10 Infringement

Mitchell Adams

Contents

Infringement is a crucial concept in Australian designs law. It is also an important consideration for designers and whether they engage with the registration system. When Parliament introduced the Designs Act 2003 (Cth), it aimed to balance the rights of design owners with the broader public interest in innovation and competition. Dissatisfaction with the previous 1906 Act was due to the system doing ‘little to prevent free-riding, because of the low threshold and inadequate infringement test’.[1] The Hon Warren Entsch, in his second reading speech for the bill, stated that key features of the new system included ‘a higher threshold test for gaining rights and a broader infringement test, which will make a design registration harder to obtain but easier to enforce.’[2] For infringement to be established, a design needed to be an obvious or fraudulent imitation of a registered design – that is, virtually identical.[3] Under the new system, the infringement test was made consistent with the definition of distinctiveness. If another party makes a product that embodies a design that is identical or substantially similar in overall impression to a registered design, it constitutes an infringement. Now, twenty years into the new Act, dissatisfaction is not the focus of discussion; rather, it is the inability to efficiently and effectively enforce rights in designs.

In 2020, IP Australia surveyed Australian design-focused businesses to examine the methods and motives for protecting designs, experiences of copying, and barriers to the enforcement of rights.[4] Of the respondents, 47% indicated they do not seek formal or informal protection for their designs, with many expressing a lack of knowledge about the registration system.[5] Those who sought formal protection indicated the following:

- A registered design is an important form of protection.[6]

- Registration was sought to prevent others from copying their design or obtaining rights over related designs.[7]

- 27% believed that a third party had copied their design.[8]

Of those who believed someone was copying, 23% of individuals and 34% of industry respondents took no action to enforce their rights. One reason these design owners did not enforce their rights was that they believed the costs of enforcement were too high.[9] One respondent stated, “Much of the frustration of the current system is that extent of protection for small creative industries is beyond the financial means of small independent designers, and the cost of pursuing anyone, even if protected, is prohibitive.”[10] The other reasons included:[11]

- Felt the copying party was too big

- Believed copying would be hard to prove

- Uncertainty as to the validity of the pre-existing rights

Copying itself is not always considered negative.[12] For example, copying can be important in the fashion industry’s swift innovation cycle,[13] or in software development, where copyright feeds word of mouth and increases sales of original products.[14]

Understanding design infringement is crucial for several reasons. For design owners, it provides a framework to protect their intellectual property rights and maintain their competitive advantage in the marketplace. For competitors and other industry participants, it establishes clear boundaries around what constitutes acceptable behaviour.

This chapter explores the nature of design infringement. It begins by examining the exclusive rights granted to design owners and how these rights can be infringed. The chapter then delves into the various types of infringement recognised by the Act, including both primary and secondary. Although an identical design in the marketplace to a registered design is easy to spot, most infringement cases revolve around when an alleged design is too similar to a registered one. Therefore, particular attention is paid to the comparison of substantial similarity in overall impression, which forms the cornerstone of many infringement analyses. Throughout this chapter, reference will be made to significant cases that have shaped our understanding of design infringement. These cases provide practical examples of courts interpreting and applying the Designs Act 2003 (Cth) provisions.

The chapter also examines the defences against infringement claims, including the important spare parts exception and the repairs defence. These defences reflect Parliament’s recognition that absolute design rights could stifle competition and innovation in certain circumstances. The chapter then explores the practical aspects of infringement proceedings, including the available remedies and the possibility of counter-claims for revocation.

Rights Conferred by a Registered Design

Saying that an owner of an intellectual property right has a monopoly over their creation exaggerates intellectual property protection.[15] The Act grants specific exclusive rights to the design owner. For example, the registered owner has the exclusive right to reproduce the design, being the only one allowed to make a product that embodies the registered design.[16] Therefore, exclusivity is defined by what is registered with IP Australia and the rights under the Act. If a third party engages in exclusive acts related to the registered design, they infringe on the conferred rights. Such exclusivity may attract applicants to register their design.[17]

The exclusive rights granted to a registered design are set out in section 10 of the Act. These rights conferred to the owner of a registered design, define the scope of protection for design owners and establish the basis for infringement discussed in this chapter. Read the section below. Importantly, as discussed in Chapter 3, the design must first be examined and certified to enforce these rights.

Read

DESIGNS ACT 2003 – SECT 10

Exclusive rights of registered owners

(1) The registered owner of a registered design has the exclusive right, during the term of registration of the design:

(a) to make or offer to make a product, in relation to which the design is registered, which embodies the design; and

(b) to import such a product into Australia for sale, or for use for the purposes of any trade or business; and

(c) to sell, hire or otherwise dispose of, or offer to sell, hire or otherwise dispose of, such a product; and

(d) to use such a product in any way for the purposes of any trade or business; and

(e) to keep such a product for the purpose of doing any of the things mentioned in paragraph (c) or (d); and

(f) to authorise another person to do any of the things mentioned in paragraph (a), (b), (c), (d) or (e).

(2) The exclusive rights mentioned in subsection (1) are personal property and are capable of assignment and of devolution by will or by operation of law.

(3) This section is subject to this Act.

The rights granted by registration are exclusively economic in nature, focusing on the commercial exploitation of the design. Unlike copyright law, which recognises moral rights,[18] design rights specifically target commercial activities involving products that embody the registered design. This commercial focus reflects the industrial nature of design protection and its role in promoting innovation in product design.[19]

Territorial limitations

A design registered in Australia provides protection only within Australian territory.[20]. However, this territorial limitation can create challenges in an increasingly globalised marketplace, where products are often manufactured in one jurisdiction and sold in another. Some of the exclusive rights offered under Section 10 include importing a product that embodies a registered design.[21]

Duration of Rights

As introduced in Chapter 3, the Act prescribes the duration of design rights for a maximum of 10 years. Initial registration provides five years of protection, with the possibility of a single renewal for an additional five years.[22] The 2003 Act shortened the maximum duration for registered designs from 16 to 10 years.[23]

The length of protection aligns with the minimum set by the TRIPS Agreement, but it falls short compared to other jurisdictions. While the protection term is short compared to other intellectual property rights, this may also reflect the commercial reality of product design lifecycles and the need to balance monopoly rights with market competition. The ten-year term contradicts the ALRC’s recommendation of a maximum protection period of 15 years. The term choice is explained in the Explanatory Memorandum as, ‘…it would not be in Australia’s interest to provide a period of registration in excess of its international obligations as Australia is a net importer of intellectual property’.[24] During ACIP’s review of the registered design system, submissions indicated that the term was too short, with a majority of respondents preferring a 15-year term.[25] However, a recommendation for a term change did not appear in ACIP’s final report. Interestingly, ACIP found that less than 20 per cent of registered design rights were renewed after an initial term of 5 years.[26] This finding indicated that any extension of the term beyond 10 years would be valuable to only a small number of owners.[27]

Infringement

The Act states that a person infringes a registered design if, without the appropriate authority, they deal with a product that embodies the design or a substantially similar design in certain ways. This provision largely reflects the exclusive rights to which a registered owner is entitled under section 10, with one notable exception. Additionally, the registered design must be examined and certified before a registered owner can commence infringement proceedings.[28] Read the section below that sets out the types of infringement.

Read

DESIGNS ACT 2003 – SECT 71

Infringement of design

(1) A person infringes a registered design if, during the term of registration of the design, and without the licence or authority of the registered owner of the design or an exclusive licensee, the person:

(a) makes or offers to make a product, in relation to which the design is registered, which embodies a design that is identical to, or substantially similar in overall impression to, the registered design; or

(b) imports such a product into Australia for sale, or for use for the purposes of any trade or business; or

(c) sells, hires or otherwise disposes of, or offers to sell, hire or otherwise dispose of, such a product; or

(d) uses such a product in any way for the purposes of any trade or business; or

(e) keeps such a product for the purpose of doing any of the things mentioned in paragraph (c) or (d).

