Chapter 1: Introduction to university

Liam Frost-Camilleri

Learning Objectives

- Understand the challenges and benefits of university attendance

- Identify your personal motivations for a university education

- Analyse strategies in managing yourself and your learning

- Navigate university expectations and responsibilities

1.1. Beginnings

Deciding to attend university is a significant step, especially if you are what we call, first-in-family, live in a remote area, have a disability, or feel marginalised due to financial challenges or other reasons. There are assessments to research and write, feedback to navigate, new friendships to forge, and a need to balance your life with your study, work, and home commitments. Not to mention the expectations of being at university. You need to show independence by taking charge of your university studies; muster your self-motivation; find your resilience; and be open to working with others, while figuring out how you learn best and manage your time. Feeling anxious about this transition is entirely normal (and even sometimes desirable) as you navigate this new experience. While some aspects may seem daunting, the benefits of a university education can be profoundly eye-opening, life-changing, and well worth the effort. It may also help you remember that regardless of your situation, many people have benefited from a university education despite their challenges.

While it is true that you will enjoy a stronger economic advantage and better health outcomes when you complete a degree, it is important to highlight how critical thinking and reflection, when taught well, can change your life. You are not just learning about the content you are studying; you are learning about yourself. You are not just learning how to do a job; you are learning how to be critical and perhaps change the face of the profession you are entering. It is therefore worth considering not only the motivations that you have for going to university, but what else a university education might offer you.

1.2 Why University?

The reasons why students want to attend university can vary. While some students attend for career prospects, personal and academic growth (Universities Australia, 2022), social and family expectations (Arkoudis et al., 2019) and the potential to receive financial support such as scholarships (Cherastidtham et al., 2018), one of the primary reasons people choose higher education is economic (Trounson, 2018). Students want a ‘good job’ that ‘pays well’ and, while it is true that having a university education means that you may enjoy more economic stability later in life, there are other considerations to keep in mind. Additionally, many students hold lifelong dreams of attending university to enter an occupation that they have an affinity with but often believe that they are incapable until they begin attending.

Universities usually map the benefits to completing a degree to a series of ‘graduate attributes’ that are linked to researched findings. These attributes typically fall under a few basic ideas such as career advantages, personal development, societal impact, cultural competence, integrity, and creating supportive and inclusive environments. The aspect we would like to focus on here tends to fall under personal development, specifically two important skills known as ‘critical thinking’ and ‘reflection’.

While these two skills are related, there are some subtle differences between critical thinking and reflection. Critical thinking involves analysing, examining and evaluating situations and texts, as well as scrutinising your beliefs. It is a challenging process that requires you to think deeply about the world you live in and who you would like to be within it. The process of thinking critically helps you to make judgements, clarify situations, and articulate your perspectives. This skill can keep burning questions alive in your mind, helping you feel motivated, and assist you in making difficult decisions in life. At university, critical thinking is used to help analyse information, problem solve, write, and research as well as interact with lecturers and classmates. Reflection, on the other hand, involves thinking deeply about past events or your identity and reasons behind it. It can be a very personal exercise and sometimes reveals more than you expected. People who reflect often face hard truths and spend a lot of time journaling about their thoughts and attitudes. In courses such as teaching or nursing, reflection is used to improve job performance, but it is also employed in other courses to encourage deep thinking about assessments and feedback received. Reflection is a metacognitive tool, a way to think about your own thinking.

1.3 Anxiety

You are probably feeling a mix of emotions at the moment. The excitement of starting something new and progressing down a path you have always wanted mixed with the fear and uncertainty of what this adventure might bring. These are important emotions that need to be acknowledged, and it is worth focusing on anxiety specifically. It is well documented that beginning university can cause a high level of anxiety (January et al., 2018), which is not at all surprising. Fear of the unknown or making a fool of yourself are valid feelings that deserve to be acknowledged, but it is important to remember that small levels of anxiety can also be beneficial.

