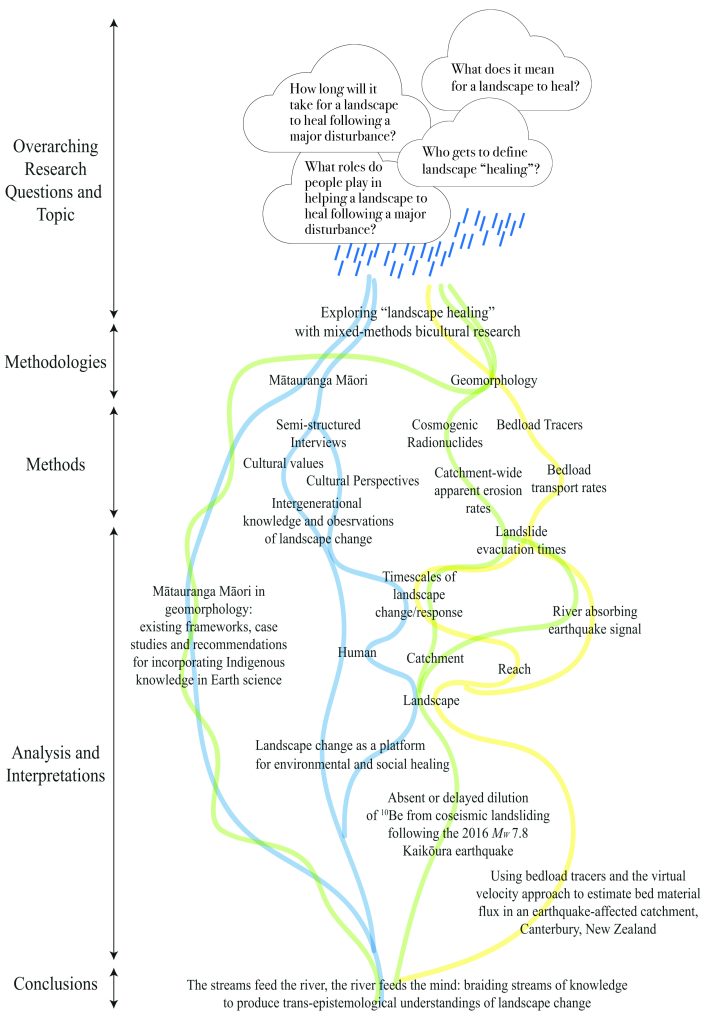

The overarching research questions were represented by the sources of knowledge that guided the study, where these streams include geomorphology and mātauranga Māori. More specifically, the Western stream (geomorphology) represented understanding how rivers respond to large earthquakes, and the mātauranga Māori stream sought to understand how landscapes – physical, cultural and even social – are connected and how they might respond to large disturbances. Therefore, in adopting the He Awa Whiria approach of weaving geomorphology and mātauranga Māori, we used the following methods to address the research questions:

1. geochemical analysis of fine-landslide sediment movement through a river system;

2. tracking the transport of coarse sediment through an earthquake-affected catchment; and

3. literature review and semi-structured interviews with members of different hapū who had deep connections to their local landscapes.

We aligned each of the overarching and sub-questions with one of the three methods used to gather data, as illustrated in Table 11.1 below.

The He Awa Whiria approach guided the analysis of the data; this helped us identify when and where the different streams of research came together, and when they operated independently of each other (see Figure 11.3).

Table 11.1: Research questions and associated methods applied in the thesis

| Research question | Method |

|---|---|

| How are natural disturbances (i.e. earthquakes, floods etc.) perceived to change a landscape? | Mātauranga Māori perspectives (literature review and semi-structured interviews) |

| Should people be/are people involved in helping the landscape to recover? | |

| How long does it take a landscape to recover? Will a landscape ever fully recover? | |

| What are the catchment-averaged erosion rates in the recently disturbed Kaikōura mountains? | Geomorphic methods (geochemical analysis of fine-landslide material and tracking of coarse sediment) |

| What is the effect of a single storm event on the overall transport of fine-stream sediment? | |

| How does landslide-channel connectivity influence the geochemical signature of fine landslide material? | |

| At what rate is the detectable change in geochemical signal propagating downstream in the Tūtae Putaputa (the Conway River)? | |

| How does coarse sediment move through a reach during specific storm events? | |

| What are the estimated export times of coarse landslide-derived sediment? |

Adapted from Wilkinson, 2021

Figure 11.3: Adaptation and application of He Awa Whiria in the study

Adapted from Wilkinson, 2021

The overarching research questions feed the individual research streams’ methodologies and methods, which diverge and converge throughout the research, ultimately coming together to inform the conclusions.

