4 Journey of a He Awa Whiria research programme:

Families and whānau wellbeing

Kahukore Baker

![]()

Ki ngā tōhunga o tēnei rangahau: To the experts of this research:

In te ao Māori, ‘te kōtuku rerenga tahi’ refers to ‘a white heron of a single flight’, rarely seen and highly prized – to describe and honour an individual of great standing.

Those who have contributed their mātauranga (knowledge and wisdom), their whakaaro (thoughts), their vision, their leadership and their strength of spirit to building this seminal research and development platform, have a journey more akin to the long flight of the royal albatross.

The royal albatross is a renowned ocean wanderer, travelling vast distances from its traditional lands, yet always returning to rest and create the next generation. Its flight is one of the most enigmatic features of nature. It will circumnavigate the globe through fair weather and through storms, hurricanes, searing heat and periods of calm, driven forever on by its very being. So, too, are the journeys of those who have pioneered this legacy research and development platform over many, many decades. You are the sky wanderers, the ocean voyagers and the visionaries who forever seek new horizons; without you, none of this would be possible.

You exist on both sides of the Treaty of Waitangi partnership. You have been, and are, the builders of nationhood in Aotearoa New Zealand. Without you, this fledging research programme would have no feet upon which to stand.

It is a great privilege to draw on your legacy, as we add ‘our bit’ to growing the evidence base about family and whānau wellbeing in New Zealand today.

![]()

Implementing He Awa Whiria in the Families and Whānau Wellbeing Research Programme

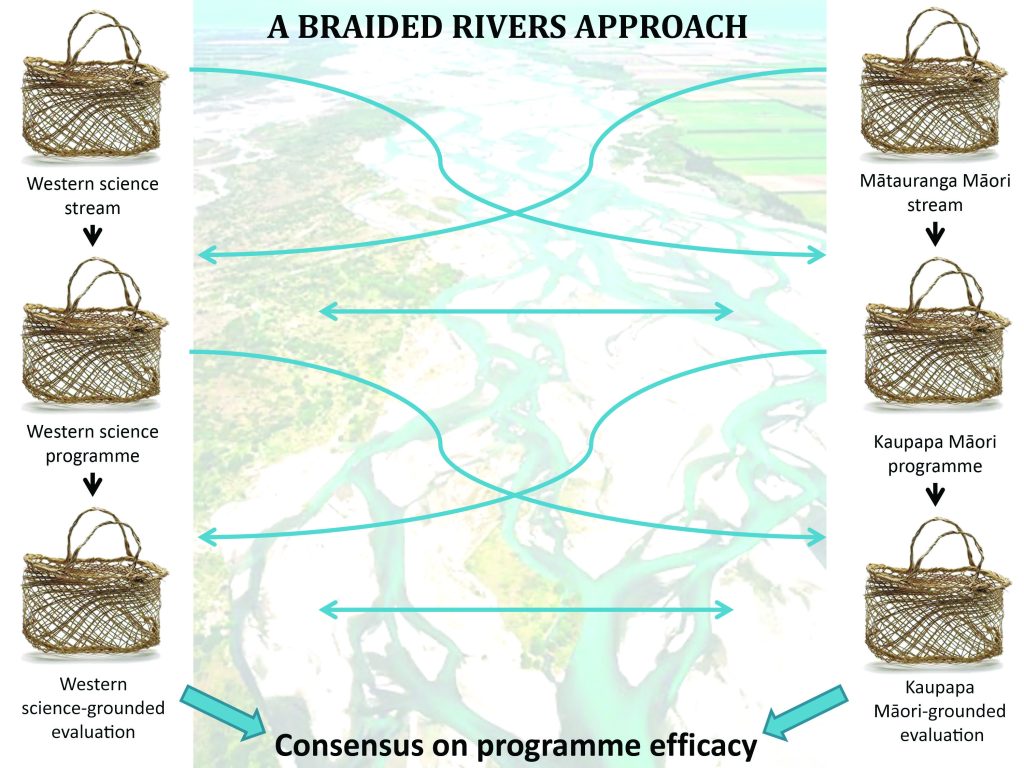

Both streams start at the same place and run beside each other in equal strength.

They come together on the riverbed and then they move away from one another.

Each stream spends more time apart than together.

In the model, when they do converge, the space created is one of learning, not assimilating.

The above definition of He Awa Whiria is an extract from the Superu (Social Policy Evaluation and Research Unit) report, Bridging Cultural Perspectives (Arago-Kemp and Hong, 2018, p 8). The report was underpinned by He Awa Whiria, the framework developed by Professor Angus Macfarlane as part of his work in the Advisory Group on Conduct Problems (see Figure 4.1). Bridging Cultural Perspectives reports the deliberations of the He Awa Whiria – Braided Rivers Advisory Group,[1] as part of a project led by Superu staff Vyletta Arago-Kemp and Bev Hong.

Figure 4.1: A model of He Awa Whiria

From AGCP, 2011 (p 64). Licensed for adaption and re-use under (CC-BY) 4.0.

This chapter charts the early opportunities, challenges, considerations and decisions made in implementing He Awa Whiria to frame the families and whānau wellbeing research as a strategic research programme. The focus is on how the two differing streams emerged. While research findings and approaches are discussed, this is done to further illustrate the richness that can evolve through a He Awa Whiria approach across family and whānau wellbeing, rather than to focus on the research itself.

