Chapter 5: Approaching university tasks

Liam Frost-Camilleri

Learning Objectives

- Examine how to approach university tasks.

- Understand the importance of planning strategy.

- Follow assessment instructions carefully.

- Manage the writing process by addressing common writing issues and barriers.

- Apply academic writing conventions such as register, clarity, objectivity and correct citation practices.

Learners find completing university writing tasks a difficult process for different reasons. Some students find it challenging to start a task, having a real aversion to a blank page. Others really enjoy the reading process but struggle with writing. The key to approaching university assessment tasks is understanding your struggles and how to cater for them. It is important to normalise feeling frustrated or unsure of what you are doing when approaching these tasks. Learning is an uncomfortable journey, and you have not done this before. Additionally, many of the tasks you will complete will be open-ended, requiring you to become a little more creative in the way you approach them.

All academics will advise you to start your assessments early. While this might not be how you normally operate, there are a few things you can do to develop the practice. First, try to simply think about and discuss the assessment well before starting it. Research has shown that understanding the task by discussing it with a variety of people (including your peers, lecturers, and wider support networks) can help you better navigate it (Hawe et al., 2019). Starting this process early will help to lower anxiety and give you time to revise your work. Consider some of the barriers you might have to starting this process early and try to address them. Additionally, giving yourself an earlier deadline of a week or a day before the assessment is due will ensure that you have time to spare if things go wrong.

Like all chapters in this book, you may find some strategies helpful and others not. This chapter highlights ways to approach university tasks that are helpful practices for most students. The chapter ends with some specific points concerning writing, and the advice you will read will be more suited towards addressing essay-style assessments. Courses and units, particularly in enabling education, will often include a wide range of different tasks such as case studies, laboratory work, field assessments, presentations, creative outputs, collaborative assessments, or even work-integrated learning. As all assessment styles are beyond the scope of this book, this chapter tries to provide general advice around planning and writing that could be used for most university assessments and tasks.

5.1 Before getting started

The first step when approaching university assessments is ensuring that you have everything you need to complete the task. This includes access to a computer, programs like Microsoft Word, a PDF reader, and the library’s research database. Make sure you have all course or unit resources including readings, lecture recordings, PowerPoints, and any additional notes. These resources need to be readily accessible before you can begin any preparation work. Next, ask your lecturers for examples of previous student work. Exemplars are fantastic resources when trying to get your head around how to do the task (Hawe et al., 2019). Lastly, do not be afraid to ask clarifying questions of your lecturers or tutors, even if you think they are ‘stupid questions’. You need to have a clear understanding of what is expected of you before you start planning. The research tells us that most students find it difficult to navigate academic writing conventions in their first year (Christie et al., 2014), so asking specific questions about what the writing should look like is an important step. Be aware that you might find some inconsistencies in writing expectations between courses or units (Wingate, 2006; Hassel & Ridout, 2018). Try to trust that you will eventually understand the nuances of writing expectations and that this will lead to a better understanding of academic reading, writing and critical thinking skills (Christie et al., 2014).

5.2 Visual planners

The importance of effective planning cannot be understated. Beginning assessments without sufficient planning can lead to overlooking important assessment requirements, going on irrelevant tangents, or disastrously having to start your assessment over again when you realise that it fails to answer the question or address the topic. Be aware of the type of planning that might assist you. You may simply find reviewing your notes, the readings, and the course content to be sufficient, but many students who are approaching a university assessment for the first time find visual planners to be especially helpful.

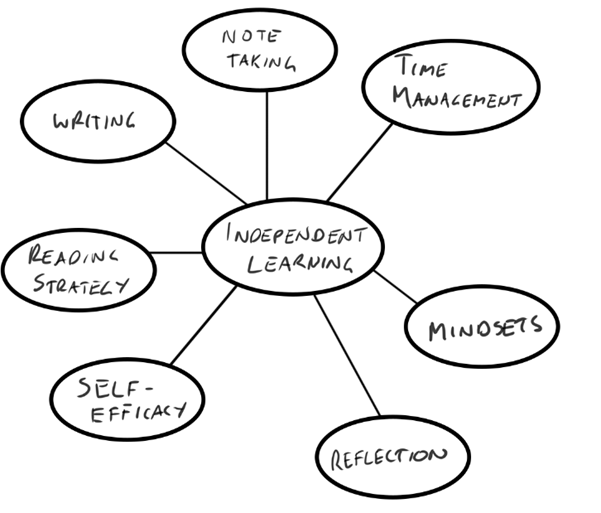

Perhaps the most common visual planner is a mind map. Mind maps are diagrams that you can use to connect concepts or ideas. It is sometimes helpful to write on the connections that you have made to help you explore your understanding. Putting the essay question or topic in the centre of your mind map and surrounding it with your thinking can help you visualise your assessment structure.