Two further factors contributed to the structure of the thesis. First, this was a thesis made up of several publications, where the individual chapters of the thesis were written as standalone papers to aid in the transferability to (or from, in some cases) peer-reviewed academic journal articles.

Second, another option was that the thesis could be written with mātauranga Māori and science woven together throughout all chapters of the thesis document. During this process of applying He Awa Whiria, two key considerations emerged: as a non-Indigenous researcher, I needed to understand how to responsibly and appropriately approach bicultural research; it was also important that I accurately represent and communicate the work that was being undertaken. In adopting the He Awa Whiria approach and learning about conducting research at the interface[1] (Durie, 2004), I learned that the differing perspectives of mātauranga Māori and Western science cannot be viewed through the same lens. Rather, they need to be viewed separately, in order to maintain their respective epistemological integrities (Rauika Māngai, 2020). As such, and in accordance with the He Awa Whiria approach, we structured the research in a way that enabled both epistemologies to occupy their own independent streams, when most appropriate, but that also enabled them to come together at times, to inform, guide and strengthen one another.

Alongside learning about how to conduct research at the interface, I was also learning a lot about myself. I realised that my motivations for the research were driven by some of my personal experiences. One of the most powerful learnings I gained from my doctoral experience occurred when one of my supervisors encouraged me to open my thesis with a personal reflection. That reflection illuminated the genesis of this research – the layers upon layers of experiences and relationships with people and places that had inspired me to ask the questions I was asking. This journey of self-reflection made me realise how important it is to understand why we ask the questions we ask and why we are passionate about our passions. Feedback on including a personal reflection in the thesis was mixed; it was deemed to be unconventional, and unconventionality could lead to vulnerability, which is risky. However, risk can reap rewards, and the process ended up being a very rewarding one for me.

As I applied the He Awa Whiria approach in writing my thesis, the metaphor of He Awa Whiria – a braided river – came to life. It illustrated for me how the knowledge streams could exist independently but also in alliance with one another. Following the personal reflection and the general introduction to the thesis, the document contained five main chapters. The first chapter was a literature review that acknowledged how geomorphology and mātauranga Māori can work together in research. I identified case studies and reviewed research frameworks and approaches – including He Awa Whiria. These frameworks and approaches each resonated with the idea of weaving together mātauranga Māori and geomorphology. The next three chapters each reflected one of the three streams of the research, including the research methods (see Figure 11.3). The final chapter took the lessons and learnings from the previous chapters and wove them together in the spirit of He Awa Whiria; here, both the mātauranga Māori and Western-science streams provided equitable contributions to the overall findings, and to the subsequent conclusions that were drawn in the study.

The research generated outcomes that may not have been unearthed had it not been for the presence of He Awa Whiria in the study; exposure to an alternative way of viewing landscapes and landscape change was illuminating. In essence, the stories that emerged from the research were gifted to – rather than written by – me. Through the fluvial-geomorphology streams, the landscape shared stories about how the rivers were responding to the earthquake. Through the interviews, stories from individuals emerged – about their relationships with the land and their experiences of observing landscape change following major disturbances. Therefore, the outcomes of this research were both a bicultural narrative of a particular river’s earthquake story and a biculturally informed concept for understanding landscape change. These outcomes are described below.

