Chapter 2: Independent learning and self-efficacy

Liam Frost-Camilleri

Learning Objectives

- Define independent learning and discuss its importance in a university setting.

- Understand and develop strategies to foster self-efficacy and a growth mindset in a university context.

- Identify and evaluate different support systems available at universities.

- Discuss the role of lecturers, tutors, and external support networks in student success.

2.1 Independent learning

Independent learning is an all-encompassing term that contains a wide variety of skills when it comes to learning at university. Most definitions point to autonomy, or a self-led approach to learning that prioritises the student ‘taking control’. For example, Holec (1991) states that independent learning is “the ability to take charge of one’s learning” (p. 3), whereas Levy and Treacey (2019) claim that “a successful independent learner is one who has adjusted to the culture of the university” (p. 34). This taking control involves deciding what, when, and how to learn. It involves being able to evaluate yourself and reflect on what you have learnt, and it also requires you to create your own objectives. That is why there are so many definitions of ‘independent learning’ and why they are all correct in different ways. The term highlights how different learning at university is compared to secondary school or other forms of education.

To be a student who is independent, or who ‘takes control’ of their learning, it is important to consider the expectations of the tasks that require completion. If a course has an essay as an assessment task (which is very common at university), then a variety of different independent skills need to be drawn upon to complete it effectively. Research will be required to find suitable material for the essay. Reading and analytical skills will be used to decide what is and is not relevant to the assessment. Understanding the conventions of academic writing, such as how to use citations and the expected language of an essay, is also important. Consideration needs to be made to the planning, structure and the main purpose of the assessment to ensure it responds appropriately to the question or topic well. A student would even have to consider how to manage the task of writing the assessment by predicting how long it would take to produce.

All of these tasks (and more) are involved in becoming an independent learner, but these aspects can change based on what is expected of each university assessment. For example, group work or presentations require a whole different set of skills, including communication, people and conflict resolution skills. It could also be argued that class activities or the type of class (lecture, tutorial, workshop etc.) require independent skills in listening, effective note-taking, asking insightful questions and self-reflection, all at different levels depending on the expectations of the class.

When analysed closely, it seems that being an independent learner requires many new skills that most novice students might not yet possess. While being an independent learner is a university expectation, there is also an understanding that these skills are still in development and will take time before they become effective. This is where reflecting on your skills and identifying the areas you would like to develop or improve upon can be especially helpful. Using a blanket term such as ‘help’ when asking for support fails to pinpoint the actual problem you might be having. However, if you have reflected on your abilities and determined that you need to work on your note-taking skills for example, then you can be more specific about the support you need. Thus, it is very important to ask yourself the following question often: “What could make me a better independent learner?” Remember that while becoming or being an independent learner requires you to be autonomous, you do have a great deal of support behind you. Being an independent learner is not the same as being on your own and not seeking support.

2.2 Support

Most universities have different levels of support available. The most obvious support comes from the lecturers and tutors that you encounter, but they are primarily employed to work through the content of the course or unit with you. They can clarify something that does not make sense to you or help you refine your analysis, questions, and response to assessments. It is important to note that in most universities, lecturers do not accept drafts of assessments but can talk more generally about your approach. Once the student’s needs move away from content and towards elements like study skills, lecturers and tutors might not be the best people to engage with.

Generally, universities have a support network for the ‘soft skills’[1] required, usually run by a student body, library, or student support space. Many of these networks are comprised of former students or people who specialise in student support. If you have or suspect you have a learning disability, there is also a disability support service to engage with. It is important to consider the many supports Universities offer students, as they may be of benefit to you. A general inquiry will usually point you in the right direction.

It is also worth mentioning other supports you might be able to engage with outside of the university. Local librarians, anybody you know who has attended university, teachers, nurses, or anybody who has studied before may offer valuable insights into how they navigated becoming an independent learner.

2.3 The ‘perfect’ student

The topic of ‘independent learner’ is often referred to as ‘becoming’ or ‘being’ an independent learner. However, given the complexity of the term and the fact that some days we can be our best selves and other days we can struggle to analyse, read, listen, or comprehend what is going on, it is better to think of independent learning as something we pursue or strive for rather than something that we are. The concept that there is a perfect student who always understands everything happening in class or in their assessment pieces is, to put it plainly, a myth. Every student has had to work on their skills in different ways, and some students might have to work on developing certain skills a little more than others. You may have a vision of the student you wish to be, but be kind to this version of yourself. Misunderstanding a reading or not participating in one of your classes is not a cause for concern. Many students who are starting university feel that they need to change much of themselves before starting and become highly disciplined and exceptional students. Being this studious can be quite unrealistic once you become aware of the new set of skills required to navigate university. Try to meet yourself somewhere in the middle: Strive to be the best student that you can be, but forgive yourself if you fail to reach the ‘perfect’ student ideal that you have in your mind.