While creating a mind map is a terrific start to planning your assessment response, it is advisable for you to reflect on what you are trying to achieve in your planning. Think about the following questions before you start your visual planner:

- How can I organise the mind map?

- What are the relationships between these ideas and how can I record them?

- Do I understand every concept of the task? Do I need to go back to my notes and ask some questions?

- What question or questions am I trying to answer in this task?

- How can I rephrase the wording of the task to help my understanding?

- Do I have sources or evidence from the academic literature to support my main points or topics? If not, where are the gaps?

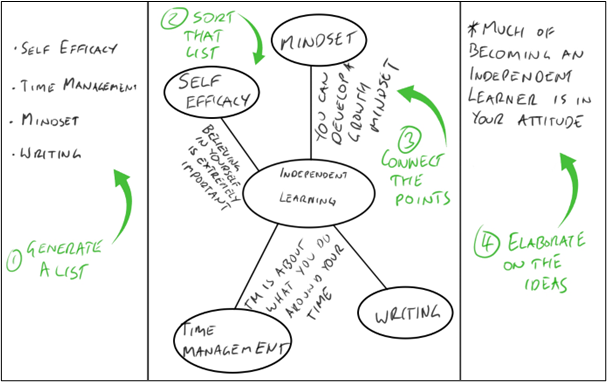

The Generate-Sort-Connect-Elaborate Thinking Routine is a very sophisticated mind-mapping tool developed by Senior Research Associate Ron Ritchhart. It is essentially a method of organising your thoughts and understanding into a mind-mapping tool. Here is a link to the tool and a template to use https://www.sadlier.com/school/ela-blog/how-to-use-generate-sort-connect-elaborate-concept-maps-visible-thinking-routine. For essay planning in particular the Generate-Sort-Connect-Elaborate Thinking Routine is a great way of visualising possible essay or report elements and ideas. Additionally, it can be beneficial to slightly change some of the elements of the Routine. For instance, when you connect the different elements in your mind map, think about why you are making the connections. A little elaboration or citation on the connection can aid clarity and strengthen your argument.

The key point for any visual planning tool is to experiment with how they can be used to assist you in your planning. Everything you do when planning should help shape and support your response to the assessment task.

Learning Activity 5.1 Generate, Sort, Connect, Elaborate [PDF]

Choose a question from the list below to create a Generate, Sort, Connect, Elaborate routine with.

- What does it mean to be an independent learner?

- How can self-efficacy be developed?

- How can we become more comfortable with productive struggle?

- How can reading strategy be developed?

- What important aspects are there when taking notes?

5.3 Following the instructions

Many university tasks stipulate precisely how you need to respond. There is a generally expected standard at most institutions: The assessment must be 1.5 or double spaced; the name of the task and unit needs to be placed in the header along with your name and student number; page numbers must appear on the footer; and there will even be a stipulation on the font and font size you must use. For this reason, it is essential that you read and reread the assessment instructions.

Most tasks have a leniency of 10% either way for their word counts. Meaning, if you were expected to write 1000 words for a task, you could write anywhere between 900 to 1100 words and not be penalised. If you go over the word count, some lecturers may refuse to mark your assessment. If you are under the word count it is likely that you have not explained your assessment in enough detail. Unlike high school, writing more words than was required is not desirable. In fact, an important skill in writing university assessments is being able to concisely communicate your points. It is also important that you do not include elements that were not asked for specifically. If the task does not ask for a title page, then do not include one. With most university assessments there is no need for word art or titles with oversized text. A bold title aligned to the left is usually more than enough.

The assessment instructions usually stipulate the program you should use for the task. This can be difficult for Mac users as most assessments are expected to be handed in as Word documents. If you are going to convert your files (perhaps from Pages to Word), make sure they will open. It is your responsibility to retain copies of your work if the lecturer cannot mark it due to it being in the incorrect format.

5.4 Academic writing is messy

Academic writing is a messy process; a piece that you thought was clear one day can seem convoluted the next. Remember that writing is a craft and strong writers write often. Here are a few ways that you can hone your writing skills.