A case study in the thesis presented the story of Tūtae Putaputa (Conway River) – one of the rivers affected by the 2016 Kaikōura earthquake. The case study relied on not only the results of the different streams of research applied in the project, but also the process of conducting those streams of research. It drew upon these learnings, as well as goals set by mana whenua for Tūtae Putaputa in environmental management plans and in the Ngāi Tahu Treaty claims settlement. This story is told in the following extract[2] (Wilkinson, 2021):

Around midnight on 14 November 2016, Rūaomoko (the atua – Māori god – of earthquakes and volcanoes) rolled over. In the form of seismic waves, he transmitted his energy from deep within Papatūānuku’s (Earth Mother’s) embrace to the surface – Te Ohomauri o te Whenua, the Awakening Lifeforce of the Land. Rūaomoko’s unrest registered as an Mw 7.8 earthquake on seismographs around the world – he iti te mokoroa nāna te kahikatea i kakati, even the small can make a large impact on the big. Papatūānuku accommodated Rūaomoko’s activities by dissipating his released energy over an area of nearly 10,000 km2, in the form of horo whenua (landslides), surface ruptures, and coastal uplift. Papatūānuku’s voice resounded across the region, heard by the many hundreds of people awoken in the night by the sound of her moving around them – puraho maku, kei ngaure o mahi, let others acknowledge [her] strength. After about two minutes, Papatūānuku relaxed, but dust from landslides and surface ruptures, splashes of the sea onto the shore, and the roar of rivers remained – tihei mauri ora (the breath of life), Papatūānuku exhaled.

Tūtae Putaputa, nestled in the Seaward Kaikōura Mountains, experienced Papatūānuku’s exhalation as sediment shed from hillslopes via approximately 2,600 horo whenua. Some of the horo whenua travelled to the valley floor, blocking water from upstream. Cobbles within Tūtae Putaputa’s waters at the rangefront indicate that Tūtae Putaputa is only transporting about 0.003–0.015 Mt of bedload per year, which is on par with the amount of bedload that Tūtae Putaputa has conveyed in the past in the absence of an earthquake. Additionally, some of Tūtae Putaputa’s smallest sediments, sands 250–500 μm in size, indicate that Tūtae Putaputa as a whole is not showing a catchment-wide signal of the earthquake. Spending time with Tūtae Putaputa reveals that most of the horo whenua in the catchment are still perched on its hills or stored in its terraces. Scientists have determined that the total amount of material released from Tūtae Putaputa’s hillslopes is about 12.3 M m3, and that only about 13% of the landslides made contact with Tūtae Putaputa’s waters. The information provided by Tūtae Putaputa communicates that it is possible that Tūtae Putaputa will hold on to the landslide material for hundreds or maybe thousands of years to come. Tūtae Putaputa appears to be capable of absorbing the impacts of the earthquake well. Just over four years after the earthquake, all of Tūtae Putaputa’s landslide dams have made space to re-welcome Tūtae Putaputa’s waters to flow. Some water is still held in the lakes behind the dams, but the lakes are much smaller today than they were four years ago. Some ground cracking still exists, but these cracks are believed to be capable of healing in time. Tūtae Putaputa and its catchment will heal its own scars by revegetating landslides, letting wind blow new sediment into the cracks, and by finding ways to accommodate the sediment that moved from the hillslopes to the riverbed.

Despite Tūtae Putaputa’s apparent ability to absorb the impacts of such an event, Tūtae Putaputa faces other ongoing challenges. In the past few decades, Tūtae Putaputa has become host to beef and sheep farms, willows, and other species introduced by European colonisation. These changes have caused Tūtae Putaputa’s mauri (life force) to decrease; Tūtae Putaputa no longer has clean drinking water to share with people, nor much native vegetation in which to shelter native birds. Ngāti Kuri, the tangata (people) who know Tūtae Putaputa’s past, see this degradation. Yet, despite what has departed from Tūtae Putaputa’s care – such as the birds, the native vegetation, and the mauri o te wai (life force of the water) – Tūtae Putaputa still gives. Tūtae Putaputa provides sediment and water for people; gravel and water extraction activities occur in multiple places within Tūtae Putaputa’s boundary. Tūtae Putaputa may have been able to absorb the earthquake so well because it is conditioned to adapt to major changes; it has already shown its ability to endure through alterations, large and small.

