Chapter 9: Dealing with anxiety and developing emotional intelligence

Liam Frost-Camilleri

Learning Objectives

- Recognise the importance of emotional intelligence and how it relates to emotional regulation, resilience, and well-being.

- Identify the key components of emotional intelligence using models such as Goleman’s clusters and Cooper & Petrides’ dimensions.

- Understand the role of emotional vocabulary and its significance in identifying and processing emotions.

- Develop strategies for building emotional intelligence and resilience to manage anxiety.

You may have noticed that much of this textbook is concerned with navigating emotions. Arguably, frustration with the lack of resources of this nature was the primary reason for writing this textbook. This is because emotional regulation always precedes academic expectation. Being emotionally regulated ensures that you have the capacity to deal with any issues that may arise, and to recognise, identify, and work through your emotions, you need to be emotionally intelligent.

This section explores the recognition and development of emotional intelligence and resilience, however, it is important to note that not scoring highly on an emotional intelligence test, or reading ideas in this chapter that are new and challenging, does not mean you are ‘unintelligent’. ‘Intelligence’ is simply the term that we use to discuss this idea.

9.1 Emotional intelligence

Emotional intelligence tends to reside in three overlapping areas: being aware of your emotions, being able to manage your emotions, and having positive relationships with others. Being aware of your emotions requires you to be in tune with your body, paying attention to how it reacts to different situations while understanding how your past experiences may inform these reactions. Being able to manage your emotions does not mean ignoring or removing them; it means being able to ‘ride the wave’ of emotion without it causing distress or dysregulation. Having positive relationships with others refers to expressing empathy and maintaining satisfying and comfortable connections. Reflect on how aware you are of your emotions, if you successfully regulate yourself, and if your emotions impact your relationships.

Research has found many benefits to being emotionally intelligent, including higher levels of contentment and better navigation of the workplace. This chapter introduces two main models that explain emotional intelligence well.

Goleman et al. (2002) developed a model that discusses four clusters that encapsulate emotional intelligence. These clusters are:

Self-awareness. Having an awareness of your own emotional state, which includes accurate self-assessment and self-confidence.

Self-management. Exercising self-control, maintaining honesty and integrity, and being flexible and adaptive to the emotions you are feeling.

Social awareness. Empathising with others, being aware of emotional currents in everyday life, and recognising the emotional needs of others.

Relationship management. Leading and developing other students, persuading with integrity, resolving conflict, and building connections with others.

Each of these clusters is quite complex, but this snapshot gives you an idea of what Goleman et al. (2002) aimed for when they described the various facets of emotional intelligence. Goldman’s research highlights that people with high emotional intelligence enjoy more financial stability, are more productive, and tend to build more supportive work environments (Goleman et al., 2022).

Another framework worth considering was created by Copper and Petrides (2010), who also incorporates four dimensions:

Well-being. A sense of well-being about the past, present, and future, leading to happiness and fulfilment.

Self-control. The ability to control urges and desires.[1]

Emotionality. The ability to perceive and express your emotions while using them to aid your relationships.

Sociability. The development and maintenance of relationships, with a focus on social rather than romantic ones.

There are also emotional intelligence tests that can be taken to give you an idea of areas you could develop. This test uses Goleman’s clusters model discussed above: https://globalleadershipfoundation.com/geit/eitest.html. This survey might not be the most accurate, but the results may give you an indication of what you would like to focus on.

From these models we can start to understand how to grow our emotional intelligence. There is more on this idea below, but in the meantime, we need to acknowledge that developing emotional intelligence is challenging and takes time. A strong first step is learning emotional-specific vocabulary to help you accurately discuss your emotions.