Dealing with writer’s block

It is common to feel writer’s block when you are starting an assessment, but there are a few ways to get past it. Set a timer for 5 minutes and write down everything you know about the assessment topic without regard for grammar or spelling. This is called a ‘stream of consciousness’ and, while you will not keep most of what is written, you will find a few sentences to help you start your assessment. Another way to address writer’s block is to talk about your thinking with someone to help you organise your ideas. It is sometimes helpful to talk to someone who is not completing the course or unit you are, as it forces you to focus on clarity. Drawing diagrams or mind maps using the notes or course/unit materials concerning the assessment topic, or developing a question bank, are also useful tools when you are stuck. Experimenting with different ways to get yourself started on the task will make it easier for you to focus in the long run.

Analysing the question

When you receive a question to respond to in essay or report format, ask the following questions to help you focus your assessment response:

- What is the main topic or theme of the question?

- What do the words in this question mean?

- How many sections will be needed to respond to this appropriately?

- What will these sections look like? What will they include?

- Is the question open-ended or specific and how will this impact your assessment response?

- What gaps do you have in your knowledge when answering this question and how can you address them?

- What evidence will you need to support your assessment?

- What position (for, against, or neutral) will you take on this assessment and why?

- What structure would be best used to respond to this question?

These questions are designed to help you organise how you are going to respond to the essay assessment question. You may wish to add to this list based on the feedback you receive on your assessments.

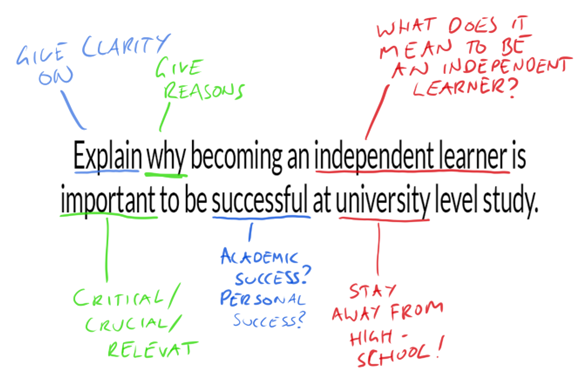

Finding the keywords

When analysing your task, highlight the keywords of the question. An assessment that asks you to ‘explain’ is different to a question that asks you to ‘consider’ for instance. Key terms also align closely with the content of the course or unit. Make notes on the keywords, highlighting your knowledge and understanding. It would be useful to divide your keywords into: Instruction words (words that tell you what to do), Content words (words that tell you what the topic is), and Limiting words (words that define the scope of the question – the where, when, and how).

Organise your materials

When researching for your assessment task, make sure you take accurate notes, including where you sourced your ideas from. Take care in making notes that are easily followed and understood. You do not want to be searching through a mass of papers when it comes time to apply the finishing touches to your assessment.

Structure

University assessments, such as essays, typically follow a standardised structure: introduction, body paragraphs, conclusion, and list of references. The purpose of the introduction is to provide background information on the topic and outline the overall thesis statement. The introduction should be brief but not lacking in detail. The body paragraphs are written to support the overall thesis statement or argument(s) of the essay. Body paragraphs offer evidence or examples, an analysis of each argument, and contain transitions between and within paragraphs to help with writing flow. How many body paragraphs you include can be dependent on the type of task you are completing, but do not be afraid of including several to help you analyse the intricate details of each argument. The conclusive paragraph, or conclusion, similar to the introduction, should be to the point but not lacking in detail. Conclusive paragraphs summarise the main arguments in the context of the body paragraphs. A list of references is always included at the end of the assessment. This reference list includes everything that you referenced in your assessment. If you are asked to include a bibliography, then you are to include all sources that you read, but did not necessarily cite directly.

Being open to redrafting

Redrafting your assessments is an important part of increasing your clarity. Being open to revising your work becomes more essential as you progress in your courses or units and the expectations are higher. There is no need to completely rewrite an assessment if it is effective, but looking for common mistakes in your clarity and expression and listening to the feedback you have received will help you to develop your writing skills.

Walking away and giving it time

If it is possible, try to factor in time away from the task as this will help you to gain perspective on your writing as well as your understanding. Many academics call this being ‘too close to the task’, making it easy to gloss over potential issues in your work. Being your own editor means that you will become familiar with the mistakes you commonly make. Getting some distance from the task can help you to see these mistakes with clarity.

