1 An Introduction to Design and the Legal Protection for Designs

Mitchell Adams

Contents

Much thought goes into what we interact with — from the chairs we sit in, the smartphones we carry and the cars we drive. All human-made objects are designed objects. Design is, therefore, omnipresent. It has shaped our material culture since the earliest of times and remains a crucial aspect of all our lives. Through each carefully designed object, we experience the world around us. However, the term ‘design’ can elude many of us when we attempt to define it and explore its meaning.

The term ‘design’ has many different meanings depending on the context in which it is used. Design can refer to the art of making anything.[1] When we say anything, we mean everything. We design everything from physical products (such as furniture, buildings or garments) to digital elements (such as graphical user interfaces) and even whole systems. The term commonly refers to the plan or sketch to make any of these items.[2] In addition, it can refer to an object’s nature, purpose or intention.[3] Design is also a process. Designers plan with a specific purpose or intention in mind when creating.[4] There are many different ways or methods to design. Many may be familiar with ‘design thinking’ as a problem-solving method.[5]

Design is not only the conception and planning of all human-made things but also the physical outcome of the process.[6] ‘To design’, therefore, can involve combining artistic, technical, and business skills to balance aesthetics and functionality.[7] Designers are practitioners who study art, science, and human behaviour to understand the world’s workings and apply what they learn to solve problems.[8]. Lawyers take a narrower view of design, perceiving it as a “blend[ing] the efficiency of the article for its purpose with the appeal which the finished product must make to the eye of its observer”.[9]

Design can be thought of as the meeting of art and science. Considerations of a product’s form and function intertwine to create useful items.[10] Another interpretation is that designs are the form characteristics of a product (or even a range of related products) that shape a person’s sensory experience when interacting with it.[11] A product bearing the design can provide its user with functional or symbolic benefits.[12] In addition, design can create a visual language that can help communicate, telling an end-user what to expect of the product’s function or the sensory experience. It helps to visually differentiate one product from others that may have the same function.[13]

Products that often do not have much scope for technical innovation can be designed in new and distinctive ways. Take, for example, the Australian designer Marc Newson’s Lockheed lounge chair. A lounge chair cannot be changed too much to achieve its intended function. However, Newson’s design, featuring only three legs and an aluminium body, subverted the conventions of 1980s furniture design. The lounge chair was featured in Madonna’s video for the single ‘Rain’ and is considered one of the most recognisable pieces of contemporary furniture design.[14]

As a science, design methods and processes can involve conducting research, collecting information, analysing data and communicating results.[15] The process can often require collaboration between designers, stakeholders, end-users, engineers, and other professionals to ensure that the resulting design meets the needs of its intended audience.[16] Ultimately, design aims to create aesthetically pleasing items while considering efficiency, usability, and sustainability.

Traditionally, designers were considered generalists who solved problems of the day.[17] Over time, however, the volume and complexity of design knowledge have increased, leading to specialisations.[18] The design process can be applied to various areas, including architecture, fashion, graphic design, and industrial design.

Do

Explore the interactive below that shows the various fields of design activity.

Design activity is vast and constantly growing and evolving. The goal of this book, however, is to explore what the law considers to be a protectable design – those that the law grants exclusive rights to. The scope of protection afforded to design under the law is narrow compared to the more extensive understanding of design. The intellectual property protection for designs is for the appearance of a physical product. A design is the ‘overall appearance of the product resulting from one or more visual features of the product’.[19] Those features include the product’s shape, configuration, pattern or ornamentation, but not how it feels, what it is made of, or how it works.[20] The protection of designs is governed under the Designs Act 2003 (Cth). Under the Act, designs must be new and distinctive to be registered and confirmed to have exclusive rights to their use and exploitation. Each of these concepts will be unpacked and explored in this textbook.

Intellectual Property Protection for Designs

If we accept that design is not only the conception and planning of all human-made things but also the outcome of the creative process of generating those objects, where does intellectual property protection fit in? Intellectual property refers to ‘… creations of the mind, such as inventions; literary and artistic works; symbols; names and images used in commerce’.[21]

Intellectual property law is an umbrella term that describes the legal frameworks that provide creators and innovators exclusive rights to their creations. The subject matter of intellectual property law is well-known and, at times, attracts controversy. Copyright, patents and trade marks are readily recognised and discussed, although sometimes misdescribed or incorrectly identified.[22] Some categories require registration with the Australian Government agency IP Australia (patents, trade marks, designs and plant breeders’ rights), while protection arises as a matter of law for others (copyright, trade secrets and circuit layouts). For centuries, the law surrounding intellectual property was thought of as confirming their own separate boundaries to which intellectual endeavour or innovation would fit.[23] Intellectual property rights take various forms, some more familiar than others. The categories of intellectual property include:

- Patents

- Trade marks

- Designs

- Plant Breeders Rights

- Copyright

- Trade Secrets

- Circuit Layouts

The categories of intellectual property, IP Australia (CC-BY 4.0)

Do

To explore the various categories of intellectual property, use the directional buttons in the presentation below which provide more detail on each category:

After learning about the different categories of intellectual property, test your knowledge and see which intellectual property rights subsist in lawnmowing. Match the different forms of intellectual property rights with the various aspects of the lawnmower.

