7 Ownership

Mitchell Adams

Contents

As mentioned in Chapter 3, different kinds of individuals may be entered on the Register as the registered design owner. A common understanding of the design process would be that the designer (the person who created the design) would be the initial owner. The designer would, therefore, fill out the application form to register the design with IP Australia. However, the Act sets out five categories of individuals who may be entitled to be registered as the registered owner of a design.[1]

Who is Entitled?

Section 13 identifies who is entitled to apply for registration, as no other person is entitled to apply for and obtain such registration. Section 14 then sets out who the registered owner is upon registration. At the point of application, it is important to correctly list entitled applicants on the application form. Disputes about who is listed as registered owners can lead to challenges in front of IP Australia or the Federal Court.[2] Such disputes can include how an application should proceed at the application stage if there is a disagreement between applicants,[3] changes in ownership before or after registration,[4] or where a non-applicant claims ownership.[5]

Read

DESIGNS ACT 2003 – SECT 13

Who is entitled to be registered as the registered owner of a design

(1) A person mentioned in any of the following paragraphs is entitled to be entered on the Register as the registered owner of a design that has not yet been registered:

(a) the person who created the design (the designer);

(b) if the designer created the design in the course of employment, or under a contract, with another person–the other person, unless the designer and the other person have agreed to the contrary;

(c) a person who derives title to the design from a person mentioned in paragraph (a) or (b), or by devolution by will or by operation of law;

(d) a person who would, on registration of the design, be entitled to have the exclusive rights in the design assigned to the person;

(e) the legal personal representative of a deceased person mentioned in paragraph (a), (b), (c) or (d).

(2) Despite subsection (1), a person is not entitled to be entered on the Register as the registered owner of a design that has not yet been registered if:

(a) the person has assigned all of the person’s rights in the design to another person; or

(b) the person’s rights in the design have devolved on another person by operation of law.

(3) To avoid doubt:

(a) more than one person may be entitled to be entered on the Register as the registered owner of a design; and

(b) unless the contrary intention appears, a reference to the registered owner of a registered design in this Act is a reference to each of the registered owners of the design.

(4) No person other than a person mentioned in paragraph (1)(a), (b), (c), (d) or (e) is entitled to be entered on the Register as the registered owner of a design that has not yet been registered.

The starting point is that the ‘designer’ is the first owner,[6] the one who created the design. Such a person has the primary entitlement to apply for registration. The paragraph refers to a ‘person’, which is taken to mean a ‘natural person.’[7] Of particular note, such a reference would limit the registration of computer-generated designs with the use of generative artificial intelligence.[8]

However, the provision does not say what it takes to ‘create’ the design. This was a similar position under the previous 1906 Act that referred to an ‘author’ of the design.[9] In 1985, Smithers J of the Federal Court provided the following explanation as it related to an ‘author’ of a design in Chris Ford Enterprises Pty Ltd v BH & JR Badenhop Pty Ltd: [10]

…authorship is in the person whose mind conceives the relevant shape, configuration, pattern or ornamentation applicable to the article in question and reduces it to visible form.

The Federal Court followed the same approach under the 2003 Act in LED Technologies Pty Ltd v Elecspress Pty Ltd.[11] Smithers J’s explanation sets out two elements that need to be satisfied for a person to create a design. First, the person conceives the design, either as the result of mental or intellectual processes and second, the person renders it in a visual representation (for example, drawing or painting). [12]

Section 13 (3)(a) makes it clear that more than one person may be entitled to be entered on the Register as the registered design owner. Unlike the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth), which makes references to joint authorship of creative work,[13] there are no equivalent references to ‘join designership’.[14] Therefore, there is no guidance under the Act about what each co-designer must contribute when creating a design. Despite this, contributions to the creation of a design can be relevant when determining who is entitled to apply for and obtain such registration.[15]

Paragraphs 13(1)(b)-(e) lists the other individuals who are entitled to register as the registered owners of the design. However, before a design is registered, any of these persons are barred from registering the design if they have assigned their rights in the design or the rights have devolved on another person by operation of law.[16]

Where a person creates a design during the course of employment, the employer is entitled to register it. Determining whether a design has been created during the course of employment would involve a factual inquiry.[17] Showing a person is employed is not enough; the creation of the design must be part of the employee’s duties, and it is something that they are reasonably expected to do.[18] Therefore, an employee creating designs in their spare time would not entitle an employer to register the designs.[19]

A party can also commission a design from an independent contractor. The section states that where the design is created ‘under a contract’ with another person, that other person is entitled to register the design. Furthermore, the paragraph permits the parties to agree to arrange a different outcome for employee and commission designs. Therefore, the employee or independent contractor may become entitled to apply with the employer or separately.