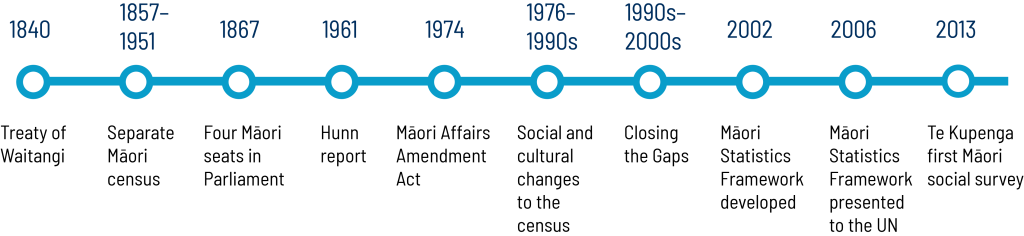

In doing so, I outline the approach’s initial use at Superu (previously known as the Families Commission) and its ongoing application in the research presented in the annual Families and Whānau Status Reports 2013–2018. However, to fully grasp the challenges we faced in this research programme, it is important to briefly traverse the historical context of the Crown collecting data on Māori, to provide background to the issues that lay before us in this task (see Figure 4.2).

Figure 4.2: Key dates in the evolution of Māori data and statistics

From Families Commission (2016) (later Superu), unpublished source. Used under licence.

The history of Māori population measures lies in colonisation and assimilation

The purpose of early data collections of the Māori population was varied. On the one hand, the development of Māori parliamentary representation required data; but another purpose was surveillance of the Māori population (Kukutai and Cormack, 2022).

Some of the earliest lists of iwi and hapū data compiled on behalf of the Crown are of the numbers of men, women and children of the hapū and iwi placed on Native Reserves following the confiscation of their lands, during and after the Land Wars of the 1860s. Those whose lands had been confiscated were often unjustly identified as “surrendered rebels” (Appendices to the Journals of the House of Representatives, 1872).

The Crown also categorised definitions of Māori identity as either ‘half-caste’ or ‘full-blood’; those perceived to be living as Europeans in European settlements were counted as ‘European’, while those living as Māori were counted as ‘Māori’ (Cormack, 2010). Assimilation persisted, with the Hunn report (1961) recommending the phasing out of ‘Māori’ as a classification in official statistics altogether.

The Māori Community Development Act 1962 and the Māori Affairs Amendment Act 1974 were landmarks in changing Māori classifications by the Crown. For the first time, any descendant of a Māori could self-identify as Māori. Later censuses included questions about Māori ethnicity, Māori descent and usage of te reo Māori.

Despite these innovations, the Crown’s practice of determining measures for, and about, the Māori population became ingrained in the ongoing development and use of Crown data.

Towards changing the Crown’s perceptions of Māori data: The Māori Statistics Framework

The need to move away from the Crown determining what data about Māori is to be valued, collected, analysed and interpreted, was at the heart of the foundational change identified in the Māori Statistics Framework.

In 2002 Statistics New Zealand developed a paper called Towards a Māori Statistics Framework (Statistics New Zealand, 2002). Led by Māori statistician Whetumarama Wereta, this ground-breaking work sought to turn the statistics the Crown gathered about Māori on its head by asking the fundamental question: What are the collective aspirations held by Māori that a Māori statistical framework should represent?

This innovative work drew on both international and national literature in its development and, in 2006, was presented to a United Nations forum on Indigenous peoples’ wellbeing (Wereta and Bishop, 2004). Internationally, Nobel laureate Amatrya Sen advocated that development should be seen as a process of expanding people’s freedom to choose and to attain the kind of life they wish to live (Wereta and Bishop, 2004). Many Indigenous peoples, by virtue of being Indigenous, are unable to choose and attain the life they wish to live; this is a consequence of colonisation with significant historical and structural injustices and inequalities resulting.

The Māori Statistics Framework used Māori-development literature, as well as the proceedings of many Māori conferences and hui (meetings) – for example, the New Zealand Māori Council and the Māori Women’s Welfare League. From this, Wereta and Bishop identified that, collectively, Māori aspired to wellbeing, and that a concept of ‘wellbeing’ needed to be defined by drawing on tikanga Māori.

The Families Commission and the Whānau Rangatiratanga research programme

The Families Commission was established under the Families Commission Act 2003, as well as under the Crown Entities Act 2004. By 2009, with Sir Meihana Durie and Sir Kim Workman as successive Māori commissioners, the organisation was well placed to establish a strong whānau direction and research programme, as set out in the Whānau Strategic Framework: 2009–2012 (Families Commission, 2012). This was the earlier work upon which the whānau wellbeing research programme was built.

The framework identified that a key role for the commission was to support whānau to achieve a state of whānau ora, or wellbeing, through engagement, social policy and research.

To support this direction, Dr. Kathie Irwin, Chief Advisor Māori, worked with the chief commissioner, the commission’s board and the Whānau Reference Group (established to advise the board) to develop a work programme, with whānau empowerment as the outcome.

What Works with Māori: What the people said

The culmination of this multi-year whānau strategic research programme was the 2013 research report What Works with Māori: What the people said (Irwin et al., 2013). Drawing on He Awa Whiria, Irwin identified the use of a kaupapa Māori and critical-theory framework to present the context, concepts, data collection and interpretation of the multi-year Whānau Rangatiratanga (whānau empowerment) research programme in the 2013 report:

The data in this study were analysed using a kaupapa Māori/critical theory framework informed by significant features of each theory. The framework adopts a ‘braided river’ approach by reading between theoretical positions derived from Western knowledge codes; in this case critical theory, as it provides for differentiated analyses of major social issues; and kaupapa Māori theory, as it integrates the Treaty of Waitangi in the framework and positions mātauranga Māori centrally. (p 24)

Following this example, the Families Commission further adopted He Awa Whiria as a model to frame other research projects. For example, an initial research project on economic hardship was reframed into two streams – a families stream and a whānau stream. The families stream included case studies to research hardship and financial behaviours across a range of New Zealand families, and the nature of the support from providers and church organisations. This was published as One Step at a Time (Couchman and Baker, 2012).

