8 The Better Start Literacy Approach:

Using He Ara Whiria to inform design

Professor Gail Gillon; Jennifer Pearl Smith; Rachel Maitland; Associate Professor Sonja Macfarlane; and Professor Angus Macfarlane

Introduction

Reducing education and health inequities is a complex global challenge. Efforts to address this challenge have been hampered by the significant adverse effects on children’s learning from the Covid-19 pandemic and school closures (Goldenberg, 2013; Relyea et al., 2023; Tomaszewski et al., 2022). For some learners this effect has been profound, and our aspiration of meeting the United Nations’ 2030 sustainability goal of inclusive and equitable quality education for all (United Nations, 2015) is currently under threat. The need for large-scale implementation of comprehensive approaches to early literacy instruction, based on the science of reading, is being highlighted as one important strategy to address current inequities (Fien et al., 2021; Gonzalez et al., 2022). Strong foundational literacy skills facilitate children’s education success. Higher standards of academic achievement, in turn, are positively associated with improved health, economic and life outcomes, which lead to intergenerational advantages (Ross and Mirowsky, 2011).

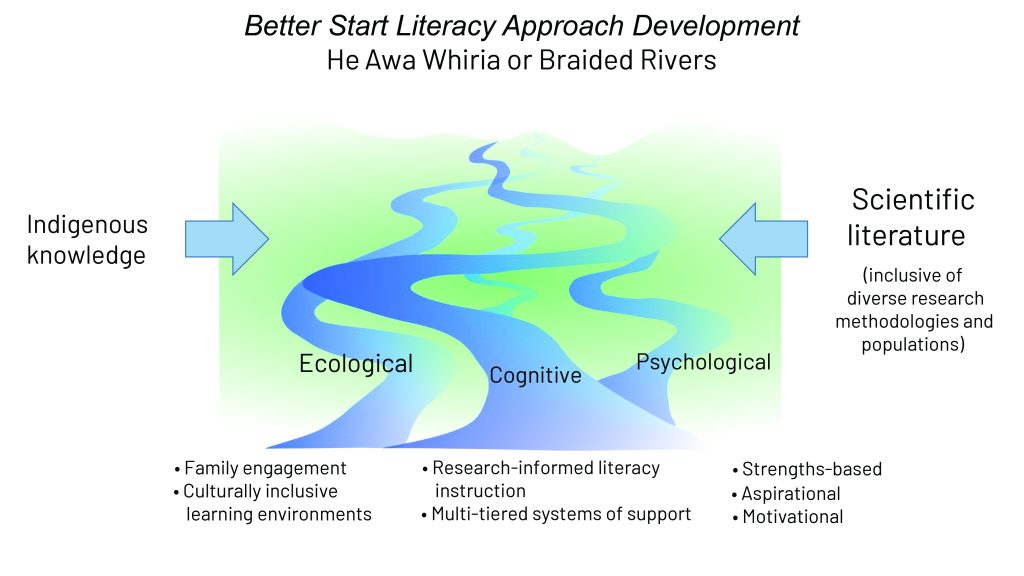

In the design of science-based early literacy approaches, attention is focused on robust research findings. Understanding the critical cognitive skills necessary for written-language acquisition, as well as identifying teaching strategies that are effective and efficient in advancing these core cognitive skills, is essential. However, attention must also be paid to the ecological and psychological influences on children’s reading achievement. As Macfarlane reminded us in his text Kia Hiwa Ra!: Listen to culture (2004), it is important to build upon children’s cultural strengths and experiences in helping them acquire new knowledge. If we are to address the needs of all learners, we must ensure the designs of our early literacy approaches go beyond the teaching of cognitive skills, to inspire and motivate our students to learn to read through culturally relevant and culturally responsive teaching strategies (Bell and Clark, 1998; D’Aietti et al., 2021; Gillispie, 2021). We need to consider the power of early literacy success to build our young learners’ positive cultural identity, cultural knowledge and self-efficacy (Duckworth et al., 2021).

In this chapter we discuss how the He Awa Whiria framework (Macfarlane et al., 2015) informed the development of an early literacy initiative referred to as the Better Start Literacy Approach (Gillon et al., 2023). The Better Start Literacy Approach (BSLA) was specifically designed for the Aotearoa New Zealand English-medium education context and is an example of a multi-tiered system of support (MTSS) approach to facilitate all children’s early literacy success. BSLA is currently being implemented throughout New Zealand junior-school classrooms. The authors of this chapter bring their collective views on how BSLA braids together knowledge related to differing influences on early literacy achievement, particularly for young Māori learners.

He Awa Whiria framework

In New Zealand, the braiding together of differing epistemologies to inform policy and practices – with a particular focus on including Māori and Indigenous knowledge – has gained significant attention. He Awa Whiria depicts this weaving of knowledge through the imagery of a braided river. Braided rivers are a special feature of the New Zealand landscape, particularly across the Canterbury Plains in the South Island, and have both ecological and cultural significance. Macfarlane and colleagues (Gillon and Macfarlane, 2017; Macfarlane et al., 2015) advanced this metaphor of a braided river within an educational learning context. It has also been used by others in health and social sciences to understand the efficacy of differing practices for Māori whānau (for example, Cram et al., 2018). Indigenous knowledge has its own integrity, value and influence. At times, though, the braiding of Indigenous knowledge with other knowledge can positively address the educational and health aspirations of culturally diverse and Indigenous communities. Gillon and Macfarlane (2017) discussed He Awa Whiria in relation to children’s phonological awareness and reading development. They discussed the braiding together of knowledge that facilitates success for Māori and other Indigenous learners with knowledge gained from Western-science experimental studies (for example, studies that predominantly include children from Western cultures who are either English-language native speakers learning literacy within English-language education contexts or are native speakers of the dominant language of literacy instruction). They based the braiding of knowledge on Aaron and colleagues’ earlier work (Aaron et al., 2008), related to the component model of reading. The component model highlighted the ecological, psychological and cognitive influences on children’s reading development. This chapter extends this earlier work, by considering how He Awa Whiria informed multiple levels of support for teachers and literacy specialists to support their successful implementation of BSLA within junior-school classes.