(2) Despite subsection (1), a person does not infringe a registered design if:

(a) the person imports a product, in relation to which the design is registered, which embodies a design that is identical to, or substantially similar in overall impression to, the registered design; and

(b) the product embodies the design with the licence or authority of the registered owner of the design or an exclusive licensee.

(3) In determining whether an allegedly infringing design is substantially similar in overall impression to the registered design, a court is to consider the factors specified in section 19.

(4) Infringement proceedings must be started within 6 years from the day on which the alleged infringement occurred.

For an infringement to occur, there must be:

- A doing of one or more of the infringing acts in s 71(1)

- The acts are done without the licence or authority of the registered owner

- It must occur during the term of registration of the design[29]

- It is in relation to a product for which the design is registered

- The product either embodies the design (i.e., identical) or is substantially similar

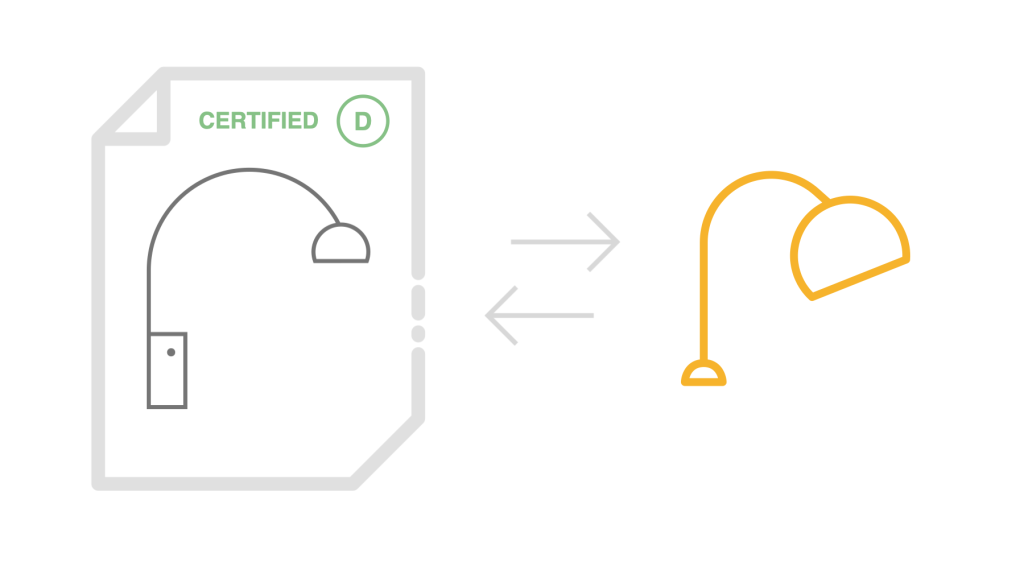

To understand the provision and types of infringements, the alleged infringing activity must involve a product for which the design is registered. If a design is registered in relation to a toy, creating a lamp in the same shape or configuration would not be considered an infringement. Therefore, the design and product registered with IP Australia are important. Moreover, ‘infringement is determined by comparing the allegedly infringing product against the registered design, not by comparing a product embodying the registered design against the infringing product.’[30]

The 2003 Act was drafted so that the test for infringement is the same as for registration. Specifically, the allegedly infringing product must be identical or substantially similar in overall impression to the registered design.[31] As the ALRC stated during its review, ‘The infringement and distinctiveness tests should be the same so that an infringing design is not a distinctive design and vice versa’.[32] The intention was to broaden the scope of protection.[33] Therefore, the considerations discussed in Chapter 5 are relevant here. Furthermore, the factors under section 19 that help determine a design’s distinctiveness must be considered to determine whether a design infringes another and must be considered by a court.[34] The approach ensures that infringement is assessed in the context of the overall appearance of the competing designs (while considering the standard of the familiar user) rather than focusing on the differences between the two designs.[35]

Emmett J described the analysis of substantially similar in overall impression in the context of infringement in Keller v LED Technologies:[36]

Questions of infringement and novelty or originality are connected. One may be able to take into account the state of knowledge at the time of registration, and in what respects the design was new or original, when considering whether any variations from the registered design that appear in the alleged infringement are substantial or immaterial. Where novelty or originality is discovered in slight variations, there cannot be infringement without a very close resemblance between the registered design and the article alleged to be an infringement of the design. The Court should have regard to what was known at the priority date and if the particular features that provide a novel conception have not been reproduced in the alleged infringement, the similarity of appearance between the article complained of and the registered design, if present, must necessarily reside in the common possession of characteristics that are free to everybody to employ. Small differences between the registered design and the prior art will generally lead to a finding of no infringement, if there are equally small differences between the registered design and the alleged infringing article. On the other hand, the greater the advance in the registered design over the prior art, the more likely that the Court will find common features between the design and the alleged infringing article to support a finding of infringement…

Importantly for designers and those who file applications, what you file (including the representations) informs the scope of the design. As discussed in Chapter 3, a product’s visual features influence the product’s overall appearance and, in turn, the scope of the design. Certain features can, therefore, be emphasised in an application’s representations. These elements can help navigate the comparison. It must be kept in mind, however, that the comparison is substantially similar in overall impression. The concept requires consideration of the product as a whole, not just the part of the product where the particular visual features of the design are located.

For example, the inclusion or exclusion of colour from the application registrations could affect the infringement analysis. In Review 2 Pty Ltd v Redberry Enterprise Pty Ltd,[37], the Federal Court considered differences in colour as part of the substantial similarity assessment in the context of fashion garments. Keen J stated:[38]

The fact that a design is registered in colour through the use of colour photographs (unaccompanied by a statement of newness and distinctiveness) is relevant to determining the extent of the monopoly sought and given. Everything that is shown in the registered design (unless disclaimed in some way) forms part of the subject matter protected by registration. The pattern (including colour) that is shown on the registered Review Design is thus part of what is protected, and is, as the above reasoning indicates, to be accorded some weight. How much weight is to be given to pattern and colour will depend on the nature of the product and the relative importance of the different visual features of the registered design, as viewed by the informed user, having regard to the prior art, and the freedom of the designer to innovate. If colour is important, it will be so because the factors relevant to the registered design lead to this conclusion. As indicated already, pattern, including colour, is a feature that an informed user would consider has some significance in creating the overall impression of the Review Design, a conclusion borne out by the use of colour photographs to depict the design in the registration application.

In the present case, an informed user would, as Ms Mudie’s evidence and the prior art showed, regard colour as an element in the pattern that forms part of the overall look of the registered Review Design. The Review Design is depicted on the register in a colour photograph of a store dummy wearing a garment in a patterned fabric in natural tones with orange, brown and blue fine ‘fronds leaf’ pattern, giving it, as Ms Mudie and Ms Ellis agreed, an African or tropical look. This pattern (and the colour that is part of it) is, however, only one element in the overall impression of the registered design. It is, as previously observed, entirely different from the pattern on the Redberry garment.

Types of Infringement

The Act recognises two categories of infringement, primary and secondary.[39] This dual approach reflects the complex nature of modern commercial activities and the various ways in which design rights can be infringed. To determine the specific kinds of infringement a third party has engaged in, it is helpful to consider the commercial development, production, distribution, and sale of a product. Different exclusive rights can be infringed at various stages of the product.