The whānau stream was strengths-based, focusing on the practices whānau rely on in times of hardship, and in engaging with agencies. This report was published as Te Pūmautanga o te Whānau: Tūhoe and South Auckland whānau (Baker et al., 2012).

He Awa Whiria frames our approach to family and whānau wellbeing

Restructuring brings annual reporting on the wellbeing of families and whānau

By 2012, discussions were underway to restructure the Families Commission. By 2014, as part of new legislative functions, the commission was required to prepare an annual report on the wellbeing of families in New Zealand. With the restructuring came a greater focus on social policy, research and evaluation, and the commission became known as Superu – the Social Policy, Evaluation and Research Unit.

With a focus on whānau rangatiratanga research and outcomes, applying He Awa Whiria to wellbeing work was the next logical step.

By definition, He Awa Whiria is a Treaty-based model for framing research about or with Māori in New Zealand. In this programme, we needed to explore:

• key conceptual and theoretical differences about wellbeing and about ‘families’ and ‘whānau’

• the different cultural, political, social and economic trajectories that have informed policy and data development on families and whānau

• the priorities that have shaped decisions about data on family and whānau, and on wellbeing.

Families and whānau are not interchangeable

In Definitions of Whānau, Lawson-Te Aho (2010) cautions against the interchangeable use of the terms ‘family’ and ‘whānau’ by policymakers, citing a resulting failure to provide authentically for whānau Māori. Lawson-Te Aho noted that criticisms arose in the Definitions of Whānau report over the fact the government used family and whānau interchangeably, stating that policymakers needed to understand the “economic role of whānau as foundational and indeed critical for the maintenance and survival of Māori culture” (p 14).

Definitions of whānau have been the subject of a significant body of work in New Zealand over some decades. As Lawson-Te Aho writes:

Smith (2000) states “there is more to kaupapa Māori than our own history under colonialism or our desires to restore Rangatiratanga. We have a different epistemological (the nature of knowledge) tradition that frames the way we see the world, the way we organise ourselves in it, the questions we ask and the solutions we seek” (p 230). This is particularly relevant to understanding the differences in interpretation and application of the cultural construct of whānau. (p 8)

Lawson-Te Aho identified that, through Māori literature, two “pre-eminent models of whānau” emerge – ‘whakapapa whānau’ and ‘kaupapa whānau’:

The two pre-eminent models of whānau from the literature are whakapapa (kinship) and kaupapa (purpose-driven) whānau. Whakapapa whānau are the more permanent and culturally authentic form of whānau. Whakapapa and kaupapa whānau are not mutually exclusive. (p 24)

In 2013, Irwin explored this further:

Whānau sit at the complex nexus between the social configuration of whānau, hapū and iwi, and the philosophical tradition articulated through Māori cultural knowledge, methods and practice. At this nexus, ‘being Māori’ is a lived reality in which whānau negotiate authentic pathways to new futures. (p 12)

Applying He Awa Whiria meant similar steps but different epistemologies

Considering the contextual terrain traversed above, it was seen as critical to the development of both streams that we understood the need for:

• two separate reference groups, one for families and one for whānau

• two separate conceptual and/or measurement frameworks, one for families and one for whānau

• different priorities in identifying relevant measures for both work streams

• significant differences in availability of whānau data compared with family data.

But don’t we still need to compare Māori families against other ethnicities?

The benefit of He Awa Whiria is that it is a Treaty-based model. As a Treaty partner, the government needs actively to protect mātauranga Māori as a taonga (treasured cultural possession) (as per Article II of the Treaty) and also to ensure Māori have the same rights to citizenship as all New Zealanders (as per Article III).

This means that Māori are represented in both the whānau and families work streams. In the whānau work stream, our research, analysis and overall interpretation of whānau data is framed within te ao Māori.

In the family stream, while the place of tangata whenua (Indigenous people of the land) is acknowledged, Māori family data is presented alongside that of other ethnicities, to form part of a whole-of-New Zealand population view. Ethnicity data is an individual characteristic. Structurally, the place of Māori data in the family stream is as individual members of the New Zealand population – an Article III approach.

While we can learn about how Māori families are faring compared with all New Zealanders by looking across the families stream, to fully understand whānau wellbeing – defined by Māori as a more culturally authentic and reliable measure – we need to turn to the whānau work stream. Finally, by looking across both streams, we gain a fuller picture of family and whānau wellbeing, highlighting key gaps in our knowledge base about whānau wellbeing that would not have been evident without a whānau work stream.

Establishment of whānau and families reference groups

The Whānau Wellbeing Reference Group[2] included experts in Māori statistics, demographics and mātauranga Māori, from the National Institute of Demographic and Economic Analysis at the University of Waikato, Mira Szászy Research Centre for Māori and Pacific Economic Development at the University of Auckland, Statistics New Zealand, and Te Puni Kōkiri (Ministry for Māori Development) and Superu Māori staff.

The Families Wellbeing Reference Group included academics and government representatives with considerable knowledge of family issues and/or who had carried out research into families and family wellbeing.

Both groups independently identified the need for frameworks to guide decision making and analysis, define ‘whānau’ and ‘family’, define whānau wellbeing and family wellbeing, and to determine potential indicators, data sources and research priorities. However, the approach of each was very different.