Since COVID-19, our collective understanding of anxiety has shifted to viewing it as concerning. The research shows a negative correlation between anxiety and academic performance, indicating a need for interventions and support (Osborn et al., 2022). We spend a lot of time trying to avoid anxiety, which can make it worse. Having anxiety about attending university is not only normal, but somewhat desirable as it provides an opportunity to understand yourself and your needs. The important point to remember is to develop strategies to address your anxiety. Get to know the supports at your university early; most provide access to free counselling services, coaches, learning specialists, disability liaisons, and study aids as a part of your enrolment. You will also find some information on dealing with anxiety in a later chapter of this book. Surrounding yourself with supports to find out what does and does not work will not eliminate anxiety but can help you to develop strategies to successfully manage it. Lastly, as a quick note, the anxiety discussed in this book does not include anxiety disorders. If you feel you may have an anxiety disorder, the first step in addressing it would be to make an appointment with a General Practitioner to review your options.

1.4 Imposter syndrome

Imposter syndrome refers to the feeling that your success is undeserved or that you are somehow unworthy of being where you are. Many students can feel like imposters when they first start university, and some even after they have completed a PhD, the highest degree you can obtain in higher education. Research indicates that imposter syndrome can lead to ‘compassion fatigue’, a growing inability to remain compassionate to your own situation (Schmulian at al., 2020). This compassion fatigue is why, if you feel you are suffering from imposter syndrome, it is important to share your feelings. You will likely find that many of your peers (and even your lecturers) feel the same way and can share their experiences, helping you find strategies to cope. It might also be helpful to focus on the facts of the situation: you are enrolled in the course, making you a university student and you deserve to be there. Being compassionate toward yourself by accepting your failures, celebrating your successes and letting go of perfectionism are all great ways to move past the idea that you are not ‘good enough’ to attend university. But this process will take time and effort. Additionally, you may feel that you are a perfectionist. Perfectionism has become a common trait for those who are studying, but it is important to understand that perfectionism is external; it aims to control the way people view you and hide shame or a feeling that you are not ‘enough’. The strongest antidote to perfectionism is vulnerability through discussing how you feel about the situation. Perfectionism can also make hearing criticism very difficult. Criticism and feedback are discussed at length in Chapter 6 of this textbook. There you will learn that being able to navigate feedback that might be difficult to read or hear is an important skill to learn when studying. Moving away from perfectionism and towards healthy striving will change your perspective from what others think to your own personal growth, while making you more receptive to feedback.

Learning Activity 1.1 Understanding why you are attending university [PDF]

It is important that you examine your reasons for attending university and acknowledge your anxieties so you can start to move past them. Try responding to these questions to help you through the process:

- Take a few minutes to reflect and think about why you decided to attend university. List three potential reasons.

- Do these reasons relate to what was written in the Chapter? How are they the same and how do they differ?

- What are your two main anxieties about attending university?

- What are some ways that you can start to address these anxieties?

1.5 Transition

Over the years, universities have experienced what we call ‘increased participation’. Increased participation means that more people are enrolling into university than ever before, and those people are from different walks of life. While increased participation is positive because it means more people are gaining access to valuable education, it also presents universities with the challenge of catering for different students with diverse needs. Research indicates that universities are not always great at assessing and meeting student needs, even though they are trying to. The sticking point here tends to be differences between the expectations of students and the expectations of the university.

1.6 University Expectations

The expectations of university mainly revolve around attendance, participation, organisation, and conduct in class, which is why being an independent learner is so important. To meet many of these expectations there is a need for you to take control of your learning. There is more about independent learning in Chapter 2.

While university can resemble secondary school in terms of lecturers’ varied teaching styles, it differs greatly in that most lecturers will rely on university systems to actively monitor attendance, completion of work, or academic progress. Lecturers will collect data on these things, but will generally not spend time following these aspects up. If you receive a phone call or email from the university about your attendance or academic progress, it generally will not come from the lecturers (depending on the university). This hands-off approach may seem strict, but it does not imply a lack of support or care. While the lecturers may not regularly check on your progress, they are generally willing to assist if you reach out to them. Additionally, universities typically offer supports such as organised study groups, peer mentoring by graduates of your program, and access to counselling, financial, and medical services. However, it is your responsibility, as a student, to seek out these resources, making it crucial to be well-informed about what your university provides.