Other individuals may obtain the entitlement to apply for registration despite not originally creating or commissioning the design. Before a design is registered, they may derive the title from the designer or commissioner.[20] Such individuals may derive the title to the design through assignment, obtain it as a gift or through devolution by will or by operation of law (for example, bankruptcy or intestacy).[21]

A person can be entered on the Register where, upon registration, they would be entitled to an assignment of the design.[22] For example, a legal obligation can be created under a contract between the designer and a third party — stipulating that the designer assigns the design once it has been registered would create. A breach of such an obligation would give rise to a remedy of specific performance rather than damages.[23] Section 13(1)(d) permits such persons to register the design. Fiduciary or obligations of confidence may also create an equitable entitlement.[24]

Finally, a legal personal representative of a deceased person mentioned in paragraphs (a), (b), (c) or (d) is entitled to be registered as the registered owner of a design.[25] A ‘legal personal representative’ is further defined under s 5 to mean a person to whom: (a) probate of the will of the deceased person or (b) letters of administration of the estate of the deceased person; or (c) other like grant. Subparagraphs (a) and (b) are intended to cover legal forms used in Australia, while subparagraph (c) is intended to cover foreign grants.[26]

Ownership of the registered design

Section 14 clearly defines the ‘registered owner’ after the registration process. The starting point is that individuals listed in the Register as the registered owners, whether single or multiple persons, will be considered as such.[27]

The remaining provisions (s 14(2)-(4)) cover co-ownership of designs. Section 14(2) begins with the statement that co-owners are entitled to an equal, undivided share in the exclusive rights to the design. The remaining paragraphs set out the rules as to the respective rights of co-owners of a registered design,[28] all of which are subject to any contrary agreement between them.[29] Paragraph 14(3) deals with the third-party purchase of a product that embodies a design. The buyer and a person claiming through the buyer may deal with the product as if all the registered owners had sold it.

Read

DESIGNS ACT 2003 – SECT 14

Ownership of registered designs

(1) The registered owner of a registered design at a particular time is:

(a) the person who, at that time, is entered in the Register as the registered owner of the design; or

(b) if, at that time, there are 2 or more such persons–each of them.

(2) If there are 2 or more registered owners of a registered design:

(a) each of them is entitled to an equal, undivided share in the exclusive rights in that design; and

(b) subject to paragraph (c), each registered owner is entitled to exercise the exclusive rights in the design to the registered owner’s own benefit without accounting to the others; and

(c) none of them can grant a licence to exercise the exclusive rights in the design, or assign an interest in the design, without the consent of the others.

(3) If a product that embodies a registered design is sold by any of 2 or more registered owners of the design, the buyer, and a person claiming through the buyer, may deal with the product as if it had been sold by all the registered owners.

(4) Subsection (2) is subject to any contrary agreement between the registered owners of a registered design.

Assignment of a design

Ownership of a registered design can pass between different parties. The exclusive rights that a registered owner enjoys,[30] are personal property and can be assigned or devolved by will or by operation of law.[31] The owners may assign all or part of the registered owner’s interest in the design in writing.[32] After an assignment occurs, the registered owner (assignor) or the person who received the rights (assignee) may ask the Registrar to officially record the transfer of rights in the Register officially.[33] The Registrar will notify each registered owner of the request and record the assignment unless any other registered owner advises the Registrar that they do not consent to the assignment.[34]

Ownership Disputes

When seeking registration, it is crucial to correctly identify the owner entitled to register the design when filling out the application. Despite the simple online form, conflicts about ownership of a design can arise at the time of application or after registration. Ownership disputes can be complex and difficult to resolve. Disputes can emerge in the following situations:

- Between the joint applicants about whether or how to proceed with the design application.

- When a non-applicant claims ownership instead of the applicant(s) or as a joint applicant.

- When recording a change of ownership before registration.

IP Australia has identified typical situations where ownership disputes can emerge.[35]

Employees author a design in their own time

The employer is likely to be entitled to register the design if the design relates to something the employee is expected to do as part of their work duties.

However, if the employee’s duties do not involve suggesting or developing new designs, they are entitled to a design developed in their spare time – even if it relates to the employer’s business.

Company director authors a design in their own time

If a company director authors a design in their own time that is directly relevant to the business of the company, their obligations as a director may mean the design belongs to the company.[36]

Design application from an employee in their own name

An employee is normally not entitled to register in their own name a design they created at work. The employer is generally entitled to the design.