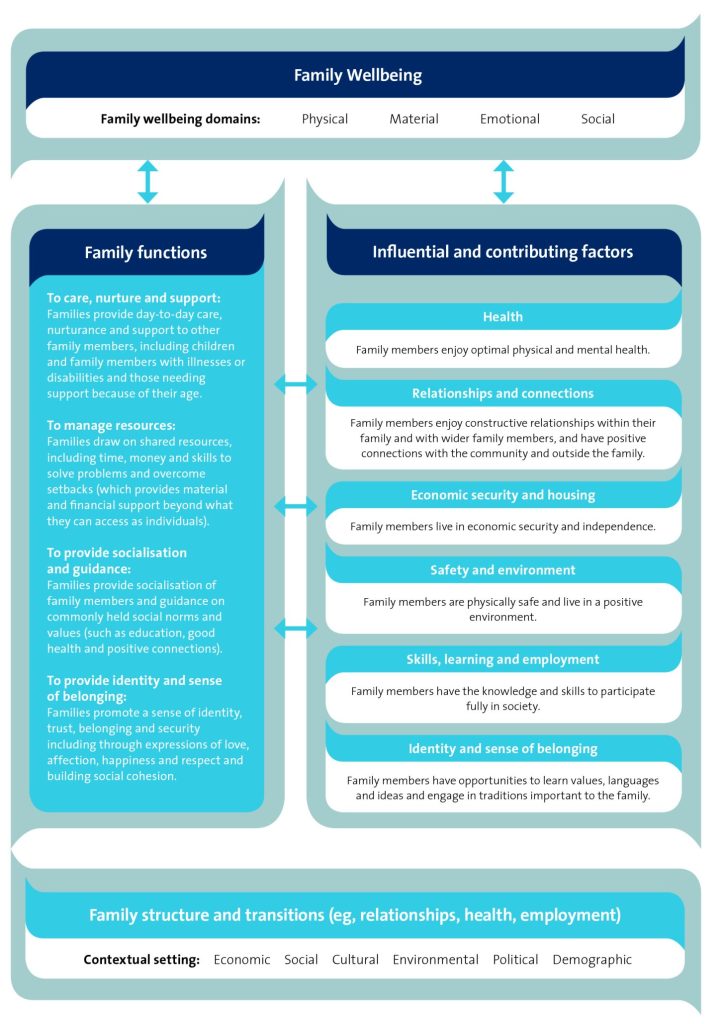

Family and whānau wellbeing frameworks reflect different worldviews

The frameworks show the different approaches to thinking about measures of wellbeing. The Family Wellbeing Framework is linear, with functions and factors as the key focus for wellbeing. By contrast, the Whānau Rangatiratanga Conceptual Framework is by nature circular – with whānau at the centre – and with whānau rangatiratanga principles informing all parts of the framework.

Unlike the family wellbeing stream, the whānau wellbeing stream was required to create the case for, and the space to, apply:

• Mātauranga Māori (Māori epistemology)

• Tikanga and kawa (Māori methodology)

• Kia Māori (lived expressions of being Māori/Māori ontology).

(Irwin et al., 2013, p 33)

Kaupapa Māori whānau researchers have learned from experience that not to do so results in ‘whānau’ wellbeing data being viewed from an Article III perspective – that is, Māori are seen solely as individual citizens required to ‘measure up’ to non-Māori norms.

Family Wellbeing Framework

This framework provides a comprehensive structure for understanding family wellbeing (see Figure 4.3). It identifies four core functions of family wellbeing, and factors that influence and contribute to the ability of families to fulfil their core functions. These core functions and factors contribute to family wellbeing across the wellbeing domains. There is a complex interplay across these functions, factors and domains.