It is important to understand the role of your lecturers. Secondary school teachers focus on guiding students through structured curricula, and introducing foundational knowledge. In contrast, lecturers see themselves as subject specialists or researchers; merely a guide to the advanced content they present. Importantly, lecturers tend not to see themselves as teachers. This means that, unlike teachers, most lecturers and programs will not accept drafts of assessments; you typically have only one chance to submit your assessment. While some lecturers may provide feedback if your work does not meet their expectations, this is not always the case. Therefore, it is crucial to be clear on what is expected of you for every class and task. It is worth noting that in certain situations you will be offered additional opportunities to demonstrate your understanding through supplementary tasks or resubmissions. These tasks are given by university lecturers if they believe you need another chance to meet the required level of their course or unit.

Universities will always provide written details about their assessments, including deadlines, marking criteria, procedures for extensions, and the expected length and format of your submissions. This information is typically accessible through an online learning system or course booklet. It is crucial to record the assessment dates and consider how much time you will need for each task. Assessment deadlines are usually strict, and late submissions often incur penalties such as a loss of marks, impacting your overall grade. While some lecturers may remind you of upcoming deadlines, others may not, so staying organised and aware of deadlines are essential when becoming an independent learner.

1.7 Success

Many students are very focused on achieving success when they first attend university. The main challenge with success at university lies in the grading system. Most universities employ a grading system such as ‘High Distinction, Distinction, Credit, Pass, Fail’[1] where a score of 50% usually constitutes a passing grade. It is common for students to aim for High Distinctions in their first assessments. Achieving a High Distinction typically reflects an exceptional level of mastery, so it is important to manage your disappointment if you do not achieve it on your first few assessments. Failing an assessment similarly does not imply a lack of effort or not belonging to your course or unit. Often, a failed assessment can be compensated for by other assessments in the course or unit. For instance, if you receive a fail grade on one assessment (10/30 or 33%), but a pass on the next two (20/35 or 57% and 23/35 or 65%), your overall grade may still be a pass (10+20+23=53/100). Many students successfully navigate courses or units in this manner which may require you to adjust your definition of ‘success’.

Having clear expectations and goals to work towards is crucial for maintaining motivation and achieving success in your studies. For example, when starting a teaching degree, your initial goal might be to become a good teacher. However, as you refine your craft, your goal may evolve to: I would like to inspire others. Remaining open to adjusting your goals and redefining success is an essential aspect of personal growth during your university journey.

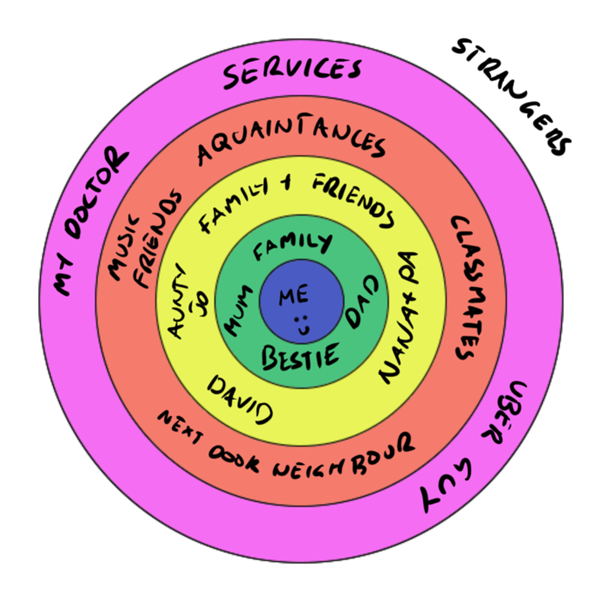

While your lecturers possess extensive knowledge of their content and research, your parents, siblings, relatives, or friends who have attended university may offer you advice. However, those who truly understand what you are going through are your peers in your class. While speaking to those around you can be helpful, it is important to remember that your fellow students are invaluable when navigating university life. Building friendships at university helps maintain engagement, a sense of belonging, and resilience during your studies. However, not all students navigate social dynamics smoothly. Having university friends does not necessitate becoming best friends or spending every moment together. Approach friendships at university with an open mind, understanding that they may only last for the semester or term and be limited to class interactions. This is often referred to as the circle of friendship, where university friends may fall into the ‘acquaintances’ circle (see figure 1).