Tūtae Putaputa tells us that even the events that seem most dramatic, most damaging, most scarring, can be managed relationally. In the past, Tūtae Putaputa provided mahinga kai (cultural opportunities) for its people. The relationships between land, water, and people were sustainable and reciprocal. The people had responsibilities to Tūtae Putaputa as well, to keep it clean and to ensure their activities enabled the sustenance of Tūtae Putaputa’s mauri. Today, Tūtae Putaputa’s advocates, Ngāti Kuri, fight for Tūtae Putaputa’s right to continue giving and receiving, for Tūtae Putaputa’s right to be a river ki uta ki tai (from the mountains to the sea), and for their own ability to uphold Tūtae Putaputa’s rights. The people acknowledge that Tūtae Putaputa will endure far longer than the people, so the people must act in ways that respect the longevity of Tūtae Putaputa – whatungarongaro he tangata toitū te whenua, people are fleeting but the land remains. Indeed, nature has a way of healing iteslf – i timu noa te tai, certain conditions are best left to work themselves out – and it is the people who must learn to adapt. By absorbing the impacts of the earthquake so well, perhaps Tūtae Putaputa aims to tell us it is still strong, but there are other issues of more importance than the earthquake. Indeed, perhaps the entire earthquake event was Papatūānuku trying to tell us something.

The 2016 Kaikōura earthquake highlights that it is not just the land that will heal, but the people as well. The earthquake provided an opportunity for change, for people to realise their responsibilities to the land and to each other. Adaptability to such an event can take place by recognising connections, acting sustainably, and attending to reciprocity. Tūtae Putaputa exemplifies this message; having experienced many large earthquakes in the past, Tūtae Putaputa demonstrates adaptability by sustaining its connections to humans and non-humans through giving resources and shelter and by allowing time to write its story. Healing connections to land may help people hear this story, and understand the role that the Kaikōura earthquake has – and will have – in the larger history of this landscape. Tūtae Putaputa shows us that we can come to realise more if we consider all ways of understanding its story – ka mate kāinga tahi, ka ora kāinga rua, there is more than one way to achieve an objective.