The question is whether the employee had the express consent of the employer to register the design in their own name. In particular, the employer’s failure to respond to requests for consent does not constitute consent.[37]

Design application from a former employee

These are cases where a former employee files design applications a few weeks or months after they leave a job. Their former employer believes that the employee authored those designs before leaving the job (in which case the designs would belong to the employer) but deliberately hid them. The person asserts that they created the designs after leaving the job. Given the potential for evidence to be deleted/destroyed, these situations often depend heavily on circumstantial evidence.

Unclear employment arrangement

Ownership disputes may arise where there is doubt as to whether an employee/employer arrangement is ‘real’. For example, the fact that prisoners received a weekly allowance from a prison authority did not mean that they were employees of the authority.[38]

Design created by a group of contributors

If all the contributors worked for the same employer, that employer was entitled to register the design. But if some worked for a different employer who was not named in the registration, the registered owner may not be entitled to the design.

Design authored by one person as part of a collaboration

Ownership of the design may be determined on the basis of the collaboration. In other words, if one person created the design in the sense that they actually drew it, but a team created the design in the sense that they collectively developed it, the team may be regarded as the design’s owner.[39]

Breach of confidentiality

If a design is disclosed in circumstances where implied confidentiality is breached, ownership of the design may be disputed.[40]

When can an ownership dispute occur?

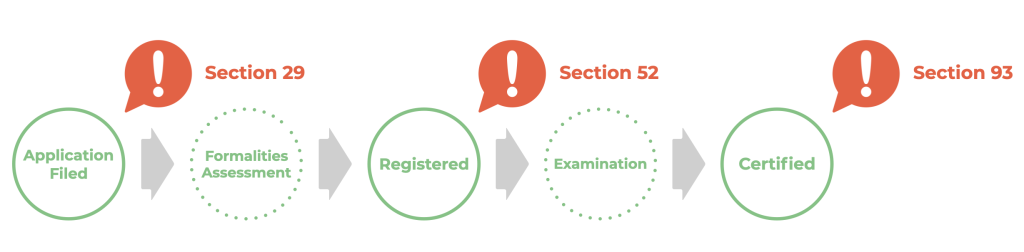

Ownership disputes can occur at any time during the lifecycle of a design registration. Overall, the types of disputes can include:

- Disagreement between joint applicants on whether or how an application should proceed.

- Disputes about recording a change of ownership before registration.

- Non-applicants claiming ownership after a design is registered or certified.

Under the Act, the Designs Office or a prescribed court can resolve disputes that arise during the lifecycle. The diagram below shows you which points in the lifecycle a dispute can emerge and which sections of the Act are relevant.

Whether and how an application should proceed

Joint applicants may disagree on how to proceed with an application. Although rare, one applicant can block another from moving forward. Specific disputes among joint applicants have arisen in patent cases — including, for example, when one applicant refuses to sign a document or requests that the application proceeds in their name only.[41]

Disputes between joint applicants about how a design application should proceed are dealt with under s 29. Read the section below.

The outcomes of these disputes can include deleting an applicant who deliberately blocks the application or requiring all parties to agree on all documents to be filed.[42]

Read

DESIGNS ACT 2003 – SECT 29

Disputes between applicants

(1) This section applies if a dispute arises between 2 or more persons in relation to whether, or in what manner, a design application should proceed.

(2) The Registrar may, on a request made in accordance with the regulations by any of the persons, make any determinations the Registrar thinks fit for either or both of the following purposes:

(a) enabling the application to specify which of those persons is an entitled person in relation to a design disclosed in the application;

(b) regulating the manner in which the application is to proceed.

(3) A person mentioned in subsection (1) or (2) must be:

(a) the applicant; or

(b) a person who asserts that the person is an entitled person in relation to a design disclosed in the application.

A non-applicant claims they have the right to apply

A non-applicant claiming entitlement to be a registered design owner may occur before or after a design is registered. The likely outcome sought by these individuals would be to add themselves as a new or additional applicant to a design. The non-applicant could make an application under sections 29 or 51. The result of the application would not be a new application, but rather a change to the existing application.[43]

If the design application has been registered or published, the Registrar will not make a determination under section 29. The ownership dispute will be handled under section 52 (discussed below). However, if an application has yet to be registered or published, a non-applicant may still suspect they are the entitled owner and make an application under section 29.

As discussed in Chapter 3, a design application is not open for public inspection until it is registered. Therefore, non-applicants may find it difficult to argue their claim to entitlement without seeing what is in the application or even knowing about it in the first place. If the non-applicant is aware, the parties can agree to exchange documents without involving the Registrar to help settle the dispute.[44] Otherwise, section 61 will restrict unpublished documents from being made available for inspection. In some situations, if a non-applicant makes an application under section 29, the Registrar may permit a section 29 application to convert to a section 51 proceeding.[45]

Change of ownership before registration

Once an application has been submitted, a change of ownership, such as an assignment of rights, could occur before it is registered. If this happens, it can be recorded under section 30 of the Act.

