Chapter 6: Navigating feedback

Liam Frost-Camilleri

Learning Objectives

- Recognise the purpose of university-level feedback.

- Identify emotional responses to feedback and implement strategies to regulate those emotions.

- Apply techniques to effectively understand and act on feedback to improve academic performance.

- Distinguish between poor and effective feedback.

- Develop constructive feedback for peers, demonstrating clarity, balance, and actionable suggestions.

Perhaps the steepest learning curve when you are starting university is navigating the feedback you receive from lecturers and tutors. You may have started your classes well, your attendance might be high, you may have read the readings and articles, begun to forge friendships, and started to understand your subject areas and their backgrounds. However, the feedback you receive may be difficult for you to read and accept. This is because university feedback is targeted at your performance and trying to push you beyond your current skill levels. Generally, university feedback on assessments may point out a couple of things you have done well, but will spend much of the time highlighting areas in need of improvement. This focus on improvement is why many student struggle when they first read their feedback.

6.1 Dealing with emotions when receiving feedback

Feedback is an area that is quite well-researched in secondary and primary schools, but not as much at university level. Most researchers tend to focus on the different perspectives of students and lecturers (Henderson et al., 2019). Nevertheless, there is no doubt that feedback significantly impacts a student’s ability to develop and grow (Ahea et al., 2016). There are some terrific initiatives concerning feedback, with researchers like Carless and Boud (2018) endorsing positive feedback methods that develop feedback literacy and provide opportunities for lecturers to create a clear and open dialogue with their students about their growth.

Aside from discussing ‘readiness to receive feedback’, there is little research on the emotional toll feedback takes on students. This chapter discusses practical ways to deal with feedback and highlights the importance of emotional regulation as you navigate this rollercoaster. However, it could be worth reviewing Chapter 9 if you are feeling anxious and overwhelmed by this content.

When reading and trying to understand your feedback remember that it is not about you as a person. It is 100% about your work and only your work. While it would be nice for lecturers to spend time praising the effort you have put in, most will focus on enhancing your understanding or clarifying aspects of the content. In reality, institutes are divided as to whether praise should play much of a role in giving feedback (Morris et al., 2021). This is because most lecturers offer feedback to simply clarify understanding, not to praise or even point out what was done well. Lecturers who conduct research experience rejection of their articles and presentation ideas, which can be demoralising, but speaks to the culture of feedback and growth that is prevalent in academia.

When receiving feedback for the first time there is one important rule to follow: Do not email or message your lecturers for at least 24 hours after receiving your feedback. Giving yourself 24 hours allows you to emotionally regulate and better understand your feedback. You could feel a simple line or question written by a lecturer quite deeply, and this can be difficult to process, so giving yourself time is crucial. Once you feel calm, you can either accept the feedback or question it if it does not make sense to you.

Lecturers do not give feedback to belittle, they give feedback to help you grow as a learner. However, that does not mean you have to like it. It is important not to ‘stonewall’ your feedback and pretend it does not bother you. If you put effort into an assessment and did not achieve the score you felt you deserved, you have every right to feel angry, disappointed, disillusioned, anxious, sad, or any other combination of emotions. The important thing is to give yourself enough time to feel and process the emotion. To help process your emotions, consider the following strategies:

Seek understanding. Think about what is causing you to have an emotional reaction to the feedback. Is it the effort that you put in? Is it the idea that you might not be good enough for university?[1] Are you worried about letting someone down (including yourself)? Are you angry that you did not understand the topic as well as you thought? Or are you simply afraid of failure? These are a few possibilities, but understanding why you feel the way you do helps you to process it.

Be careful of self-criticism and rumination. There is no situation where beating yourself up will help. Your lecturer does not ‘hate you’ and your feedback is not because you are ‘stupid’, you just missed the mark this time. Negative self-talk will not help process your emotions; it will simply make you feel worse. It might be worth reviewing Chapter 2 on the concept of a growth mindset and the section on self-efficacy if you are struggling with feeling good about your feedback.

Emotional regulation. Regulating your emotions is different for everyone. Some people listen to music, others need to talk about how they feel with someone they trust. Energetic people prefer to run or swim while others watch a movie or make a comforting meal. Mindfulness is commonly used to calm down, but if this is not your thing, consider what makes you feel centred or calm. What activities help you ‘reset’?[2] Experiment and keep a record of what helps, so you can implement these strategies when things become emotionally difficult.

Reflect on your assessment. Once you have started to emotionally regulate, reflect on your assessment, and think about why you received the grade you did. What did you miss in the criteria and what is the feedback from the lecturer? What parts do you not understand and where can you grow and develop? Plan how you might address these points in future assessments.