While success at university can be influenced by various factors, one of the most significant influences is your own self-management. This book will cover resilience and maintaining focus, but fundamentally, you must learn to manage yourself. Becoming engaged in the course or unit materials, connecting with your classmates, attending class, asking questions, and starting your research early are all helpful ways that you can ensure your success at university. Remember why you started this learning journey and keep your goals in mind; they will guide you through this wonderful challenge.

1.8 Balance

While many university courses consist of classes that only meet for 2-3 hours a week, you will quickly discover that the amount of study involved is more substantial than anticipated. Due to this intense workload, it is crucial to discuss how you will strike a balance between home, work, and study life. Throughout this book, there are various strategies to enhance your engagement with university study, but it is important to acknowledge that balance can sometimes be elusive. We often talk about balance when we have not prioritised something important, such as spending time with your family or completing assessments on time. Striving for balance may not account for the intensive time needed for certain aspects of life. Assessments may require sacrificing other priorities, just as attending to a sick family member demands focused time and attention. Instead of searching for a balanced approach, managing situations effectively may involve focussing intensely on what is most critical at the time. Here are some strategies to help identify these priorities and navigate these challenges:

Engaging a flexible routine. It may seem counter-intuitive to the above points about balance being elusive, but engaging in a flexible routine can be highly beneficial. Establishing a weekly or daily flexible routine allows you to allocate time to your priorities while remaining adaptable to important tasks as they arise. For example, you might plan to study from 4:00 p.m. to 6:00 p.m. every day, followed by an hour of exercise just before dinner. If something urgent comes up, such as a group meeting or unexpected errands, you can shift your study time to earlier in the day while still maintaining your overall structure. Following a routine also provides a sense of familiarity and can contribute to improved mental health. However, when developing a flexible routine, it is crucial not to compromise on sleep. Adequate sleep is essential for effective learning, so ensure you prioritise sleep and, during busy times, aim to get more sleep than you normally would to aid recovery.

Setting boundaries. Many people find setting boundaries quite difficult, but it is crucial to maintain focus on your goals and achievements. Learning to say ‘no’ in favour of your own needs is essential for taking control of your educational journey, especially as assessment and exam times approach. It can be difficult to set boundaries when you are not used to it, consider using phrases like the following:

- “I’d love to help, but I need to focus on my university work right now.”

- “I’m sorry, I cannot commit at the moment as I have some deadlines to meet.”

- “I really appreciate the offer, but I need to prioritise university at the moment.”

It can also be helpful to set some clear expectations for those around you by letting your friends and family know the times you will be unavailable due to study.

Looking after yourself. Aside from getting enough sleep, it is vital to incorporate self-care practices into your study routine. Eating light nutritious meals, engaging in enjoyable exercise (even if it is simply a walk around the block), and setting aside time for reflection and debriefing are all key ways to effectively navigate your university experience.

Seeking support when you need it. As mentioned earlier, knowing when to seek support is crucial. A study that I am involved with has highlighted that neurodiverse students in particular often delay seeking help until it is too late. Recognise when you require assistance and seek it early to ensure you receive the support you need.

The “third place”. Having a third place is crucial to maintaining focus, preventing academic burnout, and staying connected. The third place is distinct from your home (first place) and work or study environment (second place). The third place can be a variety of different options, such as gyms, cafés, pubs, clubs, a band, a sporting club, a community group, and a book club. These spaces provide essential respite and connection outside of your usual routine. If you have not identified a third place yet, consider exploring different options to help regulate your emotions and enhance your connection to the broader community.

You can see from this first chapter, much of what is expected from you at university requires significant emotional and personal regulation, as well as an understanding of university expectations. Remember to be kind to yourself. You will not get everything perfectly right, and that is okay. Most learning happens through making mistakes.

Redefining what success means to you and finding ways to better balance your life are going to be important parts of managing yourself while you go through your university degree. Complete the following steps to reflect and take practical steps:

1. What does/will success mean to you?

- Write down your current definition of success in 2-3 sentences.

- Reflect on whether this definition is rigid or flexible. If it feels rigid, note down ways you could adjust it to make it more flexible.

For example, if your definition of success is achieving top marks in all your subjects, you might adjust it to focus on giving your best effort and maintaining a healthy balance between study and other aspects of life.