The Better Start Literacy Approach

In 2014 the New Zealand government launched a major ten-year research initiative to advance knowledge towards addressing significant national and global challenges. This initiative was called the National Science Challenges. Following extensive consultation, one of these challenges was focused on children’s wellbeing and was called A Better Start National Science Challenge (Maessen et al., 2023). A Māori name was gifted to the challenge, E Tipu e Rea. It refers to advice given by Sir Apirana Ngata (1874–1950), a Māori tribal leader and politician, to a Māori child: “E tipu e rea mo ngā rā o tō ao. Grow tender shoot for the days destined to you” (Maessen et al., 2023). Ngata’s advice continued with referring to embracing the new ways of the European settlers, but holding close the wisdom and treasures of Māori ancestors.[1] It reflected Ngata’s considerations of biculturalism as a response to the assimilationist views of his era (Sissons, 2000). This advice, in many ways, captures the essence of He Awa Whiria – braiding together different knowledge to thrive and succeed in our modern world.

As part of the Successful Learning theme within A Better Start National Science Challenge, researchers were challenged to consider how to raise early literacy achievement for children within their diverse communities. Through a co-constructed and iterative process involving researchers, Māori and Pacific leaders, teachers, literacy specialists, speech-language therapists and community leaders, the Better Start Literacy Approach (BSLA) emerged. Following successful, controlled pilot trials demonstrating its effectiveness (Gillon et al., 2019; 2020; 2023), the New Zealand government funded teachers and literacy specialists to receive comprehensive professional learning and development to implement the approach. New-entrant and junior-school class teachers throughout the country are now implementing this approach with the support of in-school or local literacy specialists.

BSLA is a strengths-based and culturally responsive approach to early literacy instruction. It braids together robust research evidence from differing knowledge streams, including knowledge of what facilitates success for Māori learners. The next section describes how these differing knowledge streams informed BSLA within the He Awa Whiria framework.

Multi-tiered system of support

BSLA is an example of a MTSS framework to advance children’s early literacy (reading, writing and oral-language skills). It is a proactive approach to ensuring early literacy success for all learners. A key feature of MTSS frameworks (also aligned to Response to Intervention models (Arias-Gundín and Llamazares, 2021)) is the systematic monitoring of children’s early foundational-literacy skills (for example, phonological awareness, alphabet knowledge, word reading and spelling skills). Monitoring-assessment data inform teachers’ understanding of how children are responding to quality literacy instruction. Where data suggest children are not responding as expected to class-level teaching (referred to as Tier 1 support), teaching is adapted to better suit learners’ needs, through more targeted, small-group teaching (Tier 2 support). The next level of support, more personalised and individual teaching (Tier 3 support), is activated as necessary, to ensure every child’s literacy-learning needs are being met.

Investigations of MTSS frameworks for literacy instruction have predominately focused on their effectiveness in developing children’s cognitive skills. However, more recently, the inclusion of culturally responsive practices within MTSS has been advocated. Such inclusion may be particularly important for literacy development in children from culturally and linguistically diverse communities (Gonzalez et al., 2022; Linan-Thompson et al., 2022). BSLA purposefully braids strengths-based and culturally responsive practices together with the monitoring assessment and tiers of support that are characteristic of MTSS frameworks.

Braiding of knowledge streams

The component model of reading (Aaron et al., 2008) was originally developed to guide teachers’ interventions for children with learning disabilities. It highlighted that, in addition to focusing on teaching children the necessary cognitive skills for reading and writing (cognitive component of the model), other areas also require direct attention. Aaron et al. (2008) discussed how a child’s home and class-learning environment, culture and home language need to be considered (ecological component of the model). In addition, they discussed the importance of reading interventions for addressing children’s motivation and interest in learning to read, their self-efficacy and teacher expectations (psychological component of the model). Variables across these domains can account for a significant proportion of the variance in children’s early reading achievement (Ortiz et al., 2012). In developing BSLA, we extended this earlier work. Rather than focusing on these components individually, from an intervention perspective for struggling readers, we considered the braiding of these influences on children’s learning from a strengths-based perspective so as to facilitate literacy success in all learners.

Alansari et al. (2022) demonstrated the importance of understanding how positive ecological and psychological influences assist Indigenous learners to thrive and succeed in education. In their study, they examined the social-psychological influences on school success for Māori and Pacific students (n=5843), Pacific whānau members (n=362) and Māori teachers (n=311) from 102 schools across New Zealand. Key findings from the study included the importance of the following areas to students’ success: strengths-based and culturally enhancing learning environments; aspiration and ambitious learning expectations; teaching practices that are contextually unique to the needs of Māori and Pacific students; strong and positive home–school partnerships; and students having networks of support and role models that embody success.

Knowledge from these streams of psychological, ecological and cognitive influence on children’s learning informed the development of the BSLA. We drew upon research from published scientific studies that included differing research methodologies and diverse populations. We also drew on Indigenous knowledge, particularly paying attention to reports, debate and critiques related to facilitators of success for Māori and Pacific learners within the New Zealand context. This is summarised in the section below and illustrated in Figure 8.1.

Figure 8.1: Braiding streams of knowledge in culturally responsive ways, to facilitate children’s literacy success

Slide from the BSLA development, reproduced with permission of the

Child Well-being Research Institute

Ecological knowledge stream

Knowledge related to two important ecological influences on children’s literacy acquisition particularly influenced the development of BSLA:

1. authentic engagement with children’s family; and

2. culturally inclusive learning environments.

Each of these influences is summarised below.