Seek support. Consider who you can speak to. You might discuss your feedback with your peers to hear their insights, especially since they are enrolled in the same course or units and would have received feedback at the same time. Additionally, you can speak to learning advisers at the university, counsellors, or your family, friends, or even your cat or dog. While your pet might not respond, sometimes saying how you feel out loud will help you to process the situation. The important aspect of seeking support is finding someone you trust.

Positive reframing. Reframing the experience as positive can be empowering. Understanding the feedback gives you a chance to develop your skills further and is a terrific way to progress at university. Positive reframing can also help prevent withdrawing behaviours such as avoiding classes or disengaging from the content. It is a difficult step and is explained in detail in Chapter 2 concerning developing a growth mindset, but it helps you to navigate your feedback during your university journey.

That said, poor feedback does exist, and it is important to know the difference. If you feel your grade is unjustified, or the feedback is insufficient, the next step is to be clear about the kind of feedback you feel you deserved or what would have been more helpful. Simply telling your lecturer that their feedback “does not make sense” generally elicits the response “What don’t you understand?”, which is perhaps a fair point. If you cannot answer this question, the conversation may simply end. The first step in determining if your feedback is good or poor is understanding the criteria.

Using a piece of feedback that you have received in the past (you may choose something from secondary school if it was particularly upsetting), write a reflection about how you feel. Do not worry about correct punctuation or making the piece easily read. The point of this exercise is to help you explore how you feel. Give yourself a few minutes then read over your work to answer the following questions.

- What can you learn about who you are from this reflection?

- What does this reflection tell you about what triggers you when receiving feedback?

- Does this reflection offer any clues to strategies that might help you process your emotions?

6.2 Understanding criteria

It is crucial to understand how important criteria are when being assessed at university. Criteria are used to grade your assessments, provide feedback on how you can improve and will always be provided with the assessment details. They are almost always written to reflect the most important learnings of the course or unit, which means the more you understand the content, the better you will generally perform in assessments. More importantly, the criteria guides your assessor when grading your work. So, if your piece is beautifully written but fails to answer the assessment question, you should prepare yourself for a lower mark.

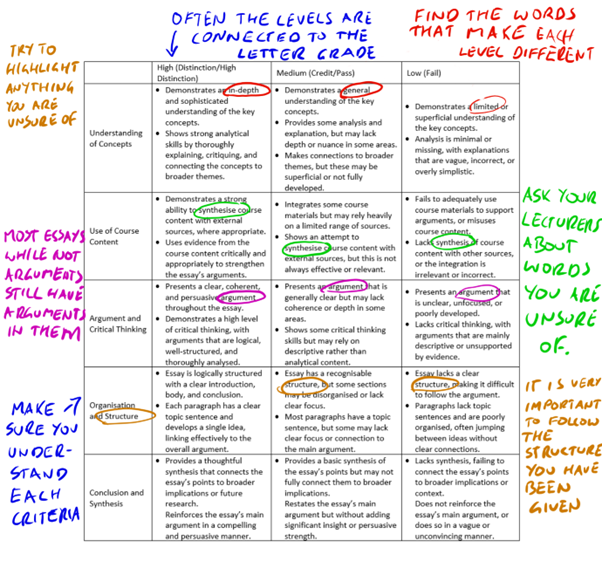

Sometimes, you will receive a set of marking criteria without a high, medium, or low rating or accompanying letter grade. This can depend on the marking tools prevalent in your chosen discipline. The following is an example of a common way to present criteria, called a rubric. Rubrics are tools for communicating, discussing, and marking assessments. Typically, rubrics have high, medium, and low columns, but they can come in a variety of formats. In any case, it is always worth discussing the criteria with your lecturer if you are unsure of anything. The following is a fairly generic rubric commonly used for assessments.

| High (Distinction/High Distinction) | Medium (Credit/Pass) | Low (Fail) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Understanding of Concepts | • Demonstrates an in-depth and sophisticated understanding of the key concepts. • Shows strong analytical skills by thoroughly explaining, critiquing, and connecting the concepts to broader themes. |

• Provides some analysis and explanation, but may lack depth or nuance in some areas. • Makes connections to broader themes, but these may be superficial or not fully developed. |

• Demonstrates a limited or superficial understanding of the key concepts. • Analysis is minimal or missing, with explanations that are vague, incorrect, or overly simplistic. |

| Use of Course Content | • Demonstrates a strong ability to synthesise course content with external sources, where appropriate. • Uses evidence from the course content critically and appropriately to strengthen the essay’s arguments. |