Historically, the landscape of intellectual property rights was considered a ‘small, well-ordered, simple walled garden’.[24] Copyright, trade marks and patents came first and remained well-trimmed.[25] Over time, the existing intellectual property rights grew out of their boundaries, and new rights were added. As the boundaries crumbled, overlaps between the various intellectual property overlaps emerged. Several intellectual property rights can, therefore, co-exist in a single product. Take, for example, the smartphone.

Do

Click on the areas of the smartphone in the interactive below to explore what kinds of intellectual property rights exist in one product.

The protection of designs within the landscape of intellectual property rights has always been met with cynicism. The intellectual property protection for designs attempts to draw a distinction from the artistic nature of design.[26] Academics have often observed that design protection is the “stepchild of patents and copyright”.[27] In part, this observation is correct. The design process is at the intersection of invention and creativity. Products with limited scope for technical innovation (where technological development would be protected under a patent right) can be reinvented in new ways for consumers.[28]

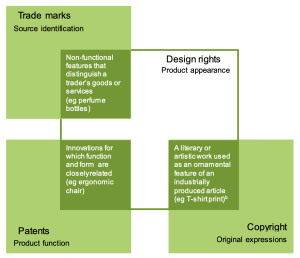

The growth of intellectual property law in the latter part of the twentieth century is best seen through the lens of design protection. Design rights can sit across or overlap with the other concepts in intellectual property. As the smartphone example above shows, the boundaries of intellectual property protection can co-exist within a single product and, at times, start to overlap. The Productivity Commission, in its 2016 report into Australia’s intellectual property arrangements, identified that design rights overlap with trade marks, patents and copyright in the following ways.[29]

The overlaps between designs and other intellectual property rights will be discussed in more detail in Chapter 9.

Protection for Designs in Australia

Watch

First, watch the short video below, which provides a short overview of how designs are protected in Australia.

The protection of designs in Australia is governed by the Designs Act 2003 (Cth).[30] The Act establishes a system for the application, registration and protection of new and distinctive designs. Under the Act, a ‘design’ has a precise meaning, defining what is protectable. A design right protects the overall visual appearance of a physical product resulting from one or more visual features of a product,[31] including the shape, configuration, pattern and ornamentation of the product.[32] A ‘product’ is defined as a thing that is manufactured or handmade.[33] Designs registered under the system are published on the Australian Designs Register.

Do

Use the interactive below to explore the features of a registered design. Click on the buttons for an explanation of each piece of information contained in the Register.

Notably, the concept of ‘design’ under the Act focuses on the design applied to a product, giving it a distinctive overall appearance. It involves the visual features of products in two-dimensional (pattern or ornamentation) or three-dimensional (shape and configuration) form.[34] For example, the former would include fabric designs that could be applied to a garment, while the latter would involve the shape of a chair. Exclusive rights to the design are only afforded to the individual and specific appearance of the product that is intended to be commercially produced.[35] Ultimately, what is protected under the Act are those designs applied to a product to give it a distinctive visual appearance as opposed to the plan or method of making the product.[36] The focus of designs law is, therefore, on the physical outcome of the creative process of generating those objects.

The specific focus on protecting the appearance of a physical product manufactured or handmade has its origins in the Industrial Revolution, with the mass production of goods and the division of labour. The Industrial Revolution saw the introduction of specialised machinery and specialised labour workers to achieve technical and productivity results. As a result, the design of these objects became a separate specialised activity from the production stages of manufacturing.[37] Industrial design was thus born and formed a part of the process of manufacturing and marking mass-produced goods. That effort was then rewarded with exclusive rights.

Rights to the design are afforded to those who created the design or those who may derive the title from the design.[38] To obtain a design right to the design, the owner must register the design with IP Australia. A design right granted under the Act is sometimes referred to as a monopoly in the design.[39] However, calling it a monopoly is overstating it. A right granted under the Act provides the owner exclusive use of the design (and those similar to it) for ten years. The owner of a registered design has the exclusive rights to:

- Use the design within Australia;

- Authorise others to use the design within Australia;

- Assign or licence the use of the design within Australia; and

- Apply for protection overseas for the same design and maintain the same priority date (explained below).[40]

A design right for the appearance of a smartphone will prevent others from making smartphones with the same or substantially similar smartphone. To enforce any exclusive rights in a design, it first must be assessed as to whether the design is eligible for protection under the Act. Only new and distinctive designs are protected under the Act (discussed in Chapter 5).[41] A registered design, however, will not prevent anyone from making smartphones more generally. The focus is on the appearance of the smartphone.