Family engagement

The critical importance of engaging families in their children’s literacy learning is well understood (Bus et al., 1995; Higgins and Katsipataki, 2015; Sénéchal and Young, 2008). Important findings related to the engagement of Indigenous and culturally diverse families particularly influenced the BSLA development. Indigenous families’ equitable access to evidence-based knowledge about their children’s learning is regularly constrained and complicated by a range of dominant cultural, personal, social and structural factors that intersect (Gerlach et al., 2017; Grace and Trudgett, 2012; Hall et al., 2015; Sianturi et al., 2022). Grace and Trudgett (2012) asserted that many Indigenous families, when attempting to engage in the educational experiences of their children, may see the education context as a purveyor of a dominant macro-culture. Indigenous families, as well as migrant families, may feel they are judged unfairly because of their preferred cultural ways of communicating and their child-rearing practices, which may differ from those of the dominant group. Grace and Trudgett suggested that many Indigenous families withdraw from engaging in educational settings, as they do not feel a sense of cultural connectedness or belonging.

Understanding facilitators of successful family engagement is therefore critical to the implementation of large-scale early literacy initiatives. The work of several research groups, both within New Zealand and internationally, has contributed to the advancement of knowledge related to facilitators of authentic engagement (for example, Bishop and Glynn, 1999; Gerlach et al., 2017; Lowe et al., 2019; Macfarlane and Macfarlane, 2015; Zhang, 2015).

Three themes that have emerged from recent research are:

1. Leadership that demonstrates commitment to change: A first step to successful engagement for some families may be overcoming mistrust in education systems. Understanding the historical elements that have led to some families’ suspicion of being involved in educational settings is important. School leaders, teachers, educators and researchers need to reflect on their own possible personal biases and positions of privilege prior to engaging with families. Change or enhancement to current practices requires leadership to:

a. advocate for culturally inclusive and responsive processes to support families’ engagement in school activities; and

b. demonstrate commitment to bringing about sustained change.

2. Positive school, home and community partnerships: Teachers and other professionals need to demonstrate willingness to reach out and build relationships in culturally appropriate ways. Building relationships, both with families and with cultural leaders in communities that support families, is important. Families need to feel a sense of belonging and inclusion in their children’s learning. They need equitable access to quality supports and resources that support their children’s learning. Once trust is gained, working together with family and community to co-construct culturally inclusive learning environments is important, to guide sustainable approaches for family engagement.

3. Building teacher knowledge: Teachers may need support in developing cultural confidence and competence in engaging with families from diverse cultural backgrounds, and in implementing culturally responsive teaching practices. When teachers, literacy specialists, speech-language therapists and others supporting children’s literacy learning demonstrate that they value a family’s culture, identity and language, they help facilitate successful family engagement.

Evidence from the research findings related to authentic family engagement needs to be braided with local community knowledge. Large-scale implementation of early literacy initiatives, therefore, must build in flexibility to account for local contexts and local knowledge. Adherence to strict, universal implementation of a pre-planned family oral-language or literacy-engagement strategy is likely to privilege families with resources and supports to adapt to the school’s criteria. Rather, the school needs to adapt and respond to their community context, to help foster more inclusive engagement.

The BSLA developed a flexible whānau-engagement strategy, based on the research evidence. Several features support inclusive and authentic engagement. Teachers are encouraged to offer two workshops to children’s whānau within the early weeks of BSLA teaching (that is, the first ten weeks). The workshops offer practical suggestions on how whānau can support their children’s oral-language and reading development. Quality workshop content is provided in a format that can be adapted to suit community needs and time available. School communities are encouraged to maximise whānau engagement by, for example, offering workshops at various times to suit parents’ schedules and as part of other school whānau events; providing food and childcare options; or offering online as well as face-to-face options. BSLA includes automated reporting of children’s progress in a format that teachers can easily adapt for their students’ whānau. Weekly home updates are automatically generated, to allow teachers to keep whānau informed of BSLA weekly literacy class activities and ideas for aligned home activities. All home materials are designed to be adapted to suit school and community needs. Through the BSLA, professional learning and development, teachers have access to a range of resources to support their personal development in engaging with whānau in culturally responsive ways.

Culturally responsive learning environment

A second important research domain within the ecological stream of influence on children’s learning relates to creating a culturally responsive learning environment. Culturally responsive practice refers to teaching, interacting and working with students from diverse cultural backgrounds in a manner that acknowledges, respects and incorporates their cultural beliefs, values and practices (Gillispie, 2021; Hyter and Salas-Provance, 2021; Ladson-Billings, 1995; Macfarlane, 2004). This approach involves creating an inclusive and welcoming teaching environment that promotes equitable learning opportunities and engages all individuals in the learning process. Culturally responsive practices involve incorporating culturally relevant materials, acknowledging students’ cultural identities and using instructional strategies that connect to students’ cultural experiences. Other related terms in the literature – such as culturally relevant, culturally sensitive, culturally informed or culturally sustaining practices – may also be used to describe literacy teaching practices that embrace these concepts of cultural inclusion (for example, Kelly et al., 2021).

Creating culturally responsive learning environments for children has long been advocated. Over 30 years ago, Gloria Ladson-Billings (1992) wrote in relation to literacy instruction for African-American students:

The compelling issue is the development of a culturally relevant approach to teaching in general that fosters and sustains the students’ desire to choose academic success … (p 313)

Her statement is still highly relevant to today’s debates around literacy instruction. In large-scale-implementation MTSS frameworks, we must consider not only the teaching content but also the teaching environments in which the instruction is being delivered. The education gap between Māori and non-Māori in the New Zealand context reflects the inequities in education experienced by Indigenous learners worldwide. Culturally inclusive teaching environments that promote equity, inclusion and respect for diversity in all aspects of life have been identified as critical to foster Māori and other Indigenous learners’ successful academic achievement (Berryman and Eley, 2017; Richards, 2017; Webber and Macfarlane, 2020). Culture is inseparable from understanding identity. It shapes us as individuals, it teaches us through values, it shapes our behaviours and how we see ourselves as learners, it gives us language toexpress ourselves. Culture also offers a rich immersion in cultural epistemology. For Māori, that is a world of kawa (customs), tikanga (traditions) and mātauranga (ancestral knowledge) that supports intergenerational transmission of culture, values and language.