9.2 Emotional vocabulary and literacy

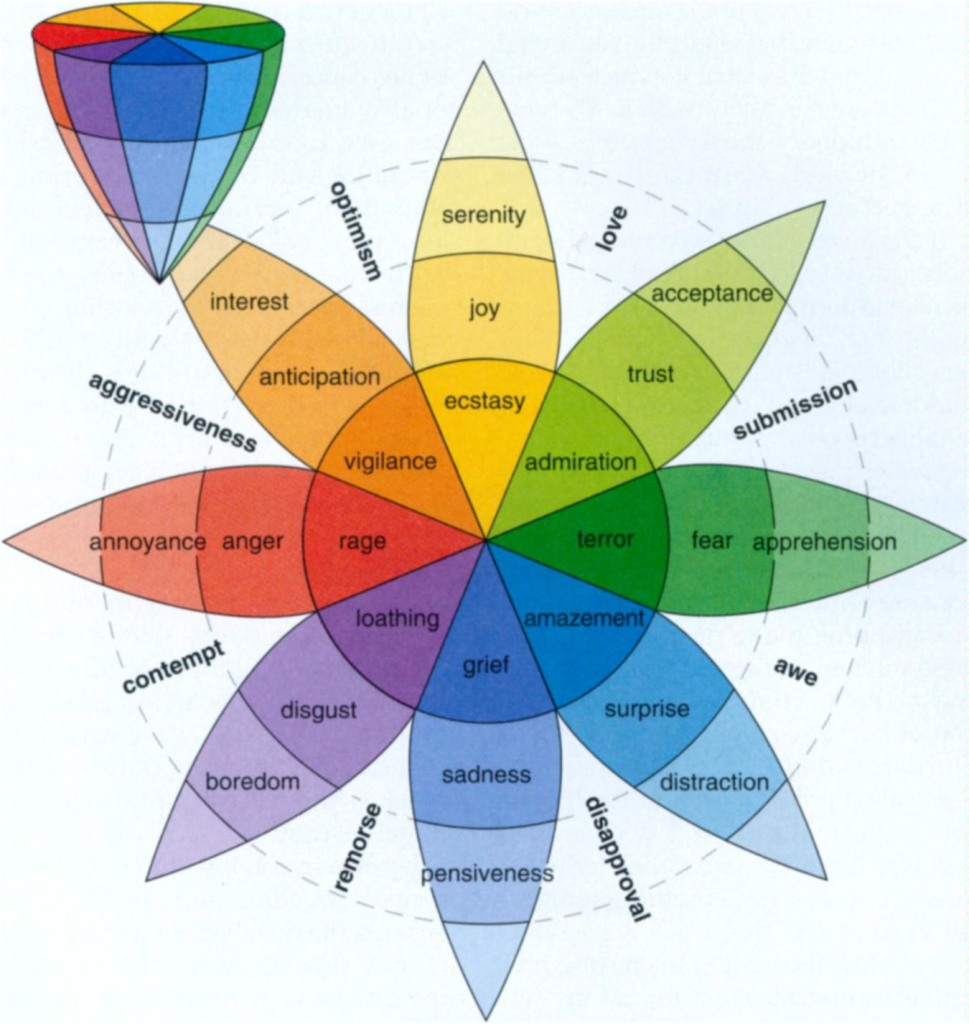

An emotions wheel organises a spectrum of human emotions into a ‘wheel’ configuration, making it easier to connect the labels of related emotions. The first emotions wheel was created by psychologist Richard Plutchik who placed eight overarching emotions in the centre, and linked them to other more complex emotions, as can be seen in this figure below (Plutchik, 1980).