Registering a design, therefore, becomes essential for designers to protect their intellectual effort in the design. The process, however, is not straightforward. Under the Act, an applicant must follow a two-step process to protect their designs — a registration process followed by a certification process (both processes are detailed in Chapter 2). A certified design gives the owner the right to enforce the exclusive rights under the Act against others using the same or substantially similar design.

The terminology at this point becomes a little confusing. When an applicant applies to IP Australia to register a design, it becomes ‘registered’ after passing a formalities assessment. This process involves checking the details in the application have been correctly supplied. At this point in the process, IP Australia does not check whether the design is eligible for protection under the Act. The applicant must separately request an examination of the design and be issued a certificate of examination — also known as certification. The applicant must go through both steps to close the loop. The process has been identified as a key issue with the low uptake of design protection in Australia.[42]

Justification for Protecting Designs

But what is the purpose and function of design law? Unlike most other areas of intellectual property, no clear principle explains the need for the Australian design system. Rather, the present design system is widely criticised for lacking any rational basis,[43] and for being confusing.[44]

Intellectual property rights offer opportunities for creators of new and valuable knowledge to secure sufficient returns to motivate their initial endeavour or investment.[45] The broad purpose of the intellectual property system is to provide ‘… appropriate incentives for innovation, investment and the production of creative works while ensuring it does not unreasonably impede further innovation, competition, investment and access to goods and services’.[46] Trade marks, for example, are signs used in the course of trade to indicate origin, serve an economic function by reducing consumer search costs, and protect consumers against consumer confusion. This, in turn, incentivises firms to invest resources in developing and maintaining a strong mark which maintains consistent quality.[47] Patent law provides a legally enforceable right to commercially exploit new and inventive devices, substances, methods and processes — and is designed to stimulate and incentivise innovation and promote research and development.[48] Copyright law, which protects various original forms of expression, can also serve as an incentive for creative expression while rewarding authors for the fruits of their labour.[49]

The role and contribution of design rights have a unique place in Australia’s intellectual property system. However, there are differing views on why we provide legal protection to designs. When introducing the new registration system under the Designs Act 2003 (Cth), the predominant objective was to address industry concerns about an inefficient design registration system and replace the decades-old Designs Act 1906 (Cth).[50] The Explanatory Memorandum specifically called out the rationale for the new system, ‘… to encourage innovation by giving designers the exclusive right to exploit their designs for a limited time and prevent competitors free-riding on design innovations’.[51] This objective reflects the predominant economic rationale for providing intellectual property rights.

An alternative view can be taken from the perspective of someone whose intellectual effort is in question. A designer may have a natural right to their design, rewarding their skill, effort and labour in producing it.[52] This view is reflected in Article 27(2) of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights: ‘Everyone has the right to the protection of the moral and material interests resulting from any scientific, literary or artistic production of which he [sic] is the author’.[53] The personality theory view would argue that design protection is justified because the designer’s work is an extension of their person. A utilitarian approach to protecting designs would seek to have laws that balance the incentives for designers to produce useful articles for society while balancing this against the right of the public to access intellectual property.[54] This approach for the greatest good for the greatest number is best reflected in defences to design infringement (covered in more detail in Chapter 10).

Although these rationales are each valid and can be seen within different facets of design law, the currently accepted rationale is the economic rationale. The Australian government has articulated that our intellectual property systems should ‘provide appropriate incentives for innovation, investment and the production of creative works while ensuring it does not unreasonably impede further innovation, competition, investment and access to goods and services’.[55]

There are two economic views that support protecting designs: (i) providing incentives to encourage design innovation and (ii) protecting the communication role design plays in differentiating products in the marketplace.[56] The incentive view of protecting designs is reflected in the objective when the Designs Bill 2002 was introduced. Planning, developing and commercialising a design is inherently risky — it involves investment and risk.[57] A successful design is determined by a mixture of novelty and usefulness of a design as well as the subjective opinions of both critics and consumers of the product.[58] When the design goes public, it can be easily copied. Without exclusive control, there could be less motivation to invest in original and distinctive designs. The limit placed on the exclusive rights to a design of 10 years reflects a public interest in the design process and its protection. Designs made available after the term and moving into the public domain permit others to build upon the innovation of others.

From a design theory perspective, designs also communicate to consumers. The design informs its end-user information, including its attributes, cultural and social values and know-how.[59] In addition, the sensory experience offered by design can help customers differentiate between products — helping identify their origin or quality.[60] For example, the dynamic island of the Apple iPhone can help customers differentiate the iPhone from other smartphones on the market.