DESIGNS ACT 2003 – SECT 30

Persons may ask for design application to proceed in the person’s name

(1) A person may ask the Registrar to direct that a design application specify the person as:

(a) an applicant; or

(b) an entitled person in relation to a design disclosed in the application.

(2) The Registrar may give the direction if the person would, if the design were registered, be entitled under an assignment or agreement, or by operation of law, to:

(a) the registered design or an interest in it; or

(b) an undivided share in the registered design or in such an interest.

(3) If the Registrar gives the direction:

(a) the person is taken to be an applicant or an entitled person in relation to the design, as the case requires; and

(b) the application is taken to be amended accordingly.

(4) A request under subsection (1) must be in accordance with the regulations.

Although it can be rare,[46] disputes about the process of recording a change can occur. If there is a dispute about ownership before registration, the Registrar will address it under section 29. IP Australia has identified the main issues when assigning or transferring the title of a design that can lead to problems in recording changes, including:[47]

- errors in an assignment document.

- time-limited assignments and partial assignments.

- entitlement of a later registered owner.

- assignment by a co-owner.

Change of ownership before registration after lapsing

As discussed in Chapter 3, an application can lapse during the application process —that is when an applicant does not address a formalities notice. Despite this, a dispute between applicants about how to proceed with an application could still occur.[48] If an application has lapsed, IP Australia will only consider how the application is to proceed if there is an outstanding request to restore the application made pursuant to section 137.[49] The Registrar will decide whether to simultaneously consider the restoration with the ownership dispute after reviewing the facts of the case.[50]

Revocation on Grounds Relating to Entitled Persons

Ownership disputes are more likely to emerge once an application is registered and its contents are open for public inspection. Non-applicants may claim that they are entitled to register the design, either instead of the applicant or as joint applicants. Because the design is registered, it cannot be dealt with under section 29. Therefore, the non-applicant must request that the Registrar revoke the design. If entitlement is established, the registered design is revoked, and a written declaration is issued stating who was entitled to register the design when it was registered.[51] During court proceedings relating to a registered design, a court can also declare who was entitled to register the design.[52] The correct owner can then apply to register the design in their own name and retain the priority date of the initial application.[53]

Competing ownership claims of a registered design will go before the Registrar in a hearing to assess the claims. Under the Act, a third party can apply {form} under s 51 to revoke the registered design based on ownership entitlement. IP Australia will first assess the application, and if there is an arguable case, the registered design owners are given a copy of the request and asked if they will contest the claim.[54] Otherwise, the application will be dismissed.[55]

DESIGNS ACT 2003 – SECT 51

Revocation of registration on grounds relating to entitled persons

(1) A person may apply to the Registrar for revocation under section 52 of the registration of a design.

(2) An application under subsection (1) must:

(a) contain the information prescribed by the regulations; and

(b) be made in the manner prescribed by the regulations.

Sections 52 to 56 of the Act provide for resolving disputes on questions of who was entitled at the time of first registration of the design. This includes assessing the entitlement of each person entered in the Register as the registered owner at the time the design was first registered (called an ‘original registered owner’),[56] and whether other individuals were entitled to be registered owners.[57]

Subsection 52(2) contains the grounds for revocation. These grounds anticipate the typical situation in which a non-applicant to the original application claims they were entitled to register the design. A registered design will be revoked if, when the design was first registered, one or more of the original registered owners was not an entitled person, and another person or persons was entitled to register the design.[58] In addition, where each original registered owner was entitled at the time of registration, another person or persons was also entitled at that time.[59] The remaining provisions set out the process which follows. The Registrar has the right to decide how to handle requests for s 52 revocation in each case.[60] Read the section below. Interestingly, any third party can claim that another person or persons were entitled to the design when it was first registered, leading to revocation of the design.

Read

DESIGNS ACT 2003 – SECT 52

Procedures in relation to application

(1) This section applies if a person makes an application under section 51 for revocation of the registration of a design.

(2) If the Registrar is satisfied that:

(a) a person or persons were entitled persons at the time the design was first registered, and one or more of the original registered owners of the design was not an entitled person at that time; or

(b) each original registered owner of the design was an entitled person at the time when the design was first registered, but another person or persons were also entitled persons at that time;

the Registrar may make a written declaration specifying that a person whom the Registrar is satisfied was an entitled person at the time the design was first registered is an entitled person under this subsection.