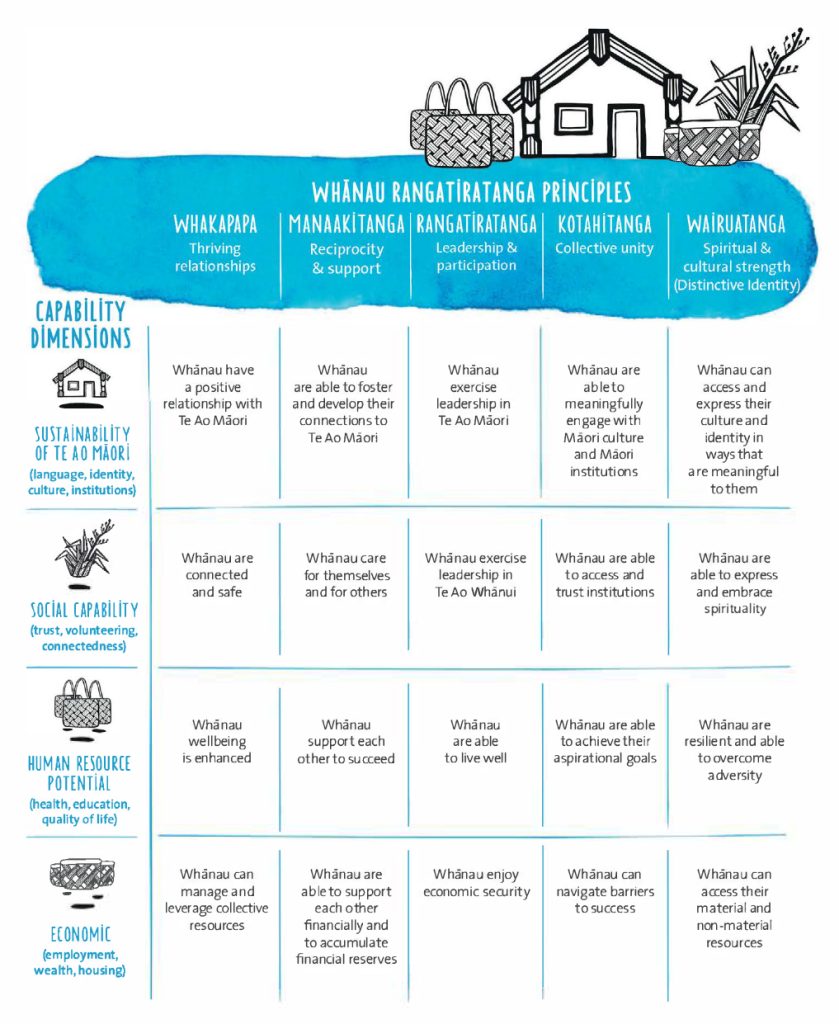

Whānau Rangatiratanga Conceptual and Measurement Frameworks

The Māori Statistics Framework shaped our approach to measuring whānau wellbeing. How this was arrived at is the subject of the report The Whānau Rangatiratanga Frameworks: Approaching whānau wellbeing from within Te Ao Māori (Superu, 2016). The Whānau Rangatiratanga Frameworks applied the capabilities identified in the Māori Statistics Framework and the te ao Māori principles identified from our Whānau Rangatiratanga work programme, to develop the Whānau Rangatiratanga Conceptual Framework and the Whānau Rangatiratanga Measurement Framework (see Figure 4.4).

The conceptual framework drew from capability dimensions of the Māori Statistics Framework, and whānau rangatiratanga principles, to measure and understand outcomes of whānau wellbeing. Inside the framework there are also capability dimensions that contribute to or influence whānau wellbeing (for example, whānau have a strong sense of belonging as Māori).

The whānau rangatiratanga principles and the capability dimensions of the Whānau Rangatiratanga Measurement Framework are portrayed as a dual-axis measurement framework (see Figure 4.5). The importance of this framework is that the whānau rangatiratanga principles provide the overall context for interpreting and understanding data on whānau wellbeing (Superu, 2015). As Kukutai et al. (2017, p 19) note:

There are specific indicators for each of these 20 outcomes (Superu 2015, chapter 4). For example the desired outcome for manaakitanga [ethic of care] within the ‘Social capability’ dimension is ‘Whānau care for themselves and others’. One of the indicators of this outcome in Te Kupenga is whether respondents have given some form of support to people living in other households.

Figure 4.3: Family Wellbeing Framework

From Superu, Families and Whanau Status Report 2015, p 36. Used under licence.

Figure 4.4: Whānau Rangatiratanga Conceptual Framework

Adapted from Superu, Families and Whanau Status Report 2015, p 38, under licence.

Figure 4.5: Whānau Rangatiratanga Measurement Framework

From Superu, Families and Whanau Status Report 2015, p 39. Used under licence.

Identification of family and whānau wellbeing research priorities

2013 Families and Whānau Status Report: The inaugural establishment report

This inaugural report for the Families and Whānau Wellbeing Research Programme provided the context and rationale for the two streams, exploring demographic trends and statistical profiles of families and of whānau, and introducing He Awa Whiria to frame the work:

The Commission has adopted the Braided River approach that supports the view that knowledge in New Zealand emanates from two separate streams, the Western Science stream and the Te Ao Māori (Māori world) stream. This approach has resulted in two distinct frameworks, one for thinking about family wellbeing and one for whānau wellbeing. This has allowed the different frameworks to come from, and sit within, their relevant cultural and values systems. (Families Commission, 2013, p 7)

The inaugural report presented significant contributions from experts in statistics and demographics for both Māori and New Zealand as a whole, and discussed definitions of family and whānau.

There is no universally agreed definition of what we mean by ‘family’

It was identified early on that definitions of family can vary by academic discipline and context – whether demographic, legal, policy or statistical. The existing statistical definition of family as a nuclear family did not accommodate the changing family patterns that were so evident in the demographic trends revealed in the 2013 report.

Understanding definitions of whānau underpins the Whānau Rangatiratanga frameworks

Drawing on Lawson-Te Aho’s work, we identified that whakapapa whānau are “the more permanent and culturally authentic form of whānau” (2010, p 24). We therefore determined that our whānau research programme would prioritise whakapapa whānau.

The problem that both streams had was that, while families and whānau are collective concepts, the only available ethnicity data was at an individual level. Furthermore, census ethnicity data is based on the occupier who filled out the form – neither children nor other ethnicities could be included. Initially, we needed to use ‘household type’ as a proxy.

Additionally, the 2013 report identified a number of challenges for developing statistical measures of whānau wellbeing, including:

• A lack of wellbeing and whānau data, especially in the Sustainability of Te Ao Māori domain – This left a number of relatively empty cells, as seen in the Whānau Rangatiratanga Measurement Framework.

• Existing conventional criteria to assess the potential indicators – The usual criteria of ‘consistent over time’ and ‘timeliness’ posed challenges to the measurement of whānau wellbeing.

• Limitations on Māori data in other datasets – In the report, Davies and Kilgour explored the feasibility of using other datasets, such as the Māori Language Survey, the Time Use Surveys and the General Social Survey. However, they found that as these surveys had not been routinely administered, nor comparable data collected on aspects of whānau wellbeing across surveys, the potential indicators would not meet the criteria for selection.

• Use of administrative data held by agencies – Once again, while administrative data (from, for example, the Ministry of Education) could provide insight into matters of interest for whānau wellbeing, the data was not available at a whānau level

(Davies and Kilgour, 2013, pp 132–42).