If the owner does not have exclusive rights to the design and it is copied, consumers may not be able to determine the origin of the product bearing the design. The protection afforded to such a design can reduce this confusion. Given such an effect, this rationale shares the same basis as trade mark law. Moreover, product design can be shared across a product line. For example, the bevelled corners of Apple’s electronics are common across multiple products with a screen (e.g., iPhone and iPad). The design can convey information about the product’s quality to consumers. Copying this design can again lead to consumer confusion and diminish the value of the design.[61] Protecting designs can, therefore, increase market transparency and create more market efficiency by allowing designers to control the information conveyed to consumers. Consumers can then more easily navigate the marketplace for products they desire based on their attributes and expected sensory experience.

The Criticism of Designs Law – A Mismatch Between What is Design and its Protection

It is no secret that the intellectual property protection for design has not kept up with changes in the scope of what designers are doing. One of the enduring issues in this area of intellectual property law is what sort of design activity falls under the scope of protection.[62]

As discussed above, the concept of design can cover the conception and planning of an object as well as the outcome of the process. The outcome can be physical or even digital (for example, video game design). In addition, the characteristics of the resulting product, which shape the sensory experience of a product, are also part of the design.[63] Meanwhile, the law defines a design as the visual features of products, such as their shape, configuration, pattern, and ornamentation. This definition reflects the origins of designs law (discussed in Chapter 2) and focuses on the physical outcome of the design process (discussed in Chapter 3).

The subject matter capable of protection has ‘… always been a matter of considerable difficulty’.[64] These concerns extend to the scope and extent of protection as well as the relationship between design protection and other intellectual property regimes, especially artistic copyright works and, in more recent times, three-dimensional trade marks.[65]

History may show that reform in this area may take a long time to materialise. Compared to the other intellectual property regimes, Australian design law has remained relatively stagnant.[66] The other areas of intellectual property have been constantly developing to adapt to technological and cultural changes. In comparison, it took nearly a century for the law of designs to be overhauled by Parliament with the introduction of the Designs Act 2003 (Cth) replacing the Designs Act 1906 (Cth). However, the amount of time and effort that was expended to reform the system has been high.

Professor Ricketson found this particularly interesting, especially since the rates of registering designs are lower compared to the other intellectual property rights. He notes: “No other single issue in the intellectual property lexicon seemed so riven by controversy and the taking of irrevocable, even quasi-theological, positions.”[67] Ricketson has attributed the source of the conflict to issues that go far beyond the registered designs system but to the importance of intellectual property as a whole.[68] Alternatively, Professor Lahore has pointed to two factors going to the heart of the dilemma for design reform:

(a) differing in views between copyright-minded and patent-minded reformers; and

(b) historical origins of designs as a patent-type industrial right with lurches into copyright.[69]

Concerns about the scope of protection afforded to designs are the likely result of the mismatch between the general understanding of what design is and its legal definition.

Design-related activities have broadened since the Industrial Revolution. The commercial role and significance of design have increased exponentially. It is widely accepted now that design plays a significant role in corporate strategy and consumer preferences. It is essential to attract or excite customers to form attachments to products and maintain a competitive advantage.

The contribution of design activity can also now be quantified. IP Australia estimated that the contribution of design-related industries and workers to Australia’s Gross Domestic Product was AU$67.5 billion per annum (more than 3.5% of GDP).[70] This contribution is equivalent to the size of the construction industry.[71] Design, therefore, plays a large role in the Australian economy.

Design can be the cornerstone of a product’s success. By creating new designs that improve a product’s performance, enhance its aesthetics, or strengthen a user’s connection with a brand, businesses can stay ahead of the curve and outperform their competition.[72] The intellectual property protection for designs is based on the output of this kind of activity. However, design extends beyond the final product and its visual appearance. There are many more attributes that are part of a product’s design, including its function, durability, accessibility, ease of use, value for money, safety, ergonomics or sustainability. Many of these attributes are born out of the design process and likely involve the role of constraints desired for the final product.[73]

This tension or mismatch between the broader understanding of the role of design and the legal definition of design has routinely been identified as a reason why there is little uptake of design rights in Australia. IP Australia identified in a study that nearly half (47%) of the industry respondents indicated they do not typically seek protection for their designs.[74] Many individuals who participated in IP Australia’s survey stated that they were not even aware of design rights. However, among those who did seek formal protection, design rights were viewed as the most crucial form of protection. Those who did not opt for formal protection utilised alternative methods of protection, including lead time advantage, secrecy, and increased complexity built into their designs.[75]

The Place of Design in Australian Intellectual Property Law

Watch

First, watch this short video where DesignByThem explain what registered designs mean to designers.