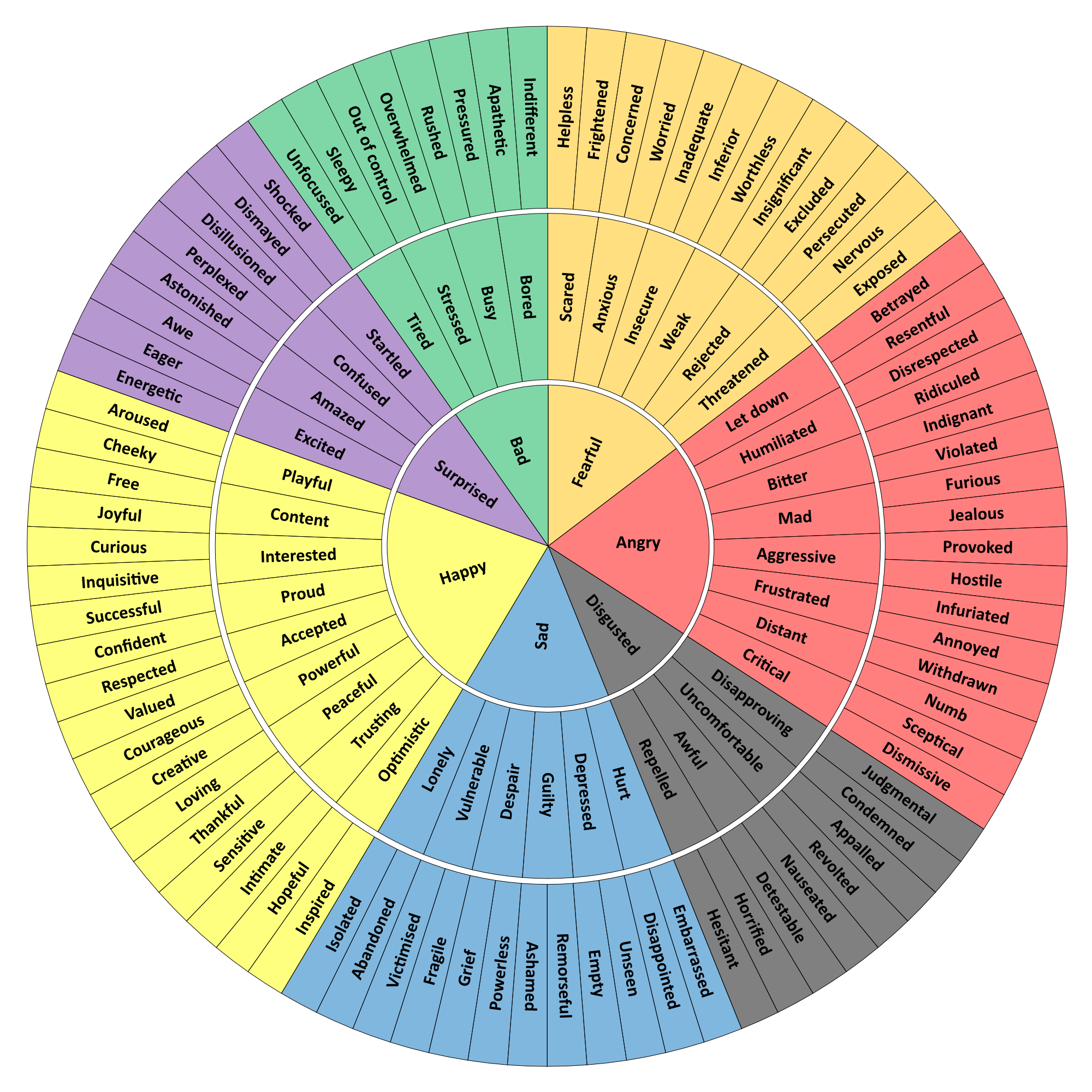

Plutchik’s concept inspired a variety of different emotional wheels that can help develop your vocabulary. Some are divided into comfortable and uncomfortable emotions, while others simply discuss feelings in general. There are many emotion wheels available, and they all have merit. Here is another example to help you learn the vocabulary needed to discuss emotions effectively.

This emotional word wheel is an example of how many people and organisations have extended on Plutchik’s original work. The centre emotions are simplified, allowing more room for the variety of feelings we experience in the outer circles of the wheel. One thing that all emotion wheels have in common is that they break down ‘primary’ emotions into their many facets. For instance, ‘sad’ is broken into ‘hurt’ ‘depressed’ ‘guilty’, ‘despair’ ‘vulnerable’ and ‘lonely’. Therefore, following the line of ‘sad’ may lead you to discuss feeling ‘lonely’ or ‘isolated’. The more terms you can use to pinpoint what you are feeling, the better you can understand and address your emotions.