Internationally, the need for pre-service education – as well as increased professional learning and development (PLD) for teachers and other education professionals in creating learning environments that value children’s culture, language and identity – has been highlighted (Bishop and Berryman, 2010; Gay, 2002; Hoover and Soltero-González, 2018). Characteristics of effective PLD for teachers have emerged from the research (for example, see Darling-Hammond, 2017). However, PLD to support teachers and literacy specialists in creating culturally responsive learning environments is in its infancy. Cantrell and colleagues (2022) are one of the few research groups to examine PLD in culturally responsive teaching practices on children’s reading achievement, using a quasi-experimental design. In their study, 21 kindergarten to grade-8 teachers in three United States school districts were assigned to receive PLD over the course of a year. Seventeen teachers in the same school districts volunteered to be in the wait-list control group. The PLD group received comprehensive support in developing their culturally responsive teaching practices, including workshops, in-class coaching, mentoring and teaching demonstrations. In addition, they were provided with the opportunity to undertake a graduate certificate in teaching for diversity. Data analyses indicated that teachers who received the PLD showed significantly greater proficiency in culturally responsive practices than the control group. This improvement coincided with significantly higher performance in their students’ reading achievement, compared to a matched group of students in classes where teachers had not undertaken the PLD.

In the development of PLD for teachers and literacy specialists involved in BSLA, we braided together knowledge gained from kaupapa Māori research, recommendations from discussions in the literature related to creating culturally responsive learning environments, and findings related to effective PLD strategies and change-process strategies, to support sustained change in teaching practice. We integrated into teachers’ and literacy specialists’ PLD opportunities for them to develop their own cultural confidence and competence through their use of the Hikairo Schema for primary teachers (Ratima et al., 2020). This is a framework designed to support and empower New Zealand educators to improve outcomes for Māori students, by developing culturally responsive practices. It provides practical strategies for incorporating te reo Māori, tikanga Māori and mātauranga Māori into the daily routines of schooling. The schema aims to bridge the gap from current practice to culturally inclusive environments that accelerate student achievement by identifying and utilising the strengths of all students.

The schema is drawn from Māori culture in ways that can benefit both Māori and non-Māori students. It encourages teachers to reflect upon and critique teaching strategies that work for Māori. Three key aspects underpin the schema components:

1. Balance of power: Building students’ self-efficacy, confidence and abilities to contribute to decision-making in their learning.

2. Scaffolding learning: Providing appropriate supports and scaffolds to ensure children experience learning success, yet still meet aspirational learning goals.

3. Relevance of learning: Ensuring learning is aligned with the students’ values, as well as their cultural and personal identities.

It is recognised within BSLA that enhancing culturally inclusive learning environments that support children’s literacy success requires ongoing support over a period of time. School and community leaders, families, teachers, literacy specialists and students will all contribute to sustaining the necessary enhancements to current practices.

Psychological knowledge stream

Aaron and Joshi (Aaron et al., 2008) highlighted the need to consider psychological influences of children’s reading development when designing reading interventions. Children’s motivation and interest in reading, their self-efficacy, as well as teacher expectations for students’ reading achievement all need to be considered. Within BSLA, we address this need through a strengths-based framework. We have braided together knowledge advanced from culturally responsive and strengths-based approaches to supporting engagement in learning for Māori and other Indigenous cultures. Strengths-based approaches focus on what children can achieve, and value students’ efforts and learning potential (Fenton et al., 2015; Galloway et al., 2020; Lee- James and Washington, 2018; Schlechter et al., 2019). They are a core aspect of fostering culturally responsive learning environments and engaging whānau in children’s learning. There are several features to the strengths-based approach of BSLA, as depicted in Figure 8.2 (see Gillon et al. (2023) for further discussion). Features include:

• Proactive approach: The BSLA framework is focused on a proactive approach. Right from the outset of schooling, teachers focus on facilitating success for all children, through high-quality and research-informed tiers of support.

• Positive learning experiences: Scaffolding and positive engagement-teaching strategies promote positive learning experiences. Teachers’ attention is focused on encouraging, praising and acknowledging students’ efforts and supporting their sense of learning achievement.

• Constructive reporting: BSLA assessment-monitoring data focuses teachers’ attention on celebrating what children can achieve and their next steps for learning. Teachers are encouraged to share children’s data with whānau in positive ways that respect and value both children’s and whānau effort.

• Positive collaborations: The BSLA model provides teachers with in-class coaching and mentoring through literacy specialists or speech-language therapists, as well as mentors from the BSLA team. A strengths-based approach to sharing and valuing expertise amongst these professionals is fostered within BSLA.

• Wellbeing focus: Building positive collaborations with whānau, community leaders and health professions, to support children’s health and wellbeing is important to maximise children’s learning opportunities in the classroom.

• Whānau engagement: Strengths-based language and approaches to engaging whānau in their children’s learning is a critical aspect of the BSLA.

• Culturally responsive: Children’s culture, language and identity are viewed as strengths that they bring to the BSLA learning activities.