2. How might you pivot your understanding of success if you do not reach your goals?

- Think of a time when something did not go as planned (e.g., a goal you did not achieve). Reflect on how you felt and how you responded.

- Now consider how you could approach a future situation where you do not meet a goal. Write down two alternative ways you could redefine success in that scenario.

3. What would be your ‘third place’ and what does it offer you?

A “third place” is a space outside of home, university or work, where you can unwind and connect with others.

- If you already have a third place, reflect on what it offers you and how it helps you recharge.

- If you do not have one, explore at least one potential third place, such as a park, café, library, or gym. After visiting, reflect on how it made you feel and whether it could support your sense of balance.

1.9 Key strategies from this chapter

- Managing anxiety: Acknowledge that anxiety is a normal part of transitioning and use support systems and strategies to manage it.

- Address imposter syndrome: Combat imposter syndrome by sharing feelings with peers or lecturers, focusing on facts, being self-compassionate, and challenging perfectionism.

- Understanding university expectations: Be proactive in understanding university expectations regarding attendance and participation.

- Redefine success: Adjust your definition of success from purely academic achievement to include personal growth and resilience.

- Build a flexible routine: Establish a flexible routine that allows for balancing academic and personal commitments.

- Prioritise self-care: Incorporate regular self-care practices such as exercise, nutrition, and reflection into your routine to maintain well-being.

- Identify a ‘Third Place’: Find and engage with a ‘third place’ outside of home and university to unwind, recharge, and maintain emotional balance.

- Seek support: Recognise when you need support, and seek it early.

1.10 Chapter summary

In this chapter, we have:

- examined the difficulties students face when transitioning to university, particularly for those of marginalised groups.

- discussed how anxiety impacts studying and highlighted its potential benefits and strategies for management.

- considered the key expectations related to attendance, participation, organisation, and conduct at university.

- began discussing ways to manage yourself effectively while at university.

- considered strategies for achieving balance between study, work, and personal life, emphasising the importance of flexibility and self-care.

1.11 Reflection questions

- What are your primary motivations for attending university? How do they influence your approach to your studies?

- What specific challenges do you anticipate facing as you transition to university life? How might you prepare for these challenges?

- How does anxiety manifest for you in academic settings? What strategies have you found effective in managing it?

- What expectations do you have about university, and how do they align with the expectations outlined in this chapter?

- Reflect on your current self-management strategies. What works well for you, and what areas need improvement?

- Identify your ‘third place’ or a potential ‘third place.’ How can this space contribute to your overall well-being and success at university?

References

Arkoudis, S., Dollinger, M., Baik, C., & Patience, A. (2019). International students’ experience in Australian higher education: Can we do better? Higher Education, 77(5), 799-813. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-018-0302-x

Cherastidtham, I., Norton, A., & Mackey, W. (2018). University attrition: What helps and what hinders university completion? Grattan Institute. https://grattan.edu.au/wp-content/uploads/2018/04/University-attrition-background.pdf

January, J., Madhombiro, M., Chipamaunga, S., Ray, S., Chingono, A., & Abas, M. (2018). Prevalence of depression and anxiety among undergraduate university students in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review protocol. Systematic Reviews, 7(1), 57. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-018-0723-8

Osborn, T. G., Li, S., Saunders, R., & Fonagy, P. (2022). University students’ use of mental health services: A systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Mental Health Systems, 16(1), 57. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13033-022-00569-0

Schmulian, D., Redgen, W., & Fleming, J. (2020). Impostor syndrome and compassion fatigue among postgraduate allied health students: A pilot study. Focus on Health Professional Education, 21(3), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.11157/fohpe.v21i3.388

Trounson, A. (2018, August 13). Financial anxiety widespread among university students. Pursuit. https://pursuit.unimelb.edu.au/articles/financial-anxiety-widespread-among-university-students

Universities Australia. (2022). Higher education facts and figures. Universities Australia. https://universitiesaustralia.edu.au/publication/higher-education-facts-and-figures-2022/

I would love to hear your thoughts on this chapter, share your feedback.

- This grading is roughly equivalent to the ‘A, B, C and D’ system that you might have seen in secondary school. ↵