You may also disagree with certain facets of this wheel, and many wheels categorise feelings differently. For instance, you might not equate feeling ‘sensitive’ with feeling ‘happy’, or feeling ‘fragile’ with feeling ‘sad’. Discussing where these emotions fit in with your individual experience is an important part of developing a meaningful emotional vocabulary. Now that you have a better understanding of emotional vocabulary, it is time to discuss how to develop emotional intelligence and resilience.

Using the template in the downloadable pdf, create your own emotions wheel. Try to identify a series of primary emotions that you can break down into more specific ones. Reflect on your choices and which emotions were harder for you to break down than others. What might this tell you about your ability to identify and work with emotions?

9.3 Resilience and developing emotional intelligence

Resilience and emotional intelligence are related terms. While emotional intelligence refers to understanding and regulating your emotions and connections, resilience involves having the tenacity to continue trying despite challenges (Chung et al., 2017). Many of the tools that you have encountered so far connect strongly with building resilience and emotional intelligence, such as developing a growth mindset, or curating self-efficacy (Margo et al., 2019). But there are other ways you can develop important skills as follows:

Self-care. Caring for yourself requires responding to your needs, ensuring you have the capacity to handle your responsibilities and tasks. Self-care looks different for each person, so it is important to remain curious in this area.[2]

Help seeking behaviours. Understanding that you are not alone in your journey is an important aspect of emotional intelligence and resilience. People who are emotionally intelligent and resilient do not try to ‘go at it alone’ and actively seek help when they need it.

Exposure to challenges. Successfully navigating challenges builds your confidence and resilience. These challenges should be approached with appropriate supports, but success in one area can help you apply similar strategies to other situations.

Seeing others navigate challenges. Having others model how they navigate challenges provides strategies and knowledge that you can use. It is important not to focus on the differences between yourself and the other person in this process, as this can prevent you from internalising the successful strategies they used.

Reflection diaries. Keeping a diary about your emotions and challenges has been known to develop both emotional intelligence and resilience. This diary does not have to be formal and can be a video diary if you feel more comfortable.

Sleep hygiene. Sleep hygiene is crucial for building your capacity for resilience. Consider your sleep schedule, and try to go to bed and wake up at the same time each day. Develop a routine before bedtime to help you wind down. Limit screen exposure before bed to help reset your melatonin, the sleep hormone. Create a comfortable sleep environment, and limit naps taken during the day. Sleep hygiene may take time to develop, but it is essential in your journey toward resilience and emotional intelligence.

There is a clear connection in the research literature between resilience, student academic success and general well-being (Chung et al., 2017). The challenges you face are complex, requiring a complex response to navigate them successfully. For this reason, sharing what we know with others and paying attention to how resilience is modelled are especially helpful strategies (Margo et al., 2019). Another important way you can develop your resilience effectively is by addressing anxiety.

Spend a week keeping a diary of your emotions. This diary can be created online or handwritten. Try to write in your diary at key points throughout your day, such as in the morning, at midday, and at night. When the week is over, complete a reflection that considers the emotions you felt throughout the week. Did you find any patterns? Which emotions where the most troubling for you and what might you do to address them in the future?

9.4 Addressing anxiety

As we are discussing the importance of recognising and regulating emotions, it is imperative to consider one of the most commonly uncomfortable emotions that many students experience: anxiety. This section is not referring to clinical or diagnosed anxiety disorders, and the following is not medical advice. This section is only written in the context of feeling anxious when beginning a university course.

As established earlier in this textbook, experiencing anxiety can provide valuable information about what is happening for you emotionally. Before we discuss how to manage your anxiety, it is important to understand that we do not get rid of anxiety, we merely manage it, and managing anxiety can be different for each of us. The following strategies were developed by academic Olivia Remes, who has spent much of her research looking into ways that anxiety can be regulated scientifically.