(3) If the Registrar makes a declaration under subsection (2), the Registrar must:

(a) notify the relevant parties that the registration of the design is revoked; and

(b) make an entry in the Register under section 115.

(4) The Registrar must also publish a notice that satisfies the requirements prescribed by the regulations and that states that the registration of the design has been revoked and that the design is taken never to have been registered.

(5) The Registrar must not revoke the registration of a design under this section unless the Registrar has given each original registered owner a reasonable opportunity to be heard.

(6) The Registrar must not revoke the registration of a design under this section while relevant proceedings in relation to that design are pending.

(7) An appeal lies to the Federal Court or the Federal Circuit and Family Court of Australia (Division 2) against a decision of the Registrar under this section.

Revocation Process

An ownership challenge will likely lead to a hearing in front of the Registrar. IP Australia sets out the process for dealing with an application submitted under section 51.

The revocation process flowchart, Mitchell Adams (CC BY-NC)

Read

IP Australia’s overall process that follows is set out below.[61]

Request

Section 51 and reg 4.12 set out the requirements for requesting revocation under s 52.

The application must include a statement outlining the grounds for revocation under s 52. This statement should demonstrate to the Registrar that there may be a plausible case for revocation.

The applicant needs to be able to provide evidence to support their statement. For example, if their case is based on an alleged breach of a written agreement, they should be prepared to file a copy of the agreement later if and when the Registrar asks them to do so.

If the statement does not demonstrate a plausible case, the Registrar may ask the applicant to set out the grounds in greater detail. If the Registrar remains unconvinced that there is a case, but the applicant insists on pursuing it, the applicant will need to file all their supporting evidence.

If the Registrar determines that there is a plausible case – or if the applicant insists on pursuing it anyway – the owner will be notified and requested to answer within 1 month whether they intend to contest it.

If the owner does want to contest the application, they will need to file evidence supporting their entitlement to register the design.

If the owner does not contest the application, the Registrar may be able to deal with the matter ex parte – i.e. issue a declaration and revoke the design without requiring more evidence or a hearing.

Evidence

When the owner indicates that they will contest the request, the Registrar sets the process for submitting evidence. Typically, that will be:

- Each party has 2 months to file the original documents plus one copy. In some cases (see Requestabove) the applicant’s evidence may already be received.

- When each party has filed their evidence, a copy is sent to the other party.

- Each party then has 2 months to file their evidence (original plus one copy) in response.

- A copy of the evidence in response is sent to the other party.

- A hearing date is set for the matter.

The evidence is in the form of declarations. Regulation 11.26 sets out the requirements for a declaration.

Either party can ask for more time to prepare evidence or for permission to file further evidence. The Registrar has broad discretionary powers to deal with these requests on their merits. However, the Registrar strongly expects relevant evidence to be filed as promptly as possible and takes a very unfavourable view of those who withhold evidence until the last minute.

Production of documents

Under s 127(1)(c) the Registrar has the power to issue a notice requiring the production of a particular document or article that could be relevant to the proceedings. This notice can be:

- at the request of either party in the dispute.

- issued to either party or to a third party who is not involved in the proceedings.

This does not happen often. Points to note based on Registrar of Trade Marks / Commissioner of Patents practice are:

- Requests for the Registrar to issue a notice to produce should be made as early as possible in the proceedings.

- If there is any objection to the notice, the relevant point is whether there is a lawful excuse for not complying with it (s 134(2)). If necessary, the Registrar will conduct a hearing to determine whether there is a lawful excuse. This hearing is not about forcing production of the document; only a court can do this. If the outcome of the hearing is that there is no lawful excuse, the Registrar can draw an adverse inference from the refusal to comply.

- Where possible, the Registrar will encourage the parties to reach agreement between themselves about what will be produced. This avoids the costs and inconvenience of a formal determination.

Cross-examination

If one of the parties in the dispute requests it, the Registrar can summon a witness for cross-examination.

This happens rarely. Points to note based on Registrar of Trade Marks / Commissioner of Patents practice are:

- The Registrar will consider issuing a summons to appear:

- only if the cross-examination could be relevant to the proceedings.

- only to someone who has provided a

- only for that person to be cross-examined about that declaration (see reg 11.25) – not for the purpose of introducing substantially new evidence.

- If the Registrar does issue a summons, the party who requested it must:

- o make sure it is served promptly.

- o offer the person reasonable expenses to appear.

- If there is any objection to the summons, the relevant point is whether there is a lawful excuse for not complying with it (s 134(2)). The Registrar will not draw an adverse inference from the non-appearance of a witness without first being satisfied that they:

- o received the summons.