The inaugural report concluded that both work streams required a significant and multi-year research programme to address all the issues raised.

The first two annual reports (2013 and 2014) presented the rationale for the Families and Whānau Wellbeing Research Programme, demographic analyses and frameworks, and trialled the workability of the frameworks against the census, General Social Survey and some administrative data, to show changes over time.

Te Kupenga brings significant changes to the whānau research stream

The paucity of whānau data changed significantly with the introduction of Te Kupenga 2013 (the Māori Social Survey). Te Kupenga is a selfreported, nationally representative post-census survey of Māori wellbeing for those aged 15 years and over. It was developed by Statistics New Zealand following the 2013 census, with support from Te Puni Kōkiri and other key Māori stakeholders and communities. While individuals responded to the survey, the key point is that they were asked questions about the wellbeing of their whānau (Superu, 2015).

Our whānau wellbeing research programme mined this rich data source in all our reports from 2015 up to and including 2018. Now we could start identifying measurable indicators to populate the Whānau Rangatiratanga Measurement Framework fields, where, previously, significant gaps existed.

Summary of research priorities across the families and whānau wellbeing streams

Indicator selection shows the difference in the two streams

With the whānau stream, we needed indicators to reflect what whānau have identified as wellbeing. This did not occur until Te Kupenga was run in 2013.

Te Kupenga was an entirely fresh dataset, with opportunities for new and rich quantitative insights about whānau wellbeing. It enabled us to identify mostly new indicators of whānau wellbeing, and helped respond to data gaps (complemented by some existing census data). For example, Te Kupenga provided us with the following indicators in populating the Sustainability of Te Ao Māori section of the Whānau Rangatiratanga Measurement Framework:

• identification with tūrangawaewae (ancestral land)

• strong connection to tūrangawaewae

• visit to ancestral marae (Māori meeting house)

• unpaid work for hapū

• enrolment on iwi register

• a te reo Māori speaker in the whānau

• attendance at kōhanga reo, kura or wānanga (Māori language nests, Māori-medium schools and tertiary institutions). (Superu, 2016)

Prior to Te Kupenga, the only indicators available were ‘knowledge of iwi’, ‘participation in Māori medium education’ and ‘Māori language capacity’.

For the family stream, indicator selection was more about using existing sources – largely the General Social Survey, supplemented by the census, Household Economic Survey, Household Disability Survey and the Youth 2000 survey series.

In 2015, we continued He Awa Whiria, while presenting three new developments

Further to the frameworks and data previously presented in earlier reports, three new developments were:

• refinement and consolidation of the conceptual frameworks as the basis for measuring, monitoring and better understanding family and whānau wellbeing

• a coherent set of family wellbeing indicators

• a coherent set of whānau wellbeing indicators, using data from Te Kupenga. (Superu, 2015)

Now we could explore the following family and whānau types:

• couples without children living with them, further classified by whether or not the couple were both under 50 years of age

• families with at least one child under 18 years of age, further classified by whether one or two parents were living with them

• families where all the children were 18 years of age or older, further classified by whether one or two parents were living with them

Additionally, a further category emerged for the first time – that of the multi-whānau household.

In 2016, we explored family type and ethnicity, life course, and ‘expressions of whānau’

This research continued from previous family types, with the added nuance of ethnic differences within family wellbeing. The report analysed the wellbeing of European, Māori, Pacific and Asian families.

The analysis showed that younger European couples were faring reasonably well, while younger Māori and Pacific couples were more likely to volunteer and provide extended family support. However, they were also less likely to have post-secondary qualifications, impacting current and future incomes. Also, younger Asian couples were less well positioned economically, had high housing costs and felt less able to express their identities.

The research also confirmed earlier demographic trends indicating that single-parent families faced financial and psychological stresses across all four ethnic groups, while many had poorer health outcomes. Further, single-parent families with adult children had weaker connections to their extended families.

We introduced the life-course approach to better understand:

• the wide range of factors that influence family wellbeing

• what factors may impact on each person’s ability to fulfill their role in a family

• how families are carrying out their core functions (Superu, 2016).

At the same time, we further mined Te Kupenga to explore ‘expressions of whānau’ – who whānau members identified as their whānau. This research showed that the vast majority of Māori (99 per cent) think of their whānau in terms of genealogical relationships; however, the breadth of those relationships varies greatly (Kukutai et al., 2016).

The analysis challenged assumptions that those Māori families, who include non-kin in their definition of whānau, don’t have a strong sense of cultural identity. In fact, Kukutai et al. found that those who had participated in Māori medium education and/or lived in a home where te reo Māori was spoken were more likely to include in their definition of whānau those with whom they did not share whakapapa.

The analysis identified that a number of factors are related to whether or not individuals see their whānau as encompassing extended whānau, such as:

• demographic factors, specifically older age and place of residence

• a basic connection to one’s ancestral marae

• a high regard for being involved with Māori culture.

In 2017, we presented four new achievements

A measure of multiple disadvantage

In the families stream, the multiple-disadvantage research was a significant contribution to understanding how well New Zealand families are faring. A measure of multiple disadvantage was developed using indicators from the General Social Survey 2014 and input from a cross-sector reference group with representation from eight government agencies.

This measure includes sixteen indicators corresponding to eight life domains: education, health, income, housing, material wellbeing, employment, safety, and social connectedness. Superu has used this measure to explore the number and type of disadvantages experienced by New Zealand families. (Superu, 2017a, p 9)

While the number of disadvantages differed by family type, a significant minority (18 per cent) faced disadvantage in three or more of eight life domains (our definition of multiple disadvantage). For example, single parents with young children were much more likely to experience multiple disadvantages. Around half had three or more domains in disadvantage and just 12 per cent had none (Superu, 2017a).