IP Australia identified in a recent study the reasons why those protect their designs with a registered design. The primary driver is to safeguard their revenue by preventing others from copying or avoiding others claiming rights over similar designs.[76] Other motivations included enhancing an organisation’s ability to attract and retain customers, boosting its image, and supporting the marketing of its products and services.[77]

Moreover, IP Australia put a price tag on the value of registering a design. They estimate that designs protected by design rights have a higher value than those that do not. A design protected with an Australian design right has an average value of $3.7 million compared to $678,227 for those which are not protected.[78] Designs protected with overseas design rights had an even greater average value at $5.8 million.[79]

To get a better picture of the landscape for design protection in Australia, we can turn to the Australian Designs Register. Currently, there are over 50,000 designs registered with IP Australia and nearly 10,000 are certified.[80] These figures are much lower than the number of trade marks and patents filed with IP Australia.[81]

To delve further into these figures, IP Australia produces an annual report on intellectual property filings each year.

Watch

Now, watch the following video that introduces the 2025 Australian Intellectual Property Report.

Looking back at the previous report (2024), annual applications for design rights in Australia grew to a record high of 8,776 applications, up by 11.5% on their level in 2022. Although in 2022, applications fell by 3.6% to 7,836 in 2022, following a record-breaking increase of 13.3% in 2021.[82] The growth was attributed to a 10.5% increase in applications filed by Chinese applicants.[83]

The following report (2025) shaw design applications reaching a record level in 2024, up by 8.9% on their level in 2023. Design registrations also reached a record high, up by 10.7%. This is best illustrated when compared to applications for other intellectual property rights (Figure 1).

Figure 1 – IP rights statistics 2024

Figure 2 illustrates the change in annual filings and the number of registrations and certifications. Last year, IP Australia saw an increase of 8.9% in design registrations compared to the previous year. Moreover, 1,474 of the design registrations were certified.

Figure 2 – Design applications, registrations and certifications in Australia, 2012 to 2024

(IP Australia CC-BY 4.0)

The demand for registered designs predominantly comes from overseas applicants (6,698 applications filed in 2024 up from 6,143 fled in the previosu year, a rise of 9%).[84] Australian design applications also increased from the previous year, with 2,885 applications filed in 2024 (an increase of 8.6%).[85]

Figure 3 – Resident and non-resident design applications, 2015 to 2024

(IP Australia CC-BY 4.0)

Figure 4 shows the annual number of design applications (%) filed with IP Australia between 2015 and 2024 based on their origin. The leading overseas countries filing for design rights were the US (US applicants were named on 1,940 applications), China (1,567), the United Kingdom (403), Hong Kong (338) and Switzerland (239).

Figure 4 – Leading countries of origin for design applications, 2024

(IP Australia CC-BY 4.0)

To understand what these designs were filed for, Figure 5 below presents the number of applications based on the Australian Design Classification Codes. In Australia, designs are classified using 32 product categories. These categories are listed in Appendix A and are discussed in more detail in Chapter 3. In 2024, 8.9% of all applications were designs for ‘transport’ designs.

Figure 5 – Top five design classes for volume of design filings in 2023

(IP Australia CC-BY 4.0)

According to the figure below, the top international applicant is Miss Amara, a rug producer, with 249 applications in 2024. The company originated in Australia but now operates internationally. Following was Apple Inc, in third place, and 2 Chinese technology producers.

In 2024, an individual designer came first, with Tatjana Petreska (from Victoria) filing 142 applications for articles of adornment (i.e., jewellery). Schneider Electric Australia (second), Phoenix Industries (third), and Systems IP (fourth) return to the list of lead domestic filers.

Figure 5 – Top domestic and international applicants for design rights in Australia

(IP Australia CC-BY 4.0)

The International Framework for Design Protection

Intellectual property laws are one of the most harmonised areas of law around the world. Efforts to harmonise the law resulted from numerous agreements and treaties agreed to by member states. Those international agreements and treaties that affect Australia’s design protection are described below.

Paris Convention

The Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property was signed in Paris, France, on 20 March 1883.[86] The Paris Convention is one of the very first intellectual property treaties. Australia has been a member of the Convention since 1925. The Paris Convention sets out minimum standards for protecting intellectual property rights. The provisions require Australia to grant the same protection for designs to nationals of other member countries as it does to its nationals.

In addition, the Convention provides for the right of priority. Applications filed with IP Australia from member states will have ‘priority’ over applications filed during the same period. In practice, applicants who file an initial design application in one of the countries that have signed the agreement (known as a Convention Country) have six months to file in Australia to be treated as if they were filed on the same day as the first application. The subsequent applications benefit from not being affected by any event in the interim — for example, the sale of a product bearing the design in Australia. Equally, an Australian designer could file an application with IP Australia and, within six months, file in member states to maintain the Australian filing date. These applications are commonly referred to as Convention applications.

Locarno Agreement

The Locarno Agreement Establishing an International Classification for Industrial Designs (Locarno Agreement, named after the Swiss town of Locarno) is an international treaty signed in 1968 and established a design classification system.[87] The agreement aims to provide a standardised system for the classification of designs, making it easier for anyone to register their designs and search for similar designs on national design databases (searching the Australian Designs Register is described in more detail in Chapter 6). The Locarno Classification system is based on a hierarchical system of 32 classes and further sub-classes, each representing a particular product type. The system is administered by a Committee of Experts and is empowered to make amendments or additions to the original list created in 1968.