Figure 8.2: Key elements of the Better Start Literacy Approach strengths-based framework

Reproduced with permission of the Child Well-being Research Institute

Cognitive knowledge stream

Robust research evidence over many decades has clearly demonstrated the critical cognitive skills that are essential to literacy acquisition (for example, phonological awareness, alphabet knowledge, morphological awareness, vocabulary, oral-language comprehension and oral narrative skills) (Carlo et al., 2004; Catts et al., 2015; Gillon, 2018; Reese et al., 2010; Roth et al., 2002; Ruan et al., 2018). The theoretical framework that underpins the development of cognitive skills taught within BSLA is called the ‘simple view of reading’ (see Hoover and Tunmer (2018) for a recent discussion). Teachers are supported with BSLA daily lesson plans, to engage children in structured and explicit teaching activities that advance their word-recognition skills as well as their language comprehension. In addition, children participate in small-group reading sessions using readers that follow a structured phonic scope and sequence plan to support their reading success. Data from controlled pilot studies suggested the BSLA is more effective than other types of literacy instruction in advancing children’s alphabet knowledge, phonological awareness, word reading and spelling skills, and is effective in developing their oral-language skills (Gillon et al., 2019; 2020; 2023).

A unique aspect of BSLA is the braiding of knowledge in relation to cognitive skills with both ecological and psychological influences on children’s reading development. Examples of this braiding are the use of culturally relevant resources and the integration of place-based education strategies.

Culturally relevant resources

Having access to and using culturally relevant resources in the classroom is an essential aspect of culturally responsive practice. Culturally relevant resources are materials that reflect the cultural backgrounds and experiences of students and include books as well as videos, music, art and other forms of media. By incorporating culturally relevant resources, teachers support students to feel more connected to the curriculum and engaged in the learning process (Bishop and Berryman, 2010; Waiti, 2018). These resources can also promote a sense of pride and identity in students, especially for those from historically marginalised or under-represented groups, like Māori (Macfarlane, 2004). Research has shown that the use of culturally relevant resources can improve academic achievement and promote positive identity and self-esteem among students (Ladson-Billings, 1995). Furthermore, it can enhance cross-cultural understanding and appreciation, which is crucial for developing global citizenship and social cohesion (Banks, 2004).

The BSLA’s culturally relevant teaching resources are designed to reflect modern-day New Zealand and embody the bicultural aspirations of the education sector. These resources incorporate te reo Māori but go further to draw on te ao Māori contexts. This intentional design is evident not only in the text and illustrations of storybooks and children’s readers used within BSLA, but also in the teaching notes and lesson plans that provide scaffolding for teachers.

Incorporating Māori vocabulary in children’s readers and literacy learning materials is a vital aspect of promoting and supporting the use of te reo Māori in education. Tau Mai Te Reo | The Māori Language in Education Strategy (Ministry of Education, 2023) highlights the importance of creating an environment where te reo Māori can be ‘seen, read, heard and spoken’ in educational settings. This includes the integration of Māori words in English-medium classroom resources.

BSLA incorporates the use of a new reading series for young children developed for the New Zealand education context: Ready to Read Phonics Plus (Arrow et al., 2021). The series incorporates a small selection of everyday Māori words into the book text. This approach aligns with the vision of the government’s Māori Language Strategy: to have Māori language used widely by Māori and its value appreciated by all New Zealanders.

Incorporating Māori vocabulary into children’s reading experiences from an early age helps bridge the gap between learning to read in English and using Māori language in the community. It also provides an opportunity to incorporate Māori students’ funds of knowledge into the language of school reading materials, which contributes to a sense of cultural belonging and identity (Toppel, 2015). The intentional inclusion of Māori vocabulary in readers and learning materials by the BSLA affirms Māori learners as Māori and supports language revitalisation efforts in New Zealand.

Place-based education

Place-based education is a teaching approach that supports students making connections between curriculum learning activities and the physical location of their learning space (Yemini et al., 2023). Place-based education has been used to incorporate Māori perspectives and knowledge into the New Zealand curriculum. Place-based education can help to promote cultural understanding and awareness among communities, while also providing opportunities for Māori students to see and learn through their Indigenous knowledge. Penetito (2009) has asserted that placed-based learning also provides important opportunities that help address issues of cultural disconnection, and promotes a sense of belonging and identity among Māori students. Different mediums like whakapapa (genealogy), kapa haka (traditional performing arts), mahinga kai (natural resource gathering sites) and pūrākau (Māori legends or stories), as well as learning about local environments such as rivers, forests and mountains, can set the context for learning. As students learn about the ecological, spiritual and cultural significance of these environments, they are also being immersed in Māori cultural values such as kaitiakitanga (guardianship), whanaungatanga (connection building) and manaakitanga (empathy).

Pūrākau can be an effective way in which to support teachers accessing culturally relevant place-based resources. Lee (2009) discussed Māori use of pūrākau as a crucial means to transmit traditional values, promote communication and facilitate the exchange of ideas, knowledge, perspectives and experiences. Since engaging with shared narratives relies heavily on oral language and listening comprehension – essential skills for reading development – pūrākau are a useful resource within school and home-literacy activities.

To support placed-based education strategies within BSLA, a pilot study (Child Well-being Research Institute, 2022) was undertaken in partnership with one of Canterbury’s rūnanga (tribal councils), Te Taumutu Rūnanga. This partnership saw opportunity to braid together pūrākau practices and English-medium literacy practices to enhance learning for all. The project involved working with leaders within the rūnunga to adapt existing pūrākau that were written for older students. Adaptations included a writing style, story length and content that was suitable for young four-to-six-year-old children. Youth within the Te Taumutu community were supported by their local artists to illustrate the pūrākau. The storybooks depict three different pūrākau that are significant to Taumutu, including Ruru and the Giant Pouākai, The Creation of Tuna and Taniwha and the Rakaia Gorge (Child Well-being Research Institute, 2022).

The chair of Te Taumutu Rūnanga described how these pūrākau, which were accessible to all local early childhood centres and primary schools, are beneficial to the education and wellbeing of children in their area. They demonstrate to young Māori that their culture and background is valued (Child Well-being Research Institute, 2022). The development of these pūrākau has several benefits, including meeting the aspirations of local Māori, supporting local teachers to access place-based culturally relevant resources and, finally, immersing local youth in connecting with community in culturally sustaining ways.