Primary infringement

Primary infringements are those mentioned in paragraph 71(1)(a) of the Act.[40] This kind of infringement occurs through direct engagement with the registered design without proper authorisation. Although the Act does not define the word ‘make’, it refers to creating, constructing, or causing something to exist.[41] The concept here centres on the commercial exploitation of products that embody designs identical to or substantially similar in overall impression to the registered design. In addition, there is no knowledge requirement, and a primary infringement can be committed innocently or in ignorance of the registered design.[42]

The scope of the provision has been discussed by the courts, where alleged infringers have sought to distinguish between a product made by employees and one made by independent contractors. Jessup J, in Review Australia Pty Ltd v Innovative Lifestyle Investments Pty Ltd, held that a person who ‘directs, causes or procures the product to be made by another’ is considered to make a product within the scope of s 71(1)(a).[43]

In the policy context of the Designs Act, I consider that the reference, in s 71(1)(a) thereof, to a person who “makes” a product includes a reference to a person who directs, causes or procures the product to be made by another, whether or not an employee of the person. To accept, as the respondents did, the application of the provision to a situation in which the product is made by an employee of the person necessarily excludes the construction that the word “makes” refers only to the manual task of making by the person himself or herself. That being so, there is no intelligible point, consistent with the scope and purpose of Part 2 of Ch 6 of the Designs Act itself, at which a line should be drawn so as to exclude the making of a product by a contractor to, but at the direction of, the person.

Understanding who directed the product’s creation is important. Someone in Australia could direct or procure a product to be made by another, but the actual manufacturing or creation might occur overseas. This situation is plausible as many low-cost manufacturing options are offshore (for example, in China). From the perspective of the registered design owner, is the act of direction or procurement an infringement under the provision, or must the manufacturing of the product occur in Australia?

As discussed above, there is a territorial limit to the application of the Act. Therefore, there is an implied territorial limit to section 71(1)(a)—the product needs to be made in Australia to fall under the provision.[44] Gordon J in LED Technologies Pty Ltd v Elecspess Pty Ltd,[45] took the view that an Australian-based procurer would not be engaging in primary infringement. To hold otherwise, her Honour said:[46]

… would risk improperly subjecting unwitting foreign companies (assuming a plaintiff could satisfy personal jurisdiction, service of process and other procedural requirements) to liability in Australia for acts which might be perfectly legal in terms of their own domestic intellectual property regimes. It would be tantamount to holding that a company which does business wholly within foreign borders ought to be charged, when doing business with an Australian client, with knowledge of Australian design law as well as a duty under that law to verify the provenance of designs provided to it for manufacture.

However, considering the practical realities of this situation, any eventual importation of the infringing product with the design could constitute a secondary infringement.[47] ‘Offers to make’ would involve providing the services to create or manufacture the product. Similarly, there is a territorial limit here, and the manufacturer would need to be within Australia.

Secondary infringement

Secondary infringements are the remaining infringing acts found in s 71(1).[48] These capture other activities relevant to the distribution and sale of a product. The inclusion of secondary infringement reflects Parliament’s recognition that design infringement often involves multiple parties and various stages. For example, the case of GM Global Technology Operations LLC v S.S.S. Auto Parts Pty Ltd involved an alleged infringement of registered designs of automotive spare parts imported and sold in Australia.[49] The case is described in more detail below.

However, the remaining acts must be done for a commercial purpose. For example, importing a design into Australia for private domestic use would not be considered a secondary infringement.

Authorisation

A notable inconsistency in the Act occurs between section 10, which details the exclusive rights of design owners, and section 71, which defines the limitations of infringement. Specifically, paragraph 10(1)(f) indicates that the owner of a registered design possesses the right ‘to authorise another person to perform any of’ the acts included within the exclusive rights. This would involve permitting a third party to manufacture or sell a product that utilises the design. In contrast, section 71 lacks a corresponding provision. This discrepancy introduces confusion about the extent of secondary liability for infringement when it is present in other areas of intellectual property law like copyright.[50] The ARLC’s 1996 report made no recommendation against authorisation liability. In addition, the Explanatory Memorandum for the Act contained no explanation or justification for its absence.[51] Although it can be argued that the lack of a corresponding infringing act in s 71 was not an omission of the Government and did not intend for it to be an infringing act.[52] ACIP, in their report, commented on the omission and recommended leaving s 71 as is:[53]

The obvious ‘fix’ is to amend section 71 so that it matches section 10. This would have the benefit of removing an obvious (and apparently unintended) anomaly in the Act. It would also give courts some flexibility to extend and adapt secondary liability in the area of designs over time. ‘Authorisation’ in the field of IP has developed into a broad form of liability which allows a third party to be held liable in circumstances where they have knowledge of primary infringement, the power to prevent the infringement and fail to take reasonable steps to avoid or reduce the infringement. This broad understanding of authorisation as ‘sanctioning, countenancing or approving’ infringement has developed in copyright but has also been applied in the area of patents (explicitly adopting the reasoning from the copyright cases). Authorisation in copyright has itself been the subject of significant controversy in recent years. Thus ‘fixing’ this anomaly would create some uncertainty and could have unintended effects, particularly in the area of 3D printing where it might be argued that some entities involved in 3D printing or the circulation of designs may ‘sanction, countenance or approve’ infringement.

As an alternative to authorisation, courts have recognised that a third party may be deemed liable as a joint tortfeasor.[54] Registered owners could turn to the common law action of joint tortfeasorship. Liability for joint tortfeasors has been used in design infringement actions to impose personal liability on directors of companies.[55] For parties to be considered joint tortfeasors “there must be a concurrence in the act or acts causing damage, not merely a coincidence of separate acts which by their conjoined effect, caused damage.”[56] Moreover, joint tortfeasors need to have acted in concert to achieve a common end. Some level of connection between the parties is required beyond mere facilitation of the infringement.[57]

In Keller v LED Technologies Pty Ltd,[58] the Full Federal Court addressed whether two directors should be personally liable as joint tortfeasors for their companies’ design infringement. The Court established that while companies can only act through natural persons, this does not automatically make directors liable for the infringement.[59] Directors must do something beyond merely acting as directors – they must personally be ‘an invade of the victim’s rights’.[60] Besanko J said that:.[61]

…A “close personal involvement” in the infringing acts by the director must be shown before he or she will be held liable. The director’s knowledge will be relevant. In theory, that knowledge may range from knowledge that the relevant acts are infringing acts to the knowledge of an applicant’s registered designs to the knowledge of acts carried out by others.

The Court applied these principles differently to the two directors involved. For Armstrong, who served primarily as chairman, the Court found no basis for personal liability. Although Armstrong was aware of the registered designs, he was not involved in the day-to-day operations, and there was no evidence that he knew or believed the company’s sales would constitute infringement. The Court rejected the trial judge’s finding that Armstrong showed “conscious indifference” to the risk of infringement, noting this was never put to him in cross-examination.[62]

Keller’s case was more complex due to his deeper involvement in designing the products and arranging their manufacture and importation. However, the Court ultimately found that these activities did not justify personal liability. The critical factor was that Keller performed these actions on behalf of the companies rather than in a personal capacity.[63] He was not using the companies as instruments for his own conduct, and his actions demonstrated no dimension separate from the good faith discharge of his duties as a director.[64] This shows that even substantial involvement in potentially infringing activities will not trigger personal liability if the director genuinely acts in the company’s interests rather than their own.

The decision indicates that courts will only find directors personally liable if they step outside their proper roles as directors and consciously seek infringement for their own purposes instead of the company’s interests.