The agreement has been adopted by over 90 countries around the world and is administered by the World Intellectual Property Organization (WIPO). Australia, however, is not a party to the Locarno Agreement. Despite this, IP Australia uses a classification system (called the Australian Designs Classification Codes) based on the Locarno Agreement to make searching the prior art base easier. This will be discussed in more detail in Chapter 3.

TRIPS Agreement

The Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights (or TRIPS Agreement) is between all World Trade Organisation (WTO) member states.[88] It sets the minimum standards for many forms of intellectual property, including designs. As a WTO member, Australia is a party to the TRIPS Agreement.

The agreement aims to provide a framework for protecting and enforcing IP rights in international trade and promote innovation and technology transfer. The TRIPS agreement requires WTO members to provide adequate and effective legal means to prevent the infringement of intellectual property rights and to provide fair and equitable procedures for enforcing these rights. It also allows for certain limited exceptions and flexibilities, such as for public health or in cases of national emergency.

The Articles setting out Member State requirements for the protection of designs are below.

Article 25

Requirements for Protection

1. Members shall provide for the protection of independently created industrial designs that are new or original. Members may provide that designs are not new or original if they do not significantly differ from known designs or combinations of known design features. Members may provide that such protection shall not extend to designs dictated essentially by technical or functional considerations.

2. Each Member shall ensure that requirements for securing protection for textile designs, in particular in regard to any cost, examination or publication, do not unreasonably impair the opportunity to seek and obtain such protection. Members shall be free to meet this obligation through industrial design law or through copyright law.

Article 26

Protection

1. The owner of a protected industrial design shall have the right to prevent third parties not having the owner’s consent from making, selling or importing articles bearing or embodying a design which is a copy, or substantially a copy, of the protected design, when such acts are undertaken for commercial purposes.

2. Members may provide limited exceptions to the protection of industrial designs, provided that such exceptions do not unreasonably conflict with the normal exploitation of protected industrial designs and do not unreasonably prejudice the legitimate interests of the owner of the protected design, taking account of the legitimate interests of third parties.

3. The duration of protection available shall amount to at least 10 years.

Hague Agreement

The Hague Agreement Concerning the International Registration of Industrial Designs (Hague Agreement is an international treaty that aims to simplify the process of registering designs in multiple countries through the creation of an international registration system (also known as the Hague System).[89] Administered by the World Intellectual Property Organisation, it provides a centralised system for registering designs. An applicant can apply to protect a design with a single office and then extend it to other member countries. Applications can be filed with the International Bureau of WIPO, either directly or through the intellectual property office of a Contracting Party. Most international applications are filed directly with the International Bureau using WIPO’s website’s electronic filing interface.

Watch

Watch the following video that explains what the Hague System is.

The agreement has been in effect since 1925 and covers 94 countries, including the European Union, the US, and China. The Hague Agreement allows designers to protect their designs in multiple countries without having to file separate applications with each country’s intellectual property office, saving time and money.

However, it is important to note that Australians cannot use the Hague System. Australia is currently not a contracting party. As a result, applications cannot be accepted under this system, and Australians are not automatically entitled to use it. Australia has agreed to make all reasonable efforts to join the Hague Agreement as part of a free trade agreement with the UK. The process allows time to consider legislative and system changes after entering into the free trade agreement.

- Oxford Dictionary (3rd edition, 2010). The use of the terms ‘art’ and ‘design’ can overlap, resulting in a blurring boundary between the two. The term ‘applied art’ can describe the design or decoration of functional objects so as to make them aesthetically pleasing, which has applications in the fields of industrial design, graphic design and fashion design. See Oxford Dictionary of Art (3rd edition, 2004) ‘applied art’. ↵

- Macquarie Dictionary (7th edition, 2017) ‘design’ (def 1) ↵

- Ibid (def 2). ↵

- Ibid (def 3). ↵

- See Michael Lewrick, Patrick Link and Larry Leifer, The Design Thinking Playbook (Wiley, 2018). ↵

- Charlotte Fiell and Peter Fiell, The Story of Design (Goodman Fiell, 2018) 9. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- William Lidwell, Kritina Holden and Jill Butler, Universal Principles of Design (Rockport Publishers, 2nd ed, 2010) 12 ('Universal Principles'). ↵

- A D Russell-Clarke, Copyright in Industrial Designs (Sweet & Maxwell 4th ed, 1968) 1. ↵

- IP Australia, 'Defining Design' (Research Report, IP Australia, 2020) ('Defining Design'). ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid 11. ↵