Reading aloud

Reading your assessment out aloud can help you better ‘listen’ to how your writing sounds. If you feel awkward reading out loud, you can use the ‘read aloud’ function of your program to listen to your writing and see how it can be improved. You can also read your assessment to a spouse, peer, friend, sibling, or other family members as they can provide you feedback on sections that did not make sense or need further editing.

While writing is a messy process, there are several practical tools to help refine your assessments. As you progress on your learning journey you will find that gathering everything you need to analyse the assessment question or topic will become easier and mostly second nature with practise. Once this happens, you can focus on developing your writing clarity even further.

5.5 Features of academic writing

There are a few important features of academic writing that are worth considering. It can be useful to remember that the purpose of academic writing is to clearly communicate complex ideas. It is therefore necessary to use formal language. Formal language does not use clichés or slang terms to communicate because they can be ambiguous and difficult to decipher. It is also important not to confuse formal writing with overly wordy and flowery writing. When it comes to academic writing, simplicity is key. Additionally, formal language is never emotional, unless it is asked of you in a reflective piece of writing. Emotional appeals are not needed in academic writing because the findings are based on researched evidence, not emotional reactions.[1]

Academic writing draws on well-researched source material to support the overall argument while remaining closely aligned with the assessment criteria. Strong assessments critically analyse the assessment question or topic and offer specific insights into the course or unit. Understanding the course/unit content well helps. Additionally, strong academic writing shows attention to detail: grammar and syntax use are correct and the assessment is cohesive and easily followed.

Reading academic assessments can help you develop a sense of what academic writing should look like in your chosen field of study. Spend some time reading previous responses to assessment tasks and see how you might be able to refine your approach.

Below is a poorly written paragraph that is missing formal language. Try to edit the piece for additional clarity and analysis. When you are done, compare it to the rewritten paragraph below and reflect on the different language used.

Poorly written paragraph:

Independent learning is really important when you start studying at university. It’s a time when you need to figure out how to study by yourself without relying too much on your teachers. Self-efficacy is something you should develop because it makes you confident that you can handle your studies. Also, you should understand who you are as a learner because it will help you know what works best for you when studying. If you know how you learn, it will make things easier and help you do better in your courses.

Revised paragraph:

Striving to develop independent learning skills is essential when beginning university study. Transitioning to higher education requires autonomous study, with less reliance on your lecturers. It is important for students to cultivate their self-efficacy, as it fosters the confidence necessary to manage academic responsibilities. Additionally, reflecting and gaining a deep understanding of learner identity is vital for student growth, as it can help identify and apply effective and bespoke study strategies. A comprehensive understanding of a learner identity can lead to improved academic performance and growth.

5.6 Common mistakes in academic writing

Researchers have known how complex academic writing is for a very long time. Good writing is more than just learning rules, it requires the integration of evidence within the topic through explanations, modelling, and addressing feedback (Wingate, 2006). To that end, it is important that this section is considered holistically, and should not be treated as a definitive list. Strong writing involves a knowledge of what to include as well as what to avoid. These are some common minor mistakes students make when they write assessments for the first time.

Discussing an article

You need only include relevant information of the articles you have read. Articles are used to simply attribute ideas to the author. You can see Chapter 7 for more advice on citations, but including elements like the article title, or where the article was published, is not normally needed in the body of the assessment.

Failing to support ideas/arguments

Unless you have attributed an idea or argument to an article, textbook, or thinker of your chosen discipline, it will be seen as unsupported and somewhat irrelevant. Evidence should be gathered first and then used to create the arguments in your assessment, not the other way around. Let the evidence tell you how you should argue your points. This is where your note-taking is especially important as you will be able to support your arguments well if your notes are organised.

Missing the question or topic

Make sure your assessment answers the entire question or addresses the topic. For a question like “Explain why becoming an independent learner is important to be successful at university level study”, forgetting to discuss ‘success’ would lead to an unfinished assessment that fails to respond to the question. Similarly, writing about high school experiences when responding to this question misses the point of what the question is asking.

Incorrect citations

Citations are covered in Chapter 7, but incorrectly attributing ideas or failing to attribute them at all are common mistakes in academic assessments that can impact your performance.

Problems with ‘I’

‘I’ should only be used for particular assessments such as reflections. At no time should a regular essay assessment contain ‘I’, as your opinion is not what is asked for; your understanding is. This point also applies to other personal pronouns, such as ‘you’, ‘we’, and ‘us’, which are also best not used in these assessments.