- o had a reasonable amount of time to arrange to attend the hearing.

- o received an enforceable offer (e.g. a non-refundable ticket) to pay reasonable expenses.

For an example of a contested summons to appear as a witness, see Airsense Technology Ltd v Vision Systems Ltd 62 IPR 409 and 62 IPR 413.

A declarant who attends a hearing might be called for cross-examination even if they have not received a written summons. (See Glass Block Constructions (Aust) Pty Ltd v Armourglass Australia Pty Ltd [2005] ADO 1 (6 January 2005)).

Hearing and decision

The hearing is under the full control of the Registrar’s delegate (the hearing officer). Typically, the applicant who initiated the s 52 matter will present their case first. The owner will then present their case and respond to the applicant’s case. Finally, the applicant will have a short opportunity to reply to the owner’s case.

Both the applicant and the owner have to demonstrate their entitlement to register the design. (See George Stack v Davies Shephard Pty Ltd and GSA Industries (Aust) Pty Ltd [1996] APO 1; (1996) AIPC 91-241; 34 IPR 117, a patents case that also applies to designs).

If the hearing finds a mismatch between the people who were entitled to register the design and those who actually registered it, the s 52 case is proved.

The Registrar should issue a written decision within 3 months of the hearing, unless the parties are given an opportunity to file more material. As part of the decision, the Registrar may order one of the parties to pay costs for the hearing.

The decision can be appealed to the Federal Court (s 52(7)), generally within 21 days (see the Federal Court Rules for details).

Revocation

To revoke the design, the Registrar:

- usually makes a written declaration stating who was entitled to register the design at the time when it was registered.

- notifies the relevant people that the registration is revoked.

- amends the Register and publishes a notice stating that the registration has been revoked.

The Registrar does not automatically issue a written declaration about entitlement to register. For examples, see Costa v G R and I E Daking Pty Ltd (1994) 29 IPR 241; and Allen Hardware Products Pty Ltd v Tclip Pty Ltd [2008] ADO 8 at 28–31.

Registration by the correct owner after revocation

After an ownership dispute ends with the design being revoked under s 52, the correct owner can apply to register the design in their own name.

To do this, they follow the normal application process. They also need to:

- advise the Registrar at the time of filing the application (or, at the latest, before registration) that they are claiming entitlement under s 55 to the revoked design, so that they can keep the same priority date and term of that design.

- submit a request for registration along with the application to prevent it from lapsing, as the priority date will usually be more than 6 months before the filing date.

If they later apply to renew this registration, the time period for renewal will start from the filing date of the original (revoked) registration.

Case examples

The following case examples demonstrate the application of the revocation provisions at the Australian Designs Office.

Read

Read Metroll Queensland Pty Ltd v Collymore [2008] ADO 8, where the Design Office considered the revocation of three designs for modular rainwater tanks. Metroll claimed entitlement to designs registered by their factory foreman Mark Collymore and his company, arguing they were created during the course of employment. The case provides crucial guidance on when designs created by employees belong to employers, adopting principles from patent law about inventions made during employment. It explores how employment duties and specific workplace directions affect design ownership, distinguishing between designs created independently versus those resulting from work tasks. The decision is particularly valuable for understanding how employment contracts and workplace relationships impact design rights, demonstrating that merely being employed by a company does not automatically give that company rights to all designs created by an employee.

Read

Read Allen Hardware Products Pty Ltd v Tclip Pty Ltd [2008] ADO 7, where the Design Office considered the revocation of eight designs for joiners used in construction. Tclip claimed joint entitlement to designs registered solely by Allen Hardware Products (AHP), arguing AHP had developed the designs using confidential information Tclip disclosed when seeking manufacturing assistance. The case provides crucial guidance on implied confidentiality in business relationships and joint design ownership. The hearing officer explored how design rights can arise from collaborative development, even when one party refines or modifies another’s initial concept. The decision is particularly notable for establishing that patent law principles about joint inventorship can apply to determining joint design creation. The hearing officer also provided detailed guidance on the practical implications of joint design ownership and the options available to disputing parties.

Read

Read John Michael Jarvie v Comtec Industries Pty Ltd [2018] ADO 5, where the Design Office considered the revocation of two designs for retaining wall components registered by Comtec Industries. John Jarvie claimed he was the sole designer and entitled person for both designs, despite not being listed as designer on either registration. The case provides crucial guidance on determining true designership and entitlement, particularly the principle that being a designer is a question of fact that cannot be altered by external factors like financial status. The hearing officer carefully analyzed evidence of the designs’ development history and the nature of relationships between the parties to determine who truly conceived the designs. The decision also explores the limits of the Registrar’s powers to alter design ownership after registration, highlighting that revocation may be the only available remedy even when the true designer is identified.