- The chair sold at auction for a record-breaking £2,434,500 (equivalent to AU$4.7 million). See ‘By The Numbers: Marc Newson’s Lockheed Lounge Chair’, Sotheby’s Institute of Art (Webpage, 20 January 2016) <https://www.sothebysinstitute.com/news-and-events/news/marc-newson-lockheed-lounge-chair/> ↵

- See more generally, Bella Martin and Bruce Hanington, Universal Methods of Design (Rockport Publishers, 2012). ↵

- Ibid 6. ↵

- Universal Principles (no 8) 12. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Design Act 2003 (Cth) s 5 (definition of ‘design’) ('2003 Act'). ↵

- Ibid s 7. ↵

- World Intellectual Property, 'The Changing Face of Innovation' (Research Report No 944E, IP Australia, 2011) 2. ↵

- See for example C Coville et al., ‘5 Everyday Things You Won’t Believe Are Copyrighted’, Cracked (Article, 16 October 2012) <http://www.cracked.com/article_20066_5-everyday-things-you-wont-believe-are-copyrighted.html> ↵

- Estelle Derclaye and Matthias Leistner, Intellectual Property Overlaps: A European Perspective (Hart, 2011) 1. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- An artistic view of design aligns with concepts and perceptions of copyright protection in artistic works and works of artistic craftsmanship. See Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) ss 10 (definition of ‘artistic work’), 77. ↵

- Mark Davidson, Ann Monotti and Leanne Wiseman, Australian Intellectual Property Law (Cambridge University Press, 2nd ed, 2012) 349 and Sam Ricketson, Thomson Reuters, Law of Intellectual Property: Copyright, Design and Confidential Information (online at 1 January 2023) [19.30]. ↵

- Defining Design (no 10) 8. ↵

- Productivity Commission, Intellectual Property Arrangements (Inquiry Report No 78, 23 September 2016) 339 ('Intellectual Property Arrangements'). ↵

- The Designs Act 2003 (Cth) replaced the Designs Act 1906 (Cth) and came into force on 17 June 2004. The Commonwealth’s legislative power in relation to intellectual property stems primarily from s 51(xviii) of the Constitution, permitting it to make laws with respect to ‘copyrights, patents of inventions and designs, and trade marks’. ↵

- 2003 Act (no 19) s 5 (definition of ‘design’). ↵

- Ibid s 7. ↵

- Ibid s 6. ↵

- Ibid s 7. ↵

- A drawing of a design, like that of the appearance of a smartphone may be protected as an original artistic work under copyright. However, the design becomes the subject of protection under the Designs Act when it has been applied to the product for manufacture. See Copyright Act 1968 (Cth) ss 74-77. ↵

- See Re Wolanski’s Registered Design (1953) 88 CLR 278, 279 and 2003 Act (no 19) s 5 (definition of ‘design’). ↵

- Australian Law Reform Commission, Designs (Report No 74, 1995) 2.4 ('Designs Report'). ↵

- 2003 Act (no 19) ss 13-14. ↵

- IP Australia, ‘What a Design Right Protects’, Designs Examiners’ Manual of Practice and Procedure (Web Page, 7 April 2022) <https://manuals.ipaustralia.gov.au/design/what-a-design-right-protects>. ↵

- 2003 Act (no 19) s 10. ↵

- Ibid s 15. ↵

- Intellectual Property Arrangements (no 29) 342, Advisory Council on Intellectual Property, Review of the Designs System (Final Report, March 2015), 19 ('Review of the Designs System'). ↵

- Sam Ricketson, ‘Towards a Rational Basis for the Protection of Industrial Design in Australia’ (1994) 5 Australian Intellectual Property Journal 193, 194 ('Protection of Industrial Design in Australia'). ↵

- Review of the Designs System (no 42). Also see Jani McCutcheon, ‘Too Many Stitches in Time? The Polo Lauren Case, Non-infringing Accessories and the Copyright/Design Overlap Defence’ (2009) 20 Australian Intellectual Property Journal 39, 52. ↵

- Intellectual Property Arrangements (no 29) 3. ↵

- Ibid iv. ↵

- See William Landes and Richard Posner, ‘Trademark Law: An Economic Perspective’ (1987) 30 Journal of Law and Economics 265-309. ↵

- See Industrial Property Advisory Committee, Patents, Innovation and Competition in Australia (Report, 1984) 11-18. ↵

- However, there can be some competing considerations when looking at the need for protection within copyright. See Stephen Breyer, ‘The Uneasy Case for Copyright: A Study of Copyright in Books, Photocopies and Computer Programs’ (1970) 84 Harvard Law Review 281. ↵

- Explanatory Memorandum, Designs Bill 2002 (Cth) 2. ↵

- Ibid ↵

- See William Fisher, ‘Theories of Intellectual Property’ in Stephen Munzer (ed), New Essays In the Legal and Political Theory of Property (Cambridge University Press, 2001) 168, 169-170 ('Legal and Political Theory of Property'). ↵