Analysing substantial similarity in overall impression

The assessment of substantial similarity in overall impression is likely the most crucial element in determining infringement, especially since identical designs are easier to identify. This assessment must be undertaken from the perspective of the familiar person,[65] a hypothetical person familiar with the product and its design environment (see more information on the standard of the familiar person in Chapter 5). The analysis requires consideration of the factors discussed in Chapter 5, including the state of development of the prior art base,[66] any statement of newness and distinctiveness,[67] and the freedom available to create designs in the relevant field.[68]

Courts have grappled with these concepts in several cases. In Review 2 Pty Ltd v Redberry Enterprise Pty Ltd, the Federal Court provided valuable guidance on assessing substantial similarity, emphasising the importance of considering the overall impression rather than focusing on individual details.[69] This approach recognises that design protection extends beyond exact copying to encompass designs that create the same overall visual impression. In GME Pty Ltd v Uniden Australia Pty Ltd. Burley J noted that, while design infringement is a matter of impression:[70]

It is necessary to focus on the overall impression created by the two designs. This is done not by ignoring matters of detail, but by assessing the impact of particular visual features, including any matters of detail, on the overall impression created by each of the two designs.

At this point, it may be valuable to revisit Chapter 5 to consider the assessment and the factors under s 19.

Notable design infringement cases

Reported design infringement cases help navigate substantial similarity assessments and involve interesting designs. Some notable design infringement cases after the introduction of the 2003 Act include those involving vehicle lights, women’s dresses, ceiling fans, and radio microphone equipment. Many design decisions not only involve questions of infringement but also whether the registered design is distinctive or even invalid.

Read

In Keller v LED Technologies Pty Ltd, the Full Federal Court considered an appeal involving the alleged infringement of registered designs for vehicle taillights.[71] The Court addressed several issues, including whether the designs were invalid due to unclear representations, whether they lacked distinctiveness compared to the prior art base, and whether the respondent’s products infringed the registered designs. The Court provides valuable guidance on assessing the clarity of design representations, the role of statements of newness and distinctiveness, and evaluating substantial similarity in overall impression when considering both validity and infringement.

Read the full judgment here and consider how the court weighed up the similarities versus differences when comparing the designs: Keller v LED Technologies Pty Ltd [2010] FCAFC 55

Read

In Review 2 Pty Ltd v Redberry Enterprise Pty Ltd [2008] FCA 1588, the Federal Court heard a dispute between two fashion retailers over allegedly similar dress designs. The case provides critical guidance on how courts assess substantial similarity in overall impression under the Act, particularly from the perspective of the ‘informed user’ (now the familiar person). Justice Kenny explored who qualifies as an informed user/familar person in the fashion industry context and how visual features like pattern, colour and skirt shape contribute to the overall impression of a design. The decision offers valuable insight into how courts balance similarities and differences between designs while considering factors such as the state of development of the prior art base and the freedom of designers to innovate. This case remains a leading authority on design infringement analysis and the application of the standard.

Read the full judgment here: Review 2 Pty Ltd v Redberry Enterprise Pty Ltd [2008] FCA 1588

Read

Hunter Pacific International Pty Ltd v Martec Pty Ltd [2016] FCA 796 examines design infringement in the context of ceiling fans. The case provides important guidance on how courts should conduct the visual comparison required by the Act to determine substantial similarity in overall impression. Justice Nicholas emphasises that while the comparison must be careful and deliberate rather than casual, mathematical measurements and precise ratios play no role— it is the overall visual impression that matters. The decision is particularly instructive in how courts should weigh the relative importance of different visual features. His Honour found that features more visible from typical viewing angles (like the lower hub when installed on a ceiling) deserve greater consideration. The case remains significant for its practical approach to applying the standard when comparing designs.

Read the full judgment here: Hunter Pacific International Pty Ltd v Martec Pty Ltd [2016] FCA 796

Read

GME Pty Ltd v Uniden Australia Pty Ltd is a Federal Court decision demonstrating how courts assess substantial similarity in design infringement cases, particularly for products with functional constraints.[72] The case concerned whether Uniden’s XTRAK microphone infringed GME’s registered design for a handheld radio microphone. Justice Burley provides detailed guidance on conducting the visual comparison required by s 19, emphasising that while functional requirements (like the location of technical buttons) may limit design freedom, they do not completely ‘drive the design’.[73] The decision is particularly valuable for its analysis of how to weigh similarities against differences while considering both the overall impression and the prior art base and for showing how courts should assess the significance of individual design features within the context of the whole design.

Read the full judgment here: GME Pty Ltd v Uniden Australia Pty Ltd [2022] FCA 520

Applying infringement principles in practice

Remember, when analysing whether an infringement has occurred, consider:

- Has the third party engaged in one or more infringing acts in s 71(1)?

- Were these acts done without licence or authority?

- Did it occur during the term of registration?

- Is the alleged infringing product the same as the registered design?

- Does the product embody an identical design?

- Does the product embody a design that is substantially similar in overall impression?

When considering the last question, follow the steps to assess infringement:

- Identify the visual features of both designs

- Compare the designs, giving more weight to similarities

- Consider the state of development of the prior art

- Apply the perspective of the familiar

- Take into account the designer’s freedom to innovate

Defences to Design Infringement

The Designs Act 2003 (Cth) provides defences to allegations of design infringement. These defences reflect Parliament’s recognition that absolute design rights could potentially stifle innovation and competition in certain circumstances. The defences balance design owners’ interests with broader public interests in competition, innovation, and practical necessity.

Prior Use Defence

The Designs Amendment (Advisory Council on Intellectual Property Responses) Act 2021 (Cth) introduced an exemption to infringement for prior use of a design. The provision was added due to the introduction of the 12-month grace period. Section 71A protects those who were using a design or had taken definite steps to use a design before the priority date of the registered design. This defence acknowledges that independent creation and use should not be penalised simply because another party later registered the design. The defence is particularly important in industries where different parties might independently develop similar design solutions. The provision has yet to be raised in litigation.

Read

DESIGNS ACT 2003 – SECT 71A

Infringement exemption–prior use

(1) In relation to a registered design where the priority date of the design is on or after the commencement of this section, a person may, without infringing the registered design, do an act:

(a) that is referred to in paragraph 71(1)(a), (b), (c), (d) or (e); and

(b) that would infringe that registered design apart from this subsection;

if before that priority date:

(c) the person had:

(i) made a product, in relation to which the design became registered, which embodied a design (the comparable design ) that was identical to, or substantially similar in overall impression to, the design that became registered; or

(ii) imported such a product into Australia for sale, or for use for the purposes of any trade or business; or

(iii) sold, hired or otherwise disposed of such a product; or

(iv) used such a product in any way for the purposes of any trade or business; or

(v) kept such a product for the purpose of doing any of the things mentioned in subparagraph (iii) or (iv); or

(d) the person had taken definite steps (contractually or otherwise and whether or not in Australia) to do an act covered by paragraph (c).

(2) Subsection (1) does not apply unless immediately before the priority date of the registered design:

(a) either:

(i) the person was doing an act covered by paragraph (1)(c); or

(ii) the person was not doing such an act only because the person had temporarily stopped the doing of such an act; or

(b) either:

(i) the person was taking the steps covered by paragraph (1)(d); or

(ii) the person was not taking such steps only because the person had temporarily stopped the taking of such steps.

Limit if comparable design derived from registered owner etc.

(3) Subsection (1) does not apply if the person derived the comparable design from one of the following entities:

(a) the person who became the registered owner of the registered design referred to in subsection (1);

(b) any predecessor in title of the person referred to in paragraph (a);

(c) the person who created that registered design if that person is not covered by paragraph (a) or (b);

unless the derivation was from information made publicly available by or with the consent of an entity covered by paragraph (a) or (b).