Summary

Large-scale implementation of effective, research-based early literacy initiatives is essential to addressing current education inequities. One such initiative being implemented in junior-school classes throughout New Zealand is the Better Start Literacy Approach. He Awa Whiria proved a useful framework to guide the development of this approach. Braiding together knowledge and research findings related to the ecological, psychological and cognitive influences on children’s reading development has led to a strengths-based and culturally responsive approach for high-quality early literacy instruction. Evidence suggests the approach is effective in enhancing children’s early literacy success. The use of He Awa Whiria to guide the BSLA has supported the power of literacy to strengthen the culture, language and identity for all learners.

![]()

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to acknowledge their colleagues within the Better Start Literacy Approach (BSLA) team. In particular, we acknowledge the leadership of Professor Brigid McNeill, co-lead developer of BSLA, Dr. Amy Scott and Tufulasi Taleni within BSLA development. We also acknowledge the support of teachers, literacy specialists, school and community leaders, families and children who are all involved in advancing the successful implementation of BSLA throughout New Zealand.

![]()

References

Aaron, P.G., Malatesha Joshi, R., Gooden, R. & Bentum, K.E. (2008), ‘Diagnosis and treatment of reading disabilities based on the component model of reading: An alternative to the discrepancy model of LD’, Journal of Learning Disabilities, 41(1), 67–84: https://doi.org/10.1177/0022219407310838

Alansari, M., Webber, M., Overbye, S., Tuifagalele, R. & Edge, K. (2022), Conceptualising Māori and Pasifika Aspirations and Striving for Success (COMPASS) (New Zealand Council for Educational Research).

Arias-Gundín, O. & Llamazares, A.G. (2021), ‘Efficacy of the RtI model in the treatment of reading learning disabilities’, Education Sciences, 11(5), Article 209: https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci11050209

Arrow, A., Gillon, G., McNeill, B. & Scott, A. (2021), ‘Ready to Read Phonics Plus Project. End of year report November 2021’: [PDF] https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5d5e600b9630870001cf8cb9/t/621594b77b30b6044527b2f8/1645581531028/Ready+to+Read+Phonics+Plus+Report.pdf

Banks, J.A. (2004), ‘Teaching for social justice, diversity, and citizenship in a global world’, The Educational Forum, 68(4), 296–305: https://doi.org/10.1080/00131720408984645

Bell, Y.R. & Clark, T.R. (1998), ‘Culturally relevant reading material as related to comprehension and recall in African American children’, Journal of Black Psychology, 24(4), 455–75: https://doi.org/10.1177/00957984980244004

Berryman, M. & Eley, E. (2017), ‘Succeeding as Māori: Māori students’ views on our stepping up to the Ka Hikitia challenge’, New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies, 52(1), 93–107.

Better Start National Science Challenge: www.abetterstart.nz/Bishop, R. & Berryman, M. (2010), ‘Te kotahitanga: Culturally responsive professional development for teachers’, Teacher Development, 14(2), 173–87: https://doi.org/10.1080/13664530.2010.494497

Bishop, R. & Glynn, T. (1999), Culture Counts: Changing power relations in education, (Palmerston North: Dunmore Press).

Bus, A.G., Van Ijzendoorn, M.H. & Pellegrini, A.D. (1995), ‘Joint book reading makes for success in learning to read: A meta-analysis on intergenerational transmission of literacy’, Review of Educational Research, 65(1), 1–21.

Cantrell, S.C., Sampson, S.O., Perry, K.H. & Robershaw, K. (2022), ‘The impact of professional development on inservice teachers’ culturally responsive practices and students’ reading achievement’, Literacy Research and Instruction, 62(3), 233–59: https://doi.org/10.1080/19388071.2022.2130117

Carlo, M.S., August, D., Mclaughlin, B., Snow, C.E., Dressler, C., Lippman, D.N., Lively, T.J. & White, C.E. (2004), ‘Closing the gap: Addressing the vocabulary needs of English-language learners in bilingual and mainstream classrooms’, Reading Research Quarterly, 39(2), 188–215: https://doi.org/10.1598/rrq.39.2.3

Catts, H.W., Nielsen, D.C., Bridges, M.S., Liu, Y.S. & Bontempo, D.E. (2015), ‘Early identification of reading disabilities within an RTI framework’, Journal of Learning Disabilities, 48(3), 281–97: https://doi.org/10.1177/0022219413498115

Child Well-being Research Institute (2022), ‘Books about Māori ancestral stories created for Canterbury children’, in Nurturing Research Excellence to Support Children’s Holistic Well-Being: Year in review 2022 (32–33), Child Well-being Research Institute, University of Canterbury: [PDF] https://www.canterbury.ac.nz/content/dam/uoc-main-site/documents/pdfs/reports/CWRI-Year-in-Review-2022.pdf.coredownload.pdf

Cram, F., Vette, M., Wilson, M., Vaithianathan, R., Maloney, T. & Baird, S. (2018), ‘He awa whiria – braided rivers: Understanding the outcomes from Family Start for Māori’, Evaluation Matters: https://doi.org/10.18296/em.0033

D’Aietti, K., Lewthwaite, B. & Chigeza, P. (2021), ‘Negotiating the pedagogical requirements of both explicit instruction and culturally responsive pedagogy in Far North Queensland: Teaching explicitly, responding responsively’, Australian Journal of Indigenous Education, 50(2), 312–19: https://doi.org/10.1017/jie.2020.5

Darling-Hammond, L. (2017), ‘Teacher education around the world: What can we learn from international practice?’, European Journal of Teacher Education, 40(3), 291–309: https://doi.org/10.1080/02619768.2017.1315399

Duckworth, F., Gibson, M., Macfarlane, S. & Macfarlane, A. (2021), ‘Mai i te ao rangatahi ki te ao pakeke ka awatea: A study of Māori student success revisited’, AlterNative, 17(1), 3–14: https://doi.org/10.1177/1177180121995561

Fenton, A., Walsh, K., Wong, S. & Cumming, T. (2015), ‘Using strengths-based approaches in early years practice and research’, International Journal of Early Childhood, 47(1), 27–52: https://doi.org/10.1007/s13158-014-0115-8

Fien, H., Chard, D.J. & Baker, S.K. (2021), ‘Can the evidence revolution and multitiered systems of support improve education equity and reading achievement?’, Reading Research Quarterly, 56(S1), S105–18: https://doi.org/10.1002/rrq.391

Galloway, R., Reynolds, B. & Williamson, J. (2020), ‘Strengths-based teaching and learning approaches for children: Perceptions and practices’, Journal of Pedagogical Research, 4(1), 31–45.