• Integrates some course materials but may rely heavily on a limited range of sources. • Shows an attempt to synthesise course content with external sources, but this is not always effective or relevant. |

• Fails to adequately use course material to support arguments, or misuses course content. • Lacks synthesis of course content with other sources, or the integration is relevant or incorrect. |

| Argument and Critical Thinking | • Presents a clear, coherent, and persuasive argument throughout the essay. • Demonstrates a high level of critical thinking, with arguments that are logical, well structured, and thoroughly analysed. |

• Presents an argument that is generally clear but may lack coherence or depth in some areas. • Show some critical thinking skills but may rely on descriptive rather than analytical content. |

• Presents an argument that is unclear, unfocused, or poorly developed. • Lacks critical thinking with arguments that are mainly descriptive or unsupported by evidence. |

| Organisation and Structure | • Essay is logically structured with a clear introduction, body, and conclusion. • Each paragraph has a clear topic sentence and develops a single idea, linking effectively to the overall argument. |

• Essay has a recognisable structure, but some sections may be disorganised or lack clear focus. • Most paragraphs have a topic sentence, but some may likely focus or connection to the main argument. |

• Essay lacks a clear structure, making it difficult to follow the argument. • Paragraphs lack a topic sentence and are poorly organised, often jumping between ideas without clear connections. |

| Conclusion and Synthesis | • Provides a thoughtful synthesis that connects the essay’s points to broader implications or future research. Reinforces the essay’s main argument in a compelling and persuasive manner. | • Provides a basic synthesis of the essay’s points but may not fully connect them to the broader implications. Restates the essay’s main argument without adding significant insight or persuasive strength. | • Lacks synthesis, failing to connect the essay’s points to broader implications or context. Does not reinforce the essay’s main argument, or does so in a vague or unconvincing manner. |

Have a read of these criteria and think about what the assessment is trying to get you to focus on. You may even wish to make a few notes on what you can see in each of the criteria, as follows:

The focus of this rubric is reasonably straightforward. There is an emphasis on presenting an argument, an understanding of the course or unit and the concepts discussed in class, and an ability to critically think and synthesise your ideas. While correct grammar and accuracy in your writing are important for fulfilling the criteria, they are not criteria that you are graded on here. This is a common misconception for students; you may write a fantastic essay that discusses the course or unit content but fail to use an argumentative structure, impacting your ability to score highly on the criteria ‘Argument and Critical Thinking’ and ‘Organisation and Structure’. While answering the question is crucial, it is also extremely important to be aware of what else you need to consider when constructing your assessment.

If you have considered the criteria and still believe your assessment addresses it quite well, then it is time to consider what makes the feedback poor, and what you might be able to do about it.

Choose an assessment that you have to complete and find the assessment’s criteria. Annotate these criteria and create a series of questions related to what you do not understand well.

- What do you notice about the criteria?

- What are the criteria trying to assess?

- What do you need to know more about to respond to the criteria appropriately?

6.3 Recognising and addressing poor feedback

Good feedback will usually start with something you have done well or that you have made a solid start. Then the marker will identify key things you need to do to improve your work so you know exactly what you need to do next. The feedback will be explicitly linked to the marking criteria or rubric. Poor feedback tends to focus on things that are not present in the criteria. All feedback should be tied to the course or unit content and the skills required for the assessment task. If you receive feedback contrary to this, then it is best to discuss it with your lecturer or assessor. However, it is important to note that while ‘inclusion of citations’ is not written on many rubrics, it is a general expectation that needs to be followed. The same could be said for using emotionally neutral language.

Importantly, in some instances, your assessor might not be your class lecturer. This is quite common for universities. In fact, many institutes opt to have different lecturers mark your work to avoid potential biases.

It is best to have a conversation about your assessment outside of classes. Feel free to talk to your lecturer during class, but try to lead with, “I wonder if we can have a conversation about my feedback on my last assessment?”. You can then find a mutual time to meet and discuss it.

When you meet with your lecturer, try to explain which parts of the criteria you felt your assessment fulfilled well (it may be helpful to bring a copy of your work and highlight relevant sections). This conversation is not about your disappointment, how hard you worked on your assessment, or the grades that other people in the class received. It is about the quality of the work that you submitted and whether it meets the criteria.

Most lecturers are happy to discuss their feedback and some also enjoy the challenge of improving how they mark. You may inadvertently help them become better at their job. If after this conversation you still feel uncertain about your feedback and wish to take it further, you can speak to a course coordinator or email the Dean (or equivalent) directly. The Dean or course coordinator may ask for the assessment to be marked by another academic to see if they agree.[3] A conversation then follows. This is quite a lengthy process, and it is always advisable to try to resolve the situation with the lecturer first, but it is important to know what your options are.