Exemption for successors in title

(4) A person (the disposer ) may dispose to another person the whole of the disposer’s entitlement under subsection (1) or this subsection to do an act without infringing the registered design referred to in subsection (1). If there is such a disposal, the other person may, without infringing that registered design, do an act:

(a) that is referred to in paragraph 71(1)(a), (b), (c), (d) or (e); and

(b) that would infringe that registered design apart from this subsection.

Exemption for persons who obtain products

(5) If a person sells or otherwise disposes of a particular product to another person:

(a) in accordance with subsection (1) or (4) or this subsection; and

(b) without infringing the registered design referred to in subsection (1);

the other person may, without infringing that registered design, do an act:

(c) that is referred to in paragraph 71(1)(c), (d) or (e) in relation to that product; and

(d) that would infringe that registered design apart from this subsection.

Repairs Defence

One of the most significant provisions in the Act is the repairs defence under section 72. This defence allows the use of a registered design to repair a complex product and restore its overall appearance. The provision acknowledges the practical necessity of allowing complex product repairs and maintenance without infringing design rights. However, the scope of this defence has drawn judicial attention, especially in defining what qualifies as a ‘repair’ versus a modification or enhancement.

Read

DESIGNS ACT 2003 – SECT 72

Infringement exemption–repairs

(1) Despite subsection 71(1), a person does not infringe a registered design if:

(a) the person uses, or authorises another person to use, a product:

(i) in relation to which the design is registered; and

(ii) which embodies a design that is identical to, or substantially similar in overall impression to, the registered design; and

(b) the product is a component part of a complex product; and

(c) the use or authorisation is for the purpose of the repair of the complex product so as to restore its overall appearance in whole or part.

(2) If:

(a) a person (the first person) uses or authorises another person to use a product:

(i) in relation to which a design is registered; and

(ii) which embodies a design that is identical to, or substantially similar in overall impression to, the registered design; and

(b) the first person asserts in infringement proceedings that, because of the operation of subsection (1), the use or authorisation did not infringe the registered design;

the person bringing the infringement proceedings bears the burden of proving that the first person knew, or ought reasonably to have known, that the use or authorisation was not for the purpose mentioned in paragraph (1)(c).

(3) For the purposes of subsection (1):

(a) a repair is taken to be so as to restore the overall appearance of a complex product in whole if the overall appearance of the complex product immediately after the repair is not materially different from its original overall appearance; and

(b) a repair is taken to be so as to restore the overall appearance of a complex product in part if any material difference between:

(i) the original overall appearance of the complex product; and

(ii) the overall appearance of the complex product immediately after the repair;

is solely attributable to the fact that only part of the complex product has been repaired.

(4) In applying subsection (3), a court must apply the standard of a person who is familiar with the complex product, or products similar to the complex product (whether or not the person is a user of the complex product or of products similar to the complex product).

(5) In this section:

“repair”, in relation to a complex product, includes the following:

(a) restoring a decayed or damaged component part of the complex product to a good or sound condition;

(b) replacing a decayed or damaged component part of the complex product with a component part in good or sound condition;

(c) necessarily replacing incidental items when restoring or replacing a decayed or damaged component part of the complex product;

(d) carrying out maintenance on the complex product.

“use”, in relation to a product, means:

(a) to make or offer to make the product; or

(b) to import the product into Australia for sale, or for use for the purposes of any trade or business; or

(c) to sell, hire or otherwise dispose of, or offer to sell, hire or otherwise dispose of, the product; or

(d) to use the product in any other way for the purposes of any trade or business; or

(e) to keep the product for the purpose of doing any of the things mentioned in paragraph (c) or (d).

For the defence to apply, the product in relation to which the design is registered must be a ‘component part of a complex product’ (see Chapter 4). The use, which is defined in s 72(5) must be for the ‘purposes of the repair of the complex product so as to restore its overall appearance in whole or part’.

A repair is taken to mean the repair of a complex product so as to restore its overall appearance, whether it is whole or part. It can also include:

(a) restoring a decayed or damaged component part of the complex product to a good or sound condition;

(b) replacing a decayed or damaged component part of the complex product with a component part in good or sound condition;

(c) necessarily replacing incidental items when restoring or replacing a decayed or damaged component part of the complex product;

(d) carrying out maintenance on the complex product.

Under the provision, the registered owner has the burden of proving that the defendant knew, or ought reasonably to have known, that the use or authorisation was not for the purpose of repair.[74]

The Federal Court grappled with the provisions in GM Global Technology Operations LLC v S.S.S. Auto Parts Pty Ltd in the context of automotive spare parts, providing valuable guidance on interpreting this exception.[75] The Court’s analysis emphasised the need to consider both the purpose of the component part and its relationship to the complex product as a whole while commenting on the high burden placed on the plaintiff. General Motors brought the claim regarding designs for spare parts for Holden cars. They had the burden to show that the spare parts were not used to repair the overall appearance of the cars. Their claim was that the importation of the parts was used to enhance the cars or ‘up-spec’ their appearance.

A summary of the facts of the case includes:

- GM Holden Ltd (Holden) sold Holden Commodore vehicles in Australia. At the top end are vehicles modified and sold under the Holden Special Vehicle (HSV) brand.

- Compared to standard Commodores, the HSV vehicles used differently shaped parts, such as bumper bars, lights, bonnets, and grills. Many of these parts were registered designs owned by GM Global Technical Operations LLC (GMGTO).

- S.S.S. Auto Parts Pty Ltd and related entities (SSS) imported and sold replica HSV parts without Holden’s authorisation. Holden sent letters of demand to SSS and its customers, alleging the replica parts infringed GMGTO’s registered designs.

- GMGTO sued SSS for design infringement under s 71 of the Designs Act. SSS argued the parts were used to repair complex products, so the repair defence in s 72 applied.

- SSS cross-claimed against Holden for unjustified threats under s 77 of the Designs Act regarding the letters of demand it sent to its customers.

A summary of the design infringement analysis and repair defence:

- It was not disputed that the SSS parts embodied designs that were substantially similar in overall impression to GMGTO’s registered designs and that SSS had imported and sold the parts without authorisation.

- The key issue was whether GMGTO could prove SSS knew or ought reasonably to have known that the parts were not being used for the repair purpose allowed under s 72.

- GMGTO argued that various factors showed SSS knew the parts were being used to enhance vehicles rather than repair them. These included the volume of parts sold, the nature of the customers, and SSS’s later implementation of policies to restrict non-repair use.

- However, the Court found that for most of the alleged infringements, GMGTO had not discharged its onus under s 72(2) to prove SSS’s knowledge of non-repair use. The Court accepted SSS’s business focus on supplying parts for crash repairs.

- The Court found GMGTO had proved infringement for a small number of specific transactions where the circumstances showed SSS knew the parts were not being used to repair vehicles.

- Overall, the repair defence applied to most but not all of SSS’ conduct. The Court made findings on a transaction-by-transaction basis by looking at SSS’s knowledge in each case.

Considering the burden on the registered owner, Burley J held that:

… put the obligation too high. Section 72 contemplates that a part may have a dual purpose – either for a permitted repair purpose or a non-permitted purpose. That is why the knowledge component is required. The secondary materials also contemplate a dual use. On the basis of the GMH argument, any act of manufacture (one form of infringing “use”) would be likely to fail to benefit from s 72 because at the time of manufacture the part could be used for either purpose unless parts are only made to order. That cannot have been the intention of parliament. For instance, it would prevent manufacturers, importers and suppliers from maintaining an inventory of parts which can be sold, which would be impractical and also contrary to the apparent intention of the legislation.