Learning Activity 2.1 Self-Reflection and Planning Exercise [PDF]

One of the important parts of self-reflection is being able to take stock of what you do well and what you can develop further. In the interest of developing your abilities, use the following list of skills to reflect on your current ability and how you might develop it further:

- Written and other communication skills

- Research skills

- People skills

- Thinking skills

- Task management skills

- Time management skills

- Confidence

- Resilience

- Organisational skills

2.4 The importance of questions in learning

In most courses at university, beginning the class with one question and ending it with another 20 is usually a sign that the class is working well. Most lecturers want you to think deeply about what you are learning, and discussing potential solutions to questions can help you to explore the content effectively. At university, statements are often turned into questions to help reframe and analyse course or unit content.

For instance, if we take the concept of independent learning and frame it as a question: “What is an independent learner?” We might try to answer the question by highlighting autonomy. The question could then be asked, “What does it mean to be autonomous?” After creating a list of what it is to be autonomous: you could ask the question, “What do I need to develop to be autonomous?” You might settle on asking more questions in class, which could lead to the question, “What type of questions should I ask?” and so on. The point is, questions lead to more questions, which might be uncomfortable when you are a student, but asking questions at university is seen as part of the learning journey. Consider what your courses or units are about and what questions you can keep alive in your mind to help you maintain interest and refine your understanding.

2.5 What university classes look like

Traditionally, most university classes consisted of lectures and tutorials. Lectures are classes with many students where the lecturer quickly covers the content and the students are expected to listen and take notes. There are usually few opportunities to ask questions in a lecture. Tutorials, on the other hand, are smaller groups of students and typically involve asking questions and discussing the lecture content with a tutor. The main advantage of a lecture is the ability to cover content quickly, while the main advantage of a tutorial is being able to discuss the content and ask questions. However, with more people now attending university, many institutions have begun to change their format. Most classes are now workshop or seminar-based, which involve small group work, elements of a lecture, and some interactive activities. Other types of classes include labs, where you conduct experiments or do hands-on work, and placements, where you connect with a workplace that grades you on your performance. Some universities offer purely online or blended (that is, blended between face-to-face and online) models of instruction, better catering for students with family and/or work commitments. Understanding the format of your classes will help you successfully navigate them, so try to have a conversation with your lecturer about what is expected of you in class.

Universities offer choices of study modes for students. Generally, these are divided into on-campus and online models, with a blended or hybrid model where you can attend classes purely online or attend only a few sessions throughout the semester. Each mode offers unique challenges and advantages. On-campus study gives you personal interaction, a structured environment, and direct access to campus facilities, but can become challenging with time constraints and the cost of travel. Online study provides flexibility in your study by making it self-paced and always accessible online, but can present challenges of isolation and the increased need for self-discipline. A recent study found that attitudes towards online study had a significant impact on student engagement and participation (Ferrer et al., 2022). It is important that you are clear on which study mode would work for you and why. If your attitude toward study is positive, and you enjoy the process of learning, then you may successfully navigate online study well. If you enjoy discussing content, making connections, and want to make more use of what the university offers, then on-campus study may be a better option.

2.6 Self-efficacy

The term ‘self-efficacy’ is usually confused with ‘self-esteem’, but there is an important difference. Self-esteem is how you feel about yourself, whereas self-efficacy is the belief you have in yourself. With these definitions in mind, you could have high self-esteem (feel very good about yourself) and low self-efficacy (do not believe in your abilities) at the same time. There is an old saying that seems to have turned into a punchline rather than a meaningful phrase; the idea that ‘whether you believe you can or you believe you can’t; you’re right’, more than captures self-efficacy.

Self-efficacy has been linked to people’s ability to succeed in several research studies (Ayllón et al., 2019; Zajacova et al., 2005; Van Dinther et al., 2011). It appears that believing you can succeed is more effective than simply having high self-esteem. The good news is it has been proven that you can develop your self-efficacy. Being more engaged by preparing before class, joining in on class discussions, reflecting on your abilities and performance, managing your time well, and taking care of yourself are all strategies that you can build your self-efficacy. The important point to remember is that these skills take time to develop, understand and apply.