Gay, G. (2002), ‘Preparing for culturally responsive teaching’, Journal of Teacher Education, 53(2), 106–16.

Gerlach, A.J., Browne, A.J. & Greenwood, M. (2017), ‘Engaging Indigenous families in a community-based Indigenous early childhood programme in British Columbia, Canada: A cultural safety perspective’, Health & Social Care in the Community, 25(6), 1763–73.

Gillispie, M. (2021), ‘Culturally responsive language and literacy instruction with native American children’, Topics in Language Disorders, 41(2), 185–98: https://doi.org/10.1097/TLD.0000000000000249

Gillon, G. (2018) Phonological Awareness: From research to practice (2nd edn.), (New York: Guilford Press).

Gillon, G. & Macfarlane, A.H. (2017), ‘A culturally responsive framework for enhancing phonological awareness development in children with speech and language impairment’, Speech, Language and Hearing, 20(3), 163–73: https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/2050571X.2016.1265738

Gillon, G., McNeill, B., Denston, A., Scott, A. & Macfarlane, A. (2020), ‘Evidence-based class literacy instruction for children with speech and language difficulties’, Topics in Language Disorders, 40(4), 357–74: https://doi.org/10.1097/TLD.0000000000000233

Gillon, G., McNeill, B., Scott, A., Arrow, A., Gath, M. & Macfarlane, A. (2023), ‘A better start literacy approach: Effectiveness of Tier 1 and Tier 2 support within a response to teaching framework’, Reading and Writing, 36(3), 565–98: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-022-10303-4

Gillon, G., McNeill, B., Scott, A., Denston, A., Wilson, L., Carson, K. & Macfarlane, A.H. (2019), ‘A better start to literacy learning: Findings from a teacher-implemented intervention in children’s first year at school’, Reading and Writing, 32(8), 1989–2012: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-018-9933-7

Goldenberg, C. (2013), ‘Unlocking research into English learners: What we know – and don’t yet know – about effective instruction’, American Educator, 37(2), 4–11.

Gonzalez, J.E., Durán, L., Linan-Thompson, S. & Jimerson, S.R. (2022), ‘Unlocking the promise of multitiered systems of support (MTSS) for linguistically diverse students: Advancing science, practice, and equity’, School Psychology Review, 51(4), 387–91: https://doi.org/10.1080/2372966X.2022.2105612

Grace, R. & Trudgett, M. (2012), ‘It’s not rocket science: The perspectives of Indigenous early childhood workers on supporting the engagement of Indigenous families in early childhood settings’, Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 37(2), 10–18.

Hall, N., Hornby, G. & Macfarlane, S. (2015), ‘Enabling school engagement for Māori families in New Zealand’, Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24, 3038–46.

Higgins, S. & Katsipataki, M. (2015), ‘Evidence from meta-analysis about parental involvement in education which supports their children’s learning’, Journal of Children’s Services, 10(3), 280–90: https://doi.org/10.1108/JCS-02-2015-0009

Hoover, J.J. & Soltero-González, L. (2018), ‘Educator preparation for developing culturally and linguistically responsive MTSS in rural community elementary schools’, Teacher Education and Special Education, 41(3), 188–202: https://doi.org/10.1177/0888406417753689

Hoover, W.A. & Tunmer, W.E. (2018), ‘The simple view of reading: Three assessments of its adequacy’, Remedial and Special Education, 39(5), 304–12: https://doi.org/10.1177/0741932518773154

Hyter, Y.D. & Salas-Provance, M.B. (2021) Culturally Responsive Practices in Speech, Language, and Hearing Sciences (2nd edn.), (San Diego, CA: Plural Publishing).

Kelly, L.B., Wakefield, W., Caires-Hurley, J., Kganetso, L.W., Moses, L. & Baca, E. (2021), ‘What is culturally informed literacy instruction? A review of research in P–5 contexts’, Journal of Literacy Research, 53(1), 75–99: https://doi.org/10.1177/1086296X20986602

Ladson-Billings, G. (1992), ‘Reading between the lines and beyond the pages: A culturally relevant approach to literacy teaching’, Theory Into Practice, 31(4), 312–20: https://doi.org/10.1080/00405849209543558

Ladson-Billings, G. (1995), ‘Toward a theory of culturally relevant pedagogy’, American Educational Research Journal, 32(3), 465–91.

Lee, J. (2009), ‘Decolonising Māori narratives: Pūrākau as a method’, MAI Review 2.

Lee-James, R. & Washington, J.A. (2018), ‘Language skills of bidialectal and bilingual children: Considering a strengths-based perspective’, Topics in Language Disorders, 38(1), 5–26: https://doi.org/10.1097/TLD.0000000000000142

Linan-Thompson, S., Ortiz, A. & Cavazos, L. (2022), ‘An examination of MTSS assessment and decision making practices for English learners’, School Psychology Review, 51(4), 484–97: https://doi.org/10.1080/2372966X.2021.2001690

Lowe, K., Harrison, N., Tennent, C., Guenther, J., Vass, G. & Moodie, N. (2019), ‘Factors affecting the development of school and Indigenous community engagement: A systematic review’, The Australian Educational Researcher, 46(2), 253–71.