Read

Read Lyons Airconditioning Services (WA) Pty Ltd [2022] ADO 1, where the Design Office considered the revocation of a design for a caravan air pressurisation unit. Lyons Airconditioning claimed they were entitled to ownership of the design registered by Kedron Caravans, arguing Kedron had copied their existing ‘Carafan’ product after having access to it. The case provides important guidance on how design entitlement is determined, particularly when dealing with allegations of copying and claims of substantial similarity between designs. The hearing officer carefully analyzed the evidence of design development, access to prior products, and visual similarities/differences between the designs. The decision illustrates that simply having visual features similar to those of an existing product is not enough to establish entitlement – evidence must specifically demonstrate the creation of the registered design itself.

Read

Read Manuel Canestrini v Ilan El [2020] ADO 2, where the Design Office considered the revocation of two designs for the “Cannon Vase” filed by Ilan El. Manuel Canestrini, a former business partner of El, requested revocation, claiming he was the true designer and entitled person for both designs. The case provides valuable insights into how the Design Office determines design ownership and entitlement when faced with competing claims. In particular, the registered owner did not participate in the matter.

Through careful examination of the evidence, including email correspondence, design iterations, and public exhibitions, the hearing officer found Canestrini was the sole designer of one design but not the other. The decision demonstrates the importance of maintaining clear records of design development and highlights how different pieces of evidence are weighed when establishing who created a design.

Revocation after Certification

Ownership challenges can also occur after IP Australia has certified a design. Competing ownership claims of a certified design will need to go before a prescribed court to assess the claim.[62] The grounds for rectification are found in subsection 93(3) of the Act. Read the provision below.

DESIGNS ACT 2003 – SECT 93

Revocation of registration in other circumstances

(1) A person may apply to a prescribed court for an order revoking the registration of a design.

(2) An application under subsection (1) may be made only after the design has been examined under Chapter 5 and a certificate of examination has been issued.

(3) The grounds on which a court may revoke the registration of the design are:

(a) that the design is not a registrable design; or

(b) that one or more of the original registered owners was not an entitled person in relation to the design when the design was first registered; or

(c) that each of the original registered owners was an entitled person in relation to the design when the design was first registered, but another person or persons were entitled persons in relation to the design at that time; or

(d) that the registration of the design, or the certificate of examination, was obtained by fraud, false suggestion or misrepresentation; or

(e) that the design is a corresponding design to an artistic work, and copyright in the artistic work has ceased.

(3A) A court must not make an order under this section on the ground covered by paragraph (3)(b) or (c) unless the court is satisfied that, in all the circumstances, it is just and equitable to do so.

(4) In this section:

“original registered owner”, in relation to a design, means each person entered in the Register as the registered owner at the time the design was first registered.

- Designs Act 2003 (Cth) (‘2003 Act’) s 13. ↵

- Ibid ss 29 and 53. ↵

- Ibid s 29. ↵

- ss 29 and 30. ↵

- Ibid ss 52-56. ↵

- Ibid s 13(1)(a). ↵

- Australian Law Reform Commission, Designs (Report No 74, 1995) 134 (‘Designs 1995 Report’). ↵

- Cf Registered Designs Act 1949 (UK) s 2(4). ↵

- Designs Act 1906 (Cth) s 19(1) (‘1906 Act’). ↵

- (1985) 7 FCR 75; 4 IPR 485, 491. ↵

- (2008) 80 IPR 85, 96. The issue of the creation of a design was not pursued on appeal in Keller v LED Technologies Pty Ltd (2010) 185 FCR 449. ↵

- Sam Rickertson, Thomson Reuters, Law of Intellectual Property: Copyright, Design and Confidential Information (online at 1 October 2024) [22.05] (‘Law of Intellectual Property’). ↵

- ss 78-83. ↵

- Law of Intellectual Property (n 12) [22.05] ↵

- IP Australia, ‘Ownership Disputes: Typical Situations Where Ownership Disputes Arise’, Designs Examiners' Manual of Practice and Procedure (Web Page, 17 April 2024) <https://manuals.ipaustralia.gov.au/design/typical-situations-where-ownership-disputes-arise> citing Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation et al [1995] APO 16; 31 IPR 67; (1995) AIPC 91-171 (‘Typical Situations’). ↵