The families stream also explored resilience amongst New Zealand families, and identified that strong, healthy relationships are at the heart of family resilience. Similarly, in the whānau stream it was the quality of whānau relationships that was considered the most significant driver of whānau wellbeing, despite economic impacts.

Te Ritorito 2017 – Towards whānau, hapū and iwi wellbeing

A key development in the whānau stream was a two-day national forum held between 3 and 4 April 2017, in partnership with Te Puni Kōkiri at Pipitea Marae, where many experts – in the development of whānau, hapū and iwi wellbeing research and measures – presented and shared their findings.

A goal of Te Ritorito 2017 was to highlight:

• whānau, hapū and iwi wellbeing research, policy and implementation

• what works with whānau, hapū and iwi

• future implications

• potential gaps in development, including the need for further engagement with whānau, hapū and iwi on these topics

(Superu, 2017b).

Subjective whānau wellbeing in Te Kupenga

From Te Kupenga, we identified that Māori who are part of a couple with at least one dependent child had the highest share reporting a high level of whānau wellbeing, and the lowest share reporting low wellbeing (25.3 per cent, 4.5 per cent respectively). By contrast, Māori who are part of a single-parent family had the lowest share reporting very high whānau wellbeing, and the highest share reporting a very low score (21.4 per cent, 8.2 per cent respectively) (Kukutai et al., 2017).

Bridging cultural perspectives

The 2017 Families and Whānau Status Report also presented a summary of Bridging Cultural Perspectives (the deliberations of the He Awa Whiria – Bridging Cultural Perspectives Steering Group), and explored questions such as when and how to braid, and whether the two streams ever become one (Arago-Kemp and Hong, 2018).

Key innovations in 2018

Families stream

A major achievement, in collaboration with the Ministry of Health and Statistics New Zealand, was to successfully add family-type classification to the individual records of the New Zealand Health Survey for the first time (Superu, 2015).

We also extended our multiple-disadvantage focus to examine whether there are differences in the rate and type of disadvantage faced by families across region and ethnic grouping, and how government expenditure maps to individuals with different levels of disadvantage.

Whānau stream

We continued our use of the whānau types previously identified to explore housing quality and health outcomes. Kukutai et al. (2017) found that Māori who headed single-parent households or who were part of multiple-whānau households were the most likely to report two or more housing problems of any magnitude, or at least one major problem.

The research identified that over two-thirds of Te Kupenga respondents (68 per cent) reported at least one housing problem (minor or major), with nearly half reporting two or more problems with housing quality (47 per cent) (Kukutai et al., 2018).

Can the Whānau Rangatiratanga Frameworks inform an evaluation of E Tū Whānau?

We assessed how the Whānau Rangatiratanga Frameworks could be used to evaluate the E Tū Whānau initiative (see Chapter 10 of this book). We wanted to understand the utility of the framework to inform evaluations of a broader suite of Ministry of Social Development kaupapa Māori programmes. In particular, it was evident that application of the Whānau Rangatiratanga Framework highlighted the underlying whānau capabilities that were required to achieve E Tū Whānau outcomes.

Some reflections on applying He Awa Whiria to a strategic research programme

The Families and Whānau Wellbeing Research Programme has endured, and underpinning this has been the development of robust dual frameworks for families and whānau. The frameworks guide our decision-making, analysis and interpretation of data as we grow the evidence base, while providing a deeper and more nuanced context to understanding drivers of both families and whānau wellbeing.

The two ‘streams’ produced two very distinct frameworks that led to different approaches, priorities and analyses. We found that our frameworks were vital to ensure our approach to growing data and evidence on families and whānau wellbeing was strategic and evidence-based.

He Awa Whiria provided the framing to support us to create the case for, and the space to, apply Māori epistemology, methodology and ontology to measures of whānau wellbeing (Irwin et al., 2013).

He Awa Whiria programmes require time to conceptualise and plan how best to approach both streams. In the early stages, we were able to identify the need for dual reference groups, frameworks and research priorities that could reflect family wellbeing and whānau wellbeing.

The lack of whānau wellbeing data reflected the fact that, historically, investment in te ao Māori research and development has not been equitable. The development of Te Kupenga 2013 went some way towards addressing the issues we articulated on the availability of whānau wellbeing indicators and measures. However, when planning a He Awa Whiria programme, it is important to realistically identify the resources required to effectively support the te ao Māori stream.

Kaupapa Māori expertise is central to a successful He Awa Whiria project. Fortunately, we were able to engage kaupapa Māori expertise for all our whānau wellbeing chapters. Our experts were supported by a strong Whānau Wellbeing Reference Group and, together, they were able to hold the space and simultaneously grow the evidence base, where previously there had been a dearth of whānau data. Considering the challenges, this in itself was a major achievement.

Braiding is iterative and cannot be forced. This is extremely important – it takes time for both streams to grow in their own capacity.

‘The sea’ remains just out of reach. While there are certainly times when the streams come together, in a strategic research programme, the ‘sea’ – like the far, distant horizon – forever recedes from us, drawing us forever onwards, towards new understandings about families and whānau wellbeing in New Zealand today.

![]()

Author’s note

I was employed at the Families Commission as a senior analyst and a Principal Advisor Māori from 2009 until 2017, pending its disestablishment in 2018. In that capacity, I worked on the Families and Whānau Wellbeing Research Programme and other kaupapa Māori research reports.