Macfarlane, A. (2004). Kia Hiwa Ra!: Listen to culture: Māori students’ plea to educators, New Zealand Council for Educational Research.

Macfarlane, A. & Macfarlane, S. (2015), ‘Education, psychology and culture: Towards synergetic practices’, Knowledge Cultures, 3(2), 66–81.

Macfarlane, A.H., Macfarlane, S. & Webber, M. (2015), Sociocultural Realities: Exploring new horizons (Christchurch: Canterbury University Press).

Maessen, S.E., Taylor, B.J., Gillon, G., Moewaka Barnes, H., Firestone, R., Taylor, R.W., Milne, B., Hetrick, S., Cargo, T., McNeil, B. & Cutfield, W. (2023), ‘A better start national science challenge: Supporting the future wellbeing of our tamariki. E tipu, e rea, mō ngā rā o tō ao: Grow tender shoot for the days destined for you’, Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand, 53(5), 673–96: https://doi.org/10.1080/03036758.2023.2173257

Ministry of Education (2023), Tau Mai Te Reo | The Māori Language in Education Strategy (English): www.education.govt.nz/our-work/overall-strategies-and-policies/tau-mai-te-reo/

Ortiz, M., Folsom, J.S., Otaiba, S.A., Greulich, L., Thomas-Tate, S. & Connor, C.M. (2012), ‘The componential model of reading: Predicting first grade reading performance of culturally diverse students from ecological, psychological, and cognitive factors assessed at kindergarten entry’, Journal of Learning Disabilities, 45(5), 406–17: https://doi.org/10.1177/0022219411431242

Penetito, W. (2009), ‘Place-based education: Catering for curriculum, culture and community’, New Zealand Annual Review of Education, 18(2008), 5–29.

Ratima, M., Smith, J., Macfarlane, A. & Macfarlane, S. (2020), The Hikairo Schema for Primary: Culturally responsive teaching and learning (New Zealand Council for Educational Research).

Reese, E., Suggate, S., Long, J. & Schaughency, E. (2010), ‘Children’s oral narrative and reading skills in the first three years of reading instruction’, Reading and Writing, 23, 627–44.

Relyea, J.E., Rich, P., Kim, J.S. & Gilbert, J.B. (2023), ‘The COVID-19 impact on reading achievement growth of Grade 3–5 students in a U.S. urban school district: Variation across student characteristics and instructional modalities’, Reading and Writing, 36(2), 317–46: https://doi.org/10.1007/s11145-022-10387-y

Richards, S.M. (2017), ‘A critical analysis of a culturally responsive pedagogy: Towards improving Māori achievement’ (Master’s thesis, University of Waikato).

Ross, C.E. & Mirowsky, J. (2011), ‘The interaction of personal and parental education on health’, Social Science & Medicine, 72(4), 591–99.

Roth, F.P., Speece, D.L. & Cooper, D.H. (2002), ‘A longitudinal analysis of the connection between oral language and early reading’, Journal of Educational Research, 95(5), 259–72.

Ruan, Y., Georgiou, G.K., Song, S., Li, Y. & Shu, H. (2018), ‘Does writing system influence the associations between phonological awareness, morphological awareness, and reading? A meta-analysis’, Journal of Educational Psychology, 110(2), 180.

Schlechter, A.D., O’Brien, K.H. & Stewart, C. (2019), ‘The positive assessment: A model for integrating well-being and strengths-based approaches into the child and adolescent psychiatry clinical evaluation’, Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 28(2), 157–69: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chc.2018.11.009

Sénéchal, M. & Young, L. (2008), ‘The effect of family literacy interventions on children’s acquisition of reading from kindergarten to grade 3: A meta-analytic review’, Review of Educational Research, 78(4), 880–907.

Sianturi, M., Lee, J.S. & Cumming, T.M. (2022), ‘A systematic review of Indigenous parents’ educational engagement’, Review of Education, 10(2), e3362.

Sissons, J. (2000), ‘The post-assimilationist thought of Sir Apirana Ngata: Towards a genealogy of New Zealand biculturalism’, New Zealand Journal of History, 34(1), 47–59.

Tomaszewski, W., Zajac, T., Rudling, E., te Riele, K., McDaid, L. & Western, M. (2022), ‘Uneven impacts of COVID-19 on the attendance rates of secondary school students from different socioeconomic backgrounds in Australia: A quasi-experimental analysis of administrative data’, Australian Journal of Social Issues: https://doi.org/10.1002/ajs4.219

Toppel, K. (2015), ‘Enhancing core reading programs with culturally responsive practices’, The Reading Teacher, 68(7), 552–59.

United Nations (2015), Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development: [PDF] https://sdgs.un.org/sites/default/files/publications/21252030%20Agenda%20for%20Sustainable%20Development%20web.pdf

Waiti, J. (2018), ‘Māori pedagogies: A framework for culturally responsive practice in Aotearoa New Zealand’, in S.L. Black & P.B. Milfont (eds), Culture, Identity, and Indigenous Psychology: Understanding the complexities (29–46), (New York: Springer).

Webber, M. & Macfarlane, A. (2020), ‘Mana tangata: The five optimal cultural conditions for Māori student success’, Journal of American Indian Education, 59(1), 26–49.

Yemini, M., Engel, L. & Ben Simon, A. (2023), ‘Place-based education: A systematic review of literature’, Educational Review: https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2023.2177260

Zhang, Q. (2015), ‘Defining ‘meaningfulness’: Enabling preschoolers to get the most out of parental involvement’, Australasian Journal of Early Childhood, 40(4), 111–20.

- See the full advice from Sir Apirana Ngata on the A Better Start National Science Challenge website: www.abetterstart.nz/ ↵