Incorrect language

Formal language is discussed above, but this is a common issue in first year writers. Practice your formal language often to increase your skill.

Leaving points as self-explanatory

Try not to assume that the points you make are self-explanatory. While over-explaining might make your assessment difficult to follow, it is important that you explain your points fully so your assessor can see your understanding. Striking a balance between explaining your point and not waffling on is the key here.

Introduction issues

Some students write introductions that are too long or do not include all arguments that will be presented in body paragraphs. Make sure your introductions clearly state all arguments and are as concise as possible.

Not quoting the readings from the course or unit

As your lecturers are generally experts in the discipline, they include readings that are vitally important to understanding the concepts of the course or unit. Not including references to these readings makes it very difficult to show a deep understanding of the courses or units’ key points.

Using obscure or out of date references

Part of researching means finding sources that are strong, relevant, and current. If you find a source that discusses your idea but is set in another country, it might not speak to the experiences you are analysing and is therefore not worth using. Similarly, most academics only accept references published within the last 5 or 10 years. Unless what you are referencing is the original text of a great thinker in your discipline area, focus on finding current articles that are relevant to your assessment topic.

Again, this is not an exhaustive list when responding to university assessments, and it is best not to consider these points in isolation. Practice your writing and listen to any and all feedback you receive. Learning to write well is a continuous skill that takes time to refine.

5.7 Key strategies from this chapter

- Start assessments early: Begin thinking about the task before you start writing. Discuss the task with peers, lecturers, and support networks to clarify your understanding.

- Gather resources: Ensure you have all necessary materials like readings, notes, and access to databases before beginning. Request past student work for guidance.

- Use visual tools: The Generate-Sort-Connect-Elaborate routine, or a simple mind-map tool, can help you to structure your thoughts and identify gaps in your understanding.

- Read assessment instructions carefully: Pay attention to all requirements (spacing, font, formatting, word count etc.) and be concise in your response.

- Overcome writer’s block: Streams-of-consciousness, talking through your ideas, or using diagrams and mind maps are all effective ways to address writer’s block.

- Analyse the question: Identify keywords and break down the question to gain clarity on assessment expectations.

- Support all arguments: Make sure all your arguments are supported with credible sources.

- Realise that writing is messy: Be prepared to redraft and revise your work. Strong academic writing requires reflection, practice, and willingness to improve.

- Understand academic writing: Use formal language and focus on clarity of writing in your assessments.

5.8 Chapter summary

In this chapter we have:

- recognised the elements needed for writing success.

- examined how planning and preparation can positively impact your academic assessments.

- examined how tools such as mind maps can be used to explore thinking and clarify meaning.

- highlighted the importance of following instructions meticulously, including formatting, and submission guidelines.

- explored the skill of writing including using evidence to support an academic argument or points.

- considered common mistakes made by first-year students.

5.9 Reflection questions

- What personal challenges have you faced when starting university tasks, and how can you better understand these challenges to improve your approach?

- How can starting your assessment early impact your overall performance? What strategies might you use to ensure you begin your tasks promptly?

- How can visual planning tools like mind maps and the Generate-Sort-Connect-Elaborate Thinking Routine assist in organising your thoughts and planning your assessments?

- Reflect on a time when you missed an important instruction in an assessment. How did it affect your work, and what will you do differently in the future?

- Share a technique you have used or could use to overcome writer’s block. How does this technique help you in the writing process?

- How do the features of formal academic writing differ from informal writing? How can you ensure your writing adheres to academic conventions?

- What common mistakes do you often encounter in your writing? How can recognising and addressing these mistakes improve your writing quality?

References

Christie, H., Tett, L., Cree, V. E., & McCune, V. (2016). ‘It all just clicked’: A longitudinal perspective on transitions within university. Studies in Higher Education, 41(3), 478-490. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2014.942271

Hassel, S., & Ridout, N. (2018). An investigation of first-year students’ and lecturers’ expectations of university education. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 2218. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.02218

Hawe, E., Lightfoot, U., & Dixon, H. (2019). First-year students working with exemplars: Promoting self-efficacy, self-monitoring and self-regulation. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 43(1), 30-44. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2017.1349894

Wingate, U. (2006). Doing away with ‘study skills’. Teaching in Higher Education, 11(4), 457-469. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562510600874268

I would love to hear your thoughts on this chapter, share your feedback.

- Even if the study is on emotional reactions, the writing itself will not be emotional. ↵