Recognise it. The first step in addressing your anxiety is what is sometimes called ‘name it to tame it’, or simply recognising the anxiety you are feeling. Remes (2021) explains that anxiety is both a feeling of fear and restlessness. Think about how these two feelings appear in your body so when you feel anxious, you can recognise it early.

Self-control. Remes (2021) endorses the idea of developing good habits and suggests that self-control is like any other muscle, the more you use it, the stronger it will become. Interestingly, the research demonstrates that exercising self-control in one aspect of your life can make other areas easier to control.

Set boundaries. The setting of boundaries can be as small as removing the news from your phone or politely declining a social invitation when you need to spend time looking after yourself. Setting boundaries is something you need to consider for yourself, and lowering access to, or time spent in, anxious situations helps to lower your anxiety (Remes, 2021).

Embrace the environment. There is a lot of research on the healing effects of going outside and into nature. Some research even indicates that looking at pictures of nature can reduce anxiety. Remes (2021) takes this one step further to focus on the senses while in nature. Crumbling leaves in your hand, and feeling rocks or bark can all help you feel more connected to nature and less anxious.

Mindfulness and meditation. There is such an abundance of information about meditation and mindfulness that this textbook only focuses on the basics as a starting point. The research tells us that meditation and mindfulness not only alleviate stress, but can lower blood pressure, strengthen your brain, and increase your capacity for compassion. But mindfulness and meditation does not have to be done in the corner of a room with incense, low light, and calming music. You can be mindful in many situations, like while washing the dishes, or while you stare outside finishing your cup of coffee. The important point is to take opportunities to be mindful when you can. If you want to move into mindfulness more, but are unsure where to start, joining a local meditation group could be a good first step.

Do it badly. The idea of ‘doing it badly’ refers to removing expectations of doing something perfectly the first time. Being self-compassionate in this way gives you freedom from procrastination and indecision, allowing you to develop your skills slowly (Remes, 2021).

Self-compassion and forgiveness. As Remes (2021) argues, we often find it easier to be compassionate towards others than to ourselves. Reflecting on the critique you are giving yourself and asking whether you would give that critique to someone else could help you muster self-compassion. Learning how to forgive yourself can break your cycle of self-criticism.

Exercise. There is a lot of research that supports the benefits of exercising for lifting mood. Remes (2021) offers the advice of combining ‘do it badly’ with exercise, making you feel less self-conscious and more able to overcome potential barriers to physical activity.

Creating positive activities. Remes (2021) emphasises the importance of planning activities that bring positivity to your life. Given how stressful our lives can be, planning for positive situations can have a remarkable effect on our ability to regulate anxiety.

Other research discusses the importance of diet, challenging negative self-talk, and advocating for yourself when trying to regulate anxious emotions. You will notice that many of these practices are exercises to do before you feel anxious. Meditating while you are in a heightened state is only effective if you are well-practised at meditation. Practising something when you are emotionally neutral makes it easier to do when you are feeling anxious. In the meantime, think of ways that help you calm down and feel positive, whether that is dinner with friends, gaming, or going for a run. Pay attention to how these strategies help you regulate and build resilience, and use them often.

Developing your emotional intelligence, vocabulary, resilience, and capacity to regulate anxiety are all rather large tasks that take time and patience. Be compassionate with yourself in this space and try developing these skills through journaling, reflecting, and discussing with others.

9.5 Key strategies from this chapter

- Understand emotional intelligence: Becoming aware of your emotions, managing them, and developing relationships are all effective ways of improving your emotional intelligence.

- Build emotional vocabulary: Acknowledge and work through your emotions using tools like an emotions wheel to expand your vocabulary and increase your emotional intelligence.

- Build resilience: Build your skills in resilience by prioritising self-care, help seeking behaviours, exposing yourself to challenge, reflective journaling, and sleep hygiene.

- Manage your anxiety: By recognising and acknowledging your anxieties, exercising self-control, setting boundaries, embracing nature, practicing mindfulness and self-compassion, and exercising regularly, you can work to manage your anxieties.