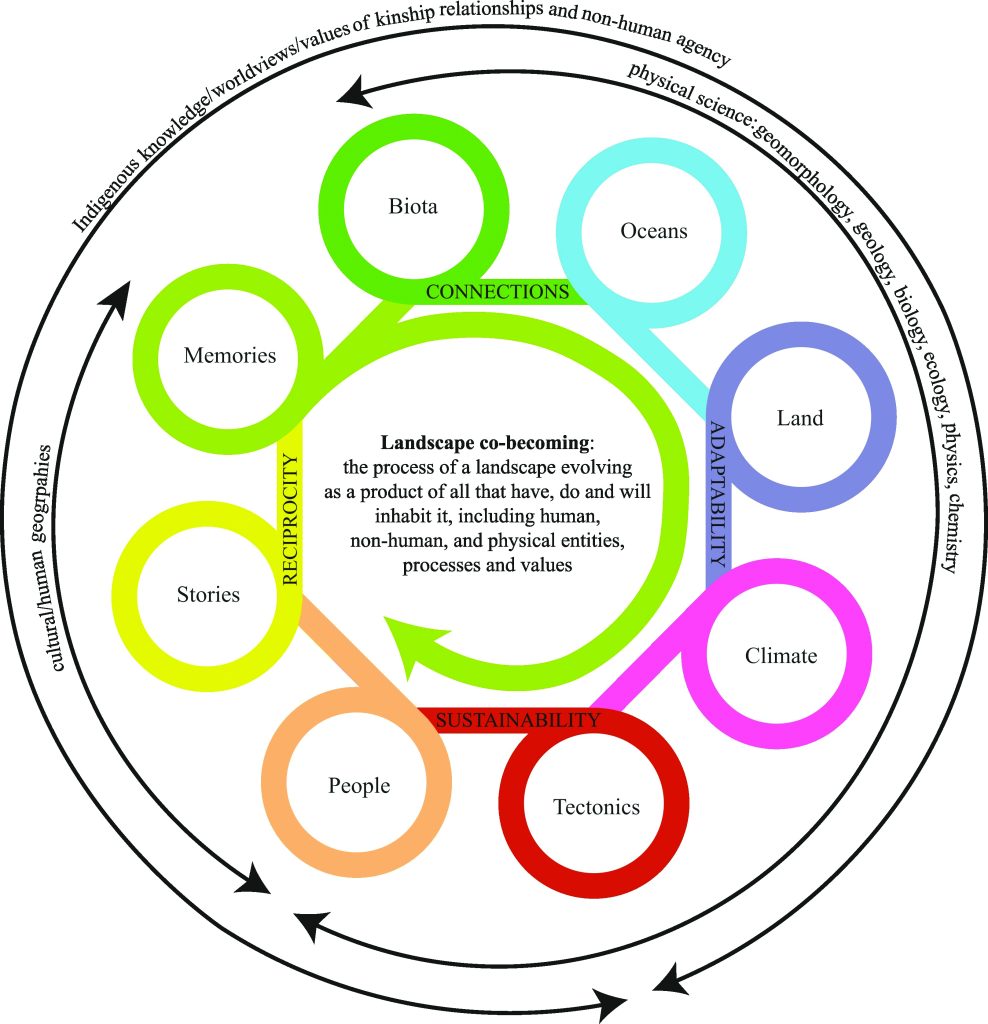

The above bicultural narrative of Tūtae Putaputa’s earthquake story – further woven with other learnings from critical geography, linguistics, Indigenous philosophy, ecology, biology and even psychology – inspired a process framework for thinking about landscape evolution that incorporates cultural and human geographies, Indigenous knowledge and worldviews, and physical science. The concept, termed ‘landscape cobecoming’, is inspired by the recognition that people and landscapes – and all the physical and metaphysical aspects of landscapes – become, or experience the process of becoming, together (such as Country et al., 2016). The concept builds upon uni-directional, landscape-evolution theory and bi-directional, relational-feedback frameworks to arrive at a multi-directional, multi-dimensional, process framework. This framework prioritises Indigenous knowledge by acknowledging that mountains, oceans, rivers, lakes, flora, fauna, people and stories are connected, and by recognising that all of the natural world is related (see Figure 11.4). Landscape co-becoming promotes Indigenous methodologies by recognising that the stories of landscapes are not complete without the perspectives and knowledge of mana whenua – the traditional peoples with ancestral connections to the land. Figure 11.4 below illustrates this concept, wherein the curved arrows indicate the topics pertinent to, or typically explored in, the different ways of studying the Earth’s surface. These are identified by the text corresponding with each arrow.

Figure 11.4: Landscape co-becoming as a conceptual process framework

From Wilkinson, 2021, p 169

Following the He Awa Whiria approach for this research resulted in two research outcomes (the bicultural narrative and the process framework) that neither mātauranga Māori nor fluvial geomorphology would have produced in isolation. That is the essence of He Awa Whiria: the generation of knowledge that could not have come from any single epistemology alone. Through applying the He Awa Whiria approach, we were able to forge connections and establish relationships through the experience of whakawhanaungatanga. The He Awa Whiria approach also illuminated the connections and relationships between the various aspects of the study – specifically people, place and language.

The following paragraph is a paraphrased excerpt from my personal reflection in the thesis, where I highlighted and reflected upon my learnings – learnings that were made possible only by having followed the He Awa Whiria approach:

In te reo Māori (the Māori language), whenua, or land, is the same word used for placenta. The dual meaning illustrates the inseparable bond between mother, child and land, linked through whakapapa, or ancestry. In Hawaiian culture, ‘āina loosely translates to land, but more deeply means “that which feeds” (Case, 2019). Connection to land is a connection to the sustainer. In the Anishinaabe language, the language of the Anishinaabe people of the United States, aki also translates to land, but more truly means the living land, the inspirited, animate land, and the Earth that sustains (Kimmerer, 2013). Many Indigenous scholars and individuals have indicated that reconnecting with land has the ability to fill the wairua, fill the spirit. In fact, scientists have recently shown that the smell of soil, of Mother Earth, generates a release of oxytocin in the human endocrine system, the same hormone that is released when a human mother and child embrace (Kimmerer, 2013). This provides one explanation of the bond between people and land through concepts of whenua, ‘āina, aki, and for me, the smell of fresh soil as I walk up a riverbed with landslides on the surrounding hillslopes. Up a stream where loose soil and debris sits on the hillslope, the smell of Earth fills the valley. My science, my research, and my learnings from Te Ao Māori (the Māori world) have taught me lessons about physics and chemistry and Earth systems, but also about connections, reciprocity and love. And so, for me, studying geomorphology, studying landslides and rivers, surrounds me with the smell of fresh soil, of Mother Earth, of Papatūānuku’s exhale, providing a personal understanding of why science, culture and Indigenous knowledge can provide more information together than they could alone.