6.4 Providing feedback

As a student at university, you may be asked to provide feedback to your peers. Since most courses or units are connected to occupations, your ability to understand what ‘good practice’ looks like is an important skill that universities are responsible for developing.

When giving feedback, aim to be as clear as possible. Try not to confuse clarity with a lack of complexity. Your feedback can be complex, but it needs to be concise and to the point. You are aiming for your feedback to be easily understood.

Another important element of giving feedback is to be balanced. This does not mean you need to give a compliment sandwich[4] or something similar, it just means you should aim to give feedback that is measured and not exaggerated or emotional. Some students like to use metaphors in their feedback, but this not only impacts clarity, it can provoke an unwanted emotional response. Telling a peer that their voice in their presentation sounded like a “squeaking toy” may be taken quite harshly.

Lastly, ensure that the feedback you give is constructive. Constructive feedback offers an alternative or suggests something for the student to focus on. For instance, you might tell a peer that the speed of their presentation was too fast and that it might help the audience understand the topic better if they slowed down. You may also tell a peer that their reflection focused on what they did rather than on what they might do next. Useful and actionable constructive feedback is the aim here.

As you can see, feedback can be quite an emotional process. It is important to discuss your feedback and allow yourself to feel emotional about it while finding time to process how you feel.

6.5 Key strategies from this chapter

- Regulate your emotions: Giving yourself time to understand your emotions is an effective way to help regulate when receiving feedback.

- Reframe your feedback: Understand that feedback is an opportunity for growth and is about your work, not about you as a person.

- Seek to understand the criteria: Ensure that you have thoroughly read the criteria of your assessments to ensure your work meets the lecturer’s expectations.

- Identify poor feedback: Good feedback is linked to assessment criteria and focuses on improvement. If feedback is vague or not connected to the criteria, seek clarification.

- Provide effective feedback to your peers: Be clear, concise, constructive, and balanced in your feedback to your peers to practice giving effective feedback to others.

6.6 Chapter summary

In this chapter, we have:

- discussed how university feedback is primarily constructive and focuses on areas for improvement rather than only on praise, differing significantly from feedback at earlier educational levels.

- discussed emotional regulation and its role when receiving feedback.

- understood that assessment criteria are crucial when interpreting feedback.

- understood that poor feedback may exist, but recognising it requires a solid understanding of the criteria.

- examined how providing feedback to peers is an important skill at university, and it should be clear, balanced, and constructive to help others grow in their learning, and recognise good practice in your chosen discipline area.

6.7 Reflection questions

- How do you usually react emotionally when receiving feedback? What strategies could you use to regulate these emotions more effectively?

- Think of a recent piece of feedback you received. How did it align with the criteria for the assessment? Were there any discrepancies between your understanding of the task and the feedback?

- What is common in your feedback from your teachers? Are they all saying the same thing? How might you gain more clarity on this piece of feedback?

- Why is it important to separate personal feelings from the content of feedback? How can this improve your academic growth?

- In what ways can you improve the clarity of the feedback you provide to your peers?

- How can understanding the course or unit criteria in detail help you improve your future assignments?

References

Ahea, M. M. A. B., Ahea, M. R. K., & Rahman, I. (2016). The value and effectiveness of feedback in improving students’ learning and professionalizing teaching in higher education. Journal of Education and Practice, 7(16), 38-41.

Carless, D., & Boud, D. (2018). The development of student feedback literacy: enabling uptake of feedback. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 43(8), 1315-1325. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2018.1463354

Henderson, M., Ryan, T., & Phillips, M. (2019). The challenges of feedback in higher education. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 44(8), 1237-1252. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2019.1599815

- Just a side note: this is never the case. Every university has a screening process to ensure they do not enrol you in a course that is unsuitable for you. ↵

- When I ask students how they regulate emotions, and they are unsure, they often reply with “sleep”. While sleep is restful, it does not help us to regulate or process emotions. More exploration is needed if this is your response. Mindfulness, meditation, physical activity, journaling or breathing exercises are all far more beneficial when trying to regulate emotions. ↵

- Most universities will automatically cross-mark fail grades. Cross-marking is when a second assessor reviews a failed response to determine if they agree with the original grade. Some universities even cross-mark their High Distinction grades for a similar reason. ↵

- A compliment sandwich is feedback that has three parts. Something positive, some constructive criticism and then something else positive. The positive comments are the ‘bread’ and the constructive criticism is the ‘sandwich filling’. ↵