9.6 Chapter summary

In this chapter, we have:

- explored how emotional intelligence encompasses three key areas: being aware of emotions, managing them, and maintaining positive relationships.

- examined the role emotional vocabulary plays in understanding and processing emotions.

- discussed how the concepts of resilience and emotional intelligence are related.

- examined how managing anxiety is a key aspect of emotional regulation, particularly in stressful situations like starting university.

- explored strategies for managing anxiety including recognising anxiety early, setting boundaries, engaging with nature, practising mindfulness, and embracing self-compassion and exercise.

- understood how developing emotional intelligence, resilience, and anxiety management takes time, patience, and self-compassion.

9.7 Reflection questions

- How aware are you of your emotions in different situations, and how do they impact your behaviour and decision-making?

- When faced with emotional challenges, what strategies do you currently use to manage your them? Are they effective?

- How would you describe your emotional vocabulary? Do you feel you have the language to accurately express your feelings?

- In what ways have you demonstrated resilience in your academic or personal life? How can you strengthen this skill?

- What methods have you found most effective in managing anxiety? How might you improve your anxiety regulation in the future?

- How can you incorporate self-compassion into your daily life, especially when dealing with emotional challenges or failures?

- How can you become more mindful in everyday situations?

References

Brewer, M. L., van Kessel, G., Sanderson, B., Naumann, F., Lane, M., Reubenson, A., & Carter, A. (2019). Resilience in higher education students: A scoping review. Higher Education Research & Development, 38(6), 1105-1120. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2019.1626810

Chung, E., Turnbull, D., & Chur-Hansen, A. (2017). Differences in resilience between ‘traditional’ and ‘non-traditional’ university students. Active Learning in Higher Education, 18(1), 77-87. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469787417693493

Cooper, A., & Petrides, K. V. (2010). A psychometric analysis of the trait emotional intelligence questionnaire-short form (TEIQue-SF) using item response theory. Journal of Personality Assessment, 92(5), 449-457. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2010.497426

Edwards, M. S., & Ashkanasy, N. M. (2018). Emotions and failure in academic life: Normalising the experience and building resilience. Journal of Management & Organization, 24(2), 167-188. https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2018.20

Goh, E., & Kim, H. J. (2021). Emotional intelligence as a predictor of academic performance in hospitality higher education. Journal of Hospitality & Tourism Education, 33(2), 140-146. https://doi.org/10.1080/10963758.2020.1791140

Goleman, D., Boyatzis, R., & McKee, A. (2002). The emotional reality of teams. Journal of Organizational Excellence, 21(2), 55-65. https://doi.org/10.1002/npr.10020

Goodchild, T., Heath, G., & Richardson, A. (2023). Delivering resilience: Embedding a resilience building module into first-year curriculum. Student Success, 14(2), 30-40. https://doi.org/10.5204/ssj.2883

Karimova, H. (2017). The emotion wheel: What it is and how to use it. PositivePsychology.com. Retrieved from https://positivepsychology.com/emotion-wheel/

Plutchik, R. (1980). A general psychoevolutionary theory of emotion. In R. Plutchik & H. Kellerman (Eds.), Emotion: Theory, research, and experience (1), 3-33). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-558701-3.50007-7

Remes, O. (2021). The instant mood fix: Emergency remedies to beat anxiety, panic or stress. Random House.

Willcox, G. (1982). The feeling wheel. Transactional Analysis Journal, 12(4), 274-276. https://doi.org/10.1177/036215378201200411

I would love to hear your thoughts on this chapter, share your feedback.

- It is worth noting here that anybody reading this with ADHD that a lack of ability to control urges is more due to lower dopamine levels than emotional intelligence. Many of these theories are based in psychology and tends to use a neurotypical understanding of concepts. ↵

- A note for any parents who struggle in this area. It can be very difficult to find time when you are responsible for a little one, so it would be worth mustering any supports you can and maybe finding smaller ways to care for yourself. ↵