Conclusions and recommendations

In closing, I share an excerpt from the final chapter of my thesis, in the three paragraphs below. These reflections indicate my recommendations to students wishing to follow the He Awa Whiria approach in their research. They also capture a reflection on applying He Awa Whiria as a research approach or process.

He Awa Whiria requires Māori mentorship and guidance; it is not an approach that non-Māori or non-Indigenous researchers could use without input, guidance, and support of Māori colleagues or communities. At the moment, braiding the streams of two knowledge epistemologies can only justly be done by someone who has been raised with one foot in each world, or by someone who is fortunate enough to learn from someone who has that cross-epistemological experience. My application of He Awa Whiria for this work addresses my research questions and aims, but would not have been possible without the support of my Māori supervisors, mentors and participants – those who gifted me their time, knowledge and perspectives.

Applying He Awa Whiria requires the researcher to embrace the ways of knowing, thinking, and relating to the research that are imbedded in the different epistemologies. Some other research frameworks or concepts that use water as an analogy (e.g. Maxwell et al., 2020; Leduc, 2020) involve researchers being in a boat, travelling downstream or paddling together. Though these frameworks may be useful for conceptualising the partnered journey through research, He Awa Whiria requires that the researcher takes an additional step to occupy both streams simultaneously in order to effectively braid the streams. Occupying both streams at the same time, and figuratively becoming the river, matches well with the metaphors imbedded in the He Awa Whiria framework. To occupy all streams at once, the researcher must be the river, be the awa: Ko au te awa, ko te awa ko au.[3]

One of the main goals of He Awa Whiria is to generate new knowledge, understandings and solutions that neither body of knowledge (i.e. science and mātauranga Māori) could produce in isolation (Macfarlane and Macfarlane, 2018). Applying He Awa Whiria addressed the overarching research questions and the specific research questions of the thesis. Moreover, applying He Awa Whiria to this work produced the conceptual process framework of ‘landscape co-becoming’, an idea that would not have been developed if this research had not included the many elements (science, geomorphology, mātauranga Māori, cultural geographies, etc.) that it does. With the guidance and support of my Māori supervisors and participants (and my non-Māori supervisor), successful application of He Awa Whiria resulted in the foundations of a new, innovative concept. Much work will need to occur for this concept to be advanced and used in geomorphology and to appeal to both progressive geomorphologists and more traditional geomorphologists, but it provides the foundation for transformative ways of conceptualising landscape change and evolution. ‘Landscape co-becoming’ embraces the concept of he waka eke noa (a canoe which we are all in with no exception), and acknowledges that everyone and everything on this planet are part of landscape change and we have a responsibility to know, understand, and care for this planet. We can accomplish knowing our planet through science or Indigenous knowledge, but they are better together: nāu te rourou, nāku te rourou, ka ora ai te iwi, with your basket and my basket, the people will thrive.

My final reflection is a consideration of how following the He Awa Whiria approach as a non-Māori researcher might look in practice. Ultimately, it will be different for everyone, and everyone will have a different journey. In order for me to successfully apply He Awa Whiria in this study, it was important to recognise and acknowledge the collective, and to also acknowledge how the team adapted He Awa Whiria for the purposes of this particular research project. As a non-Māori researcher, I was not conducting kaupapa Māori research, which is often incorporated into the Māori knowledge stream of the He Awa Whiria framework. However, this study was guided by Māori collaborators and colleagues, therefore a number of kaupapa Māori research principles were adhered to in order to ensure cultural safety for researchers and participants alike. The He Awa Whiria approach is flexible and adaptable, making it versatile for many different types of research. Its strength comes from the connections it reveals and builds. It is whakawhanaungatanga in research.