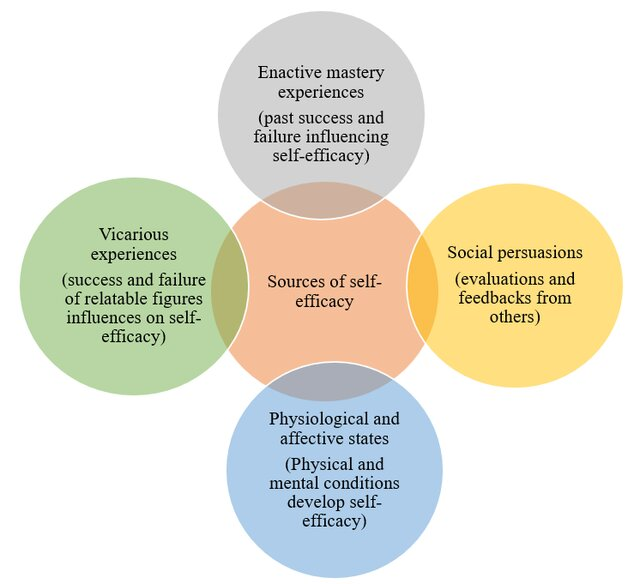

Figure 2 illustrates how Bandura (1977) believed judgements about self-efficacy are formed.

The interesting thing about these judgements of self-efficacy is how they can depend on our interpretation of them. Past experiences, like a school oral presentation that went wrong, may convince you that you are bad at oral presentations. The memory of embarrassment might create anxiety every time you are expected to present. Observing others performing poorly in a similar task can also influence your self-perception. This phenomenon is known as modelling by others. The coaching you receive may also impact your self-efficacy judgement. For instance, if your parents expressed dislike for oral presentations, you might internalise those beliefs. Lastly, because you were so anxious about the presentation, your physiological or emotional response was pushed to the limit. This self-doubt and emotional distress create a physiological feedback loop: “I do not enjoy being in front of people and having to speak”.

While these judgements might sound a little bleak, we can equally adopt positive judgements of self-efficacy in the same scenario. Drawing from past experiences may motivate you to avoid repeating the same mistakes. Thus, you practice and develop a better sense of how to present effectively. You might watch videos of great presentations and use them as models to enhance your own skills. Even if your parents expressed their dislike for presentations, you approached the situation with curiosity and resolved not to repeat their mistakes. As you gained an understanding of how to manage or even harness your anxiety, you learned to calm yourself effectively and perhaps even use your anxiety as a motivator to improve your presentation skills.

With these different perspectives on the same situation, you can see how judgements about self-efficacy can vary widely. The key takeaway is that self-efficacy can be developed, and one of the most effective methods to achieve this is by cultivating a positive mindset.

2.7 Mindsets

Carol Dweck wrote a book called Mindset: The New Psychology of Success in 2006. In it, she discussed various individuals in business, sports, and education, illustrating how they exhibited elements of either a fixed mindset or a growth mindset.

A fixed mindset is evident in people who tend to take criticism very harshly, give up easily and often exclaim ‘there’s just no point in trying’ or ‘see? I knew that I would fail.’ Individuals with a fixed mindset believe that intelligence is fixed and cannot be changed, or they attribute their failures to external factors. In other words, you are born with your abilities and they cannot be improved upon. This mindset can lead to behaviours that discourage taking on challenges, avoid responsibility, and inhibit personal growth.

People with a growth mindset, however, tend to handle criticism more positively. They understand that feedback on their work is not a reflection of their personal worth but an opportunity to improve their abilities. Those with a growth mindset might say things like ‘I can grow from my mistakes’ or ‘if I make a mistake, I can just keep trying’ or ‘I don’t know how to do it yet.’ They believe that intelligence and abilities can be developed through effort and perseverance. Embracing a growth mindset encourages individuals to welcome challenge, take ownership of their learning and strive for self-improvement.

When it comes to studying at university, it is beneficial to view mindsets as a spectrum rather than being strictly growth or fixed. Few people embody a purely fixed or growth mindset across all aspects of their lives; instead, individuals may exhibit a growth mindset in some areas and a fixed mindset in others. However, a growth mindset can be cultivated and enhanced over time, often through mindful language use. Dweck (2014) suggests that adding ‘yet’ to defeatist statements can foster a growth mindset. For instance, ‘I can’t do this yet’ instils hope and motivation to persist when contrasted with ‘I can’t do this’.

Developing a growth mindset requires conscious effort. It involves recognising and reframing negative self-talk, a process that may take time and persistence. But know that this effort will be well spent in time.

2.8 Self-talk

Self-talk refers to the internal dialogue that we have while we are learning. This internal narrative is incredibly powerful and can influence how we approach tasks and how we perceive ourselves and our abilities. Listening to our self-talk with curiosity is one way that we can start to influence it, making it more of an ally in our journey than something that can squash our motivation.