This and similar arguments tend to distract from the enquiry required by the section. The starting point is that a product that falls within sub-sections 72(1)(a) and (b) will be capable of being used for more than one purpose; a permitted repair purpose within sub-section 72(1)(c), and a prohibited purpose, such as that alleged in the present context, the enhancement of a vehicle. It is the knowledge of the person who has imported, offered for sale or sold the product that separates the two. If in infringement proceedings an alleged infringer asserts that it had the repair purpose within sub-section 72(1)(c), then it is to be assumed that it had that purpose, unless the registered owner proves otherwise.[76]

When considering the knowledge of the alleged infringer, Burley J commented that:

A manufacturer is highly unlikely to know, at the point that the part comes off the production line, what will ultimately become of it. In the normal flow of commerce, the manufacturer will no doubt sell to a wholesaler, which in turn will sell to a retailer, which in turn will sell to a user. There is no direct link between the infringing act and its ultimate use (the remoteness problem). When the act of making is complete, the manufacturer is unlikely to have any real idea of its ultimate fate. But that is unimportant. The defence is not concerned with the actual use of the part, but the purpose of the manufacture (or other use). What did the manufacturer intend by manufacturing the part? The same observations may be made in relation to other acts of use, although the remoteness problem is more acute at the point of manufacture of a part, and less acute at the retail sale point when the seller is more likely to be dealing directly with the ultimate user.[77]

Special Considerations in Design Infringement

The application of design infringement principles must often consider special considerations that reflect the complex realities of modern commerce and manufacturing. These considerations include the challenges posed by parallel imports, and the interaction between design rights and other forms of intellectual property protection.

Parallel Importation

Parallel importation is the importation of products that embody a registered design that has been manufactured overseas with permission of the registered design owner but are imported into Australia outside of the manufacturer’s official distribution channels.

For example, Acme Pty Ltd is the registered owner of a design for a water pitcher. It has registered the design in Australia and New Zealand and sells the product in those countries. However, Agatha Pty Ltd begins to import the product from New Zealand to Australia at a lower price. These products are sometimes known as ‘grey market goods’.

The Act permits parallel importation through section 71(2), which provides a defence against design infringement for products that legitimately embody a registered design by or with the consent of the design owner. This means that once genuine design products are placed on the market anywhere in the world with the design owner’s consent, the owner’s rights are considered ‘exhausted’, preventing claims of secondary infringement due to the importation and sale of the product in Australia. This provision is similar to that in the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth).[78]

(2) Despite subsection (1), a person does not infringe a registered design if:

(a) the person imports a product, in relation to which the design is registered, which embodies a design that is identical to, or substantially similar in overall impression to, the registered design; and

(b) the product embodies the design with the licence or authority of the registered owner of the design or an exclusive licensee.

In the example above, Agatha Pty Ltd would not be infringing the registered design in Australia. However, this creates tension for Acme as it competes for the same product. As a result, Acme may not be able to price its goods higher than Agatha. This outcome could be favourable for consumers, as they still receive genuine design products through alternative distribution channels that may offer better prices.

Exhaustion of Rights

One matter not directly dealt with under the Act is whether the registered owner’s rights are ‘exhausted’ once a product embodying a registered design is sold to a consumer. For example, consider company MobileTech Pty Ltd has a registered and certified design for a unique smartphone charging dock. The design’s visual features include a distinctive curved base and an innovative cable management system integrated into its appearance. The company manufactures and sells these docks through authorised retailers in Australia. Consumer A legitimately buys one of these docks from an authorised Sydney retailer. After using it for six months, Consumer A decides to sell the dock through an online marketplace to Consumer B in Melbourne. Would Consumer A be infringing MobileTech Pty Ltd’s rights in the design?

Section 122A was added to the Trade Marks Act 1995 (Cth) to address this point specifically and is relevant to parallel importation. A person will not infringe on a registered trade mark if, after making ‘reasonable enquiries’, a reasonable person would conclude that the trade mark had been applied to the goods with the consent of:

- the trade mark owner;

- an authorised user;

- a person permitted to use the trade mark;

- a person permitted by an authorised user’

- someone with significant influence over the use of the trade mark; or

- an associated entity of any of those persons.

Examining the provisions under the Designs Act 2003 (Cth), Dowsett J in Austshade Pty Ltd v Boss Shade Pty Ltd noted:[79]

Section 10 of the Designs Act expressly confers the exclusive right to “make”, to “use” and to “sell” a product embodying the relevant design. Whilst the word “exercise” is not used, I have little difficulty in concluding that s 10(1), read as a whole, would include anything which might conceivably have been described by that word. Hence, I conclude that the decision in National Phonograph applies to the sale of a product embodying a registered design.

The decision referenced in Dowsett J’s judgment is a High Court decision in patents relating to the prevailing implied licence doctrine in Australian law.[80] The principle meant that the sale of a patented product by or with the patent owner’s consent includes an implied licence that allows the purchaser to use the product as they see fit without infringing the owner’s rights. At that time, the application of the doctrine, therefore, would limit a registered design owner’s ability to enforce its rights against a purchaser of a product that embodies a design.

However, more recently, in Calidad Pty Ltd v Seiko Epson Corporation, the High Court, in a patent case, expressed that the decision in National Phonograph Co of Australia Ltd v Menck (1908) 7 CLR 481 should no longer be followed and that exhaustion of rights doctrine should have the ‘virtues of logic, simplicity and coherence with the legal principle’.[81] The doctrine means that a patent owner’s rights come to an end when the patented product is first sold by, or with the authorisation of, the owner.

Using the example from above, when MobileTech first sold the dock through their authorised retailer, they received compensation for their design rights in that specific physical product. This “first sale” would likely exhaust MobileTech’s right to control further distribution of that particular unit. Consumer A should be free to resell their legitimately purchased dock without infringing upon MobileTech’s design rights.

Other IP Rights

The interaction between design rights and other forms of intellectual property protection often requires careful consideration. As discussed in more detail in Chapter 9, a single product might embody multiple forms of intellectual property, including designs, patents, trade marks, and copyright. Understanding how these different rights interact and how they might be enforced together or separately is crucial for an effective intellectual property strategy.

Infringement Proceedings

Design infringement proceedings require careful attention to both procedural and substantive matters. These proceedings typically commence in either the Federal Court of Australia or the Federal Circuit Court, although State and Territory Supreme Courts also have jurisdiction to hear such matters. The choice of forum often depends on factors such as the complexity of the case, the relief sought, and practical considerations like cost and timing.

Importantly, section 71 establishes a statutory limitation period to bring infringement proceedings. Specifically, these proceedings must be initiated within six years from the day the alleged infringement occurred. It is crucial to remember that the acts of infringement must have occurred during the registered designs’ term of protection.[82]

Standing

Standing to commence proceedings is limited to specific parties under the Act. The registered owner has the primary right to bring proceedings. Following amendments to the Act, exclusive licensees may also initiate proceedings in their own name, though they usually must join the registered owner as a party.[83] Where there are multiple owners, any one owner may initiate proceedings, though court permission may be required if co-owners do not agree to the action.

Read

DESIGNS ACT 2003 – SECT 73

Infringement proceedings

(1) The registered owner of a registered design, or an exclusive licensee, may bring proceedings against another person alleging that the person has infringed the registered design.

(2) Infringement proceedings may be brought in a prescribed court or in another court that has jurisdiction in relation to the proceedings.