- Universal Declaration of Human Rights, GA Res 217A (III), UN GAOR, UN Doc A/810 (10 December 1948). ↵

- Legal and Political Theory of Property (no 52) 168-9. ↵

- Commonwealth of Australia, Australian Government Response to the Productivity Commission Inquiry into Intellectual Property Arrangements (Response, 25 August 2017) 2.1. ↵

- Defining Design (no 10) 7. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Designs Report (no 37) 2.13. ↵

- Defining Design (no 10) 8. ↵

- See Gil Appel, Barak Libai and Eitan Muller, O’n the monetary impact of fashion design piracy’ (2018) 35(4) International Journal of Research in Marketing 591. ↵

- These issues have been the predominant focus of IP Australia’s reform work on the registered designs system. See IP Australia, ‘Enhancing Australian Design Protection’ Consultations (Web Page, 13 August 2023) <https://consultation.ipaustralia.gov.au/policy/enhancing-australian-design-protection/> and, ‘Design Initiatives’, IP Australia (Web Page) < https://www.ipaustralia.gov.au/about-us/our-agency/our-research/design-initiatives> and Michael Campbell and Lana Helperin, ‘Redesigning Designs: The Future of Design Protection in Australia’ (2020) 121 Intellectual Property Forum 9, 13-15 ('The Future of Design Protection'). ↵

- Defining Design (no 10) 6. ↵

- Protection of Industrial Design in Australia (no 43) 193. ↵

- See Mitchell Adams, ‘Empirical Studies of Non-Traditional Signs in Australian Trade mark Law’ (PhD Thesis, Swinburne University of Technology, 2022) ↵

- See Emma Caine and Andrew Christie, ‘A Quantitative Analysis of Australian Intellectual Property Law and Policy-Making Since Federation’ (2015) 16(4) Australian Intellectual Property Journal 18. ↵

- Protection of Industrial Design in Australia (no 43) 196. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- James Lahore, ‘Current Problems and Future Prospects in Designs Law’ (Paper presented at the Intellectual Property Law: Trends and Tensions, Centre for Intellectual Property Studies, Queensland, 1992) 30. ↵

- The Future of Design Protection (no 62) 10. ↵

- Defining Design (no 10) 4. ↵

- See James Moultrie and Finbarr Livesey, ‘Measuring design investment in firms: Conceptual foundations and exploratory UK study’ (2014) 43(3) Research Policy 570. ↵

- Designs Report (no 37) 2.9. ↵

- IP Australia, 'Protecting Designs' (Research Report, IP Australia, 2020) 4. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid 21. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Data taken from ‘Australian Design Search’, IP Australia (Web Page, 1 December 2024). ↵

- See more generally, IP Australia, 'Australian IP Report 2025' (Research Report, IP Australia, 2025) ↵

- Ibid 62. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid 65. ↵

- Ibid 66. ↵

- Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property (20 March 1883); as revised at Brussels on 14 December 1900, at Washington on 2 June 1911, at The Hague on 6 November 1925, at London on 2 June 1934, at Lisbon on 31 October 1958 and at Stockholm on 14 July 1967, and as amended on 28 September 1979. See more information at ‘Paris Convention for the Protection of Industrial Property’, World Intellectual Property Organisation (Web Page) <https://www.wipo.int/treaties/en/ip/paris/> ↵

- LocarnoAgreementEstablishinganInternationalClassificationforIndustrialDesigns(Locarno,8October1968).See‘LocarnoAgreementEstablishinganInternationalClassificationforIndustrialDesigns’WorldIntellectualPropertyOrganisation(WebPage)<https://www.wipo.int/treaties/en/classification/locarno/>ocarnoAgreementEstablishinganInternationalClassificationforIndustrialDesigns(Locarno,8October1968).See‘LocarnoAgreementEstablishinganInternationalClassificationforIndustrialDesigns’WorldIntellectualPropertyOrganisation(WebPage)<https://www.wipo.int/treaties/en/classification/locarno/>World Intellectual Property OrganisationalClassificationforIndustrialDesigns(Locarno,8October1968).See‘LocarnoAgreementEstablishinganInternationalClassificationforIndustrialDesigns’WorldIntellectualPropertyOrganisation(WebPage)<https://www.wipo.int/treaties/en/classification/locarno/> ↵

- Agreement on Trade-Related Aspects of Intellectual Property Rights, 15 April 1994, Marrakesh Agreement Establishing the World Trade Organisation, Annex 1C, 1869 UNTS 299, 33 ILM 1197. ↵

- Hague Agreement Concerning the International Deposit of Industrial Designs (November 16, 1925); as revised London (2 June 1934), Monaco (18 November 1961) and Stockholm (14 July 1967). See ‘Hague Agreement Concerning the International Registration of Industrial Designs’, World Intellectual Property Organisation (Web Page) <https://www.wipo.int/treaties/en/registration/hague/> ↵