Positive self-talk can include affirmation and supportive thoughts that encourage us to persevere, build confidence, and aim for self-improvement. Consider these sentences and the impact they may have on your confidence when facing an assessment:

“I may not understand this right now, but I will figure it out with effort and time.”

“Every time I try, I get one step closer to success.”

“I trust that I will understand this in time.”

These statements can foster a growth mindset which will place you in good stead to approach the challenges presented by the university environment. Regularly using affirmations, identifying and reframing your negative self-talk, visualising your successes, and focusing on your effort rather than outcomes will help you to focus on what is most important about your learning journey.

Using a six-sided or online dice, roll and complete the corresponding mindset activity.

1 = Write down a time that you made a mistake and what you learned from it.

2 = Explain why making mistakes is a good thing for your learning.

3 = Write down a challenge you had today and how you overcame it.

4 = Explain some ways you can motivate yourself when things get difficult.

5 = Write down four mantras you can say to yourself when you are feeling discouraged.

6 = Write down strategies that you see/hear other people using and think about how you might be able to adapt their methods to suit you.

2.8 Key strategies from this chapter

- Clarify content: Speak to your lecturers and tutors often to help you clarify the content and refine your understanding.

- Engage with university resources: Seek support from student bodies, libraries, and student support services to strengthen study habits and develop soft skills.

- Develop self-efficacy: Engage in activities that promote confidence, such as participating in class discussions and preparing for classes.

- Reflect on past successes: Revisit your positive experiences to build a mental record of your capabilities.

- Practice resilience: Focus on effort and persistence rather than immediate outcomes.

- Welcome challenges: Instead of avoiding challenges, see them as chances to grow.

- Use affirmations: Regularly remind yourself of your ability to overcome challenges.

- Develop a growth mindset: Recognise that your abilities and strengths are not fixed. They can grow with effort and reflection.

2.9 Chapter summary

In this chapter, we have:

- identified that independent learning involves taking control of one’s learning, including setting objectives, evaluating progress, and self-reflection. Remember, this is a pursuit, the perfect student is a myth.

- examined a variety of skills required to be an independent learner, such as research, analysis, writing, time management, communication, and conflict resolution.

- considered the various support offered through universities, including: lecturers, tutors, student bodies, libraries, and disability services that are all worth exploring.

- examined how asking questions helps to develop a deep understanding and active engagement in class content.

- considered the variety of different class types at university, including lectures, tutorials, workshops, labs, and placements, each with different expectations and methods of engagement.

- determined that self-efficacy is the belief in one’s abilities and can be developed through engagement, reflection, time management, and self-care.

- examined how a growth mindset fosters resilience and a willingness to embrace challenges, while a fixed mindset can hinder personal and academic growth.

2.10 Reflection questions

- How would you define independent learning in your own words?

- What are some strategies that you can develop to take better control of your learning?

- Identify the support you might need in completing your university studies. Given the variety of support systems at university, are there any that you have not accessed that could help you on your journey?

- What steps can you take to improve your self-efficacy in an academic context?

- Can you identify a situation where you exhibited a fixed mindset? How might you reframe this using a growth mindset?

References

Ayllón, S., Alsina, Á., & Colomer, J. (2019). Teachers’ involvement and students’ self-efficacy: Keys to achievement in higher education. PLOS ONE, 14(5), e0216865. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0216865

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioural change. Psychological Review, 84(2), 191-215. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.2.191

Dweck, C. (2014). Developing a growth mindset with Carol Dweck [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=hiiEeMN7vbQ

Ferrer, J., Ringer, A., Saville, K., A Parris, M., & Kashi, K. (2022). Students’ motivation and engagement in higher education: The importance of attitude to online learning. Higher Education, 83(2), 317-338. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-020-00657-5

Holec, H. (1981). Autonomy in language learning. Pergamon.

Levy, S., & Treacey, M. (2015). Student voices in transition (2nd ed.). Van Schaik.

Van Dinther, M., Dochy, F., & Segers, M. (2011). Factors affecting students’ self-efficacy in higher education. Educational Research Review, 6(2), 95-108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2010.10.003

Zajacova, A., Lynch, S. M., & Espenshade, T. J. (2005). Self-efficacy, stress, and academic success in college. Research in Higher Education, 46(6), 677-706. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-004-4139-z

Zhang, Z., & Sihes, A. J. B. (2023) A Framework for Enhancing English as a Foreign Language Teachers’ Teaching Self-efficacy. China Secondary Vocational Schools. https://doi.org/10.6007/IJARBSS/v13-i8/18086

I would love to hear your thoughts on this chapter, share your feedback.

- Interestingly, there is a movement towards calling soft skills ‘power skills’. The connotation of soft skills is that they are lesser or less important and using the term power skills is meant to rectify this. ↵