- 2003 Act (n 1) s 13(2). ↵

- See, eg, Metroll Queensland Pty Ltd v Mark Nicholas Collymore, Courier Pete Pty Ltd [2008] ADO 9. ↵

- See Courier Pete Pty Ltd v Metroll Queensland Pty Ltd (2010) 87 IPR 397; [2010] FCA 735. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- 2003 Act (no 1) s 13(1)(c). ↵

- Law of Intellectual Property (n 12) [22.15]. ↵

- 2003 Act (no 1) s 13(1)(d). ↵

- Law of Intellectual Property (n 12) [22.20]. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- 2003 Act (no 1) s 13(1)(e) ↵

- Law of Intellectual Property (n 12) [22.25]. ↵

- 2003 Act (no 1) s 14(1). ↵

- Ibid ss 14(2)(b)-(c). ↵

- Ibid s 14(4). ↵

- Ibid s 10(1). ↵

- Ibid s 10(2). ↵

- Ibid s 11(1). ↵

- Ibid s 114(1). ↵

- Ibid s 114(3). ↵

- Typical Situations (no 15). ↵

- Metroll Queensland Pty Ltd v Mark Nicholas Collymore, Courier Pete Pty Ltd [2008] ADO 9 and Spencer Industries v Collins [2003] FCA 542, 58 IPR 425. ↵

- Pancreas Technologies Pty Ltd v The State of Queensland acting through Queensland Health [2005] APO 1. ↵

- Eddie Kwan, John Pierre Le Sands and Paul N Van Draanen v The Queensland Corrective Services Commission and The Queensland Spastic Welfare League [1994] APO 53; (1994) AIPC 91-113; 31 IPR 25. ↵

- Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation et al [1995] APO 16; 31 IPR 67; (1995) AIPC 91-171. ↵

- Allen Hardware Products Pty Ltd v Tclip Pty Ltd [2008] ADO 8. ↵

- See Carroll and Harper, Re (1983) 1 IPR 537; Tribe & Ranken, Re Application by (1983) 1 IPR 561; and Milward-Bason and Burgess, Re Application By (1988) 11 IPR 567.. ↵

- IP Australia, ‘Ownership disputes: Disputes between joint applicants’, Designs Examiners' Manual of Practice and Procedure (Web Page 17 April 2024) <https://manuals.ipaustralia.gov.au/design/disputes-between-joint-applicants>. ↵

- IP Australia, ‘Ownership disputes: Disputes where a non-applicant claims ownership’, Designs Examiners' Manual of Practice and Procedure (Web Page 17 April 2024) <https://manuals.ipaustralia.gov.au/design/disputes-where-a-non-applicant-claims-ownership>. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- See Dennis Gravolin and Trailer Vision Pty Ltd v Locmac Holdings Pty Ltd as trustee for Locmac Trust [2007] ADO 7. In this case, confidentiality requirements mandated that such disclosure should not be made to a person in a position to obtain technical advantage from that disclosure. The applicant was self-represented, and allowing a legal representative to view the documents was not possible in this situation. ↵

- IP Australia, ‘Ownership disputes: Disputes about recording a change of ownership before registration’, Designs Examiners' Manual of Practice and Procedure (Web Page 17 April 2024) <https://manuals.ipaustralia.gov.au/design/disputes-about-recording-a-change-of-ownership-before-registration>. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- IP Australia, ‘Ownership disputes: Disputes where some designs have been registered or published’, Designs Examiners' Manual of Practice and Procedure(Web Page 17 April 2024) <https://manuals.ipaustralia.gov.au/design/disputes-where-some-designs-have-been-registered-or-published> (‘Disputes where some designs have been registered or published’). ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- 2003 Act (no 1) s 54; see also Costa v G R and I E Daking Pty Ltd (1994) 29 IPR 241 and Allen Hardware Products Pty Ltd v Tclip Pty Ltd [2008] ADO 8 [28]–[31]. ↵

- s 53 ↵

- 2003 Act (no 1) s 55 and John Michael Jarvie v Comtec Industries Pty Ltd [2018] ADO 5. ↵

- Disputes where some designs have been registered or published (no 48) ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- 2003 Act (no 1) s 56. ↵

- Ibid s 52(2). ↵

- Ibid s 52(2)(a). ↵

- Ibid s 52(2)(b). ↵

- See Designs Regulations 2004 (Cth) reg 11.24. ↵

- IP Australia, ‘Ownership disputes: Revocation after an ownership dispute’, Designs Examiners' Manual of Practice and Procedure (Web Page 17 April 2024) <https://manuals.ipaustralia.gov.au/design/revocation-after-an-ownership-dispute >. ↵

- 2003 Act (no 1) s 93. ↵