References

Aho, L.T. (2019), ‘Te Mana o te Wai: An indigenous perspective on rivers and river management’, River Research and Applications, 35(10), 1615–21: https://doi.org/10.1002/rra.3365

Case, E. (2019), ‘I ka Piko, to the Summit: Resistance from the mountain to the sea’, Journal of Pacific History, 54(2), 166–81: https://doi.org/10.1080/00223344.2019.1577132

Country, B., Wright, S., Suchet-Pearson, S., Lloyd, K., Burarrwanga, L., Ganambarr, R., Ganambarr-Stubbs, M., Ganambarr, B., Maymuru, D. & Sweeney, J. (2016), ‘Co-becoming Bawaka: Towards a relational understanding of place/space’, Progress in Human Geography, 40(4), 455–75: https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132515589437

Dellow, S. & Massey, C. (2017), ‘Kaikoura earthquake – landslide dams: Identifying the hazard and managing the risks’, NZ Geomechanics News: www.nzgs.org/library/kaikoura-earthquake-landslide-dams-identifying-the-hazard-and-managing-the-risks/

Durie, M. (2004), ‘Exploring the interface between science and indigenous knowledge’, in Capturing Value from Science: [PDF] ww.researchgate.net/profile/Mason_Durie/publication/253919807_Exploring_the_Interface_Between_Science_and_Indigenous_Knowledge/links/573d839108aea45ee842959f.pdf

Hatem, A.E., Dolan, J.F., Zinke, R.W., Dissen, R.J.V., McGuire, C.M. & Rhodes, E.J. (2019), ‘A 2000 yr paleoearthquake record along the Conway segment of the Hope Fault: Implications for patterns of earthquake occurrence in northern South Island and southern North Island, New Zealand’, Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, 109(6), 2216–39: https://doi.org/10.1785/0120180313

Kimmerer, R.W. (2013), Braiding Sweetgrass: Indigenous wisdom, scientific knowledge and the teachings of plants (Minneapolis, MA: Milkweed Editions).

Langridge, R., Campbell, J., Hill, N., Pere, V., Pope, J., Pettinga, J., Estrada, B. & Berryman, K. (2003), ‘Paleoseismology and slip rate of the Conway Segment of the Hope Fault at Greenburn Stream, South Island, New Zealand’, Annals of Geophysics, 46(5): 1119–39: www.earth-prints.org/handle/2122/1007

Langridge, R.M., Rowland, J., Villamor, P., Mountjoy, J., Townsend, D.B., Nissen, E., Madugo, C., Ries, W.F., Gasston, C., Canva, A. et al. (2018), ‘Coseismic rupture and preliminary slip estimates for the Papatea Fault and its role in the 2016 Mw 7.8 Kaikōura, New Zealand, earthquake’, Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, 108(3B), 1596–622: https://doi.org/10.1785/0120170336

Leduc, T.B. (2020), ‘Falling with Heron: Kaswén:ta teachings on roughening waters’, Social & Cultural Geography, 21(7), 925–39: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/14649365.2018.1500633

Macfarlane, S. & Macfarlane, A.H. (2018), Toitū Te Mātauranga: Valuing culturally inclusive research in contemporary times, A position paper prepared under the auspices of the Māori Research Laboratory, Te Rū Rangahau, at the University of Canterbury.

Macfarlane, S., Macfarlane, A. & Gillon, G. (2015), ‘Sharing the food baskets of knowledge: Creating space for a blending of streams’, in A. Macfarlane, S. Macfarlane & M. Webber (eds), Sociocultural Realities: Exploring new horizons (52–67), (Christchurch: Canterbury University Press).