(2A) If an exclusive licensee brings infringement proceedings, the licensee must make the registered owner of the registered design a defendant in the proceedings, unless the registered owner is joined as a plaintiff.

(2B) If the registered owner of the registered design is made a defendant in the proceedings, the registered owner is not liable for costs if the registered owner does not take part in the proceedings.

(3) Infringement proceedings may not be brought under subsection (1) until:

(a) the design has been examined under Chapter 5; and

(b) a certificate of examination has been issued.

(4) If a person files an application under section 21 for registration of a design as a result of the operation of section 55, the person may only bring infringement proceedings in respect of infringements of the design occurring after the date on which the application was filed under section 21.

DESIGNS ACT 2003 – SECT 5B

Definition of exclusive licensee

(1) For the purposes of this Act, an exclusive licensee is a licensee under a licence granted by the registered owner of a registered design that confers on the licensee, or on the licensee and persons authorised by the licensee, the exclusive rights in the design mentioned in paragraphs 10(1)(a) to (e) to the exclusion of the registered owner and all other persons.

(2) Subsection (1) applies whether or not the licence also confers on the licensee the exclusive right in the design mentioned in paragraph 10(1)(f) to the exclusion of the registered owner and all other persons.

Prescribed Courts

The conduct of proceedings generally follows a structured pathway through the courts. The process begins with filing originating documents — that is, a statement of claim detailing the registered design, the alleged infringing conduct, and the relief sought. The respondent then has the chance to file a defence, which often includes a counter-claim for the revocation of the design registration. This combination of infringement action and validity challenge is characteristic of intellectual property litigation.

Read

DESIGNS ACT 2003 – SECT 83

Jurisdiction of Federal Court

(1) The Federal Court has jurisdiction with respect to matters arising under this Act.

(2) The jurisdiction of the Federal Court to hear and determine appeals from decisions of the Registrar is exclusive of the jurisdiction of any other court other than the jurisdiction of:

(a) the Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia (Division 2) under subsection 83A(2); and

(b) the High Court under section 75 of the Constitution.

(3) A prosecution for an offence against this Act must not be brought in the Federal Court.

DESIGNS ACT 2003 – SECT 83A

Jurisdiction of the Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia (Division 2)

(1) The Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia (Division 2) has jurisdiction with respect to matters arising under this Act.

(2) The jurisdiction of the Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia (Division 2) to hear and determine appeals from decisions of the Registrar is exclusive of the jurisdiction of any other court other than the jurisdiction of:

(a) the Federal Court under subsection 83(2); and

(b) the High Court under section 75 of the Constitution.

(3) A prosecution for an offence against this Act must not be brought in the Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia (Division 2).

DESIGNS ACT 2003 – SECT 84

Jurisdiction of other prescribed courts

(1) Each prescribed court other than the Federal Court or the Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia (Division 2) has jurisdiction in respect of matters arising under this Act in relation to which proceedings may be brought in a prescribed court.

(2) The jurisdiction conferred by subsection (1) on the Supreme Court of a Territory is as follows:

(a) the jurisdiction is conferred to the extent that the Constitution permits so far as it relates to:

(i) infringement proceedings; or

(ii) an application for revocation of registration of a design because of section 74; and

(b) in any other case, the jurisdiction is conferred only in relation to proceedings instituted by:

(i) a natural person who is resident in the Territory at the time the proceedings are brought; or

(ii) a corporation that has its principal place of business in the Territory at the time the proceedings are brought.

(3) This section, so far as it relates to the Supreme Court of Norfolk Island, has effect subject to section 60AA of the Norfolk Island Act 1979.

Evidence in design proceedings often includes a combination of factual and expert testimony. Factual evidence may address matters such as the design’s development, circumstances of alleged infringement, and any relevant commercial dealings. Expert evidence often plays a crucial role, particularly in assessing substantial similarity and applying the perspective of the familiar person. The Federal Court’s practice note on expert evidence provides important guidance on how this evidence should be prepared and presented.[84]

Transfer of proceedings

Section 86 permits transferring proceedings under the Act to another prescribed court with jurisdiction. Transfers from the Federal Court to the Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia (Division 2) are allowed when appropriate.[85]

Read

DESIGNS ACT 2003 – SECT 86

Transfer of proceedings etc.

(1) A court in which proceedings have been brought under this Act may transfer the proceedings to another prescribed court having jurisdiction to hear and determine the proceedings:

(a) if the court thinks fit; and

(b) upon application of a party made at any stage in the proceedings.

(2) If proceedings are transferred from one court to another court under this section:

(a) all documents of record relevant to the proceedings are to be sent to the Registrar or other appropriate officer of the other court; and

(b) the other court must proceed as if:

(i) the proceedings had been started in that court; and

(ii) the same steps in the proceedings had been taken in that court as had been taken in the transferring court.

(3) This section does not apply in relation to a transfer of proceedings between the Federal Court and the Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia (Division 2).

Interlocutory proceedings often play a significant role in design cases. Applications for interim injunctions are likely sought if there is ongoing infringing conduct, including the importation and selling of products embodying the design. An applicant seeking interlocutory injunctive relief must demonstrate that:

- there is a serious question to be tried as to the applicant’s entitlement to relief;

- the applicant is likely to suffer injury for which damages will not be an adequate remedy; and

- the balance of convenience favours the granting of an interlocutory injunction.[86]

For example, Transportable Shade Sheds Australia Pty Ltd v Aussie Shade Sheds Pty Ltd,[87] provides insight into how courts assess applications for urgent interlocutory injunctions in design infringement cases. The applicant sought an ex parte injunction to restrain the alleged infringement of its registered designs for shade shed components, which it had acquired through a liquidator’s sale. Justice Collier applied the test from Australian Broadcasting Corporation v O’Neill,[88] finding: (1) there was a serious question to be tried regarding infringement under s 71 of the Designs Act based on evidence the respondent was using identical designs; (2) damages would not be adequate given the ongoing nature of the infringement; and (3) the balance of convenience favoured granting the injunction given evidence of continued use of the applicant’s confidential material.[89] The case illustrates how courts weigh evidence of design infringement when considering urgent injunctive relief, even in ex parte applications.

Appeals Process

Appeals from decisions in infringement proceedings typically lie to the Full Federal Court from decisions of the Federal Court, which may have also originated from the Federal Circuit Court. Further appeals to the High Court require special leave and are rare in design cases.[90] The appellate courts have played an important role in developing principles of design law.

Read

DESIGNS ACT 2003 – SECT 87

Appeals

(1) An appeal lies to the Federal Court from a judgment or order of:

(a) another prescribed court exercising jurisdiction under this Act; or

(b) any other court in a proceeding referred to in section 73 or 77.

(2) An appeal does not lie to the full court of the Federal Court from a judgment or order of a single judge of the Federal Court or the Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia (Division 2), in the exercise of its jurisdiction to hear and determine appeals from decisions of the Registrar, other than with the leave of the Federal Court.

(3) An appeal lies to the High Court, with special leave of the High Court, from a judgment or order referred to in subsection (1).

(4) No appeal lies from a judgment or order referred to in subsection (1), except as provided by this section.

Remedies

The remedies available in design infringement proceedings reflect both the proprietary nature of design rights and the commercial context in which they operate. Section 75 provides a framework of remedies while also allowing courts considerable discretion in crafting appropriate relief for particular cases.

Read

DESIGNS ACT 2003 – SECT 75

Remedies for infringement

(1) Without limiting the relief that a court may grant in infringement proceedings, the relief may include:

(a) an injunction subject to such terms as the court thinks fit; and

(b) at the option of the plaintiff–damages or an account of profits.