Over time, many researchers, expert advisors and staff have given significant levels of commitment to this programme to continue the creation of innovative family and whānau wellbeing research through a number of organisational restructurings and changes of government. I feel very privileged to have worked alongside you all, and I thank you for the learnings, experiences and relationships that have been very rich as a consequence.

When the Families Commission was disestablished, the Families and Whānau Wellbeing Research Programme, along with key staff, was transferred to the Research and Evaluation unit at the Ministry of Social Development, where I work as Principal Advisor Māori.

I am honoured to continue as kaitiaki (steward) for the significant kaupapa Māori contributions that have been made and that are ongoing within this innovative research programme.

Tihe mauri ora

![]()

References

Appendices to the Journals of the House of Representatives (1872), C4, Reports on Settlements of Confiscated Land.

Arago-Kemp, V. & Hong, B. (2018), Bridging Cultural Perspectives (Wellington: Families Commission).

Baker, K., Williams, H. & Tuuta, C. (2012), Te Pūmautanga o te Whānau: Tūhoe and South Auckland whānau (Wellington: Families Commission).

Cormack, D. (2010), The Practice and Politics of Counting: Ethnicity data in official statistics in Aotearoa/New Zealand (Wellington: Te Rōpū Rangahau Hauora a Eru Pōmare).

Couchman, J. & Baker, K. (2012), One Step at a Time: Supporting families and whānau in financial hardship (Wellington: Families Commission).

Davies, L. & Kilgour, J. (2013), ‘A framework towards measuring whānau rangatiratanga’, in Families and Whānau Status Report 2013. Towards measuring the wellbeing of families and whānau (131–42), (Wellington: Families Commission).

Families Commission, Whānau Strategic Framework: 2009–2012 (Wellington: Families Commission).

Families Commission (2013), Families and Whānau Status Report 2013. Towards measuring the wellbeing of families and whānau (Wellington: Families Commission).

Families Commission Amendment Act 2014 No. 9 (as at 30 June 2018), Public Act – New Zealand Legislation.

Hunn, J. (1961), The Hunn Report (Wellington: Department of Māori Affairs).

Irwin, K., Hetet, L., Maclean, S. & Potae, G. (2013), What Works with Māori: What the people said (Wellington: Families Commission).

Kukutai, T. & Cormack, D. (2022), Indigenous Peoples, Data, and the Coloniality of Surveillance: [PDF] https://researchcommons.waikato.ac.nz/bitstream/handle/10289/14911/Cormack-Kukutai2022_Chapter_IndigenousPeoplesDataAndTheCol.pdf?sequence=8

Kukutai, T., Roskruge, M. & Sporle, A. (2015), ‘Whānau wellbeing’, in Families and Whānau Status Report 2015 (95–123), (Wellington: Families Commission).

Kukutai, T., Roskruge, M. & Sporle, A. (2016), ‘Expressions of whānau’, in Families and Whānau Status Report 2016 (51–77), (Wellington: Families Commission).

Kukutai, T., Sporle, A. & Rata, A. (2018), ‘Housing quality, health and whānau wellbeing’, in Families and Whānau Status Report 2018 (75–148), (Wellington: Families Commission).

Kukutai, T., Sporle, A. & Roskruge, M. (2017), ‘Subjective whānau wellbeing in Te Kupenga’, in Families and Whanau Status Report 2017 (54–72), (Wellington: Families Commission).

Lawson-Te Aho, K. (2010), Definitions of Whānau: A review of selected literature (Wellington: Families Commission).

Macfarlane, A., Macfarlane, S. & Gillon, G. (2015), ‘Sharing the food baskets of knowledge: Creating space for a blending of streams’, in A. Macfarlane, S. Macfarlane & M. Webber (eds), Sociocultural Realities: Exploring new horizons (52–67), (Christchurch: Canterbury University Press).

Ministry of Social Development (2011), Conduct Problems: Effective programmes for 8–12 year olds, 2011 (Wellington: Ministry of Social Development).

Statistics New Zealand (2002), Towards a Māori Statistics Framework, Wellington.

Superu (2015), Families and Whānau Status Report 2015 (Wellington: Families Commission).

Superu (2016), The Whānau Rangatiratanga Frameworks: Approaching whānau wellbeing from within Te Ao Māori (Wellington: Families Commission).

Superu (2017a), Families and Whānau Status Report 2017 (Wellington: Families Commission).

Superu (2017b), ‘Te Ritorito 2017: Opportunities and challenges for whānau, hapū and iwi wellbeing’, in Families and Whanau Status Report 2017 (62–72), (Wellington: Families Commission).

Superu (2018), Families and Whānau Status Report 2018 (Wellington: Families Commission).

Superu and Te Puni Kōkiri (2017), Te Ritorito 2017: Towards whānau, hapū and iwi wellbeing: https://thehub.swa.govt.nz/resources/te-ritorito-2017-towards-whanau-hapu-and-iwi-wellbeing/

Wereta, W. & Bishop, D. (2004), ‘Towards a Māori Statistics Framework’, paper presented at the UN Meeting on Indigenous Peoples and Indicators of Well-being, 22–23 March 2006, Aboriginal Policy Research Conference, Ottawa, Canada.

- He Awa Whiria – Braided Rivers Advisory Group: Angus Macfarlane, Sonja Macfarlane, Graham Cameron, Richard Bedford, Maui Hudson, Richie Poulton and Peter Galvin ↵

- This group was specifically focused on the wellbeing research programme and therefore had a different focus to the Whānau Reference Group that was set up to give effect to key provisions in the Families Commission Act 2003. ↵