Massey, C., Townsend, D., Rathje, E.M., Allstadt, K.E., Lukovic, B., Kaneko, Y., Bradley, B.A., Wartman, J., Jibson, R.W., Petley, D.N. et al. (2018), ‘Landslides triggered by the 14 November 2016 Mw 7.8 Kaikōura Earthquake, New Zealand’, Bulletin of the Seismological Society of America, 108(3B), 1630–48: https://doi.org/10.1785/0120170305

Massey, C.I., Townsend, D., Jones, K., Lukovic, B., Rhoades, D., Morgenstern, R., Rosser, B., Ries, W., Howarth, J., Hamling, I. et al. (2020), ‘Volume characteristics of landslides triggered by the MW 7.8 2016 Kaikōura Earthquake, New Zealand, derived from digital surface difference modelling’, Journal of Geophysical Research: Earth Surface: https://doi.org/10.1029/2019JF005163

Maxwell, K.H., Ratana, K., Davies, K.K., Taiapa, C. & Awatere, S. (2020), ‘Navigating towards marine co-management with Indigenous communities on-board the Waka-Taurua’, Marine Policy, 111, 103722: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.marpol.2019.103722

Ministry of Social Development (2011), Conduct Problems: Effective programmes for 8–12 year olds, 2011 (Wellington: Ministry of Social Development)

Ngāi Tahu Claims Settlement Act 1998, No. 97 (as 01 August 2020), Public Act Schedule 65 Statutory acknowledgement for Tūtae Putaputa (Conway River) –, New Zealand Legislation: www.legislation.govt.nz/act/public/1998/0097/latest/DLM430898.html

Power, W., Clark, K., King, D.N., Borrero, J., Howarth, J., Lane, E.M., Goring, D., Goff, J., Chagué-Goff, C., Williams, J. et al. (2017), ‘Tsunami runup and tide-gauge observations from the 14 November 2016 M7.8 Kaikōura earthquake, New Zealand’, Pure and Applied Geophysics, 174(7), 2457–73: https://doi.org/10.1007/s00024-017-1566-2

Rauika Māngai (2020), A Guide to Vision Mātauranga: Lessons from Māori voices in the New Zealand science sector (Wellington: Rauika Māngai): [PDF] https://bioheritage.nz/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/Rauika-M%C4%81ngai_A-Guide-to-Vision-M%C4%81tauranga_FINAL.pdf

Redfern, F. (2017), Life on Muzzle (Auckland: Random House New Zealand).

Stirling, M., Litchfield, N.J. & Villamor, P. (2017), ‘The Mw 7.8 2016 Kaikoura earthquake: Surface fault rupture and seismic hazard context’, Bulletin of the New Zealand Society for Earthquake Engineering, 50(2), 73–84.

Sunde, C. (2006), ‘Healing ecological and spiritual connections through learning to be non-subjects’, Australian Ejournal of Theology, 8(1), 1–6: https://researchspace.auckland.ac.nz/handle/2292/18731

Te Rūnanga o Kaikōura (2007), Te Poha o Tohu Raumati: Te Rūnanga o Kaikōura Environmental Management Plan (Kaikōura: Te Rūnanga o Kaikōura): [PDF] https://ngaitahu.iwi.nz/wp-content/uploads/2013/08/Te-Runanga-o-Kaikoura-Environmental-Management-Plan.pdf

Wilkinson, C. (2021), ‘Landscape responses to major disturbances: A braided mātauranga Māori and geomorphological study’ (PhD thesis, University of Canterbury).

- Research at the interface (Durie, 2004), in this context, is research at the interface of mātauranga Māori and Western science. This research approach aims to bring together the two sets of methods and associated values in a way that benefits both epistemologies. ↵

- References have been removed to increase readability. The following sources were referenced in the original text: Massey et al., 2018; Langridge et al., 2018; Redfern, 2017; Stirling et al., 2017; Massey et al, 2020; Power et al., 2017; Dellow and Massey, 2017; Te Rūnanga o Kaikōura, 2007; Ngāi Tahu Claims Settlement Act 1998; Hatem et al., 2019; Langridge et al., 2003; Sunde, 2006; and Wilkinson, 2021. The bicultural narrative also draws upon conversations with a member of Ngāti Kuri and Māori whakataukī (proverbs) to illustrate the story. ↵

- Ko au te awa, ko te awa ko au (I am the river, and the river is me) is a whakataukī typically attributed to the people of the Whanganui River on the North Island of Aotearoa New Zealand to describe their ancestral connection to the Whanganui River. This whakataukī is acknowledged in the recognition of the Whanganui River’s legal personhood, and indicates the interconnectedness of people, place and environment (Aho, 2019). ↵