Relief for defendant–infringement before date of registration

(1A) To the extent that the infringement proceedings relate to an infringement occurring before the date on which the design was registered, the court may:

(a) refuse to award damages; or

(b) reduce the damages that would otherwise be awarded; or

(c) refuse to make an order for an account of profits;

if the defendant satisfies the court that, at the time of the infringement, the defendant was not aware, and could not reasonably have been expected to be aware, that an application in respect of the design had been filed under section 21.

Relief for defendant–infringement on or after date of registration

(2) To the extent that the infringement proceedings relate to an infringement occurring on or after the date on which the design was registered, the court may refuse to award damages, reduce the damages that would otherwise be awarded, or refuse to make an order for an account of profits, if the defendant satisfies the court:

(a) in the case of primary infringement:

(i) that at the time of the infringement, the defendant was not aware that the design was registered; and

(ii) that before that time, the defendant had taken all reasonable steps to ascertain whether the design was registered; or

(b) in the case of secondary infringement–that at the time of the infringement, the defendant was not aware, and could not reasonably have been expected to be aware, that the design was registered.

Additional damages

(3) The court may award such additional damages as it considers appropriate, having regard to the flagrancy of the infringement and all other relevant matters.

Prima facie evidence

(4) It is prima facie evidence that the defendant was aware that the design was registered if the product embodying the registered design to which the infringement proceedings relate, or the packaging of the product, is marked so as to indicate registration of the design.

Definitions

(5) In this section:

“primary infringement” means infringement of a kind mentioned in paragraph 71(1)(a).

“secondary infringement” means infringement of a kind mentioned in paragraph 71(1)(b), (c), (d) or (e).

Injunctions

Injunctive relief is often the primary remedy sought in design proceedings. Final injunctions prevent future infringement and provide the design owner with practical protection of their exclusive rights. Courts must balance protecting the design owner’s rights against the risk of unnecessarily constraining legitimate commercial activity.

For example, GME Pty Ltd v Uniden Australia Pty Ltd (No 2), Burley J ordered an injunction.[91] The order included the Respondent be restrained, whether by itself, its directors, servants, agents, related bodies corporate or otherwise, for as long as the GME Design remains registered on the Register of Designs, from infringing the GME Design, including by:

(a) making or offering to make the XTRAK Products or either of them;

(b) importing the XTRAK Products or either of them into Australia for sale, or for use for the purposes of any trade or business;

(c) selling, hiring or otherwise disposing of, or offering to sell, hire or otherwise dispose of the XTRAK Products, or either of them;

(d) using the XTRAK Products or either of them in any way for the purposes of any trade or business; or

(e) keeping the XTRAK Products or either of them for the purposes of doing any of the acts in order 3(c) or order 3(d),

without the licence or consent of the Applicant.[92]

Damages

The assessment of monetary remedies presents particular challenges in design cases. The successful plaintiff may elect between damages and an account of profits,[93] though this election must typically be made before the quantum is determined. Damages seek to compensate the design owner for losses suffered due to the infringement, including lost sales or lost licensing opportunities. The quantification of such losses often requires detailed economic evidence and consideration of hypothetical scenarios about what would have occurred without the infringement.

In Review 2, although the Court ultimately dismissed both the infringement claim and cross-claim for invalidity, Kenny J considered how damages would have been assessed had infringement been established. The applicants sought damages of $18,919.25 for lost sales (based on 133 units at $142.25 profit per garment), $200,000 for loss of reputation and position in the Australian market, and $400,000 in additional damages. Justice Kenny rejected the basis for calculating lost sales, finding no evidence that Redberry’s garments adversely affected Review’s sales. Instead, Her Honour suggested that if the infringement had been proven, damages would have been assessed at $3,500 based on the diminution in value of the Review Design as a choice in action. The Court also found that additional damages under s 75(3) would not have been warranted, as Redberry’s conduct could not be considered flagrant given their ignorance of Review’s design rights.

Some cases consider ‘reputational damage’ to be a component of damages. Such damage reflects the unique nature of designs concerning their communicative features to consumers. In Review Australia Pty Ltd v New Cover Group Pty Ltd, Kenny J was prepared to accept the ‘exclusivity’ of the owner’s design – that is, commercially valuable to the owner. Her Honour assessed the “effect of the infringement on the value of Review Design as a choice in action at $35,000.”[94] To show the exclusivity of a design, evidence of sales through the plaintiff’s stores or high-end retailers would assist the court.

Account of Profits

An account of profits provides an alternative monetary remedy, focusing on the profits the infringer derived from the infringing conduct rather than the design owner’s loss. This remedy can be particularly attractive when the infringer’s profits exceed the owner’s likely damages or when damages are difficult to prove. However, the complexity of apportioning profits to the infringing aspect of a product can present significant practical challenges.

Additional Damages

Additional damages for particularly egregious infringement may be awarded under section 75(3) of the Act. The court may consider factors such as the flagrancy of the infringement, the need for deterrence, and any benefits shown to have accrued to the infringer. This provision allows courts to impose larger monetary remedies when ordinary compensatory damages might be insufficient.

A finding needs clear evidence to support a claim of ‘flagrancy.’ In Review Australia Pty Ltd v New Cover Group Pty Ltd, Kenny J found that there was no flagrancy on the part of the defendant due to a lack of evidence.[95] At the time of the infringement, no one knew about the registered design, and they ceased activity after becoming aware of the infringement claim.

Her Honour also rejected the applicant’s claim that additional damages should be awarded because of how close the two designs were. Kenny J said:[96]

In the designs context, copying per se is not, however, unlawful and does not establish a design infringement. There is nothing relevantly reprehensible in this business practice providing it does not result in design infringement. Accordingly, copying alone does not attract additional damages. Copying resulting in design infringement can, of course, justify an award of general damages, but, in general, such copying must be flagrant to justify additional damages. I have found, however, that the copying in this case was not flagrant.

Continued trading after notification of an infringement claim was a relevant matter to Jessup J in Review Australia Pty Ltd v Innovative Lifestyle Investments Pty Ltd (2008) 166 FCR 358, although only justifying here a sum of $10,000.

In PositiveG Investments Pty Ltd v Li,[97] PositiveG Investments was the owner of two registered designs for display units used in dual battery volt meters for motor vehicles, which they discovered were being copied and sold by the respondent Li on eBay under various listings. Despite being notified of PositiveG’s rights, Li continued to sell the infringing products under different item numbers and failed to participate in the proceedings, leading the Court to grant summary judgment finding infringement of both designs and awarding compensatory damages of $7,175.55 plus additional damages of $25,000.

Judge Baird awarded additional damages of $25,000 under s 75(3) of the Designs Act 2003, despite the applicant seeking $30,000.[98] Her Honour emphasised that additional damages need not be proportionate to compensatory damages and serve to mark the Court’s disapproval of infringing conduct.[99] The award was justified by the respondent’s flagrant conduct, including: repeatedly ignoring notifications of PositiveG’s rights, failing to participate in proceedings, continuing to sell infringing products under different item numbers even after being made aware of the registered designs, and only partially removing some infringing listings while maintaining others. Her Honour noted that the substantial amount aimed to signal to others in the marketplace that design infringement is the conduct of which the Court expresses clear disapproval.[100]

Innocence

The Designs Amendment (Advisory Council on Intellectual Property Responses) Act 2021 (Cth) amended this section and introduced subsection 1A to expand the ‘innocent infringer’ defence. This provision specifically covers situations where infringement occurs while a design is not publicly available – that is, between the date a design application is filed and its subsequent registration.